Arthur Laurents: Emotional Reality

Interview by Pat McGilligan

Of all the screenwriters in this book, Arthur Laurents lived in Hollywood the least amount of time—just over two years, in the late 1940s, when the blacklist dovetailed with his own inclination to travel in Europe and, eventually, to concentrate his energies in theater on the East Coast.

A member of the National Theatre Hall of Fame, he has been primarily active, and is perhaps better identified, as a Broadway playwright, among whose many successful plays are included the "books" for the landmark musicals West Side Story and Gypsy . Also a noted theater director, Laurents won a Tony for his staging of the musical La Cage aux folles and recently directed the Broadway revival of his own Gypsy (for which Tyne Daly earned a Best Actress Tony).

In spite of the fact that his résumé includes only a handful of motion pictures scattered over three decades, and that he regards his work in that field with (at best) mixed emotions, Laurents is to be found in most reference books and is acknowledged by most students and scholars of the cinema as a screenwriter of distinction.

There has been a lot of hooey and mystification about his film credits, which he is pleased to dispel. Laurents does not glow with happy things to say about Hollywood, then or now, no matter that motion pictures provided opportunity, growth, and recognition in his career.

• Some source books indicate that the script for The Snake Pit (1948) is not his, particularly. Laurents says, yes, it is, very much so; it is just that the credit was stolen.

• Critics rhapsodize about Max Ophuls' melodramatic film noir Caught (1949). Laurents tells a hilarious anecdote about the low-budget economiz-

ing necessary in the script and shooting, and debunks director Ophuls, an auteurist favorite elsewhere elevated to Andrew Sarris' pantheon of directors.

• The screen rendition of Laurents' play The Time of the Cuckoo, which is David Lean's Summertime (1955), was mangled by none other than Katharine Hepburn, according to Laurents.

• Rare among U.S. screenwriters, Laurents tried to broach homosexuality as a subtext in Alfred Hitchcock's Rope in 1948 (the casting agents and the stars of choice—Cary Grant and Montgomery Clift—wouldn't go for it) and as a context for the ballet-world drama The Turning Point in 1977 (it was snipped out of the picture).

• Laurents also airs caveats about Otto Preminger's screen adaptation of Françoise Sagan's Bonjour Tristesse (1958), the film versions of Gypsy (1962) and West Side Story (1961), his box-office triumph The Way We Were (1973) . . . and so on.

A man of integrity and virulence, Laurents does not give many interviews on the subject of screenwriting, but he agreed to see me after reading some of what I have written, sympathetic to his point of view, on the subject of the Hollywood blacklist.

Laurents is adamant on the injustice of that period, which saw careers abridged and lives destroyed by the anti-Red hysteria. Laurents says the blacklist took all the best and brightest people out of Hollywood, ushering in the blandness, compromise, and conventionality of much of 1950s film culture. Laurents himself left on the cusp of the worst fallout—it is unclear to what extent he was blacklisted, as he chose not to wait around for the bad tidings—and never returned to the West Coast for any extended period.

The blacklist is the backdrop for the popular motion picture starring Robert Redford and Barbra Streisand, The Way We Were . The love story between a quintessential Golden Boy and kooky Jewish radical begins on a city college campus, against a panorama of 1930s causes, and climaxes at the height of the Hollywood inquisition. Laurents wrote the screenplay for the adaptation of his own excellent novel (though he was fired at one point, he returned to complete the script during filming).

But the thematic crisis of the novel, which revolves around the Golden Boy's decision to surrender to career pressures and cooperate with the anti-Red forces, was too complex and bitter a plot pill for the producers of the movie. The crucial scene, the moral confrontation between the Redford and Streisand characters, was left on the cutting-room floor, much to Laurents' anger and regret.

Even so, The Way We Were is the kind of romantic movie Laurents is most identified with—not only a funny, sentimental, broadly appealing love story,

but one that is ultimately star-crossed, tragic, bittersweet. The trajectory of a character melodrama set against the exigencies of a particular social milieu has been the territory of much of his writing: the attraction of peculiar opposites, poignant ideals in conflict with hard reality, the collision of emotions against the boundaries of class. These ideas mirror, to a certain extent, his own upward striving, but one of the things that people admire most about Laurents is his ability to weave a script that is, above all, a grand entertainment.

After some coordination with his busy schedule, I met with the seventy-year-old playwright-screenwriter at his Greenwich Village address. He proved to be articulate, opinionated, provocative, and bitchy, as is his reputation (People magazine once dubbed him "a put-down artist"). He picked an argument with me about the current Broadway musical sensation Les Misérables, which he detested and I rather liked; and throughout the interview he weaved around and dodged my more personal questions, insisting that I was trying to categorize him. (I was not.) Much that was interesting was uttered off the record.

Even at that, when I showed Laurents a transcript of the interview, he wondered if they were really his words. Then, taking some imagined offense, he said he would not pose for a portrait photograph.

Arthur Laurents (1917–)

1948

The Snake Pit (Anatole Litvak). Uncredited contribution.

Rope (Alfred Hitchcock). Script.

1949

Home of the Brave (Mark Robson). Based on his play.

Caught (Max Ophuls). Script.

Anna Lucasta (Irving Rapper). Co-script.

1955

Summertime (David Lean). Based on his play The Time of the Cuckoo, uncredited contribution to film script.

1956

Anastasia (Anatole Litvak). Script.

1957

The Seventh Sin (Ronald Neame). Uncredited contribution.

1958

Bonjour Tristesse (Otto Preminger). Script.

1961

West Side Story (Robert Wise). Based on his musical play.

1962

Gypsy (Mervyn LeRoy). Based on his musical play.

1973

The Way We Were (Sydney Pollack). Co-script, adapted from his novel.

1977

The Turning Point (Herbert Ross). Script, co-producer.[*]

* Film Facts (1980), the revised edition of Reel Facts (1978 ), lists Avery Corman as co-writer with Laurents of The Turning Point, winner of 1977's "Best Written Drama—Written Directly for the Screen" from the Writers Guild .

A publicity photo (circa the 1960s) of playwright-screenwriter Arthur Laurents.

(Photo: Photofest)

Novels include The Way We Were .

Plays include Home of the Brave; Heartsong; The Bird Cage; The Time of the Cuckoo; A Clearing in the Woods; West Side Story; Gypsy; Invitation to a March; Anyone Can Whistle; Do I Hear a Waltz?; Hallelujah, Baby; The Enclave; Scream; The Madwoman of Central Park West .

Academy Award nomination for Best Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen for The Turning Point in 1977.

Writers Guild awards include best-script nominations for Home of the Brave, Gypsy, and West Side Story. The Snake Pit won the Best-Written American Drama award in 1948, though Laurents' contribution went uncredited. The Turning Point earned Best-Written Drama Written Directly for the Screen in 1977. That prize was shared by Laurents with writer Avery Corman, although Corman was not credited in publicity or on the screen.

Tell me why you became a writer .

I'd always wanted to be one since I was ten years old.

But why?

I don't know.

Were your parents writers?

No.

Were you an avid reader?

Of course. I don't think anybody knows why he became anything. I think there is a terrible desire to overexplain such things.

Some people have mentors, teachers or parents who nudged them along. Some people read and admired writers greatly. Some people grew up in the shadow of Broadway and devoted themselves to a Broadway career for that reason .

Well, those are people who are ambitious. That doesn't say anything about wanting to do whatever comes out of you. Some people write, some people paint, some people do neither. I see you go in for categorized thinking.

