Modernist Photography and the Group f.64

Therese Thau Heyman

In California, modernism gained its first impetus among groups of like-minded artists who gathered to propound their ideas. Traveling exhibitions, publications, and catalogues kept the relatively remote Californians in touch with advanced art ideas from Europe. Among artists, photographers were at the fore in shaping the state's distinctively modern image. This fact will surprise no one who has taken time to consider the essential modernism of photography as a medium, or has taken the opportunity to reflect on the close association of the medium with this particular place. Photography played a decisive role in California culture beginning in the Gold Rush days, and it has continued to do so throughout the twentieth century. Still, the history of photography in the United States underwent a transformation in the early 1930s, and this change was recognized and named by a group of California photographers who sought a new, essentially modernist, perspective through their art.

John Paul Edwards, a pictorialist photographer in the thirties, recalled the spirit of change that distinguished these years: "It was in August 1932 that a group of photographic purists met informally in a fellow-worker's studio for a discussion of the modern movement in photography."[1] For Edwards and his colleagues, like Edward Weston, modernist ideas, although intriguing, were identified mainly with fine arts issues that related to other media. Debates about modernist painting, for example, tended to revolve around representational issues of clear, flat color and the picture plane. By contrast, photographers saw reality as palpably modern. Still-life objects appeared architectural, even heroic, in scale.

The New Deal, Reporting, and Straight Photography

In late 1932, even before Franklin D. Roosevelt assumed the presidency, advisers were framing programs to lift the country out of the debilitating economic depression. The New Deal, promised during Roosevelt's campaign, represented a new philosophy of

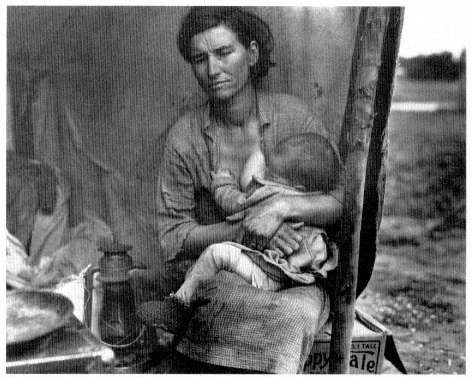

Figure 91

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California , 1936. Courtesy

The Oakland Museum, Dorothea Lange Collection, gift of Paul S. Taylor.

government and drew the administration directly into the theoretical and aesthetic preserve of contemporary life. An important step toward ending the economic decline was the creation of agencies to assist thousands of displaced workers and rural families.

To gain public and congressional support, proponents of any aid program had to state its rationale clearly and memorably. Urban voters and elected officials had to be educated about conditions in rural areas where they did not venture. Roosevelt turned for help to two Columbia University academics, Rexford Tugwell and Roy Stryker, who were assembling cultural histories and were beginning to realize that the almost century-old medium of photography could transform written government reports into dynamic evidence. Photography, intensifying the impact of facts, could perhaps provide the novel means to gain sympathetic and immediate political attention. Photography was considered to be a truthful record, an independent eye viewing an undeniable reality.

The photographs that eventually accompanied reports of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in the late 1930s were direct, clear, and in many respects like the work of the photographers who had formed Group f.64 in the San Francisco Bay Area the year of Roosevelt's election. Although the FSA work was decidedly not "art," its elements of composition and selection were essential to effective reporting. This photographic work was accomplished at a time when it was assumed that the photographer found—that is, did not invent—the reality whose image he captured, an approach that soon came to be called "documentary photography." Most people believed that photographs could constitute accurate records of events and conditions, and they had sound reasons for their belief (Fig. 91).

Photographic veracity had a long-established tradition in the United States. Nineteenth-century photographers had created a picture of the American West that confirmed the stories of mountainous scenes inspiring wonder and awe. Their views verified the astonishing news that gold had been discovered in Northern California and validated for distant families the safe arrival of hordes of adventurers who had gone west to make their fortune.

By the turn of the century, the government-commissioned photographic surveys of federal land holdings were complete, published, and widely available. Photography had become a populist phenomenon, practiced by a select and growing amateur group that accepted these 20-by-24-inch glass-plate exploration records and thousands of pocket-sized portraits as the plainspoken and truthful language of pictures. Photography preserved memory, created records, validated personal genealogies, and stopped time in ways heretofore not accessible to the average person. When in the late nineteenth century the invention of the handheld camera gave photography to the populace at large, its place in the American social fabric was already ingrained.

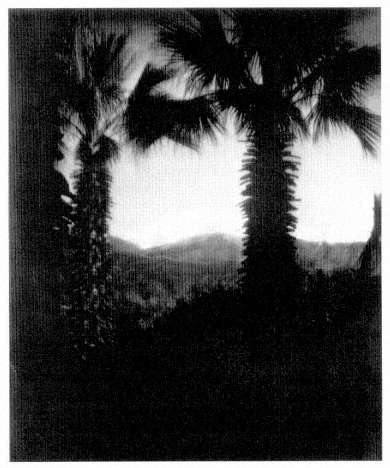

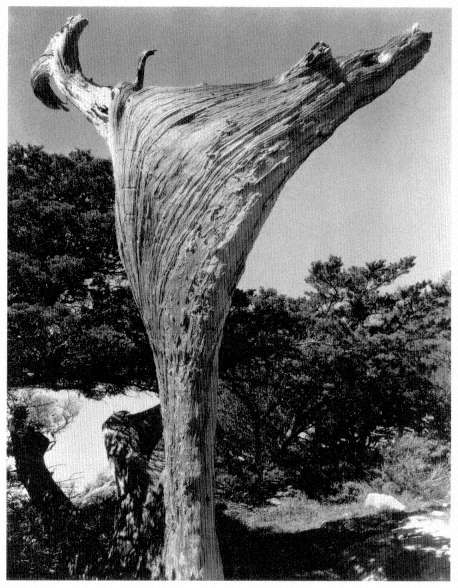

Photographers began to expand the basic syntax of representation and validation to create an elegant form of romantic photographic language, one they hoped would be fully recognizable as fine art (Fig. 92). Their painterly visions, embodied in soft-focus, manipulated prints and tonalist studies, suggested quasi-literary narratives. They hand-colored surfaces and used inky pigments on textured matte papers to achieve self-consciously artistic images conveying personal and interpretive content. Their images created a busy interchange among camera-dub juries.[2] In the West large numbers of pictorialist photographers (Fig. 93) continued to take prizes at Bay Area salons as Roosevelt was preparing to take the oath of office. In the next few years, however, a revolution in photography started to brew, one that was more widespread and potent than has been recognized.

