AIDS, Gender, and Biomedical Discourse: Current Contests for Meaning

Paula A. Treichler

Introduction: AIDS and the Challenge to Semantic Imperialism

Colin Douglas's 1975 novel The Intern 's Tale (set in a teaching hospital in Edinburgh) savages virtually every aspect of modern academic medicine—including its rampant and unreflective sexism. The book betrays its satire at the end, however, when two of the interns, Campbell and his friend, Mac, hospitalized with hepatitis B, deduce that the source of their infection is that well-known villain, the sexually active, unmarried woman:

Campbell sat silent, with a ghastly sensation of falling and accelerating and knowing that the worst feeling was still to come. When it did it was a horrible realisation.

"Christ! It's bloody Maggie!"

"What is?" said Mac gently.

"Maggie. Spreading it. Giving us bloody hepatitis."

. . ."Christ yes. It all fits." . . .

"Listen," said Campbell. "This is nasty and I'm sorry but it's important. When you were stopping by with old Maggie, did you use . . . what you might call an obstructive method of contraception?"

"Nope," said Mac. "Bareback."

"Charming. Me too. . . . I didn't because she said something about just finishing a period."

"That's not true. Not that week anyway. But she's got something far wrong with her cycle. Always dripping."[1]

It is a commonplace of feminist scholarship to claim that medical discourse represents women's bodies as pathological and contaminated.[2] But as this fictional conversation suggests, these representations bear complex historical burdens. Contamination is certainly one feature of Woman here: Maggie—an unmarried nurse generally regarded as a readily compliant sexual object—is suddenly transformed into an unruly agent of disease, actively "spreading" hepatitis to her sexual partners, including many of the hospital's medical staff. As they compare notes, the interns find she has lied to them, passing off the symptoms of serious pathology as a routine female complaint: Her lie can only succeed, of course, because both interns are ready to attribute the signs of pathology to the expected vicissitudes of the female menstrual cycle.[3] Thus, Maggie, like women elsewhere in the book and elsewhere in the history of medicine, is not what she seems.[4] From the perspective of the interns, she has tricked them into the potentially fatal risk of having intercourse "bareback," without protective contraception. Maggie's sexuality infects them with the possibility of their own mortality; at the same time, they express no concern about hers. For she who appeared to be a victim is now revealed as a deeply duplicitous perpetrator, a mimic of the symptoms and illnesses of others: Her dupes are the interns, whose only crime was to behave like "real men."[5]

The language as well as the narrative itself enacts this judgment. The carrier of "bloody hepatitis" is herself called "bloody Maggie"; the adjective bloody , linking the carrier, or source, of the disease with the disease itself, suggests indeed that Maggie, not a virus, causes hepatitis: she who is infected is simultaneously both infectious (a state or condition) and infecting (an active agent of disease). The word bloody also doubles as a literal description of Maggie's offcycle bleeding and as a broader cultural epithet (in American English, fucking doubles in a similar way). The images of diseased blood and body fluid invoke a long tradition in scientific and medical writing (see Ludvik Fleck's account of the history of syphilis, for example, where "bad blood" was a central concept).[6] With respect to the medical construction of women's bodies, a final point here is that men are the constructors, women the constructed. Despite the attribution of active agency to Maggie as a source of pathology, it is only the two male interns, the physician-scientists, who actively bring mind and knowledge to bear upon the situation. They alone have the right to analyze the situation with an appropriately trained "clinical eye" and to engage in those key activities of privileged theorizing, diag-

nosis of the disease, and authoritative identification of its cause.[7] Heirs of an ancient medical legacy of semantic and gendered imperialism, they define Maggie without hesitation as "bloody" and "always dripping." No longer containable through cultural pressure or moral prescription, freely infecting man after man, the sexually active container must therefore be contained. Their words contain, but also silence her.[8]

This chapter is about the ways that words, or more precisely, discourse, enact and reinforce deeply entrenched, pervasive, and often conservative cultural "narratives" about gender; it is also about how words seek, ultimately, to contain and control women's unruly and "uncontainable" properties. I will focus my discussion, first, on constructions of gender in the biomedical discourse on AIDS and, second, on the reverberations of this discourse in other writing about gender and AIDS.[9] Why AIDS? Because the discourse on AIDS—recent but already voluminous—reenacts many of the semantic battles that have characterized relations between women and biomedical science for at least the last century. AIDS takes us to the heart of feminist inquiry (indeed, of all the "human sciences"), including the question of how sex and sexuality are constructed; it also demonstrates how language can give the illusion of control. In the case of AIDS, however, the epidemic disease is so deeply complex at this point that control is out of the question.