No. Not at all. I don't come here with any presuppositions. I might say I wanted to be a writer when I was ten years old, too, but I wanted to be a lot of other things, too .

Well, I wanted to be a writer, period.

Did you write when you were ten years old?

Yes.

When did you begin to write professionally?

Oh, I guess when I was around twenty.

That's when you were in the service?

Actually before. I had some friends who were all performers. They wanted to do one of those bright-young-thing revues, and they asked me to write some stuff for them. That was the first. Cabaret. Nightclubs. There was no off-Broadway then.

Then actually I began writing radio before the service.

Why radio?

Because I could sell to radio. I have always believed in supporting myself by my writing, and I have been very fortunate in that I always have.

What kind of radio? Serious radio drama?

Yes. After I graduated from Cornell, this girl I knew told me about a course in radio writing, so I went. The teacher was one of the directors of the Columbia Workshop. He asked us to do an adaptation, which I didn't do, because I wasn't interested [in adaptation]. But when he asked us to do something original, I wrote something, and the Columbia Workshop bought it. The going price for a script then was $100. They gave me $30 because that was [the cost of] my tuition. That was my first encounter with capitalism.

And your first professional sale?

Yes. Then, I did a lot of radio scripts when I was in the army. As a matter of fact, the army acted as my agent. There was a program called "The Man Behind the Gun." That was a commercial CBS program about the army. The army negotiated a deal for me, because [from their point of view] I was writing army propaganda. I made what seemed a great deal of money. Three hundred dollars a script.

Did you write your first play, Home of the Brave, after World War II?

I wrote Home of the Brave while I was in the army. And that, for me, was the end of radio.

Was Home of the Brave based on a real occurrence?

It was based on a photograph in a newspaper of some soldiers in the jungle. When I was writing this government propaganda program, I used to make up stories. I looked at this photograph, I made up some story, and that led to Home of the Brave .

Actually, how I came to write Home of the Brave is rather interesting. If, at a certain time of your life, someone says something to you, and you're ready to hear it, it'll have an effect. I used to drink and carouse quite a bit in the army. One time I went to a cocktail party and there was an actor there named Martin Gabel. He said to me, "You keep writing these things and you'll never write a play. And you're good enough [to write a play]." So I went home and I wrote that play in nine days while I was also writing army stuff. It took a long time to get it produced. Too long. I was in the army for almost five years. The war was over by the time it was produced.

Partly because of the nature of the subject?

Uh-huh.

I have seen the film version [Home of the Brave, 1949], and I thought it was surprisingly good. It stands up well, considering what I had read about it in reference books, before I caught up with it, one late night on television .

Well, the play was about a Jew.

The movie is about a black man .

Yes, because the film people said Jews had been done.

Really, who said that?

Stanley Kramer. Which is a real Hollywood story. But it's not just a joke. That's what Hollywood is like. Kazan had made a picture called Pinky [1949],

about a mulatto, played by Jeanne Crain with heavy makeup. They also made a big success of a movie called Gentleman's Agreement [1947]. I thought the point of that novel and movie was, you had better be nice to a Jew because he is probably a Gentile. It was silly. I knew it then.

My objection to the movie of Home of the Brave is that [after they changed it to being about a black man] they stayed too close to the play, and therefore the movie was untrue. You would never have found, in those days, what was called a Negro, in a white unit.

So, in other words, when they transposed it, it became unreal?

Well, yes. At the same time, the film was successful. After all, movies are a mass medium, a lot of people saw it, and I hope it helped about prejudice.

And even though Stanley Kramer's remark is ludicrous, making the theme about black-white racism was equally brave .

Oh, it was. I don't mean to castigate him, because in all of his movies he [Kramer] has really tried to combine something that he feels is important to say with something that is commercial. I see no virtue in finding something important to say in a failure. If you say it is "too artistic for the people," I think you're kidding yourself.

When I have written movies, I have been very aware that you have to adjust your head. When somebody says to me, "We're going to make a picture for X million dollars," that means it has to reach X million people. That day you have to come down from your very fancy mountain and say, "Okay, how can I do what I want to do without compromising myself, and yet reach those people?" It's hard, but you can do it.

Were you thinking that, specifically, when you just started out? When you wrote something like Home of the Brave?

Oh, that was for the theater. You don't think that way in the theater. That's one of the beauties of the theater.

Because in the theater, they can take it or leave it. They'll come if it's good . . . ?

I don't know if they'll come or if they won't. I don't think about that. When I write a play, all I think of is: I want it to be as good as I can make it. You are more calculating in screenwriting; at least I am. In a movie you're a hired hand and if you think you're anything but, you're kidding yourself. I worked in movies, beginning in 1947, for the first time, and in 1978, for the last time, I think. The situation has not changed. The writer is low man on the totem pole unless he is the director. Not the producer. I was co-producer of The Turning Point . Didn't mean a damn.

You learned how to write for radio in a workshop, and then you learned by doing. How did you learn to write a Broadway play?

By writing. I went to the theater as a child. I'm from New York, my Dad was a lawyer, and his secretary used to take me to the theater. Then I went as a kid—alone. I would go to the theater alone when I was thirteen and four-

teen. I could hear them say, "Oh, look at that kid sitting there!" I just loved the theater.

I also read a lot, and mainly I learned from seeing [plays] and reading.

I also studied playwriting at Cornell. But the man who conducted the course was terribly didactic, an anti-Semite, and very contemptuous of me because I came from New York and was Jewish. The only thing I learned from him was "Never begin a play with the telephone ringing." So later I wrote a one-act play that began with a telephone ringing. Boy, I learned nothing from him!

One of the things I said to myself [when I was young] was, if I ever write a play, it's not going to have a cast of one gender, and it's certainly not going to have outdoor scenes, because they look awful [on the stage]. Then I wrote Home of the Brave . It's [a cast of] all men, and most of it takes place in the jungle, which shows you that no matter what you say or think, ultimately it's what comes out of you. And you have to go with that.

What brought you to Hollywood? Home of the Brave?

No. What brought me to Hollywood was needing money. [Director] Anatole Litvak, who became a great friend, wanted me to do The Snake Pit, after Home of the Brave, because they were both "psychiatric." I didn't want to go to Hollywood. I wanted to stay in the theater, so I wrote another play. It failed, and by that time I was in debt. So I had to go to Hollywood. I ended up going to California for Metro.

Is that where The Snake Pit was being filmed?

No, no. Litvak was at Fox and he had two writers working on The Snake Pit —Millen Brand and Frank Partos.[*]

So I was at Metro. The interesting thing about the studios is their attitude towards writers. They treated you as though they knew they needed a writer. And they knew that, unlike [the case of] an actor, you could not get a writer to do something he did not want to do, because it would just be a disaster. So they would assign me things to write, I would say I didn't want to do them, and they wouldn't fire me. I had a sixteen-week contract with renewals, and I kept turning down everything.

When Tola [Anatole Litvak] asked for me on The Snake Pit, MGM wouldn't let me out of my contract. I asked to be released, and finally MGM loaned me to Fox to do The Snake Pit, because Fox paid MGM more than I was getting [in salary]. Tola was on deadline with that script, because they were

* The Snake Pit is Millen Brand's only screen credit in the official Writers Guild catalogue of credits, Who Wrote the Movie (and What Else Did He Write)? (1936–1969) . Frank Partos (né Partes), a short-story writer from Budapest, had been in Hollywood since the early 1930s and had numerous screen credits, including Jennie Gerhardt (1933), The Last Outpost (1935), Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), The Uninvited (1940), and And Now Tomorrow (1944). His film credits stop after 1956.

ready to go into shooting and the script was no good. I sat all day and all night with Tola, rewriting at the Fox studio. Finally the script was done and they began shooting it.

