Curt Siodmak (1902–)

1928

Südsee-Abenteuer [director unknown]. Co-script.

1929

Flucht in die Fremdenlegion (Louis Ralph). Script.

Menschen am Sonntag [People on Sunday ] (Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer). Story.

Mastottchen [director unknown]. Co-script.

1930

Der Kampf mit dem Drachen [The Fight with the Dragon ] (Robert Siodmak). Script.

Der Mann der seinen Mörder sucht [Looking for His Own Murderer ] (Robert Siodmak). Co-script.

Der Schuss im Tonfilmatelier (Alfred Zeisler). Co-script.

1931

Der Ball [French version, Le Bal ] [The Party ] (Wilhelm Thiele). Co-script.

1932

Marion, das Gehört sich nicht [a.k.a. Susanne im Bade or, Italian version, Cercasi Modella ] (E. W. Emo). Script.

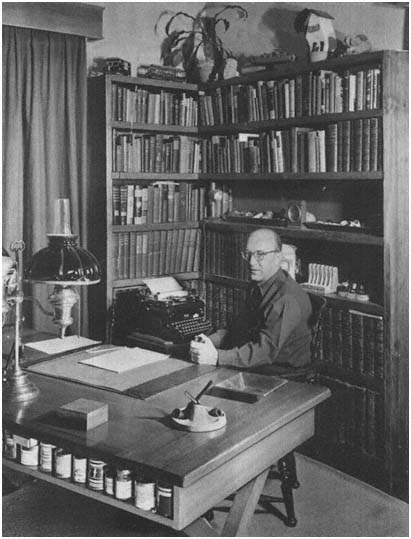

Curt Siodmak in Los Angeles, 1989.

(Photo: Alison Morley)

F.P.1 antwortet nicht [F.P.1 Does Not Answer ] (Karl Hartl). Co-script, based on his novel.

1934

La Crise est finie! [The Crisis Is Over ] (Robert Siodmak). Story, co-script.

I Give My Heart [a.k.a. The DuBarry ] (Marcel Varnel). Co-adaptation, co-script.

Girls Will Be Boys (Marcel Varnel). Story.

It's a Bet (Alexander Esway). Co-script.

1935

The Tunnel [a.k.a. Transatlantic Tunnel ] (Maurice Elvey). Adaptation, co-script.

Non-Stop New York [a.k.a. New York Express ] (Robert Stevenson). Co-script.

I, Claudius (Josef von Sternberg). Co-script, unrealized production.

1938

Her Jungle Love (George Archainbaud). Co-story and idea.

Spawn of the North (Henry Hathaway). Uncredited contribution.

1940

The Invisible Man Returns (Joe May). Co-screen story, co-script.

Black Friday (Arthur Lubin). Co-screen story, co-script.

The Ape (William Nigh). Co-script.

1941

The Invisible Woman (A. Edward Sutherland). Co-screen story.

Aloma of the South Seas (Alfred Santell). Co-story.

The Wolf Man (George Waggner). Story, co-script.

Pacific Blackout (Ralph Murphy). Co-screen story.

1942

The Invisible Agent (Edwin L. Marin). Screen story, script.

London Blackout Murders (George Sherman). Screen story, script.

1943

Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (Roy William Neill). Screen story, script.

I Walked with a Zombie (Jacques Tourneur). Co-script.

The Purple V (George Sherman). Co-script.

False Faces (George Sherman)). Screen story, script.

The Mantrap (George Sherman). Screen story, script.

Son of Dracula (Robert Siodmak). Story idea.

1944

The Lady and the Monster [a.k.a. The Tiger Man ] (George Sherman). Based on his novel Donovan's Brain .

The Climax (George Waggner). Co-script, adaptation.

House of Frankenstein [a.k.a. Chamber of Horror ] (Erle C. Kenton). Screen story based on his "The Devil's Brood."

1945

Frisco Sal (George Waggner). Co-screen story, co-script.

Shady Lady (George Waggner). Co-screen story, co-script.

1946

The Return of Monte Cristo (Henry Levin). Co-screen story.

1947

The Beast with Five Fingers (Robert Florey). Script.

1948

Berlin Express (Jacques Tourneur). Story.

1949

Tarzan's Magic Fountain (Lee Sholem). Co-screen story, co-script.

Swiss Tour [a.k.a. Four Days' Leave ] (Leopold Lindtberg). Co-script.

1951

Bride of the Gorilla [a.k.a. The Face in the Water ] (Curt Siodmak). Director, screen story, script.

1953

Donovans' Brain (Felix Feist). Based on his novel.

The Magnetic Monster (Curt Siodmak). Director, co-screen story, co-script.

1954

Riders to the Stars (Richard Carlson). Screen story, script.

1955

Creature with the Atom Brain (Edward L. Cahn). Screen story, script.

1956

Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (Fred F. Sears). Screen story.

Curucu, Beast of the Amazon (Curt Siodmak). Director, screen story, script.

1957

Love Slaves of the Amazon (Curt Siodmak). Producer, director, screen story, script.

1959

The Devil's Messenger [a.k.a. 13 Demon Street ] (Curt Siodmak, Herbert L. Strock). Co-director, script, based on his story "Girl in Ice."

1962

The Brain [a.k.a. Vengeance ] (Freddie Francis). Based on his novel Donovan's Brain .

Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace [a.k.a. Sherlock Holmes und das Halsband des Todes ] (Terence Fisher). Script.

1963

Das Feuerschiff [a.k.a. Les Tueurs du R.S.R.2.; Der Ueberfall; Ich kann nur einmal sterben ] (Ladislaus Vajda). Script.

1967

Ski Fever [a.k.a. Liebesspiele im Schnee ] (Curt Siodmak). Director, co-script.

1970

Hauser's Memory (Boris Sagal). Based on his novel.

1977

Der Heiligenschein [director unknown]. Based on his story "Variations on a Theme."

1979

Moonraker (Lewis Gilbert). Uncredited contribution based on his novels City in the Sky and Skyport .

Television credits include "Donovan's Brain" (CBS, 1956).

Published fiction includes "The Eggs from Lake Tanganyika," "Sturmflut!," Helene droht zu platzen!, Schuss im Tonfilmatelier, Stadt hinter Nebeln, F.P.1 antwortet nicht [F.P.1. Does Not Answer ], Rache im Aether, Die Madonna aus der Markusstrasse [a.k.a. Downtown Madonna ], Bis ans Ende der Welt, Strasse der Hoffnung, Die Macht im Dunkeln, Donovan's Brain, "Epistles to the Germans," Whomsoever I Shall Kiss, The Climax (by Florence Jay Lewis based on Siodmak's screenplay), The Magnetic Monster (with Ivan Tors), Riders to the Stars (by Smith Roberts, based on Siodmak's screenplay), Skyport, Despair in Paradise, I Gabriel, For Kings Only, Hauser's Memory, The Third Ear, "The Thousand Mile Grave," "Variations on a Theme," City in the Sky, "The P Factor," and The Wolf Man (by "Carl Dreadstone," based on Siodmak's screenplay).