In 1981 the official history of AIDS as a clinically defined entity began. Involving at first a small number of sexually active gay men, AIDS rapidly shifted to involve a larger and more heterogeneous male population, homosexual and nonhomosexual; by mid-1982, people with AIDS included intravenous users of heroin (and other drugs) who shared needles; Haitians; hemophiliacs; and others who had received injected blood or blood products. By early 1983 a small number of women were also diagnosed with AIDS, evidently infected via intravenous drug use or transfusions with contaminated blood, and by mid-1983 via male sexual partners with AIDS. Shortly thereafter heterosexual men with AIDS were identified whose sexual partner(s) had been infected females, demonstrating that women could both infect and be infected with HIV, human immunodeficiency virus. By 1984 there were reports from some central African countries (later fully documented) that almost as many women there had AIDS as men. A relationship between women and AIDS has thus existed for most of the known lifespan of the disease.[10]

This relationship, however, presents us with a series of mysteries. First, given the scientifically documented diagnoses of women with AIDS, why was AIDS simply assumed by the medical and scientific com-

munity to be transmitted only by gay men? Second, given the skepticism toward established science and medicine fostered for two decades by feminist activism and scholarship, why have relatively few feminists challenged biomedical accounts of AIDS or, with the exception of some lesbian writers and activists, called for solidarity with the gay male community? Finally, above all, given the intense concern with the human body that any conceptualization of AIDS entails, how can we account for the striking silence, until very recently, on the topic of women in AIDS discourse (including biomedical journals, mainstream news publications, public health literature, women's magazines, and the gay and feminist press)? As noted above, the real and imagined links between women's bodies and disease—especially infectious and sexually transmitted disease—are many and complex, and have a history reaching back many centuries. This is a subject, then, with heavy baggage—and the bags are already packed. Yet women have repeatedly been told that this time they would not be traveling, that they would not need the bags. If they were in the airport at all, it was for someone else's flight.

In the fall of 1986 all this changed: The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta reclassified a significant number of "unexplained" AIDS cases as having been heterosexually transmitted to and from women.[11] The National Academy of Sciences/National Institute of Medicine issued a blue-ribbon report warning the nation that AIDS was heterosexually transmissible both to and from women and men, making an urgent call for nationwide health education.[12] United States Surgeon General C. Everett Koop held a press conference to announce that he, too, now viewed AIDS as a potential threat to every sexually active person and to advocate the immediate institution of explicit sex education for everyone more than eight years of age.[13] The World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed what many had suspected: AIDS was devastating the populations of at least four African countries, where half of those with AIDS are women. AIDS has now been reported in more than 100 countries around the world and is now considered a pandemic health problem of catastrophic proportions.[14] In the United States, infection with HIV is estimated by some to be increasing among heterosexually active women and men (while rates of infection among sexually active gay men appear to have leveled off, though new AIDS cases and deaths remain high). "Suddenly," proclaimed the cover story of U .S . News and World Report in January 1987, "the disease of them is the disease of us "; and "us" is represented graphically in the magazine by a young, white, urban professional man and woman, a problematic repre-

sentation to which I shall return.[15] The main point here is that the population of people with AIDS now unquestionably includes women who appear to have become infected exclusively by way of sexual contact with infected men.

So, what a surprise to find ourselves in midair over the Atlantic without even a toothbrush packed—let alone a barrier contraceptive. The mystery is: Why were women so unprepared? And why do they continue to take it so quietly?

The construction in the United States of AIDS as essentially a male-only, sexually transmitted disease depends upon the production and reproduction of gendered readings whose reasonings are so outlandish and speculative as to be dizzying. In turn, this "knowledge" of AIDS infection and who can catch it filters out counterevidence in a variety of ways, creating a cycle of invisibility in which women do not believe themselves vulnerable and therefore do not seek medical care or even confidential testing. Despite this clinical history, moreover, women with AIDS have not been readily identifiable in the scientific literature. The pie-shaped charts typically depict the classic 4-H "risk groups"—homosexuals, heroin addicts, hemophiliacs, and Haitians—plus their sex partners, gender often unspecified—plus "Other."[16] To those familiar with feminist theory of the last two decades, the placing of women with AIDS under the literal rubric of "Other" possesses considerable irony and resonates with the ongoing construction of otherness in the history of venereal disease.[17] But, beyond irony, such otherness is dangerous because it creates a category of invisibility and it muddles information, both for those who have been or are at risk and for those who are responsible for identifying AIDS and its multiple manifestations. Thus, even after information about AIDS was widespread, many women did not believe they were at risk. Even today, women who finally seek care from health professionals may not be properly diagnosed, either because they are simply not seen to be at risk (whatever their symptoms) or because they do not display the symptoms (defined by the natural history of the disease in gay men) that officially denote the presence of AIDS and ARC (AIDS-related complex). Women's invisibility is created in other unexpected ways: One New York City writer, having heard in 1987 that "heterosexuals" were now considered at risk for AIDS, quizzed his white, middle-class female acquaintances and reported in the New York Times Magazine not a case of AIDS (or HIV infection) among them; as a nurse at Brookdale Hospital in Brooklyn acerbically pointed out in a subsequent letter to the editor, the writer would have

compiled quite different statistics had he explored the populations of poor people—primarily black and Hispanic, but also white—in the area surrounding her hospital.[18] Such examples of women's invisibility in the AIDS discourse reinforce the widespread perception of AIDS as an illness of sexually active gay men and of illegal-drug users; it is based, then, on scientific constructions that have glossed over the "Other" despite growing evidence that the category includes women (and men) who have been infected with AIDS by way of heterosexual intercourse of the boy-meets-girl/missionary position/no-frills variety.[19]

