PART TWO

COSTUME MATERIALS AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE

All the Important ceremonies in the life of man are accompanied by manifestations in connection with dress. One of the fundamental characteristics of the human race is the desire to be dressed appropriately for an occasion. Man sets aside special ornamentation for his prayer and his drama. In order to appreciate his ceremonial costumes it is necessary to have a knowledge of his life and his habits.

The materials from which costumes are made vary with the geographical conditions under which a people live and with the degree of that people's cultural development. Among the Pueblos, articles of dress and ornament are the evolution of long experimentation in the manipulation of objects offered to them by nature, together with those which have been acquired through cultivation, invention, and trade.

Fabrication of Cloth

If the finished garment is to be appreciated fully, it is necessary to understand the method of fabrication which has made it possible, because its final appearance is based upon this and upon the materials used. We must remember that cloth fabric is a result of a series of operations which convert a mass of loose fibers into a woven material. The kind of fiber and the manner in which it is treated distinguish one cloth from another. Thus a cotton yarn and a woolen yarn of the same weight, though woven in a similar manner, do not result in fabrics which feel or hang alike. On

the other hand, the same cotton yarn may be woven by two different processes and produce fabrics which vary in body and surface texture.

Weaving done by hand is a result of plaiting or braiding three or more strands of material. This is the most primitive method, but alongside of it we find the free use of mechanical devices such as the loom.

"In the Southwest, braiding was known to the earliest people of whom we have gained sufficient knowledge to venture upon giving them a name—the Basketmakers. It therefore has some two thousand years of antiquity in this instance, for these people were flourishing and making attractive braided sashes ... as early as the time of Christ."[1] These can be traced through prehistoric Pueblo periods down to the present day in the plaited white cotton ceremonial sash so commonly used.

One other form of yarn manipulation is that of looping, a process which we recognize as knitting or crocheting. It depends upon a continuous series of interlocking loops which do not require a foundation and which proceed in a transverse direction with a single strand of yarn. Originally a finger process, it soon developed simple tools—the needles for knitting and the hook for crocheting. The development of these instruments marked a decided advance in technique. "Ancient peoples used needles of wood or bone"[2] to fashion garments from vegetable fibers and hair as well as from cotton and wool. Today the best examples of this art are the crocheted or knitted legging and footless stocking and the crocheted shirt. Although it is likely that these garments were introduced by the Spaniards, it seems probable that the looping process itself is older.

Fiber.

—Many different materials have been used in the process of weaving. Milkweed fiber has been employed, as well as small quantities of the hair of dog, mountain sheep, and bear, and even that of human beings.[3] Early in the Basketmaker era it was discovered that a fiber could

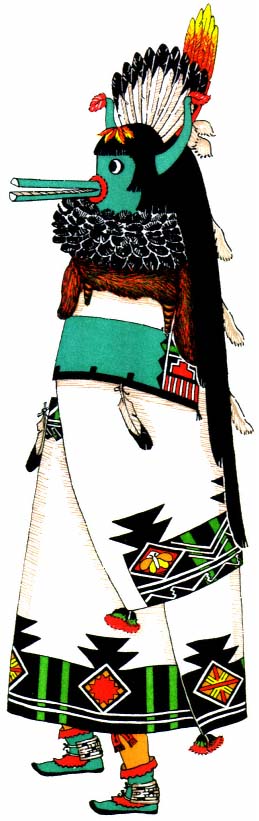

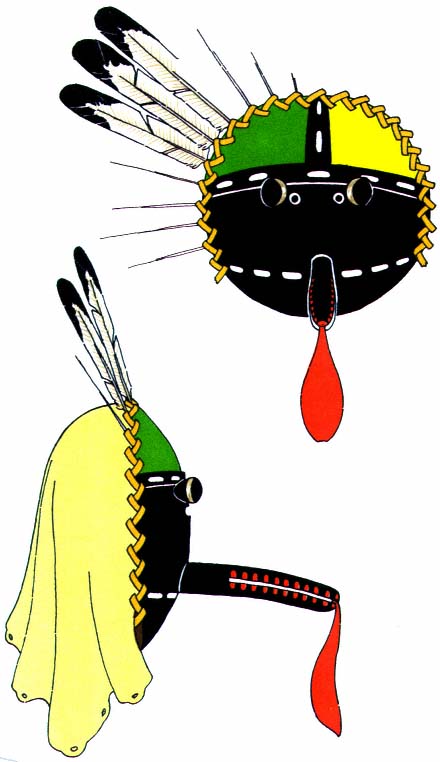

Plate 7.

Zuñi Shalako, one of six giant messengers of the gods. This ten-foot

effigy is balanced on a pole above the impersonator, who peeps

through an opening between the top of the ceremonial blanket,

used as a skirt, and the folds of the overlapping mantle.

be produced from the yucca plant. This "yucca fiber, alone or in combination with cotton, was of great importance as a weaving material. The fur of beaver, otter, or rabbit was incorporated with yucca cord or twisted around it to make warmer or more ornamental fabrics."[4] Even today the leaves of the yucca are softened by boiling with cedar ash, and when cool are drawn between the teeth in order to separate and cleanse the fibers. When soaking makes them pliable for use, they are rolled into rope or spun into a stiff thread for weaving.[5] Prehistoric remains have yielded us examples of bags, sandals, sashes, crude kilts, and clouts thus fashioned. Cedar bark was shredded and plaited and doubtless served the same purpose. Rabbitskins were cut while green into thin strips, and after drying and curing were woven into blankets and mats.

Materials so produced, however, were rough and clumsy: it was the use of cotton which introduced cloth and garments of an advanced kind. "Throughout the first four Pueblo periods cotton was the staple product from which cloth fabrics were made."[6] Cotton cloth has been unearthed in prehistoric ruins and burial places.[*] Cotton was grown wherever it could be cultivated, over almost the entire Southwest from the San Juan River on the north as far west as the Colorado and along the Rio Grande to the east.[7] In 1540 Coronado and his followers recorded its growth among the Tewa and its use at Zuñi[8] . By 1582 we learn from Espejo and Luzán[9] that it was in use among the Hopi, where, if we may judge by the great number and the beauty of the blankets displayed to them, weaving from cotton was undoubtedly a craft of long standing and high development.

About this time, also, feather mantles were in use. They were made by tying long eagle feathers in horizontal rows to a cotton base, in the process of weaving (pl. 2). The downy feathers of the eagle, the duck, and the turkey were twisted into the yarn in the process of spinning and this resulted in a cloth with a furry surface.[10]

* For example, on a body found in Cañada del Muerto, Arizona. The inner wrapping consists of two white cotton blankets, outside of which is a fine feather blanket bound by hanks of cotton yarn. Burial date, ca . 1000 A.D. Exhibit, Museum of Natural History, New York.

The Spaniards introduced sheep among the Pueblos, and thenceforth throughout their historic period woolen yarn and cloth played an important part; for all practical purposes woolen cloth replaced the former skin garments and the feather and cotton textiles. Cotton, however, has always been retained as a special ceremonial material, and it was always an article of luxury because of the small quantity which could be gathered within a single year and the tedious labor required to prepare it for use. Although it is not now grown, raw cotton and cotton batting are still sold to the Indians to be spun by hand into thread and woven by hand into cloth for certain sacred garments.

We are mainly concerned with the two fabrics, cotton and wool, which make up the principal woven articles of clothing.

Formerly this cotton (technically known as Gossypium Hopi Lewton), grew wild,[11] a small boll with a tawny fiber. Later it was cultivated.[12] "The cotton seed was planted in holes about one and a half inches deep and covered with white sand. The garden patches were divided into sections about a foot and a half square by little dirt borders to make watering easier."[13] The bolls were picked, broken open, and the fiber sorted, cleaned, and straightened by hand. This cotton was a distinct species with plants presenting ripened bolls within eighty-four days from the time the seeds were planted.[14]

Wool, after it was cut from the sheep, went through the same hand process of sorting, cleaning, and straightening, although it was often washed with suds made from the yucca root to remove all dirt and animal grease. With the coming of civilization the commercial wool card, a combing and straightening instrument, was introduced. This prepared the fibers of both cotton and wool[15] for spinning.

Spinning.

—The process of spinning produces a thread capable of being woven. The native spindle has a cylindrical wooden shaft about twenty inches long with one end rather sharply pointed. A whorl, or circular disk, of stone, bone, or wood is slipped over this shaft midway between

the center and the butt end. This acts as a flywheel and also serves to keep the yarn on the shaft. The spinner "takes one end of the roll of combed fleece in the left hand and holds it against the point of the spindle, rapidly revolved by the right hand, until it catches and twists spirally down the spindle shaft, the butt of which rests on the ground. As the loose roll twists around the spindle it reduces rapidly in size. The reduction is increased by drawing the thread away from the spindle with fairly

Figure 5.

Spindle, with yarn below disk. The disk is made of

born, bone, stone, or wood, with a shaft of wood.

hard jerks. When a section has been brought to a quite small diameter it is allowed to roll up on the spindle shaft, after which a fresh arm's length is drawn out for spinning. When the spindle is full the yarn is removed and rolled into a ball....

