Chapter III—

Municipal and Royal Building up to 1559

François I encouraged the building of and contributed money for the new Hôtel de Ville as a practical gesture of his interest and need for a closer relationship with the richest city of his kingdom. The Hôtel de Ville was the most prominent of the municipality's building projects, but the échevins were responsible for two interesting developments in town planning leading to and on the Ile de la Cité, the terraced houses on the new Pont Notre-Dame of c. 1508 to 1512, and a row of houses which stood between the Petit Pont and the Hôtel Dieu of 1552–1554 (Figs 50–52). Their patronage of the arts in general remains to be studied, but as paymasters for the official royal entries, with their temporary architectural set-pieces of triumphal arches, fountains and perspectives, they provided occasions and opportunities for stylistic innovations from the leading architects and sculptors.

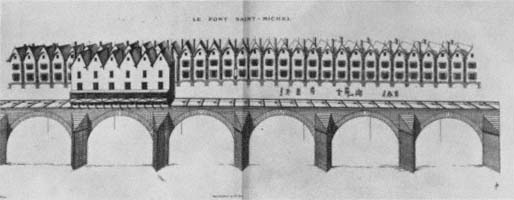

The history of urbanism in Paris conventionally begins with the initiatives of Henri IV during the first decade of the seventeenth century, the building of the place des Vosges begun in 1605, the completion of the Pont Neuf with the triangular place Dauphine at its middle on the western end of the Ile de la Cité and the opening of the rue Dauphine from the south of the bridge, as well as the projected semicircular place de France with its radiating streets in the north-east of the city planned in 1610 but abandoned with the assassination of the King in that year.[1] Henri IV and his minister Sully had a keen interest in improving key vacant portions of the city with terraced houses for upper bourgeois and aristocratic pockets, built efficiently and economically in brick and stone. The example of the cities of Flanders was studied for the organization of publicly-funded urban projects and persuaded the King and his minister of the advantages of brick over the traditional range of stone used in Paris.[2] A hundred years earlier the same considerations faced the council having almost completed the costly replacement of the Pont Notre-Dame, and as finished in 1512 the road over the bridge was flanked by two terraces of gabled houses built of brick and stone at the front, but with cheaper timber framed backs[3] (Figs 50–51). The thirty-four houses in each row consisted of a cellar, a shop with a narrow stair passage at the right leading up to two floors of accommodation one room wide, and an attic under the gable. The luxury trades like shops on main thoroughfares, and the municipality's speculative building on the Pont Notre-Dame attracted good rents from goldsmiths

51

The Pont Notre-Dame, described as the Pont Saint Michel. Engraving by Androuet du Cerceau.

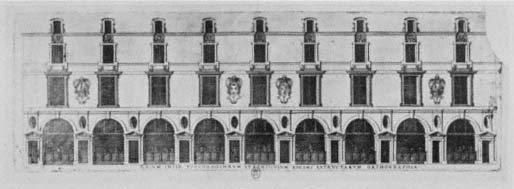

52

Terrace between the Petit Pont and the Hôtel Dieu on the south side

of the Ile de la Cité. Engraving by Androuet du Cerceau.

and hat makers, and the best known representation of one of these shops on the Pont Notre-Dame is Watteau's painting of Gersaint's The Picture Dealer , with its fashionable clientele as much on view to the passerby as the paintings. In early sixteenth-century Paris this type of tall, narrow house was common on the main arteries, but it was the uniformity of the houses on the Pont Notre-Dame which excited contemporaries' admiration,[4] and this uniformity was protected by the council who forbade any alterations by tenants. The lightness of the houses' structures was in part influenced by the need not to make the bridge unstable with a heavy superstructure but, equally important, was economy and the speed of building.

Single-bay terraced houses with an arcade of shops was the formula for the only other municipal speculative development whose appearance is

known from one rare engraving (Fig. 52). The builder was the city's master mason, Guillaume Guillain, whose design was vetted carefully or casually by a panel of experts, which included the designer of the Louvre, Pierre Lescot, in 1552.[5] As with the terraces of the Pont Notre-Dame, the two floors of apartments were reached by a passage and stairs to the side of the shop. The principal structural difference is the change from roof gables to a continuous pitched roof. The bond of monarch with his capital is celebrated by the pairs of royal arms in the centre with those of the City of Paris over to the left and right, and to please Henri II further are the emblems of Diana, the bows and crescents over the second-floor windows in tribute to his mistress Diane de Poitiers. The only truly classical features were in the ground-floor arcade with its pillars, block capitals, key stones, oval oculii and triangular pediments over the doors. Above, the windows of the two main floors have mouldings with ears or lugs breaking out at the top sides, which are simplifications of those designed by Lescot for the ground floor of the Louvre. It was natural for a body whose roots were in the merchant guilds to build economical and practical premises for trades, rather than involve itself in residential developments of the more prestigious and risky kind. Their obligations in the sphere of building were with building and maintaining bridges and quaysides, the maintenance and improvement of roads and fountains, the enforcement of building standards and by-laws, rather than with any truly urbanistic notions of the architectural renovation of a quarter of the city as a whole.