AIDS is debilitating, lethal, and in many respects still mysterious; some authorities regard it as the greatest health crisis of our era. The scientific label AIDS is normally construed to refer to a real clinical syndrome, an infectious condition caused by a virus and increasingly understood by the scientists and physicians who study it. But the relationship between language and reality is highly problematic, for scientists and physicians as well as for "the rest of us." Although we have come to accept the findings of biomedical science as accurate characterizations of material reality, scientific and medical discourses are always provisional, and only "true" or "real" in certain specific ways—in confirming prior research findings, for example, or in promoting effective clinical treatments. "AIDS" does not merely label an illness caused by a virus. In part, the name constructs the illness and helps us make sense of it. We cannot, therefore, look through discourse to determine what AIDS "really" is. Rather, we must explore the place where such determinations occur: in discourse itself, which is inevitably marked by our struggles to represent what we think AIDS really is and to conceptualize what it really means.

To talk of AIDS as a linguistic construction is not, of course, to claim that it exists only in the mind. Like other phenomena, AIDS is real, and utterly indifferent to what we say about it. Documented by news reports, medical records, photographs and journals, scientific research, conferences, and individual and collective experience, something is happening that real people are dying of. Whatever we call it, however we think about or represent it, we cannot wish AIDS away. Our names and representations can nevertheless influence our cultural relationship to the disease and, indeed, its present and future course. Accordingly, we struggle in many fragmentary and often contradictory ways to grasp the true nature of AIDS; yet, finally, this is neither directly nor fully knowable. It may be tempting, even irresistible, to understand the epidemic as a temporary problem involving incomplete scientific and medical

knowledge—certainly many familiar cultural narratives encourage this view—and to presume that we will eventually be provided a scientific account of AIDS closer to its reality. Moreover, to speak of AIDS as a linguistic construction that acquires meaning only in relation to networks of given signifying practices may seem to be both politically and pragmatically dubious, like philosophizing in the middle of a war zone. But as I have argued elsewhere, making sense of AIDS compels us to address questions of signification and representation.[20] When we deduce from the facts that AIDS is an infectious, sexually transmitted disease syndrome caused by a virus, what is it we are making sense of? "Infection," "sexually transmitted," "disease," and "virus" are also linguistic constructs that generate meaning and simultaneously facilitate and constrain our ability to think and talk about material phenomena. Language is not a substitute for reality; it is how we know it. And if we do not know that , all the facts in the world will not help us.

AIDS and its related conditions present us with an unprecedentedly complex set of social and scientific problems. If we are to address these problems with foresight, intelligence, and decency, it is crucial that we take into account the nature of language and acknowledge AIDS's enormous power to generate meanings we can never fully control. This chapter seeks to illuminate the relationship of AIDS to gender through an analysis of language, meaning, and discourse; I use analytic strategies from the sociology of science, cultural studies, and feminist theory to review the evolving constructions of gender in AIDS discourse and examine how women are situated within that discourse. The chapter is organized, roughly, around the chronology of the AIDS crisis: (1) evolving biomedical understandings of AIDS (1981-1985); (2) Rock Hudson's illness and death as a turning point in national consciousness (July 1985-December 1986); (3) AIDS perceived as a pandemic disease to which sexually active heterosexuals are vulnerable (fall 1986-spring 1987); (4) diversification of discourse about women and AIDS (spring 1987-present); and (5) implications for the future.

Broadly, I seek to explain the paradox sketched above: When history, culture, and language link women to disease in many ways, why, until very recently, were these links to AIDS erased or denied? And now, finally included in the AIDS discourse, will women contest the meanings and implications offered by the past, refuse the scripts from the theater of history? I suggest that an uncompromising feminist analysis can contest the fixed notions of scientific certainty and disrupt the familiar cultural narratives. Where AIDS is concerned, for example, the entrenched

division between "them" and "us"—men and women, guilty and innocent, gay men and "the rest of us"—is deeply problematic. Based on simplified, unitary identities and essentialist biological or social categories that serve only to reinscribe conceptual and ideological divisions, the "us"—"them" division represents a form of semantic imperialism we cannot afford in the present crisis.