"The yarn produced by the first spinning is very coarse, lumpy and uneven, so that it has to be respun a number of times before it is fit for weaving. The finest and hardest yarn, used for warp, must be spun as many as six times."[16]

Good, hand-spun cotton produces a beautiful, coarse, irregular, creamy yarn. The woolen yarn is soft and lumpy. The differences in these yarns produce corresponding differences in the appearance and texture of the woven fabrics.

Weaving.

—Weaving is done on a hand loom of the two-barred type, which is set up in the kiva or in the house. In all probability this loom originated either in Peru or in Middle America,[17] and thence was introduced among the early Pueblos. It is always associated with cotton, and cotton is associated with corn in the most generally accepted theory of the New World origins of agriculture.

To prepare the warp a frame is made, consisting of two square side bars and two round end bars. The yarn is tied to one end bar, then strung from the ball in a series of figure 8's over the end bars until the required width of warp is obtained. These loops are called sheds. The side bars are then removed and the end bars replaced by loom strings, which are fastened to the loom poles by heavy cords wrapped spirally between the warps. A simple support is made by fastening a crossbar to the roof beam or to hooks in the wall. From this hangs the yarn beam, a small pole held in place by a rope wound spirally around the two. The tension of the warp can be adjusted by tightening or loosening this rope. The upper loom pole is now swung from the yarn beam by a series of loops, and the lower pole is fastened at the bottom to another beam, which in turn is secured to pegs in the floor or specially made sockets.

Figure 6.

Warp setup on end bars. Side bar l holds end bars k in position

so that warp m can be wrapped around them in figure-eight

loops. The first sketch, front view; second, side view.

For weaving, a shed rod is placed in the upper loop to retain the original order and to separate the lines of warp. Loosely tied to the front threads of the lower shed is a heddle rod, by which the alternate series of warp threads can be drawn forward, allowing a passageway for the shuttle or bobbin carrying the weft or filler which completes the fabric web. This passage is further opened by the use of a batten, a smooth,

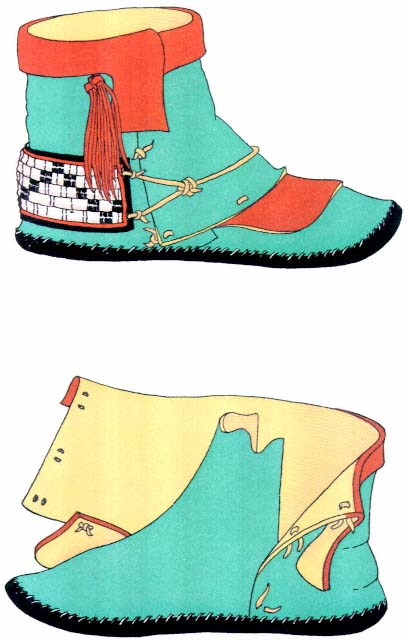

Plate 8.

Special two-piece dance moccasin. Heelpieces are

wound with white porcupine quills and black horsehair.

Figure 7.

End bars replaced by loom strings. Heavy cord n is twisted

between the warps m. Loom poles are tied to this twisted

cord by twine o. The end bars k are then removed.

Figure 8.

A two-barred loom. A dress is being woven.

Figure 9.

Diamond twill.

Figure 10.

Plain weave.

Figure 11.

Diagonal twill.

thin board with beveled edges, which is threaded between the warp and by a dexterous twist holds the shed open by its width. The weft is then beaten down with the same tool.[18] Self patterns and surface textures result from use of the different weaves and depend upon various heddle setups. A plain weave is the simplest and undoubtedly was the first ever to be

Figure 12.

Belt loom.

adapted to a loom. A simple 'over one, under one' formula produces a fabric in which each thread of weft intersects that of the warp on the same vertical line and both are equally visible.

A similar setup in which the weft becomes the dominant element and is pressed down so tightly that the warp is hidden is called a tapestry weave. This produces a firm, stiff fabric. Designs are effectively made by varying the number of warp threads behind which the weft is allowed to pass, a method called warp floating. This is done with the fingers, without the use of a heddle device. The designs are always limited by straight lines, which tend toward a constant repetition of a unit figure.

Pueblo examples of this technique are the belts, sashes, and garters. For these a smaller loom is required, which also differs slightly from that used for large fabrics. It is called a belt loom.[19]

A twilled basket weave is produced when each line of weft intersects the warp at constantly varying points, or when the regular alternation of the point of intersection produces ribs which trend diagonally across the face of the fabric. The width of the stitch may vary; but at least every other stitch must be two or more warp strands in breadth in order to provide for the alternation of the intersections in regular order. This makes the twill.[20] Two variations of this method are to be observed: a diamond twill, in the border of women's dresses, and the diagonal twill, often seen in maidens' shawls.

A brocade weave is used to decorate the ends of a special sash for men. This is made by the Hopi. The result simulates embroidery, but the method is weaving. It consists of a secondary or overlaid weft which is woven through the warp independent of the original weft. Color is introduced in this second thread, and by picking out certain warp threads with the fingers or by substituting another color simple designs are made. These are restricted, however, by the right-angled intersections of the loom setup.[21]

The Hopi of today is the Pueblo 'textile manufacturer'. He is the master craftsman and trader. From his villages on the three mesas overlooking the Painted Desert he carries on an extensive trade with the Zuñi and the Rio Grande Pueblos, who depend upon him almost entirely for their native textiles. In exchange for their turquoises, shell necklaces, and money he gives them dresses, robes, kilts, and belts, which they in turn "embellish with embroideries to their individual liking."

There is evidence that weaving was done in other pueblos. The Zuñi still produce some dresses, belts, and blankets.[22] It is known that loom weaving was practiced by the Acoma, the Santa Clara, the Nambé, and

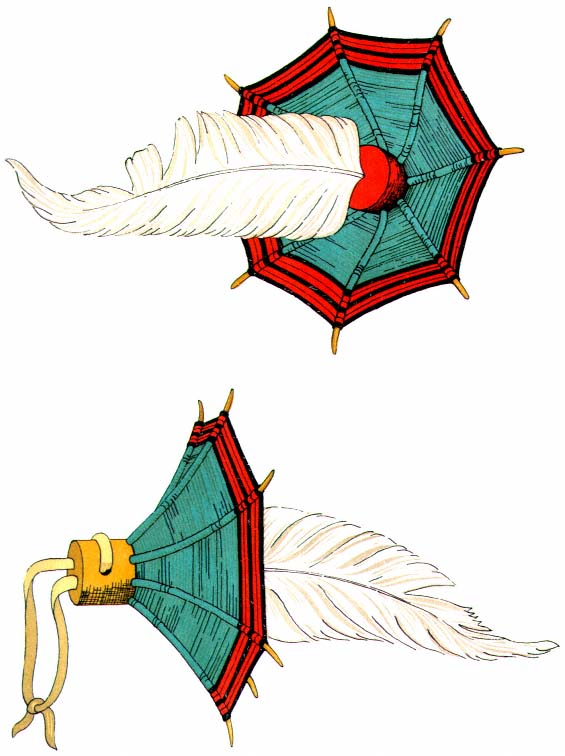

Plate 9.

Squash-blossom ornament used on headdresses and masks.

the Cochiti. However, these all depend upon Hopiland for those sacred garments which they carefully preserve for use on days of ceremony and entertainment.[23]

With very few exceptions men are the weavers[*] among the Pueblos.[24] They also make moccasins and the turquoise and silver jewelry, while the women make the pottery and weave the baskets.

Preparation of Skins

Tanned skins were useful for daily wear, and they supplemented cotton cloth, which, because of the time and labor required for its fabrication, could not have been produced in sufficient quantities. In the earliest Spanish records a follower of Coronado says of Zuñi: "The clothing of the Indians is of deerskin, very carefully tanned, and they also prepare some tanned cowhides [buffalo] with which they cover themselves, which are like shawls, and a great protection."[25]

The skins of wild animals are tanned and cured to make various garments and articles of ceremonial paraphernalia among the Pueblos. The material culture and the development of certain peoples are greatly influenced by the animals found in their districts. "The flesh ... furnishes food, the skins provide raiment, thongs and other useful products, and bones furnish awls and other implements; but perhaps even more important from the cultural point of view, is the fact that animals enter largely into the mythology and religion."[26]

We find not only the names of clans and individuals emerging from this association, but special parts of animals becoming symbolic in religious observances, such as the use of bears' paws in the rite of curing and the use of the headdress of the buffalo skin and horns in the Animal Dance. Animal horns were used on other headdresses and masks. Rattles were made of bones and hoofs. Horsehair, goat and bear skins, and wool were sometimes dyed and used as beards, wigs, and ceremonial trimmings.

* The rabbitskin blankets were always woven by the women.

Even the six directions bore the symbols of various animals. Thus the mountain lion represented the north; the bear, the west; the badger, the south; the wolf, the east; the shrew, the nadir; and the zenith was represented by the eagle.

