3—

Maximizing Internal Benefits

"There are 10 million people up there," the Southampton homeowner warned, pointing to New York City 85 miles to the west, "and make no mistake about it, they're on their way here."[1] As in many suburbs in the New York region during the 1960s and 1970s, the cause for concern in affluent Southampton was a proposed garden apartment project. And like communities throughout the region faced with growing demands for more intensive land use, Southampton responded negatively, in this case with an amendment to the zoning ordinance which made the cost of garden-apartment development prohibitive.

Growth has been the basic influence on the politics of development beyond the inner ring of the New York region. Few communities can insulate themselves from the pressures for new homes, shopping centers, offices and factories, and from the changes that follow in the wake of these developments. With growth comes mushrooming demands on the newer suburbs for schools, roads, and sewers. In older suburbs, growth and change frequently produce increased residential densities, an influx of lower-income families and ethnic minorities, and commercial decline. Nor can any suburb escape the general rise in demand for increasingly expensive public goods and services. And all must grapple with the crucial questions of who will settle where under what kinds of restrictions, questions whose answers shape the political economy of each of the region's 775 suburban jurisdictions.[2]

From the regional perspective of many planners and urban specialists, development in suburbia represents a massive lost opportunity. As a consequence of local control of land use, hundreds of small-scale governments employ zoning codes and other regulatory devices to pursue parochial development goals. In the view of the critics, the uncoordinated and often contradictory development strategies that emerge from the suburban mosaic ignore sound planning principles and broad regional needs. The result, in the eyes of the Regional Plan Association, environmentalists, and like-minded groups and individuals, is a recurring pattern of inefficient development and disor-

[1] Quoted in Francis X. Clines, "Housing Curbed in Southampton," New York Times, March 6, 1966.

[2] The term "suburbs" as used in this volume refers to the municipalities of the New York region, minus the large older cities (New York City, Elizabeth, Jersey City, Newark, Passaic, Paterson, and Trenton in New Jersey, White Plains and Yonkers in New York, and Bridgeport, New Haven, Stamford, and Waterbury in Connecticut). Under this definition, a number of smaller cities such as New Brunswick, N.J. and Mt. Vernon, N.Y. are considered suburbs in the discussion in Chapter Three and Chapter Four.

derly growth, characterized by monotonous housing tracts, highly limited residential options for the lower and middle classes, vanishing open spaces, misplaced industry, overcrowded schools, congested highways, polluted air and water, overburdened utility systems, and spiraling taxes. In the absence of fundamental change in the system of land-use control and perhaps broader governmental reorganization as well, regional planners foresee more of the same in the spreading metropolis, as well as even greater inequalities in the distribution of costs and benefits among the residents of the tristate area.[3]

Most suburbanites perceive development politics in a different light. At the grass roots, development issues tend to be viewed in a narrow frame of reference focused largely on home, family, and local taxes. The typical suburban homeowner sees little need for change in local political institutions, since small-scale government usually provides a political system relatively responsive to homeowner interest in maintaining property values, preserving the residential character of the community, stabilizing local taxes, and providing adequate public education. This broad base of shared values among homeowners does not, however, always produce consensus on development issues. Thus, some in a residential suburb will favor new commercial or industrial development as a means of stabilizing local property taxes, while others will oppose such development as undermining the community's residential character. Moreover, not everyone in suburbia shares the values of the homeowning majority. Apartment dwellers are less sensitive than homeowners to the impact of locally financed public services on property taxes. Large-scale landowners and developers are primarily interested in maximizing the return on their investments. Managers of commercial and industrial establishments are more concerned with providing adequate access to their facilities and with the availability of labor and customers than with maintaining the residential character of a particular suburb. And a growing number of less fortunate residents of suburbia enter the political arena to seek low-income housing, access to jobs, and public schools more responsive to their needs.

Despite these crosscurrents, the development policies of the vast majority of suburban governments in the New York region have reflected the overriding interest of most of their constituents in protecting an investment in a home and its environs. As a result, most suburbs seek to control changes within their boundaries in order to maximize the benefits and minimize the costs of any new development to existing residents. They also try to minimize adverse effects within their jurisdiction of the activities of other public agencies, such as the state highway departments and planning agencies.

This chapter and the next analyze the efforts of suburban governments as they pursue these often elusive goals. Maximizing internal benefits is the primary concern of this chapter, while Chapter Four explores the suburbs' efforts to minimize the intervention of outside agencies. Before turning to this analysis, we examine briefly the capabilities which suburban governments in the New York region bring to the task of concentrating resources effectively to influence urban development.

[3] See, for example, Regional Plan Association, Spread City, RPA Bulletin No. 100 (New York: 1962); and Tri-State Regional Planning Commission, Proceedings: Tri-State Regional Conference (New York: 1976).

Suburban Capabilities

Almost all of the region's suburbs bring similar advantages to the complex task of shaping development along desired lines. These developmental assets are formal independence, control over the use of land, and a relative lack of conflicting constituency demands. Each faces the same basic set of constraints: limited areal scope, limited political skills, reliance on the property tax, and at least formal dependence upon the state government. Moreover, location, topography, socioeconomic composition, and the pattern of previous development strongly influence the ability of any particular unit to overcome its inherent shortcomings and to concentrate its resources effectively. As the discussion in this and the next chapter indicates, great variations exist in the ability of suburban jurisdictions to shape development. Equally important, given the nature of suburban capabilities, some kinds of development decisions are far more susceptible to suburban influence than others.

The Constraint of Size

Most suburbs in the New York region are small. More than half of the 775 suburban jurisdictions encompass less than five square miles. In 1970, the average suburb had approximately 14,000 residents. But almost 10 percent of the suburban units had fewer than 1,000 inhabitants. And only eight had 100,000 or more residents, all of which were two-level local jurisdictions in Nassau and Suffolk counties.[4] (See Table 11.)

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The limited areal scope and small population of the typical suburb shapes to a considerable degree its role in the politics of urban development. Small size means limited financial resources and, perhaps more important, limited political skills. Because of the resource constraints imposed by size and reliance on the property tax and state assistance, most suburbs are rarely able to use their construction and other investment decisions to influence development. Instead, they rely primarily on zoning and other regulatory devices in their efforts to shape development along desired lines. Limited financial resources also combine with restricted area to increase the reliance of suburban jurisdictions on special agencies to provide water, sewage dis-

[4] The suburban jurisdictions with populations over 100,000 in 1970 were the towns of Hempstead, North Hempstead, and Oyster Bay in Nassau County and the towns of Babylon, Brookhaven, Huntington, Islip, and Smithtown in Suffolk County. All of these large towns encompassed villages, as discussed below and indicated in Table 12.

Bergen County's 78 MunicipAlities Map 3

posal, and other public services that are beyond the fiscal and territorial capacity of the individual municipality. As for political skill, few suburbs are large enough to support full-time elected officials, specialized bureaucracies, or professional planning agencies; and many are so small as to have no effective administrative capacities at all. Nor is the average suburb large enough by itself to have much influence in the political arenas of the region, state, and nation. To some degree, however, these political weaknesses are offset by

common interests among suburbs on many development issues, the responsiveness of state legislatures to widely shared suburban interests, and the availability of financial and technical assistance from the states and the federal government. A good example of the latter is the federal 701 program, which has provided funds to many suburbs for professional planning assistance they could not otherwise afford.

Limited areal scope also greatly restricts a suburb's sphere of action. For the typical suburban unit, the small amount of territory under local control makes it highly vulnerable. The decision of one of New York City's neighbors to change the character of territory adjacent to the city may adversely affect the fortunes of one or two neighborhoods, but it will not disrupt the city as a whole. Similarly, construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway cut a wide swath through a section of New York City, but had little impact on the overall pattern of development in the city. This is not the case with small suburban jurisdictions. A six-lane expressway may take a sizable proportion of the taxable property in a three-square-mile municipality, as well as permanently bifurcate a residential community. The efforts of a small suburb to exclude garden apartments or industry may be undermined by a neighboring community's decision to accept such development in order to increase the amount of taxable property (or tax ratables). Because the suburb in question is small, the actions of adjacent municipalities can have as much effect on the character of the community as its own land-use controls.