Purporting to describe the natural world, this division at first gave women the false belief they were invulnerable. But as evidence of women's potential risk became clear, so did the theoretical schisms in accounts of AIDS. This revelation should have demonstrated how tenuous the current conceptualizations are; it should have fundamentally challenged the validity of any division of "the disease of them" from "the disease of us." Yet most discourse by and about women embraces this division, simply rearranging the contents of the categories to match the latest bulletins from Washington, Atlanta, or Paris, and advising "us" (women) to protect ourselves from "them" (men). It does nothing to unseat the notion that "them" (whoever they are) is an expendable category of people, while "us" is a category of people worth saving. Despite all we have learned about the social construction of sexual difference and how it has been used against women in the past, the categorization process is given little scrutiny in the case of AIDS. By questioning, therefore, what is often taken for granted in discussions of AIDS, I hope to illuminate its multiple dimensions, intricacies, and contradictions, and, in doing so, to contribute toward the development of policies that fully acknowledge the intractable complexity of this crisis.

The Evolving Body of the Gendered "AIDS Patient" in Biomedical Discourse

The existence of AIDS as an official clinical syndrome is generally dated from the report of the deaths of five gay men in Los Angeles from Pneumocystis pneumonia in the June 5, 1981, issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR ), published by the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta. The paper, by Drs. Michael Gottlieb and Wayne Shandera of the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), had been routed in May by Dr. Mary Guinan to Dr. James W. Curran, head of the CDC's venereal disease division; he returned it to her with a note: "Hot stuff. Hot stuff."[21] Although Gottlieb had initially thought nothing of the fact that his first Pneumocystis patient was gay (he con-

sidered it equivalent to "the fact that the guy might drive a Ford"[22] ), he had decided by the time the paper was written that this was an outbreak of a new illness specific to gay men. The MMWR bulletin put it this way: "The occurrence of pneumocystosis in these 5 previously healthy individuals without a clinically apparent underlying immunodeficiency is unusual. The fact that these patients were all homosexuals suggests an association between some aspect of homosexual lifestyle or disease acquired through sexual contact and Pneumocystis pneumonia in this population."[23] The men who died from these first reported cases were not only gay, they had histories of multiple sexual contacts and of multiple sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). The published report confirmed the suspicions of physicians in other cities: Some of their gay patients were contracting and even dying from very strange diseases, including rare forms of pneumonia and cancer. What had been unofficially called "gay pneumonia" and "gay cancer" and WOGS (the Wrath of God Syndrome) now provisionally came to be called GRID: Gay-related immunodeficiency.

But in the months following the report in the MMWR and subsequently in other journals, these same rare diseases began to be diagnosed in people who were not gay—for example, in intravenous drug users, in hemophiliacs, and in people who had recently had blood transfusions. Despite widespread reluctance to acknowledge possible connections, there were enough nonhomosexual cases to render GRID an unsuitable diagnosis, and in 1982 the name "AIDS" was selected at a conference in Washington, D.C.[24] As it evolved during 1981 and 1982, the official CDC list of populations at risk for AIDS came to consist of the "4-H" group: homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroin addicts, and Haitians; by 1983 the sexual partners of people within these groups had been added.[25] This list structured the collection of evidence for the next several years and contributed to the view that the major risk factor in acquiring AIDS was being a particular kind of person rather than doing particular things.

Outside the narrow, controlled, official account were disturbing exceptions: reports that in Africa women and men were afflicted with AIDS in equal numbers, observations of babies with AIDS-like symptoms, rumors of AIDS in men who had never used drugs nor had sexual contact with other men, reports of lesbians with AIDS.[26] In retrospect, it makes a tidy story to identify the tensions, ambivalences, and contradictions of this period as something simple: scientific conservatism, homophobia, denial, politicians' fears. Certainly there were instances of

predictable reflex behavior: the Wall Street Journal , like many other publications, published nothing about AIDS until "innocent victims" could be identified.[27] Some representatives of the far right were quick to seize on AIDS as new proof of the evils of a world gone soft on pleasure, communism, or both.[28] The discourse of this period and comprehensive accounts published since then demonstrate the complexity of social responses to a conglomeration of mysterious symptoms and fatal illnesses not yet well conceptualized. This is by no means to deny the profound discrimination that existed then and continues today (to which I shall return) but is rather to emphasize that at this stage many important questions were going unanswered. The conflict and contradictions among gay men, among members of the medical and scientific communities, among government officials, among reporters—all of whom by turns perceived AIDS as a gay disease and then denied that it could be, predicted a spread of AIDS to other groups and then rejected such a possibility—might also be understood as part of the process of making sense of problematic and frightening evidence.[29] It is important for the future that the past not be oversimplified. Although Randy Shilts's comprehensive book on the AIDS crisis, And the Band Played On , for example, demonstrates many points at which bias against and fear of homosexuals hampered public attention and fundraising, Dennis Altman notes that had AIDS first struck intravenous drug users and Haitians rather than the politically sophisticated and well-organized gay community, funding and publicity would undoubtedly have been even more meager and delayed.[30] Policy analyst Sandra Panem, reviewing charges that homophobia delayed federal research efforts, concluded that prejudice against homosexuality per se would not have deterred ambitious scientists from initiating interesting and rewarding research projects. But ignorance, she suggests, does appear to have played a role, citing as evidence a 1984 observation by James W. Curran, by then head of the CDC's AIDS task force, that among scientists there is little widespread research interest in sexuality of any kind and "not much understanding of homosexuality." Indeed, Curran went on to say that many eminent scientists during these early years rejected the possibility that AIDS was an infectious disease because they had no idea how one man could transmit an infectious virus to another; through what orifice could such a virus possibly enter a male body, lacking as it did the vaginal portal approved for the receipt of sperm?[31]