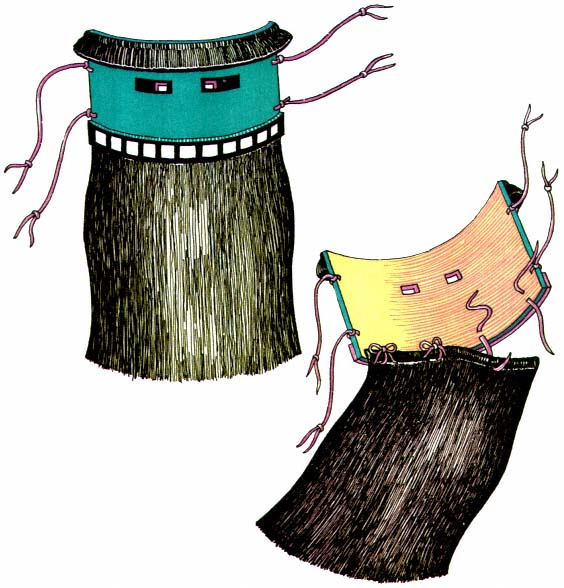

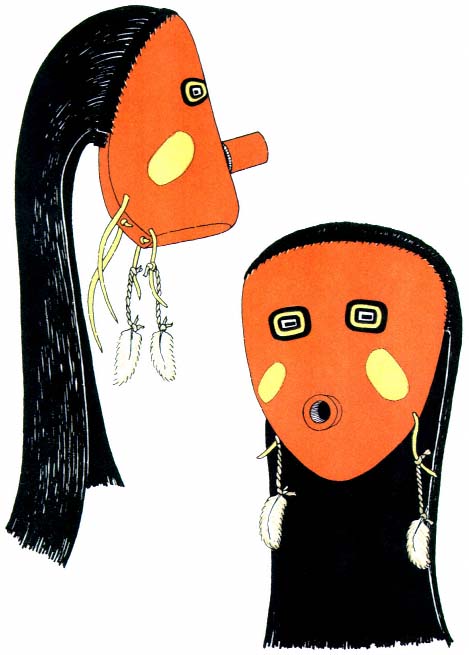

Furthermore, special qualities in certain leathers have produced a type of ceremonial apparel which could not have been realized had any other medium been employed. Helmet masks are fashioned from the heavy neckpieces of deerskin, buffalo hide, or present-day cowhide, while softtanned deerskin is made into kilts and mantles.

The variety of animals living on the arid plateaus of the Southwest was limited. The most familiar were probably antelope, coyote, and rabbit. Many legends center around the coyote, whose skin, it was believed, often concealed the metamorphosed body of some immortal creature. Rabbits were easily killed, and, since they were a prerequisite of the feast following the period of fasting and denial, they were hunted by large ceremonial groups, who encircled an allotted area, closed in on their prey and killed them with a throwing stick, a kind of boomerang which though curved did not return to its thrower.

Deer must have been plentiful, particularly in the winter when heavy snows in their high shelters forced them into the valleys in search of food.

Their beasts of prey were the bear, wildcat, mountain lion,[27] and fox. Of these the bear and the mountain lion were thought to be human beings who put on these skins at pleasure.[28] Great-horned mountain sheep were found in the high country on the south as well as in the Rocky Mountains on the north.[29] Likewise we are told of skunk,[30] squirrel,[31] porcupine, raccoon, badger, and otter. The former governor of Santa Clara wore summer ermine wrapped around his two braids when I called upon him at his home in the summer of 1936.

Through trade with other peoples the Pueblos were able to increase the quantity and variety of the skins which they used for their ceremonial and dress occasions.

Their neighbors to the east were Plains tribes whose existence centered in the herds of bison which roamed the prairie because it was mainly from these that they fed and clothed themselves. The need of a more varied diet sent these braves, who on other occasions were warlike, to barter their beautifully tanned leathers and pelts, preserved skulls, and bone beads for the delicious corn meal so painstakingly ground by the Pueblo women.[32] On the west, other seminomadic groups exchanged hides and pelts for the finely woven blankets, robes, and kilts of Hopi manufacture.[33]

As the Pueblos were a village people primarily concerned with agriculture, they depended for their food and clothing upon such crops as they could raise. They hunted only occasionally, in order to obtain skins for ceremonial needs and to procure the small amount of meat they needed to strengthen their vegetable diet. The hunt was a requirement prescribed by the War fraternity and directed by the warrior priests. To the Pueblo people all animals are living spirits and their right to exist is unquestioned. It is necessary, therefore, to pray to the animal and its family that it allow itself to be used for food and ceremony. After the kill, more rites must be observed, so that the spirit may not be displeased but may return to the other world and tell its kindred of the fine treatment accorded it.

The people of Taos and Picuris were descended from a Pueblo group who were tainted with the hunter's blood of the Apache and the Comanche. Living in close proximity to the plains, they had intermarried with the Plains Indians and had acquired habits resembling those of the aggressive, warlike marauders. They made long pilgrimages into the prairie country in search of bison.

Because they lived in the midst of wooded mountains, great herds of deer and elk came to the edge of their villages. It is not strange, therefore, that we find them much more influenced by their Plains brothers and eager to acquire the deerskin shirt and leggings, while their wives and daughters, Pueblo in their daily lives, sought to borrow the fringed

dresses for their festival occasions. Here, then, we find a fusion of two cultures in dress and in society and ceremony. In contrast, along the Rio Grande, at Zuñi, and among the Hopi were people, peaceful by nature, who bartered their corn and turquoises for skins which they made up after their own traditional patterns.

Since the surrounding tribes clothed themselves in skins and their methods of tanning were practically the same, the Pueblo men undoubtedly knew the technique of skin dressing and employed it in much the same manner as their neighbors.

Certain steps had to be followed in skinning an animal. There must be no waste. All the hide was retained. Sometimes the paws and hoofs were kept intact. This principle can be observed in the pendent foxskins worn at Zuñi or the head preserved on the fawnskin bag worn over the shoulder of the Zuñi fire god.[34]

A concise description of the manner in which skins were dressed by the Plains Indians is given by Frederic Douglas: "First the wet hide was staked out on the ground, hair side down, and the flesh, fat, coagulated blood, and fragments of tissue scraped off with a toothed gouge or fleshing tool of bone or iron. Second, the hair was removed and the skin reduced to a uniform thickness by scraping, each side being worked over in turn with an adze-like tool."[35]

The immersion for a few days in a lye bath of ashes and water to aid in the removal of the hair[36] is suggested by Catlin.

"If rawhide was desired, nothing further was done to the hide. If soft flexible skin was needed, a third step was taken. A mixture of brains and any one or several of the following materials, cooked ground-up liver, fats and greases of various kinds, meat broth and various vegetable products, was thoroughly rubbed into the hide. When well saturated with this compound, it was allowed to dry, then soaked in warm water and

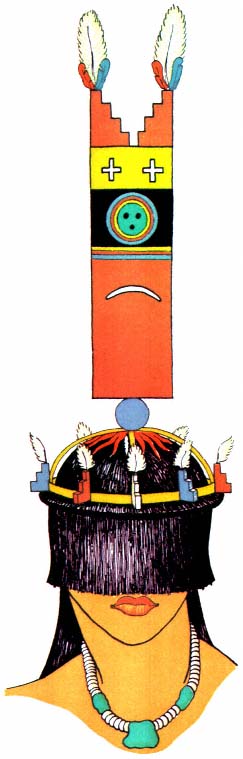

Plate 10.

Tablet headdress worn by the Zuñi Corn Maidens. The

natural hair shields the face. (After Stevenson, 1904, pl. 37.)

rolled up into a tight bundle. The final step was the stretching of the hide as the braining process caused great shrinkage. The hide was alternately soaked in warm water and pulled with hands and feet, pulled down over a rounded post, or stretched by two persons if the hide was large. Friction caused by rapidly pulling through a small opening was also resorted to to give greater softness. The dressing process was complete when the hide was nearly its original size and thoroughly softened and smoothed."[37]

Catlin describes a further step, that of smoking, which, he says, makes it possible for the skins, "after being ever so many times wet, to dry soft and pliant as they were before."[38]

It is true that the Indian dressed skin can be wet again and again and it will always dry with its original flexibility. This fact is made use of in the making of any special leather articles, such as moccasins and masks. The moccasin is cut to the pattern of the foot it is to cover, sewn, and packed in wet sand until saturated. The owner then allows it to dry on his foot, and shrinkage makes it fit perfectly.

The Havasupai, a group of seminomadic Indians who live in summer near their cornfields in Cataract Canyon—a deep chasm cutting into the south side of the Grand Canyon about a hundred miles west of the Hopi,—are also skillful tanners. They use a "process of rubbing beef brains and marrow and yucca pulp into the hides with the hands."[39] Many raw deer hides come to them from the Colorado River tribes farther to the west. These they tan and use in trade with the Hopi.

Among the Pueblos the tanning was done by the men; among the Plains tribes, by the women.

Pelts were cured in the same manner, but the hair was left on. The pelts, like the dressed skins, are impervious to water. A trader at Zuñi told me that the foxskin tailpieces (pl. 24) used in ceremonial dances were buried in damp sand for several days before being worn. They appeared, when brought out for wear, soft, sleek, and glossy.

