1—

Muslim Visitors to World's Fairs

Now that we are not afraid of Turks, Arabs, and Saracens, the Orient has become for us a sort of hippodrome where grand performances are given. . . . We take the Orient for a theater.

Le Figaro, 26 June 1867

Muslim visitors to expositions in European and American cities were either official representatives of Muslim states or independent travelers, some of whom later recorded their observations in print. The official missions included heads of state as well as high-ranking government bureaucrats. Whatever their own motives for visiting the expositions, Muslim sovereigns who attended immediately became part of the display, often as the major attraction. Members of exposition commissions also received due attention from the Western press. And the commissions themselves published books about their cultures, documents that illustrate not only the official self-perception but also the perceptions governments hoped to elicit among Westerners. As part of the displays, indigenous people were brought in to represent anthropological "types." This idea may have derived from the French researcher Joseph Marie de Gérando (1772–1842), who, in the belief that humans could be understood in light of methodological observations carried out on "savages," had proposed to transport such "pure" specimens to France.[1]

Whereas official visitors to the fairs brought their lives and cultures to Europe and America, independent travelers in their reports took the expositions to audiences back home. Exposition fever was widespread, and literature on the fairs included travel accounts, newspaper and magazine articles, novels, and even poetry, all in tones ranging from the didactic to the lyrical.

Displays of Indigenous People

The young disciplines of anthropology and ethnography popularized their methods and publicized their discoveries at the nineteenth-century universal expositions. In a provocative study, Johannes Fabian defines anthropology as "a science of other men in another tune," the notion of "another time" signify-

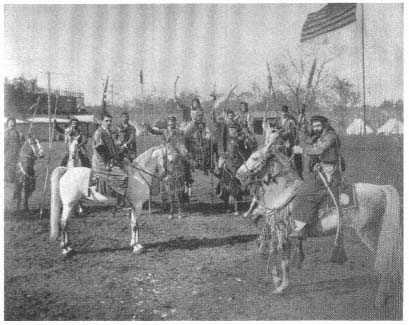

ing not a chronological past but the frozen status of certain societies and cultures. Although, as Fabian points out, these "other men are our contemporaries," they are situated at a temporal and spatial distance.[2] The displays of non-Western peoples at the nineteenth-century world's fairs were organized around the anthropologist's concept of distance. "Natives" were placed in "authentic" settings, dressed in "authentic" costumes, and made to perform "authentic" activities, which seemed to belong to another age. They formed tableaux vivants, spectacles that fixed societies in history.[3] Mixing entertainment with education, these spectacles painted the world at large in microcosm, with an emphasis on the "strangeness" of the unfamiliar (Fig. 1). Describing a procession to be held at the Midway of the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, the Chicago Tribune emphasized its theatricality:

It will be a unique procession, one which cannot be seen elsewhere, and one which never may be seen here again after the Fair closes. Headed by the United States regulars, there will follow in picturesque array Turks with Far-Away Moses leading them, Bedouins, sedan bearers, Algerians, Soudanese, the grotesque population of the Cairo Street, with its wrestlers, fencers, jugglers, donkey boys, dancing girls, eunuchs, and camel drivers, Swiss guards, Moors and Persians, the little Javanese, South Sea islanders, Amazons, Dahomans, etc. . . . The march of this heterogeneous conglomeration of strange peoples, brilliant in color and picturesque in attire, will be enlivened by music of all kinds. . . . It will be a picture in miniature of the World of the Orient in this newest city of the Occident, and a day's diversion in the routine of sight-seeing which will be of an agreeable if not exciting character to witness the queer and strange spectacle.[4]

Such spectacles also served the politics of colonialism. The display of both subject peoples and products from foreign possessions made colonialism concrete to those at home and reaffirmed the colonizing society's "racial superiority," manifest in its technical, scientific, and moral development—as the French prime minister Jules Ferry argued in the 1880s.[5] The inclusion of native populations in the fairs was much discussed at the time. An anonymous article on the Tunisian section in 1889 argued that it was essential to display the colonized people "to give more reality and life to the buildings [erected on the site]."[6] Furthermore, without the display of colonial subjects, an exposition would fail

Figure 1.

A parade by Arabs in the Trocadéro Park, Paris, 1900 ( L'Exposition de Paris, vol. 2).

to "embrace all phases of life and work in the colonies."[7] When the organizers of the Universal Exposition in 1900 considered excluding displays of people from the French colonies, they encountered strong opposition. Charles Lemire, the honorary resident general, argued that because the French needed to be better informed about the races inhabiting the colonies and protectorates, the fairs should show the different racial types in appropriate environments. At the same time, the natives would have the opportunity to acquaint themselves with the metropole. Lemire suggested how the exposition could diffuse information about the colonized and the colonizer:

Useful products, racial types, specimens of ancient and modern art, these are the indigenous elements to conglomerate; French products, resources of the metropole, contact with the French [in France], these are the continental elements to offer to the indigenous.[8]

According to the anthropologist Burton Benedict, human displays at the world's fairs were organized into national and racial hierarchies.[9] The nine-

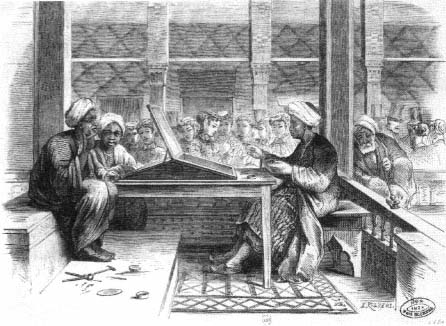

Figure 2.

Filigree artisans in the Egyptian bazaar, Paris, 1867 (Bibliothèque Nationale.

Département desEstampes et de la Photographie).

teeteenth-century "scientific" approach, based on an interpretation of Darwinian theories, emphasized classification,the diversity of racial types, and the hierarchy of these types.[10] Benedict summarized the classification of human types at the fairs as follows: (1) people as technicians, with a technician acting as part of a machine on display; (2) people as artisans, with an emphasis on tradition and ethnicity as well as the "handmade" qualities of the products; (3) people as curiosities or freaks, with an emphasis on abnormal physiology and behavior; (4) people as trophies, most typically the conquered displayed by the conquerer in special enclosures; and (5) people as specimens or scientific objects, as subjects of anthropological and ethnographic research.[11]

The displays of Muslim people fit all these categories except the first. Machines belonged to the advanced nations, and in only a few cases, which involved rather primitive inventions, were Muslims associated with them. One such example was the "Turkish fire engine" in the Columbian exposition, "carried on a sort of sedan chair arrangement by as many bare-legged Turks as can get hold of it."[12]

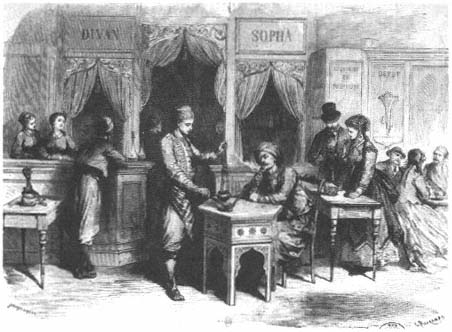

Figure 3.