Awards include a Writers Guild nomination for his story for Berlin Express in 1947.

What was the motion picture industry like, in Germany, when you were just starting out?

When I was 27, I worked on a picture called Menschen am Sonntag, and out of that picture came six guys who made it internationally—Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Edgar G. Ulmer, Eugene Shuftan [né Eugen Schüfftan], Fred Zinnemann, and myself. It was a great success. Robert was a film cutter for the Harry Piel detective serial. His job was to compose "new" films from old films of that serial, since the same actors played in both. Robert wanted to be a director. There was Billy Wilder, who was a poor journalist. He picked up a few bucks at the thés dansants, the afternoon tea dances at the hotels where rich ladies went without their husbands in the afternoon. He got tips from those ladies. He was a good-looking young man and an excellent dancer. Zinnemann, whose original name was Zimmerman, was the camerafocus man, a quite nondescript chap who left, after six days' shooting, for America. And there was Edgar Ulmer, who also went to the United States. He now has become a belated cult figure. He shot a great many B pictures for David Selznick. I understand that Selznick treated him very cruelly. As for me—I was already "affluent" since I had sold my first serial novel to the Woche magazine, which paid very well. I gave Robert an idea and 5,000 marks to start Menschen am Sonntag, which was half of the production money.

He brought the picture in for 9,000 marks, which was $2,500 at that time! That film, Menschen am Sonntag, has become a major classic and is mentioned in almost every film anthology. There is a copy at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. That was the beginning of our careers, though actually only Robert and the camerman Eugen Schüfftan were responsible for its completion. Robert and Billy Wilder were engaged by UFA, the Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft, the most prestigious film company of those days, well known for its pictures all over the world. Robert liked Billy Wilder, and when UFA asked for him, he teamed up with Billy again. They took off like meteors.

Wilder has a screenwriting credit on Menschen am Sonntag.

Robert gave him screen credit. I got: "Based on an idea by Kurt Siodmak." I didn't script it. Nobody scripted it.

I had an idea, and the idea was very simple. The story is about a big city full of traffic, like New York or Berlin. A boy meets a pretty girl and makes a date to take her on Sunday to the Wannsee, which is a big lake near Berlin. He brings his best friend; she brings a girl prettier than she is. The first boy goes after the second girl. One boy and one girl stay in the empty city.

The people took the city, with all its noise they wanted to escape, along,

while the couple that stayed behind had a real holiday. That was the frame. That was all we had to begin with. That idea has been stolen many times, as Bank Holiday [1938], which Carol Reed made in England, and as La domenica d'agosto [1949] or A Sunday in August, in Italy. As happened many times in my life, my ideas were lifted. I never got paid for any of them.

We had no money and Kodak donated overaged film, which they would have destroyed anyhow. We devised scenes [day by day] for the next day's shooting. Whatever we had in mind, we talked over. I remember I had a still camera which, I used as a reporter, and I climbed up on the roofs of the big apartment houses in Berlin and photographed the empty courtyards from above, which Schüfftan afterwards used in the picture to show the deserted city.

I noticed that it employed new techniques like the freeze-frame, years before Truffaut, and people who had never acted before, as Roberto Rossellini did .

Robert and Schüfftan did what the French and Italians did thirty years later and called the "nouvelle vague," or the—New Wave. Robert and Schüfftan never got the credit. They did all that years before the New Wave.

I gather there was always some sibling rivalry between you and your brother . There was tremendous sibling rivalry, though we were the best of friends. As a director, he was paid a day what I made a week, but we both lived well. One day it dawned on me that I had a "brother complex." The term "brother complex," like in psychoanalysis, solved that question for me, and all of a sudden our competition became funny. But Robert never understood it. It went on until he died, in 1973. I still cannot figure out his lifelong "sibling" jealousy, since he had a tremendous career and made internationally famous pictures. It might be, since he was the firstborn, that I, two years younger, deprived him of much of our mother's love. Those reasons seem to be irreparable in people's lives.

My brother and I started in the film business writing German "intertitles" for Max Sennett comedies. But I wanted to write novels and short stories, and he wanted to direct. He wanted to be the only Siodmak in films, and asked me to change my name to Curt Barton. The Curt I accepted, the Barton I didn't. You never know what goes on in people's minds. Still, he helped me all my life when I was in a squeeze, which often happens to writers, and I helped him. Looking back, I supplied many of the ideas which made him well known, here and in Europe. But we rarely worked, together. I wouldn't take orders from him and vice versa. He was a very complex character whom only psychoanalysis might be able to explain.

Of course, his and my behavior came from our family background. We never had a "real" family which would supply the love children thrive on. My parents' marriage wasn't a happy one, and though we were brought up in our early life with governesses in an affluent surrounding, we were rebels and left the family at a very early age. Robert started as an actor; and I, while

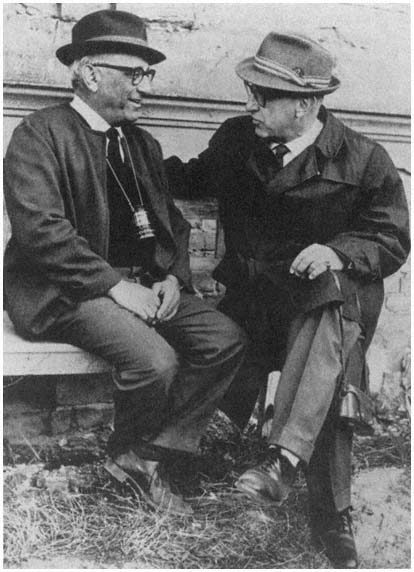

"Sibling rivalry": director Robert Siodmak (with viewfinder) and writer Curt Siodmak,

in 1962, during the shooting of Robert Siodmak's feature, Tunnel 28/Escape

from East Berlin, in Germany. (Courtesy of Curt Siodmak)

studying mathematics, which is perhaps the basis for my writing science fiction, drove a steam engine for the German railway and worked in factories to make a living.

Robert was a star-maker. He could work with difficult actors as no other director could. He made the unknown Burt Lancaster a star in The Killers, gave Ava Gardner her first lead, found Ernest Borgnine, and other future stars. . . . I heard Tony Curtis tell this story on television: Robert was shooting a picture called Criss Cross [1949] when he picked Tony out of a group of extras to dance with Yvonne De Carlo. He took close-ups of Tony. Universal put Tony under contract, and the rest is history. But as soon as Robert's discoveries became stars, he wasn't interested in them anymore.