Feathers

Throughout Indian lore, birds and feathers are prominent in myth and legend, in ceremony and drama. They are used as symbols in the religious and theatrical paraphernalia of the groups. In earlier days, they provided wearing apparel and were used lavishly in decoration. The Indian, living with few artificial aids, must depend upon nature and his own ingenuity to provide the decorative element.[40]

Birds were believed to possess the universal 'spiritual essences', and hence were rarely killed except as they were needed for food or as a measure to protect the newly sown corn. When feathers were needed for ornamentation, birds were plucked and their denuded bodies were en couraged, with artificial aids, to grow a new covering. The Zuñi plucking rites explain that the eagle's body is to be rubbed with kaolin, a white clay, and chewed corn so that more feathers will grow; the second growth will be very white.[41]

Of the many species of birds which inhabit these mesas and desert regions, certain ones have been predominantly associated with certain clans or moiety groups, or in some way connected with tribal divisions. Eagle, parrot, turkey, wild duck, goose, sandhill crane, crow, chaparral cock, dove, whippoorwill, golden warbler, magpie, hummingbird, and swallow are the names of clans, past and present, which have existed in some of the villages.[42] Such nomenclature appears to be only a name association, although there may be some totemic significance.

Some birds are associated with directions because of the color of their feathers. A prayer plume described by Stevenson allocates the long-tailed chat to the north, the long-crested jay to the west, the macaw to the south, the spurred towhee to the east, the purple martin to the zenith, and the painted bunting to the nadir.[43]

There are bird supernaturals which are impersonated in more or less stylized costumes. Among these are the eagle (pl. 24), red hawk, cock,

turkey, wild duck, kite, crow, quail, mockingbird, and hummingbird.[44] Eastern Pueblo Bird Dances include the eagle (pl. 23), the crow, and the snowbird. These latter dances were done without masks, character illusion being given through costume and action.

Macaw.

—Certain feathers were desired because of their colors (pl. 3). Those of the macaw were most highly valued, and they were also very difficult to procure. "Its feathers are highly prized by the Tewa for ceremonial purposes. They state that the feathers and also live ... [birds] were obtained from Mexico in former times".[45] Runners were sent to the south to bring back many brilliantly colored feathers (pl. 3) of this prized bird in exchange for skins and turquoises. The kachinas are said to "wear macaw feathers because the macaw lives in the south and they want the macaw to bring the rain from the south. They always like to feel the south wind because the south wind brings rain."[46] There were many local birds the feathers of which were highly valued for various reasons: goose, wild duck, owl, jay, oriole, yellow warbler, goldfinch, one or more species of small red birds,[47] and the hummingbird.[48]

Turkey.

—The turkey was domesticated at an early date. The Spaniards found many of these "cocks with great hanging chins,"[49] which roamed the country or were kept in large flocks chiefly to supply feathers for garments.[50] Turkey feathers are of some importance in ceremonial life. This is illustrated by a certain rite at Isleta, where the turkey feather as the "oldest one"[51] has a place of preëeminence, being set aside for the chief. Since the turkey is hard to raise, there is a belief at Zuñi that its feathers are a token of mortality and that no dancer should wear them except one who impersonates supernaturals or the dead.[52] At Cochiti turkey feathers are buried on All Souls' Day so that the dead may wear them in their dances.[53]

Eagle.

—"The eagle is symbolic of the sun or sky god."[54] His feathers, together with those of the turkey, are the most widely used. He is the messenger to the supernaturals and soars above the clouds to take prayers

from earth creatures to the Great Ones. The eagle always represents the direction of the zenith, or above; he is the only bird used to indicate the ethereal heights. As we learn from the eagle myth: "The katcinas ... wear these feathers because the eagle is strong and wise and kind. He travels far in all directions and so he will surely bring rain. The eagle feathers must always come first."[55] Both the long, stiff, tail and wing feathers and the downy white breast feathers (pl. 5) are important. The downy feathers belong to the Sun priest;[56] others may use them when rain is very much needed. In this connection they are primarily worn by the kachinas. In certain curing rites the doctors take 'sorceries' from the body of the patient. They hold eagle tail feathers in each hand and by brushing the patient and striking the feathers in one hand against those in the other they throw the evil in each direction: north, south, east, west, zenith, and nadir.[57] Eagle feathers generally enclose the sacred ear of corn; and they are used for leading persons to ceremonial places, for making certain ceremonial gestures, and for dipping medicines or sacred water from ceremonial bowls.[58]

In the Snake Dance of the Hopi, one of the dancers follows the snake carrier and continually brushes the waving rattler with an eagle-feather wand in order to prevent him from striking. The gatherer, or guard, who picks up the wriggling snakes after their dance turn and before they can escape, controls them with eagle plumes. The brushing movement along its back prevents the snake from coiling, which it must do in order to strike. Because of this the Indian declares that the eagle possesses the power to charm the snake by flying above it and gently caressing it with his wings.[59]

Father Dumarest describes the eagle trap used at Cochiti to catch the birds alive. The hunter is concealed in a deep and wide hole which has been covered with brush. A rabbit is placed over the opening for bait. In the bottom of the hole is a bowl filled with water in which the eagle

Plate 11.

Half mask, made of a strip of leather with a beard of horsehair.

is mirrored as it circles overhead. The hunter can thus watch its movements, and when the bird swoops down upon its prey he reaches through the brush and makes it captive.[60]

In the western pueblos young eagles are stolen from the nests. At Hopi there are even property rights[61] in eagles, and clan-owned nests are watched so that one small bird can be taken from the brood and the rest left unharmed. Live eagles, and macaws also, are kept in cages[62] on the housetops or in shelters at the side of the village. Even in Coronado's day "there were also tame eagles, which the chiefs esteemed to be something fine."[63]

Duck.

—The feather of the wild duck is often spoken of as the "looking back" or "turn around" feather.[64] Its iridescence adds beauty to any ornament. Although the wild duck is not significant in myth or religion in all the villages, Hopi, Zuñi, Isleta, San Felipe, and Jemez appear to hold this bird sacred. At Zuñi it is said that the supernaturals assume the form of the duck in order to swim the river to the Sacred Lake, their home.[65]

Crow and owl.

—The crow and the owl are two birds of adverse symbolism. Bad fortune accompanies the "kaa, kaa" of the crow. He is the persistent thief who follows the sower and then himself makes his thieving known. He is often associated with witchcraft,[66] and always with bad luck.[*] Certain Zuñi kachinas wear collars of crow or raven feathers (pl. 5). These frighten the children as well as drive away bad luck.[67] The owl is often symbolic of witches and witchcraft, probably because of its nocturnal habits.[68] We sometimes find bunches of owl feathers used as decoration on kachina masks.

The "summer birds" .—All those which are brightly colored, as, for example, the jay, red hawk, road runner, bluebird, oriole, and hummingbird,[69] often have some special significance. The oriole, or chat, is the bird of the north since yellow is the north color, and the blue jay supplies the priest with feathers which he is entitled to wear in his hair on ceremonial occasions.[70] These small birds are caught in traps of horsehair

* At Laguna and Zuñi.

and sticks,[71] or on a plant called "crowfoot." They are kept in small cages on the housetops.

Many feathers are connected with special persons or incidents. The downy eagle feather dyed red (pl. 7) is a sign of the priesthood at Zuñi.[72] The sparrow hawk is associated with the Black Eye, a priest-clown group at Isleta, while the Koshare, another group, use the turkey.[73]

To an Indian the downy white feather is very close to life itself. "The feather is the pictorial representation of the breath," and "breath is the symbol of life."[74] There is hardly an act of ritual or drama without the use of feathers, and all feathers for ceremonial use must come from the living bird.[75]

Feathers on the prayer-plume offerings planted at almost all the villages were supposed to "provide clothing for the supernaturals."[76] Just as food, accompanied with a prayer, is sent to the other world when it is cast into the fire or into the river, so these feathers are sent to clothe the Great Ones.[77] At Jemez the erect turkey feathers bound at the back of the prayer stick represent the red-and-blue-bordered white Hopi blanket[78] —a recognition in form and pattern of an actual garment. More often the stipulated arrangement of feathers on the prayer stick is a matter of ritual form and the resulting kachina costumes do not bear a relationship to their supposed origin. At all events, it is true that the kachinas are conspicuous for their beautiful feather ornaments.

Each particular rite or entertainment has its specified method by which feather ornamentation is employed. Sometimes the feathers are painted, in a stylized manner, on the articles or emblems used in the rite; this obviously was taken over from its origin in basket and pottery decoration. We find them also on a tablita form over a mask, and on the cheek of an unmasked dancer.[79]

Aside from the robe so often indicated on the Shalako Kachina doll, feathers are used on ceremonial costumes purely as ornamentation. Single feathers are hung alone or in groups from belts and arm bands (pl. 35)

by buckskin thongs or homespun cotton cord. They are often tied to the corners or centers of kilts and blankets (pl. 7). Headdress and mask ornaments are made of feathers fashioned together in various patterns. Accessories (pl. 30), either worn or carried, are peripherally trimmed with feathers or made of feathers entirely.

The methods of application vary. The quill may be tied on with buckskin, yucca, or cotton cord. Cornhusks may be folded and wrapped tightly around the quill end, making a holder. Buckskin may be used in the same manner. Holes may be bored in gourds, corncobs, or wood, and feathers stuck into them. Down is even applied to horsehair and wool with a syrup made by boiling the juice of the yucca fruit.

