PART IV—

MANUSCRIPTS PRODUCED DURING THE REIGN OF CHARLES VI

Chapter Eight—

The Legacy of Charles V

After the death of Charles V in 1380 the political situation in Paris changed. Charles VI succeeded to the throne at the age of 12 in a government that violated the ordinance governing the regency drafted by Charles V in 1374. Charles V had planned for a balanced government in which Charles VI's uncles, Philip of Burgundy and Louis of Anjou, would control separate areas and counter each other's ambitions until Charles was 14.[1] Instead, the regency council was dominated by Philip the Bold, duke of Burgundy, after Louis of Anjou departed for Naples in 1381. From Charles V's death until Charles VI finally took control in 1388, the French dukes entrusted with the regency concentrated more on promoting their own interests than on serving the state.

When Charles attained his majority in 1388, the structure of government changed. The young king turned away from the dukes and toward advisors who had worked for his father; these counsellors began to provide stability and continuity in policy. However, shortly after he began to rule independently, Charles was beset by a bout of mental illness in 1392.

This illness was perhaps the most important factor shaping the political climate of Charles VI's reign. He seemed to recover from his first crise by September of 1392 but had a second attack in June of 1393 that lasted until January 1394. This pattern of illness and remission continued; in 30 years Charles had about 43 "absences," as they were euphemistically called in the documents.

Charles's mental illness posed special problems for the court and the government of France. Frequently, when he was "absent," Charles did not know himself or his family. The dilemma that the court faced centered on the fact that, at least in the beginning, Charles seemed capable of governing between his attacks.[2] For a period of approximately 20 years—from the onset of the condition in 1392 until around 1414 when it overcame the king—the members of the French court had no way to gauge whether Charles could govern at any given time. The question of who should govern was of central importance, and there were diverse opinions as to the correct answer.

One solution would have had the royal heir act as regent, but Charles's sons were sickly. His first son, Charles, died in 1386 at the age of three months; his second son, also called Charles, died in 1401 at the age of 9; a third son, Louis of Guyenne, died in 1415 at 18; and a fourth, John of Touraine, died in 1417 at 17. The only son to survive Charles VI, another Charles, was disinherited in 1420. Thus government by the heir was possible only during the second decade of the fifteenth century, when Louis of Guyenne was dauphin.

After the failure of a series of regency councils that governed for the underage dauphins, France succumbed in 1409 to a civil war.[3] With the exception of Louis of Bourbon, an uncle of Charles VI who remained a royalist, most of the king's relatives and the members of the royal court joined one of two factions: the Burgundian, headed at first by Charles VI's uncle, Philip the Bold, and then, after 1404, by Philip's son, John the Fearless; and the Orléanist, initially led by Charles VI's brother, Louis of Orléans, and, after Louis's assassination in 1407, by Louis's son, Charles of Orléans; by Charles's father-in-law, Bernard of Armagnac; and periodically by John of Berry.[4]

By 1404 the political fight for control broadened to include the dauphins—especially Louis of Guyenne, who lived to be almost 19 years old—and the dauphin's mother and primary guardian, Queen Isabeau of Bavaria. Indeed, Louis became so powerful that by 1409 he was empowered to act in the king's stead when Charles was "absent."

The pattern of literary patronage also changed when Charles VI succeeded to the throne. Charles V had been a sophisticated literary patron whose commissions for translations or for the composition of new texts reflected his political thought.[5] Charles VI was very different from his father, apparently sharing none of his concern with political theory. As Monfrin notes, patronage at court during Charles VI's reign was more preoccupied with "responding to the private interest of individual patrons than with serving the intellectual formation of a group."[6] Louis of Orléans, Charles VI's brother, was the only member of the royal family whose patronage was influenced by Charles V's example. Louis commissioned copies of many of the political and literary texts translated for his father, in part to present himself as the logical choice as successor once Charles VI's illness made evident his inability to govern.[7] Even when politically motivated, Louis's commissions also responded to his private interests.

Jacques Krynen demonstrates how the model for the production of political literature during the time of Charles V altered under Charles VI. During the reign of Charles V,[8] members of the royal entourage wrote most of the polemical literature, frequently at the express command of the king. While Charles VI reigned, intellectuals outside the court joined those who worked for the court to produce a literature that focused on the person of the king. Especially noteworthy is the consistency of focus that Krynen found in these writings, whether notarial, courtly, or academic. None questioned Charles VI's ability to rule, despite his increasingly obvious insanity and the dire state of the country, where civil war raged and the Hundred Years' War with England dragged on. Rather, most political writers manifested a loyalty toward the monarchy and the person of the king that impelled them to seek new ways to strengthen the Christian kingship of France and to urge the powers who actually governed France—the princes of the blood, the queen, and the dauphin—to do the same.

By the early fifteenth century, political theory had become the province of the royal chancery or, less frequently, of the University of Paris. Tracts written by such authors as Jean de Montreuil, a member of the chancery, or by Jean Gerson, chancellor of the university, formulated the political rhetoric of the French government and the factions that battled for power within it.[9] These unillustrated tracts and sermons, rather than contemporary copies of the chronicle, are the successors to the political program of Charles V's Grandes Chroniques .

For example, Jean de Montreuil's Traité contre les anglais of 1413 built upon the political arguments first formulated in Charles V's 1378 speech before the Holy Roman Emperor, adapting almost verbatim its repudiation of English pretensions to the French throne. Summarized in Charles V's Grandes Chroniques and subsequently in families E and F of the Chronique abrégée and Christine de Pizan's biography of Charles V, this speech remained the basis for anti-English treatises throughout the reign of Charles VI. A chancery dossier, the Mémoire grossement abrégée , compiled by Jean de Montreuil in 1390, preserves the inverted chronological structure established by Charles V's speech, discussing Edward III's homage to Philip of Valois before Henry III's homage to Saint Louis. It then cites the "c'est assavoir" clause in the Treaty of Brétigny, which was annotated in Charles V's manuscript, and the Black Prince's killing of Palot and Chaponval, the imprisoned representatives of Charles V. Subsequently, this chancery dossier became one of the sources for the Traité contre les anglais , which exists in two French redactions and one Latin redaction dating between 1413 and 1416.[10]

Other authors, like Christine de Pizan or Philip de Mézières, shared Jean Gerson's firm belief in the monarchy.[11] The work of these royalists exhorted the king to encourage good government and counseled the queen and princes of the fleur-de-lis to work for peace and for the good of France. Christine de Pizan's writings in particular focus on themes that became important in copies of the Grandes Chroniques produced during the second half of Charles VI's reign.

The pictures in Grandes Chroniques manuscripts produced from the 1380s through the first quarter of the fifteenth century parallel the literary development Krynen describes. After an initial period in which royal and courtly manuscripts imitated the chronicle produced for Charles V, books created for all levels of patronage began to concentrate on the monarchy. The sheer number of manuscripts that survive from this era attests to the transformation of the Grandes Chroniques from royal history to national history. Cycles of illustration range from the mass-produced to the carefully crafted, yet all celebrate the religion royale . Although none question Charles VI's ability to govern, a small group recognize the realities of government during the latter years of Charles VI's reign and introduce pictorial models that establish precedents for the involvement of the dukes, queen, and dauphins in government.

A handful of Grandes Chroniques produced in the last quarter of the fourteenth century are conservative, drawing from Charles V's manuscript for both the layout and content of their miniatures.[12] Although closely related, the cycles from these manuscripts differ significantly from Charles V's chronicle. None emulate the sophisticated layering of miniatures that added to the political content in Charles's codex, even though the editor of at least one of them clearly understood the structure of Charles V's book, whose text he copied.

The earliest Grandes Chroniques (B.N. fr. 10135) from this group belonged to Charles VI and was probably painted for him during Charles V's lifetime, since the Master of the Coronation of Charles VI, the artist of the frontispiece of this manuscript, painted several miniatures in the third stage of Charles V's Grandes Chroniques . Its cycle is almost identical to Charles V's as it appeared at the end of the first stage of execution. Of all the manuscripts based on Charles V's book, it alone copies the frontispiece with its anti-imperial overtones and the dense cycle illustrating the life of Saint Louis, the saintly model for French kingship. It thus

shares the emphasis on French independence and on royal models that dominates Charles V's book prior to 1375.