A friend of mine, Irene Selznick, said, "You ought to do something; your name's not on that script." Well, credits never meant anything to me. But I said something about it to Tola, who, as I say, remained a great friend despite this incident which I'm going to tell you about. He said, "Well, that's ridiculous. You wrote the script! We had to throw out what they wrote." When the picture was finished, the credit went to the Screen Writers Guild [for arbitration], and they ruled that Millen Brand and Frank Partos had written it. There was no screen credit for me. The guild hearing was during the shooting of the picture, and Tola said he was too busy to attend to testify. So I didn't get screen credit!

I remember being at the closing party. . . . The other screenwriters weren't there, and Olivia De Havilland and all the others were all very nice to me. I was a little annoyed, but not really, because I thought, and I still think, what difference? I mean, I know I wrote it, most of it. Credits never meant anything to me.

Then the irony. Hollywood is an irony unto itself. I stayed on [in Hollywood], and I rented a little house which belonged to Millen Brand, who, interestingly enough, was a Communist. I say that because in my experience the Communists out there were extremely decent people, as left-wing people always are, in my opinion. Not all, but most. And Millen Brand apologized to me. It was wrenching for him to do this because he was a very moral man. But he had a wife whom he was insane about, and she was telling him it [the screen credit] would help him get other jobs. He didn't want to write movies anyway. So he lied. And the wife left him anyway.

It would have been a shared credit in any case, right?

Well no, because they do it on percentage.

And your percentage would have —

Knocked them out. They did something really clever, but dastardly. There was a whole slew of scenes that were nothing like anything they'd written, so they typed them up and threw away the originals and kept the carbons as though they had written them. I didn't learn about that [trick] until after on.

Later on I wrote another picture [The Seventh Sin, 1957], a modernization of a picture called The Painted Veil [1934], a picture Garbo had made. It was supposed to be for Ava Gardner, or somebody like that; an extremely glamorous person; then they changed the casting to Eleanor Parker, so I knew the picture wouldn't work. They wanted changes [in the script]. I said I was not going to make any changes, for that reason. They got somebody else in to make the changes who then went over the whole script and when it said, "I don't do this," he changed it to, "I do not do this," because, you see, that gave him the percentage.

When you live in a town with that going on, if you let it get to you, you're an ass. If you stay there, you're a hack.

How did you learn screenwriting—again, by doing?

By doing.

Did you know any screenwriters?

No. You visualize. I happen to be very visual. And if you have some talent, you know there's a rhythm to all writing, even the rhythm of a sentence. Rhythm if particularly important in film. So you write with a rhythm. That you can't teach. You either feel it or you don't.

I have never imposed any discipline when I am writing. When I'm ready to write, I write.

I walk around with an idea. I don't know where it comes from. It usually begins with an image. In working it out, for whatever medium, you relearn the same things, or at least I do, every time. You make the same mistakes. The cardinal thing is always trying to remember that a script begins with character. Not with what you want to say. It begins and ends with character.

Did any screenwriters take you in hand simply to learn the screenplay form? Or did anybody?

The second picture I did [Rope ] was with Hitchcock, and that was a weird one because it was originally a play. Hitchcock wanted to do it as a play, which is why he got me. That picture was made with nine [ten-minute] takes.[*] He photographed it as a play, on one set. I loved working with him. The really first-rate directors I worked with, Litvak and Hitchcock, I got on marvelously with. The ones I had iffy relationships with were second- and third-rate.

Why did you get on marvelously with Hitchcock? Was it because he had useful script ideas?

You have to remember I was in my twenties. But Hitchcock treated me with respect. And soon I was learning from him. For one thing, he never had to use the viewfinder. He knew what was in every frame. It was always worked out beforehand.

We didn't agree entirely on everything. There were two big battles. I won one and lost the other. You know, the play is about a boy being strangled. Well, [in the film] he wanted a bottle of red wine to tip over on the chest as some kind of frisson . I said, "But if you strangle someone, there wouldn't be any blood, so it's pointless [as symbolism] and it would be obvious." And he finally agreed.

The other [battle was about the picture beginning] with seeing the murder in silhouette. I was against that. I said you should never know until the end whether there was anything in that chest or not. He tacked that [beginning] on after the film was made.

I was very close to Hitch. He was a child, you know, a very black-comedy

* In actuality Rope is composed of ten unbroken takes of approximately ten minutes each.

child. A really macabre humor. Very weird, sexually. I would go to these parties at his house and there were always the same people: Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman and Grace Kelly and Hitchcock's entourage. It sounds like I'm dropping a lot of fancy names, but [at the time] you'd think, "Oh God, I have to go again to Daddy's. . . ." Except I didn't feel that way, really. They were sweet people.

Later, Hitchcock got mad at me. Because he worked with the same people as much as possible, and when he liked you, you were in his family. He wanted me to do the next picture, which was something called Under Capricorn [1949], I think, with Ingrid Bergman. I didn't want to do it, and he got very angry with me. Then we became friends, even after that. I turned down several things he wanted me to do, including Torn Curtain [1966] and Topaz [1969].

Why were you turning down films with Hitchcock if you liked him so much? Because they weren't good.

And you thought Rope was good when you started working on it, or were you in a different position, professionally?

No. I thought Rope was good. I thought Rope could have been marvelous if he [Hitchcock] had been able to cast it the way he wanted to, with Cary Grant and Monty Clift. But since Cary Grant was at best bisexual and Monty was gay, they were scared to death [of the casting] and they wouldn't do it. So Hitchcock got Jimmy Stewart as one of the leads, and he was dead wrong for the part.

The credits also say Hume Cronyn did some writing. I can't understand why it took so many people to adapt a play for the screen that was essentially filmed as a play .

I threatened to sue Cronyn because he was going around saying he wrote the screenplay. Cronyn was in Hitch's family. I don't know what that credit was about except that Cronyn was a friend of Hitch's and Hitch was like a boy when he liked you. If you ask me what the adaptation credit was for—I never saw the adaptation. But what did I care? Again, so what?

I have read that Ben Hecht also worked on Rope. Is that true?

No. I don't even think he was around.

In a short period of time in Hollywood, you went from being unemployed and having had just one successful Broadway play to being a writer of some stature, working for Hitchcock .

You have to remember I got awards for that play [Home of the Brave ]. Second of all, to this day no matter what they say, if you have anything done in the theater, and it runs three nights, they're impressed [in Hollywood]. Also, I was very young. So that made them more impressed. The only one who wasn't impressed was me.

Did you perceive differences in the way some studios treated writers? Was there a studio which was more of a haven?

Well, you could hardly call it a studio. Yes, there was a place called En-

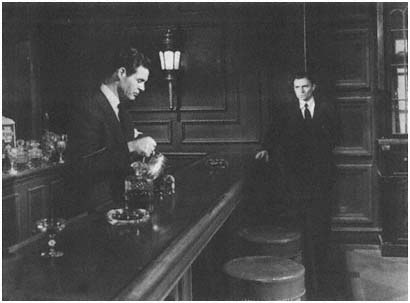

"I don't think he [Max Ophuls] was such a genius": Robert Ryan (foreground) and

James Mason in director Ophuls' Caught, script by Arthur Laurents.

(Photo: Museum of Modern Art)

terprise, where I did a picture with a director named Max Ophuls, who was supposed to be this great European genius, according to all these Film Comment and Sight and Sound articles. He was a very amusing man, wonderful with the camera. I don't think he was such a genius. I think his pictures are vastly overrated. The picture I did with him was called Caught .