When colored feathers are not available, the white ones are stained the desired colors. Downy eagle feathers are dyed red to indicate membership in societies. Furthermore, since feathers naturally lend themselves to varied and graceful forms of ornamentation, it is only the rigid rules prescribed by ritual which prevent artist creators from making endless objects in this medium. As a consequence, new forms are created only when a new character is introduced, and ordinarily the same ornaments differ only as the ability of one craftsman exceeds that of another.

When not in use, sacred feathers are kept carefully packed in special boxes, made of cottonwood, which have ingenious sliding lids held in place by fitted pegs. At Jemez the sacred feathers are laid away wrapped simply in buckskin.[80] Each ornament and feather is renewed and redecorated for every dance series; for many days before a performance the priest works secretly with others within the kivas to get them ready. With this constant renewal of parts and the variability of human craftsmanship, it is small wonder that the forms change despite the fact that the artist has carefully followed a specified plan. In the work of renovation only hand-spun cotton cord can be used, as that has a sacred significance. Cornhusk is used as a firm base upon which feathers can be fastened, or it may be wrapped around the quill to hold the feathers in a rigid position.

There is an interesting headdress in the Buffalo Dance (fig. 25, p. 189). It consists of a white deerskin band about two and one-half inches wide, on the right side of which is fastened a black buffalo horn and on the left a fan of six eagle tail feathers firmly bound with cornhusk and tied in place with a buckskin thong at right angles to the quill ends.[81]

Feathers are used on other parts of costumes. Buckskin shields worn on the back may be edged with feathers or have some special feather treatment at top or bottom. Again, eagle feathers are sewn to deerskin or cornhusk bands which follow the arm contour from neck to wrist to provide the wings of the eagle dancers. Fan-shaped tail ornaments of eagle feathers are also made.

In the ceremonial dances, various articles carried by the dancers are distinguished by the feathers attached to them. The presiding priest carries a special feather wand to indicate his position and the particular office which he is performing.

Nature Forms

A great wealth of economic and aesthetic material is found by the Indian in the plants and trees that grow on every side. Roots, stems, leaves, and fruit give variously of food, medicines, and clothing. Certain of the initiated are believed to be blessed with the power to communicate with the plant world. Many plants are held sacred, "for some of them were dropped to the earth by the Star People; some were human beings before they became plants; others were the property of the gods and all, even those from the heavens, are the offspring of the Earth Mother, for it was she who gave the plants to the Star People before they left the world and became celestial beings."[82]

Fir, oak, cottonwood, corn, and squash supply names for clans and individuals. In the clanless villages where the two-moiety division is found, "Squash" is applied to the group of Summer people and "Turquoise"

Plate 12.

Face mask. The nearest approach to realism.

to the Winter people: the one suggesting summer sun and growth; the other, winter cold and storms from the sky.

In order to satisfy his aesthetic urge, man has always bedecked himself in season with blossom, fruit, or leaf as the form or color has pleased his eye or enhanced his beauty. No discussion of the costumes of the Pueblo Indian would be complete without reference to these nature forms, which, though as used may be in either the fresh or the cured state, have come originally from living plants and trees.

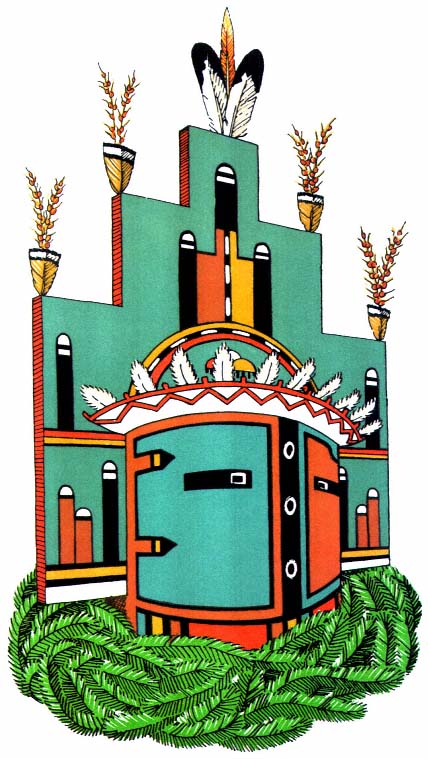

Evergreen.

—The most conspicuous nature form, and that regarded with the greatest reverence, is the spruce tree and its branches. In special rain ceremonies the Rain priests and the dancers who personate the Rain Makers address the spruce trees, invoking them to extend their arms (referring to the branches) and water the earth. The breath from the gods of the undermost world is supposed to ascend through the trunks of these trees and form clouds behind which the Rain Makers work.[83] The Douglas spruce is the most desired[84] and great effort is often made to obtain it from the deep canyons of the mountainous country where it grows. Among the Tewa, officials go out the day before the ceremony to bring back its branches. In some of the performances small trees are set up in the plaza after midnight and the next day are worked into the dance pattern. At Hopi, spruce is more difficult to obtain. A runner is sent to bring it from the mountains, and this takes from early morning till late at night. At Hopi, also, the branches are planted and the children are amazed, when they awaken, to find "trees" growing in the plaza—a phenomenon explained as one which accompanies the supernaturals who are about to dance there.

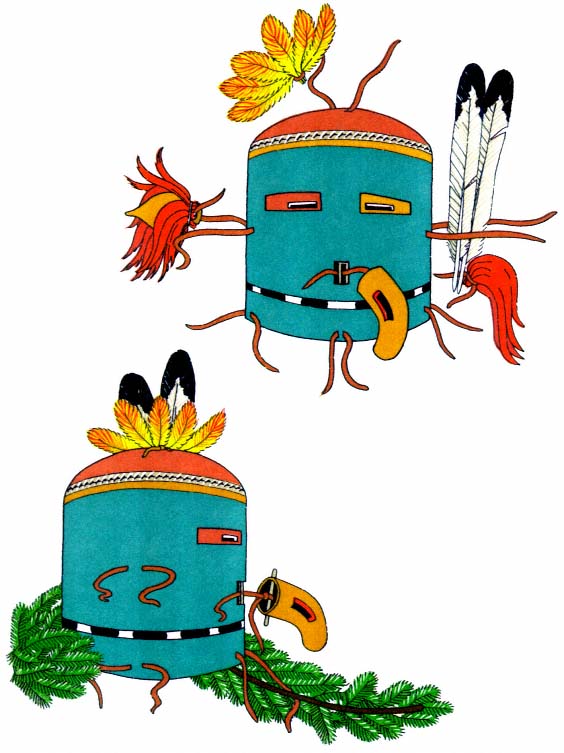

Performers wear sprigs of spruce stuck in the belt, and in arm bands, and sprigs are carried in the hands. Small branches are tied together with yucca cord to form anklets (pl. 6) and great collars (pl. 4). Occasionally, spruce forms part of a headdress or fills in the back of a mask. Spruce branches are never thrown promiscuously about after ceremonial use;

they are dropped over the cliff or into the river, or are buried in the sands at the river's edge to be washed downstream with the next floodwater.

Used on the ceremonial costume in the summer dances, evergreen is the symbol of life. Green yarns embroidered on kilts and ceremonial blankets have the same connotation.

If spruce cannot be obtained, juniper may be substituted as an evergreen. Firebrands are made from juniper bark, since it burns very slowly and thus is a good means of transporting live coals. Torches of juniper are carried in night ceremonies. At Santa Clara and at Hopi a special Old Man is impersonated by the wearing of a juniper-bark cap or headdress.

Gourds.

—The gourd was one of the aboriginal plants cultivated by the Pueblo Indian before the advent of the Spaniards. It has an important place in both their ceremonial and domestic lives. The gourd, in fact, is indispensable to the Pueblo Indian; it is a bucket, a dipper, or a bowl as the need arises. Several species were grown. Some were small, some were long-necked, and others grew flat or round. By running the vine on a pole so that the green fruit hung down it was possible to develop extremely long, thin gourds; and it was possible to flatten them out by placing a weight on one side. Under stimulating conditions very large gourds have been grown. There are two masks made of gourds in the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation.[85] One of them is large enough for a man to wear. With the lower end cut off, it would go over his head and rest upon his shoulders. There were holes for eyes and mouth. A smaller gourd made the snout, and the features were painted on. The other mask could have been worn by a boy.

The shell of the gourd is scraped clean of seeds and pulp and then thoroughly dried. As the gourd is a material more easily worked than wood, and, for the Hopi and the ZuÑi, much more easily available, it is made into snouts and beaks and ear bobs for masks. A large number of these are kept on hand at all times, to be available for any dance ceremonies. Rarely, two gourds will grow so much alike that the necks can

be used as horns on an animal mask. When several are found of the same size and shape, they are carved into flowers to decorate a headdress or arm bands. The heads of the sacred Plumed Serpents are made of gourds.[86] The mouth is cut to show two rows of teeth, between which a red leather tongue is allowed to dangle. Gourds are made into rattles, round or fiat, with the necks serving as handles (fig. 20, p. 146). Certain phallic devices are made of the long variety of gourds and these symbolize fructification.[87]

Figure 13.

Headdress with flowers made of grounds.

Yucca.

