8

Story Films Become the Dominant Product: 1903-1904

The shift to story films at the Edison Manufacturing Company was a gradual, but uneven, process that began in 1902 and proceeded in fits and starts through late 1904. By the conclusion of that year, this type of picture had clearly become the dominant product, both for Edison and throughout the motion picture industry. It was a development occurring on different levels. By the second half of 1903, Edison's "duping" of foreign pictures clearly privileged story films. As might be expected, this corresponded to the embracing of fictional headline attractions by most vaudeville exhibition services. Not until the later part of 1904, however, did Edison personnel focus the bulk of their own production efforts in this area. Between January 1903 and October 1904 output of staged/ acted films remained irregular, as the Edison Company sought to avoid undue negative costs and was thwarted by legal and personnel problems. Ambitious, commercially successful story films were made, yet they were usually followed by much more modest productions, if not an outright hiatus in filmmaking.

Disruptions

The completion of Life of an American Fireman coincided with important changes within Edison's Kinetograph Department. On February 5, 1903, James White left for Europe to become Edison's new European sales manager.[1] White's new position was important for Edison's phonograph and film businesses, and William Gilmore was not sure whether he could handle the responsibility. As he wrote Thomas Edison from Europe shortly after White had taken the job:

It would seem to me that the proper way to take hold of things here is to have one good man to look after the business in the different countries as a whole the same as I do in America but the point is who is the man. I am not prepared to say that White is big enough to swing it. I hardly think he has the experience necessary. Then again I find that he lacks nerve, which to my mind is very essential. However, as we have given him the opportunity I suppose we must let him go for the present.[2]

Gilmore also felt that White required close supervision to curtail his more impulsive schemes.[3] White's charm and entrepreneurial spirit were better suited to a producer or salesman than a ledger-conscious manager.

White's position as head of the Kinetograph Department was filled by William H. Markgraf, another of Gilmore's brothers-in-law, who had been working elsewhere in the Edison Manufacturing Company. Although he had obtained his job through nepotism, the new department manager did not receive a percentage of film sales as had James White. Nevertheless, his $30 weekly salary was raised on January 1st to $40—twice Porter's. Markgraf acted as a middle-level executive—a member of the new middle class—whereas White had functioned as a quasi-independent entrepreneur under the umbrella of Edison's corporation. Markgraf's hiring introduced a differentiation in managerial function. The department head was no longer a film producer, salesman, cameraman, and film actor. He oversaw production activities, but did not participate directly in them. Yet this was not management as Frederick Taylor envisioned it. Markgraf lacked the expertise to challenge or even guide his staff's working methods. This left Porter more firmly in control of production, since he alone had the requisite knowledge and experience.

As the Kinetograph Department was preparing Life of an American Fireman for release, Edison suffered two judicial defeats that affected company sales of films and projecting kinetoscopes. Although both setbacks were eventually reversed on appeal, at the time they were highly disruptive, bringing into question the company's future within the industry. The first involved Thomas Armat, who, through the Animated Photo Projecting Company and its successor, the Armat Moving-Picture Company, had sued the American Mutoscope Company for infringement of his projection patents. He brought suit on the last day of 1898 and, after considerable delay, won a circuit court decision favoring his patent in October 1902.[4] Reluctant to have either the patent's scope or his ownership tested in a higher court, Armat came to an agreement with Biograph. Biograph agreed to recognize the patent if he "would not insist upon the payment of the license fees . . . until the Armat Company had secured a permanent injunction against the Edison Company."[5]

In November Armat sued the Edison Company. A preliminary injunction was filed on January 19th, prohibiting the company from selling projectors. Edison lawyers appealed for a stay, and the injunction was vacated a week later. The reprieve occurred primarily because Armat's control of the patent was in doubt

owing to his earlier conflicts with Jenkins.[6] Nonetheless, the Edison Company was threatened with substantial damages and a realignment of the American motion picture industry around Armat. Armat, still anxious to avoid further testing of his patents, renewed his suggestion for a combination involving Edison, Biograph, and the Armat Moving Picture Company. In a letter to Gilmore, he pressed his case, pointing out that "the Armat Moving Picture Company has never sold a machine , therefore any monopoly that may be built up under its patents is absolutely intact ."[7] He attempted to play on the Edison Company's concurrent difficulties with Lubin by suggesting that "in fighting us you are in effect fighting for Lubin and the others who have contributed nothing to this art, and if you succeed in defeating us, you will throw this country open to the kind of competition that obtains in Europe, where the biggest fakir, such as Lubin, makes the money at the expense of legitimate business." Edison's lawyers, unmoved by Armat's anti-Semitic appeal, decided to await the outcome of the suit. Armat, however, chose not to pursue it. In June 1903 the Edison Company altered its projecting kinetoscope, replacing its one-third shutter with a half-shutter. The new shutter allowed less light to be projected through the film and onto the screen, but seemed to protect the company from any future outcome of the suit, since Armat's patent had been poorly worded.[8] Notwithstanding these commercial disruptions and slight curtailment in the projector's quality, sales of projecting kinetoscopes for the 1903 business year increased less than 10 percent over the preceding year—to $36,651 with profits of $15,637.

The second decision involved the Lubin copyright case and directly affected Edison film production. On January 22d, one day after Life of an American Fireman had been copyrighted, Judge George Mifflin Dallas ruled that Edison's method of copyrighting motion pictures was unacceptable. Since 1897 Thomas Edison (via his secretary) had been sending paper prints of his company's films to the Library of Congress, where each was duly copyrighted as a single photograph. Edison lawyers argued that this procedure was adequate: "Each view is not sold by itself, but are sold in numbers together, being printed on one strip of film for the foregoing purpose (of showing successive views of the same object that give the appearance of actual motion) and constituting one photograph."[9] Lubin denied that "such photographic representations constitute one photograph and that the same can be copyrighted as one photograph or protected by a single copyright and avers that such photographic films are the result of joining together distinct and independent photographic exposures each requiring a separate copyright for securing an exclusive right to such original intellectual conception as it may contain."[10] Judge Dallas agreed with Lubin, ruling that:

It is requisite that every photograph, no matter how or for what purpose it may be cojoined with others, shall be separately registered, and that the prescribed notice of copyright shall be inscribed upon each of them. It may be true, as has been argued, that this construction of the section renders it unavailable for the protection of such a series

of photographs as this; but if, for this reason, the law is defective, it should be altered by Congress, not strained by the courts.[11]

Edison appealed.

Edison executives, while waiting for a review, drastically curtailed their company's output of original subjects, anticipating that these would be copied by Lubin and other "infringers." Little or nothing was produced at the Edison studio over the next three months, although a few new films taken by Abadie in Europe were offered for sale. A small fire ravaged the Kinteograph Department's darkroom on February 9th, injuring William Jamison and further disrupting production. The company's February and particularly its May catalogs featured dupes of foreign productions: Méliès' Joan of Arc, Robinson Crusoe , and Gulliver's Travels ; Urban Trading Company news films of the Durbar celebrations in Delhi, India; Pathé's Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves as well as Williamson and G. A. Smith pictures.[12]

Deeply concerned with the many legal problems that threatened the future of his enterprises, Edison had his principal patents lawyer, Frank Dyer, move into his laboratory on April 1, 1903.[13] Soon after, Edison's legal fortunes in the motion picture field were revived. On April 21st, in a landmark decision, Judge Dallas's ruling was reversed by the U.S. court of appeals. Judge Joseph Buffington, writing the opinion, asserted that:

The instantaneous and continuous operation of the camera is such that the difference between successive pictures is not distinguishable by the eye and is so slight that the casual observer will take a very considerable number of successive pictures of the series, and say they are identical . . . To require each of numerous undistinguishable pictures to be individually copyrighted, as suggested by the court, would in effect be to require copyright of many pictures to protect a single one.

