War

Corinth's increasing pessimism, originally induced by his illness, was further nurtured by the cataclysmic events of the First World War, which he witnessed, though from a distance, with profound anxiety. His initial response to the outbreak of the war was, like that of many Germans, one of patriotic fervor. "Each German considers himself the special protector of the German hearth," he wrote at the outbreak of the war, evoking the memory of Bismarck, Blücher, and Luther. "The German Empire was resurrected anew through blood and iron in 1871, and the one who created Germany is one of the greatest men of our dear fatherland."[33] He spoke of the "courage" with which the "frivolous games" of the enemy were being warded off and of the "furor teutonicus" that would soon demonstrate to the world that peace in Germany was not to be disturbed with impunity.[34] He was deeply distressed by the Russian invasion of East Prussia in late August 1914 and by the subsequent devastation of many villages and towns, including Tapiau, where his painting Entombment (see Fig. 95) was destroyed in an attack on the city hall. It was in this general context that he referred to the war as a "Holy War."[35] Thomas Mann, incidentally, expressed his own patriotic sentiments in similar terms when early in the war he summoned his fellow Germans to recall the courageous example of Frederick the Great. Drawing a parallel between the coalition formed against Prussia in 1756, after Frederick had invaded Saxony in the name of self-defense, and the coalition formed against Germany in 1914, after the Germans had moved into Belgium with the same excuse, Mann wrote: "Today, Germany is Frederick the Great; . . . his soul . . . has reawakened in us."[36]

Corinth's most extensive pictorial response to the war is found in his graphics. During the initial and most volatile phase of the conflict he turned repeatedly to prototypical themes of aggression and combat: warriors attacking defenseless women or protecting them; knights engaged in battle or preparing for war. The subjects of Florian Geyer (see Plate 16, Fig. 127) and The Victor (see Fig. 105) also reappeared in 1914 (Schw. 171, 173), as did characters from other earlier paintings, although in a more generalized form to suit the new context. From The Fight between Penelope's Suitors and Odysseus (B.-C. 571), for example, one of the temperas for the Villa Katzenellenbogen, Corinth selected several figures, divesting them of their original identity to achieve a more universal meaning (Fig. 146). Other themes include the prototypical warrior Saint George (Schw. 187) and Joan of Arc (Fig. 147). The latter, too, was updated to reflect the new war. Although the heroine retains her medieval

Figure 146

Lovis Corinth, Warriors (Odysseus and the

Suitors ), 1914. Etching, 25.7 × 18.5 cm, Schw.

172. Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich.

Figure 147

Lovis Corinth, Joan of Arc , 1914.

Etching and drypoint, 24.4 × 19.4 cm,

Schw. 188. Orlando Cedrino, Munich.

Figure 148

Lovis Corinth, "Barbarians": Immanuel Kant ,

1915. Lithograph, c. 28.5 × 20.0 cm, Schw.

L207. Kunsthalle Bremen (40/563).

armor, among the combatants are a German and a French soldier in modern uniform, and the year 1914 is prominently inscribed inside a glory of light at the top of the composition.

Corinth repeated both the Joan of Arc and the Florian Geyer in 1915 (Schw. L201, L202) for one of the Krieg und Kunst series, portfolios of original lithographs published under the auspices of the Berlin Secession in support of the war effort. Other lithographs by Corinth from that year for Krieg und Kunst include Cain (Schw. L208) and portrayals of such German political and cultural heroes as Bismarck (Schw. L212) and Immanuel Kant (Fig. 148). The latter depicts the Königsberg philosopher looking down on his native city and includes in the title the word Barbarians in allusion to the recent invasion of East Prussia. Kant was not only dear to Corinth as a fellow East Prussian but also widely appreciated at the time for such "Germanic" qualities as his blond hair and steadfast, manly character. Like Johann Gottlieb Fichte, whose reputation was being cultivated anew by the Fichte Society founded at the outbreak of the war, Kant was seen as a fighter for the worldwide cultural mission of the German people.[37]

Figure 149

Lovis Corinth, Artist and Death II , 1916.

Etching, 18.0 × 12.4 cm, Schw. 239.

Kunsthalle Bremen (42/119).

