Daniel Taradash:

Triumph and Chaos

Interview by David Thomson

"Please tell Dan Taradash how much I liked it," wrote James Jones to the producer of From Here to Eternity (1953). "I don't see how in hell he could have managed all the rearrangements he has . . . and still come up with an interpretation that hits so close to the original intention of the book."

This was no polite praise. Jones had had an inglorious shot at adapting his own book first. Even Columbia's chief, Harry Cohn, was losing heart with a property so damning of the army and so riddled with "pornographic" language that maybe no one could bring it to the screen in a manner fit for Eisenhower's America.

Dan Taradash's visionary solutions—especially the handling of the Maggio character—seem so "right," it is hard to believe they are not in the original novel. Moreover, as this interview makes clear, Taradash was a leading supporter of Fred Zinnemann as director of the film, and a participant in the cunning casting program that had so much to do with the artistic success and the overcoming of audience distaste for the famously "dirty" book. After all, if Donna Reed and Deborah Kerr could do it, then surely the Midwest could see it.

From Here to Eternity remains a brilliant example of Hollywood's constructive compromise. It is not quite the book, yet it can have disappointed very few readers; it does not go easy on the army, but only because it soars on the romantic individualism of its lead characters. Montgomery Clift's Prewett may be the most appealing and least self-pitying rebel Hollywood has ever produced. The picture had a domestic film rental of over $12 million in 1953–1954; it won Best Picture, as well as Oscars for Sinatra, Reed, cameraman Burnett Guffey, Zinnemann, and screenwriter Daniel Taradash.

Who could have guessed then that nothing would ever again be quite as good for the writer? In hindsight, Taradash can be seen as a master of adaptation, and a quiet, gentle craftsman, always inclined to go home to Florida, who somehow got along with the abrasive, overbearing Harry Cohn. From Golden Boy (1939) to Bell, Book and Candle (1958), Taradash worked for Columbia on most of his projects, despairing of the boss frequently, yet feeling the hole left in the business when Cohn died. However rough he was to deal with, Cohn got good pictures made and he allowed Taradash his chance at directing, on Storm Center (1956).

The disappointments that began around 1960 have not dimmed Taradash's humor or goodwill. Still, the list of projects shelved or spoiled in the making is a chronicle of the disasters that befell independent production in the 1960s.

A great deal of Taradash's best time and effort were given to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and to the Writers Guild. A member of the guild since 1939, he has served on over thirty of its committees, often as chair, and he was president of the Writers Guild West from 1977 to 1979, as well as a trustee of its Pension Plan from 1960 to 1973.

As for the academy, he was a board member from 1964 to 1974 and president from 1970 to 1973. It was in that period that the building on Wilshire Boulevard was approved as a home for the excellent theater and the Margaret Herrick Library. In addition, Taradash is proud to have urged the giving of the Thalberg Award to Ingmar Bergman and to have led the campaign for a special "homecoming" award to Charlie Chaplin.

Not that he has given up screenwriting. In December 1987, when this interview was conducted at his home in Beverly Hills, Taradash was at work on a script about the life of Polish labor leader Lech Walesa, with old friend Stanley Kramer as director and television game-show producer Ralph Andrews as the "nut" who thought it could work. There had been a trip to Gdansk as far-fetched and turbulent as anything from the days with Cohn or Jed Harris. The Walesa project seemed less viable than many other scripts Taradash had believed in. But in the film climate of the late 1980s, that was no reason for thinking it wouldn't get made.

Daniel Taradash (1913–)

1939

Golden Boy (Rouben Mamoulian). Co-script.

For Love or Money (Albert S. Rogell). Co-screen story.

1940

A Little Bit of Heaven (Andrew Marton). Co-script.

1948

The Noose Hangs High (Charles Barton). Remake of For Love or Money .

1949

Knock on Any Door (Nicholas Ray). Co-script.

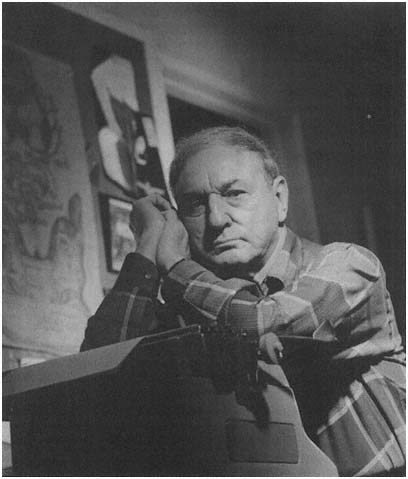

Daniel Taradash in Los Angeles, 1988. (Photo: Alison Morley)

1952

Rancho Notorious (Fritz Lang). Script.

Don't Bother to Knock (Roy Baker). Script.

1953

From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann). Script.

1954

Désirée (Henry Koster). Script.

1956

Storm Center (Daniel Taradash). Director, co-script, co-screen story.

Picnic (Joshua Logan). Script.

1958

Bell, Book and Candle (Richard Quine). Script.

1965

Morituri [a.k.a. The Saboteur: Code Name Morituri ] (Bernhard Wicki). Script.

1966

Hawaii (George Roy Hill). Co-script.

Alvarez Kelly (Edward Dmytryk). Uncredited contribution.

1969

Castle Keep (Sydney Pollack). Co-script.

1971

Doctors' Wives (George Schaefer). Script.

1977

The Other Side of Midnight (Charles Jarrott). Co-script.

Plays include Red Gloves (adapted from the Sartre play) and There Was a Little Girl .

Television credits include "Bogie" (1980 teleplay). Academy Awards include Best Screenplay for From Here to Eternity .