Illustrative of suburban vulnerability is the impact of large shopping centers on surrounding areas. One of the attractions for local officials in Wayne Township of the massive Willowbrook shopping center located on Wayne's border has been that neighboring Little Falls gets "all the traffic and harassment. We get all the taxes."[5] Given this kind of mismatch between costs and benefits, residents of adjacent communities typically oppose such developments. Plans for the construction of a large shopping center in Yonkers adjacent to its boundary with Hastings-on-Hudson were vigorously denounced in Hastings. "We would not benefit from the shopping center but it would cost us a lot," argued the opponents. "Tax revenues would all go to Yonkers while our shops would be wiped out. We would need more police and wider roads. Our property values would drop too."[6] Increasing the vulnerability of suburbs such as Hastings-on-Hudson is their lack of any direct role in the decisionmaking processes of neighboring communities.

Variations Among Suburbs

One of the most striking features of the New York region—another product of its size and scope—is the great variation among the 775 units of general government in suburbia. In addition to differences in size that affect suburban development capabilities, important variations in the structure and function of local government result from the tristate nature of the New York region. The most complex local governmental arrangements are found in New York

[5] Harry Butler, former mayor of Wayne, N.J., quoted in Jack Rosenthal, "Suburbs Abandoning Dependence on City," New York Times, August 16, 1971.

[6] Mrs. Richard Evans, Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y., quoted in James Feron, "Huge Shopping-Mall Plan Stirs a Battle in Yonkers," New York Times, June 18, 1973.

State where, as Robert C. Wood points out, "no hard and fast rules exist with respect to the division of functions among . . . governments."[7] In suburban New York, the primary units of local government—cities, towns, and villages—have varying degrees of independence, although all have power to control land use. Cities have more autonomy than towns, which depend on county government for a number of important functions. Villages are subdivisions of towns, empowered to control land use and other local functions within their boundaries. Towns are particularly important on Long Island since large portions of Nassau and Suffolk counties have not been subdivided into villages. As indicated in Table 12, only 23 percent of the population of the eight largest towns on Long Island lived in villages in 1970.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Further complicating the picture in New York is the widespread use of local special districts in suburban counties. (See Table 13.) In addition to six cities, eighteen towns, and twenty-two villages, Westchester had ninety special districts in 1977 empowered to raise local taxes to finance education, fire protection, garbage collection, street lighting, water supply, and other public services. Another important feature of the New York system for the politics of development is the subdivision of the towns for the provision of public education. In Suffolk, for example, the county's ten towns contain seventy-five school districts, each with its own local tax base. This means there are substantial tax differentials among school districts within a town, as well as competition within a town for development that will contribute to the financing of public education.

| ||||||||||||||||||||

[7] Robert C. Wood, 1400 Governments (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961), p. 24.

County government plays a more significant role in New York than in New Jersey (or in Connecticut, where county governments were abolished in 1960). The three large New York suburban counties—Westchester, Nassau, and Suffolk—have developed strong county-government units. Each has a full-time elected political executive, a substantial budget, an active and professional planning agency, and major responsibilities that affect development policies, including highways, water supply, sewage disposal, and recreation. A counterweight to these centralizing forces was provided prior to 1970 by the direct representation of towns (and cities in the core of Westchester) in the county legislature, which tended to make the New York counties particularly responsive to the interests of their component local governments.[8]

In New Jersey, all general purpose local units—cities, boroughs, villages, towns, and townships—have been delegated approximately the same functions by the state legislature. These primary units of local government share few powers with county governments, which have considerably less responsibility than in New York. Also in contrast with New York, school-district boundaries in New Jersey generally coincide with those of municipalities. And local special districts are relied on less than in the New York suburbs. In the Connecticut corner of the region, cities and towns function in the absence of county government, and independent school districts are less numerous than elsewhere in the region, but special districts for other functions are extensively used.

As indicated in Chapters One and Two, suburbs in the New York region also vary in terms of their pattern and time of settlement, state of development, socioeconomic composition, and property tax revenues per capita. All these factors influence an individual suburb's development goals and capabilities. Most of Bergen County's seventy municipalities are residential communities whose development interests and resources differ from those of "atypical" Bergen municipalities like Teterboro, a completely industrial borough, or Hackensack, the county seat and an older commercial center, or Paramus, a booming industrial, commercial, and residential community at the juncture of several major highways. But just as significant for the politics of development are the differences among Bergen's many bedroom communities. Lower-middle-class Waldwick, slowly recovering from the trauma of rapid expansion in the automobile age, inevitably views development strategies such as the attraction of industry more favorably than neighboring Ridgewood, a stable upper-middle-class municipality settled more than a generation ago by rail commuters whose principal development goal was the maintenance of a comfortable status quo. A different set of development problems preoccupy Englewood—an older suburb of large homes a few miles to the east of Waldwick and Ridgewood—because Englewood includes an increasingly militant low-income black neighborhood. And along the urban frontier, in northwest Bergen's Oakland, the politics of development are framed in terms

[8] The county legislatures, which were known as boards of supervisors, were reorganized after a court suit overturning the apportionment of seats on the basis of local governmental units rather than population. Suffolk and Westchester replaced their boards with county legislatures based on single-member districts, thus eliminating the direct representation of local governments and their officials. Nassau retained direct representation of local units by providing each of its town supervisors with a vote on the board of supervisors weighted according to population.

of larger-lot zoning designed to insulate the town's affluent suburbanites from the adverse consequences of urban growth and change.

Homogeneity and Heterogeneity

The differences among communities like Waldwick, Ridgewood, Oakland, Englewood, Paramus, Hackensack, and Teterboro make Bergen County as a whole—or for that matter, almost any other suburban county in the New York region—a varied aggregation of people and jobs. During the past quartercentury, the overall heterogeneity of suburbia has been enhanced, as large numbers of blue-collar workers and an increasing number of low-income families have followed the middle class into the suburbs. Because of the aging process in the inner suburbs, the growth of apartment living outside the cities, and the influx of blacks and Puerto Ricans into many areas, a growing number of municipalities in the suburbs have more in common with the older cities than with the newer suburban areas. Almost 62,000 of Nassau County's 1.4 million residents were below the poverty line in 1970; and one-third of the county's $270-million budget was devoted to welfare. Almost one-half of Westchester's population lives in four older suburban cities—Yonkers, Mount Vernon, New Rochelle, and White Plains. Thus, from the regional perspective, suburbia increasingly shares the socioeconomic diversity of the older cities, leading some observers to speak of "the City of New Jersey," and to comment that "Long Island Is Becoming Long City."[9]

But suburbia certainly is not a city in the political sense of being a single heterogeneous municipality. Upper-income families cluster in a few suburban jurisdictions, middle-income families predominate in a large number of suburbs, others are populated mainly by blue-collar suburbanites, and blacks and other low-income groups are concentrated in the municipalities which contain suburbia's older and less desirable housing. Thus it is not surprising that most suburbanites do not perceive their communities as becoming more city-like. In a 1978 survey, 63 percent of the suburban dwellers responded negatively to a question which asked whether their area was becoming more like a big city.[10]

In general, the socioeconomic variations among suburbs tend to be substantially greater than the variations within any one community. The relative homogeneity of the individual suburb results from superimposing the typical urban pattern of neighborhood differences along income, ethnic, and racial lines on the small scale of the average suburban municipality. Reinforcing this tendency has been the uniform pricing of large-scale housing developments and local land-use policies, which tend to set similar housing patterns within a town, thus homogenizing income levels within any one community. Consequently, the growing heterogeneity of suburbia as a whole rarely is reproduced in individual suburbs.

The socioeconomic homogeneity of the typical suburb has important consequences for development politics in the New York region. Compared

[9] See Joe McCarthy, "Long Island Is Becoming Long City," New York Times Magazine (August 30, 1964), pp. 17, 65–67; and John E. Bebout and Ronald J. Grele, Where Cities Meet: The Urbanization of New Jersey (Princeton: Van Nostrand, 1964), pp. 91–111.