Because this chronicle was probably presented to Charles VI while he was dauphin, it provides insights into the education of a prince during the late fourteenth century. Its text offers historical models for the royal heir, while its pictures provide ideological models based on certain concerns of Charles V. These images thus serve a purpose similar to that of Philip de Mézières's Songe du vieil pelerin or Christine de Pizan's Livre des fais et bonnes meurs du sage roi Charles V , which are in part panegyrics on Charles V written during the early years of Charles VI's reign and designed to encourage good government.[13]

Three other copies of the chronicle (B.N. fr. 2608; Vienna, ÖNB 2564; and Lyon, B.M. 880), painted in the 1390s or in the early years of the fifteenth century, show how important the model of Charles V was to Charles VI and the court even 10 to 15 years after his death. On the basis of their iconography, these three books form a group that differs in pictorial content from Charles V's manuscript.

The most important manuscript (B.N. fr. 2608) from this group was painted for Charles VI after he became king. Significantly, it is the only chronicle whose text demonstrably copies Charles V's manuscript, but does not do so indiscriminately. Indeed, the way in which the editor incorporates some of the marginal notes relating to Charles V's speech proves that sophisticated readers understood the complex interrelationship of text and images in Charles V's book but did not necessarily find it relevant to their needs.[14] Because Charles VI's manuscript contains the shortened description of the emperor's visit in 1378, omitting the royal speech, the scribe copied only those notes that were comprehensible in the text of the shortened chronicle. He also transcribed marginal annotations commenting on select clauses in a letter from the English king (Charles V, ch. 13) but omitted the charters about homage and their illustrations, the note recording the deaths of the messengers sent to the Black Prince, and the note concluding that the French were justified in recommencing war with England. These notes and the substituted texts and miniatures on homage in Charles V's manuscript had provided documentation for the content of Charles V's speech; in a manuscript without the summary of the speech they would have been superfluous.

Although the designer of Charles VI's Grandes Chroniques (B.N. fr. 2608) had access to Charles V's complex program and understood it, he chose to omit much of it and focus instead on Saint Louis, as had Charles VI's earlier chronicle (B.N. fr. 10135). He used Charles V's manuscript as a guide for the layout of illustrations. Of the 76 miniatures in B.N. fr. 2608, only 15 do not copy images in Charles V's Grandes Chroniques . Yet, in many ways, what was left out of this illustrative program is as telling as what was included. Most images dealing with Charles V's rise to power and with English strife were omitted, perhaps because France was negotiating peace with England throughout the 1390s. Indeed, the English scenes that do appear are almost laudatory. They include the English encounter with the French outside Reims (fol. 481v); the Treaty of Brétigny (fol. 483v); and the coronation of Richard II (fol. 521v), Charles VI's future son-in-law.[15]

The most innovative aspect of the decorative cycle in Charles VI's second copy of the Grandes Chroniques is its emphasis on Saint Louis, a focus it shares with earlier books produced for Charles V and Charles VI but handles very differently. Two iconic images of Louis IX in this chronicle stress special qualities of French government. The most distinctive is an illustration to the prologue (Fig. 92) in

Figure 92

Presentation of chronicle to Saints Louis and Denis. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2608. fol. 1. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

which a monk kneels to present the chronicle to Saint Louis and Saint Denis. Although he is not portrayed in the scene of presentation, Charles VI is alluded to on this folio, since the crowned arms of France moderne appear at the bottom of the page supported by two cerfs volants , winged stags, a favorite emblem of the king in the 1380s and 1390s.[16] The scene of presentation to the two saints is one of the few scenes that do not appear in the model. In fact, among all the copies of the Grandes Chroniques that I have inspected, it is the only scene to represent a presentation of the book to someone other than the king.

On one level the inclusion of these two saints is not surprising. Throughout the Middle Ages, Saint Denis was both a royal and a national saint.[17] Indeed, the prologue that this scene illustrates represents Saint Denis's protection of France as a reward for France's holiness. Even if Saint Louis failed to achieve the same level of national popularity, his cult was strong in the Parisian basin, and he was a royal model for government.[18] The pairing of these saints can thus be seen as an expression of royal and national devotion.

Yet Louis IX had rarely been associated with Saint Denis in a visual context before this image. To my knowledge, the miniature in Charles VI's Grandes Chroniques constitutes one of the earliest secular examples of Saint Denis and Saint Louis paired alone. When they do appear together, they are most frequently portrayed as protectors of the French royal house in politically charged religious images dating from the reign of John the Good to that of Charles VII.[19] In this miniature, however, the saints replace the king, a substitution that must have been particularly appropriate during Charles VI's absences in the 1390s.

Saint Denis had long been considered the protector of royal health, a responsibility in which Saint Louis, as royal saint, participated. As early as 1335 when Charles VI's grandfather, John, duke of Normandy, was ill, relics of Christ and Saint Louis preserved at Saint-Denis were credited with his cure.[20] In 1392 Charles VI himself gave a châsse to house relics of Saint Louis to the abbey of Saint-Denis in thanks for intervention in his illness. Thus while the substitution of these saints for the king in the scene of presentation in Charles VI's book certainly evokes the idea of holy sponsorship of the history contained in the manuscript, it may also evoke the idea of heavenly protection for the king who was so often "absent"—both from this picture of presentation and from his people.

The second picture of Saint Louis (Fig. 93) at the beginning of Louis's life simultaneously glorifies the holy patron of France and sacred character of French kingship. Nimbed and crowned, Saint Louis sits on a faldstool and holds a scepter topped by a fleur-de-lis as two praying angels hover to either side. Although it is customary for kings to hold scepters when enthroned in state, the gesture is given special importance in this picture where Saint Louis clasps his scepter in a cloth-draped hand.

No precise textual source explains Louis's gesture, which signals the sacredness of the symbol of his rule. Although the second chapter of Louis's life describes his coronation, the description does not explain the presence of the angels, the halo, or the holiness of the symbol of government—the scepter topped by a fleur-de-lis. The closest source in the chronicle for this picture is a passage in Louis's life that explains the significance of the fleur-de-lis and describes how crucial the virtues symbolized by its three leaves are for good government: "The leaf which is in the middle symbolizes Christian faith for us, and the other two beside it

Figure 93

Saint Louis enthroned. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2608. fol. 311v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

symbolize learning and chivalry which should always be prepared to defend the Christian faith. And as long as these three—faith, learning, and chivalry—reside in France, the realm of France will be strong and firm, full of wealth and honor."[21]

The image at the beginning of Louis's life thus merges two ideas: the concept that the French king was the rex christianissimus who governed a holy realm and the idea that the fleur-de-lis, miraculously given to the French, confirmed God's favor. Both ideas had formed part of French political theory since the reign of the last Capetians, but they emerged with special power in the writings of the university community during the reign of Charles VI, most notably in Jean Gerson's letters and sermons written during the 1390s.[22]

The theme of France's holy kingship and the exhortation to good government implicit in this iconic miniature differ from the emphasis on Louis's life as a model of kingship presented by the pictures in Charles V's manuscript and in Charles VI's earlier copy of the Grandes Chroniques (B.N. fr. 10135). Both earlier books present several facets of Louis's life as models. For instance, the inserted frontispiece to the life of Saint Louis in Charles V's manuscript (Fig. 87) presents Louis as a model of kingship, of devotion, and of charity and is thus an appropriate introduction to the pictorial cycle in that chronicle. The iconic picture of Saint Louis from Charles

VI's later copy of the chronicle, on the other hand, draws the reader's attention to the themes of good government and the ideals of kingship that were important in the era when Charles VI took control of the government only to fall ill.

A brief consideration of the other two manuscripts from this group of three reinforces the special nature of the representations of Saints Denis and Louis in the king's Grandes Chroniques . One of the manuscripts (Vienna, ÖNB 2564) that copied Charles VI's book belonged to John of Montaigu, the grand-maître of France under Charles VI.[23] The second (Lyon, B.M. 880) was probably also a courtly commission and may have been the direct model for John of Montaigu's book.[24] Although the pictorial layouts of these chronicles are almost identical to that in the king's manuscript, their individual miniatures differ significantly in content. Thus a traditional image of a monk composing the text replaces the presentation miniature with Saint Louis and Saint Denis, and many of the supernatural and holy elements of the miniature from the beginning of Saint Louis's life are suppressed. Clearly, the images featuring Saint Louis were seen as particularly appropriate for the king, since in the rest of their cycles these two manuscripts copied Charles VI's book closely. Indeed, the interrelationship of the cycles in these three copies of the Grandes Chroniques signals the continued authority of royal copies of history early in the reign of Charles VI.