—Yucca, or Spanish bayonet, is a low-growing desert shrub. Its sharp, pointed leaves branch out stiffly from a single stem. The blossoms are white and appear in a cluster on a shoot several feet above the leaves. This plant is called "soapweed," and because it produces an excellent lather it is indispensable to the desert Indian. The roots are crushed or pounded with a stone and put into cold water to steep. Within a few moments a thick lather can be produced by brisk stirring. The fibrous parts are removed and the shampoo or laundry is ready. The glossy black hair which is a source of great pride to every Indian man, woman, and child is washed as often as once a week with this soap lather. No ceremony is complete without hair washing. Among the Hopi every infant when it is named, every girl on her marriage day, every boy upon initiation into a secret fraternity or a medicine society—all must have their hair washed. Before a public entertainment every dancer, and indeed every person in the village, is expected to wash his hair. At the conclusion of a ceremony every impersonator is discharmed—that is, the supernatural spirit which he has assumed is washed away in the shampoo and he becomes human once more. In all these ceremonies the yucca suds represent

clouds. Ceremonial bowls full of suds are often found on the altars; they are imitation magic denoting that clouds are wanted to bring rain.

The long, flat leaves of the giant yucca are carried by warriors and whipping impersonators (pls. 5, 6, 35, 36).[88] Initiates are purified by whipping.[89]

The costumes of certain kachinas of the Hopi have skirts made of stiff yucca leaves.

Corn.

—Everything connected with corn is sacred. For the Pueblo Indian, life itself depends upon the growth of corn. Since the beginning of time it has been his greatest source of food. Directly and indirectly his entire existence is related to the culture of corn. Land is owned by individual or tribal group, but wealth depends upon the production of corn. Soil and water are of prime importance because they make possible its growth. The Pueblo Indian believes that rain and snow are sent by the supernaturals and can be obtained only by prayer and ceremony, and thus have come into being the Weather Control groups which form the underlying structure of Pueblo life.

As the staple food, corn is eaten fresh or is dried and stored for the future. The need of safe storage space has had its influence upon the structure of house and village. As the basis of Pueblo life is corn, it is not surprising to find it a conspicuous feature of the ceremonial life. The perfect ear, with its special covering, is the life fetish of each individual, and is often placed upon the society altars or worn secreted in the belts of the dancers. Ears of appropriate colors are laid around the medicine bowl before the altar. The bowl represents the center and the corn the six cardinal directions.

White corn meal, finely ground, is the women's special offering, equivalent to the prayer plume of the men. However, both men and women sprinkle corn meal on the dancers. The priest sprinkles a 'road' into the dance plaza for the impersonators to follow, or with meal he designates

Plate 13.

Helmet mask, Hopi Pawika. Occult symmetry

achieved through fixing of ornaments.

the 'way' to the edge of the village, where the populace go to offer prayers to the Sun. At the end of the Hopi Snake Dance the women describe a great circle with corn meal. The snakes used in the dance are heaped in the center of this circle; then, after another prayer and a sprinkling of meal, each member of the Snake Dance group grasps as many of the wriggling reptiles as he can and dashes away in one of the cardinal directions

Figure 14.

Cornhusk flowers worn by

Powamu dancers, Hopi.

to deposit his burden far out on the desert, whence it is to return to the world below carrying to the gods the prayers for rain.

Corn in various forms is carried or worn by the dancers. Sometimes it is the actual ear, sometimes the symbolic representation of it—both three-dimensional and painted. Cornhusks are used, and even the cob. The whole grains are always carried somewhere on a dancer's person to symbolize prayers which accompany the dance. The knobs of the masks worn by the clown Mudheads have corn and other seeds tied in them.

Ears of corn are often carried by impersonators and women dancers as an accessory to their parts, or they are attached to the tablita worn by the maidens. The Sio Shalako mana, the Zuñi Shalako Maiden of Hopi, is shown with a stylized ear of corn on the forehead (pl. 18). Painted representations are found on masks, head boards, and tablets which are carried in each hand. The corncob is useful as a holder into which the feather

quills are stuck, thus forming a feather bouquet. I have seen an example of a curved cob, stained from black at one end to red at the other, used as a beak on a mask.[90]

The dried husk is a useful part of the corn. It is slit into ribbons and used to decorate the hair (pl.39) and caps of the clowns.[91] Balls of husk are covered with cotton cord at the head of the long fringe on the plaited ceremonial sash,[92] representing corn and rain and the desire for bountiful crops. Tightly twisted cornhusks form the framework and mounts for feathers in many ornaments. Cornhusks wound into a circlet may be worn on the head to support wooden symbols of lightning and clouds.[93] Skillful arrangements of cornhusks simulate teeth and mouths on masks. Cornhusks are rolled into cones and used as earbobs, or are fashioned into collars at the bottom of masks. Erna Fergusson colorfully describes the manufacture of gay cornhusk flowers: "They smoothed the pale gold husks on their knees, tore them into the right shape, and then, dipping twisted yucca fiber into shallow pottery bowls, they applied a light-red paint to one half of each leaf. The work was apparently negligently done, while conversation went on, but the results were beautiful. Soon four petals were ready, and then they were quickly twisted into the shape of a big open flower, like a squash blossom, tied, and laid aside. Without any apparent effort or hurry each man soon had beside him a pile of pale-gold and red blossoms."[94]

Cotton.

—I have discussed the spinning and weaving of cotton into fabric, but with the Indian its ceremonial use does not stop there. It has a place in almost every ritual. The Zuñi name for unspun cotton is "down," and down, as I have said, is the sacred feather of life, the breath of the supernatural. It symbolizes clouds[95] and snow and is often stuck on the horsehair beards in place of eagle down. The tops of certain masks are covered with raw cotton to indicate that those gods are associated with rainmaking. Handmade cotton cord is always used in prayer plumes and for the purpose of fastening together feathers used for ornaments on the

ceremonial costumes. It is placed across a road leading into the village to indicate that a ceremony is taking place. We often find the loosely twisted cord hanging from the crown of a wig in definite contrast to the black hair (pls. 3, 17).

Herbs and flowers.

—The Pueblo plant forms are limited to those which will grow in a land of much sunshine and little rain. However, these are numerous. And since it was not always possible to travel great distances for herbs and leaves, the Indian was forced to employ that which was near at hand.

In wide desert spaces, colors and plant forms, flower and leaf, stand out in brighter shapes and make a more poignant appeal to the aesthetic sense. The sagebrush, the sunflower, are not homely, commonplace; they are vivid and beautiful. I remember the blanket-wrapped form of a young man who impulsively rushed out of the sacred dance room to pluck the sunflowers across the barbed wire fence and carried them back into the shadow of the dark kiva. When the dancers emerged a few minutes later to take their places in the dance pattern, each carried with the sprig of evergreen the nodding, golden heads of the sunflower. This was not a conventional part of the paraphernalia of the dance; it was evidence of that fundamental, primal thing which those who live close to nature so readily feel. The feathery pigweed may be carried and tossed to the spectators who line the edge of the plaza. Sagebrush adds a soft gray-green to the hand tablet of the Corn Maidens, and sand grass gives a brittle edge to tablita and wand. Mouse-leaf blossoms mixed with ocher earth will color bodies yellow, and crushed barberries give them a purple hue. To each dancer, after he has dressed, are given the powdered flowers of the wild buckwheat in order to assure him grace. White primrose blossoms are rubbed over the necks and arms of those who impersonate the Zuñi Corn Maidens, so that they may dance well and please the "white shell mother of the Sun Father" who will surely send rains to moisten the earth and make the corn grow.

Decoration

When primitive man first sought to make himself attractive, he chose from his environment objects which were bright or colorful and wore them in his hair, strung them about his neck, looped them about his middle, or otherwise applied them to his person where application was possible. Garments evolved from this desire for ornamentation of the body and were used as protection from the elements or the immodest eyes of men. Hilaire Hiler points out that "ornament often exists without clothing, but clothing seldom, if ever, exists without ornament."[96]

Articles of clothing of the Pueblo Indian are the bases upon which the arts of the painter, the dyer, the embroiderer, and the weaver are practiced. Garment ornamentation is achieved through painting in pigment directly upon the surface of the fabric, the application of colored yarns or other materials by embroidery or appliqué, and the weaving of variously dyed yarns into a patterned fabric.

The effect of ornamentation varies with the method and the material used. Heavy embroidery raises the surface and stiffens the garment in the area in which it is applied, and painted designs may cause a cloth to hang rigid because of the adhesive matter used to make the pigment cling to the surface. On the other hand, a cloth made of dyed yarn may not vary at all from its uncolored prototype, since the pigment, though changing the color, does not affect the physical character of the cloth.

Color.

—Since love of color is an inborn trait of the human race, it is not surprising to find the Pueblo Indian of the Southwest exercising it, albeit unconsciously. Colors abound in his kingdom of sandy space and limitless sky. The earth shows a myriad hues, played upon incessantly and with endless change by the brilliant sunlight or the passing clouds. The sky exhibits the pageantry of all those shifting forms of day and night, summer and winter, fair weather and foul, which are called the elements.

Plate 14.

Basketry mask. Feathers are held

in place by a braid of cornhusk.