He did do a second picture, The Crimson Pirate [1952], with Lancaster. But he had trouble with Lancaster, since his manager, Harold Hecht, wanted to take the picture away from: Robert, to give Burt a director's credit. It is uncanny that every actor to become a director. They try it, but mostly only once, like Marlon Brandoin One-Eyed Jacks [1961] and Lancaster in Apache [1954].[*] Then they learn how much less work it is to act than to direct, and they lose that desire.

Robert was a top director in Germany. When he the could not work on account of the Nazi persecution in Berlin, he went to France, where he 'also made highly successful films. He sailed with the last boat from France to America the day World broke out. You know about his career over here. Then he went back to Germany after the war, because he was too independent to take orders from studios. There again he got many Bambis, which are the German Oscars.

He was excellent when he got a screenplay which he had to start in a few days, and when he had no time to mess with it. But maybe since I was successful as a writer, he had to prove to himself that he was not only a great director but also a great writer. He could tell a scene so vividly that you would say: "My God, what a marvelous scene!" But, unfortunately, that scene didn't fit his picture. To be a writer is quite different a profession than to be a director or producer.

After Menschen am Sonntag, Robert and Wilder were engaged by UFA .

Yes, but actually: didn't want them. They got their salary but no assignment. Meanwhile, I wrote a twelve-minute screenplay Der Kampf mit dem Drachen [The Fight with the Dragon, 1930], the story of a lodger who kills his landlady because she is so mean. It was a surrealistic tale, and the big shots at UFA, without reading it, let Robert shoot it in two days. When they saw it, the staid UFA bureaucrats became—panicky, since it was abstract and unconventional. It was only shown in the Berlin suburbs as a filler for one of UFA's prestige pictures.

* Robert Aldrich directed Apache . Siodmak probably means The Kentuckian (1955), the only film Burt Lancaster directed.

A scene from the 1932 German film F.P.1 antwortet nicht. Walter Reisch and Curt

Siodmak both worked on the screenplay. (Photo: British Film Institute)

Since Robert's name as the director of Menschen am Sonntag was interesting to the press, the reporters drove specially out to the suburbs and wrote glowingly about that short instead of the new UFA film. Robert was an excellent PR man for himself. He showed the short film to the secretaries and mailboys at the UFA studio. Erich Pommer, who was the greatest producer I have ever worked for, too was present, and I saw him for the first time. Pommer's productions ranged from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari [1919] to the Emil Jannings pictures. When Pommer saw that short, his eyes became as big as wagon wheels. He took Robert and Billy into his production.

I was working on a UFA screenplay assignment, Der Mann der seinen Mörder sucht [Looking for His Own Murderer ]. Pommer took me and my half-finished screenplay into his production. Whatever I know about motion pictures, I know from him. We worked in his villa at the Wannsee, an exclusive part of Berlin. Pommer worked with writers on two or three different productions at the same time. After one conference, he went to another. Mörder sucht too has become a kind of classic, since it gave Heinz Rühmann, a young comedian, his first part. Rühmann became the foremost German comedian for decades. He even thrived under Hitler.

After F.P.1 Does Not Answer, you left Germany. Could you see the handwriting on the wall?

I didn't have to see it. I received a letter from the National Socialist Cham-

ber of German Writers informing me that I was not going to be permitted to write for any German publisher or motion picture company.

What year was that?

1933. When I think back, I wonder how I and my wife survived that time. It is so long ago! But still, it is a nightmare to me. I gave a speech once at an American high school and a boy shouted, "How old are you?" I said, "I'm forty-eight and my wife is forty'six, and my son is fifty-three. Because forty-eight years ago I came to America. . . . I had to learn a new language, which isn't easy for a man who makes his livelihood writing. I had to start from scratch. This day of coming to America was the day of my second birth. To emigrate is like starting your life all over again."

From Germany, I went to France and tried to make a living, which I couldn't. Then I went to England and was quite successful over there—making good money writing for British International films and Gaumont British. But I was always older than anybody else, because when I went to England, I was thirty-one, and I started working with twenty-years-olds. When I came to America I was thirty-five, and again I started working with the kids. So I always integrated myself with the young generation, which is a plus.

Did you have some trouble in the British film industry? Is that why you left for America?

The British Home Office threw me out overnight, because my labor permit had run out. I had to leave in twenty-four hours and couldn't come back. I went to France. But I had given a story, "For Kings Only," to a lovely English actress, Frances Day. She convinced Gaumont British to take an option on it, which permitted me to return to England. That story was never made, but I received two hundred pounds for the screenplay of The Tunnel [Transatlantic Tunnel, 1935]. It was the first British film that used American actors: Richard Dix, Madge Evans, Fay Wray—the girl from King Kong [1933]—and Walter Huston. I got a year's contract, and fifteen pounds a week, which at that time was good money. I paid two pounds a week rent for a house. Henrietta and I bought gold pieces and counted them at night, putting them in stockings under our pillow. They became the basis for my trip to America. It was Henrietta who wanted me to go to America. I guess she felt the war coming.

I got a job the first week I arrived in Hollywood. An agent took me to Paramount studios. I disliked the story editor, Manny Woolf. I called him the Jewish Charles Boyer, which shocked him, because he had these dark eyes and this sexy voice. He signed me up for a big picture for Dorothy Lamour [Her Jungle Love, 1938]. (Sings .) "Moonlight and shadows and you in my heart . . ." That song, incidentally, was written by Friedrich Holländer, who wrote the songs for The Blue Angel [1930] and Looking for His Own Murderer .

I rented a house, engaged a Filipino servant, bought a Buick convertible, the usual stuff of Hollywood success. And all the girls! I was here alone for

almost a year. All the pretty Hollywood girls would come to the house. I always had a case of Scotch, Old Rarity, in my bar, to be sure to find some friends when I came home from the studio. Henrietta arrived and I had to tell the girls that I had a wife. From that time on, my guests were mostly male.

Was there much of a German colony in Hollywood, as there was a British colony?

To begin with, yes, of refugees. But then we worked with American actors and American writers, and that group dissolved. The successful ones separated from those who couldn't make it. Many refugees couldn't adjust themselves to the American mentality. They never learned to write in English, or perhaps they didn't want to give up their German language. Thomas Mann wrote in German, Brecht and Remarque wrote in German. When you live in a new country, you have to be reborn, learn what the natives know, integrate yourself; otherwise you will never be a part of that country.

How did you get involved in the Invisible Man pictures [ Invisible Man Returns, Invisible Woman, Invisible Agent],which you began working on in 1940?

When Henrietta came over here, I lost my Paramount job and didn't get a job for eleven months, though I sold a story called Pacific Blackout [1941] to Paramount, which helped me stay alive. Then Joe May, who was a friend of mine, directed a picture at Universal [The Invisible Man Returns, 1940]. He pushed me through to write the screenplay. It was the first picture for Vincent Price, as a young man.[*] Although I had only written comedies and musicals for Paramount, this was a success, and I fell into a groove. At the studios, if you have a success in a special kind of picture, you are condemned to getting similar jobs, and soon I had to write only horror pictures. Your mind changes, too. You are brainwashed.