Chapter Nine—

Popular Manuscripts and the Religion Royale

While Charles V's and Charles VI's lavish manuscripts were garnering a limited courtly following, less costly copies of the Grandes Chroniques were being produced by booksellers for the growing Parisian book trade. First owners are known with certainty for only two surviving manuscripts: one book (Ste.-Gen. 783) belonged to Regnault d'Angennes, the chamberlain of the dauphin, Louis of Guyenne; and a second (B.N. fr. 6466–67) was presented to John of Berry by Jean de la Barre, the receiver general of finance in Languedoc and the duchy of Guyenne.[1] If these are representative owners, then they did not differ radically from the owners of manuscripts that copied royal models.

Illustrations in manuscripts produced for the book trade are independent of royal models and of one another. Perhaps because the royal library was out of bounds for the average Parisian bookseller, each editor seems to have developed new solutions to the problem of illustrating the Grandes Chroniques . Yet these manuscripts do have some elements in common. They have shorter cycles of decoration, which average between 30 and 50 miniatures and often have a looser relationship to their text than the cycles in royal manuscripts or those based on royal models. Miniatures in these cycles almost always mark the beginning of a king's reign and frequently illustrate a vivid story from one of the chapters. For instance, the beginning of the fifth book of the chronicle is illustrated in two iconographical groups by a picture of King Dagobert supervising the construction of the abbey of Saint-Denis, an event recounted in the ninth chapter. In some groups miniatures have little textual basis; in others they are based on erroneous readings of the text. For instance, certain copies of the Grandes Chroniques transform the Empress Richilda, who presented a sword and scepter to Louis the Stammerer, into an emperor.[2]

A comparison of three versions of the Grandes Chroniques —Valenciennes, B.M. 637, W. 138, and B.N. fr. 2604—offers a rare glimpse into the activities of the Parisian book trade at the end of the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth century, when Charles's illness had been recognized but an overt political struggle had not yet developed.[3] These books, whose earliest owners are unknown, include a version of the chronicle that is related to Thomas of Maubeuge's early fourteenth-century manuscript, but they also provide a fully rubricated continuation to the accession of Charles VI in a version that had become

Figure 94

Charlemagne presents Louis the Pious to a bishop.

Grandes Chroniques de France . Valenciennes,

Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 637, fol. 134.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Valenciennes.

standard by the late fourteenth century. Furthermore, they share unconventional iconography whose subjects are described in notes to the illuminator preserved in the margins of the manuscript from Valenciennes.[4]

A comparison of individual pictures not derived from their texts demonstrates the close relationship between the three cycles and these directions to the illuminator. For example, the Valenciennes miniature illustrating the life of Louis VII portrays a scene of homage that is never described in the life of that king but nonetheless appears in identical form in the book from Paris. Similarly, a peculiar illustration from the third book of Philip Augustus's life, which may illustrate the pope ordering Amaury de Bene to cease his heretical preaching, appears only in these three copies of the Grandes Chroniques .[5]

Even the textually based pictures in these manuscripts are nearly identical. For instance, the picture introducing the life of Louis the Pious in the manuscripts from Valenciennes and Paris (Figs. 94 and 95) follows the directions recorded in the margins of the former manuscript: "How the king, accompanied by two nobles directly behind him, holds his young son by the hand and presents him to two bishops and the first [bishop] blesses him and behind him [the bishop]

Figure 95

Charlemagne presents Louis the Pious to a bishop. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2604, fol.

145. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

is a chaplain."[6] Furthermore, all three manuscripts have identical scenes for the first book of the life of Philip Augustus (Figs. 96 and 97), an image that was also described precisely by the marginal note: "An armed king without a helmet sits on a bench; many armed men with shields behind; right in front are three kneeling and bareheaded men who present swords by their points and cry for mercy."[7]

The iconographical relationship between the three manuscripts is unquestionable, but the reason for the relationship is not totally clear. For instance, not every illustration in the three chronicles is based upon the Valenciennes notes; in the Valenciennes chronicle itself, 4 of 25 miniatures have no marginal directions; and in the Paris and Baltimore manuscripts 12 of 31 and 5 of 12 pictures, respectively, are independent of the directions preserved in the Valenciennes book.[8]

Indeed, even scenes that derive unquestionably from the directions differ in detail from one book to another. This fact clearly rules out the possibility that one book copied another and suggests instead that each responded independently to similar instructions. For example, in the Valenciennes and Paris manuscripts the illustration to Book III of the life of Charlemagne follows a direction that states: "How the king is in front and several nobles before him, and before him

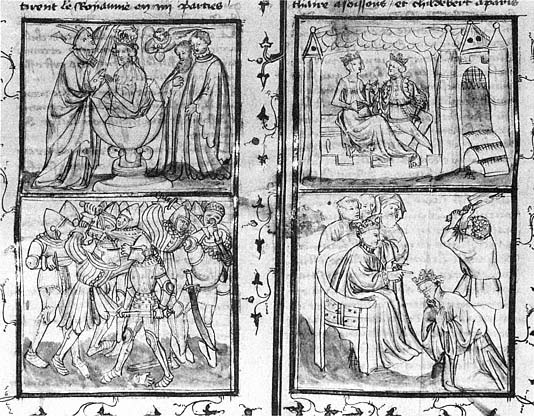

Figure 96

Surrender of Le Mans or Tours. Grandes Chroniques de France . Valenciennes,

Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 637, fol. 237v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Valenciennes.

[is] a castle and little men who construct around [it] and one is on a ladder and another low [on the ground] who cuts stone."[9] The Valenciennes miniature (fol. 111) represents Charlemagne, the nobles, the castle, and two masons, but omits the ladder. The Paris miniature (fol. 118) includes nobles, the castle with two masons, and a ladder, but omits Charlemagne. Both artists were confronted with the problem of selecting elements from the written direction that would fit within the limited space of the miniature; the Valenciennes artist chose to concentrate on Charlemagne as he commissioned the castle and thus cut back on the scene of construction, whereas the Paris artist focused on the details of construction and therefore had no room for Charlemagne.

Because seven different artists worked on these three cycles, it is unlikely that they are based on shared visual models preserved in artists' workshops. Only two

Figure 97

Surrender of Le Mans or Tours. Grandes Chroniques de France . Walters Art

Gallery, W. 138, fol. 15. Photograph: Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore.

artists worked on more than one book; an artist (W. 138, Artist I) who painted four miniatures in the Baltimore chronicle painted one in the Valenciennes book (Valenciennes, Artist IV), and the artist (Valenciennes, Artist I) who painted 21 images in the Valenciennes manuscript is close if not identical to the painter (B.N. fr. 2604, Artist III) of 26 pictures in the chronicle in Paris. Each of the other five artists worked on one of the three manuscripts: two worked on the chronicle in Valenciennes (Valenciennes, Artists II and III), two on the chronicle in Paris (B.N. fr. 2604, Artists I and II), and one on the chronicle in Baltimore (W. 138, Artist II). With one exception (Valenciennes, B.M. 637, fol. 154, completed by Valenciennes, Artist III), these artists worked in separate gatherings, so it is quite unlikely that they saw one another's work. The similarities in the iconographical programs of the Grandes Chroniques in Valenciennes, Baltimore, and Paris are therefore better interpreted as productions supervised by the same libraire than as productions by artists working in the same workshop. Apparently the libraire who supervised these manuscripts maintained a master list of directions to Grandes Chroniques illuminators, part of which survives in the margins of the Valenciennes manuscript.