[10] New York Times, "1978 Suburban Poll" (1978), p. 8.

with the older cities, the residents of any one suburb exhibit greater consensus on development goals, and generate fewer conflicting pressures on local policymakers. Internal consensus on goals helps many suburbs overcome some of the constraints imposed by restricted areal scope, limited resources, and the internal fragmentation of formal governmental authority among general-purpose units, semiautonomous planning boards, school districts, and other special-purpose agencies. When, as is often the case, these agencies share the same constituency, and the constituency largely agrees on community goals, policy determinations in each agency tend to be consistent and mutually reinforcing.

The importance of homogeneity in suburban politics also is illustrated by the fact that goal conflict is most common in the more extensive jurisdictions and the older suburbs, both of which typically encompass more varied populations. Finally, limited areal scope and homogeneity tend to structure many development issues along "external" rather than "internal" lines. More often than not, development contests involve conflict with outside parties—other municipalities, state highway agencies, garden-apartment developers, or blacks who desire to purchase homes—rather than conflict among groups and individuals within a particular suburb.

The Central Fact of Autonomy

All of the distinguishing features of the suburban political arena—fragmentation, small-scale government, variation among suburbs, and homogeneity within them—are rooted in the considerable autonomy delegated to the primary units of local government by the states of Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. Independence is the most significant political resource of most suburbs in the struggle to shape development along lines desired by residents, to maintain freedom of action in the competition for revenue sources and desirable development, and to avoid situations in which the costs to a community outweigh the benefits. Through incorporation and other forms of state delegation, local communities in the region are protected from the territorial ambitions of other jurisdictions, are shielded from unattractive joint ventures, and are given varying degrees of control over local services, expenditures, taxes, and land use.

Suburban independence is, of course, limited rather than absolute. As is the case with the older cities, suburban municipalities are creatures of state government. Although the patterns vary from state to state, local autonomy is limited by the setting of state standards, the mandating of local expenditures by the state legislature, the assignment of responsibilities to counties and special districts, and the retention of activities by the state itself. The state agencies that build highways, colleges, parks, and other public facilities are not subject to local land-use controls. And the state courts are the principal arbiters of disputes that arise over the actions of state agencies within suburbia and over the use by local governments of state-delegated powers.

Local control, however, is practically complete with respect to the regulation of land use, the most significant aspect of suburban autonomy for the politics of development. Like all local powers, control over land use is derived from the state government. But state legislatures, responsive to suburban inter-

ests, have been reluctant to interfere with local prerogatives in this extremely sensitive area of public policy. With only a few exceptions, state agencies have no active policymaking role in land-use regulation. Moreover, the courts in the three states traditionally have been wary of substantive challenges to local land-use regulations, confining themselves instead until recently to procedural issues.[11] As a result, over the past quarter-century suburban regulatory bodies in the New York region have enjoyed great freedom in using zoning and building codes, subdivision regulations, and other devices to control lot size, the area and height of structures, and the location and use of buildings for specific purposes. Through their ability to regulate land use, suburban governments strongly influence population densities, settlement patterns, the location of commerce and industry, tax rates, and the overall quality of life.

Local regulation of land is hardly an accidental consequence of political independence. On the contrary, the desire for local autonomy in the development process has been a primary cause of the fragmentation of the New York region into independent small-scale jurisdictions during the past century. Between 1860 and 1930, 450 municipalities were created in New Jersey largely in response to the desire of land owners, real estate agents, and residents for local control over land use and public services. In 1894 alone, twenty-six local government units were organized in Bergen County, whose seventy municipalities in the words of a recent chairman of the county planning board "are mostly the handiwork of politicians, lawyers, and real estate agents who each had his own interest to look after."[12]

The benefits promised by community control continue to generate pressures for the creation of new primary units of local government, particularly in the unincorporated villages of New York's sprawling towns. For example, in 1963 demands for autonomy over local land use led tiny Hampton Bays (population 1,512) to consider breaking away from the town of Southampton in Suffolk County. A few years later, residents of Strathmore, a Levitt development, sought political independence as a way to escape the zoning and planning controls of Brookhaven, Suffolk's largest town. In Rockland County, the prospect of a $75 million garden apartment complex prompted homeowners to incorporate Pomona in 1967 to protect their neighborhood against development decisions by town governments they considered unresponsive to their interests.[13] During the same year, estate owners in Purchase attempted unsuccessfully to secure local land-use control through incorporation as a village, in order to prevent the development of a $12 million corporate headquarters in

[11] Of the three states, New Jersey's courts were most active during the 1970s in restricting local freedom of action in controlling land use, particularly when housing for lower-income families has been at issue. The most important ruling was handed down by the New Jersey Supreme Court in Southern Burlington County N.A.A.C.P. v. Township of Mount Laurel, 67 N.J. (1975). The Supreme Court concluded that "developing municipalities" like Mount Laurel—which is located outside the New York region in Burlington County, one of the most rapidly developing parts of the Philadelphia region—have an obligation to consider the housing needs of all categories of people in devising and applying local land-use regulations.

[12] Edward Erarich, quoted by Robert Houriet, "Many Motives Created State's Small Municipalities," Newark Sunday News, August 28, 1966.

[13] The area incorporated as Pomona was located in the towns of Hayerstraw and Ramapo. In 1970, Pomona's population was 1,792, while Haverstraw had 25,311 residents and Ramapo 76,702.

their unincorporated section of the sprawling town of Harrison. In 1979, voters in North Tarrytown and Pleasantville in Westchester County overwhelmingly approved referenda directing local officials to seek independence. In the case of North Tarrytown, local autonomy promised $220,000 in tax savings and $90,000 in additional federal and state aid, at the cost of only $43,000 in new expenditures.[14] The fact that almost all of these efforts failed indicates that the political geography of the region is far less malleable than in the past, largely because existing suburban jurisdictions are increasingly unwilling to lose control over areas whose development promises tax or other advantages to the community as a whole.

The Pervasive Influence of the Property Tax

Local dependence on the real property tax also plays a crucial role in the suburban quest for political autonomy and community control over land use. More than 60 percent of all suburban revenues in the New York region are derived from local property taxes, state assistance providing the only other major revenue source for most municipalities. Since property tax revenues are a function of the way land is used, as are the public expenditures necessitated by development, the power to regulate land use is the key to fiscal planning in most suburban jurisdictions. Commercial and industrial development normally generates more property tax revenues than local expenditures, and thus is considered profitable by most suburbs. Some kinds of housing—expensive single-family dwellings on large lots and apartments that are too small to accommodate families with school-age children—also generally produce local "profits." On the other hand, apartments with two or more bedrooms, most single-family housing developments, mobile homes, and subsidized housing projects almost invariably involve local expenditures that are substantially greater than the local taxes paid by these forms of housing.

As the New York region developed, suburban communities sought with considerable success to stake out local boundaries that would maximize property-tax revenues and minimize high-expenditure development. Discussing the creation of sixty-four new municipalities in New Jersey during the 1920s, John E. Bebout and Ronald J. Grele observe: "Tax avoidance was a main reason for setting up new municipalities . . . both newcomers and old settlers tried to escape social responsibility and higher taxes."[15] Similar objectives motivated the more recent efforts to incorporate villages in New York, already noted. The wealthy residents of Purchase in Westchester hoped to lower their property taxes by fencing themselves off from more intensely developed sections of Harrison. In Suffolk, the advocates of Strathmore's incorporation sought residential tax relief by folding most of the area's industrial development into their proposed municipality.

The significance of political autonomy and fiscal zoning grows as the spiraling costs of suburban government produce steady increases in property taxes. Especially important is the fact that educational costs, the principal component of suburban expenditures, have been rising much faster than other

[14] See Ronald Smothers, "'Breakaway' Villages Worry Albany," New York Times, May 13, 1979.