Writers Guild awards include a best-script nomination for Picnic and the award for the best-written drama of 1953 for From Here to Eternity .

When I look at the facts of your life, it looks like someone who was heading for one career, the law, but there was something else under the surface .

Well, that's not altogether true. I was an only child, and my father was extremely anxious for me to be a lawyer. I didn't really know what I wanted—I just had a feeling I wanted to be a writer, because I had done some writing at Harvard and received favorable indications from some of the professors that there was possibly something there. But because my father wanted me to, I went to Harvard Law School—I think I had the largest number of cut classes in the history of the law school. And eventually I passed the New York bar exam. But while I was in law school I wrote a play which I sent to an agent in New York, and she indicated that it wouldn't work on Broadway, but there was something there.

I looked at my father and I said, "You've supported me seven years. And I want you to give me enough money to live on one more year. I want to try to be a writer." And then he looked at me and said, "Well, I think you're a damn fool. If you would ask me for five years, I'd take that seriously and respect it. But the notion you can spend one year in New York and you're going to be a writer is damn foolishness."

But he did it, because, he said, "I don't want you in ten years to say to me, if you'd only given me that one year I would have been so forth and so forth."

Except I fooled him. I wrote a play that year and entered it in a nationwide contest, and the money for the contest was put up by the motion picture companies, which were fairly intelligent in those days about reaching out

and finding people. There were three fellowships as prizes, and I won one and Helene Hanff won one![*] There was a playwriting course we took, and out of that—it was a great lucky break—came the first job in Hollywood.

We're talking about Golden Boy?

[Director] Rouben Mamoulian was going to do Golden Boy for Columbia, and they gave him a script which they had had prepared by two older writers. He threw it in the wastebasket and said, "I can't use this. We'll go to New York and try to get Clifford Odets." But Odets was apparently pursuing Luise Rainer, and she was in Paris. So somebody said to Mamoulian, Why don't you take a look at stuff the people at the playwriting course are doing? He did, and he liked two of us—Lewis Meltzer and me.[**] He called us together and said, "I'll have Columbia employ you both for a couple of weeks. Go away and each write me a script for the first twenty minutes of the film." I wrote in one part of town and Meltzer in another, and we gave Mamoulian the material. He said, "I simply can't decide between you. I'll take you both!" He told Harry Cohn he was going to take two $200-a-week writers. Cohn screamed at him and said, "For Christ's sake, forget that nonsense and get yourself a $5,000 writer." Well, Mamoulian wasn't that type, and it worked out.

Did you work as a team then?

Oh yes. Mamoulian never wrote anything, but he talked about it all the time as we went along. He was so intelligent, and he had a very private, very charming sense of humor. Harry Cohn was driving him crazy. I remember meetings with Cohn where I was writing down notes from Cohn—"Make it more Capranese!" Stuff like that. Mamoulian was fed up with it. "Look, Harry," he said, "you're driving me nuts. I know a guest ranch in the desert near Victorville. Let me take those two boys out there and we'll bring you back a script in eight weeks." One of the most delightful experiences I ever had was working with Mamoulian and Meltzer in the desert.

Was it chance that there is a resemblance between the young man's situation in Golden Boy and what you'd been through in the law and writing?

To be honest with you, it never occurred to me. I don't think that much creative work was involved. It was a structural job and a dialogue job. We stuck pretty close to the play.

Did you foresee, then, that movies would be your career?

I wanted to be a playwright. When we finished Golden Boy, Meltzer stayed in California, but I went back to New York to finish my play, and Columbia

* Helene Hanff is known principally as the author of many dramatic television programs of the 1950s, as well as children's books, other books, and magazine articles. Her twenty-year transatlantic correspondence with the owner of an antiquarian bookshop in London became the source of a play and of the film 84 Charing Cross Road (1981).

** Apart from Golden Boy, Lewis Meltzer's long list of scripting credits includes The Tuttles of Tahiti (1942), Along the Great Divide (1951), The Man with the Golden Arm (1955), and High School Confidential (1958).

was very angry with me. So they punished me: when I came back they put me in the Katzman [producer Sam Katzman] unit, the B pictures. I did a script there based on Warden Lawes of Sing Sing—it was never made—and at the end of that they dropped my option.

Almost immediately after that I had a strange job with Joe Pasternak at Universal. They were grooming a girl named Gloria Jean to be the next Deanna Durbin, and it was a picture called A Little Bit of Heaven [1940]. I was one of three or four writers who worked consecutively on it.

Then there's an interval in your screen work which is the war?

I went back East because my mother was dying, and I just stayed with her and my father in Florida, and I wrote another play which I sold to a Broadway producer. I had a very low draft number. I would have been in the army earlier, but my draft board let me remain in Florida until my mother died. That was the end of February 1941, and in May I was in the army. But I was over twenty-eight, and there was a rule that civilians drafted over twenty-eight were discharged. With the proviso that if something important happened, you would be jerked right back in—and something important happened, so the play never got done.

The army was a big shock. I had been a Boy Scout, but not a very good one. My mother's death was somewhat traumatic, and then joining the army right afterwards in a whole different world was very good for me. But I didn't think it was good at the time.

I went to Officers' Candidate School after a while, and I hoped it would send me to the Signal Corps Photographic Unit, which was making the films for the army. It did, except they sent me first to the Army War College in Washington, where I helped write a Fighting Men series called Kill or Be Killed . Ed North was the other writer on the series.[*] Then they sent me to Long Island City and I worked on training films. One of them, Lifeline, was shown everywhere by the Red Cross to get blood donors. I was working with "film" there, which a writer would normally never get near in Hollywood.

How did you get back into the business?