You wrote so many horror pictures. Not only the Invisible Man series, but The Wolf Man [1941], Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man [1943], Son of Dracula [1943], and many more. There must have been something latent in the subject matter which you found congenial to your sensibility .

The fantastic and macabre is a "German" trait. Look at their fairy tales, which are pretty gruesome. But we writers are known for our successes, and mine were in the horror field. But among the novels I wrote was lighter Stuff, like, for example, For Kings Only, a semihistorical story of Hortense Schneider, Offenbach's leading lady, during the world exhibition in Paris in 1867. It has a musical background. Then many space novels and adventure stories. A writer has to be versatile, and among my output (about sixty motion pictures and a score of novels) is much material which cannot be classified as horror.

We refugees suffer from the past, the Hitler persecution, which we will

* In reality, Vincent Price had previously appeared in Service de Luxe (1938), The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939), and Tower of London (1939).

never be able to absorb completely. We were often so close to death that we are branded for life. No success could wipe out the past which we went through. The play I have just finished, Three Days, shows the background of those terrors in my life which might have found an outlet in writing horror stories. But certainly not the modern kind, which in my opinion is vulgar in its spilling of blood. I don't think I ever wrote a truly violent scene. I left the horror to the imagination of the audience.

There was a fair amount of humor, also, in the second "Invisible" picture, The Invisible Woman [1949.] .

That was a spoof about the Invisible Man series. John Barrymore was in it. He was so gone with alcoholism that we had to hang him up with wires so that, in close-up, he wouldn't sway out of focus. . . . He had his dialogue written up and down a staircase on cue cards, so that coming down he could read his lines. I think it was his last picture before he died.

The Wolf Man is certainly a classic. It has this fairy-tale timeless feel about it. It's not set in the past or in the present day. It's set in a Europe that never existed. It has a bit of poetry in it .

It even goes much deeper than that, though I didn't know that when I wrote it. One day many years ago, I got a letter from a Professor Evans from Augusta College in Georgia about the parallel between The Wolf Man and Aristotle's Poetics, which is a critique of Greek plays. I thought the guy was nuts. Not true. In the Greek plays, the gods reveal to man his fate; he cannot escape it. The influence of the gods over man is final, and that's like the domineering father the character has in The Wolf Man . He knows that when the moon is full, he becomes a murderer. That is his preordained fate.

The film was constructed like a Greek tragedy, without my intent at the time, but it fell into place and that's why it has run for forty-eight years. I made $3,000 on the job. They have made, so far, $30 million on the picture.

We writers don't think, actually. We do things out of emotions and constructions in our mind as to how a character or a story should develop. There's a story told about Balzac. A friend found him in tears and asked him the reason. Balzac said, "Hélène died." Hélène was one of the characters in the story he was writing; she had died and he was breaking out in tears.

How can you teach aspiring writers? You can teach technique, like screenplay technique, but you cannot teach emotions or how to find ideas. God has to kiss your forehead, and that's why I am bald, to leave as much room as possible.

With The Wolf Man, I know you did a lot of research. Did the research inspire any particular ideas?

Well, in all of my writings there is tremendous research involved. Wolf madness, lycanthropy, goes back to the Stone Age. People wanted to become as strong as the strongest animal they knew of, which was the wolf in Europe, the tiger in India, the snake in the Pacific. Man tried to identify himself with the strongest animal he knew.

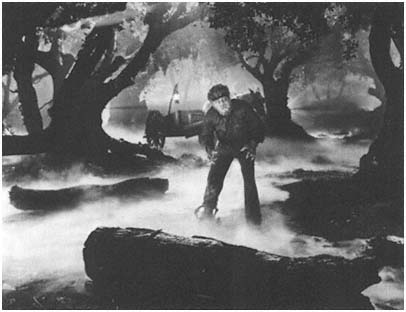

"Like a Greek tragedy": Lon Chaney, Jr., in the outstanding horror film, The Wolf

Man, script by Curt Siodmak, directed by George Waggner.

(Photo: Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

I remember how that film was initiated. Universal director-producer George Waggner said to me, "We have a title called The Wolf Man . It comes from Boris Karloff, but Boris has no time to do it, he is working on another picture. So, we have Lon Chaney and we have Madame Ouspenskaya, Warren Williams, Ralph Bellamy, and Claude Rains. The budget is $180,000 and we start in ten weeks. Good-bye . . ."

After seven weeks I gave George the screenplay. I don't think he made any changes, except to telescope a few scenes to save sets.

I've noticed that your early horror films seem to be more science fiction films with gothic touches. For example, The Ape [1940] became one of the first "bring me the spinal fluid" films . . .

That was at Monogram studios. Maris Wrixon, [who played] the blind girl, is now editor Rudi Fehr's wife. I sometimes see them. She likes to talk about that early film with Karloff. We were groping around for new ways of presenting my stories.

In addition to horror stories, you also scripted a number of jungle pictures .

They were actually assignments. Mostly there was only a title. Almost all my films were based on original ideas. I don't know how I thought of all those stories. I've been asked, "How do you get your ideas?" "Very easy," I say, "My weekly check."

How did you get started on the Frankenstein films once they restarted those up in the forties?

I was at Universal, writing other "Invisible" stories for the same producer. I was in the groove. He would say, "Give it to Siodmak; we'll get the script and we can shoot it in a few weeks." That was my reputation. It has nothing to do with the value of things., it was that they knew they wouldn't lose money.

Was it your idea to start combining monsters in films with Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man?

That idea started with a joke. I was sitting at the Universal commissary during the war with a friend of mine who was drafted and wanted to sell his automobile. You couldn't get an automobile in those days since those companies only turned out war material. I wanted to buy that car, but I didn'thave the money.

George Waggner was sitting with us, and I made a joke: Frankenstein Wolfs the Meat Man, I mean, Meets the WolfMan . He, didn't laugh. He came back to my office a couple of days later and asked, "Did you buy the automobile?" I said, "For that I need another job." He said, "You have a job. Frankenstein Meets the WolfMan . You have two hours to accept." That taught me never to joke with a producer.

But then you needed a gimmick for the story. And the gimmick was that the Wolf Man meets the Monster and both want to find Dr. Frankenstein, because Victor Frankenstein knows the secret of life and death. The Wolf Man wants to die, whereas the Monster wants to live forever.

I always put a funny scene in my scripts because I know that the director didn't really study my script before shooting. There was a scene in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man where the Monster walks along with the Wolf Man and the Wolf Man says, "I change into a wolf at night. . . ." And the Monster says, "Are you kiddin'? . . ." When they broke the screenplay down on the shooting schedule, they finally read it and threw that scene out.

A strange thing about that film is that the Monster is supposedly blind from the previous film; so for the first time he walks around with his arms outstretched. But there is no reference to his being blind in the movie .