[15] Bebout and Grele, Where Cities Meet: The Urbanization of New Jersey, pp. 61–62.

outlays. Restrictions on development designed to limit the size of the schoolage population are the most effective means of controlling education costs. Although school-district budgets are frequently rejected by the public in referenda, particularly in the rapidly developing suburbs, these expressions of voter discontent rarely produce significant cuts in educational expenditures, and have little effect on the upward climb of school taxes. While state assistance underwrites a growing proportion of local school costs, state aid to date has not been sufficient to reduce significantly suburban efforts to employ land-use regulation as a means of limiting families with school-age children.

Political fragmentation, the property tax base, fiscal zoning, and rising educational costs combine with neighborhood differentiation and the locational decisions of commerce and industry to produce a significant mismatch of resources and needs in the region's suburbs. Consider the impact of land-use regulation and settlement patterns on two of Harrison's four school districts. The district encompassing Purchase, largely composed of estates and four-acre minimum lots, had $99,000 in property for each of 204 pupils in 1967, while the district embracing the more intensively settled section of Harrison backed each of its 2,450 students with only $19,000 worth of real estate. Moreover, the municipal beneficiary of a major commercial or industrial facility rarely has to bear anything approaching the full costs of educating the employees' children or providing other public services. For example, one of IBM's Westchester plants happens to be located in the Ossining school district, while most of the school costs generated by the IBM development fall upon the neighboring Yorktown school district. A beleaguered local school official complains: "The wealthier get wealthier and we get the additional children to educate. Now people perhaps will understand why I want the four districts to merge."[16]

Of course mergers, zoning changes, and other schemes designed to bring suburban resources into line with needs are strenuously resisted by jurisdictions that benefit from the existing system. A typical example of the response of the "haves" to the needs of the "have-nots" is provided on Long Island's North Shore, where the New York State Department of Education pressed for a merger of a number of school districts with varying tax bases into a single district. The ironic response was a merger of the two wealthiest districts, Stony Brook and Setauket, in order to foreclose consolidation with the poorer districts.

The Logic of Exclusion

Throughout the region, the developmental and fiscal pressures generated by the outward movement of people and jobs have produced increasingly restrictive zoning ordinances and building codes, outright bans on multiple-family housing or severe limitations on the size of apartment units, prohibitions on cluster developments and mobile homes, and highly selective strategies to attract industrial and commercial taxable property. The primary goal of

[16] Louis Klein, Superintendent of Schools, Harrison, N.Y., quoted in Merrill Folsom, "Westchester Finds Influx of Business a Worry," New York Times, August 18, 1967.

these suburban strategies is to maintain or achieve favorable ratios of property-tax revenues to demands for public services, while preserving or upgrading the residential amenities.

In a suburban political economy where local taxes are highly sensitive to land-use decisions, and where constituency concerns tend to be localistic and conservative, efforts to maximize the internal benefits of development constitute a rational course of action for the local policymaker. As Paul Davidoff points out, "they act perfectly rationally to protect their interests by keeping everybody else out. And you can see their success by looking at the number of development projects turned down by any suburban government. They only change zoning if they desperately need industry to help pay the tax bills."[17] Of course, what is rational for a local community may be highly disadvantageous for individuals whose housing opportunities are limited by the actions of suburban governments, or for developers whose prospects for profits are diminished, or for those who seek a more regionally oriented "rational" pattern of development.

Nor is a rational local strategy necessarily effective, even for the individual community. The patterns of past development and topography play a role in determining the relevance and effectiveness of particular strategies for maximizing internal benefits, as do political and technical skills used in devising and implementing policies suited to the particular circumstances. The influence of local land owners, developers, and corrupt officials can undermine local plans and zoning ordinances. But perhaps the most important factor of all is foresight. As Wood emphasizes, "the real effectiveness of land-use policies hinges on their timing: the date when comprehensive programs are applied."[18]

The Westchester Approach

Certainly foresight accounts for much of Westchester County's success in developing and applying public policies designed to maximize internal benefits and minimize the impact of the forces of regional growth and change. In 1912, the Bronx Parkway Commissioners forecast that "Westchester would rapidly become no more than an extension of the Bronx."[19] But Westchester's leadership, as pointed out in Chapter One, was determined to prevent the "Bronxification" of their largely unsettled county. The basic strategy was devised under the guidance of county Republican leader William L. Ward, whose goal was to attract "class" rather than "mass" to Westchester. Instead of rapid transit or typical highways, the county built parkways that restricted

[17] Quoted in Richard Reeves, "Land Is Prize in Battle for Control of Suburbs," New York Times, August 17, 1971. Davidoff was one of the founders of the Suburban Action Institute, a public interest advocacy organization that has brought court actions against a number of exclusionary suburbs in the New York region, and has pressed the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission to play a more assertive role in expanding housing opportunities for lower-income and minority families in the region's suburbs. For Suburban Action's view of its mission, see Linda Davidoff, Paul Davidoff, and Neil N. Gold, "The Suburbs Have to Open Their Gates," New York Times Magazine, November 7, 1971, pp. 40–50, 55–60.

[18] Wood, 1400 Governments, p. 111.

[19] See Robert Daland, "A Political System in Suburbia" (typescript, 1960), pp. 111–115. The discussion in this and the following paragraph draw heavily on Daland's excellent case study.

commercial traffic and strip development while preserving a rural atmosphere. Land use was controlled by autonomous suburban jurisdictions that jealously guarded the integrity and residential image of individual communities far more than would have been possible if zoning had been in the hands of a large-scale countywide jurisdiction with a heterogeneous constituency. With the encouragement of a talented county planning agency and the assistance of professional consultants, Westchester's local governments developed and applied sophisticated regulatory techniques in advance of major development pressures, and long before most other suburbs in the region.

Because of the timely and skillful application of appropriate policies, along with a powerful assist from topography, what Robert Daland calls "the image of Westchester" has been substantially preserved. Outside of Yonkers, New Rochelle, Mount Vernon, and White Plains, contemporary Westchester is characterized by "rural appearance, low population density, a high standard of amenities for the good life, and an elite citizenry."[20] Low-density development has given many Westchester communities a favorable balance of property tax revenues over demands on the public exchequer. Consequently, high levels of service have been maintained without undue burdens on the local taxpayer. Under these conditions, indiscriminate pressures for industrial and commercial development to relieve local tax burdens have been rare. The most successful and affluent communities, like Scarsdale and Bronxville, want no industry or large-scale commerce at all. Elsewhere in the county, highly selective industrial and commercial strategies have been pursued in recent years with considerable success.

In no other suburban county in the New York region have so many municipalities successfully pursued the goal of maximizing internal benefits. At the other end of the scale in terms of overall success in moderating the forces of suburban growth is Nassau County, where primitive land-use controls in most municipalities were overrun by the postwar surge of development eastward. Nassau's governmental structure was much like that of Westchester, but its political leaders and their constituents showed little of the foresight and interest in controlling development found in Westchester. The early suburbanites in Westchester were more affluent than those in Nassau; most tended to define their interests in terms of the preservation of an attractive residential locale for themselves, and the county's political system reflected these interests. In Nassau, on the other hand, the pressures for mass development represented an opportunity for profits rather than a threat to a way of life for most potato farmers and other land owners. Moreover, even if Nassau had used sophisticated planning techniques in advance of development pressures, its topography would have reduced the prospects for success in comparison with Westchester. With much of its terrain fiat and treeless, Nassau inevitably was far more susceptible to mass development, and considerably less attractive to the affluent than hilly, wooded Westchester.