Turkish café, Paris, 1867 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Département des Estampes et de

a Photographie).

Figure 4.

Ironsmith from Kabyle, Paris, 1889

(Bibliothèque Nationale, Département

des Estampes et de la Photographie).

Benedict's second category, artisans, filled the bazaars of the Muslim quarters at the fairs (Figs. 2–4). They included a Tunisian barber and café attendants in 1867,[13] Algerian cobblers and "handsome Kabyles from Constantine"

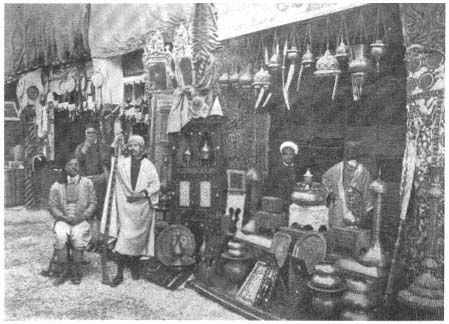

Figure 5.

Tunisian souk in the Trocadéro Park, Paris. 1900 (Quantin, Exposition du siècle ).

in 1878,[14] and Turkish street confectioners in 1893 in Chicago.[15] But perhaps the most complete crafts fair was provided by the Tunisian section of the 1900 exposition in Paris (Fig. 5). The thirty-seven crafts "typical of Tunisia," including jewelry making, weaving, embroidering, basket weaving, shoemaking, and woodworking, were "chosen in order to give the total picture of the local indigenous industry."[16] The protectorate administration was particularly proud of this section because it considered itself a savior of the "indigenous artistic industries" faced with the threat of modernization.[17] The Tunisian display was also seen as a reaction against the simpleminded entertainments in other Islamic displays: "[It] does not attract visitors by its tumultuous belly dances. It presents itself in its everyday clothes, in its honest work clothes."[18]

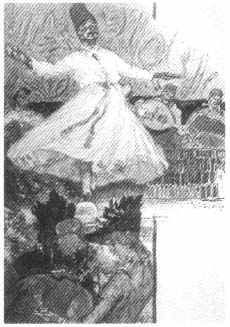

Muslims were often treated as curiosities in the exhibitions, not so much for any physiological abnormalities as for differences in behavior, customs, and the traditions they acted out before large audiences in the Islamic quarters built on the fair grounds (Figs. 6–7).[19] Theater, music, and dance in "exclusively

Figure 6.

"Bedouins in Their Encampment." Chicago, 1896 ( The Dream City, vol. 1.).

Figure 7.

Whirling dervish on the Rue du Caire,

Paris, 1889 (Revue de l'Exposition

universelle de 1889, vol. 1).

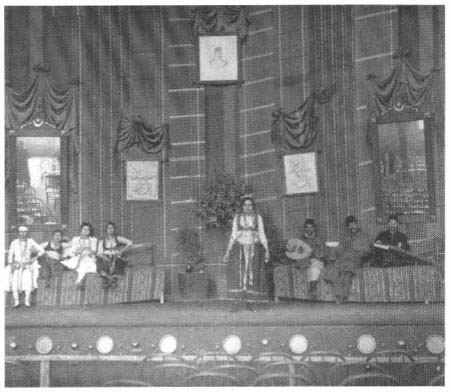

ethnic character" became indispensable attractions at every fair. Ben Truman, an American observer, described the Turkish theater at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition:

Eighteen houris of the Orient and sixty-five men have been picked up from the companies of Constantinople, who dance, play, sing and form an orchestra, a stock company and a chorus. The complement is fully made-up, and there are soubrettes in baggy trousers, heavy tragedy in a fez, and low comedy in a turban.[20]

In 1900 the Egyptian theater in Paris reproduced vignettes from Egyptian and Sudanese life—at times even reconstituting social scenes from antiquity—in luxurious settings with actors in rich and diverse costumes.[21] In the same year the "Armenian theater" in the Ottoman section produced "operettas" based on Turkish daily life and customs but with Italianized music to make the performances "more acceptable to European ears."[22] The use of such music was, however, an exception; the music played in Islamic quarters was unfailingly described by European and American reporters as "bizarre," "strange," "wild," and "irritating to European ears,"[23] even as it was felt to maintain the cultural integrity of the compounds. Ben Truman summarized the prevailing view in describing the musical performance at the Turkish theater in 1893 as "mournful, weird, plaintive and funereal by turns—never lively or rhythmical; yet when floating out from a latticed window or portiered doorway, not entirely unenchanting."[24] More serious accounts of Arabic music also emphasized its "indefinite repetitions" and "monotony."[25]

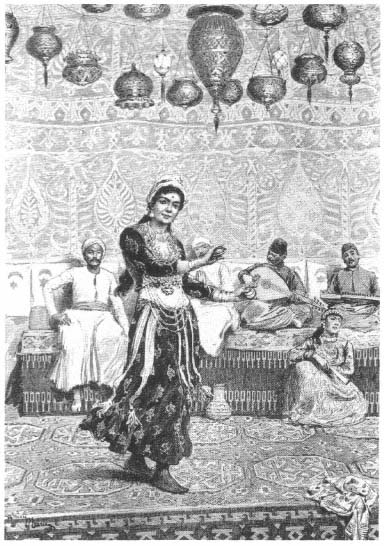

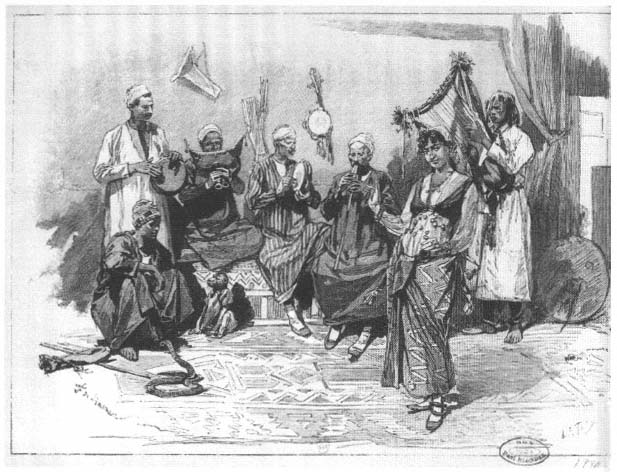

In all performances the belly dance was the highlight (Figs. 8–10). Catering to fantasies about harem life, belly dancers attracted great crowds and achieved major commercial success; in 1889 in Paris, the "danse du ventre made all of Paris run [in its orbit]," and an average of two thousand spectators flocked to watch the belly dancers every day.[26] One French journalist cynically noted that the ten words in French one of the "exhibitors of bellies" had learned and repeated all day long were well chosen: "La danse, . . . c'est épatant! entrez, mousiu, c'est le moment psychologique" (The dance . . . it's terrific! Enter, Monsieur; it is the psychological moment!).[27] In 1893 a cartoon in a humor

Figure 8.