A good friend of mine at college was [producer] Julian Blaustein and he was at the Signal Corps Photographic Unit—he made the famous film with Harold Russell which really led to Russell's getting the job with Willy Wyler on The Best Years of Our Lives [1946].[**] Well, he went to work after the war

* Edmund H. North, who also served with the Army Signal Corps, wrote for the screen from the mid-1930s and was responsible, alone or with co-writers, for several outstanding scripts, including Colorado Territory (1949), In a Lonely Place (1950), The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), The Proud Ones (1956), and Cowboy (1958). North collaborated on the Oscar-winning script for Patton in 1970.

** Harold Russell was a World War II paratrooper who lost both hands in a grenade explosion. The army documentary The Diary of a Sergeant, which depicted the rehabilitation of an amputee, led to his role in William Wyler's 1946 film about civilian life after World War II and to an Oscar as Best Supporting Actor.

with [David O.] Selznick as a story editor. Allan Scott was producing for Selznick, and Julie told him I would be good on an idea he had.[*] It was a thing called "Intimate Notes"—I read it again just last night and I was pleased—but Selznick didn't make any movies that year.

Did you still have attachments or obligations at Columbia?

I did know a story editor there, Eve Ettinger. That's how I got the job on the movie Bob Lord produced—Knock on Any Door [1949]. Eve called and said, "Why don't you come in. I think Bob Lord needs you." John Monks had written a draft, and they weren't happy with it. I knew Bob slightly from the army. He was a pleasant man and he did know what he wanted. Since he had also been a writer, there was the temptation of picking up the pencil and making changes. It wasn't good writing in my opinion. But he was an oddball. He was doing yoga when nobody had heard of it! I had a very good time with Bob on the picture, and Bogart was very pleasant. I think Nick Ray was strange and remote—I never got to know him in a personal way. He did a good workmanlike job, and he got as much out of John Derek as anybody could.

By that time were you living in Hollywood?

Not really. My wife and I had an apartment in New York, and my father had the house in Florida. I was a legal resident of Florida until 1977. We would drive from Florida to California in the spring every year, with a dog usually—we were breeding Dalmatians and showing them. I never could accept that I was living permanently in California. I guess if I had believed I was in Hollywood, then I would have given up this dream of the theater.

And it was at this time, 1948, that you had your Broadway experience with Red Gloves and [producer] Jed Harris?

It ran over 100 performances, but by the time the play opened I was—disenchanted is not the word—I loathed Jed Harris. He was a terrible sadist. He would humiliate you in front of the whole cast at rehearsals. The thing that disappointed me most was I never saw his "genius." He'd walked over to me one night in Murphy's, a prime-rib place, and said, "My name is Jed Harris." And he asked me would I do this play. I fell in love with him—I don't mean physically, but I revered him. I'd seen the plays, I'd even liked The Lake with Katharine Hepburn. Anyway, it wound up with my being physically afraid of the man! At one point he was screaming, about one o'clock in the morning. We were infuriated with each other about something in the play. He picked up a glass—I think it was a cognac glass—and I swear to God he was going to throw it right in my face. I tried to calm him down: "Come on, Jed—maybe you're right."

I've often said Jed Harris had two ambitions: to be a Gentile and to be a writer. But he could be one of the most charming men I'd ever met. I recall

* Allan Scott is interviewed in Volume 1 of Backstory .

sitting in a bar with him late at night, and he put his arm round me and told me wonderful things. I don't even remember what they were, but they were calculated to make me feel awfully good. Then he said, "Now, Dan, you know I've done a lot of work on this, don't you?" And then it led up to the fact he wanted my royalties! My God, I really believed him for a while. He was evil, enjoyed hurting people. He hurt [producer] Jean Dalrymple all the time. I don't know how the hell she took it—I guess she was in love with him. Red Gloves was a nightmare. Charles Boyer was the only ray of hope and light because he was a wonderful actor.

Rancho Notorious [1952] comes next. Did that always seem like a parody of a Western?

Well, it was. An agent named Milton Pickman called and said, "I can get you a job with Fritz Lang if you're interested, but I want to be the agent." Now I was doing something else, an anti-McCarthy picture for Stanley Kramer [which became Storm Center ], so I said, "I'll ask for something outrageous and they won't give it to me: $1,500 a week." They agreed!

Another thing was I met Lang. I read the story which had been written by Sylvia Richards,[*] but Lang had a great influence on it. He was a devotee of the American West, with a wonderful library. I said, "Mr. Lang, the only way I can see to do it is to put in something special. But instead of a narrator, I think we should use a ballad and jingles." This threw him for a loop, but it didn't change the picture much. Couple of days later, he said, "All right, let's do it." I learned more about screenwriting from Fritz Lang than from anyone. We would sit at his house over his dreadful coffee (the worst I've ever tasted) and we'd go over the stuff I was writing. I was showing him pages—that was mandatory. And he was literally working in every angle, over-the-shoulder shots, stuff like that. I learned how to choreograph a script. I said, "Why are you doing it this way?" He said, "I'll tell you, Dan. I love this story and what you're doing. But I am close to falling out with these guys"—our producers—" and it would not surprise me if at some point I am off the picture. I want a script that even an idiot can shoot."

But Fritz finished the picture, and he told me he had turned it in at an hour and forty-five. A few weeks later I ran into Howard Welsch, one of the producers, and asked how did he like it. "Oh, fine," he said. "I cut fifteen minutes out of it." Now I knew it had been a tight cut for Fritz, so I said, "What did you cut?" And, so help me God, Welsch said, "I cut the mood!"

I think on From Here to Eternity your own great success was in "solving" how to do the book .

