Reproduction 2: The Work of Art as Limited Edition

My landscapes begin where da Vinci's end.

—Marcel Duchamp

The artistic questions raised by Fountain, as an object of mass production, are compounded by Duchamp's explicit use of art prints, reproductions that he "rectifies" with small alterations and signs as works of art. Starting with Pharmacy (Pharmacie; 1914), a commercial print of a winter landscape to which Duchamp adds "two little [red and green] lights in the background" (DMD , 47); followed by Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 3 , a photograph of his painting that is hand colored; culminating with L.H.O.O.Q., a reproduction of Leonardo's Mona Lisa to which Duchamp added a mustache and a goatee; and L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved (L.H.O.O.Q. rasée; 1965), a reproduction of the Mona Lisa pasted on an invitation card, there is a succession of reproductions—printed or photographic—that are re-presented as original works of art.

Moreover, beginning with the color plate reproduction of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box; 1934), followed by miniature facsimiles of the urinal (1938–58) and the full-scale versions (1950–64), one can sense Duchamp's deliberate effort to reproduce not only specific works but a sample of his entire artistic corpus, as in the case of The Box in a Valise (1941–68). Pierre Cabanne interprets Duchamp's reproduction of his own works as a sign of his desire to assemble and preserve them as a miniaturized and transportable corpus[27] This hypothesis, however, in no way accounts for Duchamp's systematic experimentation with the concept of artistic reproduction and the questions it poses regarding the "originality" of works of art. Unlike Walter Benjamin, who, in his essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" (1936), questions the impact of mechanical reproduction on the loss of "aura" of the work of art, Duchamp assumes mass reproduction as a given, as the most salient and pervasive manifestation of modernity.[28] The concept of mechanical reproduction becomes for Duchamp a new way of thinking about art, one that treats the "object" as

a series of "impressions," or multiples, in order to redefine the conceptual relation between art and nonart.

Pharmacy (fig. 52) is a commercial color print that Duchamp bought in an art supply store. The only appropriation (or, rather, rectification) that he carries out on this commercially reproduced image is the addition of two identically painted touches of color, red and yellow-green, in the form of three superimposed circles. Duchamp explains that the addition of these two colored lights "resembled a pharmacy" (DMD , 47).[29] Before examining this work in further detail, one must note the impact of Duchamp's recuperation of a commercially available color print, which is available alongside painting supplies in an art store. Is this work the equivalent of painting supplies? In other words, is there a relation between the mass fabricated tubes of paint and this commercial color print? In a talk "Apropos of 'Readymades'" (1961), Duchamp concludes: "Since the tubes of paint used by the artist are manufactured and readymade products, we must conclude that all the paintings in the world are 'ready-mades aided' and also works of assemblage" (WMD, 142). This comment sheds an indirect light on Pharmacy insofar as Duchamp establishes an equivalence between the materials of painting and prints as painterly materials. The fact that they are both mass-produced serves to redefine the nature of the art of painting into works that can be considered as either assisted or reassembled ready-mades.

The title Pharmacy further verifies the hypothesis that this work marks Duchamp's inquiry into the relation between the materials and the art of painting. In Leonardo's time the pigments and the media of painting could be sold only by the Guild of Doctors and Apothecaries.[30] This implicit allusion to Leonardo is not accidental, considering his use of the reproduction of Mona Lisa in L.H.O.O.Q. .[31] Thus, it seems that certain pigments were already made, even during the Renaissance when the artistic and artisanal aspects of painting were considered to be at their height. Duchamp's refusal of color and ultimate abandonment of painting was expressed in terms of his rejection of the visual seduction of painting, as "retinal euphoria" and the "easy splashing way," which entails an aversion to "the cult of the paint itself" and the "intoxication of turpentine." While deploying touches of color, Pharmacy represents an effort to problematize the fetishization with the materials of painting and thus alter the very medium

Fig. 52

Marcel Duchamp, Pharmacy (Pharmacie), 1914. Rectified

ready-made: commercial print of a winter landscape with

two sets of three vertical dots added in gouache, red

and green, alluding to the bottles in a pharmacy window,

10 1/4 x 7 5/8 in. Galleria Schwarz, Milan.

Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

of painting. It is perhaps not by accident that the conditions of production of Pharmacy on a train, in the half-darkness of dusk, recall Duchamp's earlier experiment in Portrait of Chess Players with painting by a green gaslight. This rejection of daylight is tied to his efforts to discover new tones in painting. "I wanted to see what the changing of colors would do. . . . It was an easy way of getting a lowering of tones, a grisaille" (DMD , 27). In the case of Pharmacy, however, the lowering or graying of tones (grisaille) is already part of the work, since this commercial color print reproduced by printed dots cannot have the brilliance of paint.

Why then does Duchamp add those two touches of red and green, which are, in fact, the only marks of "rectification" of this otherwise banal commercial print? Duchamp's designation of this work as a "Rectified Ready-Made" becomes clearer once we consider its meanings. The word "rectify" comes from the Latin (rectus, right and facere, to make). Its other meanings provide some interesting clues: 1) to correct the

faults in; remove mistakes from; set right; 2) to refine or purify, as liquids, by distillation; 3) to adjust correctly: in electricity, to change from alternating to direct, as an electric current; in mathematics, to find the length of (a curved line).[32] That these various meanings might inflect Pharmacy seems at first remote, if not downright farfetched. As a ready-made, however, Pharmacy seems to be an effort to rehabilitate painting from one of its fundamental conditions: the artisanal intervention of the artist. By analogy to an apothecary, Pharmacy emerges as that original site where the production of pigment, through grinding and distillation, becomes displaced through mass production. This image is rectified at dusk, in the absence of light, while two lights, red and green, are added to the image. The presence of these two lights playfully alludes to color blindness and/or the alternating colors of a semaphore (appropriate to a train or to headlights; a pun on the phares of Pharmacy ).[33] Through this pun, electricity becomes inscribed in the image in an inverted form, as alternating current, rather than direct current.

When asked by Cabanne if this work was an instance of "canned chance," Duchamp agreed, signaling an affiliation between Pharmacy and Three Standard Stoppages. In the latter, three threads one meter in length are dropped. Their curved outline is reproduced by being glued first to canvas, then to glass, and finally, by being reproduced as a wood template. This work thus "cans chance" by destroying the notion of a metric standard and by addressing the mathematical problem of finding the length of a curved line. Analogously, Pharmacy destroys the notion of an aesthetic standard by deploying points of color on a print. The mathematical intervention in this case remains invisible, as long as one does not consider the optical properties of this piece. In fact, as Ülf Linde and Jean Clair suggest, Pharmacy might be Duchamp's earliest experiment with anaglyphic vision, for if the spectator dons red and green glasses, these points coalesce, generating a figure in relief against the blurred background.[34] This stereoscopic effect is explored explicitly in another work, Hand Stereoscopy (1918–19), where two visual pyramids (such as we find in treatises on perspective) come to the foreground when viewed through these special glasses. A third dimension comes into view by its optical projection through color, thereby suggesting that these dots of pigment are the projection of the perspectival (mathematical) principles

underlying optics. This is why, according to Duchamp, "perspective resembles color" (WMD , 87).

This inscription of a potential figurative dimension into a set of colored dots captures the dilemma that confronted Georges Seurat when he did away with the brush in order to construct images from fields of colored dots. The act of viewing a Seurat painting involves a projection of the points of paint into actual figures. This dilemma is alluded to by Duchamp in an early note: "the possible is/ an infra-thin—/ The possibility of several/ tubes of color/ becoming a Seurat is/ the concrete 'explanation'/ of the possible as infra/ thin The possible implying/ the becoming—the passage from/ one to other takes place/ in the infra thin" (Notes, 1). In his interviews Duchamp describes Seurat as the "greatest scientific spirit of the nineteenth century" and as an "artisan" who nevertheless "did not let his hand bother his spirit."[35] As the embodiment of two divergent tendencies—art as a conceptual intervention (matière grise ) and art as an artisanal skill that relies on the hand (patte )—Seurat's work exemplifies the dilemma that painting poses for Duchamp.[36] This dilemma is reenacted in Pharmacy, to the extent that the presence of red and green dots inscribes an allusion to Seurat's pointillist technique, suggesting the possibility of the tubes of color "becoming a Seurat." At the same time, this implied passage (ready-made, in a sense) from paint to painting also introduces the possibility of conceptualizing this relation. The effort to tone down color (grisaille) diminishes color's material centrality to the art of painting by privileging the matière grise, in this context, literally the "gray matter," and the grayness of the commercial print. As a transitional object between paint and painting, Pharmacy rectifies the dominance of art through the repetitious logic of the ready-made. What appears initially as an act of reproduction now emerges in a new sense, as an act of production based on a new concept of materiality that combines the materials of painting with painting understood as conceptual material.