When Congress in recognition of the photographic art saw fit in 1865 to amend the Act of 1831 (13 Stat 540), and extend copyright protection to a photograph or negative, it is not to be presumed it thought such art could not progress and that no protection was to be afforded such progress. It must have recognized there would be change and advance in making photographs just as there have been in making books, printing chromos and other subjects of copyright protection."[14]

A year after bringing his copyright suit against Lubin, Edison had finally won. Although films had been copyrighted in Edison's name for six years, the threat of legal action had always been enough to intimidate potential dupers less determined than Lubin.[15] Judge Buffington's decision was the first actually to recognize the validity of Edison's method of copyright. If the court had done otherwise, it would have discouraged American motion picture production still further. Howard Hayes, Edison's lawyer for the case, greeted the decision with enthusiasm. "It is a strong one and will be followed I think in other courts," he

wrote Gilmore. "Now that copyrighting the films has become of importance I want to arrange a plan by which the copyrighting can be done correctly and evidence of it kept so that it will be available in any suit on a moments notice."[16] As a result of Hayes' directive, copyright files were subsequently kept at West Orange; today they provide the historian with essential information about most Edison productions.[17]

The series of legal battles and injunctions between 1901 and April 1903 left the American industry in shambles. Uncertainties had discouraged investment in plant and negatives. Although Biograph had won its court case against Edison in March 1902, it remained a weakened competitor during the following year. The subjects and representational practices for its large-format service were increasingly antiquated. A typical program relied on a miscellaneous collection of short actualities with a few trick films and comedies thrown in for relief.[18] In contrast, Vitagraph had recognized the value of "headline attractions all of which are long subjects lasting from 10 to 20 minutes each."[19] This enabled Vitagraph to take over the Keith circuit from Biograph during the first week of April. Afterwards one trade journal observed that the new Vitagraph program was "the best series of films seen here in many weeks."[20] George Spoor's Chicago-based exhibition service made a similar shift toward story films, a key element in the reviving popularity of vaudeville film programs.

Edison, Vitagraph, Lubin, Spoor, and Selig—all relied heavily on European imports. Like Edison, many took local, inexpensive films that could not be provided by European producers. To a remarkable degree, Edison's competition with its rivals revolved around the rapidity with which newly released European story films could be brought to the United States, duped, and sold. The original prints that Edison acquired for these purposes were then purchased by Waters' Kinetograph Company, while dupes were marketed to other exhibitors. An urgent telegram from Gilmore to White in England underscored the importance of this business practice:

White: Vitagraph Co. getting foreign films ahead of us. They have received poachers, deserters, falling chimney and others at least ten days ahead of us. This very embarrassing. Unless can have your assurance that arrangements can be made for immediate shipments will send someone to take charge this end of the business. . . . Gilmore.[21]

Edison executives had adopted a business strategy that largely ignored the production capabilities of its film department. By duping foreign films on a massive scale, the department could limit its investment primarily to the cost of negative stock.

The easy money Edison and other American producers had been making from dupes was threatened in March 1903, when Gaston Méliès arrived in the United States to represent his brother Georges. In June he opened a New York office and factory to print and distribute Méliès' "Star" films and to secure the

economic benefits for their creator. His first catalog chided American manufacturers, announcing

GEORGE MELIES , proprietor and manager of the Théâtre Robert-Houdin, Paris, is the originator of the class of cinematograph films which are made from artificially arranged scenes, the creation of which has given new life to the trade at a time when it was dying out. He conceived the idea of portraying comical, magical and mystical views, and his creations have been imitated without success ever since.[22]

He also announced, "we are prepared and determined energetically to pursue all counterfeiters and pirates. We will not speak twice, we will act." Star films were then considered "the acme of life motion photography,"[23] and Georges Méliès was using a double camera to take two negatives of each subject, shipping one to New York. Henceforth, these were copyrighted, putting an end to the duping of future Star films.[24] Edison and other American companies found different makes to dupe, but they now had to face competition in the domestic market from the world's foremost manufacturer.

Production Resumes at Edison

When Edison filmmaking resumed in late April, the Kinetograph Department's organization and personnel had substantially changed. Not only was Markgraf the new manager, but Arthur White and George S. Fleming had left in early April. Fleming was promptly replaced by William Martinetti, a scenic painter who earned $20 per week—the same sum as Porter. With these disruptions, film sales for the 1903-4 business year advanced 20 percent to $91,122—a modest increase given the general industrywide revival and the impact of Great Train Robbery sales late that business year. Production and related film costs, moreover, increased still faster, and film profits fell 13 percent to $24,813.

Although Edison ads ballyhooed Life of an American Fireman , nothing of equal ambition was immediately undertaken. The next sixty-two copyrighted Edison films were brief scenes made for the exhibitor-dominated cinema. Most were part of the popular travel genre. Twelve had been shot by James White in the West Indies during his December 1902 honeymoon (Native Women Coaling a Ship and Scrambling for Money ). With White's arrival in Europe, Abadie was free to tour the Mediterranean basin with his camera. He started out at the Grand Carnival in Nice (Battle of Confetti at the Nice Carnival ); traveled to Syria, Palestine (A Jewish Dance at Jerusalem ) and Egypt (Excavating Scene at the Pyramids of Sakkarah ); then went through Italy, Switzerland, and Paris before reaching England on May 10th. Abadie then returned to the United States, where his films were developed and thirty-four submitted for copyright.

Edison's New York-based cameramen resumed production on April 29th, eight days after Judge Buffington's decision. Over the next two weeks, Edwin

Documenting "the other half": New York City "Ghetto" Fish Market.

Porter and James Smith shot at least fifteen travelogue-type subjects in and around Manhattan. The series included panoramas of the skyline; staged activities by the fire department, police, and harbor patrol (New York Harbor Police Boat Patrol Capturing Pirates ); parades (White Wings on Review ), and scenes of New York's underbelly (New York City Dumping Wharf ). For New York City "Ghetto" Fish Market , Smith placed his camera at a window or on a low rooftop. Looking down on an open air market, it panned along the street as one or two individuals in the crowd stared into its lens.[25] Soon afterwards, Porter stopped off in Sayre, Pennsylvania, and took Lehigh Valley Black Diamond Express , a replacement negative of that still popular subject, on May 13th. Perhaps the cameraman was on a visit to Connellsville; in any case, he had returned to New York City by May 30th, Decoration Day, when he filmed Sixty-Ninth Regiment, N.G.N.Y . as the unit marched up Fifth Avenue. Three weeks later he photographed Africander Winning the Suburban Handicap . Such subjects had been taken for the past six years and had become routine.

Méliès' entry into the American market and the resolution of various court suits encouraged U.S. film companies to produce more ambitious films with American locales and subject matter. If Jack and the Beanstalk and Life of an American Fireman were part of nonspecific urban/industrial genres found in all major producing countries, American story films made in the second half of 1903 tended to be more nationalistic. Biograph's first dramatic headliners, Kit

Carson and The Pioneers , as well as Edison's Uncle Tom's Cabin, Rube and Mandy at Coney Island , and The Great Train Robbery , all used American myths and entertainments as a source.[26] Certainly this made sense, since less nation-specific pictures could be acquired from overseas.

Uncle Tom's Cabin

Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-slavery and anti-capitalistic novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1851) remained immensely popular throughout the North as an affirmation and retrospective justification of the Civil War. Its spectacular story, more than its political content, was kept alive by theatrical adaptations that numerous acting troupes performed in America's opera houses.[27] When the Kinetograph Department returned to production during spring 1903, it arranged for one of these itinerant companies to stage the play's highlights in the Edison studio. This decision may have been influenced by Biograph's May release of Rip Van Winkle , a 200-foot compendium of scenes from the Rip Van Winkle play, showing "the various events beginning with Rip's departure for the mountains and ending with his awakening from his 20 years' sleep."[28] Porter's Uncle Tom's Cabin , which totaled 1,100 feet, was much more ambitious. The play was condensed rather than excerpted. A race between the steamboats Natchez and Robert E. Lee was done in miniature, and a few effects, like the double exposure used to show Eva's ascent to heaven, were reworked to take advantage of the motion picture camera's capabilities.

Porter's Uncle Tom's Cabin has often been criticized for its lack of "cinematic" qualities and viewed as a disappointing regression after Life of an American Fireman .[29] Such criticism feels the absence of a coherent spatial/temporal world as an absolute loss. It valorizes narrowly progressive tendencies in Porter's work, isolating filmic strategies felt to have contributed to the development of Hollywood cinema. While Uncle Tom's Cabin does not fit into a simple linear pattern of development from Life of an American Fireman to The Great Train Robbery , it does represent a sustained exploration of the filmed theater genre that remained an important aspect of Porter's filmmaking career—whether Parsifal (1904), The Devil (1908), or James O'Neill in The Count of Monte Cristo (1912).