Well, the only person I know of who had worked on it was Jim Jones

* Sylvia Richards's other script credits include another Fritz Lang film, The Secret Beyond the Door (1948), as well as Possessed (1946), Tomahawk (1951), and Ruby Gentry (1952).

himself. He wrote a treatment, and he ruined his book. He was worried about censorship—everyone was—and in his treatment, the captain's wife (the Deborah Kerr role) is his sister! No movie. And the captain didn't apply the "treatment" to Prewett. He was a nice fellow and when he found out about it, he got furious.

I read the novel and thought, How the hell are you going to make a movie? And my wife and I were driving and I just sort of saw this movie. I went to Eve Ettinger and said I thought I could lick it. She got me in to see Buddy Adler, I told him a couple of ideas, and he flipped. In no time I was in Harry Cohn's bedroom. This was where he liked to have his meetings.

I said, "I'll give you two ideas. The first one is, instead of Maggio just petering out and being discharged and sent back to Brooklyn Maggio should be just the way he is [eventually portrayed] in the film." And the moment in the book when Prew played "Taps" had no reason. I said, "It's when Maggio dies! You've got a great second-act curtain." And I said you should intercut the two love stories, but they should never meet. The audience will get the impression that somehow they are related.

So Cohn said, "Negotiate with Briskin [staff executive Irving Briskin]." I asked for 2 1/2 percent profit participation—which was really the first time a writer had had that. I believe they went with it because they never thought it would happen! We're never going to get anywhere with this movie, so give him whatever he wants! Cohn, I think, had got discouraged about it. He paid $85,000 for the book, and he wondered if he had made a mistake, because the New York office was laughing at him. They thought, with all the "fucks" all over the book, you can't do it. They didn't stop to think you don't need that word. So I said to Harry, "Do you mind if I do some of this at home?" I think I meant Florida. He said, "As far as I'm concerned, with this book you can write it in a whorehouse!"

And the screenplay you did was very close to the final movie?

Very much. There were innumerable conferences with Harry Cohn, and with Fred Zinnemann after he got on the project. Cohn always liked to talk primarily to the writers, and his whole method was to irritate you, ask the same thing over and over until he drove you to the wall. When he saw you were about to attack him physically, he said all right, go ahead, do it, because he knew you really believed in it. But that can drive you crazy after six months. At one point I walked out because I thought I was going to vomit. [Producer] Buddy Adler calmed me down. He had a soothing influence, and he helped Freddie by being a buffer.

I had seen Teresa: I thought Zinnemann had done a marvelous job with the GIs in that picture. I said to Adler, take a look, and he was very impressed. And we said, Let's see if we can talk Harry into this. Zinnemann was then shooting a picture up in Stockton, Member of the Wedding [1952],

and word was coming down that he was being very difficult. Cohn said, "Look, I can't do it, Dan. I got too much at stake on this picture to take any chance with a guy who may be trouble."

By then Zinnemann had seen the script, and we had a very good relationship from the word go. I said, "All right, Harry, it's your studio. But one day I'm going to work with Zinnemann." I think that impressed Cohn. He said, "I'll tell you what. Zinnemann is finishing next week in Stockton. I'm going to have him in my office, and I'm going to have the other fellow who's been feeding me the information about the trouble. At the same time. Is that fair?" And that's the last we ever heard of Zinnemann not doing the picture.

Were you part of the casting process?

Yes. Zinnemann said he couldn't do it without Monty Clift. Cohn said, "No. I've got Aldo Ray here. He's going to be a big star. Let me make a star out of this picture. This is my studio, and the people in New York have a right to expect something." Freddie said, "I know Aldo Ray. He will be a big star"—nobody believed that—"but this isn't the right picture for him." But Zinnemann said he would test him. And they did the scene in the New Congress Club. They had to get an actress to play with Ray, and they sent over a girl under contract at Columbia. It was Donna Reed. She wasn't in there to be considered, but just to read back the lines. Zinnemann didn't do a typical test; he did a scene, with angles on her and on Ray. I think Freddie was, in a way, testing the scene. Nobody ever heard of Aldo Ray as Prewett again, but Reed got the part of Lorene, the prostitute. And Clift got Prew.

Cohn could see things like that?

He had instinct. There were aspects of Harry Cohn which made certain people like him very much. A lot of people just despised him. And I know that he could be brutal, particularly to little people and in having people watched and followed and tapped. But there was a moviemaker there.

Donna Reed was not chosen immediately. Roberta Haines was testing, but I began to like the idea of Reed because she had given the part something I had never thought of.

Lancaster was almost a given from the word go. Joan Crawford was mentioned for the wife, and Cohn kind of liked the idea. Zinnemann had a long conversation with her, and he said, "I think she can do it, and she says she'll play it without the frills and the glamor." She was more or less cast until one day they got a call saying she wanted her own cameraman and makeup. Cohn and Zinnemann shook their heads, and that was the end of Joan Crawford.

So there was nobody. Well, I was driving back to Miami, and I stopped in Tucson to call the studio, and they told me, "Bert Allenberg has come up with a notion that we all like, which is Deborah Kerr." I said, "My God, that's as crazy as Donna Reed."