The early history of the new Hôtel de Ville is incomplete, especially the circumstances and conditions under which this curious building was designed. In comparison with the cities of Flanders and northern France or the major towns on the Loire, the municipality of Paris had no inspiring institutional building, and as a direct result of the royal declaration of 1528 the échevins felt obliged to build premises appropriate for civic and for national occasions. At a meeting on the 29 November 1529 the 'Bureau de la Ville' told the Governor of Paris of their intention to build, and the King promptly assured them of funds.[6]

Designed in 1530 or 1531 by the King's nominee Domenico da Cortona nicknamed the 'Boccador', an Italian long established in France,[7] and executed by the city's master mason Pierre Chambiges,[8] the Hôtel de Ville looks like no Italian building but in its decorative details was the most important Italianate or classical building in the capital before it was eclipsed by the new Louvre. Even with the acquisition of more houses to enlarge the site the planning of the Hôtel de Ville proved awkward, the front facing the place de Grève was the longest side of an irregular trapezoidal courtyard building (Fig. 53). The archway on the right gave access to the rue du Martroi, and to make the façade symmetrical a pair to it was built on the left side which screened the chapel of the Hôpital du Saint Esprit much to the chagrin of the masters and governor of the hospital.[9] Attached Corinthian columns articulated the ground-floor arcade and their tall podia

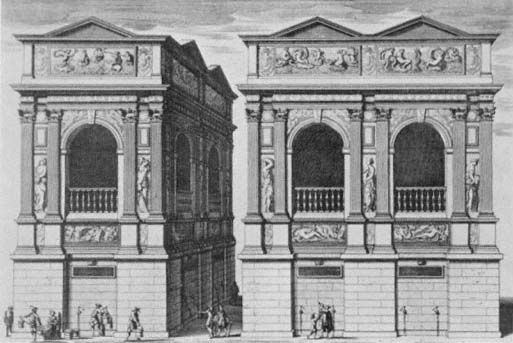

53

The Hôtel de Ville. Engraving by Israel Sylvestre.

on a blank frieze defined the height of a high basement. Between the two large archways, the ground-floor arcade with its recessed pedimented windows is a revision of the elegant tiers of open arcades of François I's Château de Madrid in the Bois de Boulogne begun in 1528. Correctly, no order stands above the Corinthian of the ground floors, and niches with statues filled the spaces of the main floor, but this may not have been the first architect's intention for the central section of the main floor and the left-hand pavilion above the archway were only completed under Henri IV. The Hôtel de Ville is an intriguing mixture of imported decorative features applied to a building wholly French in form. The silhouette with tall pitched roofs on the three-storey north and south pavilions and the separate pitched roof for the lower main body of the building is a hallmark of the François I style. During the late seventeenth century, when fashion had roofs lowered behind balustrades to make an uninterruped skyline, the new kind of roof was called a 'combe à l'italien'. There is little evidence from sixteenth-century France of new classical decorative styles developing into an interest in all aspects of ancient and contemporary Italian building practice. Indeed, the circumstantial evidence and French architectural pattern books point to a qualified interest in Italian building, where the specialized and virtuoso skills of Parisian master masons and carpenters, in features such as suspended angle turrets and pitched roofs, retained their place in the design of a prestigious building.[10] The two-storey projecting turrets of the Hôtel de Ville, with their springings decorated with layers of motifs adapted from the mouldings of a classical pediment, are proof of the continuity of a building tradition unaffected by

54

The Fontaine des Innocents. Engraving by Perelle.

a change in decorative taste. After several interruptions, work stopped on the Hôtel de Ville in 1551, the year in which Pierre Lescot concluded the second and definitive contract for the new Louvre. Lescot was the architect of the Fontaine des Innocents, the most opulent sixteenth-century Parisian water source.