That was the idea of Bela Lugosi. Listen, you ask me so many questions, I don't know the answer to half these things anymore. People find so many secret meanings in my writings which I never intended. It's true. Sometimes the critics point them out and the writer is surprised. We just wrote stories for the weekly check. But we did the very best we could. There are 100,000 words in the dictionary. What the writer is paid for is to find the right ones. That knowledge makes him a writer.

One of my favorites of the ones you've been involved in is I Walked with a Zombie [1942] .

Yeah, that was interesting. The producer Val Lewton was a marvelous man

to work for. He was erudite. I mean, really knowledgeable. He understood what the writer was saying.

I remember I had a friend named George Froeschel, a writer, who got the Academy Award for Mrs. Miniver [1942]. Once we were talking about a script to producer Sidney Franklin. He is dead now so I can tell the story. Franklin was paid $5,000 per week, which in those days was a tremendous amount of money. When we came out of his office, George said, "Isn't it marvelous? Franklin understood what we were telling him!" I said, "That's very funny. Here's a man getting $5,000 a week and we only get $500 a week, and he understood what you're saying and you admire him for it." We looked down on those people. . . .

Irving Thalberg once said: "The most important man in the motion picture business is the writer. Don't ever give him any power!" Even today the writers are oppressed. Even today a writer gets little appreciation. That's why good writers become writer-directors, or writer-producers, to get more standing, and of course to make more money. I haven't met a writer yet who owns a yacht like producers or directors. But don't let them kid you. Where would they be without writers?

One of the striking things about I Walked with a Zombie, apart from its horrible title, was that it gave off a feeling that death is everywhere—in beauty, in life itself. I find the film very poetic. There's also a very fatalistic approach in that something is cursing this family .

They made changes in the script. My idea was a little different. I started with a beautiful wife married to a plantation owner on one of the voodoo islands. The husband knew that she wanted to run away from him. He would not let her go. So he turned her into a zombie. He could continue to have an affair with her beautiful body. But it was like sleeping with a lifeless doll. I said to Val Lewton, and he laughed about this: "She has no vaginal warmth." This idea—you only need a trickle like this—shows the whole character of the woman. That's why she walked around like a zombie. She was in a living death. But I don't know if they kept it this way. I never saw the picture after it was finished.

You should see it sometime. Lewton made it more like "Jane Eyre in the tropics ."

Right, with Frances Dee and Tom Conway. He died terribly poor.

Did your brother take you off Son of Dracula?

Yeah. I finally got him a job on a film I had written, and the first day he starts working with another writer, Eric Taylor. I understand that, because, between brothers, who is going to have the authority? He was very unhappy taking the job. He had to accept $125 a week. But after two years he was pulling down $1,000 a day! I never made that kind of money as a writer. No writer in Hollywood did at that time. Only directors, producers, and actors.

Boris Karloff returned to the screen and made his first color picture with The Climax [1944], which seems designed to reuse the sets from Phantom of the Opera [1943].

Well, that was my idea. The idea was that Boris Karloff had a big love affair with an opera singer and killed her in a fit of jealousy. He kept the body somewhere. When he visits a conservatory, he hears the same voice again in a young girl. I wrote it for Susanna Foster, I remember that. And around that idea, I wrote the screenplay. For every story you need a sharp idea which you should be able to write on a postcard. A friend of mine sold stories that way, like: "There is a terrible housing shortage in Washington during the war, and a rich, young couple has the idea to hire themselves out as butler and maid in the house of an important government official . . ." That was the "weenie" and that was all it took to get him a job in a studio.

I've heard that [director] Robert Florey and Peter Lorre were not terribly happy with The Beast with Five Fingers [1947]. Did you ever get much feedback from them?

That is all baloney. I wrote The Beast with Five Fingers, not for Peter Lorre, but for Paul Henreid. Paul said, "You want me to play against a god-damned hand? I'm not crazy." I would love to have shot it with him, because I thought a man looking so debonair was a much more interesting murderer than that freakish Lorre. [Luis] Bufiuel says he was involved in the story. I never met Buñuel, nor did I see any other script on that subject.

I believe Buñuel said somewhere that he wanted to be involved, not that he was .

Who knows, he might have done an interesting job. I remember Bill Jacobs was the producer and he called me in to talk about that story. I had the idea that the murderer had a guilt complex, so the hand of the murdered man comes to life in his mind and kills him. That made the picture.

Oliver Stone lifted the same idea for The Hand [1981] .

Sure, all my stuff has been stolen many, many times. I can trace them when I see them. Did you see that Steve Martin made a picture called The Man with Two Brains [1983]? In the picture they showed cuts of the film Donovan's Brain on a television screen, but they never asked my permission. If I ever meet this director, Carl Reiner, I would say to him, "I'm a poor writer. You take the story, you take the idea, you show the idea on the screen, and you never gave the writer credit. . . ." Because they have the money and I don't have the money. I'm not going to put my good money into lawyers. They have a battery of lawyers and could drag the case out for ten years. I haven't got ten years. It's depressing, the power money has over creativity. I never thought of money in my life when I was writing. I would like to have more, of course, but I don't know the game. I'm writing a play now, and that takes my whole time. Compulsives. We can't help it.

Despite the fact that your most famous work is Donovan's Brain, you've never scripted any film versions of your own book. Why is that?

Well, I was always busy with something else.

I have here a book by Stephen King. I never met him. He wrote Danse Macabre . In it he talks about Donovan's Brain . He gave me the greatest writeup I've ever seen. "Nobody has ever written a book like that." So I wrote to him, "Please send me your autograph, to put in that book of yours." Big case came with all the books he had ever written, every one with a dedication! Only writers do stuff like that. They're human beings.

Donovan's Brain has been done three times. First, there is The Lady and the Monster [1944]. I sold Republic the rights, back then, for $1,900. Old man Herbert Yates, the owner of Republic studios, called me and said, "Siodmak, you're crazy!" I said, "Why am I crazy?" He said, "A scientist of that size . . . he should live in a castle. I have a title for the picture—The Lady and the Monster . Vera is going to play that part; she'll play the Lady." Vera Hruba Ralston, a former ice skater, was his girlfriend and later his wife. So I quit.

Then I started with producer Allan Dowling, who bought the rights from Republic and made it with Lew Ayres, Gene Evans, and Nancy [Davis] Reagan, and with Felix Feist as the director. I had lunch with Nancy Reagan when she was twenty, before she married Ronald Reagan. In Feist's version, God destroys Donovan's brain with a thunderbolt. So I didn't see the picture [Donovan's Brain, 1953].

They did it in England again and it was done by . . .

It was directed by Freddie Francis as an English-German co-production in 1962 [ The Brain, with Peter Van Eyck, Anne Heywood, Cecil Parker, Bernard Lee, Frank Forsyth, Miles Malleson, and Jack MacGowran] .