This libraire seems to have tailored his repertoire to the needs of his patrons. Individual images from these books may be identical, but their cycles are not. The manuscript in Baltimore, a fragment containing the second half of the chronicle,

contains miniatures at the beginning of each book that are as wide as a single column of text. The chronicle in Paris is complete, and its cycle follows a standard pattern with a four-part frontispiece and a single picture at major book divisions. The only deviation occurs within the first book of the chronicle, where a double miniature marks the chapter describing Clovis's baptism. The Grandes Chroniques in Valenciennes is the most elaborate cycle of this group. Its decoration includes two four-part miniatures and a two-column-wide miniature of early Merovingian rulers; it omits several miniatures from the reigns of the last Capetians that appear in the other two chronicles. The pattern of addition and omission in the Valenciennes chronicle places special emphasis on the lives of the early Merovingians and singles out Clovis, the first Christian king of France.

Although this unusual emphasis on Merovingian kings is difficult to explain, the emphasis on Clovis can be understood as a manifestation of the religion royale .[10] Exceptional miniatures in the manuscripts in Paris and Valenciennes illustrate events from Clovis's life. A double picture in the Grandes Chroniques in Paris shows Clovis's battle with the Alemanni and his baptism by Saint Remi (fol.

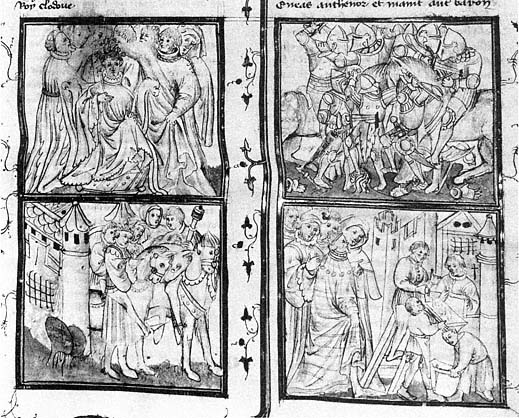

Figure 98

Baptism of Clovis; Clovis and Clotilda enthroned in the palace; Battle; Clodomir supervises the

execution of Sigismund, King of Burgundy(?). Grandes Chroniques de France . Valenciennes,

Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 637, fol. 14v. Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Valenciennes.

12v). Clovis is even more important in the book in Valenciennes; there the battle and baptism scenes are separated from their texts and combined to form a second frontispiece with pictures of Clovis and Clotilda enthroned and of Clovis's son, King Clodomir, supervising the execution of King Sigismund of Burgundy (Fig. 98). This new frontispiece to Book II of the Grandes Chroniques blends narratives from Book I and Book II to present an image of the founding and early years of the Christian kingdom of France. It thus constitutes a visual counterpart to the traditional frontispiece in the manuscript, showing the founding of France by Trojan refugees and the early years of the pagan kings of France (Fig. 99).[11]

Clovis's status in the Paris and Valenciennes manuscripts reveals the strength and broad appeal of the religion royale at the turn of the century and emphasizes the importance of Clovis to its dissemination. Although Clovis had been revered as the model of a warrior king as early as 1300, he was more renowned as a model of good and just kingship and as a saint by the late fourteenth century. With the active encouragement of Charles V, Clovis's cult began to flourish. It was most popular during the reign of Charles V's grandson, Charles VII. Histories, poems,

Figure 99

Coronation of Pharamond; Battle between French and Romans; King leaves city in formal

procession; King supervises the construction of Sicambria. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Valenciennes, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 637, fol. 2.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Valenciennes.

and sermons written in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries promoted the first Christian king, the prototype of the rex christianissimus , as an intercessor.[12] Clovis's universal appeal is one reason that such images decorate the copies of the Grandes Chroniques at Valenciennes and Paris.

Besides embodying popular royalist sentiment, Clovis's prominence in the Valenciennes chronicle demonstrates the lack of dynastic focus in the popular versions of the Grandes Chroniques , perhaps the central difference between the illustrations of royal and popular copies of the text. Beginning in the reign of Charles V, pictures in royal copies of the chronicle most frequently stressed the lives of Charlemagne and Louis IX, two saints from whom the Valois proudly claimed descent. Clovis and other Merovingian kings were rarely featured in the dynastic programs of royal manuscripts of the Grandes Chroniques or, for that matter, in arguments asserting the legitimacy of the Valois line. For instance, when dynastic arguments are marshaled in Le songe du vergier to prove that France was established "according to God and the Holy Scriptures," the account begins with Pepin. Although the Songe mentions the holy unction, it attempts to prove legitimacy by the sanctity of the Valois kings' Carolingian and Capetian ancestors; thus it omits Clovis.[13]

For the Valois kings of the late fourteenth century, Clovis's significance lay predominantly in the fact that the holy unction, which first appeared at his baptism and which signaled divine sanction for his reign, was used at the coronations of later French kings, including the Valois monarchs. Thus in royal texts written at the time of Charles V references to Clovis are confined almost exclusively to discussions of the sacred symbols of French monarchy, as for instance in the preface to the translation of Augustine's City of God or in Jean Golein's Traité du sacre .[14]

Conversely, such popular commissions as the Grandes Chroniques in Valenciennes sought to glorify French kingship rather than justify Valois legitimacy. As a result, they broke from the royal dynastic tradition and focused special pictorial attention on Clovis as the first of the long line of Christian kings of France.

Image not available

Plate 1

Coronation of Pharamond. Grandes Chroniques de France . British

Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 3. By permission of the British Library.

Image not available

Plate 2

Pagan and Christian kings of France. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque

Royale, Ms. 5, fol. 1. Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

Image not available

Plate 3

Battle of Courtrai. Grandes Chroniques de France . Castres, Bibliothèque

Municipale, fol 353v. Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Castres.

Image not available

Plate 4

Peers support the crowns of Charles V and Jeanne of Bourbon. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 439. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Image not available

Plate 5

Peers support the crown of Charles V. Coronation Book . British Library,

Cotton Tiberius B VIII, fol. 59v. By permission of the British Library.

Image not available

Plate 6

Peers support the crown of Jeanne of Bourbon. Coronation Book . British

Library, Cotton Tiberius B VIII, fol. 70. By permission of the British Library.

Image not available

Plate 7

Trojan fugitives at sea (Helenos, Aeneas, and Antenor?); Presentation of book to Charles

VI. Grandes Chroniques de France . Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 536, fol. 2. ©The Pierpont

Morgan Library 1991.

Image not available

Plate 8

Abduction of Helen; Punishment of Troy; Flight of the Trojans; Presentation

of book to Charles VI. Grandes Chroniques de France . Berlin, Deutsche Staatsbibliotek,

Phill. 1917, fol. 1. Photograph: Deutsche Staatsbibliotek Berlin.

Chapter Ten—

Advice to the Nobility in Manuscripts Produced in the Style of the Master of the Cité des Dames

A second group of manuscripts, painted for the nobility and members of the court in the style of the Master of the Cité des Dames[1] during the early fifteenth century, are noteworthy for their response to contemporary events rather than any generalized ties to the religion royale . Their designers seem to have taken the admonition of the prologue to heart; in a pictorial program tied strongly to the complex and unsettled history of early fifteenth-century France, they guide the reader to "find good and evil, the beautiful and ugly, sense and folly, and to profit from all [this] through the example of history."[2]

The Master of the Cité des Dames popularized a new mode of courtly illustration during the latter part of the reign of Charles VI. One reason for his popularity in courtly circles was probably his realistic style; he could evoke the interiors where the courtiers lived and the clothing and political emblems that they loved to wear,[3] yet he could also strip settings and costumes to their essential elements if that was more appropriate to the cycle.

Books produced by the Master of the Cité des Dames are an ideal source for exploring the kind of political guidance given to the nobility during the period of the French civil war. Four cycles by this artist survive, dating approximately from 1405 to 1415: Mazarine 2028, c. 1405–08; Phillipps 1917, c. 1409–10/15; M. 536, c. 1410–12; and B.R. 3, c. 1410–15.[4] The number of cycles in this style makes it relatively easy to screen out stock workshop scenes and concentrate instead on pictures that were specially tailored for one or more of these manuscripts. Analyzed in this way, the pictures clearly offer varied but timely advice to those charged with ensuring stable government in France—advice similar to that written by partisans of the political parties and by moderates like Christine de Pizan and Jean Gerson.

Manuscripts produced for the court by the Master of the Cité des Dames diverge from the pattern of illustration in such royal copies as Philip III's, John the Good's, or Charles V's, whose carefully coordinated pictures and texts together convey a political message. They differ too from courtly commissions whose pictures bear a looser relationship to their text and work to reinforce general royalist or universal themes in the chronicle. In the new mode, important political commentary appears in manuscripts made for the princes of the blood or for their supporters.