Built on a corner of the rue Saint-Denis the traditional route for royal entries, the Fontaine des Innocents (Fig. 54) was almost complete at the time of Henri II's entry in June 1549.[11] In its present rebuilt state, it is the only vestige of a state entry from the ancien régime whose set pieces were usually of wood and canvas, but it is characteristic of the council to make a royal tribute out of a public utility. The basement of the Fontaine des Innocents was the cistern, and its superstructure was wholly ornamental. The motif of the triumphal arch is used in a novel way in being repeated, with two on the long side on the rue aux Fers (now rue Berger) and one on the short side facing the rue Saint-Denis. Between the building of the Hôtel de Ville and the Fontaine des Innocents, illustrated architectural books of ancient and modern design had begun to appear, notably most of Serlio's libri amongst which he illustrated a selection of ancient triumphal arches inaccurately. In his designs of arcades and gateways, Serlio distinguished two contrasting manners, the 'rustic' or the bold and massive and the

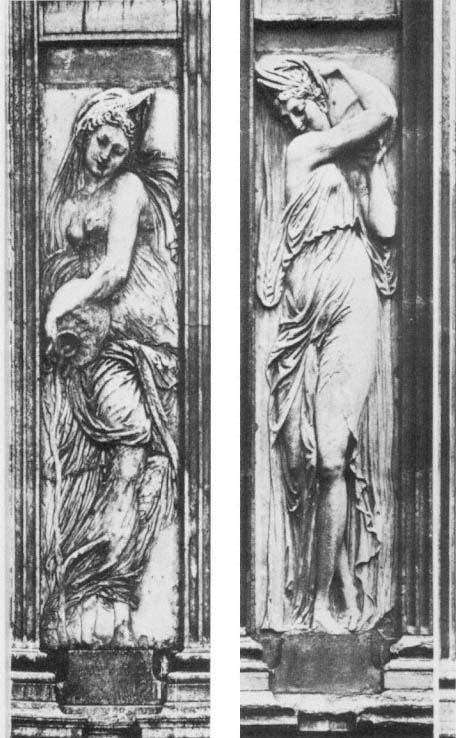

55

The Fontaine des Innocents. Reliefs by Jean Goujon.

'delicate'.[12] Lescot's arch compositions are elaborate and elegant revisions of the arches he saw in Serlio, with fluted pilasters instead of columns. The partnership of Pierre Lescot with the sculptor Jean Goujon will be described in more detail at the Louvre, but the close incorporation of architectural members with shallow relief sculpture (Fig. 55) guided Lescot towards a composition of fine line which would work well as a framework and a foil for the sculpture. The open loggia was one of the choice viewpoints for the processions of royal entries where a select group of ladies and gentlemen greeted the King. In July 1665 Bernini commented that in his opinion the Fontaine des Innocents was the most beautiful building in Paris,[13] and it is strange that his admiration did not extend to the architecture or sculpture of the Louvre.

As was to be expected, contemporary writing about Lescot and his design of the Louvre are laudatory to the point of being wholly uncritical. The lavish praise of Ronsard's Elegie à Pierre Lescot usually finds a place in anthologies of sixteenth-century French verse, and Jacques Androuet du Cerceau properly put the Louvre at the beginning of his two volumes of Les plus excellents Bastiments de France in 1576. Only the antiquarian and polymath Blaise de Vigenère felt Lescot's Louvre was too full of mistakes to please the trained eye. During the 1580s he wrote

Feu Monsieur de Clagny (Pierre Lescot) envers nous, lequel ne s'estant jamais exercé qu'au crayon, plustost encore d'un instinct naturel propre en luy et incliné à la pourtraicture (drawing) que par art acquise, a neantmois conduit assez heureusement le Louvre de fonds en comble tel qu'on le void, combien que ceux qui sont versez en l'art y remarquent tout plein d'erreurs tant par dedans que par dehors. A la vérité ces grands pièces méritent bien de passer par les mains de ceux qui ont fait leur apprentissage et coups d'essais en d'autres moindres suyvant le dire commun Italien 'gastando s'impara', qu'un tailleur avant que se randre bon maistre aura gasté assez de drap . . .[14]

Unfortunately de Vigenère leaves us to guess the faults in this unconventional and thoroughly original building (Figs 59–63).