Yeah, they added a cancer cure to that version, and I didn't see why.

They used it as motivation for someone close to Donovan who would want to kill him, because he was withholding this vital cancer cure .

Then why buy the book?

Well, for the most part, it does follow your book very closely; it just changes the motivations and some other things around .

Silly. The smartest guy in the whole business was John Huston. We started together, though actually he made it bigger than I did. He got The Maltese Falcon [1941] and he went to screenwriter Allen Rivkin and he said, "How do you write a screenplay?" Allen Rivkin took the book and telescoped it, just by marking the scenes. Huston shot it exactly as Dashiell Hammett wrote the book; didn't change the dialogue at all; everything was there, and he had a smash picture. If something is a success, why change it?

I used to know the whole gang in the old days. I used to play chess with Humphrey Bogart, but I couldn't afford it.

Why is that?

He went through my bottle of Scotch in one sitting. John Huston was a very interesting man. He could recite Shakespeare, the whole of Shakespeare, when he had a few drinks. I knew all of his wives. If I could live it all over again, I would like to live his life. I wouldn't smoke as much as he did. I asked him once, "What kept you alive?" and he said, "Operations."

Your first film as a director was Bride of the Gorilla in 1951. What prompted you to take that risk, to segue from being a screenwriter to being a director?

Jealousy. Because my brother was a good director; I wanted to show that I could do it too. When I got that first picture to direct, he came shooting down to my house from the hill where he lived and he said, "Don't do it, you'll never be able to." His wife came too and tried to talk me out of it.

It has a few interesting ideas in it, but it looks as if the film was never properly financed .

That was the first time I directed. Seven days of shooting for a full-length picture! The idea wasn't bad. There is a man who commits a murder, but he cannot cope with his guilt. Since an animal can commit murder without being punished, the man thinks of himself as an animal. However, they decided that whenever he looks into a mirror, he should see a gorilla. I thought he should see himself in animal form, but certainly not as a gorilla. They forced me to cut in the gorilla. My title was The Face in the Water . I never wanted to call it Bride of the Gorilla .

He lives in the jungle with animals, since he considers himself an animal and not a human being. I had Lon Chaney and Raymond Burr. They obviously didn't like each other. They looked at each other and sparks flew out of their eyes. Since Lon played the policeman and Ray the murderer, it was just perfect. I didn't have much to direct.

I understand that Lon Chaney was an alcoholic at that time and that he suffered from a difficult and tragic childhood .

Yeah, very tragic. His father, Lon Chaney, Sr., must have been a beast. He beat Lon up for nothing. Sent him to the shed to get the leather strap to be beaten. Sometimes even when Lon hadn't done anything. Lon told me his story. A terrible shock from which he never recovered. When I shot television with him in Sweden, he drank on the set in front of the crew. I stopped him. What he was looking for was a father figure, who would tell him what to do. That is why he was so good in Of Mice and Men [1939].

Riders to the Stars, in 1954, was a very strange film, with the science being really off .

Don't blame me for that! [Producer] Ivan Tors had that story and I wrote it for him. There was no money for decent special effects, I guess, or the picture would have looked much better.

The Magnetic Monster [1953], also for Ivan Tors, was an interesting science fiction film for the fifties because it was much more realistic than most

of the films and it had an offbeat and different premise. Of the films you directed, it's my favorite .

Me, too. I shot the computer scene at UCLA, in a hall filled with gadgets which made up the immense computer. That was before transistors were invented. Now you can buy the same computer, even better, for seven dollars.

The story was that Andrew Marton, the best second-unit director in America, who also directed King Solomon's Mines [1950] and shot the chariot scenes in Ben Hur [1959], returned from Berlin with ten minutes of special effects from a German Nazi film called Gold [1934, directed by Karl Hartl], which must have cost millions. He and Tors came to me to write a screenplay around those shots, which were of a gigantic atom smasher which at the end exploded. That's how it started.

We formed a corporation. Tors got the money from United Artists. We shot the film for $105,000! We made very little money on that film. My ideas, as usual, were premature. The Andromeda Strain [1971] had the same idea twenty years later. It made millions. Also, our title was silly. United Artists, which released that film, put that one on. But it got a half-page write-up in Time magazine, and it became the prototype of many future science-fiction films.

I noticed that it was intended to be the start of a series about an Office of Scientific Investigations .

Yes, that's why we started that company, A-Men, for Atom Men. Tors went to New York to United Artists with The Magnetic Monster and came back and told us that they didn't want Siodmak, they didn't want Marton or Richard Carlson, who was the lead in that picture. They only wanted Ivan Tors. Ivan was a very good salesman for himself. He had big successes with "Flipper." He died tragically in the jungles of the Amazon of heart failure.

After I made an underwater TV pilot called "Captain Fathom," Tors saw it and came up with "Sea Hunt." Look, I'm an idea man. That kept me in bread all my life, not because I speak the language better than anyone else. Everywhere I worked they paid for the ideas. Then other people lifted those ideas, because they had none of their own. They are smarter than I in one respect: they know, like Tors, how to find the money for the productions. I couldn't be bothered with that.

I know that for Earth vs. the Flying Saucers [1956] you adapted the book Flying Saucers from Outer Space by Donald E. Keyhoe [New York: Holt, 1953]. But the final script is credited to two other people [George Worthing Yates and Raymond T. Marcus]. Were you originally going to be more heavily involved?

I never heard about or met Marcus. Yates was desperate to get a screen credit. Just before he died, he wrote a nice letter to me, apologizing that he fought so hard to get that credit. It really didn't matter to me. I wrote that script for producers Sam Katzman and Charles H. Schneer. It certainly wasn't

based on Keyhoe's book. Katzman was too stingy to buy any book. Funny enough, they still talk about that picture. It was a milestone, too. Charles E. Schneer did a number of pictures in the same vein. He destroyed nearly every big city in America on the screen.

I remember that a number of kids who went to see your film Curucu, Beast of the Amazon [1956], were disappointed to discover at the end of the film that the monster was really a native who was pretending. It really seemed like a cheat .

It was done in Brazil for $155,000, and I had a near nervous breakdown when I returned with the finished picture. Nobody had ever shot a picture in Brazil and brought it home completed. It was a tough job, and I have never really recovered healthwise from it.

Beverly Garland certainly has an interesting screen presence .

She was such a good trouper! To run away from her husband, an actor, I understand, she went as far away as she could. That's why we got her for Brazil.

We made masks of the leading actors, John Bromfield and her, since I had a second unit going to Argentina to shoot the gigantic waterfalls. They wore Beverly's and John's masks, and I kept my actors in Brazil. It worked. But making the masks was tough. They stick straws in your nose so that you can breathe, and then lay on some goo. I couldn't do that; I have had a fear of suffocation since I was a child. But she did. Since Carolyn Jones had done it, it became a competition, and Beverly said, "If she can do it, I can do it too."