In the most sophisticated of these books, exemplified here by a chronicle in New York (M. 536), the text is edited to emphasize Burgundian interests, and the pictures form a tightly woven cycle that provides an independent counterpoint to the text. This appropriation of an illustrational mode hitherto restricted to royal copies of the chronicle provides an interesting parallel to political developments in France, where the queen and the princes of the blood were increasingly involved in royal government (and thus in the kind of history traditionally recorded in the Grandes Chroniques ) and where writers independent of the court sought to preserve the monarchy.

The Grandes Chroniques now in Berlin (Phillipps 1917) differs radically from that in New York. Its text is conventional, and its illustrations incorporate fifteenth-century political devices and emblems into historical images to provide a commentary on the present. This method of glossing illustration to make a political statement is only as sophisticated as the editor of the book chooses to make it.[5]

Not all the manuscripts painted by the Master of the Cité des Dames are illustrated in such innovative ways. Some, like the manuscripts in Paris (Mazarine 2028) and Brussels (B.R. 3), have more in common with courtly books from earlier periods. They contain some illustrations whose unusual subject matter relates to contemporary politics, but even these show the concern with preserving the monarchy that characterizes political literature of the early fifteenth century.

The Role of the Princes of the Blood

The Grandes Chroniques of circa 1410–12 in New York (M. 356) has the most secure connections with one of the two partisan groups, the Burgundian and the Orléanist parties, as textual evidence demonstrates. Although this Grandes Chroniques has no ex libris and is not listed in any surviving inventory from royal or ducal collections, certain textual peculiarities find their closest analogies in an unillustrated copy of the chronicle (B.R. 4) that belonged to Philip the Bold of Burgundy and remained in the Burgundian library after his death in 1404.[6] Both the illustrated chronicle in New York and the unillustrated one in Brussels incorporate a Latin poem at the end of Saint Louis's life that occurs elsewhere only in royal copies of the chronicle. Further, both extend the Grandes Chroniques past its usual ending by appending a continuation of Guillaume de Nangis. In this pair of manuscripts alone, the chronicle ends with a description of the death in 1384 of the count of Flanders, the Burgundian dukes' predecessor as ruler of Flanders. Finally, both these books and no others condense the description of one of the most important royal events of the late fourteenth century—the visit of the Holy Roman Emperor to Charles VI's father, Charles V—from 12 chapters to 20 lines of text.[7]

Although the manuscript from Berlin (Phillipps 1917) contains the standard version of the text of the Grandes Chroniques , its provenance suggests that it too was made in a Burgundian milieu. Arms added to the initial on folio 1 are those of a member of the Rolin family, which was active in Burgundian service. The most prominent member of this family, Nicholas Rolin, was employed by Philip the Bold; entered the service of Philip's son, John the Fearless, in 1408, working as counsellor, lawyer, and maître des requêtes ; and became chancellor of Burgundy under John's son, Philip the Good, in 1422.[8]

The pictures in these Burgundian Grandes Chroniques emphasize the governmental role of the French dukes—Charles VI's brother and uncles—and stress dynastic themes. These concerns are most evident in the frontispiece shared by M. 536 and Phillipps 1917 and in the distinctive form in which both manuscripts represent coronations. It is striking, then, that while pictures may convey parallel messages in these chronicles, they do so through two distinct modes of illustration.

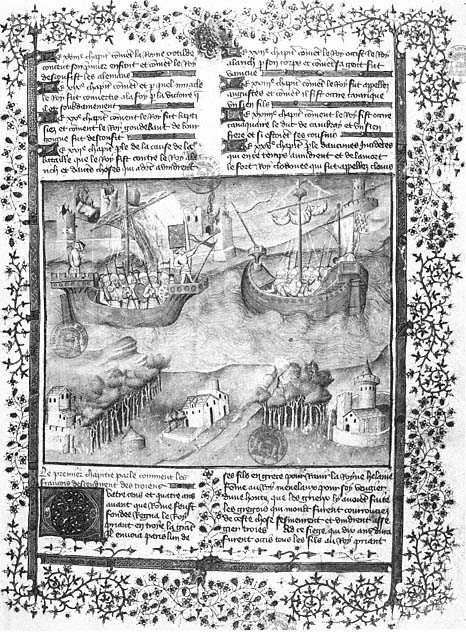

Most frequently, frontispieces to the Grandes Chroniques portray stories from the fall of Troy and the foundation by Trojan refugees of the kingdom that later became France. Visual solutions to the problem of illustrating these stories vary even in the oeuvre[*] of the Cité des Dames shop. For instance, the frontispiece (Fig. 100) from a copy of the Grandes Chroniques in Paris, which will be discussed in more detail later, concentrates exclusively on the flight from Troy. Frontispieces from M. 536 (Plate 7) and Phillipps 1917 (Plate 8) break from this tradition by making allusions that have no textual basis but are decidedly biased toward the Burgundian party. Both frontispieces contain three scenes from the Trojan story that at first glance seem identical but are not. In Phillipps 1917 the abduction of Helen and the punishment of Troy are in the upper register. At the lower left the flight of Aeneas to Rome represents the survivors of Troy who scatter all over the earth. In contrast, the frontispiece in M. 536 concentrates exclusively on the aftermath of the destruction. It makes no reference to the abduction of Helen and does not represent the destruction of the city. Instead it shows a diverse group of fugitives at sea (Helenos, Aeneas, and Antenor?), ranging from a king and queen to members of the nobility and soldiers.

The fourth frames jump forward in time to show the presentation of a manuscript to Charles VI, an event with no textual basis. By juxtaposing the reigning king with scenes from Trojan history, these pictures promote the Trojan origin of the French line, which was accepted throughout the fifteenth century.[9] Further, since the text of the chronicle describes the exploits of French rulers in an unbroken chain stretching from Priam of Troy to Charles VI, these frontispieces introduce the whole book by giving visual form to the beginning and the end of this chain.

It is unlikely that either of these manuscripts was destined for Charles VI, even though they show him enthroned in the frontispiece. Indeed, in both images (Figs. 101 and 102) Charles is shown nostalgically, sitting on a throne under a canopy decorated in red, green, and white, the emblematic colors that Charles bore until 1392, the year his madness struck.[10] By the time these two manuscripts were made, Charles VI's colors were white, green, red, gold, and black, the colors represented in such presentation scenes as the frontispiece to the Dialogues of Pierre Salmon , a manuscript presented to Charles VI in 1411. Thus, instead of being shown in these Grandes Chroniques as he was in 1410–12, the approximate date for these manuscripts, Charles VI is shown as he was before his illness became debilitating, during the golden period of his reign.[11]

Although these frontispieces derive from the same iconographic source, their iconography is used in very different ways. As we will see later, Phillipps 1917 further glosses the frontispiece and miniatures through the manuscript by including political devices. Perhaps because the text is more conventional in this book, its pictures had to carry the full weight of its message. On the other hand, the designer of M. 536, with its Burgundian version of the text, stripped scenes of all

Figure 100

Flight from Troy. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Mazarine, Ms. 2028,

fol. 2. Photograph: Bibliothèque Mazarine, Paris.

Figure 101

Presentation of book to Charles VI. Grandes Chroniques

de France . Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 536, fol. 2.

Photograph courtesy of the Pierpont Morgan Library.

Figure 102

Presentation of book to Charles VI. Grandes Chroniques

de France . Berlin, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, Phill. 1917,

fol. 1. Photograph: Deutsche Staatsbibliothek Berlin.

Figure 103

Coronation of Charlemagne. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 536, fol. 83v.

Photograph courtesy of the Pierpont Morgan Library.

devices and emblems and relied instead on the cumulative effect of the whole cycle to convey its pictorial message.

In M. 536 broad themes organize the pictures. The reader is not led to recognize themes and interpretations of history by the nonverbal yet explicit use of emblems or devices. Instead his perception is formed subtly by an insistent repetition of subjects and, in a few miniatures, by the use of something as understated as a particularly striking background motif. In this way M. 536 promotes its timely theme—the return of France to good government—and presents the French dukes as the agents who will accomplish this feat.