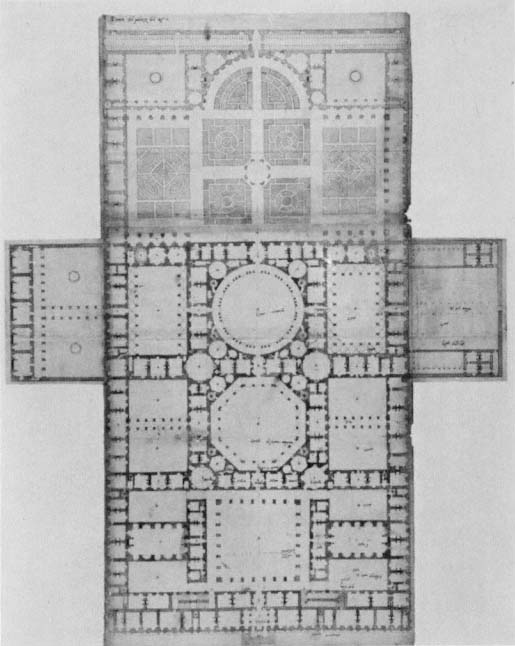

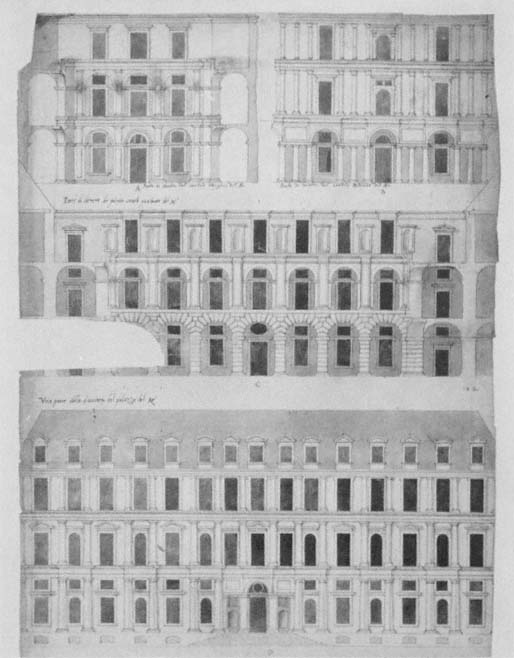

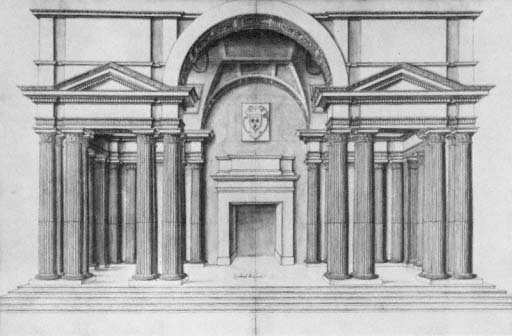

Serlio's proposals for a city palace for the King were rejected by 1546 when Lescot was appointed architect of the Louvre by François I (Figs 56–58). The scheme devised by Serlio in its massive scale took none of the topographical conditions of the western end of the city into account, and would have required drastic clearances in a populous quarter. The elevations of this forlorn project are the most developed and subtle of Serlio's blends of Italian and French building practice and architectural styles. The windows are of French proportions and the lofty pitched roof would have required the special carpentry techniques which Serlio met in France. The limited use of the orders to articulate key portions and give balance to the extensive elevation is a method of classicizing untried in

56

Sebastiano Serlio. Plan of a City palace for the King. (Avery ms. n° LXII)

57

Sebastiano Serlio. Elevations for the City palace for the King. (Avery ms. n° LXXII)

58

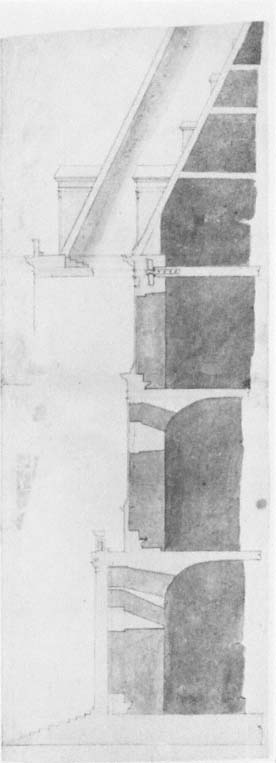

Sebastiano Serlio. Section of an elevation

of the City palace project. (Avery ms. n° LXXIIIa)

59

The Louvre. Plans of the ground and first floors.

Engraving from Le Premier Volume des plus excellents Bastiments de France by Androuet du Cerceau of 1576.

France where the previous and contemporary style was for continuous friezes with pilasters in each bay.[15] The literate proportions of the sparingly used orders gives Serlio's project its pseudo-Italian appearance, for the masses are unlike any Roman or Venetian palace. The wall section (Fig. 58) shows a further refinement by Serlio to give relief to his façade design, which is not apparent from his elevation drawing. By staggering the advance of each of the floors, Serlio showed the Court one way of further animating a monotonous wall, and this idea was pilfered by Pierre Lescot. Lescot was a personality whose qualities of mind were of more interest to François I, than an aged Italian architectural popularizer who did not express himself in French.