The subsequent scientific and medical obsession with the details of male homosexual practices was in part a compensatory by-product, I

believe, of this dramatic ignorance among many scientists at the outset. But only in part: For a number of scientists and physicians first involved in AIDS were either gay or familiar with the gay community. Many CDC staff members had worked closely with the gay community in the course of research on hepatitis B and had few illusions about sexual practices and sexual diversity, and were aware that not all gay men were active with multiple partners. Further, as the infected population grew, it became clear that gay men were everywhere—in politics, in Congress, on Wall Street, in Hollywood, in far-right organizations. In many cases, they were silent and invisible—unlike women and racial minorities. Part of the shock of AIDS was thus the shock of identity.[32]

Whatever else it may be, however, AIDS in the United States came to be a story of gay men and a construction of a hypothetical male homosexual body. Obsession, a repeated feature of the AIDS story, is also a feature of the fact that, in some ways, the gay man is what Mary Poovey calls a "border case." A "border case" threatens a heavily invested binary division in society (such as the nineteenth-century dichotomy of women by class and how it was threatened by prostitutes) that generates the need for discourse to restore stability. (The voluminous discourse on prostitution during this period, Poovey argues, was thus fundamentally about class.)[33] The ongoing fixation with HIV testing is in part designed to put a stop to gay men's successful passing as straight; refusal to take the HIV-antibody test is therefore similar to pleading the Fifth.[34]

A number of hypotheses and speculations were put forward during this period about the nature of the AIDS epidemic: its dimensions, causes, newness, its theoretical, scientific, and political implications, and its consequences.[35] Despite lack of understanding, scientific and journalistic gatekeeping was evident from virtually the beginning—with one effect being the disinclination of editors and journals to suggest that AIDS was caused by an infectious agent.[36] When the first cases appeared in New York, Los Angeles, and Paris, the early hypotheses tended to be sociological, relating the disease directly to some feature of a supposed "gay male life-style." For example, in February 1982 it was hypothesized that a particular supply of amyl nitrate (or "poppers") might be contaminated. But "the poppers fable," writes French scientist Jacques Leibowitch, became "a Grimm fairy tale when the first cases of AIDS-without-poppers [were] discovered among homosexuals absolutely repelled by the smell of the product and among heterosexuals unfamiliar with even the words amyl nitrate or poppers ."[37] Another view was that sperm itself could destroy the immune system. "God's plan for

1. Steve Bell's satiric cartoon in the Guardian (16 October 1984, p. 29) links

"supply side" Reaganomics with its sexual analogue—a position embodied

nonsatirically in the deliberations of the Meese Commission for the Study of

Pornography (1984-1985). Courtesy of Steve Bell.

man," after all, said conservative Congressman William E. Dannemeyer (R. Calif.), "was for Adam and Eve and not Adam and Steve."[38] A cartoon in 1984 by Steve Bell in the London and Manchester Guardian satirized this position by showing Ronald Reagan declaiming from a podium in similar terms (fig. 1).[39] Women, this story goes, are the "natural" receptacles for male sperm. Their immune systems have evolved over the millennia to deal with these foreign invaders; men, not thus blessed by nature, become vulnerable to the "killer sperm" of other men. AIDS in the lay press became known as the "toxic-cock syndrome."[40] Note the contrast this latter view poses to the earlier one among some scientists that infection could be transmitted only from a penis to an "approved receptacle" (i.e., a vagina); now the "natural" receptacle is somehow seen as magically resistant to infection, while the orifices of the "guys with skirts" and the "AC /DC weirdos" become the preferred targets of killer sperm. (I discuss lesbians, the "gals in pants," below.)