Alma Aicha's dance in the Egyptian café of the Rue du Caire, Paris, 1889

(Bibliothèque Nationale, Département des Estampes et de la Photographie).

Figure 9.

Sudanese musicians and dancer in the Egyptian café of the Rue du Caire, Paris, 1889

(Bibliothèque Nationale, Département des Estampes et de la Photographie.).

Figure 10.

A dance in the theater of Cairo Street, Chicago, 1893 ( The Dream City, vol. 1).

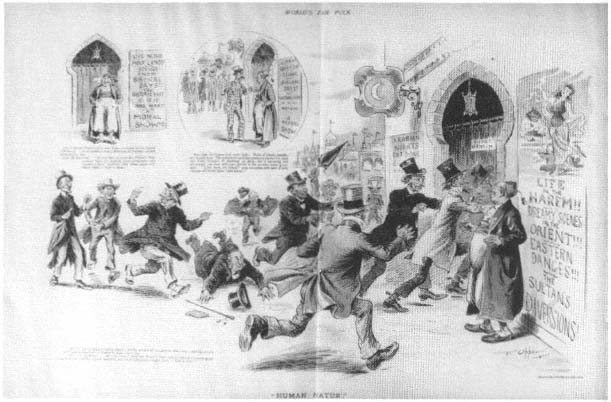

magazine, World's Fair Puck, elaborated on the business potential of the American obsession with the harem and the belly dance in Chicago (Fig. 11).[28]

The enthusiastic reception of the belly dance was closely linked to the Parisian entertainment industry in the nineteenth century, specifically to the popular dances performed in the cabarets, café-concerts, jardins d'hiver, and bals publics . The cult of the star, which originated in these establishments, extended to the Fathmas, Feridjées, Aichas, and Zohras who took their place among the erotic female dancers of the time: La Goulue (The Glutton), Nini Pattes en l'air (Nini Paws-in-the-Air), Môme Fromage (Mistress or Kid Cheese), Grille

d'Egout (Sewer Grate), and many others.[29] The Islamic theaters at the expositions complemented the city's own places of pleasure—its streets, café-concerts, and cabarets.[30] In these theaters, amid architecturally "authentic" settings, belly dancers presented the element of Muslim life most intriguing to Europeans, one that for at least seventy-five years had been a focus of Orientalist painters and writers. The descriptions of the performances were at once evocative and condescending. This passage from a long article in the Figaro illustré is representative:

Men and women dressed in transparent silks and sumptuous embroideries reclined on rugs and cushions and, smoking the narghile and drinking rose- and liquor-flavored sherbets, awaited the delicious keif (pleasure). . . . As though pinched by a needle, [the dancer] started moving with hideous contortions that

Figure 11.

Cartoon "Human Nature," Chicago, 1893, with detail ( World's Fair Puck, 4 September

1893). The detail shows, at left, a Turkish entrepreneur on the Midway who hopes to

attract large Crowds to biblical scenes from the Holy Land; after failing, he gets

advice from a local businessman. With the sign changed from "Life in Holy Lands,

Scenes from Biblical Days" to "Life in the Harem, Dreamy Scenes in the Orient,

Eastern Dances, the Sultan's Diversions," crowds flock to the booth.

all the Fathmas and Feridjees of the feasts of Neuilly have saturated us with. With the vibrations of her hips and her torso, she gives the illusion of a sea that calms down, one where the long slow waves die on the sand.[31]

The account further referred to sentiments aroused by The Thousand and One Nights, to images of prayers recited in front of mosques, and to ferocious men from "ancient times."[32]

As Parisian dance and the belly dance exchanged characteristics, both were transformed. For example, in 1889 the belly dancers' accessories were limited to swords and mirrors: in the dance of the sword, the dancer's clattering swords accompanied the violins and the violas; in the dance of the mirror, the dancer flirted with her reflection in a "real pantomime of conquetry."[33] The

belly dancers in the Egyptian theater in 1900 used more elaborate props: several glasses on the belly, a narghile or candelebra on the head, or a chair in the mouth (Figs, 12–13).[34]

In colonial displays people were frequently displayed as trophies. Artisans working in traditional crafts in small settings that re-created the "authenticity" of their place of origin were "trophies in special enclosures."[35] "Colonial soldiers" were presented similarly in 1889 and in 1900, when armed Algerians in their local costumes, in a setting designed to evoke the colony, "gave legitimate satisfaction to [French] patriotic feelings."[36]

People were presented as subjects of research more often than in any other guise at the fairs. The aura of these displays was "scientific," as was the language used to describe them. In 1867 a certain Docteur Warnier compared the physiology and character of the Arab and the Berber. The Arab was tall and thin, with a "pyriform" skull, a narrow forehead, an arched and bony nose, and black eyes, hair, and beard; the Berber was of medium height, with a large round skull, broad straight forehead, fleshy nose, square jaw, and eyes, hair, and beard varying from black to red. Whereas the Arab was a fighter who enjoyed war but was otherwise undisciplined, a "born enemy of work," the Berber was the opposite: he was docile, worked hard, and because of his intelligence could "become a devoted auxiliary of European and Christian colonization." The Arab looked Asiatic, the Berber European.[37]

The Tunisian musicians in Paris in 1878, of a "type bien africain," displayed the traits of a "beautiful race, indolent, sleepy, but with features not lacking nobility or energy";[38] the "Arabesque races" on the fairgrounds in 1889 were of the "Israelite type";[39] the Arabs of the Algerian theater were "generally handsome, having preserved the nervous grace and the pride of nomadic races."[40] Behavioral attitudes were also displayed. The Arabs of the Camp of Damascus in the Turkish village in Chicago "squatted about as at home. They had little occupation, except the smoking of the narghile, without which [they] would consider [their] hours of leisure devoid of any pleasure."[41]

The "scientific" display of indigenous peoples seemed to require that all the races from a specific region be included to give fairgoers as complete a picture as possible. The Cairo Street in Chicago had "Jews, Franks, Greeks, Armenians, Nubians, Sudanese, Arabs, and Turks . . . representing faithfully the population of the old city of Egypt."[42] The Tunisian section in 1900 had 140

Figure 12.

Dance of the narghile, Paris, 1900

(Figaro illustré, no. 124, July 1900).

Figure 13.

Dance of the chair, Paris, 1900

(Figaro illustré, no. 124, July 1900).