I love it. I think it is wonderful .

Well, there's a piece by Pauline Kael, I think, which typifies my feeling about film critics. She talks about a certain sequence where it's all murky because of the psychological murkiness of the character and all this stuff. It is a scene where there is a Howard Hughes character who comes to a pier where this girl is waiting. The truth of it was there was no money [in the budget] even to get a picture of a motorboat off Malibu!

In Paris, I had seen a stage version of Anna Karenina . It was staggering, because you saw her at the train station, and when the train came in, you saw her throw herself in front of the train—on stage. I wondered how the hell they did that, and I went backstage to find out. Well, they had a lot of smoke, dry ice, and there was a wooden bridge and a stagehand with a huge spotlight on his hat; he came round the bend and the light shone straight at the audience; with the noise of the train and all the smoke, you thought you saw a train and

you thought you saw her jump in front of it. So I told that to Ophuls. In Caught, if you look at it [closely], what the motorboat is, is a sound, and the stagehand with the light on his head is bobbing up and down in front of a black velvet curtain. That's Pauline Kael's psychological murkiness. (Laughs .)

There's a wonderful Hollywood story about that picture, do you want to hear it?

Sure .

Ophuls had decided to do a picture for Enterprise and he wanted me to write it, why I don't know. They had bought a book called Wild —something—December [Wild Calendar ], maybe. Written by a woman named Libbie Block. The reason they bought it is that they wanted Ginger Rogers under contract. She wanted that book. After they bought the book, she decided she didn't want to work for Enterprise, so they were stuck with the book. Then they had a big screenwriter named Abe Polonsky write the script. He wrote a script. I never read the book, but I read his script, which was something about two brothers—one was dying, and he wanted the other one to marry his widow—which, I think, he did. Very strange. Almost an incestuous love between the two brothers. That was the picture Ophuls was going to make.

I read that script, out of courtesy, because my agent [Irving] "Swifty" Lazar told me, "Read it, kid, you've got nothing to lose." When I met with Ophuls, he said, "I don't want to do that story; I want to do the Howard Hughes story." I asked why. He said, "Because I hate Hughes." Ophuls had worked at RKO [under Hughes, who had acquired controlling interest of the studio in 1948]. Mind you, the picture now had millions spent on it, or whatever it was in those days—costs for things that were totally never used.

We started over from scratch. Then we went after the people we wanted for the picture, Robert Ryan and Barbara Bel Geddes, who were under contract to Howard Hughes. So we had to show Hughes the script about himself. (Laughs .) Eventually, for the hero they had to get James Mason, for his first American picture, with an English accent, playing an American! It was wild.

When they were ready to start the picture, Ophuls came down with shingles. So they hired a director, a left-wing guy named Jack Berry, not a very good director. At least he never did anything very good that I know of.[*] Anyway, Berry hated women. (A lot of those men out there [in Hollywood] talk about fucking women in the American pejorative sense.) The girl in the picture was based on a girl I knew who had been married to Sam Spiegel. One of those Texas beauties who was very sweet and very dumb. The fact that she was after money didn't make her a golddigger; that was the way she'd

* Laurents may have lost track of director Berry's career, for Jack Berry was also a blacklist victim. A former actor and director with Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre, Berry directed, among many other credits, a taut Hemingway adaptation before he was blacklisted, He Ran All the Way (1951), and afterwards, Claudine (1974).

been brought up; that was what you did, if you were successful, you married a guy who had some money. Well, Jack Berry turned the character into a whore, and he was also hot for Barbara Bel Geddes. They shot for twelve days, after which Ophuls got better, saw all the footage, and said, "Out! Out! Every bit of it."

Ophuls said to me, "We have to rewrite." We had only enough money left for four days of shooting, so I had to condense twelve days into four. It went on like that. That's Hollywood!

Did Ophuls have much script sense? Much script perception?

Not much. He was very easy. At Enterprise, the picture was produced by Gottfried Reinhardt's brother, Wolfgang, and he came from a whole literary tradition. He was the only one who talked script. He was charming and literate and weak. I mean, he was helpful—not about script, but about getting the money and getting the people—until it came to running interference with the studio.

Were you taking these early assignments principally for the money?

Partly. Also, for the time being, I had fallen in love with somebody. But I was also living in California, playing tennis, where it was all so beautiful. Then the [House Un-American Activities Committee] witch-hunt came. Though there was an extraordinary thing about the witch-hunt which I want to write about one day. It can sound very frivolous to say this, but it was exciting.

What was exciting was the lines were so clear. You saw who was good and who was evil, and I mean evil . In my book anyone who informed was evil. There was no excuse. They were evil, not just politically, because they were people who would have done something like that anyway. They were the kind of people who would always sell you out. In life . [Choreographer] Jerry Robbins, whom I did West Side Story with, did it to me on West Side Story .[*] These people had a streak in them. I don't care if it came from insecurity. I don't care if their parents were shits. After you turn twenty-one, you shouldn't be allowed to say that anymore. You are responsible.

I can remember sitting next to Eddie Dmytryk at several meetings to raise money for the families [of the Hollywood Ten] because these guys were going to the slammer. And what does Dmytryk do? He goes to the slammer, he comes out, and he testifies—because he needed a job. Understandable, but not condonable.

I thought Dalton Trumbo was disgraceful when he said, shortly before he died, that it didn't make any difference who were the victims [of the blacklist]. [**] That's absolutely balls. He worked all the time and he was fancy-

* Jerome Robbins' curiously "compliant" demeanor before the HUAC is discussed in Victor Navasky's Naming Names (New York: Viking Press, 1980).

** "It will do no good to search for villains or heroes because there were none," screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, one of the Hollywood Ten, told the Writers Guild-West upon accepting theLaurel Award in 1970. "There were only victims." His speech provoked controversy among the survivors of the Ten and among the Hollywood Left in general. See Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund, The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930–1960 (Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor/Doubleday, 1980), pp. 418–421.

schmancy with his cigarette holder. I thought that was a disgusting thing to say. You shouldn't take that kind of lofty attitude. When it comes down to people having jobs, I don't want any of this ersatz sophistication. He wasn't being forgiving; it was a misplaced cynicism.

It [the blacklist] has never left me. It will never leave me. I was blacklisted, so I left [Hollywood]. I was going to leave anyway.

Was there a point at which you became disillusioned with California itself, the culture and the motion picture industry, having little to do with the blacklist?

No, it was the witch-hunt. There were people in Los Angeles, at that time, who were marvelous. I was very friendly with Charlie Chaplin and met people at his house. There was a woman named Salka Viertel. She had an authentic salon [at her house] where I met Thomas Mann and [Bertolt] Brecht—for a kid, which I was, this was thrilling. You couldn't have met them in New York.

This existed until the witch-hunt cleaned these people out, and then Hollywood became what it is today, cardboard people running around on Styrofoam. The thing about it is, it always was a town where everybody is Cinderella and is terrified that 12 o'clock is going to strike, and eventually it does. But while you had these people around, my God, you just wanted to sit and listen!

The other part, all the jazz, was dazzling. There was this glamor. Irene Selznick was my mentor [in that regard]. She had produced my second play [Heartsong ], the flop one, and I had gone to Hollywood to pay her off. She gave me a list of parties (this is true): A-plus, A, A-minus, B-plus, B, B-minus . . . After that, I wasn't allowed to go. She got me invited. Well, after I was there six months, they were having a triple-tent anniversary party one night for John Huston, a director named Jean Negulesco, and I forget the third one.[*] Irene said, "What time are you getting there?" I said, "I'm not going." She said, "Didn't you get your invitation?" I said, "Yeah." She said, "Why aren't you going?" I said, "I've had it." She said, "How can you not go?" I said, "How can you go?" She said, "Well, I think tonight, it might happen . . ."