Although scientists and physicians tended initially to define AIDS as a problem tied to gay culture, gay men on the whole also rejected the possibility that AIDS was a new, contagious disease. Not only could this make them sexual lepers, it didn't make sense: "How can a disease pick out gays?" they asked; it had to be "medical homophobia."[41] In the gay community, the first reaction to AIDS was disbelief. A gay physician in San Francisco told Frances FitzGerald: "A disease which killed only gay white men? It seemed unbelievable. . . . I used to teach epidemiology, and I had never heard of a disease that selective. I thought, they are

making this up. It can't be true. Or if there is such a disease, it must be the work of some government agency—the FBI or the CIA trying to kill us all."[42] In the San Francisco A .I .D .S . Show , one man is said to have learned of his diagnosis and then wired the CIA: "I HAVE AIDS. DO YOU HAVE AN ANTIDOTE?"[43]

Another explanation proposed in the early 1980s and still regarded as potentially significant is the notion that AIDS is a "multifactorial" condition. According to this view, no single infectious agent or other factor acts alone to cause the problem. Rather, a factor acts in conjunction with others. So-called cofactors range from the biological (e.g., various pathogens, including viruses) and biomedical (clinical history) to the social (poverty, diet), environmental (mosquitoes), psychological (guilt, stress), and spiritual (sin).[44] One hypothesis was that a person who is sexually active with multiple partners is exposed to a kind of bacterial/viral tidal wave that eventually crushes the immune system. Gay men on the sexual "fast track" would thus be particularly susceptible because of specific practices that maximize exposure to multiple pathogens.[45] Finally, a range of other possibilities has been proposed, from biological experimentation run amok to global conspiracy theories.[46] Yet the choice should not be seen as one between a single-agent theory and all other possibilities. With the growing complexity of the clinical and epidemiological picture (including the unpredictable relationship between exposure and infection, between infection and the development of clinical symptoms, and between the appearance of clinical symptoms and "AIDS") it seems, rather, that we should abandon the hope for finding a simple "cause of AIDS" and instead concentrate on making sense of what is already before us.[47]

Many were reluctant to move away from the view of AIDS as a "gay disease." For some, the name GRID would always shape their perceptions.[48] Yet what marked off the first years of AIDS from those that followed was the growing intensity of the search for an infectious agent—probably a virus—that could plausibly be implicated in the development of AIDS. Laboratories at the Pasteur Institut in Paris and at the National Cancer Institutes in the United States isolated a strain of virus that appeared to be associated with AIDS and AIDS-like conditions. I will not detail here the virus's story[49] but will say only that by the end of 1984 there was general consensus among many U.S. scientists that a virus was the major "cause" of AIDS.[50] "A virus," according to a story in National Geographic , "is a protein-covered bundle of genes containing instructions for making identical copies of itself. Pure information.

Because it lacks the basic machinery for reproduction, a virus is not, strictly speaking, even alive."[51] The virus is thus another "border case" that becomes the site—discursive and literal—for ongoing dispute.

Virologists and immunologists clearly considered the AIDS virus as extraordinarily interesting—a retrovirus , actually, that replicates "backwards," transferring genetic information from viral RNA (which becomes a template for transcription) into DNA. In turn, the DNA enters the cell's own chromosomes and, thus positioned within its infected host, may begin producing new viruses immediately or remain latent for years.[52] In the case of "the AIDS virus," now named "HIV" for human immunodeficiency virus, this dormancy can last up to (at present count) fourteen years, followed by a sudden explosion of replication that may kill the host cells (normally the helper T-cell—the conductor, it has been said, of the orchestra that is the immune system), leaving the host vulnerable to outside infections that a normal immune system would repel.[53]

The discovery of the virus by Dr. Robert C. Gallo and his research team was announced with great fanfare, and the promise of quick therapeutic measures was quickly issued by Margaret Heckler, then secretary of health and human services, who also said AIDS must and would be stopped before it spread to the "general population." For this she earned the title in the gay community of secretary of health and heterosexual services; the Reagan administration, for whatever reason, used the public outcry following the press conference as a rationale for reassigning Heckler to the post of ambassador to Ireland.[54] The incidence of AIDS in the gay community also increased, though more was becoming known about transmission, protection, and treatment. But the identification of the virus validated the authority of the Western biomedical research establishment and, as Donna Haraway suggests, enabled AIDS to be transformed from a low-status STD to the realm of High Science and High Theory. At the same time, the body was transformed from a mere combat zone to a communication, control & command center.[55] A virus, after all, is "pure information," and the body is simply the terrain on which it is transcribed.

The identification of the virus also, to some extent, put to rest so-called "spread of AIDS" stories.[56] Although the term virus did suggest possibilities of infection and contagion, the discovery nevertheless quickly acquired the status of a "fact" in scientific understandings of the illness and therefore fulfilled the functions of a "fact" as defined by Ludvik Fleck: "In the field of cognition, the signal of resistance opposing free,

arbitrary thinking is called a fact ."[57] So despite the appropriation of the virus as evidence to support many existing theories (e.g., the view that the CIA or KGB had caused AIDS), together with extant knowledge about viruses (e.g., that they cause colds, herpes, and polio), the overall effect was to concentrate speculation on modes of transmission and mechanisms of infection and destruction. Although sources of media coverage have increased and diversified since this period, particularly since late 1986, modes of representation (as suggested, for example, in a recent study of AIDS metaphors by Hughey, Norton, and Sullivan) have shifted as widespread uncertainty gave way to a better understood, if still greatly feared, illness.[58] In some cases, attempts to achieve certainty and to reduce public panic appeared to oversimplify the problem and to extend false reassurances. Other voices remained cautionary and careful, however, in assessing the data.[59]