Pictorialist thinking and theory were at their most articulate in the mid-1920s. William Mortensen, a leading pictorialist, later explained, "The business of a work of art is to make an effect, not to report a fact." Creating effects was pictorialism's high calling. Mortensen went on: "Photography must learn to avail itself of selection to the same comprehensive degree that older arts do: by this it must stand or fall as art. Otherwise... the camera has no more artistic potentiality than a gas-meter."[3]

Figure 92

Karl Struss, In the Southland, Mt. Baldy, California ,

ca. 1921. The Oakland Museum, gift of the Knott Fund.

Such claims, outrageous to some, fired a debate that soon became acrimonious, and Bay Area photographers who engaged in it did not simply return to recording facts. They countered old-style pictorialism with a revolutionary style—"seeing straight." The lines were drawn: one observer noted that Edward Weston had "dared more than the legion of brittle sophisticates and polished romanticists ever dreamed."[4]

Eight or nine years before Group f. 64 was formed, Weston had turned away from pictorial practices, proclaiming his change in aesthetics in a series of briefly stated technical steps in his daybooks. He minced no words in this 1930 entry:

Figure 93

Anne Brigman, The Storm Tree , 1912. The Oakland

Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Willard M. Knott.

I wrote an article, published this July with examples of my work in Camera Craft , a photo magazine which offers its readers just what they want .... I tempered my words, fearing the editor might not stand up under full blast. But seeing some unusually awful reproductions in the same issue by one Boris, with a laudatory article by the editor, I spent an hour writing him my mind. These cheap abortions which need no description other than their titles, "Pray," "Greek Slave," "Orphans," "Unlucky Day," have nothing to do with Art, nor Life, nor Photography. So I not very gently explained. But why did I waste my time? I know the Editor's policy, his outlook from his writing and magazine in general: backing my work and opinions, his publication would fail!

I am in a mood to stir things up![5]

As a reformed pictorialist, Weston often led the attack against shimmer and simper, crusading to attain the "straight" image Willard Van Dyke came to call "pure photography." Earlier in 1927, Weston had promised:

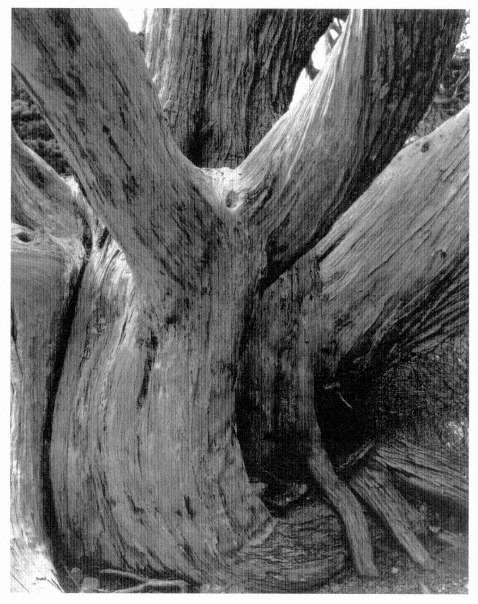

Figure 94

Edward Weston, Monterey Cypress , 1932. The Oakland

Museum, Prints and Photo Fund purchase. © 1981 Center

for Creative Photography, University of Arizona Board of Regents.

Sometime I want to give an exhibit printed on glossy paper. This shall be my gesture of disapproval for those who try to hide their weakness in "arty" presentation. [This long-held plan received fresh impetus after he viewed the International Salon of Photography at Exposition Park in Los Angeles.] Unable to definitely use Form these pictorialists resort to artistic printing....

That exhibit, excepting two or three prints, if reprinted on glossy paper, stripped of all subterfuge, would no longer interest even those who now respond ....

Those "pictorialists" were deadly serious, I grant,—so serious that the result was often comic. I took Brett, hoping to find material for discussion: there was nothing to discuss .... After noting the numbers of four photographs that had some value I referred to the catalogue, finding that each one was by a Japanese. Perhaps my exhibit in the Japanese colony has borne some fruit,—I could feel my influence [Fig. 94].[6]

None of the move away from pictorialism occurred in isolation from the other arts during these years. Important exhibitions of Bauhaus abstract art at the Oakland Art Gallery included a Lyonel Feininger solo show (April-May 1930), a show of German posters (September 1930)—which apparently included photographic material—and a Blue Four exhibition (1931). Galka Scheyer,[7] who identified herself on gallery letterhead as the "foreign representative of the Oakland Art Gallery," actively promoted German expressionist painters in the Bay Area; and in 1930 Rudolph Schindler also spoke at the Art Gallery on the relationship of architecture to the Bauhaus show.