Now Sinatra did campaign for the part. He came back from Africa, where Ava Gardner was shooting Mogambo [1953], to test. He did the scene where

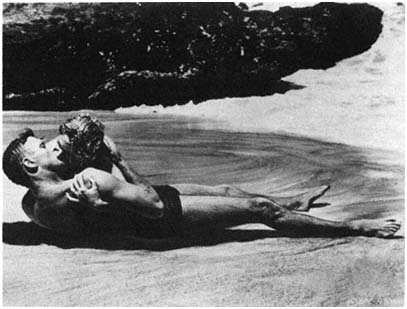

Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr in the famous love-on-the-beach scene in the film

version of James Jones' novel From Here to Eternity, script by Daniel Taradash,

directed by Fred Zinnemann. (Photo: Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

he throws off most of his clothes and says, "Can't a man get drunk?" He came up to my office and said, "How do I play this part?" I said, "You make them laugh and cry at the same time." And it was a good test. But they were testing Eli Wallach in the same scene and he was better—no doubt about it. But then Wallach's agent asked double the amount Wallach made on his last picture; otherwise he was going to do Camino Real on stage with Kazan. Cohn said, "Tell him to go to hell." This was the kind of thing you couldn't pull with Cohn, and an agent should have been smarter than that.

So we took another look at the Sinatra test. And there was one part about it that was better than Wallach's. Stripped to the waist, Wallach looked as if he could take care of himself. But this poor little Sinatra looked like a plucked chicken! You know, he was pitiful. Just what you wanted. And we looked at each other and said, let's go with it.

Were you on the Eternity set much?

A few times. It was a happy experience, and Geoffrey Shurlock at the Breen office was leaning over backward to help us. One thing that bothered them: In the fight where Lancaster confronts Borgnine, Lancaster picks up a bottle of beer and smashes it. That was in the script. They said don't do it, because there are countries where they won't run that. So we said, all right,

if it's that important. Just hold the bottle, as though he's going to hit him over the head with it. Well, I came on the set as they were shooting that moment. I'm standing with Adler and the camera's running and I see Lancaster pick up the bottle and smash it on the table. I say, "For Christ's sake! We said we wouldn't do that!" And Fred says, "Oh, fuck it!" That was the attitude—we were going to make this movie our way.

But I lost one line I loved. After Maggio dies, Lancaster picks him up and walks back to the jeep and puts his body down, and the guy starts the jeep. And Clift was to say to the driver, "See his head don't bump." But Clift read it so badly, they didn't use it. Zinnemann told me they didn't use it because Cohn didn't like it, but I don't think so.

Clift was terrific, and worked like a dog. He took it all so seriously, learning to march, to bugle, to box—things he had never done before. He was awful at boxing, and there's a double in some of those scenes. There's one scene, after he's stabbed and comes to the bungalow where the girls are, and he has to fall down [some] stairs. I watched that actor do it and I said, "My God, he's going to kill himself!" I think it was one take. He could've fractured God knows what!

When did the picture open?

August '53. Broke every record for twenty weeks. And it's the first movie where the screenwriter stole the reviews. Because it was still felt that the book was impossible to film.

Désirée [1954] was a big change of pace .

Julie Blaustein and I wanted to make a different picture, based on the idea that Napoleon should not be the leading man. We thought Bernadotte was a more intriguing subject—a man who renounces his country to become the monarch of another country and then comes back to wage war against his former country and marries a French woman who had been Napoleon's mistress.[*] Zanuck read that treatment and said no way. I guess it's because he was a little man and he was Napoleon over at Fox. He said you can't have Napoleon as number two in a motion picture. So we did it his way, but I wrote it with the idea of Noel Coward as director. We got Henry Koster instead. And Brando just walked through most of that picture like a moose. But it was kind of a silly story.

Picnic [1956] seems like a much happier job, and a fine adaptation .

There was much transposition. Also, there's no picnic in the play; it all takes place in the backyard. You've got to have a picnic in the film, and the

* Jean Baptiste Jules Bernadotte (1763–1844), a French soldier who took part in the French Revolution, served in the diplomatic service for Napoleon (1798–99) and rose from the ranks to become one of Napoleon's marshals. In 1810, Charles XIII of Sweden, aging and childless, adopted Bernadotte, who was then elected crown prince and took the name Charles John. In 1813 he allied Sweden with England and Russia against Napoleon and aided in defeating him at Leipzig. He succeeded Charles XIII in 1818, and, as King Charles XIV John, founded the present Swedish royal line.

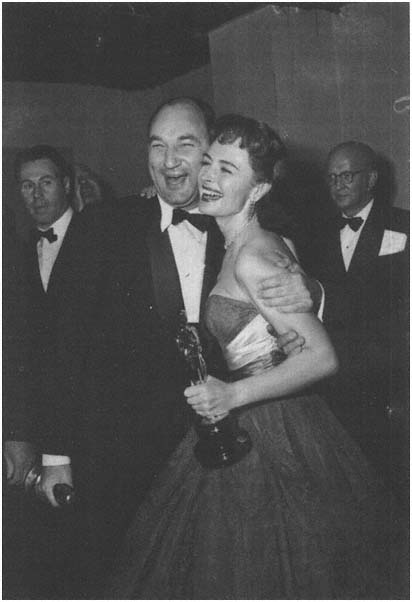

At the Oscars: adaptor Daniel Taradash and Best Supporting Actress Donna Reed,

clutching their statuettes for From Here to Eternity at the 1954 Academy Awards.

(Photo: UCLA Special Collections)

picnic I wrote is one you see . [Director Joshua] Logan was such an enthusiast about it.

He had also done the stage play?

And he had persuaded [playwright] William Inge to make it a happy ending. Inge was always disappointed about that—even after the Pulitzer Prize. I went to see him before starting to write and he said, "Look, it's yours now." I said, "But isn't there anything you want me particularly to hang on to, that you'd feel awful if you lost it?" He said, "No. DO it your way." He was not rude, but he seemed uninterested, and may be it's because there was going to be a happy ending in the movie, too. But Logan did a fine job staging it.

At one point, I was supposed to direct it. I gave it up because I wanted to do Storm Center [1956]. Anyway, I would never have gotten the picture Logan got out it. And Cohn was happy I didn't direct it, because he didn't like the way I directed Storm Center .