As Jean L. Marx summarized the evidence in Science , "sexual intercourse both of the heterosexual and homosexual varieties is a major pathway of transmission."[60] Other articulate voices joined in warning about the public health consequences of treating AIDS as a "gay disease," and separating "those at risk" from the so-called general population.[61] Gary MacDonald, executive director of an AIDS organization in Washington, D.C., put it this way in 1985: "The moment may have arrived to desexualize this disease. AIDS is not a 'gay disease,' despite its epidemiology. Yet we homosexualize it, and by doing so end up posing the wrong questions. . . . AIDS is not transmitted because of who you are , but because of what you do ." MacDonald went on to note that almost a fifth of AIDS patients in the United States are intravenous drug users and another 6 percent never fit any of the high-risk groups. "By concentrating on gay and bisexual men, people are able to ignore the fact that this disease has been present in what has charmingly come to be called 'the general population' from the beginning . It was not spread from one of the other groups. It was there ."[62] As Ruth Bleier reminds us, questions shape answers. Thus, the question, "Why are all AIDS victims sexually active homosexual males?"—which has so dominated research—might more appropriately have been: "Are all AIDS victims sexually active homosexual males?"[63] But in quashing speculation and "hysteria" in the name of reason, expressions of scientific certainty also closed off considerations that women, nongay men, faithfully married couples, and so on could get AIDS. Statistical probabilities about what would happen were allowed to be read as theoretical constraints on what could happen.

Rock Hudson and the Crisis in Gender

Ironically, a major turning point in America's consciousness came in the summer of 1985 when Rock Hudson acknowledged he was being treated for AIDS.[64] Through an extraordinary conflation of texts, Rock Hudson's illness dramatized the possibility that the disease could spread to the "general population." "I thought AIDS was a gay disease," said a man interviewed by USA Today , "but if Rock Hudson can get it, anyone can." Hudson was, I would argue, another "border case" (in Poovey's sense) in which such textual conflations became common: When an event contradicts the perceived natural order of things, it becomes a cultural dispute that generates vast quantities of discourse designed to shore up existing distinctions and resolve contradictions.[65]

Another site of continuous dispute is the mechanism through which the virus is transmitted, as well as the different explanations for the epidemiological finding that AIDS and HIV infection in the United States were appearing predominantly in gay men. One view holds that the prevalence among the latter is essentially an artifact ("simple mathematics") because the virus, for whatever reason, infected gay men first and gay men tend to have sex with each other. The second is that biomedical/physiological factors make sexually active gay men and/or the "passive receiver" more infectable. A third view is that the virus can be transmitted to anyone, but that certain cofactors predispose the development of infection and/or clinical symptoms in particular individuals.[66] There are also speculations about the quantity of virus that is needed to cause infection (virus is both a count and a mass noun). Dr. Mathilde Krim, then of the AIDS Medical Foundation, for example, suggested that because the virus "must be virtually injected into the bloodstream" male-to-female transmission is more likely.[67] Jonathan Lieberson, likewise, concluded in 1986 that infection requires "direct transfusion into the bloodstream."[68] Dr. Jacques Leibowitch, however, relates transmission patterns, on the one hand, to the fact that homosexual men have sex with other homosexual men and, on the other hand, to the male homosexual "duality." A man, that is, can be a "receiver" of the virus from one man and then be a "donor" of the virus to another, in contrast to the "relative intransitivity of heterosexual propagation." By virtue of their "natural anatomy," women receive but do not give.[69] Indeed, many scientists have come to hold the view that, as Nathan Fain put it, "infection requires a jolt injected into the bloodstream, likely sev-

eral jolts over time, such as would occur with infected needles or semen. In both cases, needle and penis are the instruments of contagion."[70]

All this generated considerable confusion as to who was likely, even capable, of becoming infected and just what it was that increased or decreased that likelihood. Much of the uncertainty in the science and medical journals obviously turned (as, indeed, it still does) on the precise mechanisms of transmission. Nevertheless, even in the journal literature, and certainly as presented to the general public, questions about transmission were interpreted in part as questions—anxious questions—about sexual difference (male/female; heterosexual/homosexual; active/passive).

To the rescue came John Langone in the December 1985 issue of Discover magazine. In this lengthy review of research to date, Langone suggests that the virus enters the bloodstream by way of the "vulnerable anus" and the "fragile urethra." The "rugged vagina" (built to be abused by such blunt instruments as penises and small babies), in contrast, provides too tough a barrier for the AIDS virus to penetrate.[71] "Contrary to what you've heard," Langone concludes—echoing a fair amount of medical and scientific writing at the time—"AIDS isn't a threat to the vast majority of heterosexuals . . . . It is now—and is likely to remain—largely the fatal price one can pay for anal intercourse."[72] (This excerpt from the article also ran as the cover blurb.) Detailed cross-sectional drawings of anus, urethra, and vagina illustrated the article's conclusion.