On the other hand, a few communities within Nassau, particularly those along the scenic North Shore of Long Island, have followed the Westchester

[20] Ibid., pp. 111–114. The diversity of Westchester's various communities and the implications of this diversity for contemporary housing are examined in John Levy, "The Politics of Housing in Westchester," New York Affairs 5(1979), pp. 95–102.

strategy with considerable success. Other municipalities that have emulated Westchester are scattered throughout the region, and their ranks are growing as development pressures encompass more and more communities. Within their boundaries, timely application of land-use controls has combined with other factors—topography, convenient access to the Manhattan central business district, or the pattern of past development—to produce upper-income sanctuaries effectively insulated from many of the pressures and costs of regional growth. For these communities, like Short Hills in Morris County and Princeton Township in Mercer County, the key to the good life is the use of governmental powers to ensure the maintenance of a "single-family residential area of high-quality amenity and visual attractiveness."[21]

Planning for Fewer People

In all suburban areas, the power to regulate land use is the primary means available to direct growth, protect the tax base and property values, and preserve amenity and community character. Throughout the New York region, more restrictive zoning and building codes have been the typical suburban response to population growth. A large developer explores possibilities for tract housing in Cranbury in southern Middlesex, and quickly is faced with the rezoning of most of the township's vacant land upward to one-acre parcels. In Millburn, in Essex County, the local government examines development trends and responds with two-acre and five-acre zoning in order to "make sure that the type of township we have now will be preserved in the future."[22] In addition to increases in minimum lot sizes, suburbs seek to limit intensive and inexpensive development by requiring minimum house sizes, forbidding mass-produced housing through such devices as "no look-alike" provisions in local zoning ordinances, enacting building codes that drive up the costs of housing construction, prohibiting the construction of multiple-family dwellings, restricting the number of bedrooms in apartment units, and forbidding mobile homes.[23]

The region's richer suburbs have the most restrictive codes and the most successful development policies, but almost every suburb with vacant land has sought to maximize internal benefits by zoning for fewer people. Over the past quarter-century local planning throughout the region has become far more sensitive to the costs and benefits of residential development, in part because state and especially federal planning assistance have provided resources for professional staff and consultants. Along the region's frontier, planners teach the contrasting lessons of Westchester and Nassau to those who still harbor the "misconception that the more houses you build, the more ratables you have, and the lower your tax burden."[24] Sophisticated plans are developed to limit population, with increasing attention given to environmen-

[21] Princeton Township Planning Board, 1967 Annual Report (Princeton, 1968), p. A-3.

[22] Mayor Ralph F. Batch, quoted in the Newark News, December 21, 1965.

[23] See Michael N. Danielson, The Politics of Exclusion (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976), especially pp. 50–74; Mary Brooks, Exclusionary Zoning (Chicago: American Society of Planning Officials, 1970); and Norman Williams, Jr., and Thomas Norman, "Exclusionary Land Use Controls: The Case of Northeastern New Jersey," Syracuse Law Review 22 (1971), pp. 475–507.

[24] Donald McCoy, planning board secretary, Hopewell Borough (Mercer County), quoted in Trenton Times, August 15, 1967.

tal factors that are seen as severely constraining future development. In intensively settled suburbs like Madison Township in Middlesex, new homeowners in their tract houses soon grasped the rudiments of suburban political economy. Faced with rapidly mounting costs caused by mass development on 50-by-100-foot lots with no offsetting industrial or commercial property, Madison residents sought relief by rezoning undeveloped land for one-half and one-acre lots, so that people like themselves would no longer be able to settle in the municipality.[25]

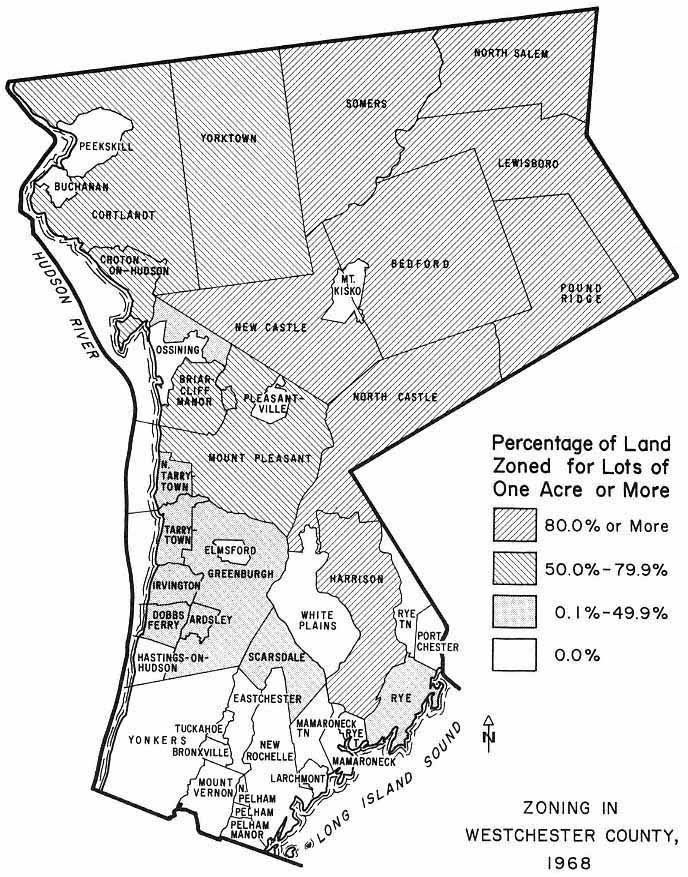

Largely as a result of these pressures in suburbs rich and poor, the average lot size in five inner- and intermediate-ring counties—Fairfield, Bergen, Middlesex, Passaic, and Westchester—more than doubled between 1950 and 1960. In 1952, Westchester was zoned for 3.2 million people; nineteen years later upzoning had reduced the county's residential capacity to 1.8 million. By 1962, two-thirds of all the vacant land in the New York region was zoned for one-half-acre or larger lots, while two-fifths of the total was reserved for parcels of one acre or more. Over half of all the land in Westchester's towns—which encompass most of the county's undeveloped acreage—was zoned for lots of two acres or more by 1968. (See Map 4.) By 1970, in the New Jersey suburban belt which encompasses Morris, Somerset, Middlesex, and Monmouth counties, over three-quarters of the undeveloped residential land was zoned for one acre or more, and houses of at least 1,200 square feet were required on 77 percent of the total acreage available for single-family dwellings.[26]

The trend toward more restrictive land-use controls in the New York region drew increasing fire in the late 1960s. Civil rights groups, fair housing organizations, labor unions, and other critics attacked the exclusion of blacks, lower-income groups, and blue-collar families from housing opportunities in the suburbs. Among the more vocal opponents of restrictive zoning are institutions with a regional perspective, such as the Regional Plan Association and the New York Times . The RPA's report on "Spread City" scores suburban land-use policies for promoting social irresponsibility, exporting costs and problems to others, wasting land, increasing the costs of public-utility systems, and undermining public transportation.[27] Similar concerns have been voiced by state officials in New Jersey, who have advocated a reversal of municipal land-use trends in the face of the state's growing housing crisis.[28]

[25] Madison Township's zoning restrictions were successfully challenged in state court in 1971 by a developer and Suburban Action Institute; see Oakwood at Madison, Inc. v. Township of Madison, 117 N.J. Super 11 (1971) and Oakwood at Madison, Inc. v. Township of Madison, 128 N.J. Super 438 (1974). During the course of the extended court fight, Madison Township changed its name to Old Bridge Township.

[26] See Regional Plan Association, Spread City, RPA Bulletin No. 100 (New York: 1962); Economic Consultants Organization, Zoning Ordinances and Administration (New York: 1970); Westchester County Department of Planning, Interim Report 6, Residential Analysis for Westchester County, New York (White Plains, N.Y.: 1970), pp. 8–15; and State of New Jersey, Department of Community Affairs, Division of State and Regional Planning, Land Use Regulation: The Residential Land Supply (Trenton: 1972), pp. 14–16.

[27] See Regional Plan Association, Spread City, passim .

[28] See State of New Jersey, Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Division of State and Regional Planning, The Residential Development of New Jersey: A Regional Approach (Trenton: 1964); State of New Jersey, Governor, A Blueprint for Housing in New Jersey, A Special Message to the Legislature by William T. Cahill, Governor of New Jersey (December 7, 1970); and State of New Jersey, Governor, First Annual Message to the Legislature, Brendan Byrne, Gover-nor of New Jersey (January 14, 1975). Efforts by the Cahill and Byrne administrations to ease suburban zoning restrictions are discussed in Chapter Five, as are earlier proposals made during the administration of Governor Richard J. Hughes.