The parade of color passes from the pale iridescence of dawn through the white noon to the golden flamboyance of sunset, and on into the crisp blue-black of the star-pierced night. It is seen in the red and purple where the watercourse has gashed the mesa side; in the brittle-edged clumps of dark green piñon against a golden monotone of roiling sand; in the soft gradations of green and silver sagebrush and cactus-strewn flats; and on the great rolling mesa tops where blankets of purple lupin and yellow sulphur flowers have been carelessly flung across the sweep of space. The Indian had but to step to his housetop to see around and above him all these wonders of nature. He began very early to relate them to certain phases of his life.

Out of these associations grew a kind of symbolism in which color represented ideas and objects, mythical and real alike. Colors were related to the six directions: yellow to the north, blue to the west, red to the south, white to the east, many colors to the zenith, and black to the nadir. The origin of these associations is clothed in mystery.[*] It is obvious that yellow colors the sky to the north before the angry winter storms sweep down from the mountains, and it has been suggested that the Pacific Ocean to the west accounts for the blue.[97] Red is applied to the south because of the ruddy warmth of summer, and white to the east because it suggests early morn and the rising sun.[98] The many colors of the zenith reflect the sky from which all colors come, and the nadir is black because of the dark inner worlds from which in myth the Pueblo peoples emerged.

Paralleling these directional hues are the colored ears of corn used on the altars and incorporated into the legendary background of the social and religious life. Certain of the supernaturals are characterized in sets which correspond to the cardinal directions and colors. During ceremonies these supernaturals appear in the masks and body paint of their world quarters. The Zuñi Salimapiya[99] are an interesting example of one of these

* Some of the pueblos either lack this association altogether or have a variant. "Taos appears to have no directional association with color" (Parsons, 1936a , p. l05). In Isleta only five directions are recognized and there the colors are: east, white; north, black; west, yellow; south, blue (Parsons, 1932, p. 284).

series (pls. 5, 6). There are twelve of them, two for each direction. They appear together only once every four years; at other times two of them, each of a different color, may be seen simultaneously. The black may appear with the many-colored, representing respectively the nadir and the zenith; again, the yellow may appear with the blue, representing the north and the west. In 1879 Matilda Stevenson saw two of these directional supernaturals at Zuñi, which she describes as follows:

"They represented the Zenith and Nadir, the one for Zenith having the upper portion of the body blocked in the six colors, each block outlined with black. The knees and the lower arms to the elbow have the same decoration; the right upper arm is yellow, the left blue; the right leg is yellow, the left blue. Wreaths of spruce are worn around the ankles and wrists. The war pouch and many strings of grain of black and white Indian corn hung over the shoulder, crossing the body. The upper half of the Salimapiya of the Nadir is yellow and lower half black; the lower arms and legs and feet are yellow, the upper arms and legs black. He wears anklets and wristlets of spruce, a war pouch, and strings of black and white corn."[100]

Ruth Bunzel, writing in 1932, says the Blue Salimapiya "has his mask painted with blue gum paint, his body with the juice of black cornstalks ... thighs white ... he wears a special kilt called the Salimapiya kilt. It is embroidered like the ceremonial blanket with butterflies and flowers."[101] He also wears a blue leather belt and spruce anklets, and his feet are bare.

The impression of the general public, when viewing Indian motifs in costumes and decoration, is that they are composed of purely symbolic patterns. This is rarely true. Many designs are used only for decoration, and if by chance they symbolize an object, quality, or idea, it is merely by association. The emotional response to color association differs with the group, and what becomes a symbol to one group remains only a decoration with another.

Green suggests grass, and it may mean life and fecundity. Blue-green

is reverently used, as it is always associated with the sky. It is a 'valuable' color and of great religious import. The blue prayer stick is male and connotes the sun; the yellow represents the female and the moon. The turquoise stone is regarded with great reverence and the wealth of a man is displayed by the quantity of turquoise he wears about his neck. "Yellow on the face represents corn pollen, and brings rain;"[102] and yellow body paint is used by the Squash groups or Summer people. On the other hand, "red paint on the body is for the red-breasted birds, and the yellow paint for the yellow-breasted birds, and for the flowers and butterflies and all the beautiful things in the world," and again, "the spots of paint of different colors ... are the raindrops falling down from the sky,"[103] or those same spots may represent the drops of blood of a little boy who, in a myth, was killed by the supernaturals. They ever afterward wore the spots on their masks.[104]

From the frequency with which designs are repeated on like objects, and the same colors used, one can be certain that there is a definite symbolic pattern for the ceremonial use of color. We do not know whether the source of this symbolism is known to others besides the priests who prescribe it and who have acquired their knowledge from priests of the preceding generation.

The association of color is one thing, the application another. The range of hues used by the Pueblo Indian was limited to the colors that were available and to the manners in which they could be used. Materials were colored by three methods: dyeing, a process by which a permanent union is brought about between the material to be dyed and the coloring matter applied to it; staining, a method by which colored particles become entangled in the surface of the fiber but can be removed by washing or rubbing; and painting, by which a pigment is applied to the surface. McGregor says:

"Dyes or pigments used in coloring yarns or fabrics may be divided into two general classes: organic and inorganic. In prehistoric cotton

fabrics the inorganic dyes are by far the most common, and consist largely of three colors: red, produced from hematite or some other iron oxide; yellow, from a yellow ochre; and blue or green, produced from copper sulphate. These inorganic dyes may be readily determined by a superficial examination with a medium-powered microscope, for the dye material does not penetrate the fiber but clings to it in the form of grains. Organic dyes seem to consist of only black, dark brown, and a light blue. These dyes are relatively permanent and cannot be washed out, as can the inorganic types."[105]

Paints and stains.

—The processes of painting and staining which employ inorganic pigments are used to color the face and body, articles made of skin, wood, and nature forms, and certain fabrics for which the required colors cannot be obtained in permanent dyes.

These earth colors are found in the mountains and valleys surrounding each pueblo. Most of the villages are thus able to obtain their own supplies, but often color in the form of cakes or powder is obtained by trade with other Indians. The Zuñi procure their turquoise blue mask paint, ready for use, from the Santo Domingo because they believe the color is better.[106] Mrs. Parsons relates that a Jemez Indian once asked her to get some red face paint from the Hopi for him. "He said they had the best."[107] The hue of these pigments varies greatly with the locality in which they are found and the purity with which they can be obtained. A report on Acoma suggests that the original earth color is none too pure, but by separating the ground particles a fairly clear color is obtained. "A yellowish rock is ground fine and the dust mixed with water. The sediment is thrown away after being allowed to settle twice. The third accumulation of sediment is kept."[108]

Some colors come in rock form; others are a clay. "Iron tinged the earth red, brown, yellow, orange and intermediate shades. Copper produced

Plate 15.

Mountain sheep mask, Hopi. Molded horns of deerskin carry

symbols of clouds, rain, and lightning. The vizor is of basketry.

Figure 15.

Containers for pigments used in painting ceremonial objects.

the blues and greens. Black came from iron and magnesium."[109] The pigment, from whatever source, is ground in a stone mortar or on a metate with a mano. The process of grinding is often a special ceremony at which the young girls are invited to do the grinding while the men sing to them.[110] At other times the grinding is a secret rite and is done in the kiva by the society head and his helpers.[111] The ground powder is mixed with water and used directly, or it may be combined with an adhesive, substance, such as piñon gum or the juice of yucca fruit,[112] to make it more permanent. Another method of fixing a permanent color is to squirt over it a water in which ground-up pumpkin seeds have been steeped for a long time.[113] A shiny surface is made possible by mixing the paint with yucca juice or the yolk or white of eggs.[114] A glaze of albumen from the egg white may be applied over the paint,[115] or a spray of cow's milk blown from the mouth makes the object bright and shiny.[116] Grease is mixed with body paint to make it adhere and also to impart a sheen.[117]

Paints are applied with the fingers, a stick, or brushes of yucca fiber. A piece of yucca leaf is selected and chewed to separate the fibers and cleanse them. This makes a very good brush. A different brush is used for each color. The pigments are mixed in small pottery cups made specially in groups for that purpose and decorated with designs relating to water and rain. Sometimes flower petals and shells are ground and mixed with the powder to give it more 'power' or to make it more sacred.

Even today the paints for ceremonial purposes are of native make. It is a rare and decadent society which permits the use of any commercial paint on the masks, body, or dress of a dancer.

White is obtained from a white clay (kaolin) which is soaked in water or ground and used as a powder—the counterpart of the fuller's earth, or

white clay paste, used by Greek and Roman artisans to cleanse and whiten their cloth. All white garments are treated with it before they are worn. This clay is found up and down the Rio Grande and is traded to the Zuñi by the Acoma.[118] Masks are always painted white before any other color is applied. This forms a ground coat to fill up pores and give a smooth surface. White is often used as a body paint or powdery.[119]

Black may be obtained from various sources. A pigment in common use comes from an ore (pyrolurite, a hydrated oxide of manganese)[120] which is mined.[121] This is used on prayer sticks and masks. Chimney soot is also used, especially for the eyes of a mask—being, for that purpose, mixed with the yolk of an egg to produce a gloss.[122] Corncobs, carbonized and ground, make a highly valued paint for masks. At Zuñi, they are found in the ancient ruins and carefully preserved for this purpose. Similar to this is the charcoal of willow which, when ground, is mixed with water for a body paint.[123] Corn rust or fungus mixed with water is used especially for a body paint; mixed with yucca syrup, it makes a shiny black paint which is used for masks.[124] An iridescent blackish substance ("black shiny dirt") is found in the water washes after a rain. It is probably the fine grains of quartz, sphalerite, and galena, the last-named being a ground concentrate of zinc ore.[125] This is mixed with grease and applied to the body, or it is mixed with yucca juice or piñon gum and applied to masks. Masks are also made to shine by the use of mica (micacious hematite), which is applied over black with some form of adhesive.[126]

Pink is a body paint used especially by the sacred clowns, the Mudheads (pl. 40), and by the Kokochi and other masked gods.[127] It is a clay[*] obtained by the Zuñi from the shores of the Sacred Lake where the kachinas live. Every four years a pilgrimage is made there to secure it. It is kept in chunks until wanted, and then is wet with the tongue and rubbed on the body or mask.