The nexus from which change proceeded in Bay Area photography may well have been the activities of Galka Scheyer. She visited Weston in Carmel on more than one occasion in the late 1920s, and in 1930 he noted that she was a "dynamo of energy"; her insight was "of unusual clarity"; she had "an ability to express herself in words, brilliantly.... She is an ideal 'go between' for the artist and his public."[8] But we cannot know whether to attribute to Scheyer the full awareness of a new aesthetic for photography. Weston, in any event, saw himself in the forefront of a revolution. "Yesterday [March 7, 1930] I made photographic history: for I have every reason and belief that two negatives of kelp done in the morning will someday be sought as examples of my finest expression and understanding."[9]

Weston's diary entries allowed him to date his artistic growth, confident of his own originality, and he took on the pictorialists at every turn: "I have already made a showing, and hope that my next exhibit will be on glossy paper. What a storm it will arouse from the 'Salon Pictorialists.' . . . Now all reactions on every plane must come directly from the original seeing of the thing, no secondhand emotion from exquisite paper surfaces or color: only rhythm, form and perfect detail to consider."[10]

The Origin of Group F.64

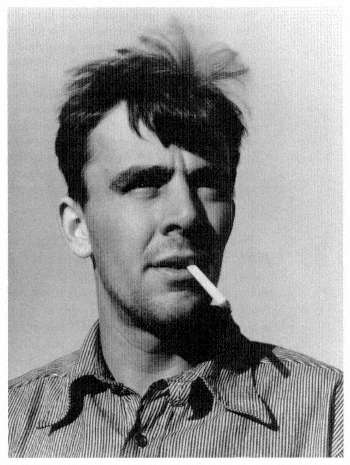

Group f. 64 was initiated by Willard Van Dyke and his friend Preston Holder (Fig. 95), of whom Van Dyke wrote:

Figure 95

Willard Van Dyke, Preston Holder , ca. 1934.

Collection of Barbara M. Van Dyke.

[He] saw things much the way I did. I had gone back to the University [of California at Berkeley] after five years [in 1931] to take a few courses that interested me. A student in one of the courses happened to see a few of my photographs in a local bookstore... and introduced himself. We became close friends, drank wine and read Hart Crane and Robinson Jeffers together. Of course we both had blue-papered covers of James Joyce's Ulysses and carried them everywhere as a protest against the Philistines.[11]

Holder soon acquired a camera, and the two men took trips:

After one afternoon of art and wine... Preston suggested that we ought to form a group of like-minded Western photographers and begin to exhibit our work together. I was excited about the idea; it appeared to me that this would provide an opportunity to make a strong group statement about our work .... I, for one, felt that it was time for the Eastern establishment to acknowledge our existence.[12]

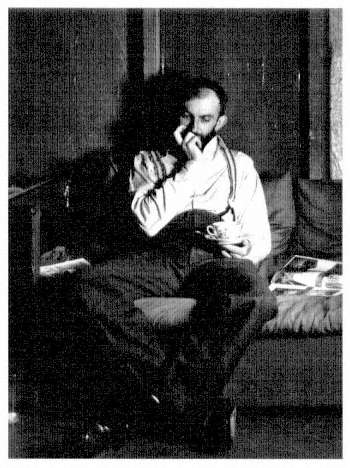

Figure 96

Willard Van Dyke, Ansel Adams at 683 Brockhurst , ca. 1933.

The Oakland Museum, Prints and Photo Fund purchase.

Van Dyke knew that Alfred Stieglitz had been patronizing to Weston when Weston went to New York in 1922. He also believed that Weston's photographs were superior to Paul Strand's, that Imogen Cunningham's plant forms and nudes were very fine, and that Ansel Adams (Fig. 96) was beginning to understand the Sierra Nevada. Not long after the talk with Holder, when Weston was in town and a party was arranged for him at the 683 Brockhurst gallery in Oakland, Van Dyke brought up the question of forming a group. In addition to Weston, Van Dyke, and Holder, the party guests included Ansel Adams, Sonya Noskowiak, Imogen Cunningham, Mary Jeannette and John Paul Edwards, and Henry Swift.

"Here [at 683 Brockhurst] we named the f.64," Van Dyke remembered. "Photography opened a whole new world to me. I was so excited that there were other photographers around this area who saw things much the same way." Several names were tried in the liquid party atmosphere of that first discussion:

We got together one night ... and I presented the idea of our working together. I said besides that I've got a wonderful name for it, U.S. 256 [after the old rapid rectilinear lens that Weston used to get the maximum depth of field and to make his negatives appear sharper]. Well there was this kind of blank look around the room and then Ansel who was the scholar of the group, said, "Oh, you mean in the uniform system 256 equals f 64. But don't you think f 64 would be a better name. Nobody is going to be using the uniform system much longer and besides that beautiful f followed by a 6 and 4," and he drew it out, like that and you could suddenly see the cover of the catalogue or the announcement and the graphics were there and Ansel won.[13]

James Alinder's lively interview with Preston Holder in 1975 includes that photographer's memory of the naming of the group. He describes a drunken ferryboat ride with Van Dyke from San Francisco back to Oakland, during which they talked about how the f would produce nice Bauhaus-inspired graphics. Holder said the group should be called "f/64, because that's what you want to stop down to anyway and that's a good rationale for it, a catchy name and a good symbol."[14]

The Group's Exhibition Statement

Despite the diverse activities of the leading members of Group f.64, they crafted a strong unifying statement, as did other avant-garde art movements. Their six-paragraph proclamation is notice of a revolution. It appeared at the group's first exhibition at the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco and was issued in the name of the group to make its ideas directly available to museum visitors and, more pointedly, to photographers—especially pictorialists, whose style was then still publicly accepted—and to their critics. It was purposely framed in plain language, with few technical terms. It was a rallying cry to the

great number of serious workers in photography whose style and technic does not relate to the métier of the Group .... The members of Group f.64 believe that Photography, as an art-form, must develop along lines defined by the actualities and limitations of the photographic medium, and must always remain independent of ideological conventions of art and aesthetics that are reminiscent of a period and culture antedating the growth of the medium itself.