According to a Venetian ambassador, François I had the ability to discourse pertinently on all of the arts. The nickname of his nominee for the design of the Hôtel de Ville, the 'Boccador', is just one reference to the qualities of eloquence and erudition which we know could impress François I in a servant or courtier. Blaise de Vigenère's characterization of Lescot as a talented draughtsman, with perhaps a sound theoretical grasp of principles of architectural style, but with no practical or technical expertise, would help to explain the partnership of a royal favourite with broad artistic talents[16] with Jean Goujon. Jean Martin's translation of Vitruvius, published in 1547, has woodcut illustrations made by Goujon which required the sculptor's own reading and interpretation of the text. The hellenism of some of Goujon's bas-reliefs complements contemporary

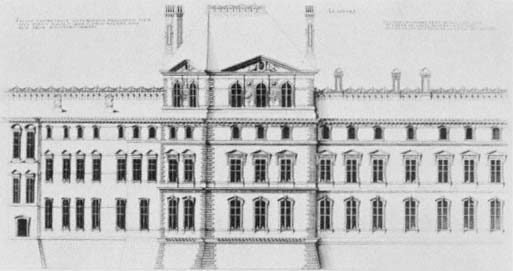

60

The Louvre. Elevations of the west and south fronts with the pavillon du roi .

Engraving from Le Premier Volume des plus excellents Bastiments de France

by Androuet du Cerceau of 1576.

developments in theatre and literature at Court[17] and shows Goujon, if proof were needed, to have been both practician and connoisseur of ancient art, a distinguished junior partner to Lescot.

The chronology of the building of the Louvre under Lescot has been clearly established from archival sources, but one important document has been lost, the contract for a more limited house which Lescot presented to François I in the year before the King's death in 1547.[18] Henri II wanted the programme expanded and masonry contracts from 1551 and 1556 with agreements between Lescot and Goujon for the sculpture have survived.[19] The initial project of 1546 is thought to have been for a square courtyarded house, not much bigger and following the lines of the medieval Louvre and it was François I who ordered the demolition of the keep in the middle of the courtyard and of the west and south wings.[20] Only the west wing and the 'pavillon du roi' were built before Lescot's death in 1578, but the south wing was completed almost exactly according to Lescot's intentions by his assistant and successor in charge of the Louvre from 1582, the engraver du Cerceau's eldest son, Baptiste.

Jacques Androuet du Cerceau's engraving of the outer west and south fronts with the 'pavillon du roi' in the middle (Fig. 60) is the best record of these façades, which were austere in contrast to the densely ornamented courtyard elevations (Figs 63–65). Cost would have been one reason against cladding both sides of the Louvre with relief sculpture and pilasters,

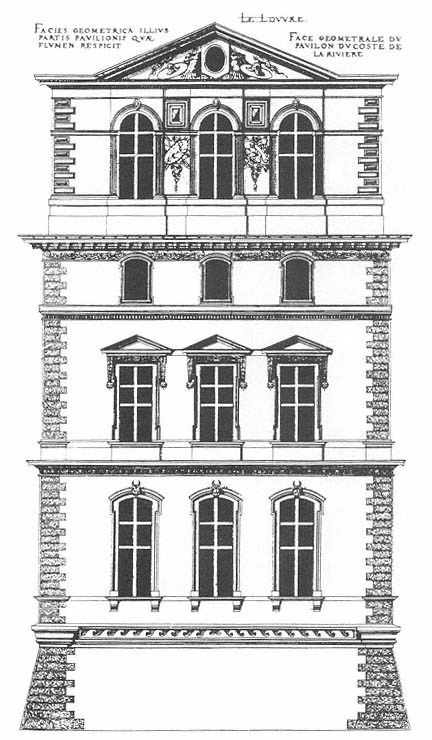

61

The Louvre. South elevation of the pavillon du roi .

Engraving from Le Premier Volume des plus

excellents Bastiments de France of 1576.

62

The Louvre. West front about 1660. Engraving by Israel Sylvestre.

but there must have been a further scruple in Lescot's mind suggested by Serlio, who had written that the public face of a gentleman or lord's house should not be so rich or ostentatious as to provoke jealousy or contempt. Hierarchical notions or architectural decorum pervade Serlio's writings on architecture and, in simplistic terms, the architect was urged to devise a style appropriate to each commission, for the town or the country, for the class of the patron and the function of the structure. The repertoire of classical ornament, as enlarged for his northern European readers who had never seen Italy, made masons and amateur architects aware of new expressive possibilities in wall decoration; in our discussion of late sixteenth-century aristocratic hôtels we shall see the currency of ideas where the use of the most intricate and pretentious classical ornament was viewed as suitable only on the buildings of the most noble.