Had the wish to direct been growing slowly?

From about '52. From Here to Eternity had lifted me into a position where you could think about it seriously. It wasn't because my scripts were being ruined. They were being directed very well.

So how did Storm Center work out?

Well, Elick Moll and I did script for Kramer. And then there were many more drafts over the years. Once Ingo Preminger told me he thought the drafts got worse. I believe we refine pictures too much sometimes. I have a feeling that my first draft is my best shot and I'm not really as good on revisions and polishes. And I think it was that first draft Mary Pickford committed on.

Irving Reis was supposed to direct it then. I thought of Mary Pickford [for the part of the librarian]. This was a terribly difficult picture to make because it ran counter to the entire mood in the country, with the Unfriendly Ten [ *] and a picture where we defend a book called The Communist Dream being in a library. Nobody could accuse Mary Pickford of being un-American. And I had read that she would like to do another film. Stanley got in touch with her and we went up to Pickfair. I read the entire script to her and she was wild about it. I think she was crazy about the gigantic part. It ran the gamut, and she had great scenes to play with a little boy. I don't know whether she realized what the score was when it came to politics. I remember we walked out of Pickfair, and Stanley threw his arms round me and we were in seventh

* The Hollywood Ten were called "unfriendly" because they chose not to cooperate with the HUAC hearings of October 1947. The first ten film-industry figures to be subopened by the HUAC were writers John Howard Lawson, Alvah Bessie, Dalton Trumbo, Lester Cole, Ring Lardner, Jr., Sam Ornitz, and Albert Maltz, producers Adrian Scott and Herbert Biberman, and director Edward Dmytryk. All served time in prison for refusing to testify about their supposed affiliation with the Hollywood section of the Communist Party. Dmytryk, after his stint in prison, backpedaled and gave widely publicized testimony "naming names."

heaven. She came to the studio for fittings and then she backed out—Hedda Hopper got to her. Still, we'd had a New York Times story on her return in which she'd said, "It's about the most important thing in America today!"

So Columbia said forget it. Stanley went after Barbara Stanwyck and she liked it, but that fell apart. Then Kramer finished up at Columbia and left two or three of his things in exchange for a property. That's how Columbia came to own it. But they never wanted to make it.

Well, we said, we'll get Bette Davis. She was very excited about it. She agreed to take less than her normal deal. I'll never forget when Cohn finally agreed to it. I launched a campaign with him. We would go up and tell him it was a big commercial picture. He didn't believe it. And we didn't—Blaustein and I. We said, we'll get every schoolteacher in America and every librarian. We're really giving it to him. Ben Kahane [Benjamin B. Kahane, longtime Columbia vice president and one-time president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences] was in Cohn's office the day Cohn finally said, "Okay, go ahead and make your goddam picture—$800,000, and not a penny more." Kahane says, "Harry, you can't do this. This is an absolute flop, and you know that!" And Cohn says, "Ben, Columbia's had flops before. But we've never had a flop with such enthusiasm!"

How did you enjoy directing when it came to it?

I enjoyed Bette Davis. We got along very well in our preproduction talks. The cast was to meet at nine o'clock on the first day of rehearsals. On my way there I got held up in the production office, five minutes, eight minutes. Anyway, we [were supposed to] read the script, except that Bette didn't read it. She knew it, word for word. She was a wonderful thing to watch. When we'd finished, she took me aside and she said, "Look, when you ask me to be on the set at nine, I will be there and you will be there. I will not stand for anyone coming late."

But we got along well. We were shooting up in Santa Rosa and she finally got a day off. We had to shoot with some little boys on a residential street. We made the tracks and we had these boys going past a house when some shrew starts screaming from the house: "Get away from there! Don't you dare shoot your pictures here." I turned to the assistant director and said, "What is this?" He said, "They got the money, for God's sake!" So I walk in to see the "shrew"—and it's Bette! That's the way she used her day off.

But I must say something the Writers Guild won't like. I always used to think the writer was the loneliest guy in the world. But when I was directing—and I had good help—I felt the director was the only person thinking about the movie. I guess Julie was, too, the producer. I never realized the possibility of directing. I was more caught up with the glamor of talking to the actors. It was interesting, but it was frustrating.

I had spoken to Wyler and Kazan and asked, "Tell me in a sentence—

what should I do?" Gadge [Kazan] said, "Do everything your own way." And Wyler said, "Resist the temptation to be a good fellow." Unfortunately, I did neither.

How was the picture received?

The reviews were not good. The McCarthyites didn't have to kick it. Nobody was coming to the theaters anyway. It really had "message picture" all over it. The only way you can do a message picture is obliquely.

Bell, Book and Candle [1958] I think, you bought from Selznick; and his ex-wife, Irene, had produced it on stage .[*]

We had a problem getting Cohn to buy it. Selznick wanted $100,000, which was modest, I thought. Cohn kept saying it's a fantasy and we can't do fantasy to make money. I said, "Fine, Harry, but how did Here Comes Mr. Jordan make money?" He said it made $800,000, and it would have been $8 million if it hadn't been a fantasy.

We were going for Cary Grant and Grace Kelly, and we tried to get Alexander Mackendrick to direct. Mackendrick wanted changes we didn't want to make. Grant the same. Then Kelly got married. So we were hoping for Rex Harrison then, and Cohn kept saying, "You know, [Kim] Novak has got to play it." But he couldn't give us Novak for ten months and Harrison wouldn't wait.

Cohn forced Kim Novak on people?