It is likely that the statement was written and produced by Van Dyke, with help on the wording from Holder. A clue to authorship is the Americanization of "technic," since Van Dyke uses this form in letters to Weston. Van Dyke, particularly in his early writing, shows a clear, precise style that avoided the doctrinaire yet was audacious.[15]

Weston's few references to the group occur in a short chapter that the editor of his daybooks, Nancy Newhall, entitled "F64"; many readers have been led to these two

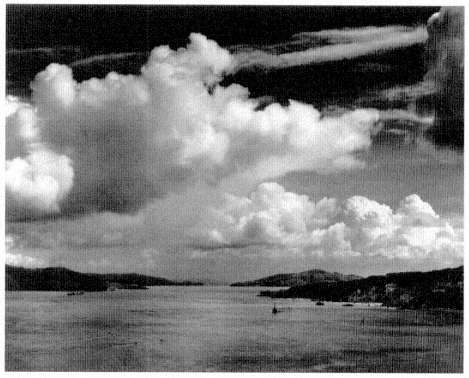

Figure 97

Ansel Adams, The Golden Gate before the Bridge, San Francisco,

California , 1932. The Oakland Museum, gift of the Estate of Helen Johnston.

© 1995 by the Trustees of The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. All rights reserved.

pages. There Weston noted, "Some have expressed astonishment that I should join a group, having gone my own way for years." This short entry has led many later authors to assume that at this time Weston was more preoccupied with personal achievement than with the goals of Group f.64. In his introduction to his solo show in New York in 1932, Weston cautioned, "Too often theories crystallize into academic dullness—bind one in a straitjacket of logic,—of common sense, very common sense."[16] With that, he explained that in an uprooted society the camera can be a means of self-development. If there was one idea that held the group together, it was this belief in the power of photography as a means of personal expression.

As to how well individual members accomplished this goal, opinion varied. Years later, Adams (Fig. 97) remembered: "In the wild heat of formation . . . mutual excitement, wonderful things happen. And then the thermostat goes on. The f 64 group made a great contribution, [an] affirmation of certain basic facts in photography that

would not have been needed if the general level of photography had been high enough."[17] Adams saw Group f. 64 as "an organization of serious photographers without formal ritual of procedure, incorporation, or any of the limiting restrictions of artistic secret societies, Salons, clubs or cliques." The group would accept "any photographer who in the mutual favorable opinion of all of us, evidences a serious attitude, a good straight photographic technique, and an approach that is basically contemporary," admitting that "friendly but frank disagreements exist among us."[18] Surprisingly, Adams named seven photographers who had been considered for membership, among them Consuelo Kanaga and Dorothea Lange (who was not invited to join); in his own gallery show he did not include Sonya Noskowiak.

The Exhibition

The group of photographic friends came together as a loose organization sometime after a solo exhibition of Edward Weston's work opened at the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park in December 1931. The seven original members were Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, John Paul Edwards, Sonya Noskowiak, Henry Swift, Willard Van Dyke, and Edward Weston. They arranged to exhibit their work collectively at the de Young, inviting four other like-minded artists to participate: Preston Holder, Consuelo Kanaga, Alma Lavenson, and Brett Weston.

The exhibition, which opened on November 15, 1932, and was on view for six weeks, was composed of eighty photographs: each of the seven group members showed nine prints (Adams had ten), their guests four apiece. The museum's checklist was arranged by artist, suggesting that the gallery spaces were similarly arranged. Seen together, the images established a varied but mostly singular point of view. For the most part, objects were seen up close, framed by the sky or another neutral background. Nothing was moving, and there was great attention to the finely detailed surface textures of the subjects. There was little in the photographs to suggest either the modern industrial world or the troubles of the times.

Most accounts of Group f. 64 note that it was primarily social and short-lived; that it exhibited only once; that after that first venue the group disbanded and the works were not seen together again; and that the audience was therefore limited to those who saw the show at the de Young Museum between November 15 and December 31, 1932. Yet interviews with these now-famous photographers, their own notes and letters, and newspaper reviews beginning with the exhibition reveal a different history. Hurried notes, a few initials in exhibition lists, and recently discovered letters refer not to one show but to a series. Los Angeles, Portland, Carmel, Seattle, and still other cities are mentioned as venues where the photographs were seen before they were finally returned to the lenders in late 1935. Even with the newly discovered letters from Weston to Van Dyke and Adams's notes, it is still not possible to know precisely how the first show was augmented when it traveled. Reviews suggest a larger show of one hundred works in Portland.

The storm of written protest that soon arose in the pictorialist and camera-club press also suggests that the exhibition had multiple venues; one showing at the de Young would hardly have provoked the number of articles that were eventually published. Furthermore, the group's statement of purpose called for frequent shows. It is therefore more likely that the group owed its impact and the published responses to the photographs and premises of the group to the appearance of the show, or versions of it, in other West Coast cities where photography was an important and current amateur interest.

The San Francisco Chronicle reviewed the exhibition at the de Young Museum on November 27, 1932. Neglecting either to assess the significance of this initial exhibition or to discuss the group's statement, the reviewer nonetheless praised the "beautiful work on view .... These photographers, like other talented brethren of the lens, are admirable portrait artists, imaginative creators of abstract patterns, who look for charm in boats, in scenery, in every small growing thing that is nourished at the bosom of Mother Earth."[19]

An annual report of the Seattle Museum of Art lists a Group f.64 exhibition from October 4 to November 6, 1933.[20] This exhibition apparently went on to the Portland Museum of Art; two printed discussions reviewed f. 64 work as well as that of a complement of Oregon photographers exhibiting at the same time. In November 1933 a reviewer noted in the Spectator that "from the viewpoint of the artist, the display of prints in the downstairs galleries at the Museum of Art is one of the most interesting exhibitions of photographic art ever shown at the museum .... The work of Edward Weston particularly shows fine technical composition and artistic viewpoint .... The entire group seems to feature the objective representation of carefully selected form."[21]