Two miniatures in M. 536, central to the content of the program, are the coronation of Charlemagne by Pope Leo (Fig. 103) and the coronation of Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile (Fig. 104). Charlemagne's coronation is a standardized scene, identical iconographically to that in Phillips 1917 (Fig. 105). The most innovative feature of the version in the Morgan Library is its background, where an elaborate checkerboard pattern is formed by blue lozenges, each containing a tiny fleur-de-lis. Although variations on this pattern were common in French book illumination in the fifteenth century, it is rare in this manuscript; its only other occurrence is in the miniature illustrating the coronation of Louis VIII.[12] This visual

Figure 104

Coronation of Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 536,

fol. 224. Photograph courtesy of the Pierpont Morgan

Library.

Figure 105

Coronation of Charlemagne. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Berlin, Deutsche

Staatsbibliothek, Phill. 1917, fol. 114.

Photograph: Deutsche Staatsbibliothek

Berlin.

Figure 106

Coronation of Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Mazarine, Ms. 2028, fol.

263. Photograph by the author.

connection between Charlemagne and Louis VIII reinforces a textual connection recorded in the life of Louis VIII, which includes the reditus regni ad stirpem Karoli Magni , the prophecy that the line of Charlemagne would return to power in France seven generations after the usurpation of power by Hugh Capet. Louis VIII was descended from Charlemagne on both his mother's and his father's sides and thus fulfilled the prophecy.

In M. 536 the miniature showing the coronation of Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile reinforces this dynastic theme by departing from the workshop's stock patterns, exemplified by Louis VIII's coronation from the Grandes Chroniques in Paris (Fig. 106). In the stock scene the clergy alone perform the coronation, but in M. 536 King John of Jerusalem and a duke have prominent places in the scene. Even though the presence of King John is noted in the text, he is rarely included in miniatures showing the event.[13] Thus the inclusion of these two figures in the miniature may convey the support or even, considering John's gesture, the blessing of the secular realm for the return of a ruler of Carolingian descent.

Beginning with the miniature illustrating the life of Louis VIII, the kinds of illustrations in M. 536 change. In the second portion of the book the lively narratives that characterize the illustration of Merovingian, Carolingian, and early

Figure 107

Coronation of Charles V and Jeanne of Bourbon. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 536, fol. 353v.

Photograph courtesy of the Pierpont Morgan Library.

Capetian history intermingle with distinctive coronations that prominently feature the dukes of France. Thus, in the coronations of Philip V, Charles V (Fig. 107), and Charles, VI, French dukes assume active roles as king-makers. The power of the ducal presence intensifies with each repetition of the basic composition in a cumulative and deliberate effect. The stress on dukes in coronations in this manuscript differs from that given the same scenes in the Parisian copy of the Grandes Chroniques (Fig. 108) where, for instance, the illustration of Charles V's coronation, like that of Louis VIII, emphasizes the agency of the clergy. Miniatures in M. 536 differ from those in the Brussels manuscript, where, instead of a coronation, a picture like that introducing the life of Charles V (Fig. 109) emphasizes both the king's power and a moment of Burgundian history in which Charles invested his brother, Philip the Bold, with the duchy of Burgundy.

The Burgundian manuscript in the Morgan Library may have a partisan text, but its pictorial message is moderate, claiming only that the dukes have a role in governing France. Pictures in Phillipps 1917 convey a similar message but are more biased. This manuscript, executed in the first decade of the fifteenth century, predates Louis of Guyenne's assumption of power and contains pictures glossed with references to the Burgundian-Orléanist conflict that take a decidedly Burgundian stance.

Figure 108

Coronation of Charles V and Jeanne of Bourbon. Grandes Chroniques

de France . Bibliothèque Mazarine, Ms. 2028, fol. 427v.

Photograph by the author.

Figure 109

Charles invests Philip the Bold with the

duchy of Burgundy. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque

Royale, Ms. 3, fol. 414v. Copyright

Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

The difference between the Burgundian chronicles in New York and Berlin is most clear in the frontispiece. In the frontispiece of M. 536, history and current events are separated; Charles VI takes his place in the fourth frame, and the Trojan story fills the other three frames. Images in Phillipps 1917 do not preserve this distinction of eras. Rather the fifteenth-century emblems and devices introduced in three of the four frames overtly merge different historical periods and refer explicitly to other members of the royal family. The designer is thus able to gloss history without changing the text.

Only one of the scenes in the frontispiece to the Phillipps manuscript is set totally in the early fifteenth century. In the fourth frame of the frontispiece (Fig. 102), the counsellor who stands next to Charles VI is John the Fearless, Charles VI's cousin, who became duke of Burgundy in 1404. John carries a hammer comparable to those he holds in other portraits dating from the first two decades of the fifteenth century.[14] At the same time, details in the Trojan story portrayed in the other frames gloss John's political opponent negatively. In the first frame of the same frontispiece (Fig. 110) Paris's gold collar of mail equates him with Louis of Orléans, Charles VI's brother and John's political rival who was assassinated in 1409. This is a simplified version of the collar of the Order of the Porcupine, which appears in greater detail in a portrait of Louis (Fig. 111) from Christine de Pizan's collected works in London, a contemporary manuscript painted by the same artists.[15] The Order of the Porcupine, sometimes called the Order of the Mail, was founded in 1393 by Louis of Orléans, who often wore the collar with or without its dangling porcupine. Thus Louis of Orléans is identified with Paris, whose passion for Helen of Troy started the Trojan war.

Additional details in the frontispiece may reinforce this negative interpretation. The second frame (Fig. 112) portrays the Greek king Menelaeus who, like John the Fearless, does not appear in M. 536 (Plate 7). Even though his presence is justified by the text of the chronicle, Menelaeus evokes the French king because he wears a blue robe decorated with gold—the heraldic colors, if not the precise emblems, of France. These details of costume added to the pair of miniatures in the upper register provide an extratextual commentary suggesting that, just as Paris stole Helen from King Menelaeus, Louis of Orléans stole Isabeau from Charles VI. If such a reading of the frontispiece was intended, this could be one of the first images to refer to the rumor widely disseminated in Burgundian literature of the 1420S that Louis of Orléans and his sister-in-law, Isabeau of Bavaria, had an illicit relationship.[16]

The differences between the New York and Berlin frontispieces demonstrate the flexibility of the Master of the Cité des Dames's mode of glossing. By adding a few details, he could transform a politically neutral image like the frontispiece to M. 536 into a polemical one. Other emblematic elaborations in Phillipps 1917 reinforce the role of the duke of Burgundy as an especially trusted assistant to King Charles VI. For instance, in the image of the coronation of Charlemagne as emperor (Fig. 105), both the pope and a spectator wear emblems that were popular in the early fifteenth century. The pope's robe is sprinkled with blazing suns that evoke the arms of Pope Alexander V (1409–10), who was supported by the French and elected to end the schism; the most prominent spectator to the left wears a robe covered with schematic planes, emblems of John the Fearless.[17] No complex message is hidden in this scene; rather, the reference to Alexander V situates the

Figure 110

Abduction of Helen. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Berlin, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, Phill. 1917,

fol. 1. Photograph: Deutsche Staatsbibliothek Berlin.

Figure 111

Christine presents her book to Louis of

Orléans. Christine de Pizan, L'Épistre

Othéa . British Library, Harley 4431, fol.

95. By permission of the British Library.

Figure 112

Punishment of Troy. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Berlin, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, Phill. 1917,

fol. 1. Photograph: Deutsche Staatsbibliothek Berlin.

pictorial gloss in the present, after 1409 when Alexander took office, and the portrayal of John the Fearless assisting at Charlemagne's coronation reiterates the message of the frontispiece—John's loyalty to Charlemagne's namesake, Charles VI.[18]

Phillipps 1917 shares with M. 536 the innovative representation of coronations in which the dukes take an active role. Their basic pictorial vocabulary can be seen, for instance, in representations of the coronation of Charles V and Jeanne of Bourbon (Figs. 107 and 113). Dukes wearing circlets of gold are prominent in each image, and the message—that the dukes contribute significantly to making a king—is clear, particularly when this type of coronation is compared to the Master of the Cité des Dames' s stock scene (Fig. 108).