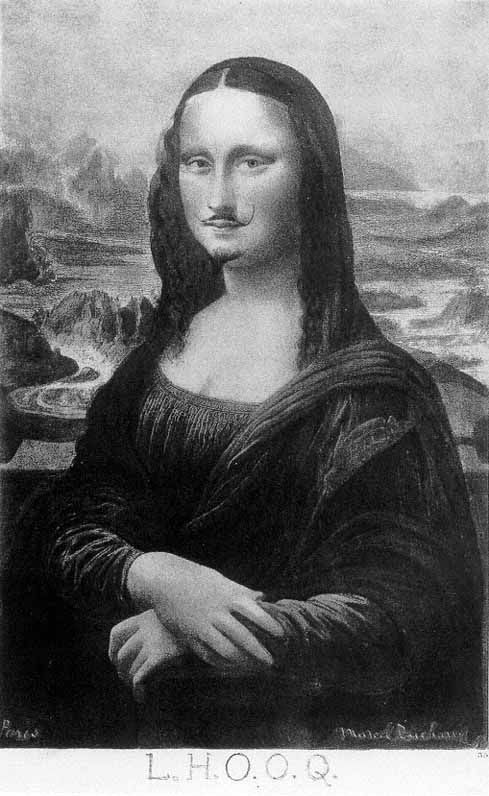

This gesture is repeated in a new way in L.H.O.O.Q. (fig. 53), Duchamp's infamous appropriation of Leonardo's Mona Lisa (which is also known as La Gioconda ). Instead of choosing an ordinary reproduction, Duchamp selected a work that is identified with all that is sacred and beautiful in art. By disfiguring this idealized image through the graffitilike addition of a mustache and a goatee, Duchamp attacks both the

Fig. 53

.Marcel Duchamp, replica of L.H.O.O.Q., 1919, from Box in a Valise (Boîte En Valise), 1941–42.

Rectified ready-made: reproduction of the Mona Lisa to which Duchamp has added a moustache

and beard in pencil, 7 3/4 x 4 7/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

painting's "aura" and its cult value in the history of art.[37] Walter Benjamin observes the danger that the work of art incurs in the age of mechanical reproduction:

That which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of a work of art . . . the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of the tradition. By making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence.[38]

For Benjamin, the "uniqueness of a work of art is inseparable from being embedded in the fabric of tradition." His statement affirms the cult value of art as defined by the "contextual integration of art in tradition."[39] By using a commercial print of a masterpiece, Duchamp does in fact remove it from the painterly tradition, since the plurality of the reproduction challenges the uniqueness and originality of the work. This gesture, however, merely reiterates the manner in which works of art are removed from their original location in order to be amassed under the institutional authority of the museum. The decontextualization that takes place through the reproduction of a work of art is but the extension of the decontextualization that the museum performs on works of art as it makes them readily accessible for viewing by a mass public.

As Benjamin points out, in the modern age the "exhibition value" of the work supersedes the "cult value" of art. Insofar as artistic production begins with ceremonial objects, the value of these objects is defined by their "existence, not their being on view."[40] The fact, however, that in a museum all objects are displayed equally tends already to destroy the specificity of particular works of art. As Duchamp observes, the act of viewing involves an interchange between the spectator and the work that is minimized by the conditions of display of the object:

The exchange between what one/ puts on view [the whole/setting up to put on view (all areas)]/ and the glacial regard of the public (which sees and/forgets immediately)/ Very often/ this exchange has the value/ of an infra thin separation/ (meaning that the more/ a thing is admired/ and looked at the less there is an inf. t./ sep). (Notes, 10)

In the context of the museum where everything is on display, the display determines the act of seeing. The regard of the public becomes "glacial," to the extent that admiration of a work of art supplants its visibility, obviating the conventions and criteria that define it.[41] The eyes of the spectator become "glazed," as "seeing" in this context means "forgetting." Public regard is conceived of in terms of an exchange whose value is described by Duchamp through the notion of the "infrathin," which he compares to an "allegory of forgetting" (Notes, 1). What is being forgotten in the popularization of art is the fact that value is neither acquired nor inherited; rather, value belongs to the possibility of an exchange between the spectator and the work.