They're all children. If it's going to happen, it's going to happen in the supermarket . . . you don't have to go to fucking draggy parties.

Again, like the Martin Gabel story, there was a writer named Harry Kurnitz who once gave a party [in Hollywood] that I went to. I encountered him

* In Things I Did and Things I Think I Did by Jean Negulesco (New York: Linden Press/Simon & Schuster, 1984), pp. 199–200, the triple-tent party is colorfully recollected. The third director was Lewis Milestone.

there and he said, "What are you doing here?" I said, "You invited me." He said, "I mean, in Hollywood. Why are you still here?" I said, "Why are you?" He said, "You're a writer, I'm a hack. Get out." So I got out.[*]

At what point did the witch-hunt turn unexciting and threatening?

When everybody left. Then the town became unexciting. I remember an enormous farewell party for [producer-writer] Adrian Scott [one of the Hollywood Ten], who was leaving for France. Right after that [his wife, actress] Ann Shirley, backed out and left him at the last minute. That to me seemed to signal the end.

Was the left-wing politics at all helpful to the cultural atmosphere of Hollywood? Was it beneficial for writers? Was there any community of give and take?

Ah, no. I was in a Marxist study group [in Hollywood] and I learned a lot, but I learned a lot about politics, sociology, and economics, not about writing.

I thought people like John Howard Lawson were famous for coming up and making suggestions to other screenwriters .[**]

Well, I never met him. He was a left-wing majordomo, not a cultural majordomo. The people who influenced me were classier than John Howard Lawson. I mean, Salka [Viertel] was left-wing, yes, but [at her salon] you didn't hear people screaming, "Rise, ye prisoners of starvation." It was much more interesting than that. Charlie Chaplin was accused of being a left-winger, but he wasn't. He was totally individualistic, as a matter of fact—nonsensical, I thought, politically. But a marvelous man.

I read Lawson's book Theory and Technique of Playwriting and Screenwriting, which had an influence on me until I realized that, again, it was what I was baiting you about. It was too codified, too rigid, too compartmentalized and departmentalized. That's not the way you do good work. You have to do what you feel with the governor of craft and experience.

* Harry Kurnitz's many Hollywood script credits include Thin Man installments, What Next, Corporal Hargrove? (1945), The Web (1947), One Touch of Venus (1948), The Inspector General (1949), Land of the Pharaohs (1955), Witness for the Prosecution (1957), Hatari! (1962), A Shot in the Dark (1964), and How to Steal a Million (1966).

** One of Hollywood's more controversial figures of the 1930s and 1940s, John Howard Lawson was already well known as a politically committed playwright on Broadway before becoming a contract writer in Hollywood in 1928. A co-founder of the Screen Writers Guild, he was also its first president and one of the key organizers of its long struggle for recognition. At the same time, he was a behind-the-scenes eminence of the Hollywood branch of the U.S. Communist Party. His best films as a screenwriter include Blockade (1938), about the Spanish Civil War, and Action in the North Atlantic (1943). One of the Hollywood Ten, to some extent spokesman for the group, Lawson set the fractious tone for the public HUAC hearings into Hollywood politics when he vociferously refused to cooperate with the questioners. Blacklisted and eventually jailed, he was forced to quit screenwriting. He became a lecturer and the author of several noteworthy books on the theories and techniques of playwriting: Theory and Technique of Playwriting and Screenwriting (New York: Putnam, 1949); Film in the Battle of Ideas (New York: Masses & Mainstream, 1953); and Film: The Creative Process (New York: Hill & Wang, 1964).

I was not a member of the [Communist] party. But frankly, I believed in the goals [of the party], although I thought, even then, that the party members were extremely naive. But if somebody says to me, "Why were you never in the Communist party?" I would say, "Because they didn't ask me." Which is true. The reason they didn't ask me is because I would say things like "They don't have democracy in Russia. . . ." They'd say, "Well, you do vote . . ." I'd say, "But you have no choice, so it's not a vote. . . ." Well, that was heresy.

They were just children that way. Part of it was justified; part of it was just rebelliousness. Part of it was Jews and blacks, who felt understandably persecuted in this country and who were looking for an alternative.

I went to a fund-raising meeting once and had a big argument about the Hollywood Ten when they were standing on the First Amendment. I said, "I don't see anything in that First Amendment that allows you to do what you say. Stand on the Fifth. That's practical. Freedom of speech doesn't mean they can't fire you. . . ."

I think a lot of them [Hollywood members of the Communist party] wanted to be martyrs. You have to remember, and this is awful to say, a lot of them [party members] weren't very good at what they did. This [the blacklist] justified their not getting a job. That's the other side of it.

You mean a lot of the Ten —

No. Not the Ten.

A lot of the blacklisted people?

Yes. Some of them hadn't worked in ages. They were lousy actors and writers. But it didn't matter; they were decent people.

Why shouldn't they be allowed to be hacks like Harry Kurnitz?

Yes. But they shouldn't have pushed for the First Amendment, which didn't cover the situation.

How did you find out that you were blacklisted?

I know the specific incident, which concerns Jerry Robbins. He had asked me to do a musical [on Broadway] and I started to work on one. I did an outline; the title was Look Ma, I'm Dancing . It was about the ballet.

I was going to a terrible analyst then, Theodor Reik, who was very famous.[*] He said, "Oh, you mustn't do musicals." So I said, "Jerry, I can't do it," and I walked out on him. He [Robbins] was furious with me. I signed away the rights.

They did make a musical out of it. Anyway, later Paramount wanted to make a film of it, so Jerry asked me if I wanted to write the screenplay. I said yes. Suddenly "Swifty" called me and he said, "You're out." I said, "Why?"

* Eminent psychoanalyst Theodor Reik wrote many influential books, including From Thirty Years with Freud, Masochism in Modern Man, Psychology of Sex Relations, Listening with the Third Ear, Fragment of a Great Confession, The Secret Self: Psychoanalytic Experiences in Life and Literature, and Myth and Guilt .

He said, "They say you want too much money." I said, "How much did you ask for?" He said, "I didn't ask for anything yet."

There was a man I knew, Paramount's story editor, who shall remain nameless, who called and told me [I was blacklisted]. I said to this man, "Now we've really got them. We can break the blacklist. This is the perfect thing. They claim they are doing it on the money, and no money has been asked for. We can break the blacklist. I'll sue." He said, "I can't testify." I said, "Why?" He said, "My job."

I wanted to go to Europe but I didn't have a passport. Jerry got me a lawyer, only I didn't know that the lawyer [was connected] to the FBI. I have an overdeveloped sense of morality, which saved me. The lawyer said, "Now you have to tell me everything, in order to get a passport." He grilled me for hours. But there were certain things he wanted to know about [that bothered me]. For example, the Soviet-American friendship affair at the Waldorf. He said, "Who was there?" I said, "You can look in Life magazine." He said, "No, you tell me." I said, "No, I don't want to. You look it up." He knew I was in a Marxist study group in Hollywood. He said, "Who else was in your group?" I said, "I'm not going to tell you." He said, "I'm your lawyer." I said, "I don't care." Luckily.