The outer face of Lescot's west wing, on the left of the Pavillon du Roi in du Cerceau's engraving (Fig. 60), was plainer than the south front executed later by Baptiste Androuet du Cerceau,[21] to make the grand angle with the Royal apartments the more imposing and prominent, and the contrast with the courtyard façade the more dramatic. The decoration of the Pavillon du Roi was calculated to be legible from the other side of the river, with bold rusticated quoins and broad blank friezes dividing the floors underlined by narrow classical cornices. The large chamber which crowned the structure was an imposing belvedere with clear views over the countryside of the Left Bank and west along the river to Chaillot. The use to which this chamber was put is not known and it may never have been decorated inside. As shown by Androuet du Cerceau (Fig. 61), the Pavillon du Roi

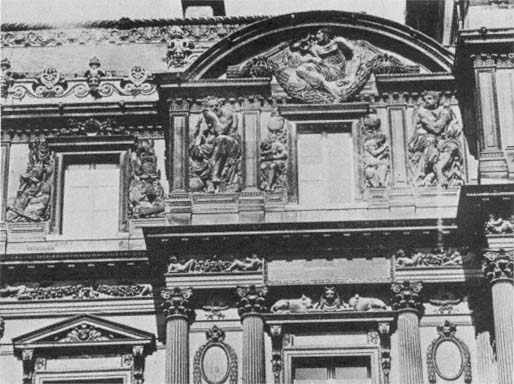

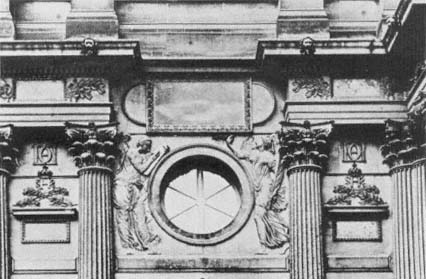

63

The Louvre.

might be thought to have looked top heavy. The Louvre garden was a small space between the Pavillon du Roi and the river, whose greatest width was the length of the Petite Galerie (Fig. 62). Goujon made a woodcut for Martin's edition of Vitruvius to illustrate Vitruvius' point that statues on the pediment of a temple on a narrow street should be taller than normal to be seen properly at the imposed acute angle. Seen near to and below from the garden by the King or the Court, the proportions of the crown of the Pavillon du Roi should have looked satisfactory.

Possible relationships of Lescot's Louvre with the styles of the Renaissance architecture in other countries have never provided an insight into Lescot's architectural background or thought. There are no respectable sources either for the composition as a whole, or evident quotations by Lescot in any of his combinations of decorative detail on the courtyard front (Fig. 63). A project as much en vue as the new Louvre at the time of its design and building was likely to be heterogeneous from a designer devising and refining his ideas on the drawing board, and with advice on points of iconographical and possibly architectural details being proffered by men at the artistic heart of the Court like Ronsard.[22]

The elevation is nine bays wide, and in height has a ground and first floor of equal height, with an attic of half the height of the two main floors. The court front has subtle overall relief with the ground floor and the three

pedimented frontispieces slightly projecting from the alignment of the rest of the first floor and attic. These gradations were not over emphasized by Lescot, for with even or weak light or with direct sunlight on the façade, these volumes are indistinct. The main horizontals of the design are the friezes and cornices above the ground and first floors; the ground-floor frieze and cornice is broken in the central bay of the three frontispieces which creates a more distinctive vertical accent for these advances. The idea of the shallow ground-floor arcade might have come to Lescot from the less refined Hôtel de Ville, but the slight recessions in the first floor and attic must have been adapted by Lescot from Serlio's project.

The distinctive use of the orders on Lescot's Louvre has been the object of much comment because of his use of the two most decorative of the orders, the Corinthian for the ground floor and the Composite on the first floor. A ground floor of a contemporary Italian palace would have the Doric on the ground floor with the Ionic for the first floor, obediently following the vertical sequence of the orders set by the Colosseum and repeated by architectural writers of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.[23] Lescot knew the true classical prescription for the orders on a tall elevation, but ignored it for at least two reasons. Firstly, the Corinthian and Composite used together produced decorative consistency in the make up of their capitals, and secondly they were thought of as the most evolved of the classical orders. Single pilasters divide the bays, with paired columns used to give greater relief on the frontispieces, where on the ground floor are doorways; that on the right-hand side leads into the double ramp of the Henri II staircase (Figs 59 & 56) and the other two would be opened for grand ceremonial occasions held in the Salle des Caryatides on the ground floor (Figs 59, 67-68).[24] The result of the use of columns on the frontispiece is to give the entrance bays an appropriate architecture of two tiers of triumphal arches.