By actively posing the question of popularization through the notion of reproduction, L.H.O.O.Q. reactivates the question of value and its relation to a work of art. This joke on the Gioconda emerges as a commentary on a punning reading of L.H.O.O.Q. as "LOOK," that is, the "infrathin" separation or interval inscribed into the gaze that constitutes the work.[42] The addition of the mustache and the goatee to this smiling and impassive image of the Mona Lisa exposes the fragility of the viewer's gaze, the ease with which this embodiment of feminine ideals can switch gender and thus inscribe a masculine dimension into the image. Although the title L.H.O.O.Q. can be read as the French slur, "she has a hot ass" (elle a chaud au cul ), this vulgar reference to feminine desire is undermined by the masculine "hair," or rather "air," of the image. This vulgarization of an image, whose impact relies on the lack of expression and an ambiguous smile, is due to a con joke on Gioconda, the falsification of its pictorial intent. Not only is the spectator conned by a reproduction but the potential androgyny of this figure suggests that the original itself may be a con job.

Leonardo's Mona Lisa is a portrait with no referent, because this image has never been definitively identified with a particular historical persona. Possible identifications vary, including people such as Isabella d'Este and the wife of a merchant named Giocondo, whose portrait was painted by Leonardo and whose name can be construed as a pun on playfulness (gioco, in Italian).[43] Although Isabella d'Este was known as a practical joker, a detail that might explain the peculiar turn of her smile, in the end there is no evidence clearly indicating the identity of the model of this enigmatic portrait.[44] In addition to the inconclusive nature of the paint-

ing's double title, recent computer studies suggest that this portrait might in fact be a self-portrait, inverted as if in a mirror.[45] Given Leonardo's penchant for inverting his handwriting by writing from right to left, a "mirrorical turn," it would not be surprising that this visual representation of himself might take such a turn. This act of optical transvestism inscribes a fundamental ambiguity into the image, an ambiguity that, ironically, has traditionally been interpreted as the ultimate sign of femininity: Mona Lisa (La Gioconda ) as la prima donna del mondo.

Duchamp's own playful joke on this portrait appears less as a gesture of desecration and violation than as the perpetuation of a long-standing artistic joke.[46] The discrete, delicately penciled-in mustache and goatee inscribe into the image the masculine referent that heretofore had disguised itself in the ambiguity of an optical illusion. The mustache and the goatee return this missing dimension to the image. As Duchamp observes: "The curious thing about that mustache and goatee is that when you look at it the Mona Lisa becomes a man. It is not a woman disguised as a man; it is a real man, and that was my discovery without realizing it at the time" (emphasis added).[47] The mustache and goatee function as a playful index both of Leonardo's "mirrorical turn" and of Duchamp's repetition and rectification of this gesture as a "mirrorical return."

In a work entitled Moustache and Beard of L.H.O.O.Q. (1941), which is a drawing made as a frontispiece for a poem by George Hugnet (1906–1974), entitled Marcel Duchamp (8 November 1939), the mustache and beard are presented by themselves, accompanied by Duchamp's signature. These two elements marking Duchamp's appropriation of Leonardo's Mona Lisa and functioning as his visual signature become decontextualized and reassembled, as it were, under Duchamp's own signature, but as an illustration for a volume whose author is Hugnet and whose subject matter is Duchamp. Thus, the effort to equate Duchamp's visual and written signature is undermined by a relay of signification, making it impossible to locate the precise author. As insignias of Duchamp's appropriation, the mustache and goatee emerge as false indexes of the author. Like theatrical props, they appear as objects for disguise or travesty, rather than as means for designating and legitimizing the authorial gesture. Moustache and Beard of L.H.O.O.Q. problematizes the gesture of artistic appropriation, insofar as it transitively designates the artist, en passant.