Jews and Muslims (Moors and Berbers), "representing the different types one encounters in Tunisia."[43] The contemporary press, echoing the notion of a microcosm, commonly published images of all the racial types to be seen on the fairgrounds. The caption for a photographic collage from the Colombian Exposition dwelt on the diversity of the thirteen racial types depicted:

To say that all these characters were taken from a street less than a mile long, would seem to indicate a most heterogeneous massing of nations, but when is added the thought that they are but types, and that each one represented from

twenty to fifty more, the idea becomes quite overpowering. These individuals represented Europe, Asia, Africa, North America, South America, and the islands of the South Pacific.[44]

The hierarchy of races in the world's fair displays made the premises of nineteenth-century anthropology and ethnography constituents of mass culture in Europe and America. Indeed, the reception of non-Westerners at the expositions demonstrates this clearly. For example, in 1889 Parisian women "very quickly learned to treat the indigenous with a maternal charity; . . . they considered them big children (grands enfants )."[45]

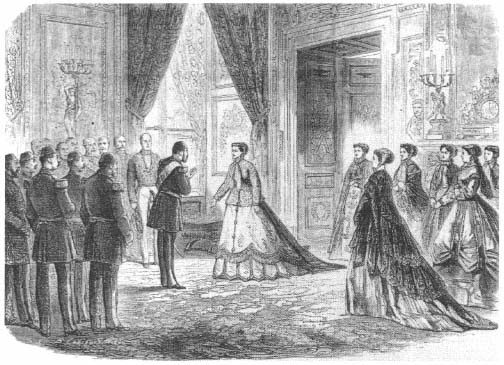

Muslim Sovereigns at the Fairs

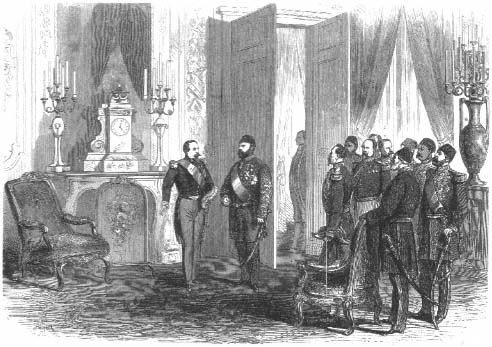

The 1867 Universal Exhibition in Paris was marked by important visits from two Muslim sovereigns: Governor Isma'il Pasha of Egypt and, some weeks later, Sultan Abdülaziz of the Ottoman Empire, the first in his dynasty to leave the empire for a purpose other than war (Figs. 14–15). These visits were major events, chronicled in minute detail. Parisians were intensely curious about Isma'il Pasha and Abdülaziz, both of whom traveled with their entourages and were honored guests of Napoleon III. As one newspaper noted at the time, a few days after the sultan's arrival "the Parisian population [was] divided into two very distinct classes: those who had seen the sultan and those who had not."[46] A ceremony at the Palais d'Industrie, where the sultan sat next to Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie, attracted between "twenty and thirty thousand people."[47]

Isma'il Pasha and Abdülaziz became the highlights of the exhibition. In Abdülaziz's honor, a splendid décor was put up in the Palais d'Industrie. A white drapery studded with golden stars lined the semicircular glass roof, crimson velvet draperies trimmed with gold lace hung from the galleries, and the imperial throne with its towering golden canopy dominated the room. Here, as if on a magnificent stage, the French emperor and empress sat with the sultan while an orchestra of twelve hundred musicians played.[48] The three rulers were as much on display as the different products exhibited on an elevated platform before the throne.

Figure 14.

Reception of Isma'il Pasha by Empress Eugénie at the Tuileries, Paris, 1867 ( L'Illustration, 29

June 1867).

One journalist interpreted the warm welcome Paris gave Abdülaziz as the result of curiosity rather than sympathie .[49] Another, criticizing the widespread perception of the sultan as a dazzling monarch from The Thousand and One Nights, surrounded by odalisques, drunk with perfumes, and adorned with precious stones and gold, argued that the sultan was instead a generous, good man, extremely intelligent and well educated, who valued work, order, and justice above all and who respected the rights of Christians in his empire. "This is the man," he concluded, "without doubt, not as marvelous as we believed, but wiser and more human."[50] Isma'il Pasha was presented as similarly tolerant because all citizens of Egypt, regardless of belief, could be elected to the Egyptian parliament.[51]

In Innocents Abroad, however, Mark Twain depicted Abdülaziz as a "weak, stupid, ignorant [man] who believe[d] in gnomes and genii and the wild fables of the Arabian Nights."[52] Describing the public appearance of Napoleon III

Figure 15.

Sultan Abdülaziz's visit to Napoleon III in the Elysée Palace, Paris, 1867 ( L'Illustration,

13 July 1867).

and Abdülaziz on the Place de l'Etoile, Twain argued that the two men represented opposite worlds:

Napoleon III, the representative of the highest modern civilization, progress, and refinement; Abdul-Aziz, the representative of a people by nature and training filthy, brutish, ignorant, unprogressive, superstitious—and a government whose Three Graces are Tyranny, Rapacity, Blood. Here in brilliant Paris, under the majestic Arch of Triumph, the First Century greets the Nineteenth![53]

The populace were disappointed by the outlook, disposition, and conduct of the Muslim rulers, who, except for the red fez, dressed in European-style clothes. They were socially graceful,[54] and Isma'il Pasha, who had been educated at the Ecole Polytechnique in Paris, even spoke excellent French—"le français le plus pur, sans le moindre accent."[55] They demonstrated their fine

taste by their interests. Abdülaziz, for example, stopped in front of "les plus beaux meubles" and "les bronzes les plus artistiques" in the furniture section of the exhibition before going on to visit the fine arts gallery.[56]

What were the governor's and the sultan's goals in visiting the exposition? According to one French journalist, Abdülaziz intended to tell the world that despite the reputation of his empire as the "sick man of Europe," he played a crucial role as the leader of the Muslims because the people of Asia and Africa still followed the teachings of the Qur'an.[57] As caliph, he was the omnipotent Muslim ruler. Yet Abdülaziz also pursued a Western model of "progress" and wanted to be recognized for his institutional reforms. Similarly, Isma'il Pasha's goal was to demonstrate his alliance with Europe by announcing the modernizing transformations in his own country.

Both Abdülaziz and Isma'il Pasha were intent on reshaping their cities according to European models—a goal reflected most dramatically in the physical transformation of Istanbul and Cairo. In Istanbul, following a fire that destroyed a huge section of the city in 1865, a campaign was launched to replace the irregular urban fabric—crooked streets and dead ends—with straight, regular streets and grid patterns. Modern services such as street lighting and cleaning were introduced at the same time.[58] The new plans were believed to match those of "the most recently designed places in the world,"[59] the reference being to the rebuilding of Paris under Napoleon III and his prefect, Baron Haussmann.