In addition to these northern venues, portions of the Group f.64 exhibition appeared at the 683 Brockhurst gallery and at Mills College in Oakland,[22] at Ansel Adams's Geary Street gallery in San Francisco, and at the Denny-Watrous Gallery in Carmel, as well as in Los Angeles. There is mention of a possible New York venue. Weston, who had shown work in New York, wrote to Van Dyke on January 27, 1933, questioning the wisdom of going there with an exhibition "that may be a bad move or gesture for me to make this year don't you think that the group is a bit hasty in wanting to show this year?"[23]

A New Direction

A confirmed pictorialist, the reviewer Sigismund Blumann, writing in Camera Craft in May 1933, provided the first considered review of Group f.64's premier exhibition:

The name of the organization was intriguing. The show was recommended to us as something new, not as individual work might go but as a concerted effort specifically aimed at exploiting the trend. We went with a determined and preconceived intention of being

amused and, if need be, adversely critical. We came away with several ideals badly bent and not a few opinions wholly destroyed The Group is creating a place for photographic freedom.

... [Y]ou will enjoy these prints. You will be impressed, astounded.[24]

Although Blumann revealed that he preferred the familiar and the romantic view, he clearly recognized a new force abroad in photography.

Blumann's encouraging words were countered, however, by other voices. Albert Jourdan, a little-known and quite bitter photographer from Portland, Oregon, condemned the straight photography movement as unoriginal. In his aptly titled essay "Sidelight #16: The Impurities of Purism," he dismissed Group f.64.[25] He recounted his own initiation into pure photography in 1931, describing how "the carcass" of the "Latter Day Purist" movement, which originated in Germany, was brought "across the Atlantic and the continent, [given] a few shots ... and, very recently, proclaimed ... a 'definite renaissance,"'—an account he concocted out of whole cloth because some German photographers' works were on view in Oakland in 1930. In Jourdan's view, "Moholy-Nagy is one originator of Pure photography, along with other Bauhaus members," all of whom, Jourdan noted, worked before Weston. While it is not surprising that the transmission of European and East Coast ideas to the West Coast would take time (in painting it often did), European photographers recognized that several Americans had taken the lead sometime between 1913 and 1920. That it took Weston eight or nine years to "convert" hardly seems reason for Jourdan to impugn his work or his goals.

Probably because contemporary events overshadowed the activities of artists, most histories have overlooked the subsequent versions of the initial Group f.64 exhibition. Despite the group's marked activity during 1932 and 1933, the newspapers, generally preoccupied with the seriously depressed economy, gave only the briefest attention to announcements about art. Publicity for Group f.64, therefore, may not have been what one would expect. To compound the problem, the newspaper the Carmelite had gone out of business, making it more difficult to give the Denny-Watrous exhibition adequate notice in Carmel, where Weston was based.

In addition to their involvement with Group f.64, members were actively pursuing their own careers. In 1933 Ansel Adams went to New York and had a momentous meeting with Alfred Stieglitz, the acknowledged leader of fine art photography and owner of the influential gallery An American Place. On the West Coast, Willard Van Dyke and Mary Jeanette Edwards had taken on the demanding task of establishing their gallery at 683 Brockhurst in Oakland as a center and forum for West Coast photographers, in an attempt to bring national and specifically East Coast attention to their work. And during the months before the de Young opening, Edward Weston was engaged in the production of his beautiful new book The Art of Edward Weston , which

was on press in late September 1932 and available for signing when the Group f.64 exhibition opened in San Francisco in mid-November. California Arts and Architecture magazine carried a prominent picture endorsement for the book in its November 1932 issue—just the kind of publicity the group would have wanted for its show.

Perhaps the most likely reason for the curious silence about the later six versions of the Group f.64 exhibition can be traced to Lloyd La Page Rollins, then director of the de Young Museum. Although he was the sponsor of Group f.64, the museum's board of directors did not support his championing of photography, and Rollins ran into trouble because of the space photography had come to occupy in the galleries. It seems that he had replaced many of the not-very-distinguished paintings the board had donated to the museum with new photography exhibitions. The board asked him to resign in April 1933, just five months after the opening of the Group f.64 exhibition.

Although the f.64 show was sent to its subsequent venues and was listed in Camera Craft as an exhibition available for travel, both promotional materials for the touring museums and dedication to the project were probably in short supply once Rollins had resigned. In his daybooks Weston had earlier explained that the show would go to the de Young "out of consideration for Rollins," who had requested that the group not open its own gallery to compete with his program. After his departure, however, the issue of competition was moot. Necessity now required a gallery to promote "straight seeing." The first in the Bay Area to take up this challenge was 683 Brockhurst.

The Group's Aesthetics

If we analyze the de Young checklist of the Group f.64 show, we find images of still life; bits of landscape, posts, bones, and sky; a few industrial buildings; portraits; and nudes or figure studies. The subjects were ordinary, yet most had a commanding presence when photographed. The emerging aesthetic proved broader than the group's manifesto, more generous in its means; filters, dodging, and arranging still lifes were all accepted in one case or another.[26] Isolated instances of technical manipulation evidently met the group's ideal of an art form obtained by "simple and direct presentation through purely photographic methods."

Although Group f.64 distanced itself from the pictorialist tradition, at least four of its members had produced fine pictorial work in the 1920s, and three continued to do so until 1931. Their established friendships, moreover, clearly went back to the pictorial days. Roger Sturtevant, a close friend of many Bay Area photographers, remembered a congenial opening in the mid-1920s when Edward Weston was in San Francisco. It drew many photographers, who were themselves photographed there in a series of hilarious pantomimes. Weston and Anne Brigman posed in costume as the father and mother of photography, with the "children"—Roger Sturtevant, Johan Hagemeyer, and Imogen Cunningham—framing them in adulatory, prayerful poses. Roi Partridge, Imogen's husband, took the photographs.[27]

683 Brockhurst

Willard Van Dyke, a central figure in founding Group f.64, continued to provide a focus for Bay Area photography. In 1928, two years after he left the University of California at Berkeley, Van Dyke assisted in making and showing lantern slides for lectures by the much-honored but unconventional tonalist photographer Anne Brigman. Her studio at 683 Brockhurst Street in Oakland was a center of creative activity and a meeting place for artists.