Thus neither L.H.O.O.Q. nor Moustache and Beard of L.H.O.O.Q. amount to a portrait, that is, the original act of creating a likeness, of a person either in pictures or in words. Instead, the portrait functions here in the literal sense of pour and traire (forth and draw); that is, as a drawing forth of several images (imprints) from what appears to be a single image. While trait may be interpreted to mean characteristic touch (as in trait of character), it can also mean stroke of genius or of witticism, as well as currency, a bank bill, or draft. Just as the word trait can acquire very different meanings depending on context, so the Mona Lisa, as an image, reveals itself as a repository not only of different but even of mutually exclusive images. The effort to appropriate Leonardo's portrait Mona Lisa, literally results in milking (traire ) this masterpiece. By using a reproduction of Mona Lisa, Duchamp draws forth other likenesses (appearances) that only jokingly recapture its features. The gesture of portraying is translated, therefore, into a drawing forth of other likenesses that differentially inhabit the same image. This is why the addition of the mustache and beard is not a transgressive gesture of violation or desecration. Duchamp is not negating Leonardo's work; rather, he rediscovers within Leonardo's work a set of gestures that make possible his own appropriation and reinscription of the image.

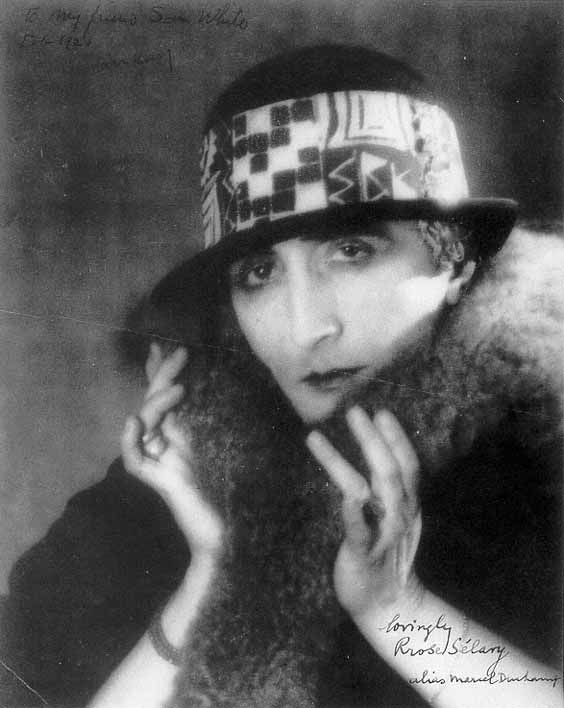

It should come as no surprise that following L.H.O.O.Q. in 1919, Duchamp inaugurates the birth of his female artistic alter ego in Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy (1920–21) (fig. 54). The portrait of the artist as female counterpart is captured by Man Ray's soft-focus picture of Duchamp masquerading as a woman (circa 1920–1921). Signed lovingly by Rrose Sélavy alias Marcel Duchamp, this photograph coyly captures Duchamp's play with the signs defining sexual identity, and by extension, identity in general. As he explains to Cabanne: "In effect I wanted to change my identity, and the first idea that came to me was to take a Jewish name. I was a Catholic, and it was a change to go from one religion to the other . . . suddenly, I had an idea: why not change sex? It was much simpler" (DMD , 64). The artistic pseudonym becomes an elaborate con joke. Rather than dissimulating identity, Duchamp's alias Rrose Sélavy disrupts the notion of artistic identity by reducing it to an arbitrary convention. Identity is reduced to a set of signs and conventions that can be manipulated, so that changing names becomes no more difficult than

Fig. 54.

Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy, 1920–21.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Samuel S. White and Vera White Collection.

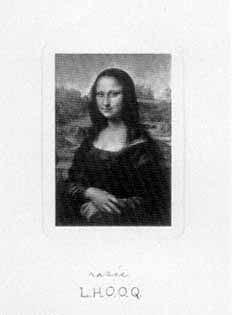

Fig. 55.

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved (L.H.O.O.Q.,

Rasée), 1965. Ready-made: reproduction of the

Mona Lisa, 3 1/2 x 2 7/16 in., pasted on the invitation

card given on 13 January 1965 on the occasion of the

preview of the Mary Sisler Collection at the Cordier

and Ekstrom Gallery, New York.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise

and Walter Arensberg Collection.