A relatively unadulterated record of nineteenth-century theater, Uncle Tom's Cabin displays the presentational elements of this practice that exerted often determining influences on the screen: acting techniques (codified gesture, the playing to an audience), spatial construction (set design, the use of frontal compositions, the maintenance of a proscenium arch), and a nonrealistic, but highly serviceable, temporality. For traveling theater companies, portable sets had to suggest or symbolically represent the locale for a drama. Since changing scenery was difficult, action that moved to a different locale generally had to wait until

Uncle Tom's Cabin. Eliza escapes while Uncle Tom is sold into slavery.

the completion of subsequent actions in the current scene before it could be played out.

The same time frame is shown successively in the last two scenes of Uncle Tom's Cabin . In scene 13, Uncle Tom is beaten on the veranda by Simon Legree's minions and then carried off; George Shelby, Jr., arrives to buy back Tom, then leaves in search of him; and finally Marks—an officer of the law and symbol of the state—kills Legree to revenge the death of Uncle Tom . As the final scene begins, Uncle Tom is still alive in the woodshed and George Shelby, Jr., arrives in time to witness his death. Although Tom's death is shown last, the intertitles and action clearly suggest that it precedes the killing of Legree. Temporality, as in the closing scenes of Life of an American Fireman , is manipulated for emotional and thematic purposes determined in part by a religious interpretation of events. This reordering of events, which violates the linear logic of later narrative cinema, can easily appear naive or inept to modern audiences. For turn-of-the-century audiences, it allowed the emotional highpoint, the death of Uncle Tom, to come last where it belonged.

Viewing the film today, audiences are faced with fundamental problems of comprehension—identifying characters and following narrative development. At the turn of the century, however, the story was part of American folklore and native-born Americans were as familiar with the melodramatic incidents portrayed on the screen as with the mechanics of a fire rescue. As with Jack and the Beanstalk or most news films, the narrative was not presented as if the audience was seeing it for the first time, but existed in reference to a story assumed to be already present in the audience's mind.[30]

Porter's Uncle Tom's Cabin reveals its reliance on audiences' preexisting knowledge in various ways. Following the example of G. A. Smith's Dorothy's Dream , each scene is introduced by a title that does not explain the next scene

but labels it to prime the viewer's preexisting knowledge.[31] General familiarity with the narrative was reflected in most Edison ads and promotional materials, which simply listed the scenes, as if that would adequately define their contents. Even the reprinted description assumed that the reader already knew the various characters. Uncle Tom's Cabin was a ritual reiteration of a common heritage and could trigger deeply felt emotions that audiences already associated with the narrative. But even allowing for this a priori knowledge, the exhibitor could still use a lecture to help audiences follow the on-screen narrative and identify characters whose dress sometimes changed from one scene to the next. For immigrants and those otherwise unfamiliar with the film's frame of reference, additional cues must have been essential.[32]

Uncle Tom's Cabin was heralded by George Kleine as "the most elaborate effort at telling a story in moving pictures yet attempted," and subsequently described as "the largest and most expensive picture yet made in America."[33] By employing an established Uncle Tom's Cabin theatrical company, Porter made a film that looked expensive yet required much less investment than a truly "original" production like Jack and the Beanstalk . Certainly its scale did not intimidate Edison's competitor Sigmund Lubin, who immediately remade it.

Lubin had reacted to Edison's victory in the copyright case with his customary flair: he copyrighted over thirty popular titles without bothering to make the films. These included Three Little Pigs, Old Mother Hubbard , and Jack and Jill .[34] Hearing that Edison intended to film Uncle Tom's Cabin , Lubin copyrighted that title as well, a fact that was shared with customers. As the traveling exhibitor N. Dushane Cloward, informed the Orange laboratory:

While in Lubin's Philada. office yesterday one of his assistants volunteered some information regarding a matter in which I know you people are interested.

It may not be a fact or it may not be news to you or if both it may be of no importance but i [sic ] feel that the statement passed on to you would be of no injustice to Lubin and may be of guidance to you. The conversation was on new film subjects. The party asked me how Edison people were getting along with U/T/Cabin. I having told him that I had been dealing with Edison. I replied that I had heard some talk of the subject being prepared last Spring but knew nothing of it whatever. The representative remarked that Lubin had a copyright for the title of Uncle Tom's Cabin in motion pictures and had it several years.[35]

Cloward's information delayed the film's release from late July to early September while Edison's lawyer investigated. "I learned that Sigmund Lubin has copyrighted a photograph under the title 'Uncle Tom's Cabin' on May 1st 1903," Howard Hayes reported, after consulting the Library of Congress. "That copyright, however, does not give him a monopoly on the title. The copyright applies to the picture itself, regardless of the title, so, unless you copy his picture, he cannot interfere with the use of the title."[36] The following week, Edison

finally advertised its film in the trades. The week after, Lubin announced the imminent release of his Uncle Tom's Cabin .[37]

Edison executives thought Lubin might try to sell their film on the basis of his earlier copyright. Lubin, in fact, simply waited for the picture's release before making his own meticulous imitation. By dropping a cakewalk sequence, increasing the pacing and filming at fewer frames per second, Lubin reduced the length of his version from 1,100 feet to 700 feet. His brochures for the film even lifted entire descriptions from the Edison catalog.[38] With Lubin's pictures underselling Edison's by a penny per foot, his Uncle Tom's Cabin offered substantial savings to exhibitors.

Summer Fun

Following the solemnity of Uncle Tom's Cabin , most Edison productions taken during the summer months involved elements of play. Both before and behind the camera, the spirit of Coney Island frequently prevailed.[39]Little Lillian, Toe Danseuse brought "the youngest premiere danseuse in the world" before the camera and made skillful use of stop-action photography to combine four separate dances into one continuous "shot," with "her beautiful costume changing mysteriously after each dance."[40]Subbubs Surprises the Burglar , the first of several comedies made in rapid succession, was shot on July 16th. Featuring a popular cartoon character, this single-shot film otherwise imitated Biograph's The Burglar-Proof Bed (shot June 27, 1900). When a burglar enters Subhubs' bedroom, "The man awakes and pulls a lever, closing himself up in the folding bed, the bottom of which is iron-clad, with guns and portholes. The burglar is dumbfounded, and cannot move. Subhubs turns his battery loose, blowing the burglar to pieces. He then raises an American flag on a staff on top of the bed as a signal of victory. The bed opens up again and Subhubs goes to sleep."[41] In Street Car Chivalry , an attractive young lady is offered a seat by every man in the trolley. A stout woman with an arm full of bundles, however, is ignored until she loses her balance and collapses on top of a "dude." The narrow limits of male gentility are spoofed, and the different ways each woman claims a seat provide comic repetition. The film was sufficiently popular for Lubin to remake it that fall.[42]

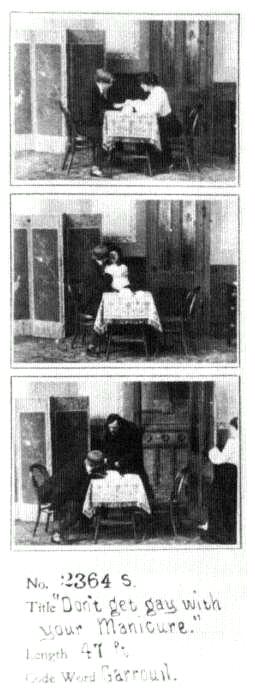

The Gay Shoe Clerk , a brief comedy shot on July 23d, was inspired by at least two films: either Biograph's Don't Get Gay with Your Manicure or No Liberties, Please[43] (shot July 10, 1902) and G. A. Smith's As Seen Through a Telescope , which Edison distributed as The Professor and His Field Glass :

NO LIBERTIES, PLEASE.

A young man in a manicure parlor attempts to kiss the pretty attendant but has his ears soundly boxed for his trouble.[44]

THE PROFESSOR AND HIS FIELD GLASS.