Map 4

Zoning in Westchester county, 1968

Vigorous support for these proposals comes from most of the region's residential developers, who have little love for the land-use practices of the "tight little islands with a stay-out sign for home builders [and which] are unconcerned about the population explosion."[29]

[29] John B. O'Hara, President, New Jersey State Home Builders Association, quoted in John W. Kempson, "Zoning Called Bar to Full Land Use," Newark News, March 4, 1965.

But this criticism has little direct impact on the policies of suburban governments. While pockets of local opposition to fiscal zoning are found in the region, particularly in suburbs with more heterogeneous populations, those who favor liberalization rarely succeed in their encounters with local planning or government bodies. In Princeton Township, for instance, liberal Democrats, civil rights groups, teachers, and moderate-income members of the ItalianAmerican Federation sought in vain during the 1960s to alter restrictive landuse policies in order to foster a balanced and diversified community. Among the opponents of liberalized zoning in 1966 were two successful candidates for local office, one of whom did "not see the point of providing housing for anybody and everybody," while the other "certainly [didn't] want this Statue of Liberty in Princeton."[30] During the same year, a campaign to rezone a large area of Greenwich downward to one-half-acre lots failed, despite the support of local firemen, nurses, post-office employees, and some owners of large parcels of undeveloped land. Defenders of four-acre zoning insisted that their resistance to change had "nothing to do with racial or religious factors. It's just economics. It's like going into Tiffany and demanding a ring for $12.50. Tiffany doesn't have rings for $12.50. Well, Greenwich is like Tiffany."[31]

Local government agencies like Princeton's planning board and Greenwich's zoning commission successfully resist pressures for more intensive land use because they are responsive to the desires of the majority of their constituents. Opposed to rezoning in Greenwich in 1966 were thirty-four local organizations, ranging from taxpayer groups and neighborhood associations to garden clubs. "In Greenwich," observed a landowner who favored change in local four-acre zoning, "no one can get elected unless he swears on the Bible, under the tree at midnight, and with a blood oath to uphold zoning."[32] Once in office, such officials are strongly guided by community sentiment and local self-interest. As the chairman of Princeton's planning board explained in 1966: "Unless there is a groundswell or sentiment for high-density zoning, or through court action, Princeton will remain a residential town of relatively large home lots. . . . [The people of Princeton] would rather live in a low-density suburban area than in a town or city. . . . "[33] As the 1970s came to a close, no groundswell had yet appeared in the vast majority of the region's newer and richer suburbs, most of whose residents continued to prefer spacious zoning.

The Dilemma of Apartments

Zoning for fewer people in single-family residences has accelerated demand for apartments in the suburbs. The rapid rise in apartment construction in the region results both from the growing unavailability of moderately

[30] John D. Wallace and David Thomson, Republican candidates for Township Committee, quoted in Jacqueline Pellaton, "Issue of Low-Cost Housing Divides Princeton Candidates," Trenton Times, October 27, 1966.

[31] Everett Smith, Jr., quoted in Ralph Blumenthal, "Pressures of Growth Stir Zoning Battles in the Suburbs," New York Times, May 29, 1967.

[32] Williams H. Hernstadt, quoted in the above article.

[33] Hans K. Sander, quoted in "Planners Set Forth Objectives," Princeton Packet, March 2, 1966. A few years later, local advocates of lower-income housing were able to prevail over bitter local opposition to secure approval of two small federally subsidized moderate-income housing projects in Princeton Township.

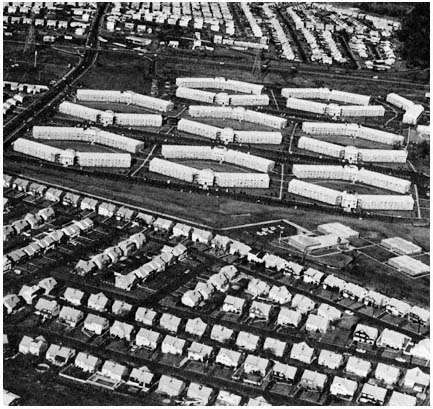

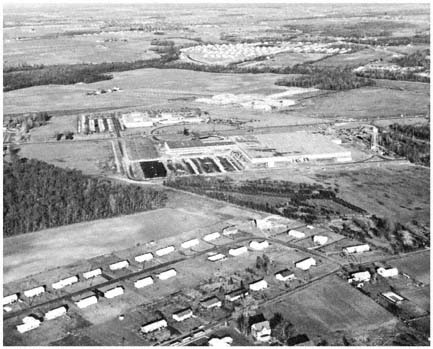

Garden apartments developed in the mid-1960s

in Middlesex County, adjacent to single-family

housing on the small lots typical of suburban

development in the 1950s.

Credit: Louis B. Schlivek, Regional Plan Association

priced single-family homes and changes in the age and income structure of the suburban population. The planning process in suburbia, however, gives relatively little consideration to the role of apartments in meeting the housing needs of the newly married, the elderly, single individuals, and moderateincome families. Instead, as is the case with single-family residences, the realities of the suburban political economy dictate that local officials consider apartment proposals in the context of localized values, with a narrow calculus of costs and benefits.

Apartment construction, however, raises more complex issues within suburban jurisdictions than those posed by moderately priced homes on small lots. Some suburbanites, including local officials who must balance municipal budgets, see apartments as valuable tax ratables whose development can be regulated to produce a net contribution to the local treasury. Others, usually in the majority, consider apartments a threat both to municipal solvency and to community or neighborhood character. As a planner comments concerning the opposition of a Bergen County suburb to

high-rise apartments: "The residents feel they have a sanctuary in Tenafly and they're literally afraid of people moving in. They feel that they have successfully escaped from the central city and they don't want the central city to pursue them."[34] Most suburbanites polled in a 1978 survey opposed new apartment construction, with 76 percent responding negatively to the question "would you approve of more apartment buildings being built in your area?"[35]

Because of these different perceptions within individual suburbs, apartment proposals often become highly contentious issues, at least in comparison with single-family housing questions where internal consensus usually is high, and where conflict tends to be external rather than internal. And because the question of apartments poses a choice between two key suburban development goals—maximizing internal benefits and maintaining the suburban residential image—conflict often is intense and bitter.

The issues and conflicts generated by apartments have produced a common scenario in a number of the region's suburbs during the past decade. The action begins when a developer seeks a building permit or a zoning variance, in order to construct a garden-apartment project in a suburb dominated by single-family residences. Mayors, councilmen, and school-board members often find the proposal attractive because it promises to stabilize or lower the tax rate. But many of their constituents think otherwise, and groups like the Livingston Citizens Against Apartments, the Hillside Homeowners Action Association, and the Madison Township Political Action Group Against More Apartments, are quickly organized. The chief complaints are that school costs and other public expenditures will skyrocket, that traffic congestion and parking problems will intensify, that the character of the community will be changed, and that apartments will attract blacks and soon become slums.[36] The most vehement reaction comes from those in the immediate vicinity of the proposed project who fear that apartments will depreciate the value of their homes. In most jurisdictions, as a Long Island builder notes, "public opposition is unbelievable. There's a desperate need for this kind of housing, but people just go crazy when you talk about building in their town. Four out of five projects I've started have been stopped—people scream that they'll increase traffic, put more kids in the schools, change the neighborhood. They're afraid of any kind of change out here."[37]

In many instances, adverse public reaction kills the initial apartment proposal. Sometimes opposition also sweeps an incumbent administration out of office, as in East Brunswick in Middlesex County and Clark in Union

[34] Isadore Candeub, Candeub-Fleissig and Associates, Newark, N.J., quoted in Gary Rosenblatt, "1962 Dispute Still Persists on Tenafly High-Rise Plan," New York Times, March 19, 1972. The Candeub firm prepared a plan for a New York developer involving the construction of 4,000 apartments and 2.8 million square feet of office space in high-rise buildings on a 274-acre tract in Tenafly. Local opposition prevented the rezoning needed for the project, and led to an effort by Tenafly to acquire the land through condemnation for use as a park.

[35] New York Times, "1978 Suburban Poll" (1978), p. 9.