The patriotic sentiment of Corinth's graphics was echoed many times over by other German artists, in Krieg und Kunst and in such wartime broadsheets as Kriegszeit and Künstlerflugblätter , both published by Paul Cassirer.[38] For Kriegszeit Ernst Barlach, for example, produced in 1914 the lithograph Holy War , based on his famous sculpture Avenger from the same year; other contributions by Barlach with such titles as First Victory Then Peace and Heavy Attack suggest the same pugnacious tone.

As the war progressed, Corinth grew increasingly distraught. The thought of death dominates two etchings from 1916 that show Corinth himself at work. In one of them (Fig. 149) he is virtually hemmed in by the human skeleton, familiar from the self-portrait in Munich (see Plate 9), and the skull of a ram attached to the back wall of the studio. In the second etching (Schw. 238) Corinth has turned away from his mirror image and sadly contemplates the macabre prop. Subjects from the Bible began to supplant the themes of aggression. Two Gethsemane scenes (Schw. 213, 214) date from 1915; in 1916 Corinth made the three prints of The Carrying of the Cross (Schw. L245, L246, 263; see Fig. 135), a Crucifixion (Schw. L285), and a set of six lithographs il-

Figure 150

Lovis Corinth, Beneath the Shield of Arms ,

1915. Oil and tempera on canvas, 200 × 120 cm,

B.-C. 656. Ostpreussisches Landesmuseum

Lüneburg.

lustrating episodes from the Apocalypse (Schw. L296). Here parallels can again be drawn between Corinth and the Expressionists. In 1916 Barlach transformed the idealized avenger of Holy War into a grotesque killer in a drawing and subsequent lithograph entitled Episode from a Modern Dance of Death . Rohlfs, Hofer, and Lehmbruck evoked the collective misery of the war in numerous paradigmatic portrayals of anguish, while with more than a touch of self-identification both Beckmann and Kokoschka turned repeatedly during these years to the iconography of Christ's Passion.

Figure 151

Lovis Corinth, Old Man in Armor , 1915. Oil on canvas,

125 × 91 cm, B. C. 654. Bezirksmuseum Cottbus; on loan

to Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, National-Galerie (DDR).

Themes of war are less frequent in Corinth's paintings. In 1914 he painted a knight in armor attacking a naked woman (B.-C. 619), and in 1915 he responded to the news that German troops had once again freed East Prussia from Russian occupation by painting a knight as a woman's stalwart protector (Fig. 150), inscribing the canvas "In Memory of the Assault on Memel."[39] Two other works from 1915 commemorate German heroes—Death Mask of Frederick the Great (B.-C. 653) and Martin Luther (B.-C. 655)—and a third depicts an old man in armor (Fig. 151); the model's feeble posture and dim gaze contrast

Figure 152

Lovis Corinth, Cain , 1917. Oil on canvas, 140 × 115 cm,

B.-C. 708. Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf (M 1986-4).

Photo: Landesverband Rheinland/Landesbildstelle

Rheinland.

sharply with the rigid strength of the weapons, testimony to a brave spirit seeking to defy the infirmities of old age. Borussia (B.-C. 705), the picture of an Athena-like Mother Prussia protecting a group of children around her; Cain (Fig. 152), a horrid rendering of the archetypal theme of fratricide; and a painting of yet another aged warrior, the historical figure Götz von Berlichingen (Fig. 153), all date from 1917. The knight, though fully armed for battle, is engaged not in martial pursuits but in committing his memoirs to paper. He writes with his left hand while his iron right hand, fashioned after his real hand was shot away during a siege, weighs heavily on the table. This work and the painting of the old man in armor from 1915 were preceded by etchings (Schw. 163B, 288), and it is difficult not to interpret both as surrogate self-portraits acknowledging that Corinth, too, experienced the war only from a distance. In the painting of Götz von Berlichingen, as in the earlier Samson Blinded (see Plate 22), the setting is a modern interior. Indeed, the framed

Figure 153

Lovis Corinth, Götz von Berlichingen , 1917. Oil on canvas, 85 × 100 cm, B.-C. 725.

Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte der Stadt Dortmund (C 4790).

Figure 154

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait in a White Smock , 1918. Oil on canvas,

105 × 80 cm, B.-C. 734. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne.

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv.

works of art in the background evoke the ambience of Corinth's own studio, where he often sat during these years engaged, like Götz, in writing his autobiography.