I think he forced her on Logan for Picnic . She came to me one day, almost crying, and said he was teaching her how to walk down a staircase. I said, "Tell him you're afraid and sometimes you get nervous." She said, "I can't do that—he'll throw me down the staircase." But I thought she came out well in Picnic . On Bell, Book and Candle, the first couple of weeks she was playing as if she were a witch. There was none of that old-world chemistry between her and Jimmy [Stewart] on screen.

This is 1958, I think, the year Harry Cohn died. How much of a milestone was that?

Cohn in a way was lucky he died when he did. Because he would never have been able to cope with the type of independent production that began. On Bell, Book and Candle, for example, we gave him the script and he said, "I'm not going to tell you what I think of this. Because you can turn me down. Unless I get the last word, I don't want to get involved." It was bothering him terribly. There's another picture which I didn't get made—Andersonville, the MacKinlay Kantor novel, which Cohn bought against the wishes of his New York people, I was writing the script when Cohn died, and i think it could have been a remarkable movie. But it's interesting [that] you say an

* Bell, Book and Candle, from the John Van Druten play, stars Jimmy Stewart as a publisher under the seductive spell of a witch played by Kim Novak. The 1958 film version was directed by Richard Quine.

era sort of died with Cohn and people like Cohn. Because my credits after that are not very good.

Hawaii [1966] must have proved a great disappointment .

It was. It took up a solid year, '60–'61, and I was very depressed after I left the picture. It was my proposal to Freddie Zinnemann that we do two pictures and sell tickets as a pair—there's no way of doing that whole book even in three hours.

United Artists liked the idea and so did [producer] Harold Mirisch. We had a big meeting planned in this house. Freddie and I were here and Harold was late. He had had a heart attack and he died a year or so later. It was a bad omen. And I overresearched the picture. I had written forty pages of screenplay, and I felt I just couldn't do the two pictures in time. I suggested getting Dalton Trumbo in. But they read the forty pages and they were crazy about it. They said they'd wait. The two films were budgeted at about $17 million. Well, I got 180 pages of script and I had lunch with Freddie and told him, "Do just the one film and call it a day. I don't know whether any one director would have the stamina to cover this entire thing." He wanted to go all the way, though, and that's when I left. They brought Trumbo in and then [director] George Roy Hill. Freddie could never get the money for two pictures.

Morituri [1965] is another sad story?

Fox was in chaos. This was '62. Zanuck was living in Paris with Bella Darvi. The studio had this German novel, Morituri . I did the script on the third floor of that long, long administration building. I swear rabbits were running around! There was no business. No cars parked. A deserted village! Then Dick Zanuck came in. Then Darryl came back from Paris, and we had wild meetings with him in New York. He wasn't drunk, but he wasn't making much sense. He was furious about the room being overheated, but he didn't know to fix the gadget that turns it down. He did the same kind of things on the script!

It was absurd. I couldn't write like that, and the producer, Aaron Rosenberg, said even if I could, he wouldn't want to produce the film. Two years pass and Aaron meets Brando on Mutiny on the Bounty . They talk. One day my phone rings and it's Akim Tamiroff. No doubt about it—except that it's Brando doing the most marvelous imitation. And he was raving about Morituri, about what he thought it was! By God, we'll do this! On and on. And I signed.

We talked many times at Brando's place up on Mulholland, and he had a giant Newfoundland up there. He'd come in at eleven, hung over, sexed over, and God knows what. Then he wanted Bernhard Wicki to direct it. Wicki is a darling man, probably a good director in German. But he only spoke enough English to have dinner with. Brando changed enormous quantities, cut things, added. Wally Cox was in there, not credited, monkeying around.

Brando would come to a story conference and curl up in a chair in the corner in a fetal position. He was the Method actor carried to the wildest extreme. And he had complete control! He would like a scene one day. Next day he would say, "I can't do this. Let's do it this way." I would say, "You 're not doing this. It's the character."

Then my wife and I went to Egypt on a trip. When I got back a month or so later, I guess it was almost in the can. Aaron said to me, "It's just terrible, the things that have been going on. Brando barring the director from the set, then walking in at 5 P.M. and going to a dressing room, coming out at 6:30 and handing the scene to Wicki and saying, 'This is the way we're going to shoot it.' "

One scene was impossible. Rosenberg told me: "You've got to look at this scene and do something with it. We can't let the picture go out this way." It was a scene with Brando and the girl in the cabin and there was a porthole, but the porthole was covered over because this was a ship that was not supposed to be at sea. I'm watching the scene in the projection room and Brando walks over to the porthole and looks out. Aaron says, "What in the hell is he doing that for?" Well, he went over there because the blackboard was right outside and he was trying to read his lines!

I shouldn't have done the picture. I don't know—I thought it could make a good adventure story.

I believe you feel that, of the later films, Castle Keep [1969] could have been the best?[ *]

I knew what it was about: self-respect. Before the book was published there were reviews in Life and Time raving about it. It was so adaptable, I begged [producers] Arthur Kramer and Mike J. Frankovich to get it for me. Frankovich said they'd go to $75,000. Well, I was at a party and they told me the bad news: Marty Ransohoff had bought it for $150,000. A couple of days later they made the deal with him to produce it, and of course they took on the $150,000. The old story: they were afraid someone else might do something.

Ransohoff was crazy about the book. There were no changes. It was an unorthodox script because it was an unorthodox book. It had a chance to go, and I liked an actor named Robert Redford, who had then been in two pictures, and Marty talked to Redford, with [director] Arthur Hiller. I think Hiller would have been good because he'll shoot the script and he's a very good director of comedy—and there was wild comedy. Marty could have put it together for $3.5 million, but neither Columbia nor Paramount would do it.