The changes in Istanbul were incremental and eclectic, determined mostly by fires and the rebuilding that followed them. In contrast, city building in Cairo was comprehensive.[60] A new quarter of Cairo, named Ismailiyya after the governor, extended the city to the west with a design that superposed a pattern of radial streets on a grid. Long avenues ended in squares or ronds-points; monuments and public buildings defined the ends of vistas.[61] The model was once again Haussmann's work in Paris. Indeed, French architects, landscape architects, and gardeners were commissioned to beautify Cairo.[62] Nubar Pasha, president of the conseil des ministres and head of the Egyptian Commission to the 1867 exposition, later criticized Isma'il's obsession with the "toilette du Caire" and accused him of misunderstanding the meaning of "progress" by equating it with imitating in Cairo what had been done in Paris—"des boulevards, des jardins, des embellissements de toute nature" (boulevards, gardens,

beautification of all kinds).[63] Because Isma'il Pasha needed to borrow money from European powers to carry out his plans, his purpose in visiting Paris in 1867 went beyond the strengthening of cultural ties between the two countries. In 1868 France loaned Egypt (through the Société Générale) 296 million francs to be paid in thirty years with interest.[64]

The visits of Muslim sovereigns to the 1867 Paris Universal Exposition were significant for several reasons. Both Isma'il Pasha and Sultan Abdülaziz used the opportunity to convince European powers of their commitment to modernization and hence their desire to become part of the European system. Their presence made a difference vis-à-vis the public, shattering romantic beliefs and demystifying certain stereotypes. Moreover, their firsthand look at European life and the externalized forms of European culture helped to consolidate their belief in the radical policies adopted at home. This effect was especially important for Abdülaziz, who was making his first trip to Europe. For Isma'il Pasha, who had lived in France, the expedition was an occasion to catch up with the social and physical transformation of Paris.

Iranian shahs were the next visitors to international fairs. Westerners did not express as keen an interest in Iran as in the Ottoman Empire and Egypt, however, most likely because of Iran's lesser effect on European history. Contacts between Europe and Iran were not significant for Iran either, and European ideas of reform penetrated the country only much later. Not until the 1870s did Shah Nasir ad-Din, stimulated by the technological achievements of the West, begin his modernizing reforms, which were initiated by the diplomatic corps.[65] In fact, when Napoleon III invited Shah Nasir ad-Din to Paris in 1867, it was the Iranian ambassador to Istanbul, Mushir ad-Dawla, who urged the shah to accept the invitation, arguing that the trip would "give new life to the state and nation of Iran and leave the Shah's great name in the history books." But at that point, Nasir ad-Din was not interested in European contacts, and even the example of Sultan Abdülaziz would not convince him. Instead, two years later, he took a trip to holy places.[66] The diplomats ultimately persuaded him to travel extensively in Europe. On his first trip in 1873 he stopped in Moscow and London to establish closer political ties with Russia and England and in Vienna to see the universal exhibition.[67] He visited Europe again in 1878 and 1889 during the Paris expositions. Shah Muzaffar ad-Din traveled to Paris to see the 1900 exposition.

By the turn of the century the novelty of exotic visitors to the expositions had worn off, and Europeans had become accustomed to distant, unfamiliar lands coming to them, complete with their rulers. In tired tones, later accounts repeated the old themes. For example, during Muzaffar ad-Din's visit, the popular press reported on his human qualities, his kindness, his love of children, and especially his simplicity; journalists also described his clothes at length. One gave a full account of his traveling wardrobe, which consisted of costumes for official visits, receptions, and "promenades" and a special cloak. All the glamour of the "Oriental" ruler had dwindled to this cloak, said to be adorned with "about one hundred million precious gems."[68]

Commissions to Expositions and Their Publications

The 1867 Universal Exposition generated several important books by the Egyptian and Ottoman commissions. These publications discussed the themes of the displays as well as the contemporary trends and developments in each nation considered worthy of international exposure. Isma'il Pasha appealed to French scholars to prepare the texts on Egypt: these scholars in turn focused on the aspects of Egypt that most interested them at the time. Alongside the growing field of Egyptology, the history of Egyptian antiquity acquired prominence. Egyptian publications also persisted in presenting the reforms of the 1860s as follow-ups of the Napoleonic mission. The Ottomans, in contrast, relied more on local sources and focused on Ottoman culture—both past and present—though they also reflected on efforts to modernize institutions along European lines.

The authors of the publications on Egypt were Charles Edmond and Auguste Mariette, also known as Mariette-Bey. Charles Edmond was a historian and an archaeologist, Mariette-Bey a well-respected Egyptologist. Both were savants in the Napoleonic tradition of the 1800s that had resulted in the Description de l'Egypte —the monumental document prepared by Napoleon's team of researchers during the Egyptian campaign.[69] Charles Edmond's and Auguste Mariette's books described the Egyptian exposition and gave general information about Egypt. Edmond's L'Egypte à l'Exposition universelle de 1867 (Paris, 1867) is structured according to the display, with each section representing a chronological period (antiquity, Middle Ages, and modern times), and in-

cludes historical information together with a description of the particular pavilion. Although the three-part historical division seems balanced, the greater amount of information on Egyptian antiquity meant that this period overshadowed the others. Egypt's Muslim architectural heritage of the Middle Ages, in contrast, was treated briefly and only as an antithesis to Western architecture, because, according to Edmond, Islamic architectural compositions relied on chance rather than reason.[70] The author's national pride and his assumption that France was the center of modern European civilization color the text even when his purpose is to glorify Egypt's Islamic monuments: "It seems very likely that in the creation of Mohammadan architecture Egypt played the role that France, justifiably, is honored with in the invention of the beautiful Gothic buildings of our Middle Ages: she is the initiator."[71]

The independence of Egypt from the Ottoman Empire—another theme echoed from the Napoleonic campaign—was asserted in the discussion of Islamic architecture. Edmond criticized Ottomans for their inability both to invent their own art and to assimilate Arab art with intelligence and taste: the mosques of Istanbul were mere copies of Hagia Sophia, yet their interiors were covered with arabesques and inscriptions. "After having stolen the Arab genius, [the Ottomans] let it die."[72]

In his last chapter Edmond discussed modern Egypt, which he felt had been "chosen to initiate the rest of the Orient to modern civilization." Not only Egypt's strategic position but also its luck with "great men" had opened the doors to progress. Napoleon I had begun the process of modernization; his contribution was invaluable for "the prestige of his name and his victories." He had "made the Oriental genius return to itself and opened [it] to ideas of reform."[73] Muhammad 'Ali and Isma'il Pasha were Napoleon's faithful followers.