Although the form and content of individual coronation pictures may be identical in M. 536 and Phillipps 1917, their function in the program of miniatures is not. The Morgan Library's Grandes Chroniques uses such scenes sparingly. The first royal coronation, at the life of Louis VIII, appears within the framework of the reditus , and subsequent scenes of royal coronation (at the lives of Philip V, Charles V, and Charles VI) were doubtless intended to recall that dynastic structure by echoing its compositional type. Coronations in Phillipps 1917 are not so tightly woven into a dynastic framework; rather they are unified by the concept of the Christian kingship of France.

This theme, which found broad popularity in the fifteenth century through the religion royale , is initiated by the first coronation scene in this manuscript, the coronation of Clovis (Fig. 114). Most of the following coronation sequences assume this form, but the coronations of Saint Louis (Fig. 115) and Louis IV (Fig. 116) are more complex compositions. The importance given Louis IX's coronation

Figure 113

Coronation of Charles V and Jeanne of Bourbon. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Berlin, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek,

Phill. 1917, fol. 484. Photograph: Deutsche Staatsbibliothek Berlin.

Figure 114

Coronation of Clovis. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Berlin, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, Phill.

1917, fol. 7v.

Photograph: Deutsche Staatsbibliothek Berlin.

Figure 115

Coronation of Louis IX. Grandes Chroniques

de France . Berlin, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek,

Phill. 1917, fol. 308v.

Photograph: Deutsche Staatsbibliothek Berlin.

Figure 116

Coronation of Louis IV. Grandes Chroniques de France . Berlin,

Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, Phill. 1917, fol. 199.

Photograph: Deutsche Staatsbibliothek Berlin.

through Louis's halo and the elaborate dress of the attending dukes makes sense both within the context of Christian kingship that governed the form of coronations in this book and within the broader context of devotion to Saint Louis at the French court. Louis's sainthood confirmed the Christian kingship of France that Clovis had initiated, and, as we have seen, Capetian and Valois kings descended from Louis were quick to promote his sanctity.

Louis IV's coronation is the second to represent barons in distinctive costumes. This picture does not celebrate Christian kingship so much as the role of the barons in ensuring continuity. It commemorates the return of the legitimate king to the throne by the barons of France, who brought the young Louis IV back to France after his mother had fled with him to England. Like the distinctive coronation type that occurs throughout M. 536 and Phillipps 1917, this image concentrates on the support of the barons for the monarchy and their action on its behalf. It is tempting to see this image as a reference to a contemporary event in French history. In 1405 John the Fearless and his supporters brought the dauphin back to Paris when his mother, Isabeau of Bavaria, and his uncle, Louis of Orléans, sought to remove him from the capital and free him from Burgundian control.

The frontispiece, the illustration of Charlemagne's coronation, and the generalized representations of coronation demonstrate how pictures in this specific chronicle work as contemporary glosses to establish independent parallels between French history and events from the time of Charles VI. The pro-Burgundian, anti-Orléanist message of this manuscript is cumulative, as in M. 536, but it operates on a simpler level. The pictures and text of M. 536 are so closely interwoven that the message of its pictorial program depends upon a consideration of all its parts. In Phillipps 1917, however, the accumulation of information from a sequence of images may refine the political message, but each individual image contains enough information to convey its message independently.

What is most striking about these two copies of the Grandes Chroniques is that, no matter how the message is conveyed, the underlying call for ducal or baronial responsibility is pervasive. This emphasis on noble support for the king had more parallels in contemporary royalist political writings than in pictorial cycles illustrating previous Grandes Chroniques .

Such authors as Christine de Pizan and Jean Gerson realized the dukes' powers and exhorted them to work for the good of the monarchy. Christine dedicated her works first to Philip the Bold, duke of Burgundy; then to Louis, duke of Orléans; and finally to John, duke of Berry, reflecting her changing opinions about who would be best equipped to govern the realm as custodian for the young dauphin during Charles VI's madness. In times of crisis, Christine and Gerson directly addressed the dukes to encourage them to place the French realm above their own ambitions. After the aborted kidnapping of the dauphin Louis by Louis of Orléans in 1405, Christine's Lettre à la reine and Gerson's sermon, Vivat rex , called for peace and emphasized the importance and the responsibilities of the king and his counsellors, a theme to which Gerson returned again in the sermon, Veniat pax of 1408, and which Christine addressed in Lamentacion sur les maux de la guerre civile in 1410.[19] These texts, like the pictures in the Morgan Library's Grandes Chroniques , expressed the hope current in the first decades of the fifteenth century that the dukes of France would responsibly safeguard the French monarchy rather than expand their own power.

The insistent presence of the dukes in the Grandes Chroniques also mirrors political reality. When these manuscripts were painted, the princes of the blood were actively involved in the government of France, and Burgundian power seemed to be at its strongest. By the end of December 1409, John the Fearless had become sole guardian of Louis of Guyenne and was thus in a position to influence the dauphin, the virtual ruler of France, during Charles VI's attacks.[20] John shared the regency briefly with the duke of Berry in 1410, but by the end of the civil war in 1412, John the Fearless was in a strong position in the government and at the height of his power.

The Role of the Queen and the Dauphin

Equally concerned with contemporary problems, other manuscripts of the chronicle painted by the Master of the Cité des Dames focus on the queen and the dauphin rather than the dukes. The pictures in a Grandes Chroniques now in Paris (Mazarine 2028), which predates the assassination of Louis of Orléans in 1407, provide nonpartisan commentary on the conflict between Louis of Orléans and John the Fearless and the importance of Queen Isabeau of Bavaria's role in politics. A second chronicle, in Brussels (B.R. Ms. 3), dates from the second decade of the fifteenth century when the dauphin, Louis of Guyenne, approached his maturity; some of its images refer to the importance of his education. Together these books address additional issues of concern to the court and to Parisian intellectual circles in the first part of the fifteenth century. Like the chronicles in Berlin and New York, they could be termed royalist books. They support those who sought to preserve the French monarchy but concentrate on different agents of preservation.

An imposing frontispiece and three rare subjects gloss French history with contemporary commentary in the Grandes Chroniques from the Bibliothèque Mazarine. As in Phillipps 1917, pictures in this chronicle include arms and devices that identify figures from French history with contemporary personages. They celebrate the French dynasty and comment on the civil war in France.

The Trojan frontispiece (Fig. 100) embodies a dynastic theme. Within this miniature, two boats fleeing the burning city of Troy display the arms of France and Brittany. This juxtaposition is perplexing at first, because the text of the chapter describes the refugees from Troy but does not mention the Bretons. Instead, the chronicle notes three major countries founded by Trojan refugees: Italy, founded by Aeneas; Britain, by Brut; and France, by Francion.

This use of Breton arms becomes clear when we consider the source for the description of Brut's life in the Grandes Chroniques , Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain .[21] Geoffrey's text stresses the interrelated histories of Britain and Brittany, which was colonized by the descendants of Brut. When Britain was in difficulty, the Bretons sent armies to aid their island relatives. War, pestilence, and famine, however, eventually defeated the Britons, who emigrated as a nation to Brittany. Thus, as Geoffrey of Monmouth describes it, "From that time, the power of the Britons ceased in the island, and the Angles began their reign."[22] Although the Grandes Chroniques never refers explicitly to the history of Brittany, it does echo Geoffrey: "From this Brut descended all the kings who were in the land [Britain] up until the time when the English, who came from one of

Figure 117

Queen Clotilda divides the realm among her sons. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Mazarine, Ms. 2028, fol. 14. Photograph by the author.

the countries of Saxony called Angle, took the land for which [reason] it is called England."[23] We could say, then, that the Trojan refugees in this miniature bear Breton arms because the Bretons, rather than their English supplanters, were of Trojan descent.

Contemporary history provides another motive for the use of Breton arms. In 1396, Jeanne of France, third daughter of Charles VI and Isabeau of Bavaria, married John of Montfort, heir to the duchy of Brittany.[24] The alliance of these two houses was politically motivated. Notoriously independent, Breton dukes placed the security of their duchy before their duties as vassals of the French king. By securing a marriage tie with the Breton house, the French sought to strengthen relations between the Bretons and the French. The heraldic display in the frontispiece thus implies that the recent connection of the two houses has its roots in their shared Trojan ancestry.