An old gentleman is shown on a village street, looking for something through a field glass. Suddenly, he levels the glass on a young couple coming up the road. The girl's shoe string came loose, and her companion volunteers to tie it. Here the scene changes, showing how it looks through the old man's glass. A very pretty ankle at short range. Scene changes back again and shows the old fellow tickled to death over the sight. The couple, who, by the way, caught "Peeping Tom," come toward him, and as the young man passes behind him, he knocks off his hat and kicks the stool on which he is sitting, from under him, making the old chap present a rather ludicrous appearance, as he sits in the street. Length 65 feet.[45]

THE GAY SHOE-CLERK.

Scene shows interior of shoe-store. Young lady and chaperone enter. While a fresh young clerk is trying a pair of high-heeled slippers on the young lady, the chaperone seats herself and gets interested in a paper. The scene changes to a very close view, showing only the lady's foot and the clerk's hands tying the slipper. As her dress is slightly raised, showing a shapely ankle, the clerk's hands become very nervous, making it difficult for him to tie the slipper. The picture changes back to former scene. The clerk makes rapid progress with his fair customer, and while he is in the act of kissing her the chaperone looks up from her paper, and proceeds to beat the clerk with an umbrella. He falls backward off the stool. Then she takes the young lady by the arm, and leads her from the store. Length 75 feet.[46]

Porter's film inverts one gender position in the Biograph narrative (in which the manicurist's lover-husband boxes the man's ears). Likewise, it dispenses with Smith's matte and explicit point-of-view motivation but keeps the "very close view" of the woman's ankle. It is the man behind the camera (and presumably the male viewer) instead of the man behind the telescope whose attention is focused on the woman's ankle, motivating the cut to a closer view. Such simple shifts and recombinations suggest the variations that frequently characterized "originality" in this period.

The Gay Shoe Clerk valorizes the spectator's position in a manner that recalls What Demoralized the Barbershop (1897). True, the young man not only sees but touches and even kisses the young lady, but his transgression is promptly greeted by a bash on the head from the chaperone. Meanwhile, the male spectator enjoys the woman's ankle and the shoe clerk's chastisement. In fact, both pictures suggest that cinema, by removing the spectator's physical presence from the scene, allows the (male) viewer to take pleasure in what is otherwise forbidden. The close view of the young lady's ankle is shown against a plain background to further focus the viewer's attention, suggesting the subjective nature of the shot and abstracting it from the scene. Not only does this second shot have a different background, but the female customer probably had a stand-in. Her dress, at least, is different: the far shot does not reveal the white petticoats, which are prominently displayed in the closer view. Porter and other

The Gay Shoe Clerk. The cut from a very close view back to establishing shot.

early filmmakers obviously anticipated the editorial principles of the artificial woman articulated by Lev Kuleshov.[47] The ankle is also isolated in an abstracted space. While Porter seems to have been concerned with matching action, the cut did not involve a seamless "move in" through a spatially continuous world but functioned within a syncretic representational system.[48]

Playfulness was plentiful at the Edison studio. Thinking up skits and pulling them off was fun even if work weeks were long. One can imagine Abadie's leg—or that of some other assistant—filling the young lady's stocking in The Gay Shoe Clerk . Tasks were manageable and varied. The integration of work and play was particularly evident during August, when the cameramen chose activities that took them to resort areas and the seashore. Informal supervision and the quotidian nature of many films enabled these employees to sneak away from the hot city and relax.

On several occasions, Edison personnel took their cameras to Coney Island, where they produced actualities such as Shooting the Rapids at Luna Park and Rattan Slide and General View of Luna Park .[49] There, Porter made the "headliner" copyrighted as Rube and Mandy at Coney Island , but listed in Edison's catalog under a slightly different title:

RUBE AND MANDY'S VISIT TO CONEY ISLAND.

The first scene shows this country couple entering Steeplechase Park. They proceed to amuse themselves on the steeplechase, rope bridge, riding the bulls and the "Down and Out." The scene then changes to a panorama of Luna Park, and we find Rube and Mandy doing stunts on the rattan slide, riding on the miniature railway, shooting the chutes, riding the boats in the old mill, and visiting Professor Wormwood's Monkey theatre. They next appear on the Bowery, where we find them with the fortune tellers, striking the punching machine and winding up with the frankfurter man. The climax shows a bust view of Rube and Mandy eating frankfurters. Interesting not only for its humorous features, but also for its excellent views of Coney Island and Luna Park. Length 725 feet.[50]

Rube and Mandy at Coney Island can be compared to exhibitor-constructed programs of the period that combined travel views or scenics with short comedies—a programming idea suggested by William Selig. One can imagine a program on Coney Island consisting of Shooting the Rapids at Luna Park and similar films, but laced with studio comics for variety.[51] Working within such a syncretic framework, Porter integrated comedy and scenery, maintaining a consistent tone from one shot to the next even as he perpetuated this dichotomy within the individual shots.

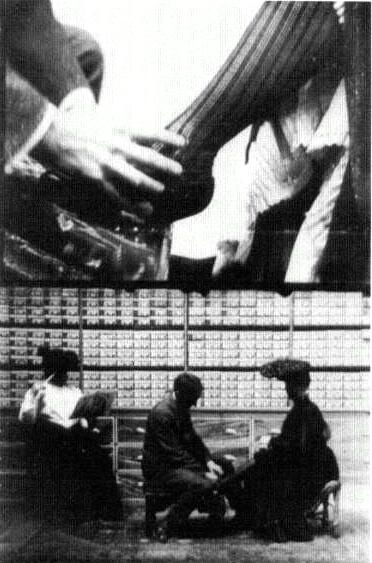

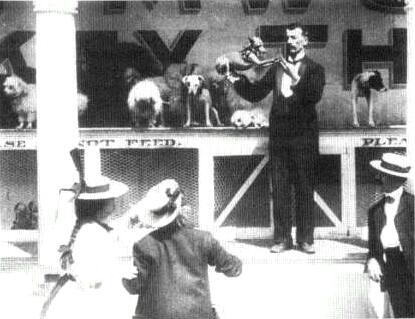

In Rube and Mandy at Coney Island , two country bumpkins experience the marvels of New York's famous amusement park. While the vaudeville actors did their bits in stage costume with exaggerated gestures, Porter treated Coney Island for its scenic value with a highly mobile camera (five shots contain significant camera movement) still associated with actuality material. In several

We see Prof. Wormwood and his Dog and Monkey Theater over Rube

and Mandy's shoulders in Rube and Mandy at Coney Island.

scenes the performers' improvisations forced Porter to accommodate the unexpected by following the action with his camera. In another scene, the actors' movements about the amusement park enabled the camera to photograph a "circular panorama." The performers are often subservient to a scenic impulse, not only with the panorama but at Professor Wormwood's Dog and Monkey Theater, where the film viewer looks over the actors' shoulders to see the animals perform. The couple mediates the audience's experience of the amusement park and ties together a series of potentially discrete views as they move from one ride to the next. At other moments, Coney Island serves as a setting for the comedians' business. The scenes are arranged through an association of analogous situations: Rube and Mandy's arrival in an absurd carriage is followed by rides on wooden horses and a cow; "Shooting the Chutes" is followed by a ride in a love boat. Although the film has little narrative development, it achieves a degree of closure, opening with the couple's arrival and ending with an apotheosis-like "bust view" of the two eating a hot dog against a black background. This final scene repeats the preceding one while abstracting it from the Coney Island setting and reducing it to a "facial expression" shot.

Porter spent mid August in the popular seaside resort of Atlantic City, mak-

ing at least one film during his working vacation. Seashore Frolics , staged using cooperative vacationers, ends with a persistent still photographer (Porter's assistant?) being dumped into the ocean by good-natured bathers. The cameraman closed his summer season of filming at the New York Caledonian Club's 47th annual festival of sports on Labor Day.

That August, A. C. Abadie was at Coney Island (Orphans in the Surf and Baby Class at Lunch ), then retreated to Wilmington, where he filmed outdoor scenes for N. Dushane Cloward. Cloward, a traveling exhibitor who played churches and noncommercial venues during the theatrical season, opened a motion picture show in Brandywine Springs Park for the summer of 1903.[52] He arranged with the Edison Company to take local views that would attract patrons to his theater. Cloward had Abadie photograph a baby review and a Maypole dance on August 21st.[53] Together they organized the filming of Turning the Tables and Tub Race at the local swimming hole. In the former, a policeman tries to chase a group of boys out of a forbidden swimming hole, but finds himself pushed into the water instead. The naughty boys break the law; but the law, rather than the boys, has to pay.