Brigman's ardent love of nature surfaced even in domestic decisions:

When the barn at 683 Brockhurst was remodeled, as a studio, a problem arose in building the bathroom. The only logical place to put it had a lovely tree happily growing in that exact spot ... of course there could be no question of removing the tree. All the carpenters had to do was build the walls around it, provide a hole in the roof for its trunk, and then hang the shower from one of the lower branches. A true daughter of Zeus, Annie never interfered with nature.[28]

Van Dyke and his friend Mary Jeannette Edwards, whom he wanted to marry, had taken over this studio by 1930, intending to establish a gallery for photography. Brig-man had gone to live in Southern California to be near her sister and rented it to them for twelve dollars a month. Van Dyke stated that while he and Mary Jeannette certainly did not consider themselves in competition with Stieglitz, they felt that by establishing a gallery for photographers, they could provide "an atmosphere on the West Coast that could be useful to Western artists. I think . . . our first exhibition, on July 28, 1933, was a retrospective of Edward's [Edward Weston's] work. The prints were displayed in chronological order . . . from 1903 when he began . . . to his most recent photographs."[29]

Although the couple changed little of the charming character of 683, its board-and-batten walls presented an aesthetic problem in the exhibition of photographs. A photographer friend of Mary Jeannette Edward's father, a talented designer, helped to solve it. Van Dyke describes the process: "First he covered the whole surface with monk's cloth ... that he pasted over the wood. Then he brought enough tea paper to cover the surfaces . . . with the gold or silver metallic material. Then he sponged water paint in colors of violet and blue over the tea paper and wiped it lightly before it dried. This left a colored, textured surface with flecks of glowing metal shining through." The gallery in this renovated space, as its stationery stated, was "devoted to contemporary expression in black and white."[30]

Camera Club Notes, a column in Camera Craft , in reporting on the opening exhibition, hailed "this charming little gallery . . . opened by two young people with a splendid enthusiasm for photography. For a long time we have felt that the Pacific Coast is a particularly fertile field . . . that here are many of the finest photographers."[31]

Weston's new landscapes caught the attention of the reviewer, who then listed the gallery owners' future plans for shows by Adolph Dehn, a lithographer; twenty-five prints by Ansel Adams, "well-known for his sympathetic photographs of this city and for his splendid prints of the high Sierra"; and works by Willard Van Dyke and Imogen Cunningham. Van Dyke closed the season with a juried show of what he defiantly called the "First Salon of Pure Photography." He remembered that "Weston laughed at the word, 'pure,' but we all were astounded at the response."[32] The hundreds of works submitted for consideration indicated that many photographers shared the group's ideals, suggesting too that after the period of innovation and diffusion f.64 had had an effect. Many photographers had accepted the premise of unmanipulated image making.

Edward Weston made it possible for Van Dyke to justify continuing in photography and opening the gallery. When Van Dyke told him he had been offered a job as district manager for an oil company, Weston replied, "To work at something just to have financial security could be compared to the life of a cow that spent its whole life filling its belly." Extrapolating from this thought, Van Dyke recalled, "He knew that I had talent but if I decided to go on and develop it, I had to realize it would require sacrifice and uncertainty." Weston referred to this as the decision to "turn down the bitch goddess Success."[33]

Women in Group f.64

The members and associates of Group f.64 were generally well educated in the ways of commercial photography by the early 1930s. They were mainly self-taught, although two were experienced darkroom assistants to more mature photographers (Noskowiak for Weston, Mary Jeannette Edwards for Lange). Their ages in 1932 ranged from forty-nine (Edwards) to twenty-one (Brett Weston), but most were in their thirties or earl), forties. They all tended to accept the authority of Edward Weston's years of photographic experience. And, notably, women were strongly represented among them.

The study of Group f.64 invites speculation about why so many women were empowered through their association with a predominantly male friendship group that might have ideologically subjugated women as darkroom assistants and mere receptors for male creativity.

Very likely the acceptance of women into the group was made possible after World War I by the emergence of the "New Woman," demanding the right to work and vote. As early as 1913 eager women writers explained admiringly that Anne Brigman and Laura Adams, a successful San Francisco portrait photographer, could be independent in photography, as this work was "suitable" for women, needing no large capital outlay, no long schooling or learning beyond the usual education of women. Women's "intuition" was cited as justifying their special talent for portraiture, particularly—it comes as no surprise—of children.[34]

Imogen Cunningham, on her own after European study and schooling in chemistry, began an innovative and provocative series of male nude studies of her husband, Roi Partridge, who was pictured faunlike in settings of the Washington hills and mist-covered lakes. For financial support she also pursued studio portrait work, photographing children and their families, while continuing to keep in touch with the magazines and shows that led the way toward modernism (Fig. 98).[35] Cunningham's direct, no-nonsense personality led to her willful decision in 1934 to go to New York despite Roi's disapproval. The trip resulted in divorce. (Anne Brigman had taken a similar trip, with similar results, in 1910.) Cunningham continued executing portrait commissions to support her twin sons and a slightly older son, all under the age of nine. Perhaps because she assumed these responsibilities, her male colleagues considered her a professional, a fine art photographer, an equal, and a friend. In 1928 Weston sent her a gloriously complimentary letter, telling her that her photographs were the best in the San Francisco salon.[36] Possibly her sense of fun and her sharp wit gave her powerful weapons in any struggle for parity with men in the group. Cunningham was always treated with respect.