The reds and yellows are ochers or oxides of iron. These rock forma-

* Kaolinite or a similar hydrated silicate of alumina.

tions, hematite and limonite, constitute the rugged edges of the mesa and the weird towering shapes that stand, massive and solitary, on the desert throughout all the great distance from the Grand Canyon to the Rio Grande.[128] Certain cliffs or mounds produce colors of greater purity than others do, and these the Indians have mined for centuries. One cave on the north side of the Grand Canyon produces a fine red ocher which is traded to the Hopi by the Shivwits, a tribe of Indians who dwell to the north.[129] Other mines are within easy reach of all the pueblos. The red is generally ground on a stone with water until the water becomes red. It can be used directly on the masks or the body. If light red is desired, the red water is mixed with pink or white clay. At Zuñi the yellow ocher is ground with the petals of yellow summer flowers (the buttercup) and abalone shells. This makes a very potent 'medicine.' When mixed with water, it becomes a sacred paint.[130] Another yellow is made of corn pollen. When mixed with the boiled yucca juice, it produces a glossy paint. It is thought to be flesh color.[131] At Laguna the faces of the dead are painted with corn pollen.

The most important color is turquoise. This blue-green paint is an oxidized copper ore (azurite and malachite in a calcite matrix).[132] It is found in the mountains to the east of the Rio Grande and is traded by the pueblos of those regions to the Hopi and Zuñi. Cakes or balls of this color are made by grinding the ore to a fine powder, mixing it with water, and boiling with piñon gum. The cakes can then be put away and kept indefinitely. A method of painting masks at Acoma with this pigment is described as follows: "One puts some of this substance into his mouth with eagle feathers, chews it for some time, then blows it onto the mask. The breath is expelled with it, giving the effect of a spray."[133]

There are also stains from plants which are used to color the body. Pink is produced by boiling wheat with a small sunflower,[134] and purple can be obtained from the chewed stalks and husks of black corn. An example is seen on the body of the blue-masked Salimapiya (pl. 6). The

purple obtained from crushing the berries of barberry is used on the body and for painting ceremonial objects.[135]

Dyes.

—The organic colors or dyes of the Pueblo were very limited. Certain trees and bushes yielded colors that were used to dye the yucca fibers, but with the advent of cotton the process became difficult. It is a well-known fact that cotton is the hardest of all fibers to dye. Specimens of native dyed cotton are rare and the colors are always drab and faded. It appears, then, that the prehistoric Pueblo people had no cotton garments of strong colors, and this made the need of brilliant ornamentation imperative.

Brown dye could be obtained from alder bark, dried and finely ground. It was boiled until it became red, and then was cooled. Deerskin soaked overnight in this liquid turned a brilliant red-brown. This was the favorite color for moccasins (pl. 33), Hopi fringed leather kilts, arm bands, bandoleers, and anything fashioned of deerskin. Sometimes the alder bark was chewed, and the juice ejected upon the deerskin, which was then rubbed between the hands.[136] Cotton cloth took only a small quantity of this dye and turned reddish tan.

A blue dye was made from the seeds of sunflowers.[137]

New colors came with the introduction and use of wool. Woolen fibers take dye much more readily than cotton. By this time the Navaho had learned the art of weaving from the Pueblo Indian. Alongside this knowledge of weaving there developed a new method of dyeing, as is evidenced by the well-known Navaho blankets. Unquestionably there was borrowing back and forth between the two groups. It is possible to say, then, that the Pueblo native dyes were similar to those of the Navaho.[138] These dyes were made from the leaves, stems, and roots of plants and shrubs and certain earth fillers, with use of piñon gum and a mordant of juniper ashes to make the color lasting. There were black, dark red, green, and

Plate 16.

Humis mask, Hopi. The terraced tablet over the helmet is

decorated with symbols of the rainbow and germinated seed.

the various yellows. From time to time indigo was imported from Mexico, along with other dyestuffs.

Since 1880, good commercial aniline dyes have largely taken the place of the native colorings. It is now rare to find a woolen blanket colored with native dyes, and even rarer to find, on cotton cloths, woolen embroidery which is native dyed. I have seen a few specimens in museums and private collections. The native dyes are soft and exquisite in their beauty. Once these are seen, the modern greens and reds appear harsh and overbrilliant.

Embroidery.

—Pueblo Indian embroidery is a pure form of ceremonial decoration. It is found on dance kilts, ceremonial mantles (pls. 7, 22), and the dresses made of hand-woven strips of cotton cloth (pl. 1). Occasionally the ordinary blue woolen dresses are embroidered with simple borders. The designs are highly conventionalized and dynamically abstract, with bold forms and geometric patterns.

"The art of embroidery as now practiced is a fairly recent one and is probably an outgrowth of the painting on kilts mentioned by Espejo or of the raised patterns found in weaving."[139] It is probable that no needlework decoration was done by the Pueblo Indians before the coming of the white man, since no examples are extant which do not utilize woolen yarn. It was the white man who brought the sheep. The yarns employed today are almost always commercial yarns or aniline-dyed hand-spun wool.

Rectangles of white cotton cloth, equal in size, are made into ceremonial mantles and dresses; one is worn hanging from the shoulders, the other is fastened around the body and held with a belt. They are similar to the wedding robe of the Hopi bride, which is completely white. It is later embroidered by her husband or a male relative for her use in ceremonies.[140] The same style of robe is made for god impersonators and priests. The decoration motif at the bottom "takes the form of a broad band of black wool with two vertical stripes of green appearing at intervals. On these broad borders the only space not completely covered is

a thin meandering line of the white cotton base which appears diagonally crossing the black and green. This white design-line creates a strong off-balance movement to the general vertical embroidery, seeming to exaggerate the movement of the dance in which it is used."[141] The upper edge of this band is terraced, and frequently through its center may be seen diamond-shaped medallions with designs of clouds, rain, squash flower, and butterfly symbols[142] —brilliant jewels of color. The design motif may differ among the pueblos, but the effect is always the same. The upper border is narrower and has only the green stripes and white meandering lines to break its solidity.

The rectangular dance kilts are also made of white cotton cloth and embroidered with various patterns. The Hopi type has a vertical band in black, red, and green up and down the two short sides. A special Zuñi type has a wide border similar to the mantle, with terraced top and colored medallions. It is worn by the Salimapiya. Other kilts have designs and borders which vary according to pueblo and impersonation.

In the earlier days a few of the women's woolen dresses were embroidered. The Zuñi used a deep blue woolen yarn in identical designs on the upper and lower borders,[143] and at Acoma they embroidered similar borders in color.[144]

Most of the embroidery for the Pueblos is done by the Hopi men, who are also the weavers. Special orders are filled for the priests of other pueblos who want mantles or kilts for their ceremonies. "Hopi embroidery—an art practiced only by men—is governed by very rigid rules."[145] The patterns are traditional and can be easily recognized on any dancer.

During the process of embroidery the cloth is stretched on a frame made of sticks with pointed ends.[146] The pattern is never indicated on the cloth, but is built up by counting threads. The material is folded for a center line and the border is worked in each direction so that it will come out even.

In early days, bone awls were used to poke the yarn through the cloth;

now, steel darning needles have taken their place. A simple back stitch is used, leaving much thread on the right side and picking up only a few threads on the under side. The white meander lines are made by carrying the yarn under certain threads, leaving their natural white exposed.

Colored designs are incorporated in sash ends through the brocade weave (p1. 31). (This process was described in the section on weaving.) Limited by the warp and weft of the loom, these designs are geometric. Colors are worked into separate patterns. A characteristic diamond shape in the center of the panel is made up of a border and triangular sections. Above and below run bands of black, green, and blue, with white figures picked out in the basic weave.

In the anklet another decorative effect is achieved. An oblong piece of deerskin or leather is slit internally in narrow lengthwise strips, leaving the ends uncut. These strips are wound with colored wools in geometric patterns (pl. 24). Porcupine quills and horsehair create a similar pattern. The quills, with points cut off, are moistened to make them pliable. Slit or flattened by drawing between the teeth or over the thumbnail, they are folded around the leather strip and caught by a series of half hitches in the horsehair (pl. 8).[147] Today they are sewn in place by stitches through the center of the strip. When stained with soft bright colors from berries, roots, and flowers,[148] porcupine quills make exquisite designs with a mosaiclike quality. This is a method of decoration employed by the Plains Indians. It is probable that the Pueblos acquired the technique from them.