Finally, the lawyer said the best thing for me to do was to call the State Department, which I did for three months. I'd call them and they'd say, "Your name is on page so and so of this issue of the Daily Worker . Can you tell us what it says?" There would be a review of Home of the Brave, let's say. This went on for three months until finally the State Department man said to me, "Write and explain your feelings about everything." They already knew all the things that I'd given money, and my name, to, but I wrote down what I felt. . . ."

My lawyer said, "Now fix it up. . . ." I said, "I'm going to send it in just like this." He said, "It's too idiosyncratic." It was. But what's interesting is, I sent it in on a Friday, and on a Monday the passport arrived. On Wednesday I was sailing for Europe, and there was a telegram delivered to the boat from Metro offering me a job. That's how closely they worked [together].

After all that, why, at that point, did you leave —

Oh, I was young. Why not go to Europe? I was set to go to Europe. I had no place to live here anyway and I had made up my mind, so I went. And it was fun.

They gave me a passport only for six months, and when I crossed the border with that, the looks I got! In Europe they told me to go to Tangiers, since the list hadn't caught up with people there yet. In Tangiers, the guy at the consulate was being driven out—it was a shame, you know, how McCarthy decimated the foreign service—and he renewed the passport and gave

me a number 33, a diplomatic number. I've never forgotten that. Consequently, I got right through any border.

How long were you in Europe for?

Oh, about a year and a half.

Did you do any film work there?

I had an experience which is too long [to recount], with Sam Spiegel, writing a picture for [Marlon] Brando and [Ingrid] Bergman. It was a hilarious experience. But I don't really want to go into it.

It never came to pass?

No, Spiegel quit paying me.[*] I was going to sue, because I needed the money. My lawyer said to me, "Oh, it's an open-and-shut case. But the line of credit for Sam Spiegel goes around Rockefeller Center, so forget it." So I wrote a play, Time of the Cuckoo, and came home.

Did you meet a fraternity of people over in Europe who were blacklisted?

I have never been involved with people in the theater or in pictures. My friends are largely not in what's called "the business." And over there, they weren't. I met a very diversified group of people, had a wonderful time learning about Europe and about life in Europe.

It was easy to get by. We went to Tangiers, a group of us, people I met in Spain who didn't speak much English; I didn't speak much Spanish. We had fun. You know how we started the day? We'd [each] take $25—now, in those days Morocco or Tangiers was an international city, seven powers, with seven different currencies—so if you worked fast enough, running up and down the street, you could exchange that $25 and make $25. That was enough for the day. So you had your stake of $25 in your pocket and $25 to spend. Then the next day, you did it again. I had no responsibilities. I had no cares.

Were you in touch with what was going on back in the States?

Through friends. In Paris I had a great friend named Ellen Adler, Stella Adler's daughter. She and Brando were having an affair and were very close (and still are). I remember meeting them one day and saying to Marlon, "Well, [Elia] Kazan really topped off everybody," because Kazan had taken out an ad in the New York Times defending himself [for cooperating with the House Un-American Activities Committee]. Marlon said, "You're a shit." I said, "Get the Times and see it." Well, he did, and [then] what did Marion do? That big liberal. Went back to the United States and made On the Waterfront [1954], which is an apology for informing. That's what the picture is about—made by two informers, "Gadge" [Kazan] and [screenwriter] Budd Schulberg.

Actors rationalize. Understandable, and I say—okay. But don't try to make yourself out a hero when doing something you know is scummy.

* Spiegel was a notorious welsher, as is recounted in The Hustons by Lawrence Grobel and in other sources.

When you came back and put on Time of the Cuckoo, were you theoretically turning your back on film?

Yes.

I assume you had nothing to do with the film version directed by David Lean, Summertime.

I did the original screenplay.

You did?

Then Kate [Hepburn] came along and Lean was absolutely bewitched by her and they rewrote it. Oh, the credit says, "H. E. Bates," but they rewrote it.[*] She said to me, "I wouldn't give you ten men for any one woman. . . ." She threw out the meat of the play. The whole second act, she threw out.

Which is?

The man dumps the woman! He says to her, "You can only be sure of something you can touch. . . ." There's a whole plot subtext about the materialism of Americans. Kate's character is so complaining and mistrustful that finally he has had it with her. Then she learns—the beginning of a glimmer—that maybe she should go with her emotions more and not be so mistrustful. But it's too late. He has already kicked her out.

Kate's feeling was that you had written something that was antifeminist—

Not antifeminist! She, Kate Hepburn, is a very bossy, humorless lady. She has a sense of wit, but no sense of humor whatsoever. I like her, she's interesting, she's an original. But she wants to push everybody around, and nobody is going to tell Kate Hepburn anything! Including David Lean. I don't like that movie.

I don't think it is very good at all .

Terrible movie. She's awful [in it]. When the man tries to kiss this woman, suddenly she looks like she's going to have a catalyptic fit. Why? Over a kiss? For God's sake! Awful movie!

Why would she do something like that to herself?

She thinks it [Summertime ] is wonderful. She came back after shooting the movie, invited me over, and said, "Well, you may not like it, but I'm brilliant." And she was not kidding. That's why I say she has no sense of humor. Anybody who can say that with a straight face is humorless.

How could they justify removing your name from the screenplay credit?

Because I didn't want it on. It [the screenplay] was awful.

But it was your own play!

You have no say at all. Don't you understand?! No writer has any say about a movie! You can argue, but you can't say. They have the say. That's why they don't like writers. Because they wish they [themselves] could write. That really is why. They think, now they'll really fix you . . . now, we'll fix you . . . we'll make it ours .

How did your next film, Anastasia [1956], originate?

* Director Lean is co-credited, with H. E. Bates, for the screenplay.

Litvak asked me to do it and I said to him, on one condition. I said, "Tell it like it's a fairy tale. If you're going to do it seriously, I don't want to do it." He said, "No, no, no. Any way you want."

There were two things about that picture that I am very proud of. The big recognition scene of the empress is one. You know, originally Anastasia was a French play, and when they did it in England, they changed it; then when they did it in New York, they changed it again. I never believed the recognition scene. She always came up with some piece of [obvious] evidence. And I thought of the bit where Anastasia had this nervous cough and during the recognition scene, she has to cough. The empress says to her, "Take care of your cold," and she says, "I don't have a cold." The empress says, "Why are you coughing?" she say, "I always cough when I'm nervous." Ah! My long lost! I thought that was a very good piece of business.

Anyway, Ingrid couldn't get a job to save her life. But we wanted her [for the part], and this is where Litvak was terrific. Fox said, "Uh-uh, she's persona non grata." And Litvak says, "I won't make the movie without her." Fox said, "Well, tell her to come to America and we'll test the women's clubs, the Veterans of Foreign Wars . . ." Ingrid said, "I won't." She said (and this is where she was terrific too), "When I go, I'll go because I want to, as an actress, and either you want me as an actress or you don't." So they took her.

But they got Helen Hayes to play the empress to make Ingrid Bergman kosher. I remember I had not met Helen Hayes, and when I did, she said, "Oh, forgive me!" Because she was not an empress. She could play Victoria, a middle-class woman, but the Danish empress was not middle-class.

How about Litvak? Was he articulate at all in terms of script? Was he involved in the development?

In a way. There was always a battle with him. I had a much more interesting opening, I thought. I wanted this deranged character wandering around in a lower subterranean walk near the Seine; she hears music, and from her vantage point you look into the Seine. There's a piano playing there. She dives in, and drowns, presumably.