Mariette-Bey credited Muhammad 'Ali and his dynasty with introducing modern civilization to Egypt, but he noted among the highlights of recent Egyptian history the "adventurous though brilliant expedition" of Napoleon. He praised the people of Egypt for the remarkable continuity of their history and explained this "great good fortune" by comparing them to the people who lived south of the Equator along the Nile. While these "races" to the south were "uncultivated, wild, incapable of governing themselves," those in Egypt were "docile, prompt to do good things, easy to instruct, and capable of prog-

ress." Such qualities would allow Egypt to "march grandly along the road to progress" and would "attract the attention of the whole world."[74]

Mariette-Bey did not elaborate on the modernization of Egypt and its current role in the international scene. He focused instead on his own field of expertise, Egyptology. In both Aperçu de l'histoire ancienne d'Egypte pour l'intelligence des monuments exposés dans le temple du Parc égyptien (Paris, 1867) and Description du Parc égyptien (Paris, 1867), the Egyptian displays were his starting point for discussions of the art and archaeology of the ancient kingdoms.[75] His penchant was clear in his definition of the "temple" in the 1867 exposition as the "principal building of the Egyptian Park."[76] Despite this nod toward the later history and current civilization of Egypt, the country's importance lay in the distant past.

Among the Ottoman officers at the 1867 fair was Salaheddin Bey, the head commissioner of the Ottoman Empire, whose book, La Turquie à l'Exposition universelle de 1867 (Paris, 1867), presented the Ottoman displays. Like Charles Edmond's L'Egypte à l'Exposition universelle de 1867 in format and contents, Salaheddin Bey's book also discussed the displays, summarizing through them the history of the Ottoman Empire and its participation in modern civilization. The overall tone was imperial: the dedication was to Sultan Abdülaziz, whose visit was compared to an act of the caliph Harun al-Rashid ten centuries earlier. Harun al-Rashid, to acknowledge his friendship with the "greatest monarch of the Occident," had sent him valuable presents. Now, at the invitation of the emperor of France, Abdülaziz was honoring France with his own presence.[77]

The imperial and sanguine tone of this document did not obscure the foreign influences that had infiltrated Ottoman culture.[78] In this respect, it is an important text, which illustrates how the Easterner affirmed an image of his culture constructed by Europeans. Salaheddin Bey's goal was to present the Ottoman Empire as modern and advanced; to ensure the acceptance of his work in the West, he adopted European conventions. For example, when describing the Ottoman pavilions, he often employed the vocabulary of rationalist architects, noting that the structures were designed according to certain scientific "principles."[79] Yet, Salaheddin Bey's observations were so much influenced by Western thought that they reflected its contradictions: in his analyses he paid lip service to rationalism while writing passionately about exoticism, as if he

were a romantic outsider fantasizing about the unknown. Hence he noted that the buildings on the Champ de Mars were "animated by a frank and naive gaiety,"[80] but he also complained that despite expert construction, they failed to convey the flavor of the real Orient. The mosque of the Champ de Mars, for example, lacked "the broad landscape, the great sun, and the calm sea—all the poetic things that make a beautiful frame in the Orient."[81] Out of context, the building "lost the marvelous placement it enjoyed back there, in Bursa, surrounded by shady gardens and pretty houses in painted wood with windows embellished by covered balconies, or chahnichirs, and frequented by a crowd in gaudily colorful clothes."[82]

Describing a typical crowd in a mosque, Salaheddin Bey echoed the familiar tone of European travelogues:

The pious imams and the simple believers, barefoot as a sign of deep respect, maintain a meditative silence and pray by striking their foreheads against the ground to adore God. The muezzin, in his clear, sharp voice, casts to the four winds from the height of the minaret the profession of the Muslim faith, the formula of belief La illah el Allah! Mohammed reçoul Allah! There is only one God! Mohammed is the prophet of God![83]

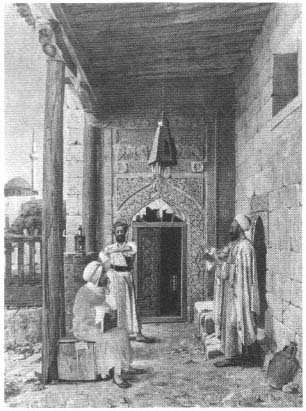

The Ottoman displays in 1867 were enriched by numerous photographs by the Abdullah brothers of Istanbul depicting Turkish life and a cross section of the population; by a watercolor portrait of the sultan by Amadeo Presiozi; by French artists' paintings of Ottoman subjects; and by three works (Gypsy Camp, Zeibek on the Lookout, and Death of Zeibek ) by the Ottoman painter Osman Hamdi, who at the time was studying under Gustave Boulanger and Jean-Léon Gérôme in Paris.[84] Osman Hamdi continued to play a significant role in representing nineteenth-century Ottoman art and culture at world expositions after 1867.[85] His paintings, often included in the Ottoman displays, contributed to the making of a new Ottoman image.

Osman Hamdi is a controversial figure in Ottoman art and intellectual history. His Westernized upbringing and his education in France were reflected in his vision of Ottoman society, yet Osman Hamdi maintained a considerable critical distance. Although his technique and the settings he painted belong to the Orientalist school, his topics, as statements about Ottoman culture and so-

Figure 16.

Osman Hamdi, Discussion in Front of a Mosque Door, c. 1900

(Painting and Sculpture Museum, Istanbul).

ciety in the new age, distinguish him from the artists of this school. Osman Hamdi's men and women—dressed in the colorful garments of the Orientalist mode and placed in "authentic" architectural settings—are thoughtful, questioning, and acting human beings (Fig. 16) who display none of the passivity and submissiveness of Eastern subjects characteristic of the Orientalist tradition. The Orientalist paraphernalia in Osman Hamdi's paintings comments on the "difference" between Ottoman society and other societies rather than its "otherness," which European artists depicted.[86] To this extent Osman Hamdi's paintings are critiques of the Orientalist school by a "resistant" voice,[87] whose power derives from the painter's thorough acquaintance with the school's techniques and conventions. These paintings are carefully composed essays on Ottoman society, expressed in a Western vocabulary.[88]

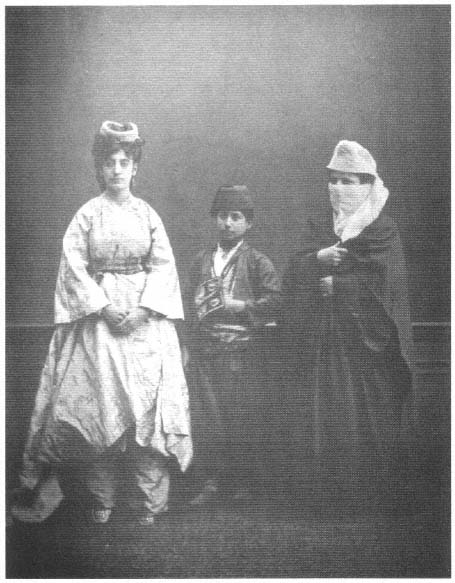

Osman Hamdi also contributed to a book, Les Costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873 (Constantinople, 1873), published on the occasion of the Universal Exposition in Vienna, which documented Ottoman costumes according to class and region, with photographs by Pascal Sébah (Fig. 17). The photographs all had the same format, and all were taken against a bare wall. The scenographic backgrounds of popular postcards and Orientalist paintings were deliberately avoided. This was a scholarly study of typology, aimed at an international audience:[89] "For artists, this will be an important mine of materials, for people of fashion, an interesting and instructive recreation; meanwhile the philosopher and the savant will find here numerous topics for beneficial reflection and fruitful study."[90]

Les Costumes populaires went beyond documentation to show "the diversity in the unity" of Ottoman culture.[91] The authors thus differentiated costume, which responded to conditions such as climate or profession, from clothing styles that changed constantly according to fashion.[92] But even as they revised one stereotype of Ottoman culture by insisting on its richness and pluralism, they repeated a false generalization common to European interpretations: by failing to note transformations over time and by characterizing "costumes" as timeless, they froze the culture historically.