Cameraman J. B. Smith, although principally confined to the Orange laboratory, where he remained in charge of print production, spent part of August photographing the America's Cup races between the Reliance and Sir Thomas Lipton's Shamrock III . This news event, however, was not given the amount of attention it had received two years earlier. Only three films were offered for sale: two covered the start and finish of the first race on August 22d. The third film, taken midway through the second race, was not considered worth copyrighting. The films were offered as individual topicals rather than a complete series worthy of headliner status.

The Porter-Abadie-Smith trio continued to be the responsible photographers during the fall. After Labor Day, Porter returned to his New York base, where he filmed Eastside Urchins Bathing in a Fountain and New York City Public Bath as part of his continuing documentation of the city's ghetto life. In a sweeping panorama, the 150-foot Tompkins Square Play Grounds documents a supervised playground with basketball and boys forming a human pyramid for the camera. Porter followed his Lower Eastside shoots with various short com-edies. Two Chappies in a Box is set in a vaudeville theater, where two male spectators respond to a female performer on the stage. For today's viewer, the humor comes from a simple psychoanalytic reading. A phallic wine bottle stands between the two men on the railing of their box, and they become so excited over the woman's singing that they spill the contents and ruin the draperies. For this offense they are quickly expelled. As with many of these short comedies, an obscene joke lurks just below the surface of a film that seems to be teaching a moral lesson—that rowdy behavior will not be tolerated. Between such minor comedies, Porter filmed The Physical Culture Girl , a vaudeville-type turn that

Two Chappies in a Box.

featured the recent winner of the Physical Culture Show at Madison Square Garden. Two months earlier, Biograph had made a similar subject with the same title. Porter's Heavenly Twins at Lunch and Heavenly Twins at Odds , of baby twins, appealed to Americans' love for small children (the New York Journal , for instance, consistently ran pictures of babies, playing to its readers' sentiments).

Smith spent most of the fall working as a foreman at the West Orange film plant, while Abadie traveled along the East coast taking films of floods, fire ruins, parades, and the Princeton-Yale football game. Like Porter, they were expected to perform multiple tasks. Abadie, in particular, functioned as a roving cameraman sent on special assignment (i.e., the cameraman system). Many of these short Edison films, particularly the topicals, were done in a perfunctory fashion, perhaps because similar subject matter had been shot so frequently. After seeing films of the Galveston disaster in 1900, audiences might be expected to find Flood Scene in Paterson, N.J ., photographed by Abadie in mid October, somewhat anticlimactic. The law of diminishing returns seemed to operate and Markgraf, like other American film executives, failed to mobilize his cameramen to mount the elaborate and timely coverage that might have kept alive White's

vision of a visual newspaper. Interest was shifting to the cinema's capacity as a storytelling form. This was particularly apparent at Biograph.

In March 1903, after losing the Keith theaters as an exhibition outlet, the Biograph Company reassessed its business strategies and placed new emphasis on fictional narratives. By June, Biograph had opened an indoor film studio with electric lighting at its newly acquired offices on Fourteenth Street.[54] If the Edison Company's glass-enclosed studio had had advantages over Biograph's old rooftop facility at 841 Broadway, the competitive edge returned to Biograph, since filming was no longer affected by weather and winter hours. In the months immediately following the studio's completion, Biograph cameramen shot many multishot fictional subjects. Most were not offered immediately for sale but used as exclusive headliners for Biograph's revived exhibition service. Biograph's resurgence in production and its commitment to a 35mm format revived the company's fortunes. By August, Biograph had regained its position on the Keith circuit and was again competing seriously with Edison.

The move toward story films had accelerated by the latter half of 1903. Lubin made Ten Nights in a Bar-Room (700 feet) in October.[55] Although fairy-tale films like Méliès' Fairyland and Hepworth's Alice in Wonderland continued to be popular, English story films depicting crimes and violence began to appear and found receptive audiences. Sheffield Photo's A Daring Daylight Burglary , British Gaumont/Walter Haggar's Desperate Poaching Affray and R. W. Paul's Trailed by Bloodhounds were duped and sold by Edison, Biograph, and Lubin between June and October 1903.[56] Such films provided inspiration and competitive pressures that help to explain the production of Porter's most famous subject, The Great Train Robbery .

The Great Train Robbery

In late October, Porter began working with a young actor, Max Aronson. Earlier that month, the thespian had toured with Mary Emerson's road company of His Majesty and the Maid .[57] The engagement did not work out, and he returned to New York in need of employment. After changing his name to George M. Anderson, Aronson found work at the Edison studio, thinking up gags (Buster's Joke on Papa , shot October 23d) and appearing in pictures (What Happened in the Tunnel , photographed on October 30th and 31st). Porter continued to collaborate with Anderson on numerous subjects over the next several months, including The Great Train Robbery .

The Great Train Robbery was photographed at Edison's New York studio and in New Jersey at Essex County Park (the bandits cross a stream at Thistle Mill Ford in the South Mountain Reservation) and along the Lackawanna railway during November 1903.[58] Justus D. Barnes played the head bandit; Anderson the slain passenger, the tenderfoot dancing to gunshots, and one of the robbers; and Walter Cameron the sheriff. Many of the extras were Edison em-

ployees. Most of the Kinetograph Department's staff contributed to the picture: J. Blair Smith was one of the photographers and Anderson may have assisted with the direction.[59]

The film was first announced to the public in early November 1903 as a "highly sensationalized Headliner" that would be ready for distribution early that month.[60] Since the Edison Manufacturing Company urged exhibitors to order in advance and the film was not ready until early December, the delay probably explains why the Kinetograph Department submitted a rough cut of the film for copyright purposes. It avoided distribution snags once the release prints were available. The paper print version of the film, copyrighted by the Library of Congress, is longer than the final release print by about fifteen feet. Over the years, surviving copies of the film have been duped and offered for sale. Although a few have suffered extensive alteration, most have their integrity fundamentally intact. One of the most interesting versions was hand tinted.[61]

The Great Train Robbery had its debut at Huber's Museum, where Waters' Kinetograph Company had an exhibition contract. The following week it was shown at eleven theaters in and around New York City—including the Eden Musee.[62] Its commercial success was unprecedented and so remarkable that contemporary critics still tend to account for the picture's historical significance largely in terms of its commercial success and its impact on future fictional narratives. Kenneth Macgowan attributes this success to the fact that The Great Train Robbery was "the first important western."[63] William Everson and George Fenin find it important because "it was the first dramatically creative American film, which was also to set the pattern—of crime, pursuit and retribution—for the Western film as a genre."[64] Robert Sklar, viewing the film in broader terms, accounts for much of the film's lasting popularity. He points out that Porter was "the first to unite motion picture spectacle with myth and stories about America that were shared by people throughout the world."[65] Little more has been said about Porter's representational strategies since Lewis Jacobs praised the headliner for its "excellent editing."[66] Noël Burch, André Gaudreault, and David Levy are among the few who have discussed the film's cinematic strategies with any historical specificity; their useful analyses, however, can be pushed further.[67]The Great Train Robbery is a remarkable film not simply because it was commercially successful or incorporated American myths into the repertoire of screen entertainment, but because it presents so many trends, genres, and strategies fundamental to cinematic practice at that time.