[36] See State of New Jersey, County and Municipal Government Study Commission, Housing & Suburbs: Fiscal and Social Impact of Multifamily Development, Ninth Report, October, 1974 (Trenton: 1974).

[37] Alvin Benjamin, quoted in Richard Reeves, "A Changing L.I. Is Opposed to Change," New York Times, June 3, 1971.

County. Often public antipathy to apartments and the kinds of people who live in them produces prohibitions on future apartment construction. In the 1960s, only I percent of the residential land in the region's suburbs was zoned for multiple dwellings, and much of this was located in the older suburban jurisdictions. In Westchester, apartments could be built on almost 5 percent of the 55,000 acres of all land zoned for residential use in cities and villages, but on less than 1/2 of 1 percent of the 198,000 acres assigned to residential use in the less-intensely settled towns where most future development would occur. Only 2,000 of the 400,000 acres of undeveloped residential land in Morris, Somerset, Middlesex, and Monmouth counties were zoned for multiple dwellings in 1970.[38]

In many communities, prohibitions on multiple dwellings are only a prelude to the second act of the apartment drama. This phase often starts when a developer or landowner brings suit after his application to build apartments has been rejected. Court orders sometimes result which force a locality to rezone for apartments or remove a moratorium on apartment construction. In other suburbs, rising municipal burdens produced by intensive single-family development lead to renewed interest in apartments on the part of local officials, who seek to demonstrate to their constituents that under the proper conditions apartments will provide a favorable ratio of local property-tax revenues to public costs, especially for education. One source of reassurance is a study by George Sternlieb which found that a community can profit from one-bedroom and efficiency apartments, but must severely limit the number of multiple-bedroom units if it does not want school costs to exceed property tax revenues from the project.[39] These and similar findings are reflected in the garden apartment regulations drafted by suburban planners and their private consultants. A typical ordinance, like that of Hillside or East Brunswick, requires 80 percent of the apartments to have one bedroom or less. Table 14 shows the pattern of restrictions in Middlesex County in 1970.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[38] See Economic Consultants Organization, Zoning Ordinances and Administration, p. 16; and Williams and Norman, "Exclusionary Land-Use Controls: The Case of Northeastern New Jersey."

[39] See George Sternlieb, The Garden Apartment Development: A Municipal Cost-Revenue Analysis (New Brunswick: Bureau of Economic Research, Rutgers—The State University, 1964), p. 14.

Once an apartment ordinance is proposed, another battle ensues, with the threatened neighborhood leading the opposition, frequently taking the conflict to the courts. Nor does the controversy end with the construction of an initial apartment project, since pressures often develop for a moratorium on further apartment development so that the local government may evaluate the impact on taxes and municipal services of those that have been built.

In a few suburbs, high-rise apartments produce a third act, replete with renditions of many familiar themes from earlier conflicts over tax ratables, school costs, and community character. Given the limited amount of land available for multiple dwellings in the region's suburbs, the issue of high-rise apartments may follow hard on the heels of garden-apartment settlements. This was the case in Cedar Grove in Essex County, where acceptance of garden apartments was followed by a developer's proposal to build high-rise apartments on the crest of First Mountain. And when high-rise controversies are resolved, the zoning regulations closely resemble those designed to maximize suburban revenues from garden-apartment development. In Port Chester in Westchester County, for example, only 253 of 981 units in three apartment towers have as many as two bedrooms.

Of course, many variations in this scenario are found in a region as large and complex as New York. Prohibitions on apartments have been maintained successfully by some communities, typically those that can afford to value their single-family residential character more highly than the municipal profit promised by one-bedroom apartments. Others have demonstrated skill and foresight in adopting restrictive apartment regulations that effectively foreclose the typical garden apartment, with its monotonous box-like buildings, crowded acreage, and unattractive site planning. At the other end of the spectrum are less sophisticated suburbs whose initial response to apartments has been highly permissive. These communities typically already had severe fiscal problems arising from intensive single-family development, so indiscriminate apartment construction threatens municipal disaster. In Parsippany-Troy Hills, minimal controls on garden apartments led to explosive growth that doubled both the population of the Morris County community (from 25,000 to 50,000) and many municipal costs between 1960 and 1967. This led the hard-pressed local government to adopt a two-year moratorium on new apartment development in 1966.

For many suburbs, however, the scenario has been shortened, as knowledge about the costs and benefits of apartments is spread through the region by planning consultants, county planning agencies, and professional journals, as well as by the well-publicized experiences of Parsippany-Troy Hills and other unfortunate suburbs that failed to adopt apartment controls designed to maximize internal benefits before the arrival of the developers. Almost every suburban jurisdiction that permits multiple dwellings has by now adopted bedroom restrictions. And for most, garden apartments constructed under these constraints have proved to be profitable in terms of tax revenues. Madison—a Middlesex County suburb that limited two-bedroom apartments to 20 percent of the total in a development—collected 13.5 percent of its 1970 school taxes from its ten garden-apartment developments, which housed only 5.8 percent of the school population. As a result, apartments contributed $326 per unit to school taxes each year while generating educational outlays of only $135 per unit, for a school surplus of $191 for each

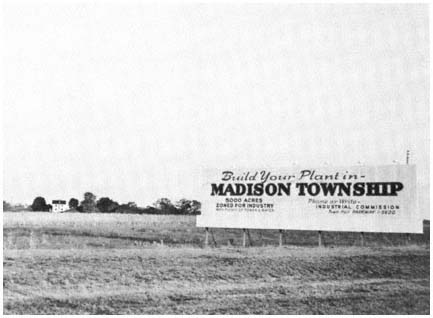

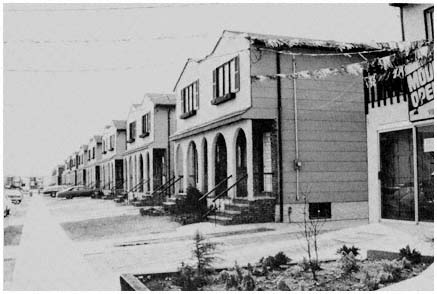

The quest for additional tax revenues stimulates aggressive

efforts to lure industrial development to the suburbs.

Credit: Louis B. Schlivek, Regional Plan Association

apartment. By contrast, an average of $675 in school taxes was collected from single-family homes in Madison, while $955 was spent to educate the children housed in the typical single-family dwelling.[40]

The Right Kind of Industry

In the great suburban game of increasing taxable property without assuming responsibilities for the education of large numbers of children, the most dramatic opportunities for the maximization of internal benefits are provided by industrial and commercial decentralization. As indicated in Chapter Two, such opportunities are increasingly numerous, since almost every form of economic activity in the region has been moving outward. To be sure, a few suburbs continue to value their residential character above the potential benefits of industrial parks, corporate headquarters, research laboratories, and shopping centers. But most cannot resist the lure of valuable properties that by themselves add no pupils to the local school rolls. As the mayor of a suburb that attracted a major office facility in 1971 explains: "With rising costs, a town can't survive anymore strictly on residential property taxes. I.B.M.'s coming was very timely. While it hasn't lowered our tax rate, it certainly has stabilized it."[41]

[40] See Marshall R. Burack, "Apartment Zoning in Suburbia," Senior Thesis (Princeton University, 1971), pp. 112–114.

[41] Mayor Thomas Pawelko, Franklin Lakes, N.J., quoted in "I.B.M. Is Proving a Good Neighbor in Affluent Bergen Town," New York Times, May 20, 1973.

Because of these considerations, large amounts of vacant land in the suburbs have been zoned for industrial development—far more, in fact, than industry is ever likely to need, especially considering the inaccessibility of some suburban "industrial" zones. For many suburbs, however, zoning land for industry that will never materialize is also an attractive strategy, since it serves as an effective way to prevent or forestall unwanted residential development.