The theme of aggression is embodied once again in Rape (B.-C. 726), a painting from 1918, while Young David (B.-C. 731) from the same year conjures up the hope for victory and deliverance. Corinth's inability to sustain this hope, however, is evident from his diary. "It is horrible and terribly sad," the entry for October 17, 1918, concludes, that "after the war there will be peace, but it will arrive like the peace of the grave."[40] On November 3, the day of the armistice, he wrote: "The world of Bismarck and the Hohenzollerns has ceased to be. . . . A world of enemies has finally conquered us."[41] Two days later he wrote a single line in his diary, Hector's prophecy of the fall of Troy: "The day will come when sacred Ilion will fall, Priam too, and the people of the brave king."[42] In Corinth's final war painting his armor lies discarded, like a useless prop, on the floor of his studio (B.-C. 727).

Germany's defeat in the war was a harsh blow for Corinth, the more so since as a native East Prussian he identified personally with the Prussian state. As late as November 1, 1918, he still expressed the hope that the kaiser, no matter what his shortcomings and blunders, would not be forced to abdicate, that he would be supported, if need be, by the military.[43] Even after the out-break of the revolution Corinth declared proudly: "I consider myself a Prussian and a German of the Empire."[44]

Despite Corinth's trials during these years, his reputation continued to grow. The year 1917 in particular brought him much professional satisfaction. Major exhibitions of his works were held at the Kunsthalle in Mannheim and at the Kestner-Museum in Hannover; the Delphin Verlag published Herbert Eulenberg's biographical essay; and Fritz Gurlitt brought out Karl Schwarz's catalogue of Corinth's graphics. To cap it all, the Prussian Ministry of Culture bestowed on Corinth the title Professor, and the city magistrates of Tapiau made him an honorary citizen. The second edition of Corinth's autobiographical account Legenden aus dem Künstlerleben was published in 1918; in early March of that year the Berlin Secession opened a large retrospective in celebration of his sixtieth birthday.

Corinth himself marked the occasion with a self-portrait (Fig. 154). The colorism of this painting is unusually subdued: tones of white and gray predominate, enlivened sparsely with touches of green, yellow, and rose. The pictorial structure, as in Poussin's famous self-portrait in the Louvre, is determined by the framed canvases in the background. The bold brushstrokes,

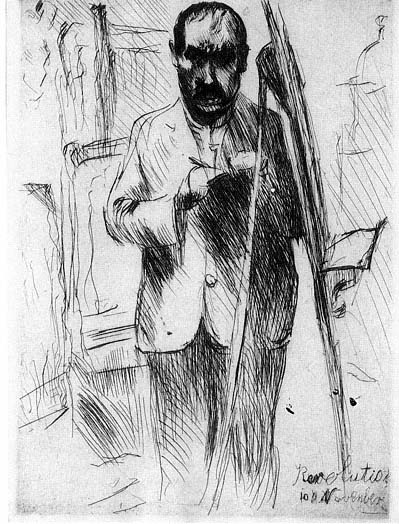

Figure 155

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait at the Easel , 1918. Etching, 25 × 18 cm,

Schw. 337. Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz,

Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin (West) (192-1931).

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

however, defy the strict logic of the composition, as does the painter's expressive gaze. Once again Corinth depicted himself in the act of painting. Prominently inscribed with roman numerals designating his age, the picture testifies to his undiminished commitment to his work. Several years later, reminiscing about the events of 1918, he did indeed write in his diary: "I had hoped to contribute to the recovery of Germany by creating works as good as I could possibly make them."[45] That his studio had become a place of refuge in a chaotic world is also suggested by the self-portrait etching inscribed "Revolution/10. November 1918" (Fig. 155). Whereas images of death had set an apprehensive tone for the two self-portrait etchings from 1916, here Corinth, surrounded by the implements of his profession, records his likeness with quiet resolution, a pillar of calm in a world gone berserk.

The real celebration of Corinth's sixtieth birthday, on July 21, took place in the secluded hamlet of Urfeld, at the shores of the Walchensee, in Upper Bavaria, where the painter and his family had taken lodgings at the Hotel Fischer am See. Although he was deeply moved by the beauty of the Walchensee, Germany's largest and deepest Alpine lake, he did not yet realize that this encounter with Urfeld and its environs would open a whole new chapter in his life.