Well, he wanted this Russian Easter scene because he's Russian and he loved the Russian Easter. He said, "There's such a beautiful church in Paris; we'll photograph it there." So I gave up the fight. Then, typically, they wouldn't allow him to photograph there. So we went to Nice because they had some kind of cockamamie Russian church there. Then they had to build a facsimile of it in London, and, of course, the whole thing cost a fortune for that ridiculous opening.

We had battles, like: He would say, "She can't say, 'I don't.' She has to say, 'I do not.' " I'd say, "No, she can't say, 'I do not.' She has to say, 'I don't'." I would say, "Tola, you don't speak English, you don't understand about colloquial English . . ."

Litvak chickened out with the ending really, because there is [supposed to

be] a scene with the empress—after Anastasia has run off with the Yul Brynner character—where they say, "But what shall we tell everybody? They're waiting to hear . . ." I wanted the empress to look right at the camera and say, "Tell them the show is over. Go home." That would say, "This is entertainment." But when she says it [in the film], she doesn't look at the camera.

I'm surprised you could write films out in the open, in the 1950s, when the blacklist was still operative .

I never went near Los Angeles. Anastasia was Litvak and [producer] Buddy Adler. It was made in London and in Paris.

You have to realize the studios only wanted what was expedient. They had no politics; they didn't care. Again, later on, I was asked to sign something. Metro had the rights to any twenty of Irving Berlin's songs, and he was going to write five new ones for a movie. He wanted me—this was for the Arthur Freed unit—to write an original musical. They gave me an incredible deal, a lot of money, and I also had sixteen weeks off to direct because Stephen Sondheim and I had written a musical called Anyone Can Whistle .

Again I refused to sign. I remember Lazar saying, "You have to sign something . Write anything you want." You're not going to believe this, but I wrote, "I am not a member of the newsboys' shoeshine unit, nor have I ever bee . . ." That was enough. (Laughs .)

Did you ever go to Los Angeles again?

What for? Maybe I might've gone there on a visit, but I didn't work there. I haven't written there since '47.

How about Bonjour Tristesse? Also developed and filmed entirely outside Hollywood?

Wrote in New York and Paris. Made in Paris and London.

Bonjour Tristesse was a miscalculation. I needed money and I was doing West Side Story, which I thought would run three months. So I thought, "Well, I'll get some money from doing this thing with [Otto] Preminger," only it all went into taxes because West Side Story turned out to be a hit.

In Paris, Preminger introduced me to Jean Seberg, who was a shrewd cookie, I don't care what they say about her. Then he had Saint Joan [1957] run for me when I got back to New York. I sent him a cable: "I beg you to get rid of Jean Seberg. She will ruin you, herself, me, the picture, everything." He wouldn't. We had lunch at "21" and he bet me a thousand dollars that it would work. I said, "I'll bet you five dollars." He sent me a five-dollar gold piece after the picture opened. It was awful.

It was a picture about French people with Jean Seberg, Deborah Kerr, and David Niven. There's such a thing as behavior . Also, it's a very slight, ironic story, and that's the way I tried to write it. But Otto, whom I liked, was a heavy-handed Austrian, and he tried to make it so melodramatic.

Françoise Sagan was very heavily overrated. She had a kind of delicate French cynical look at love, and that's what you had to understand. Litvak,

whom I adored, wanted me to do [another Françoise Sagan novel,] Aimezvous Brahms? I said, "Forget her, it won't work. She got by once. Don't try it twice."

Did Preminger involve himself in the script of Bonjour Tristesse?

He left me alone totally. But then the way he shot it, it was ghastly.

Do you have any input on the film adaptations of your two Broadway hits, Gypsy [1962] and West Side Story [1961]?

West Side Story —artistically, I think, they never handled the problem. What are these boys doing—a tour jeté down the street!? The key to it was the decor. You cannot have ballet, I believe, in a realistic setting. They might have tried taking a New York street and stripping it of every bit of set dressing so it would be real but not real . Then I think there would have been more of a chance for the dancing. But the dance on the roof is too like Arthur Freed and company. And the performances are lousy.

"Krupke" was my idea, and Lenny [Bernstein] and Steve [Sondheim] and Jerry [Robbins] didn't want it in the original. I Sold it to them on the snobbish basis of it being like the porter scene in Shakespeare. For the movie they thought, "We're not going to interrupt the drama to have this jokey number . . ." So they put it up front where it didn't work. I don't remember much else about the movie. I didn't like it.

And Gypsy, you feel . . . ?

Gypsy was the worst. She [Rosalind Russell] was so awful. She shouldn't have been in it. It should have been Judy Garland. That's who we wanted, but they wouldn't take a chance on her. The reason was, when she did A Star is Born [1954], her weight went up and down. Well, in this picture, which covers so much time, it didn't matter if her weight went up and down. But that was their reasoning. Idiots!

They asked me to do the screenplay. When I found out it was [director] Mervyn LeRoy and Rosalind Russell, I said no.

You don't seem to have had much luck with your screen career, whether the films were original or adaptations—

They fired me from The Way We Were! They got, I couldn't keep track of them, eleven writers, including [Dalton] Trumbo. They asked two friends of mine, Paddy Chayefsky and Herb Gardner, who told them to go fuck themselves—that was the Eastern Mafia against the West.

They're so scurvy. I had gotten [director] Sydney Pollack the job. [Producer] Ray [Stark] didn't want him. I talked them into it. Then Sydney got Redford. Sidney never let me meet Redford; that's the way they play these games. Sidney said, "He [Redford] is not satisfied. . . ." I said, "Well, let me talk to him to find out what he is dissatisfied with. . . ." He said, "Well, I had a meeting with him. I'll give you this cassette which he gave to me. . . ." What it boiled down to was Redford finally saying, "Well, her part is bigger!"

Then Sydney called me up one day and said, "I have to tell you that Ray

is going to fire you." I said, "Well, Sydney, you're the director and you're my friend . . ." He said, "Well, there's nothing I can do." Half an hour later, Ray called. He said, "I have to tell you Sydney's going to fire you. . . ." So they fired me. Then they started shooting. When they got in terrible trouble, they called me back.

By that time I was over the hurt and the agony, and I said, "I'll come out there and try to fix it. But if you don't like what I'm doing, I'm leaving instantly." They were very nice, but it was all very cold. Only Barbra [Streisand] and I were fine together. He glared at me, Redford. And Pollack, when they had a rough cut of the picture in New York, we sat with the cutter afterward, and Sydney cried that it was so terrible. You don't hear about that anymore. Now it's his great masterpiece and all this kind of stuff.

Who saved it? The editor?

His [Pollack's] work wasn't that terrible. Not that I think he did a very good job. They cut the big scene out of the picture! The scene where the Redford character says to her, "The studio says I have a subversive wife and they'll fire me unless you inform," and she says, "Well, there's a simple solution. We get a divorce. Then you don't have a subversive wife." They shot the original, but they cut it out. Now, at the beginning of the scene all she says is "The simple solution is we get a divorce. . . ." You don't know anything about informing.

How could they justify that?

They said, we want a romance, not a political picture. The picture was an enormous success. That's the justification.

Sydney didn't have anything to do with that. At that time it was in Ray's hands; Sydney Pollack didn't have the power then. Ray had the final control. Ray had a screening in San Francisco, which to their surprise was a smash. But after that—I don't know whether it's true or not—Ray said the exhibitors didn't want so much politics [in the movie], so they cut a lot out. They emphasized the romance, and there you are. But they all play these games. . . .

There's been so much talk of a sequel. Will there ever be one?

It is very doubtful. I did another script, ages ago. There was all this stuff in the press about a sequel, and actually Redford and I have sat here having a lot of talks about it. But he's such a weasel. It turns out he won't do it because Ray Stark would produce it and he hates Ray. It's a whole long story with Redford. He's impossible, egocentric.