Finally Burt Lancaster wanted to do it and they spent over $8 million, and lost it all. They shot the picture in Yugoslavia, which I thought was a mistake

* Castle Keep is a World War II melodrama, based on a William Eastlake novel, that stars Burt Lancaster and Peter Falk. It was directed by Sydney Pollack.

because I had never seen a good picture come out of Yugoslavia, and I'm not sure I have yet!

There was a scene on the rewrites. I was in my agent's office in Westwood and I said, "I want you to call Ransohoff and tell him the following: Dan figures it'll take two weeks and he wants $100,000."

Screaming over the phone. "Or he will do it for guild minimum"—which was about $350 a week then—"but you have to shoot what he writes." The screaming over the phone got louder!

To hear you talking, the disappointment was getting to you .

There was another fine novel Columbia got for me, The Ordways, by William Humphrey [New York: Knopf, 1964]. But before I got into that, Frankovich asked me to do him a big favor. There was a picture in trouble, a Western, Alvarez Kelly [1966]. It was a very serviceable script, but it needed juicing up. But that was another crazy trip down to Baton Rouge, Louisiana. I was writing either in front of or behind the cameras—I never could determine which. They were out in the field with a bunch of cattle and I was in a motel, and I would write the scenes and then see the rushes end up saying something different. I said to Eddie Dmytryk, who was directing, "What is the sense of my sweating out this dialogue if you're gonna let Bill Holden ad lib whatever he wants to say?" And he said to me, "Dan, you take the script too seriously." Holden was in a strange state then. He was on alcohol a lot. We would meet in Bill's room after the shooting and go to dinner. Bill would drive so erratically I would just shut my eyes. A couple of years later a man got killed in Italy.[*]

Then I came back and did The Ordways . But I was stumbling into troubles now. I go over to Fox, there's nobody there. Now, the Bank of Paris was trying to take over Columbia. So Columbia was worried about their stock and they didn't make any movies. I don't know whether The Ordways had a chance—it would have been an odd picture—but it didn't get made.

Guy McElwaine then was supposed to be my agent, and I guess he was for two weeks. Then he turned me over to Arlene Donovan at ICM. She called me and asked if I'd like to do a big book about the Mexican Revolution, The Adelita by Oakley M. Hall [Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1975]. The Xerox copy weighed about eight pounds, but I liked it very much. [Producer] Marty Bregman owned-it, or had an option. I wrote a first draft and Bregman seemed to like it. He and [director] Sidney Lumet and I met and Lumet loved what I had done—and Lumet hadn't liked the book. But he said, "Unless you do it the way I want, I really can't do it." I didn't want to start over, and neither did Bregman. Lumet was talking of doing it in Spain with Al Pacino.

* See Golden Boy: The Untold Story of William Holden by Bob Thomas (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1983). Valerio Giorgio Novelli was killed on July 26, 1966, after his Fiat was struck from behind by a silver-grey Ferrari driven by Holden on the autostrada between Florence and the Tyrrhenian coast. Charged with manslaughter, Holden received a suspended sentence in an Italian court.

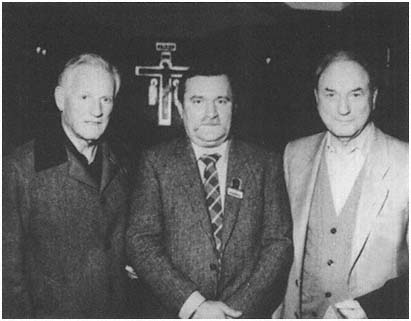

Work in progress: pictured for publicity purposes (from left), director Stanley Kramer,

Polish labor leader Lech Walesa, and writer Daniel Taradash, in 1987, planning a

film about Walesa's life.

But somehow it never happened. Suddenly one day, a year or so later, I got a call from Marty and he said he was going to make it now. He wanted Richard Sarafian to direct it. But it involved taking out another character. I said, "Well, let me do it sketchily, so we see how it works." But Bregman and I got into a salary dispute, and finally I just sent the script to him. Last I ever heard.

Then I was in Florida and I get a call from Donovan and she said Frank Yablans wants to talk about [Sidney Sheldon's novel] The Other Side of Midnight . I had never met Yablans before, and he was a very vigorous, enthusiastic guy. I said no, because I didn't like the book. Then I came back to California and Ransohoff talked me into doing it. I did it very quickly for me; but I said, I won't show you any pages. One day I got a call from Yablans or Ransohoff, and he said, "Can you please, please, let us see the first 100 pages? Because if we can give it to [Twentieth Century-Fox executive] Dennis Stanfill and if he likes it, we can get $1 or $2 million in advance." So I showed the pages. And they had a lunch. Afterwards, Yablans came back to my office and said, "If you ever work for another producer in this town, I'll kill you." Stanfill had given him the money. I was off the picture about two

months after that. Fired, I mean. They were sort of shabby about it, because I was working over a weekend, patching, and they were talking to other writers, which they weren't going to tell me about at all.

What I guess I'm telling you, and it's beginning to sound like it to me, is a story of early triumph and later chaos. But I think the biggest disappointment of my writing life was that Andersonville was not produced. Andersonville was the Civil War prison camp where, I think, 15,000 troops died. They were out in the sun, completely uncovered. I set it all in the camp and on a plantation nearby and at the Widow Tebb's house. She's a whore, and I wanted Tallulah Bankhead for her, with Fredric March as the plantation owner. MacKinlay Kantor was a strange fellow: he got the Pulitzer for fiction in '56 [for Andersonville ]; but he wanted to get it for history because of the research. He wrote me a six-page letter about inaccuracies in the script—uniforms, regiments, that sort of thing—and then he ended with a great line, "You have the sublime admiration of the original author."