changing religion or sex. In L.H.O.O.Q. the addition of the mustache and beard uncovered the sexual ambiguity of the Mona Lisa, while in the portrait of Rrose Sélavy it is the lack of facial hair that engenders sexual ambiguity. Duchamp's shaved face and discreet smile, generously framed by a fur collar (a punning displacement of facial hair), invokes the illusion of a feminine presence. Like the Mona Lisa, it is precisely the lack of certain signs and the indexical ambiguity of other signs that constructs gender as a riddle. But this riddle functions as a pun or a switch equally designating femininity and masculinity, rather than being construed uniquely as the trademark of the feminine. Thus, it is neither the presence nor the absence of signs that generates gender, but rather their active interplay. In the same way, the question of artistic identity emerges as a game between various personas or positions without a firm referent, but constructed provisionally through their circulation. If Rrose Sélavy is Duchamp's alias (from the Latin meaning at another time), this temporal dimension, or delay, permits us to understand how s/he comes to be Marcel Duchamp at the same time s/he becomes herself.

The relation of portraiture to the artistic persona and the question of the reproducibility of a work of art come to a head in L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved (fig. 55), This work is yet another reproduction of the Mona Lisa, with an added twist: the image has not been altered in any way, other than the title. As Timothy Binkley points out, although this work is restored to its original appearance, it is not restored to its original state. He summarizes Duchamp's intervention as follows:

The first piece makes fun of the Gioconda, the second destroys it in the process of "restoring" it. L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved re-indexes Leonardo's artwork as a derivative of L.H.O.O.Q. , reversing the temporal sequence while literalizing the image, i.e., discharging its aesthetic delights. Seen as "L.H.O.O.Q. shaved," the image is sapped of its artistic/ aesthetic strength—it seems almost vulgar as it tours the world defiled.[48]

The process of "restoring" the Mona Lisa by shaving her does not, as Binkley contends, "destroy" the artistic value of this portrait by merely defiling and vulgarizing this image. Instead, by returning this reproduction to its original status—that of a mere reproduction—Duchamp reveals how the process of reproduction itself fundamentally alters the concept of artistic value. Binkley correctly notes that L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved suggests a reversal of the temporal sequence, making it seem that Leonardo's Mona Lisa would be derivative of L.H.O.O.Q.[49] This apparent dependence of the original on the copy is not entirely fictitious, however, insofar as the spectator's experience of Mona Lisa is, in fact, invariably mediated through its reproduction. The look of the spectator has already been "glazed" over by the reproduction, so that the act of seeing the Mona Lisa is merely an act of conformity, that of verifying the adequacy of the original to its copy. Rather than being a destructive or negative gesture, Duchamp's intervention clarifies the tenuous relation between works of art and their copies. Consequently, L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved does not "sap" this image of its artistic/aesthetic strength, since the artistic value of Mona Lisa hinges on its explicitly ambiguous character. With L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved, we come back full circle to a Mona Lisa that is and is not entirely herself. Duchamp's perpetuation of Leonardo's joke, that is his "mirrorical

return" on Leonardo's "mirrorical turn," restores to the viewer an image that has been reactivated through its interpretations. Rather than "restoring" a painting to his audience, Duchamp restores the concept of painting as a conceptual exercise. By delaying the sensorial impact of paint, L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved as a reproduction inscribes into the perception of the original work an interval reactivating the exchange between the spectator and the work. By seeing the image both as the original and as the reproduction, the spectator discovers the fragile interval separating art from nonart. By switching back and forth between them, the question of value emerges as the correlative of an engagement with the work: an interpretation of art as "making" that demands activity on the part of the artist as well as the spectator. Thus, the notion of artistic value emerges as an index not of the work but instead of the exchanges that it can generate between work and spectator.

Now we can begin to understand what Duchamp meant when he

Fig. 56.

Marcel Duchamp, Still-Torture (Torture-Morte),

1959. Sculpture of painted plaster and flies

with paper background on wood, 11 5/8 x 5 1/4 x

2 1/4 in. Centre national d'art et culture Georges

Pompidou, Paris.

Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

claimed that "The onlookers make the picture," or as he explained in his talk "The Creative Act" (1957): "All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act" (WMD, 140). By ascribing to the spectator the creative role of bringing the work into contact with the external world through a process of interpretation, Duchamp contextualizes the authority of the creative act. This process of contextualization is made explicit in The Box in a Valise, which replaces the museum's authority as an institution mediating our perception of art, with a valise, a portable "museum" in miniature. The spectator unpacks this valise on a table and unloads its contents manually, thereby not merely bringing these miniature reproductions into contact with the world but making these works part and parcel of the world.