Pierre Lescot never devoted himself entirely to architecture, and the number of commissions he is known to have accepted is fewer than six,[25] but the greatest loss is his copiously illustrated architectural treatise which on his death was inherited by his nephews, and which contemporaries hoped would be published, but the manuscript has disappeared without trace.[26] His book should have shown his knowledge and practice of a broader range of styles than the elegant or 'delicate' manner which he developed for his partnership with Jean Goujon, and to accommodate and complement Goujon's relief sculpture. The only evidence of his range is the Château de Valléry, designed by Lescot for one of Henri II's favourites the Maréchal de Saint-André, which in form has many similarities to the Louvre, but there Lescot used a rusticated decorative idiom with few classical motifs, a style appropriate for the country seat of a military leader.[27]

The sources, style and iconography of the sculpture on and in the Lescot wing of the Louvre have been discussed at length by historians and art

64

The Louvre.

65

The Louvre.

historians.[28] The allegorical figurative reliefs on the courtyard façade have been described as 'a paean of praise to monarchical government, its pretensions, prerogatives and obligations as well as the blessings it assures'.[29] The achievements conveyed by the figures in the attic are Abundance in the south pediment personified by Neptune and Ceres underneath, Victories with the royal escutcheon fill the central pediment with Mars and Bellona flanked by captives underneath, and Science in the north pediment celebrates the intellectual prowess of the French personified by Archimedes and Euclid accompanied with a Genius reading and a Genius writing (Fig. 64). Most of the attic figures are loosely based on the ignudi in Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling. A number of minds may have contributed to devising the overall iconographical scheme and to the selection of attributes, but Lescot's role was primordial in all matters of the design.

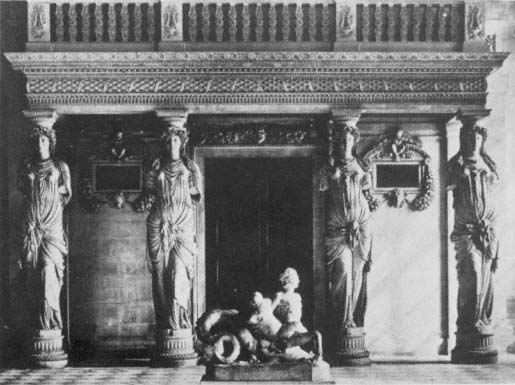

The caryatid portico at the north end of the Salle des Caryatides on the ground floor is usually labelled as by Jean Goujon in general histories of art (Fig. 67). The agreement for these sculptures made on 5 September 1550 between Lescot and Goujon is enlightening on its design and purpose.[30] The Salle des Caryatides is described as 'la grande salle de bal', and the balcony of the portico was to be a minstrel's gallery for oboeists and other kinds of musician; the sculptor should have been competent to design a caryatid portico symbolic of victory, but the text specifies that Lescot had passed on a plaster model for Goujon to follow. Illustrated editions of Vitruvius usually showed their editor's idea of the appearance of the antique caryatid portico described by Vitruvius,[31] and Goujon's woodcuts for Martin's edition of 1547 arguably are the finest of all the sixteenth-century versions of the subject, but Lescot introduced significant modifications and corrections in his design passed to Goujon in 1550.[32] The Louvre's caryatid portico was the first time a passage from Vitruvius had been used to recreate an antique monument on the monumental scale and in a permanent form.

At the opposite end of the ball room from the caryatid portico was the 'Tribunal' (Fig. 68) and dais, with a curious architectural superstructure whose purpose is unknown, but which would have made an imposing setting for an entrance by the monarch from the state apartments behind, through one of the doors on either side of the fireplace in the middle. The architecture of this set piece was of two sets of groups of four fluted Doric columns on either side of a vaulted arch. A source for the composition which has been suggested is Giulio Romano's portico on the garden side of the Palazzo del Tè at Mantua,[33] but here the context is very different, and until the use of this ensemble is discovered, the iconography of this distinctive piece of architecture must be left to speculation.

The Louvre's main staircase, built from 1551 onwards behind the caryatid portico at the north end of the Lescot wing, cannot have been Henri II's Queen Catherine de Medici's favourite way of climbing to the

66

The Louvre. Vault of the Henri II staircase.

67(a)

The Louvre. Caryatids portico. Drawing by Androuet du Cerceau.

67(b)

The Louvre. Caryatids portico. Present remodelled condition.