Sonya Noskowiak's initial position in the group was as a dependent. Her progression from receptionist in Johan Hagemeyer's Carmel studio, where she met Weston, to Weston's general helper, darkroom assistant, and then model, mistress, and companion is well known. The daybooks chart the circumstances of their relationship as well as Weston's egocentric appreciation of Noskowiak's photographs in January 1930, almost her very first: "A negative of Neil's hands, the back of a chair, and a halved red cabbage. Any one of these I would sign as my own. And I could not give higher praise. She is a surprise."[37]

Consuelo Kanaga was an unusual participant in the f.64 exhibition of 1932. Young, naive, and working on her own for newspapers, she was dependent on her patron and sponsor, Albert Bender, who was also important to the careers of many members of Group f.64. She knew them but was shy, reluctant to become involved. In her letters to Bender she repeats her reservations and doubts.[38] Even her early pictures were of social themes. For example, she made black-and-white photographs illustrating blacks and whites holding hands (Fig. 99). Her 1928 portrait Frances , of a sweet-looking black

Figure 98

Opposite, top : Imogen Cunningham, Mills College Amphitheater ;

ca. 1920. © 1978 The Imogen Cunningham Trust.

Figure 99

Opposite : Consuelo Kanaga, Untitled (Hands) , 1930. The Brooklyn Museum, gift of

Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga through the Lerner-Heller Gallery.

child, was considered out of the ordinary, as the Bay Area black population was then small. Unlike Arnold Genthe, who sought the exotic and alien "other," Kanaga pictures Frances as a child who happens to be black. Kanaga's picture conveyed an innocent message of racial understanding in which potential conflicts are easily resolved. Kanaga was interested in the way black-and-white photography could make social statements; only in passing did she consider photography a fine art.[39]

When Alma Lavenson went to Carmel in 1930 to meet Weston, he urged her to reconsider the soft-focus atmosphere of her prints.[40] She was self-taught, and like the others in Group f.64 she had learned the craft thoroughly. She renovated a childhood playhouse as a darkroom and created photographs by first visualizing them in her mind. She accompanied friends who painted and etched scenes at the Oakland waterfront, photographing that active port. Its warehouse buildings and ships' riggings became a favorite f.64 subject.[41] From the outset, Lavenson's pictures were successful in competitions.[42] Although she did not know other photographers at first, she did subscribe to camera magazines, and she had good equipment; her family, through a successful mercantile business, was well able to afford it. With letters of introduction from Albert Bender, a family friend, she met Imogen Cunningham, Consuelo Kanaga, and Edward Weston. Although her contact with Weston was most significant for her photography, Cunningham had greatest influence on Lavenson's activity as a photographer: "I met her in 1930, somehow or other we became close friends and we remained close friends until she died forty years later. I photographed with her and we travelled together. . .. She never criticized my work, she never praised it."[43]

These remarkable women were acknowledged as peers by their Group f.64 male contemporaries. Only later did a silence come to surround their work—a silence created by exhibition curators, art dealers, and photographic historians in the 1950s. Although Lavenson and Cunningham continued to live and photograph in the Bay Area, they were not singled out for solo shows until their careers were validated by their remarkably long lives. As Cunningham noted, she and other women photographers in their fifties were invisible; only when she reached seventy did she become a celebrity.[44]

Art and Life

The basis of the group's manifesto began with light; its chemical action on sensitized surfaces described the process of photography. Light was the only legitimate medium for photography, and much of the success of an artist photographer lay in controlling it. In the West, light meant sunlight, filtered sunlight—in Weston's case, cheesecloth was stretched like a tent roof over the open porch outside Hagemeyer's studio. Here Weston obtained a beautiful high, strong light and made the portraits that earned him his living. Charis Wilson, who later became Weston's wife, remembered that the light there pleased him, and he photographed such local notables as Robinson Jeffers and Lincoln Steffens.[45] The cheesecloth over the porch was equally good for still lifes. Every

time Weston waited for a sitter to arrive, he turned to setups. Most of the images from 1930 to 1932 that Weston included in the Group f.64 show were made on this porch.[46]

Weston's controversial 1931 set-up image, Rock and Shell Arrangement , appeared to alter the scale of reality, for the shell filled the mouth of an enormous mountainscape. Weston insisted on including the photograph in Merle Armitage's book The Art of Edward Weston and in the de Young's Group f.64 exhibition. It provoked furious letters, which Weston ignored, from those who expected pictures to be "true to nature." Westons friend Ramiel McGehee said to him: "It is a stunt and if the book was mine, I would neatly with a safety razor blade remove the print from the book. It's the first time I've known you to make nature talk a language not her own."[47] Weston denied the "stunt": "I don't have to please the public" (a brave statement but hardly consistent with his pleasure in good reviews). Weston explained the motive for publishing the picture: "It deeply moved an intelligent audience as I was moved when I first saw its presentation on my ground glass." This image is a still life set out-of-doors. In using the word "arrangement," Weston signaled to the viewer what the picture was: his own placement of elements. He noted, "I did not add that word as an apology, rather to forestall criticism from naturalists that thought I was 'nature-faking.' "[48]

As the decade continued, the problems of the depression became more widespread, affecting artists and photographers already accustomed to existing on meager commissions and few sales. In San Francisco, and even in Carmel, critics questioned the premise of art. They accused the members of Group f.64 of failing to consider economic or social problems in their photography, which continued to center on things seen for their beauty. As Weston noted in February 1932, he knew that he was on uncertain ground, and that there were "right thinkers" who would have preferred that art function as a missionary to improve sanitary conditions; in 1933 he added, "I am 'old fashioned' enough to believe that beauty—whether in art or nature, exists as an end in itself. . .. If the Indian decorating a jar adds nothing to its utility, I cannot see why nature must be considered strictly utilitarian when she bedecks herself in gorgeous color, assumes magnificent forms."[49]

The matter may have seemed clear to Weston, but Van Dyke and others found compelling the argument that photography could describe social concerns. Van Dyke wrote a long and appreciatively perceptive article on Dorothea Lange, whose work he included in a show at 683. He accompanied Paul Taylor and other photographers on a significant visit to the self-help cooperative United Exchange Association (UXA) in Oroville, California. A trained agricultural economist, Taylor was an effective advocate for liberal economic views and the necessity for new jobs. Drawn to the photographers involved in 683, particularly Dorothea Lange, whose innate sympathy and direct vision in photography matched his own, he provided the clear example of what photography could accomplish if it were made to function politically, as it did when Lange's photographs led to the funding of a migrant workers' camp.