What is this thing, Love Slaves of the Amazon [1957]?

That was a mess-up. I was responsible. I let Don Taylor influence me, making it a kind of comedy. It should've been a sexy horror picture. I had a pool and we were going to show those beautiful girls swimming naked under the water. But they put the water in too early, the algae came up, and we couldn't shoot it.

The idea wasn't bad: A young scientist, Don Taylor, is captured by the Amazons. He is the only man among them and sleeps with all those beauties, but they give him something to drink, and he has no memory of the past. So what's love good for if we can't remember? I could bring in only 40,000 feet of film for the whole picture, which I did for Universal, because Universal wanted to convert their cruzeiros, which they couldn't take out of the country, into film. You couldn't import any film stock, I don't know if by law or why. And you had to develop the film in Brazil, only it was color film and they didn't have a color lab. How could I develop a color film when there was no lab?

So I had to smuggle the film out. I had rocks in film boxes, which I kept in my hotel, to keep officials, keeping an eye on the production, from becoming suspicious. Ruby Rosenberg, the production manager, who died later during the shooting of Mutiny on the Bounty [1962], wanted to take the film over

and become the director. One day, I asked him how much film was left. He said, "10,000 feet." I wasn't even half through. I said, "What now?" He said, "You have no more film. You go home." I said, "You so-and-so . . ." So I rehearsed every scene, took one take; I never saw dailies and just knew I could never forget a shot. Somehow, I got through the whole picture. Anyhow, Love Slaves of the Amazon is still running on TV. They got their cruzeiros out with interest.

You only directed once again, ten years later, with Ski Fever [1967]. Were you glad to get out of directing?

Of course, yes. I don't like that. Of course, but it is where the money is, the glamor is. "Good morning, Mr. Siodmak? You feel well? You want a glass of orange juice?" Nobody ever asks the writer that.

What was the connection between your book City in the Sky and the James Bond film Moonraker [1979]?

They bought the book because there were two gags in it which they badly needed.

Which were the two gags?

Well, at the end of the film James Bond is making love to that beautiful girl in zero gravity. That was in my book; and also the rotating space station that stops spinning suddenly and all hell breaks loose, everything and everybody starting to float freely. Maybe they used some more. They owned the novel and could do whatever they want with it. Every minute of shooting costs $225,000, so they paid me for twenty seconds of this picture. For me, it's a lot of money. I still have that money. Everything is relative.

You don't seem to take your screenwriting seriously .

I was never married to it. Screenwriting is a sideline for me. I did it just to make money, because I'm one of the few screenwriters who was destined to write books. William Faulkner did the same: He worked for MGM as a screenwriter to be able to afford to write Sanctuary .

I have a trick with writing sci-fi—For Kings Only and Hauser's Memory and City in the Sky . In all these books there is a tremendous amount of research involved. I pick up the telephone and call the most important scientist I can think of in that field in America. So far they have all worked with me because they all are frustrated writers anyhow. If someone is writing [a book] for them, then they can correct it, which makes them feel they wrote it. I siphon off years of knowledge and research from those people for a small fee, or for a percentage of the book, whatever the case. But at the end, I have a story that is scientifically right.

You would be surprised at the names of those people. They go up to the Nobel Prize winners! Some of my books, basically, are based on science. There aren't many science fiction writers in America like me anyhow. There's a difference between science fiction and science fantasy. Science fiction is a

projection of the future as it would happen today; science fantasy is trying out different kinds of social problems and social systems on other stars. Star Wars [1977] and all—this is sci-fantasy.

Since my youth I have written much science fiction about future discoveries which we have now in this day and age and which have become commonplace. I wrote about the laser beam in 1932. I had a book with radar in it in 1931 [F.P.l. antwortet nicht ]. I have a book called The Third Ear [1971] which actually tries to create ESP in people biochemically. Which certainly is possible.

I remember reading in Hauser's Memory that you had RNA (ribonucleic acid) reactivating memory, and I was interested to discover that now research has linked the brain's ability to store information with RNA .

That's right. In researching that book, I worked at this hospital where they had 2,500 retarded children, insane and old people, too. I remember two old guys asking me, "Tell me, sir, are we going to lunch or coming from lunch?" They didn't know which. But they remembered what they had done when they were eight years old.

So we might have a greater amount of RNA—ribonucleic acid—when we are young. As we get older, that substance dries up. That's why we can't learn new languages so easily when we get older, but kids pick it up right away. The growing process of the brain is based on RNA, which is why we learn so fast as kids. Even memory—and also what is right, what is wrong—is information you pick up easily as a child. I find that out now. I'm losing memory slowly. But sometimes you wonder about things, and they come back to you clearly. It might also be that we cut out in later life what is not important from our memory, and only remember what is important, like perhaps having lunch with a pretty girl.

But I'm through with science fiction. The subject has become too esoteric and too far away from my knowledge. You have to study all your life in a certain direction in order to understand part of what they're doing today. I have a compact disc with a laser beam, but who can tell me how it works? I wouldn't know. And so these things have gotten out of my mental reach.

There has been a tendency towards greater specialization .

The present generation is now educated visually, not literarily as we were. They grasp what they see on a TV screen. That's all right. When you see something, something stays in your brain and something drops out. You don't need to think in that respect. As a reader, you have to be logical and understand the written word. Looking at pictures now, and they make very good pictures, the story often falls apart . . . of which the public is not aware, but I, as a writer, see it and suffer.

In what ways have stories changed?

The conflicts have become different. Nothing can shock us anymore, except perhaps bad taste. You ever see Fatal Attraction [1987]? There's a love

scene in there, a sex scene which is funny and wild. The picture I made in Czechoslovakia [Ski Fever ] was about girls in ski resorts who have lost all morals and about some ski instructors who fool around with them. Anyhow, when I came back from working on it, the sex wave had started in America. You could see all those naked dames and couples in bed, of which I could only talk, but never show. The picture was outdated the day it was released. The permissiveness of the audience had turned 180 degrees.

Donovan's Brain, which is still being published—I must have sold five million copies so far—has no sex scenes in it. It's even used in schools as a prototype of science fiction because it doesn't contaminate the children. There are no women's breasts.

I wouldn't know what to write as a motion picture today, except historical themes. I can't sell my novels here anymore, but I sell big in Germany. I just sold my novel The Witches of Paris to Goldmann in Munich—one of my better books, which so far couldn't find a home in America. But you don't go into writing to make money anyhow. If you want to make money, sell condoms to China. One per customer and you will be rich. Why go to the trouble and uncertainties of making motion pictures?

There are certainly plenty of people who create things for reasons other than, or in addition to, making money .