The second Ottoman publication for the 1873 exposition, Usul-u mimari-i Osmani or L'Architecture ottomane (Constantinople, 1873), focused on Ottoman architecture. A collaborative effort by Marie de Launay, Montani Effendi (an Italian architect), Boghos Effendi Chachian (an Armenian architect), and M. Maillard (a French architect), the book illustrated the superior qualities of Ottoman monuments and reintroduced them to modern architects. The idea for this work came from Edhem Hamdi Pasa, Osman Hamdi's brother, who was minister of public works and president of the Ottoman imperial commission for the exposition. Edhem Pasa specified that the book should deal with the "rules of Ottoman architecture" and should contain "all the necessary drawings in addition to the historical and artistic descriptions of Ottoman monuments."[93]

The format of Usul-u mimari-i Osmani followed that of similar books on Western architecture. The book discussed the degeneration of Ottoman architecture in the nineteenth century and suggested remedies. A "Historical Précis" of the most important Ottoman monuments analyzed the causes of their

Figure 17.

Turkish women of Constantinople dressed for home (left) and the street (right);

in the center is a schoolboy (Hamdy Bey and Marie de Launay, Les Costumes populaires ).

decline. French architects, engineers, and artists were seen as a destructive influence, one that had led to a loss of purity in Ottoman architecture. The authors accused the nineteenth-century architects of Istanbul of experimenting with all known styles: "Trying in vain to adopt them, sometimes one by one, sometimes in a confusion that is ridiculous and inadequate to the requirements of Ottoman buildings—religious and other—they produce nothing but monstrous and dull designs." If Ottoman architecture continued to imitate European styles, it would soon disappear. During Abdülaziz's reign, however, some positive tendencies had emerged, and a "national art" based on a "renaissance" of Ottoman architecture, an "école néo-turque," was in sight.[94]

A chapter titled "Technical Documents" outlined the rules of Ottoman architecture. With Vitruvius's system of classification as a model, the Ottoman orders were divided into the ordre echafriné, ordre brechiforme, and ordre crystallisé, corresponding to the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders. Each was described in detail, and each description ended with a few Vitruvian statements: the ordre echafriné was appropriate for the lower levels of galleries, for shops, and for every building type that required simplicity. The brechiforme was severe and heavy and was not used in civil architecture. The playful crystallisé was suitable for the interiors of civic buildings.[95]

The authors argued that the Ottoman orders, which had created many beautiful buildings in the past, should still be used because "they presented more subtlety than the commonly known classical orders." They believed that by reorganizing the principles of Ottoman architecture into a doctrine, they were serving art in general.[96] Their objective was to make a place for Ottoman architecture within the wide spectrum of Western architectural styles and to encourage the use, at home and abroad, of a neo-Turkish style.

A third book prepared under the patronage of the Ottoman government for the Viennese exposition was Le Bosphore et Constantinople (Vienna, 1873), by P. A. Dethier, the director of the Imperial Museum in Istanbul and a member of the Ottoman commission to the exposition. He noted that the Viennese exposition offered a good stage from which to present the Ottoman capital to people from around the world. The book covered historic (Byzantine and classical Ottoman) monuments as well as the major nineteenth-century buildings, such as the university and the Ministry of Defense.

These three Ottoman publications resulted from serious and systematic studies that followed Western precedents and formats. They reflected the larger goal of generating respect in the West for the Ottoman Empire, which would continue to maintain its cultural identity. For similar reasons a large collection of Ottoman photographs was brought to the United States in 1893 for the World's Columbian Exposition. Sultan Abdülhamid II donated fifty-one albums to the "National Library"[97] of the United States; at least some of them went to Chicago as part of the Ottoman display.[98] As propaganda prepared under imperial orders, the 1,819 photographs constitute a reliable record of the prevailing Ottoman self-image. They highlighted the beauty of the landscape, the grandeur of monuments (Byzantine and Ottoman, including examples from the nineteenth century), and the development of modern institutions (schools, factories, hospitals, and military establishments). Perhaps to correct the dominant Western view, images of "harem girls" and "backward occupations" were omitted.[99]

The Unofficial View: Muslim Intellectuals and Journalists at the Fairs

The Muslim intellectuals who reported on the fairs associated "progress" with the Western world. The willingness to adopt Western technology as a key to modernization dated back to the early nineteenth century. Napoleon himself had said that Egypt must be assimilated into Europe so that it could benefit from the "advantages of a perfect civilization." Similarly, the Arab scholar Rifa'a al-Tahtawi urged the lands of Islam "to pursue the foreign sciences, arts, and industries, whose perfection in Europe is a well-known and confirmed matter."[100] For al-Tahtawi, modern Europe, under the leadership of France, was the epitome of civilization, and the key to its superiority was the development of sciences.[101] Another scholar, Harayri, noted after visiting the 1867 fair that the "period of isolation and individuation is ended and everyone tries to learn from the others. Representatives of Muslim countries should attend [these fairs] so that they may examine the exhibits and learn what will benefit their countries."[102]

Several years later the Egyptian Mahmud 'Umar al-Bajuri focused on the sophisticated European machinery at the 1878 exposition."[103] In a poem occa-

sioned by the 1889 Paris exposition, another Egyptian, Muhammad Sharif Salim, mourned the past grandeur of the Arab world, celebrated the power of Europe, and voiced his love of progress and desire for a new Egypt.[104]

While the Egyptians admired the technical achievements of the Western world, they had doubts and questions about Western culture. Muhammad al-Muwaylihi, one of the first Egyptian novelists, set his novel al-Rihla al-thaniya (The second journey) in Paris during the 1900 exposition. The novel's theme was the problem of introducing European traditions to the East in a rush and through bad imitations. Western civilization had accomplished much, the novel suggested, but had created serious social problems; therefore the East should import Western technology but at the same time should defend itself against the colonialists and maintain the "patrimony."[105]

Muhammad Amin Fikri, a judge and scholar versed in both Arab classics and French legislation, analyzed the history of the theater section at the 1889 Paris exposition, wondering whether Western theater could respond to Egyptian social, moral, and aesthetic needs if women acted on the stage or were included in the audience. He decided that women's emancipation had already begun in Egypt and that Egypt should not be deprived of European-style theater.[106] In 1900, Ahmad Zaki, the director of the Translation Bureau of the Council of Ministers in Cairo, also examined the French theater in Paris from a moral, and especially a sexual, point of view. He concluded that the Comédie Française would be a "bad school for women," giving them too many ideas on intrigue and immorality.[107] In his critique of French society, then, he also expressed his desire to protect his own gender-based status.