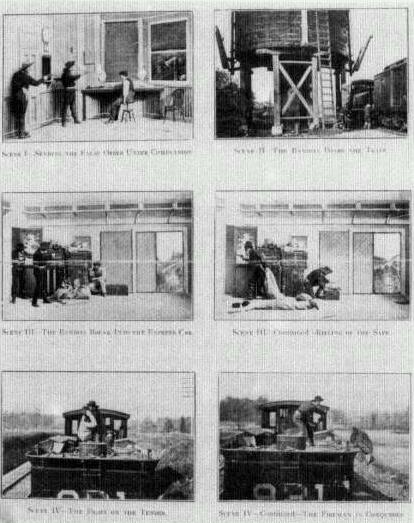

Porter's film meticulously documents a process, applying what Neil Harris calls "an operational aesthetic" to the depiction of a crime.[68] With unusual detail, it traces the exact steps of a train robbery and the means by which the bandits are tracked down and killed. The film's narrative structure, as Gaudreault notes, utilizes temporal repetition within an overall narrative progression. The robbery of the mail car (scene 3) and the fight on the tender (scene

4) occur simultaneously according to the catalog description, even though they are shown successively. This returning to an earlier moment in time to pick up another aspect of the narrative recurs again in a more extreme form, as the telegraph operator regains consciousness and alerts the posse, which departs in pursuit of the bandits. These two scenes (10 and 11) trace a second line of action, which apparently unfolds concurrently with the robbery and getaway (scenes 2 through 9), although Porter's temporal construction remains imprecise and open to interpretation by the showman's spiel or by audiences through their subjective understanding. These two separate lines of action are reunited within a brief chase scene (shot 12) and yield a resolution in the final shoot-out (shot 13).

The issue of narrative clarity and efficiency is raised by The Great Train Robbery . At one point, three separate actions are shown that occur more or less

simultaneously in scenes 3, 4, and 10. How were audiences, even those that understood the use of temporal repetition and overlap in narrative cinema, to know that scenes 3 and 4 happened simultaneously, but not scenes 1 and 2? How were they to determine the relationships between shots 1-9 and 10-11 until they had seen shot 12? There are no intertitles, and much depended on audience familiarity with other forms of popular culture where the same basic story was articulated. Scott Marble's play The Great Train Robbery , Wild West shows, and newspaper accounts of train holdups were more than sources of inspiration: they facilitated audience understanding by providing a necessary frame of reference. While The Great Train Robbery demonstrated that the screen could tell an elaborate, gripping story, it also defined the limits of a certain kind of narrative construction.

The common belief that The Great Train Robbery was an isolated breakthrough is inaccurate. While Porter was making his now famous film, Biograph produced The Escaped Lunatic , a hit comedy in which a group of wardens chase an inmate who has escaped from a mental institution.[69] On the very day that Thomas Edison copyrighted his celebrated picture, Biograph copyrighted a 290-foot subject made by British Gaumont, Runaway Match , involving an elaborate car chase between an eloping couple and the girl's parents. Eleven days later the film was offered for sale as An Elopement a la Mode .[70]

A Daring Daylight Burglary , which the Edison Company had duped and marketed in late June, was particularly influential in creating the framework within which Porter produced The Great Train Robbery ,[71] even though American popular culture provided the specific subject matter. Edison's 1901 Stage Coach Hold-up , a film adaptation of Buffalo Bill's "Hold-up of the Deadwood Stage," served as one source. The title and initial idea for the film were suggested, however, by Scott Marble's melodrama. The New York Clipper provides a story synopsis:

A shipment of $50,000 in gold is to be made from the office of the Wells Fargo Express Co. at Kansas City, Mo., and this fact becomes known to a gang of train robbers through their secret agent who is a clerk in the employ of the company. The conspirators, learning the time when the gold is expected to arrive, plan to substitute boxes filled with lead for those which contain the precious metal. The shipment is delayed, and the lead filled boxes are thereby discovered to be dummies. This discovery leads to an innocent man being accused of the crime. Act 2 is laid in Broncho Joe's mountain saloon in Texas, where the train robbers receive accurate information regarding the gold shipment and await its arrival. The train is finally held-up at a lonely mountain station and the car blown open. The last act occurs in the robber's retreat in the Red River cañon. To this place the thieves are traced by United States marshals and troops, and a pitched battle occurs in which Cowboys and Indians also participate.[72]

The play premiered on September 20, 1896, at the Alhambra Theater in Chicago, and soon came to the New York area, where it was well received.[73]

One page of Edison's illustrated catalog for The Great Train Robbery.

The operational aesthetic at work: the film details the robbery of a train step by step.

Periodically revived thereafter, the melodrama played at Manhattan's New Star Theater in February 1902. Porter could have easily seen it on several occasions.

The Great Train Robbery was advertised as a reenactment film "posed and acted in faithful duplication of the genuine 'Hold-ups' made famous by various outlaw bands in the far West."[74] News stories of train holdups, like the ones appearing in September 1903, may have encouraged a more authentic detailing

of events (see document no. 14). Eastern holdups, also evoked in Edison ads, took place in Pennsylvania on the Reading Railroad in late November—after the film was completed. A telegraph operator was murdered and several stations held up by "a desperate gang of outlaws who are believed to have their rendezvous somewhere in the lonely mountain passes along the Shamokin Division."[75] It was hoped that such incidents would make the film of timely interest. The Great Train Robbery continued to be indebted to at least one aspect of the newspapers, the feuilletons in Sunday editions, with their highly romanticized, but supposedly true, stories of contemporary interest.

DOCUMENT NO . 14 |

KILLS HIGHWAYMAN |

Express Messenger Prevents Robbery-Bullet Wounds Engineer. |

Portland, Ore. Sept. 24.-The Atlantic Express on the Oregon Railroad and Navigation line, which left here at 8:15 o'clock last night, was held up by four masked men an hour later near Corbett station, twenty-one miles east of this city. One of the robbers was shot and killed by "Fred" Kerner, the express messenger. "Ollie" Barrett, the engineer, was seriously wounded by the same bullet. The robbers fled after the shooting, without securing any booty. Two of the highwaymen boarded the train at Troutdale, eighteen miles east of here, and crawled over the tender and to the engine, where they made the engineer stop near Corbett station. |

When the train stopped two more men appeared. Two of the robbers compelled the engineer to get out of the cab and accompany them to the express car, while the others watched the fireman. The men carried several sticks of dynamite, and, when they came to the baggage car, thinking it was the express car, threw a stick at the door. Kerner heard the explosion, and immediately got to work with his rifle. The first bullet pierced the heart of one of the robbers and went through his body, entering the left breast of Barrett, who was just behind. Barrett's wound is above the heart, and is not necessarily fatal. |

After the shooting the other robbers fled, without securing any booty, and it is supposed that they took to a boat, as the point where the hold-up occurred is on the Columbia River. |

The robbers ordered Barrett to walk in front while approaching the baggage car, but he jumped behind just before the express messenger fired. The body of the dead robber was left behind on the track, and the wounded engineer was brought to this city. Sheriff Story and four deputy sheriffs went on a special train to the scene of the robbery, where one of the gang of outlaws was found badly wounded from a charge of buckshot |

(Text box continued on next page)

which he received in the hand. He said that his name was James Connors of this city but refused to tell the names of any of the other bandits or the direction in which they went. The Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company offers a reward of $1 000 for the arrest of the highwaymen. |

SOURCE : New York Tribune September 25 1903p. 14. |

As David Levy has pointed out, it was within the genre of reenactment films that Porter exploited procedures that heighten the realism and believability of the image.[76]Execution of Czolgosz and Capture of the Biddle Brothers provided Porter with an approach to filming the robbery, chase, and shoot-out. In Execution of Czolgosz he had intensified the illusion of authenticity by integrating actuality and reenactment, scenery and drama. In The Great Train Robbery he took this a step further, using mattes to introduce exteriors into studio scenes. On location, Porter used his camera as if he were filming a news event over which he had no control. In scenes 2, 7, and 8 the camera is forced to follow action that threatens to move outside the frame. For scene 7 the camera has to move unevenly down and over to the left. Since camera mounts were designed either to pan or tilt, this move is somewhat shaky. This "dirty" image only adds to the film's realism. The notion of a scene being played on an outdoor stage was undermined. Biograph described the desired effect when advertising The Escaped Lunatic : "Fortunately there were a number of . . . cameras situated around the country . . . and this most astonishing episode was completely covered in moving pictures."[77]

The Chase

The chase became a popular form of screen narrative in 1903; The Great Train Robbery and Biograph's The Escaped Lunatic were the first American productions to reveal its impact. The chase appeared early in cinema history: an Irish cop chases a "Chinaman" through a revolving set in Chinese Laundry Scene (1894), and a mad dash lasting a split second ends G. A. Smith's The Miller and the Sweep (1898). James Williamson's Stop Thief! (1901 ) isolated the provocation, the chase, and the resolution in three different camera setups. These remained isolated occurrences. Porter's Jack and the Beanstalk (1902), for instance, ignored the dramatic potential of the chase as the giant climbs down the beanstalk after Jack. According to American catalogs and trade journals from the early nickelodeon era, the two English imports A Daring Daylight Burglary and Desperate Poaching Affray initiated the craze.[78] The chase provided a new kind of subject matter, a new narrative framework that would be elaborated and refined in succeeding years until one-reel pictures such as Griffith's The Girl and Her Trust (1912) and Mack Sennett's comedies had seemingly exhausted its possibilities within their alloted one thousand feet.