Despite their differences of opinion on photography as a political tool, Adams and

the others kept in close contact with Lange and Taylor. Later Adams developed many of Lange's Farm Security Administration negatives for her in his Yosemite studio, both Lange and Adams disagreeing with the FSA policy of insisting that photographers send their film to Washington for processing.

Weston's and Adams's strongly held belief in art for art's sake was often condemned, however. Weston wrote in his daybook that his kind of photographing could be compared to the work of a "Bohemian dabbler . . . frittering away on daubs and baubles to decorate the homes of our great democracy, using art as an excuse to loaf, to be supported like poodles, and petted by sexually unemployed dowagers—art patrons!"[50] Willard Van Dyke, socially aware and impressionable, had changed his outlook. He and Paul Taylor applied for a Guggenheim grant for a film on the UXA but were turned down. Ironically, in 1937 Weston received the first such grant awarded to a photographer—to photograph landscape.

The Legacy of Group f.64

Many factors, including the departure of several members from the Pacific Coast and Carmel, caused Group f.64 to break apart.[51] Weston went to Santa Barbara to be with his son; Willard Van Dyke (Fig. 100) left for New York and a career making movies (beginning with The River ). Although Mary Jeannette Edwards stayed at 683 Brockhurst, it is clear that she felt deserted. Returning some prints to Weston, she remarked in a letter, "I think the only course open to the group is not to show as f.64, but as a group of Western Photographers. There is such diversity in work and point of view."[52] In August 1935 she added, "Now I realize that my little 683 must be given up, as soon as I am economically able to make the move."[53]

Did the photographers who continued to be active evolve new ways of seeing and composing their photographs? Or did their increasing fame rest on the growing understanding of the general and museum-going public that photography, the pervasive language of the times, was uniquely significant? Ansel Adams evolved as a photographer, building on his extraordinary vision and technique, his passionate feeling for California land, and his ability to enlarge the meaning of landscape photography as central to environmental concerns. Weston applied his straight photography to a broader landscape on his Guggenheim trip and, in a darker view, to the final pictures of Point Lobos, but illness overcame him before major change could develop and be resolved in his work. The photographs he showed at the f.64 exhibitions constituted, as he thought, many of his most successful pictures.

Group f.64 provided a rallying place for like-minded photographers to gather, state their aims, and exhibit their carefully composed black-and-white images (Fig. 101) in defiance of the then reigning pictorialist tradition. That the proponents were young, bold, and optimistic about their chosen medium was important to the group's success. As an informal Oakland meeting place and gallery, 683 Brockhurst encouraged the

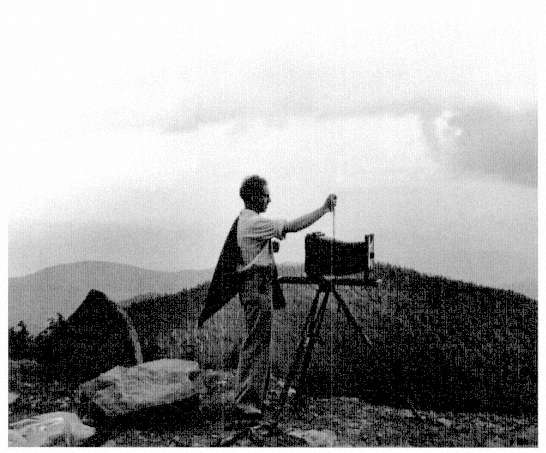

Figure 100

Peter Stackpole, Willard Van Dyke with View Camera , 1930s.

The Oakland Museum, gift of Douglas Elliott. Photograph courtesy Peter Stackpole.

revolutionary Bay Area modernist aesthetics that resulted in straight seeing and "pure photography."

Individually, four f.64 members combined their shared vision, adapting straight, clearly seen images for diverse purposes, from picturing California's stark beauty to addressing social issues. More remarkable, from this group of eight, four of the best-known and most celebrated photographers of the period emerged—Edward Weston, Willard Van Dyke, Imogen Cunningham, and Ansel Adams. One can postulate that although each of them was committed to making photographs, their collaborative effort, their entwined relationships, and their spirit of rebellion clearly benefited the

Figure 101

Sonya Noskowiak, Cypress, Point Lobos, Carmel, California , 1938.

The Oakland Museum, Photography Fund purchase.

younger members. The f.64 photographers gave an intriguing name and a specific location to a modernist movement that for the next forty years characterized American fine art photography. Cunningham captured the irony of their love of photography with humor and a determination to undermine pompous aims when she observed, "You have to be really crazy to stay in it, the way a photographer is treated . . . .You really have to be a mad person to stick to it. We did all seem to stick."[54]

Despite the pervasive and elegant modernism of a photography grounded in seeing straight and in a purist's modernist idiom, younger photographers changed, experimenting by revisiting mixed media and by striving for pictorial effects in their work. Perhaps manipulation, hand-coloring, and collage—all despised by the modernists of the 1930s—came to be acceptable once more as natural to artistic expression. Modernism in California first narrowed its focus to the purely photographic and then, by the 1950s, broadened it once more to encompass the wide range of media and images that could be imposed on paper.