68

The Louvre. Tribunal. Drawing by Androuet du Cerceau.

first floor. The compartments of the vaults were filled with emblems of pleasure and the hunt, fauns, Pans and dogs, but worst from her point of view was the blatant celebration of the King's mistress with the goddess Diana (Fig. 66). The only other glories of the inside of Henri II's Louvre to survive are two wood coffered ceilings from the King's 'chambre de parade' and the 'antichambre du roi' from the Pavillon du Roi[34] (Figs 69–70). The carving of the former was by the Italian Scibec da Carpi, but once again a contract of 1556 shows the design was by Pierre Lescot.[35] The outside cornice of consoles and garlands, the pairs of square coffers close to the corners of the outer zone and the central rectangular frieze decorated with laurel leaves are quotations or derivations from antique architecture used in a new context. The delicately carved friezes of the coffers are more correctly Roman than anything seen in France before, even amongst Scibec da Carpi's previous work for the Crown at Fontainebleau, and has few equivalents in Italy. The largest of the suits of armour, shields and other trophies were separately carved, and the whole ceiling was assembled in such a way that it could be dismantled for cleaning.[36] In the reign of Charles X it was removed from its original location to the third chamber behind the colonnade of the east front. The ceiling of the 'chambre de parade' was entirely gilded, and one day its brilliance might be restored. That of the 'antichambre du roi' also has suffered and now has wholly

69

The Louvre. Ceiling of the chambre de parade du roi .

unsuitable paintings by Georges Braque in lurid blue and white fitted in its panels. The carving was probably by Jean Goujon with Etienne Cramoy, and the design should be attributed to Pierre Lescot.

It is easier to describe the Louvre than to attempt an analysis of its style. The courtyard façade is the most sumptuous and dense display of columns and pilasters with figurative and architectural sculpture on any palace of the age, but it is not as richly festooned as Lescot intended for the blank frieze at the bottom of the first floor was to have carving.[37] Blaise de Vigenère had heard criticisms of Lescot's Louvre, and it is his characterization of

70

The Louvre. Ceiling of the antichambre du roi .

Lescot as a man more versed in drawing than the rules and techniques of classical architecture and of building, which points to Philibert de l'Orme as the anonymous objector.

De l'Orme was the architect of all the royal building projects under Henri II except the Louvre, where François I's choice of designer was respected by his son. The nine books of de l'Orme's Architecture published in 1567 is a remarkable compendium of practical building and stylistic advice based on his own experience and illustrating houses designed by himself. His text is full of calls to patrons to employ a man like himself, who had a first-hand knowledge of antiquity, of mathematics, and architectural theories, and above all with a sound knowledge of building materials and conditions in France, and for patrons not to be impressed by or employ 'faisseurs de desseins'.[38] The tenth chapter of his first book is a tirade against 'parrots' who may speak well and draw nicely, but whose presumption in calling themselves architects infuriated de l'Orme. Pierre Lescot was not the only courtier known to have taken a special interest in architecture; one of the Pléiade Etienne Jodelle, the poet and dramatist who introduced a pure form of Greek tragedy into the French theatre, listed architecture as one of his accomplishments and is associated with the design of one of the most ostentatious country houses near to Paris during the late 1550s.[39] In de l'Orme's mind, an overlay, richness or massing of ornament was a trait of the imposter who could not provide a rational basis for his design. He must have been contemptuous of Lescot before all others, but his book only describes his views on how things should be done and he avoids offending the Royal family by razing the Louvre with his thinking on architectural reason. De Vigenère refers to faults both on the inside and on the outside detected by 'ceux qui sont versez en l'art'. De l'Orme would have objected to the use of a caryatid portico as a minstrel's gallery in the ball room, for the one erected by the Greeks had been a public monument of triumph in the open air and set nobly on a podium. For Anet about 1548 de l'Orme designed a frontispiece for the centre of the main block, which might be seen as his corrective to Lescot's on the Louvre. De l'Orme opted for a correct sequence of columns one above the other, the Doric below, with Ionic and Corinthian above, and each given appropriate relative proportions, the Doric being the shortest and the Corinthian at the top the tallest. Crowning a frontispiece of columns with weaker half pilasters must have been viewed disfavourably by de l'Orme in Lescot's design. Other solecisms at the Louvre which can be sifted are so inconspicuous that Lescot ought not to be remembered as a gentleman or amateur architect, with such a label's connotations. In its originality, Lescot's Louvre is a work of architecture which perfectly reflects the aspirations of contemporary poets for a great national revival of literature inspired by but not beholden to the precedents of antiquity.

The death of Henri II in 1559, after a jousting accident, led to the temporary disgrace of Philibert de l'Orme, marks the effective end of

Pierre Lescot's interest and activity in architecture and placed the King's widow, Catherine de Medici, in power for the rest of her life, in a position to try to satisfy her extravagant tastes and considerable building ambitions. The reigns of her sons, François II, Charles IX and Henri III have been called aptly the Age of Catherine de Medici.