Although the chase is implied throughout most of The Great Train Robbery , it only becomes explicit for a single shot (scene 12). The Escaped Lunatic , in contrast, makes the chase the dominant element of the film, as it would be for subsequent Biograph subjects such as Personal (June 1904) and The Lost Child (October 1904). As used by Biograph, the chase encouraged a simplification of story line and a linear progression of narrative that made the need for a familiar story or a showman's narration unnecessary. These chase films locate the redundancy within the films themselves as pursuers and pursued engage repeatedly, with only slight variation, in the same activity. Rather than having a lecture explain images in a parallel fashion, rather than having the viewer's familiarity with a story provide the basis for an understanding, chase films created a self-sufficient narrative in which the viewer's appreciation was based chiefly on the experience of information presented within the film. This had, of course, been true for certain types of films since the 1890s, most particularly trick films and some actualities. The chase, however, greatly expanded the domain and the means by which this relationship between audience and screen subject could operate.

While The Escaped Lunatic and its English predecessors pointed the way to a more modern form of storytelling by presenting a self-sufficient narrative, they did not inaugurate a full-scale transformation of the representational system, which was necessary before this modern viewer/screen relationship became the dominant mode of reception. Although historians usually place The Great Train Robbery at the cutting edge of cinema, noting correctly that it was often the first film to play in an opening nickelodeon, Porter's work can already be seen as moving at a tangent to cinema's forward thrust. Porter's initial use of the chase was not to create a simple, easily understood narrative but to incorporate it within a popular and more complex story.

The Railway Subgenre: Spectator as Passenger

To be fully appreciated, The Great Train Robbery must be situated within the travel program's railway subgenre. The railroad and the screen have had a special relationship, symbolized by the Lumières' famous Train Entering a Station (1895) and half a dozen other films. Both affected our perception of space and time in somewhat analogous ways. Describing the shift from animal-powered transportation to the railroad, Wolfgang Schivelbusch has remarked: "As the natural irregularities of the terrain that were perceptible on the old roads are replaced by the sharp linearity of the railroad, the traveler feels that he has lost contact with the landscape, experiencing this most directly when going through a tunnel. Early descriptions of journeys on the railroad note that the railroad and the landscape through which it runs are in two separate worlds."[79] The traveler's world is mediated by the railroad, not only by the

compartment window with its frame but by telegraph wires, which intercede between the passenger and the landscape. The sensation of separation that the traveler feels on viewing the rapidly passing landscape has much in common with the theatrical experience of the spectator. It is not surprising, therefore, that an important subgenre of the travelogue centered on the train. This equation of train window with the screen's rectangle found its ultimate expression with Hale's Tours.

In the 1890s illustrated lectures, often known as "lantern journeys," featured railroads as the best way to reach and view American scenery. These frequently created a spatially coherent world with views of the train passing through the countryside, of the traveler/lecturer in the train, of scenery that could be seen out the window or from the front of the train, and finally of small incidents on sidings or at railway stations. The railroad, which carried its passengers through the countryside, was ideally suited for moving the narrative forward through time and space. John Stoddard and other lecturers presented these journeys as alternatives to travel for those who lacked the time, money, or fortitude for such undertakings.[80] Offering personal accounts of their adventures, these professional voyagers were figures with whom audiences could identify and from whom they could derive vicarious experience and pleasure. Audience identification with showman Burton Holmes took place on three levels—with the traveler shown by the camera to be within the narrative—a subject of the camera; with the showman as the cameraman—the producer of images of a certain quality; and, finally, as a speaker at the podium—with a certain voice and narrational perspective. The point-of-view shot out the window or from the front of a train was privileged in such a system because it conflated camera, character, and narration.

The introduction of moving pictures reinforced the parallels between train travel and projected image. "According to Newton," observes Schivelbusch, "'size, shape, quantity and motion' are the only qualities that can be objectively perceived in the physical world. Indeed, those become the only qualities that the railroad traveler is now able to observe in the landscape he travels through. Smells, sounds, not to mention the synesthetic perceptions that were part of travel in Goethe's time, simply disappear."[81] This new mode of perception, which is initially disorienting, then pleasurable, is recreated as the moving pictures, taken by a camera from a moving train, are projected onto the screen.

The epiphany of going through a tunnel likewise found a prominence in this subgenre that matched its significance in train travel. An early review of such a film begins by contrasting the resulting effect to an earlier moving picture novelty derived from pre-cinema lantern shows—the onrushing express:

The spectator was not an outsider watching from safety the rush of the cars. He was a passenger on a phantom train ride that whirled him through space at nearly a mile a minute. There was no smoke, no glimpse of shuddering frame or crushing wheels.

What Happened in the Tunnel. Outwitted and humiliated,

the "masher" tries to hide behind a newspaper.

There was nothing to indicate motion save that shining vista of tracks that was eaten up irresistibly, rapidly, and the disappearing panorama of banks and fences.

The train was invisible and yet the landscape swept by remorselessly, and far away the bright day became a spot of darkness. That was the mouth of the tunnel, and toward it the spectator was hurled as if a fate was behind him. The spot of blackness became a canopy of gloom. The darkness closed around and the spectator was being flung through that cavern with the demoniac energy behind him. The shadows, the rush of the invisible force and the uncertainty of the issues made one instinctively hold his breath as when on the edge of a crisis that might become a catastrophe.[82]

As this novelty wore off, phantom rides became incorporated into the travel narrative, enabling the showman to literalize the traveler's movement through time and space.

The railway subgenre soon incorporated short scenes for comic relief. G. A. Smith made a one-shot film of a couple kissing in a railway carriage—a gag that had comic strip antecedents. He suggested that showmen insert Kiss in the Tunnel into the middle of a phantom ride, after the train had entered the tunnel. Unlike the structuring strategies suggested by Selig,[83] comedy and scenery were contained within the same fictional world. Ferdinand Zecca's Flirt en chernin de fer (1901) was intended for the same use, but rather than require the entrance

A Romance of the Rail. Not only does Phoebe Snow wear a white gown on the Lackawanna

Railroad, but tramps ride the rails in their evening dress and decline a dusting off from the

astounded conductor.

of the train into a dark tunnel, Zecca matted in a window view of passing countryside. A Lubin film, Love in a Railroad Train (1902), depicts a male traveler's unsuccessful attempts to sneak a kiss from a woman passenger. When they emerge from the tunnel, it turns out that he is kissing her baby's bottom.[84] Porter combined a variation on Lubin's gag with Zecca's use of a matte to make What Happened in the Tunnel . A forward young lover (G. M. Anderson) tries to kiss the woman sitting in front of him when the train goes into the tunnel but ends up kissing her black-faced maid instead. The two women, who anticipate his attempt and switch places, have a laugh at his expense. The substitution of a black maid for a baby's bottom suggests the casual use of demeaning racial stereotypes in this period. What Happened in the Tunnel was the last film Porter made before The Great Train Robbery : its matte shot served as an experiment for similar efforts (scenes 1 and 3 of the headliner).

A Romance of the Rail , filmed in August but not copyrighted until October 3, 1903, elaborated on the comic interlude. To counter its image as a coal carrier, the Lackawanna Railroad, known as "The Road of Anthracite," developed an advertising campaign in which passenger Phoebe Snow, dressed in white, rode the rails and praised the line's cleanliness in such slogans as:

Says Phoebe Snow, about to go

Upon a trip to Buffalo:

"My gown stays white from morn till night

Upon the Road of Anthracite."[85]

A Romance of the Rail lightheartedly spoofs not only the slogans but the advertisements' photographic illustrations. Like Rube and Mandy at Coney Island , the film combines scenery and comic relief. The narrative is clearly paramount

as Phoebe Snow meets her male counterpart (also dressed in white) for the first time at a railway station. They fall in love and marry in the course of a brief ride, spoofing romantic associations with train travel. Scenery is pushed into the background, except in the fourth shot, where the camera framing gives equal emphasis to the scenery and the couple, who are, like the spectator, watching the scenery. Although Romance of the Rail has a beginning, middle, and end, it lacks strict closure since exhibitors often inserted the film into a program of railway panoramas. The ratio and relative importance of scenery to story were left to their discretion.