Here's why it will never happen. First of all, they [Redford and Streisand] are too old. Also, they won't agree. One agrees, the other one won't. Then Sydney Pollack is busy keeping them separate and together. Then this one hates that one. It's such intrigue.

I gather The Turning Point was equally disappointing, for you, even though you were nominated for an Academy Award for Best Screenplay .

I was on the set with that picture because I was co-producer until my dear

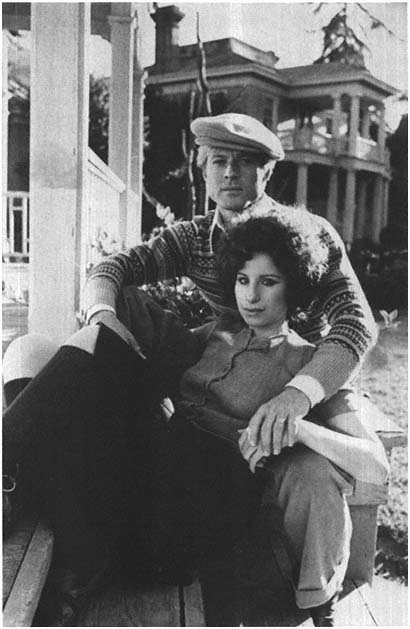

Robert Redford and Barbra Streisand in a publicity pose for the blacklist-era Hollywood

motion picture The Way We Were . Writer Arthur Laurents adapted the screenplay

from his own novel.

friend Herbert Ross asked me to leave.[*] I said why. He said. "Well, you're not only a good writer, you're a good director. You make me nervous." So I said okay and left.

There was a whole gay subplot that was subsequently dropped, wasn't there?

It wasn't a subtext. It was a very skillful handling of the gay issue, I thought. It was absolutely subverted. Not by the studio, but by Herb Ross, and his wife [former ballerina Nora Kaye, the executive producer of The Turning Point ], who was an old girlfriend of mine, for personal reasons. Let's let it go at that. It was shameful.

In the movie the whole plot with Shirley MacLaine and her husband [Wayne, played by Tom Skerritt] doesn't come up until the last scene, this whole business about him turning out to be gay. You wonder, "Wait a minute, what is this? . . ." Well, it was in the beginning of the picture, and there were scenes—[especially one] crucial scene—that were not shot. I can say to you, "Oh, what you didn't see that was in [the script], and you would say, "That's all well for you to say, I can only go by what I saw. . . ."

If you do a play, it's not going to be totally the way you want it to be. Nothing is totally the way you want it to be. First of all, you're not that good yourself. But seeing it all [done the way you have written it] is on a percentage basis, and what you stand a chance of seeing in the theater is so much higher [a percentage] than what you stand a chance of seeing in the movies. They cut it out. They don't give it a chance.

At least you seem to have a pretty good batting average when it comes to seeing the scripts that you have been paid to write actually get produced .

Well, there is unproduced stuff. There are three screenplays—counting They Way We Were sequel. They were paid for.

What are the other two?

One of them was an adaptation of a play of mine called The Endplay, a wonderful screenplay, the best I ever did. But the hero is gay . . . and nowadays—forget it, it'll never be made.

The other one was interesting. This was where I chickened out. I had a deal with Orion, to write and direct, and at the last minute I quit. Because I just could not face all that time on a movie. I couldn't deal with the business end and all the people.

It was called After Love, about that stage in a marriage when the marriage is no longer passionate. That is the danger point. What happens? It's not that they don't love each other, it" that they don't want to screw on the kitchen table. What do they do then? That's what it was about.

* Film director Herb Ross was "musical director" when Laurents staged I Can Get It for You Wholesale on Broadway in 1962.

It doesn't seem as if any Hollywood project has turned out for you the way you envisioned it .

No, no. How could it?

Did any of your screenplays get filmed the way you wrote them, or close to the way you wrote them?

No.

Do any of them give you pride or gratification?

Moments in them. I don't think too much about it.

I like going to the movies. I call them "movies," not "films." There are very few of what I call "films." Moonstruck [1987], which I saw recently, is a real Hollywood movie-movie. You come out joyous, dancing. Romance?—the best. The John Patrick Shanley screenplay is wonderful, very clever. But it is not real. In my terms I can't call it a "film." Though it's a helluva "movie."

It is like minor Capra .

Oh, I never liked Capra. I thought he was saccharine.

I think of him because of all the time he gave to his minor characters .

No, the characters [in Moonstruck ] are fresh. Things like It's a Wonderful Life [1946] are such bullshit. It was bullshit at the time. Lady for a Day [1933]—such banal, saccharine stuff. Maybe they got by with it, then. Somebody wanted me to direct a musical of It's a Wonderful Life, once. That wouldn't stand a chance! People have grown up some; they're not twenty yet, but at least they are eighteen; they know better. It isn't that I don't believe in optimism. I'm an optimist. But when the little man gets up in the Senate [in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939], it's either hypocrisy or cynicism to think they won't cut his head off—who are they kidding? Everything has to be based, at least, in emotional reality, and there is no reality in Capra.

It's interesting to hear you say that, because your stories have that emotional reality. For one thing, so many of the films, in particular, are about cross-class or cross-cultural romance—perhaps influenced by your brief participation in a Marxist study group .

That's not Marxist. That's just life.

It's how Arthur Laurents perceives life. Not everybody perceives it as you do .

I know you—you're looking, again, for too much cause and effect from specifics. You know what I mainly learned from that Marxist study group? How to read a newspaper. I'm not kidding. To see what's behind the news.

I don't mean the study group overtly influenced you, per se, but I wonder why is it that your films are so often about romances between people from different strata?

Because of my age. I am a Jewish boy from Brooklyn who came up against anti-Semitism. That has an enormous effect on your life. It does. That makes you very aware and, at a [certain] time, overly sensitive. I got rid of it [the

sensitiveness] in Home of the Brave . I wrote that out of myself. But you are always aware.

Certainly I was influenced by Marxism. I have a thing about injustice and the underdog and a resentment against people who were born with a silver spoon—I don't resent them having the money, I resent them thinking therefore they deserve the world.

You weren't born with a silver spoon?

No, no. My parents were middle-middle class.

Then how did you become such an incurable romantic?

Isn't everyone? Everybody wants love. That's one of the major things that life is about. Freud says life is about work and love, but I think there's something else. There's some kind of—for want of a better word, I'll call it spirituality, which you must have. Work and love are the main things in the world.

By work I don't mean success. Nor do I mean achievement. I mean doing work that you like. That's what it is all about. Even if you're not so hot at it, writing is better than selling women's clothing at Bloomingdale's. I sold towels at Bloomingdale's. I hated it. When they fired me, I cried, because it was rejection. But to be able to do something you like, even if you're not very good at it, that's terrific.

It seems to me that, at this point in your life, you almost regret the time you spent writing motion pictures .

No! You can't regret what you've done; you can only regret what you didn't do. You learn all the time. So what?

But it also sounds as though you'd be interested in writing another movie if the right combination of circumstances came along .

It's possible, but it's highly improbable. They want to do Gypsy again. But Steve [Sondheim] and I don't want Gypsy done as a movie. We'd love to have Bette Midler do it on the stage and then film it as a videocassette, for the record. Ray Stark called the other day. Everybody's calling. They're desperate for material. But if you give them the material, off goes your head and your balls and your feet and your hands. And if you've got one eye left, you're lucky.