Rarely. It is terrible what the motion picture and the publishing business has become. I remember when I started out and I first met Alfred Knopf—a lovely man. He loved writers. I had an agent, Harold Matson, who got tears in his eyes telling about a book he represented. When you told him about a story you wrote, he really was interested. Today, first, you can't get an agent if you don't make a million already. Second, you send it to a publisher who can't read it. He has little schoolboys reading it.

When I started out in Hollywood, my agent was MCA, which now owns Universal. I had a finished screenplay. A messenger boy picked it up from my apartment. He wore a suit and tie. I handed him the script. Six weeks later it was rejected by MCA (they didn't want to handle it)—rejected by the same boy who had come to pick it up because in the meantime he had become a reader for that company. It's sad how writers are treated with contempt in this business.

Why do you think there is this attitude in Hollywood that anyone can write? The director can write, the producer can write, the actors can write; even the messenger boys can write. [Why this attitude] that anyone can do what the writer can do and therefore the writer has very little status or control?

Well, I'll tell you, it's a conundrum. I may be the worst writer in the world. After I've written it, everybody thinks he can write the same thing better. But I have to write it first!

I would like to take one of those directors or producers and give him a sheet of paper and a pencil and have him come up with a scene and have it

put on the screen. After I've written it, they scribble on it and "make it better," and the damned thing falls apart. Writing doesn't have to do only with a pencil and a piece of paper. Just because you have a violin, you can't play it; just because you have a piano, you can't play it. There are rules and regulations in writing.

Also, we are the echoes of our energies. The more energy we put into work, the bigger the echo; from a love affair to writing, to painting, to anything. You can feel the energy. There is something physical in creation you can almost touch.

But if that energy is not there, all my craftsmanship, which I have now after half a century of writing, doesn't mean a damned thing. I can write a story at the drop of a hat, but it is no good without that energy. There is an inner spring that has to be released, which gives you a response and an echo. This you cannot teach. The producers, except for some rare exceptions, don't have it. They might suggest ideas, but everybody has "ideas."

You will also find out that writers—I am talking about authors like Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Tennessee Williams, Sinclair Lewis, Dreiser, and so on—were all alcoholics . Why alcoholics? As soon as they stopped drinking, they were not good anymore. Because they had some formulations in their mind for which there were no words to express. We writers have that feeling that we haven't reached what we want to say.

The dictionary has a finite amount of words, and that very precise word you want to find doesn't exist. So now, we invent new words which express what we have in mind. I myself have invented a couple of words which express exactly what I want to say. Writers, and I mean the driven ones, are full of frustrations. Writing is a release of frustrations. I've never picked up a book in my life that I've written and read it again. Most of the motion pictures I've done, I don't want to see.

And why is that?

For example, I wrote a screenplay here which might yet be done in Israel, based on my novel The Third Ear . The book was published in '74, and only now do I know a better ending to the book. So you see, we don't ever write the thing we want to write, the perfect thing!

You seem to have been fairly fortunate in your experience as a scriptwriter. At least in the sense that most of your work has been produced and endured .

I only have two screenplays that I have written that have not been done. . . . The others have all reached the screen. The studio wanted dependable writers, and I certainly was one. Universal was always on the brink of bankruptcy and couldn't waste any money. What writers wrote was put on the screen, mostly without rewrites. That's why the pictures had unity and why many survived the time.

It was very satisfying work, knowing that our screenplays would not be messed up. I remember working for George Waggner, who passed away last

Curt Siodmak at his writing desk, 1950. (Courtesy of Curt Siodmak)

year; I made eight pictures for him, yet I could never talk to him. He'd say, "I don't want my idea. I want your ideas. . . ." I guess my pictures have a kind of bridge and roundness to them. You don't find in them other ideas coming from someone else, which don't belong.

For the most part, though, you were just concerned with making a living .

I had an invisible altar in my office at the studio. When I couldn't take it

any longer, all that crap, I went to it, in my mind, and said, "My weekly check! My weekly check!" Then I continued working. It wasn't more than a job. One year I wrote seven different screenplays, because you have to live, and I was in demand.

How did the system work for you, exactly?

There's this producer, right, who's pulling down $10,000 a week. He doesn't want to make a picture, because he might fall and break his neck. But after he got paid half a million dollars, what can he do? He has to make a picture, only he doesn't know which one. So the agents come in, with their lists of writers. They have all these prices—$500, $750, $1,000, $2,000, $3,000 a week. The producer looks at the writers available, and let's say he comes across my name and he knows that I haves track record. He says to himself, "Maybe Siodmak might know what I want, so I don't fall flat on my face."

So I come in and meet a man I've never seen in my life. I have twenty minutes with him where he tells me the idea for the film he would like to make. I have to convince him that this is the best idea that a man could ever have; it will make a zillion dollars. You have to be convincing, because he is watching you. The slightest doubt he will see in your eyes—just as if you're talking to a girl you want to make. If she sees any doubt in your eyes, you're out of the game. Then the producer says to himself. "Siodmak is so convinced, my idea must be good." We shake hands. I have a job. I go to work right away, get my weekly check. This is how you got your job. You had to know how to sell yourself. . . .

What screenwriters did you admire in Hollywood?

The Epstein brothers [Julius and Philip] were marvelous comedy writers, and Budd Schulberg . . . There are many. Hollywood had very independent writers. Every one did his special job and there wasn't much personal contact between the different writers inasmuch as we worked mostly on assignment and were not under contract. I never was. Though I had written a number of musicals for Susie Forster and Ginnie Sims, I fell into the groove of writing "horror" films which actually were gothic stories. But I could write on any kind of subject. . . .

Making pictures is not a one-man job. It's a collaboration of a group of people. I think a cutter does at least as much constructive work as a director, or the actors. Writing is only a part of the motion picture machine. But without the writer . . .

Filmmaking is a cold-blooded business. I don't know why there should suddenly be such a tremendous interest in the pictures we made in the forties and fifties, of which I'm part.

What films would you like to be remembered for, as a screenwriter?

Well, look, I didn't make big pictures in America, not the blockbuster. I made mostly B pictures, accompanying pictures for the big show. Strangely, some small pictures that we wrote survived the expensive ones. It is the idea

of the story and the precision of the screenplay which make a film survive the decades, not the money which is spent on it. And I have written a few pictures which have been shown for the last forty years. So we never know what we do, eh?

While Siodmak is not currently active in Hollywood, he continues to write and publish. His novel I, Gabriel was recently published in Germany, where many of his early novels have come back into print. Also, he's written an opera, Song of Frankenstein, and a play about Jack the Ripper, and is finishing his new play about three important days in his life that will incorporate one of his best works: "Epistles to the Germans," a series of letters he exchanged with former German friends after World War II, looking into the reasons for the Nazi movement and how and why Germans collaborated with it. He is working now on a television miniseries for Europe, adapted from his novel For Kings Only, which was published nearly thirty years ago in America. He believes that every story has its time. All you have to do is wait .