Audiences for these films continued to assume the vicarious role of passenger. One moment they would be looking at the scenery from the train; at another they would be looking at the antics of fellow passengers. Hale's Tours made this convention explicit by using a simulated railway carriage as a movie theater, with the audience sitting in the passenger seats and the screen replacing the view from the front or rear window. This theater/carriage came complete with train clatter and the appropriate swaying. The superrealism of the exhibition strategy was adumbrated by bits of action along the sidings and in the train, which contradicted the suggestion of a fixed point of view. Coherence was sacrificed in favor of variety and a good show. Whether What Happened in the Tunnel or A Romance of the Rail were used in the first Hale's Tour Car at Electric Park in Kansas City during the summer of 1905 is not known, but such use would seem logical.[86] When Hale's Tours became a popular craze in 1906, however, these films were advertised again in the trades as "Humorous Railway Scenes" with this purpose specifically in mind.[87]

The Great Train Robbery brought the railway subgenre to new heights. During the first eight scenes, the train is kept in almost constant view: seen through the window, as a fight unfolds on the tender, from the inside of the mail car, by the water tower, or along the tracks as the cab is disconnected and the passengers are relieved of their money. Although the film was initially shown as a headliner in vaudeville theaters with its integrity intact, it was also introduced by railway panoramas in Hale's Tours—type situations. The spectators start out as railway passengers watching the passing countryside, but they are abruptly assaulted by a close-up of the outlaw Barnes firing his six-shooter directly into their midst. (This shot was shown either at the beginning or end of the film. In a Hale's Tours situation it would seem more effective at the beginning, in a vaudeville situation at the end as an apotheosis.) The viewers, having assumed the role of passengers, are held up. The close-up of the outlaw Barnes reiterates the spectators' point of view, brings them into the subsequent narrative, and intensifies their identification with the bandits' victims. Since this shot is abstracted from the narrative and the "realistic" exteriors of earlier scenes, the title that the Edison catalog assigned to this shot—"Realism"—might at first appear singularly inappropriate.[88] Yet the heightening of realism in twentieth-century

cinema has been associated not only with a move toward greater naturalism but with a process of identification and emotional involvement with the drama. It is this second aspect of realism that the close-up intensifies.

The process of viewer identification with the passengers in a Hale's Tour presentation of The Great Train Robbery was overdetermined: introductory railway panoramas, reinforced by the simulated railway carriage and the close-up of Barnes, turned viewers into passengers. These strategies of viewer identification coincided with the viewer's social predisposition to side with responsible members of society being victimized by lawless elements. The second portion of the film, however, breaks with the railway subgenre and this overdetermination and becomes a chase. The presence of the passengers is forgotten. Music or simulated gunshots, rather than railway clatter, became the appropriate sound effects.[89] The breakdown of the viewer-as-passenger strategy, always just below the surface of the railway genre, was complete by the end of the film. This breakdown subsequently occurred on an entirely different level as well. Adolph Zukor, who would work with Porter ten years later, managed a Hale's Tours car in Herald Square during the early stages of his motion picture career. After the venture's initial success, he began to lose money until the customary phantom rides were followed by The Great Train Robbery . Although this combination revived his customers' interest and his own profits, Zukor eventually replaced the simulated carriage with a more conventional storefront theater.[90]

Another Change in Personnel

Early in 1904 the Edison Manufacturing Company was forced to find yet another manager for its Kinetograph Department. Shortly after the release of The Great Train Robbery , William Markgraf went to England on motion picture business. Once there, he went on a month-long drunken binge. In the midst of his alcoholic haze, he bought at least 200,000 feet of Lumière film stock without proper authorization.[91] Gilmore was forced to call his brother-in-law back to the United States and ask for his resignation. Although Markgraf's salary was terminated in late March, he had been effectively removed from any position of responsibility somewhat earlier. Perhaps because Porter assumed extra responsibilities as a result—and could claim credit for The Great Train Robbery —the studio manager's salary, which had been raised to $25 per week in October, was increased again to $35 per week. Moreover, an M. Porter, undoubtedly Porter's youngest brother Everett Melbourne, was hired at $4 per week—an office boy's salary—early in the year.

Few promising candidates appeared to fill the position Markgraf was vacating. Alex T. Moore, who had known Gilmore since their mutual employment by Edison electric light companies, applied for the job sometime in January.

Gilmore, uncertain of Moore's qualifications, sent him to be interviewed by Percival Waters at the Kinetograph Company. As Waters later recalled,

Moore came into my office one day with a card of introduction from Mr. Gilmore. He stated to me that he had applied to Mr. Gilmore who was an old friend of his for a position with the Edison Manufacturing Company. Mr Gilmore said to him that he might have an opening in the film manufacturing department, but thought that he would require a man experienced in the moving picture business and suggested that he call upon me and talk over the requirements of that business. I told Moore that I would be very glad to give him any information which I had and went over my experience and what I thought would be required of a manager of such a department. He said that he believed he could easily pick up the details. He thanked me for the information I had given him and I told him that if he should secure the position he must feel that he could call upon me at any and all times and that I would do my best to acquaint him with the business. Afterwards, said Gilmore asked me if I had seen Moore and I told him that I had and that he seemed to have a good appearance and I didn't question but that he could operate the department satisfactorily.[92]

Waters' ties with the Edison Company had developed sufficiently for him to exercise an indirect veto over the hiring of key personnel. The exhibitor may have even been pleased at the prospect of working with an inexperienced manager, since the novice would frequently be dependent on him and his knowledge of the industry. Moore's assumption of the position in late March inevitably strengthened Waters' ability to make Edison's Kinetograph Department serve the interests of his Kinetograph Company.

Moore was conditionally hired at $50 per week. After a two-month trial, his salary was raised to $75 per week, including retroactive pay. One of Moore's first orders of business was to dispose of Markgraf's legacy of Lumière film, which had proved defective. When the stock was run through a projector, the emulsion stripped off the base. It could only be used as leader. (No wonder Eastman Kodak dominated the industry!) Joseph McCoy, Edison's undercover agent, later reminisced about the disposal of the unsatisfactory material:

Moore wanted to get clear of the Lumiere Company film. I was to sell the film to other manufacturers of films and the Edison Company was not to be known in the transaction.

I sold some of the film to the Edison Company at 4¢ a foot. Other manufacturers said if it was good enough for the Edison Company to use, they would buy some of the film.

I sold 160,000 feet of the Lumiere film. Geo Melier [sic ] of East 38th Street [sic ] bought 10,000 feet. Smith of the Vitagraph Company bought the film and Lubin of Philadelphia. They all had the same trouble with the film stripping from the celluloid base.[93]

McCoy's practical solution typified the business ethics often practiced by Edison, his associates, and American industry. Today it would be called fraud.

Although The Great Train Robbery caused Edison film sales to surge in December 1903, such "headliners" were still considered only one dimension of Porter's production responsibilities. The producer thus turned his attention to making short comedies, including the timely Christmas subject Under the Mistletoe , and filming winter scenery, for example Crossing Ice Bridge at Niagara Falls and Ice Skating in Central Park, N.Y . Multishot comedies like Casey's Frightful Dream (January 1904) and Little German Band (February 1904) were increasingly typical. The latter film required three different studio sets—one for each shot. A small band plays music outside a saloon, and the owner invites them inside, generously giving each a glass of beer. They drink up and after one musician surreptitiously fills his tuba with brew from a conveniently located keg, they depart. Outside the band share the spoils, using their instruments as drinking vessels. The suspicious saloon keeper, however, catches them in the act. If children can be naughty and escape retribution in most early films, men who act like boys are rarely so lucky. In these comedies, punishment of adults usually involves social or sexual humiliation.