Easterners responded enthusiastically to the unfamiliar sights at the European expositions. In 1878, Sadullah Efendi, a young Ottoman diplomat, admired the facades of the Trocadéro Palace with their beautiful columns; the museum and the concert hall; the "regular gardens," which separated the various sections of the exhibition; the viewing tower with its elevator (which he called makine, "machinery"); and especially the large fountain in front of the Trocadéro Palace. He described this fountain as "adorned with gilded sculptures of wild animals":

As one looks from the garden toward this high structure [the palace], one gets the impression that a blackbird with open wings is flying from the edge of the

pool to the exhibition Court. The bridge [Pont d'Iéna] is a paved "salon" decorated with garden benches. It is from there that one watches the life on the Seine River, which flows between the regular stone embankments as though through a marble channel.[108]

In 1889, the Egyptian writer Muhammad Tawfiq al-Bakri evoked a similar dreamy feeling by comparing Parisian buildings to renowned Islamic monuments from various regions: the large residential buildings of Paris were like the palace of Ghumdan in Yemen; the "salons," like the throne room of Chosroes at Ctesiphon; Parisian parks, like the Shi'ib Bawwan in Persia; bridges, like those of Khurrazad in Samarqand or al-Baradan in Baghdad; and palaces, like Mshatta.[109] Al-Bakri's readers knew these fabled places as the great achievements of Islamic civilization, not from firsthand experience but from legend and tradition. He and other writers were adding European accomplishments to this system of mythical references.[110]

The most celebrated landmark of the 1889 Paris exposition, the Eiffel Tower, fascinated Muslim observers. Al-Muwaylihi dedicated an entire chapter to it, calling it the Eighth Wonder.[111] Ahmad Zaki wrote enthusiastically in the guest book that the tower represented the intelligence of its engineer as well as the achievements of the French people.[112] To him the tower, with the light on its top, looked like a big candle. Al-Bakri, a Sufi sheik, thought it hid a lantern, "the red star of Suhayl."[113]

The fair in 1889 was memorable not only for such works of engineering but also for the extensive use of electricity. An anonymous editorial in the Ottoman newspaper Sabah described the major exhibition buildings at night, when the Trocadéro Palace appeared as if made of light, the fountain's waters flowed in a glowing cascade, and the illumination of the Eiffel Tower seemed the work of the skies:

The night view of the exhibition grounds is beyond one's capacity to describe. One stops in awe before a splendor seen nowhere in the world until now. There is no spot that is not flooded with light to dazzle the eye. As one sees these lights, which with marvelous mirror effects pour a gold dust on the exhibition buildings, one wants to believe that the world-illuminating sun is dispersing its power . . . [But] the honor of illuminating the nights of the Paris exhibition belongs to

the light of "electricity." If electric power did not exist, the exhibition grounds could not be illuminated as they are now. . . . It is estimated that the electricity illuminating the exhibition grounds could bring light to a city of 100,000 people.[114]

Halid Ziya, a prominent Turkish novelist, also grew emotional in describing the power of technology and electricity:

The EifFel Tower was a wonder of the time. One night, in an unexpected moment, when this iron tower three hundred meters tall was suddenly painted in red flames by an electric current, the thousands of people gathered beneath it unconsciously cried from their hearts in a startled, fearful voice.[115]

Other accounts of the 1889 exposition were more measured. The Ottoman writer Ahmed Mithat Efendi gave a comprehensive factual description, devoid of emotionalism. He first surveyed the fairgrounds and then guided the reader through various sections, focusing on the Eiffel Tower and the Galerie des Machines, both of which he described thoroughly. The parks, the gardens, and the overall planning of the exposition, "like an entire country . . . independent of the city of Paris," impressed him in their scale and their construction details and materials. The Ottoman presence here was limited to a small tobacco pavilion, which Ahmed Mithat referred to as a "lovely hut." He noted in passing the locations of other Islamic and foreign sections but did not discuss their architecture.[116]

Ahmed Mithat's attitude typifies that of the Turks who wrote about their visits to the international fairs; they did not analyze the differences between their culture and the representation of that culture abroad. Turkish newspapers described the Ottoman pavilions and products in news items without much interpretation. The Egyptians, in contrast, were deeply concerned about the image of their country. In 1889, Muhammad Sharif Salim argued that encapsulating Egypt in a café, stables (with animal drivers), and almées (dancing girls) meant deforming it.[117] In 1900 Ahmad Zaki criticized the absence of modern Egyptian industry, commerce, and intellectual life at the exposition, and he regretted the inclusion of the belly dancers.[118] These also distressed 'Isa,

the hero of Muhammad al-Muwaylihi's novel: on arriving in the Egyptian quarter, he and his friends were pleased to find the atmosphere of their native land and at first thought that Egypt was well represented—but only until the spectacle in the theater began. Then, embarrassed by the performance of two female dancers, they left in shame, determined never to return.[119] Their shame indicates the seriousness of their concern for the national image presented to the West. For them the eroticized and commercialized nature of the dance was a distortion of their culture.

The Ottoman and Egyptian visitors to the international fairs who wrote about their impressions were interested in Western civilization and what it could teach them about improving conditions at home. They shared with their governments the belief that European civilization meant progress and modernity. Nevertheless, their unofficial accounts differed from official publications, which treated the national displays as propaganda.

Back home a cynical third party disseminated its views on the fairs in local newspapers and magazines. The Istanbul-based satirical journal Diyojen published a social critique referring to the advertisements in Ottoman papers calling for products to be displayed at the 1873 exposition in Vienna: simple wooden toys, handcrafted in Eyüp, a humble quarter of Istanbul, would reveal the progress of industry; a liter of milk mixed with tap water would represent the high quality of services provided by the modernized municipal administration; and a veil would symbolize women's emancipation.[120] The satire implicitly compared Europe and the Ottoman Empire and raised the key issues of industrial development, social services, and the status of women.

The cultural images projected to international audiences at the universal expositions were sometimes carefully constructed representations of self-images and aspirations, but their impact was rarely "corrective." On the contrary, European stereotypes of the East and the notion of a clear-cut world order, as sketched by European powers, remained dominant.