Other pictures in the chronicle refer to internal French politics. For example, the illustration to the second book (Fig. 117) shows Queen Clotilda dividing the realm among her four sons, pictured as kings. Two of these kings have special attributes: the king at the far right clasps a stick, and the king at the far left holds a schematized hammer. These are generalized references to the political emblems of Charles VI's brother and cousin—the bâton noueux or knotty stick of Louis,

Figure 118

Queen Clotilda divides the realm among her sons. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Berlin, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek,

Phill. 1917, fol. 14. Photograph: Deutsche Staatsbibliothek Berlin.

duke of Orléans, and the hammer of John the Fearless, duke of Burgundy.[25] The history of Queen Clotilda's sons clarifies the references to these noble cousins.[26] After Clotilda partitioned the realm, two of her sons formed a greedy alliance to battle one of their brothers. Only Queen Clotilda's active intervention prevented fratricide. The use of Burgundian and Orléanist emblems in a scene of Clotilda and her sons may therefore comment on the deadly rivalry between these blood relations of Charles VI.

The timeliness of this image is confirmed by representations in the two later manuscripts of the Master of the Cité des Dames , neither of which includes the simplified hammer. In the pro-Burgundian manuscript, Phillipps 1917, for example (Fig. 118), Clotilda's son at the far left is the only one to retain his emblem. Without the opposing hammer, the baton loses its overlay of political meaning and serves as a neutral sign of office.[27]

The inclusion of Clotilda with her sons may also address a second theme that permeated royalist, as opposed to Burgundian or Orléanist, political writings of the early fifteenth century—the importance of the queen in governing the realm. Certainly the theme of queenly power is expressed in two other pictures from the Paris manuscript: the coronation of Charlemagne's son, Louis the Pious, as King of Aquitaine (Fig. 119) and the discussion of the royal succession after the death

Figure 119

Coronation of Louis the Pious as king of Aquitaine.

Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque

Mazarine, Ms. 2028, fol. 131. Photograph by the author.

of the last Capetian king (Fig. 120). Never before had queens been included in these scenes. The second in particular shows the queen, an expectant mother, as an important protagonist in discussions about the future government of France. Probably because of the short lives of French dauphins (three had died by 1397), the image recalls an important theme in contemporary politics and literature—Queen Isabeau of Bavaria's role in the government of France and the hope that she would interfere to regulate the chaos caused by the rivalry of the dukes.

The major source of Isabeau's power was her role as one of the regents charged with the tutelle , or education, of the dauphin in case the king should die or be absent from the realm.[28] Charles V had been the first king since Saint Louis to give such a prominent role to the queen. His laws were adopted by Charles VI and his council in 1393—right after Charles's first attack of insanity—and remained in effect until 1407.[29] Under their provisions, Louis of Orléans became regent if the king died or was "absent," and Isabeau of Bavaria and the dukes of Burgundy and Berry were charged with the education of the prince. As royalist writers like Christine de Pizan recognized, Isabeau's role as guardian of the dauphin and peacemaker in a regency government became especially important once the dukes of Burgundy and Orléans became openly hostile in 1405.[30]

Figure 120

Discussion of the royal succession. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Mazarine, Ms. 2028, fol. 354v. Photograph by the author.

The close relationship between royalist sentiment and pictorial imagery in the Grandes Chroniques in Paris continues in later chronicles by artists from the Cité des Dames workshop. The Grandes Chroniques in Brussels (B.R. 3) dates from the second decade of the fifteenth century when Charles VI's heir, Louis of Guyenne, was in his early teens. Perhaps as a result of the dauphin's maturity, distinctive miniatures in this book focus exclusively on the importance of the education of dauphins.

Three pictures in this book show the interaction of a king and his son. One shows King John the Good, Charles VI's grandfather, investing his young son, Charles, with the Dauphiné (Fig. 121). Two others offer examples of good and bad kingship that were especially appropriate to a dauphin named Louis. The miniature beginning Louis the Stammerer's life (Fig. 122) shows Louis compromising himself to gain power; he gives the barons anything they want in order to win their favor. In the process, Louis grasps his son's wrist to compel him to participate. A complementary image from another section of the chronicle shows the prince's willing compliance when his father is a positive influence. In this picture from the beginning of the life of Saint Louis (Fig. 123), the young Louis sits next to his father, Louis VIII, and helps supervise the burning of heretics.

Figure 121

John the Good invests Charles with the Dauphiné.

Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Royale,

Ms. 3, fol. 373.

Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

Neither miniature faithfully reflects the chronicle's text.[31] Louis the Stammerer had two sons—Louis and Carloman—neither of whom was mentioned in the chapter that this picture illustrates. Further, Saint Louis did not take part in his father's persecution of heretics; his father was in the south of France and Louis was in Paris. By departing from the text in representing kings with heirs named Louis, the artist created compositional and thematic analogies. They were apt choices for exempla at the time when Charles VI's son, Louis of Guyenne, was dauphin.

Like the emphasis on queenship in the Grandes Chroniques now in Paris, the focus on the dauphin in B.R. 3 paralleled contemporary historical events and reflected concerns expressed in contemporary literature. The ordinance of 1407 empowering Louis of Guyenne to rule during his father's "absences" made the dauphin the most important person in the realm besides the king. His education was addressed by Christine de Pizan in several works and by Jean Gerson in a treatise sent to the tutor of the dauphin, Jean d'Arsonval, and dated between 1408 and 1414.[32] These writings discussed the religious, moral, and intellectual formation of the future king and frequently cited examples of past kings, most notably Louis of Guyenne's famous ancestor, Saint Louis, as models of government.

Figure 122

Louis the Stammerer and his son Louis accede to barons.

Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 3,

fol. 147v. Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

Manuscripts decorated by the Master of the Cité des Dames provide insights into a special kind of courtly reaction to the French civil war. Like the illustrations in royal manuscripts before them, these images of history form a private complement to more overt political writings, featuring images of the contemporary powers in France—the dukes and the queen—and representing themes like the role of the dukes in governing France, the Burgundian-Orléanist conflict, the importance of the queen as mediator and peacemaker, and the education of the dauphin. As in the political literature of the time, these images offer an important perspective on the political climate of fifteenth-century France.

The Master of the Cité des Dames used various methods of illustration to gloss the chronicle and express his political message. The simpler way is to elaborate an individual picture that, when read with its own text, comments on contemporary events. This sort of elaboration ranges from the inclusion of characters described in the text but rarely visualized (as in Jeanne of Evreux's presence at the discussion of the royal succession in Mazarine 2028), to the addition of historical characters who contradict their text (Saint Louis happily burning heretics in B.R. 3), to the insertion of anachronistic emblems and devices into stock scenes (as in the Burgundian hammer and the Orléanist Order of the Porcupine in the frontispiece

Figure 123

Louis VIII and his son Louis supervise the burning of heretics.

Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 3,

fol. 248. Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

of Phillipps 1917). In these glosses, immediately perceptible to a careful reader of one chapter or the whole manuscript, the overarching message of the program of decoration conveys the same message as each individual part.

The Master of the Cité des Dames' s more complicated method of glossing encompasses the whole program of decoration. In this system, most commonly seen in kings' books, individual pictures carry only a portion of the message. Images work in sequences, building a message through repeated compositions (as in the series of coronations in M. 536) or through visual cross-referencing (as in the pair of exempla for the education of the dauphin in B.R. 3). The message of the whole is much more than a sum of its parts—and often is very subtle, perhaps explaining why this kind of cycle occurs most frequently in manuscripts like that in New York where the text has been edited to promote a partisan view.

These manuscripts provide important evidence for a changing view of history in the fifteenth century. In the late fourteenth and the early fifteenth century the princes of the blood emerged simultaneously as major participants in government and as important patrons of the arts,[33] and during the reign of Charles VI the blood relations of the king began to assume a special status—to share, in a sense, some of the holiness of the French king, as they shared some of the responsibilities

of government. At this time, therefore, the decorative programs in the Grandes Chroniques worked to extend to the king's blood relations the prologue's directive that the king should seek models in its pages. The conviction, held by the princes of the blood and the court, that the blood relations of the king also had a mandate to govern inspired the creation of such advice books as the Grandes Chroniques decorated by the Master of the Cité des Dames .