Because the objective of attracting industry is to maximize internal benefits to the particular community rather than to serve the interests of employers or employees, suburbs that zone land for industrial purposes rarely make provision for housing those who will work in the community. In 1970, for example, in the area around Princeton, local governments had reserved enough land for business uses to support 1.17 million jobs. But under existing zoning, housing could be constructed for only 144,000 families, and almost all of it would be priced far beyond the reach of the average industrial wage-earner.[42]

Furthermore, most suburbs want only certain kinds of industrial or commercial development. The typical suburban goal is to attract industry that will provide tax revenue without compromising the community's residential character. Under these circumstances, the ideal industry, as a Westchester planner wryly notes, "is a new campus-type headquarters that smells like Chanel No. 5, sounds like a Stradivarius, has the visual attributes of Sophia Loren, employs only executives with no children and produces items that can be transported away in white station wagons once a month."[43] The trouble with this kind of industry, of course, is that the supply falls far short of the demand. Moreover, the most desirable industrial and commercial facilities seek the most attractive locations. Consequently, factors such as favorable topography, high-quality residential development, and good transportation facilities tend to overshadow local industrial strategies in decisions concerning the location of suburban office and research facilities. In the process—as with other aspects of suburban development politics—the wealthier communities tend to secure the most desirable development, while the poorer suburbs have great difficulty in maximizing internal economic benefits without seriously compromising residential goals.

At the other end of the scale in terms of suburban desirability is heavy industry, with its pollutants, heavy transport requirements, and unskilled work force. Given the inhospitality of the suburban value structure and political economy to lower-income residents, the latter factor is particularly important. As former Westchester County Executive Edwin J. Michaelian explained: "We do not have a pool of personnel available for heavy industry . . . [we] wouldn't know where to put, where to house a large group of people who were to come in with a manufacturing industry. . . . "[44]

Occasionally, however, geography and restrictive zoning permit a residential suburb to obtain the benefits of heavy industry without sacrificing

[42] See Middlesex-Somerset-Mercer Regional Study Council, Housing and the Quality of our Environment (Princeton, N.J.: 1970).

[43] Sy J. Schulman, Westchester County Planning Commissioner, quoted in Merrill Folsom, "Westchester Finds Influx of Business a Worry," New York Times, April 18, 1967.

[44] Quoted in Martin Arnold, "Westchester Cites Industrial Goals," New York Times, February 20, 1967.

residential amenities or incurring the burdens of servicing blue-collar residents. This is the case in Mahwah in northwest Bergen County, whose major source of revenue has been a Ford Motor plant that is isolated from the remainder of the residential suburb by the Erie-Lackawanna Railroad and a major highway. Within Mahwah, land-use restrictions ensured that local housing would be beyond the means of Ford's 5,200 workers. Confronting similar restrictions in neighboring communities, most of the Ford workers had to travel long distances to their jobs. On the other hand, the factory's presence helped provide Mahwah's middle-income residents with high-quality public services at relatively low property tax rates compared with neighboring communities.

For their part, business firms are just as eager as suburban officials to avoid the tax burdens imposed by a surfeit of families with school-age children. When space, market, transportation, and labor-force requirements offer business a choice of sites—as they frequently do in a region as large as New York—lower taxes are often the determining factor in industrial and commercial locational decisionmaking. A study of the effects of local taxes on the location of business by the U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations concludes:

among local governments within a State and especially within a metropolitan area, tax differentials exert discernible plant location pull—the industrial tax haven stands out as the most conspicuous example. In almost every metropolitan area there exist wide local property tax differentials—a cost consideration that can become a "swing" factor in the final selection of a particular plant location.[45]

As a consequence, lower-tax suburbs enjoy an initial advantage in the quest for attractive industry and commerce. Moreover, municipal success in securing industrial and commercial development tends to be cumulative, since the lower taxes made possible by the initial successes help attract additional industry. Finally, taxes combine with transport, topography, and other factors to produce clusters of suburban industry and commerce, which in turn contribute to the mismatch between resources and needs discussed earlier in this chapter.

From industry's perspective, of course, the ideal suburb would have no residents at all. In the New York region, a number of companies enjoy the manifest benefits of such a location in Teterboro in Bergen County. Teterboro was the brainchild of Alexander Summer, a real-estate developer who reasoned correctly that business would be eager to buy land in a municipality whose lack of residents would ensure a low and stable tax rate. Summer's thesis was that if he and his associates purchased most of the homes in sparsely settled Teterboro, "along with all the remaining undeveloped land in the borough, we could reasonably expect full municipal cooperation instead of the bickering and frustrations that a developer usually encounters in dealing with the governing bodies of small communities." Once the homes were

[45] Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, State-Local Taxation and Industrial Location (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1967), pp. 78–79. Italics in original omitted.

purchased, rents were drastically reduced to secure the support of the tenants, who included the mayor, most of the councilmen, and a majority of the municipality's residents. After Summer and his associates acquired the land, "the first official action of the mayor and council (at our request) was to zone the whole community against residential use."[46] In 1977, two dozen people lived in Teterboro, which has no schools, one of the lowest municipal tax rates in New Jersey, and public services devoted almost exclusively to servicing the needs of its thirty-five major industries, which employ 24,000 nonresidents.[47] For an official of the Bendix Corporation, Teterboro's largest employer and major landowner, the borough was not "a tax haven," but rather "a community designed for industry."[48]

Not the least of the advantages offered by a municipality like Teterboro is the absence of residents worried about the encroachment of industry on residential values. When industry comes to a suburb with people, on the other hand, opposition is common and conflict often intense. The prospect of industrial and commercial development, like apartments, forces suburbanites to choose between maximizing tax revenues and preserving the residential character of their community. "We realize that there are a lot of problems in living with industry," acknowledges the mayor of a suburb that has attracted a number of major firms, "but we were willing to do it because of the tax benefits to residents of the community."[49] Also resembling the apartment controversies is the conflict engendered by industry between the interests of the community as a whole and the particular neighborhood most affected by industrial or commercial development. The result, as illustrated by the recent experiences of Pepsico, Inc., E. R. Squibb & Company, and the Western Electric Company in the New York region, is that even the most desirable industrial property rarely receives a unanimous welcome in the suburbs. In each of these cases, the corporation sought an attractive location in a high-quality residential area, and was strongly opposed by affluent local residents determined to preserve the character of their neighborhood.

For the estate owners in Purchase, in Westchester County, Pepsico's plan for a $12 million office building for 1,000 employees on a 112-acre site zoned for 2.5-acre residences was "progress with desecration."[50] For the rest of the town of Harrison, however, Pepsico was a prize that would generate four times as much local revenue as residential development on the same site,

[46] Quoted in John R. Lancelotti, "Albanese Demands End of Teterboro," Newark News, January 3, 1966.

[47] In 1976 Teterboro's tax rate was 65¢ per $100 of property, the second lowest rate in northern New Jersey. All 24 of Teterboro's residents lived in housing owned by the Bendix Corporation, including the mayor, all the members of the borough council, and a number of municipal employees. Teterboro's one school-age child in 1977 was enrolled in nearby Hackensack, at a cost of $4,400 for the community's industrial taxpayers.

[48] Martin Paskoff, northeast regional counsel, Bendix Corporation, quoted in William Tucker, "A Taxpayer's Camelot in New Jersey," New York Times, February 20, 1977.

[49] Mayor Frederick Knox, East Hanover, N.J. Located in Morris County near the junction of I-80 and I-280, East Hanover was the site of major facilities of Sandoz Chemicals, Norda Chemicals, and Tempco, as well as the international headquarters of Nabisco Corporation. As a result of its substantial business tax base, East Hanover had the lowest tax rate in Morris County in 1976.

[50] Lawrence Robbins, Purchase Association, quoted in Merrill Folsom, "New Zoning Voted for Pepsico Site," New York Times, May 23, 1967.

without requiring new schools or other public service improvements. In the past, opposition from Purchase residents had excluded International Business Machines, a racetrack, and a shopping center from their manicured acres. But the campaign against Pepsico—which included an abortive attempt to secede from Harrison—failed as the town's broader interests prevailed over those of its wealthiest residents. Three months after Pepsico revealed its plans, the Harrison town board approved a zoning change to permit commercial buildings in areas previously restricted to private estates, provided the facilities were surrounded by at least 100 landscaped acres.