The Discover article reassured many people about the continuing validity of the CDC's original 4-H list of high-risk categories. But categories of risk, of behavioral practice, and of identity may be quite distinct, or may overlap with each other—an ongoing problem in AIDS epidemiology and research. Sociologist Jeffrey Weeks, for example, analyzes the evolution of homosexuality as a coherent identity. "The gay identity," he writes, "is no more a product of nature than any other sexual identity. It has developed through a complex history of definition and self-definition," and "there is no necessary connection between sexual practices and sexual identity."[73] The problems with the CDC list were known to some science reporters, at least to the few who were knowledgeable and tenacious enough to take their analysis beyond the official party line. Ann Giudici Fettner, for example, pointed out in 1985 that "the CDC admits that at least 10 percent of AIDS sufferers are gay and use IV drugs. Yet they are automatically counted in the homosexual and bisexual men category, regardless of what might be known—or not known—about how they became infected."[74] So the "gay" nature of

AIDS was in part an artifact of the way data were collected and reported, though it was generally hypothesized until 1986 that the cases assigned to the category OTHER (or UNKNOWN, or UNCLASSIFIED) would ultimately turn out to be one of the four Hs. As Shaw and Paleo point out, however, the number of women in this category remains much larger than men; they point out, among other things, that the category "homosexual" was not broken down by sex despite potential risk for lesbians via sexual activity and artificial insemination.[75] Data from Africa were showing that women and men were infected in equal numbers; yet the practice of medicine and resources for data collection in Africa, especially outside urban areas, made the data questionable on a variety of grounds.[76] And even as evidence accumulated that transmission could be heterosexual (which begins with the letter H, after all), scientific and popular discourse continued to construct women as "inefficient" and "incompetent" transmitters of HIV, stolid barriers that impede the passage of the virus from brother to brother.[77]

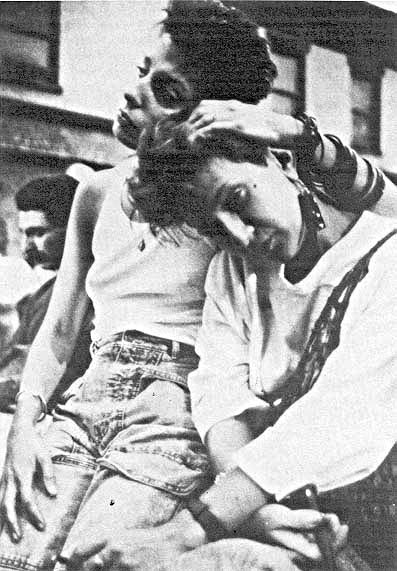

In the discourse of this period (from approximately mid-1985 to December 1986), there were exceptions, which will probably not surprise us. As evidence of AIDS in women mounted, speculation linked the disease to prostitutes, intravenous drug users, and women in the Third World (primarily Haiti and countries in central Africa). It was not that these three groups were synonymous but, rather, that their differentness of race, class, or national origin made speculation about transmission possible—unlike middle-class American feminists, for example. American feminists also by this point had considerable access to public forums from which to protest ways in which they were represented, while these other groups of women were, for all practical purposes, silenced categories so far as public or biomedical discourse was concerned (fig. 2).[78]

Prostitutes—despite their long-standing professional knowledge of STDs and continued activism about AIDS—have long been portrayed as so contaminated that their bodies are, like "bloody Maggie's" in the passage at the beginning of this chapter, "always dripping," virtual laboratory cultures for viral replication.[79] Early failures to find AIDS cases among prostitutes, however, supported the "gay disease" hypothesis.[80] "Women in general," concluded a Johns Hopkins professor of medicine, "seem to be less efficient transmitters of the disease."[81] Immunologist Paula Strickland concurred: "I think AIDS would be containable and would pose no threat to heterosexuals if there weren't any bisexuals in our society."[82]

Commitment to this view of AIDS as a male disease was so strong

2. Against a dark, ominous background, prostitutes are shown "working the

streets in New York." Despite many qualifiers in the caption and lack of

scientific evidence, Newsweek 's use of this photograph (12 August 1985,

p. 28) lent credibility to the familiar belief that prostitutes would inevitably

figure largely in the spread of AIDS. Courtesy of Ethan Hoffmann Archive.

that when R. R. Redfield and his colleagues reported a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association demonstrating infection in U.S. servicemen who claimed heterosexual contact only—with female prostitutes in Germany—various attempts were made to discredit or dismiss this new evidence:[83] Servicemen, for instance, would be punished for revealing homosexual behavior or intravenous drug use; they really had gone to male prostitutes, and so on.[84] If women were merely passive vessels without the efficient capacities of a projectile penis or syringe for "efficiently" shooting large quantities of the virus into another organism, the transmission to U.S. servicemen from German prostitutes must be only apparent. Indeed, one reader suggested, transmission was not really from women to men but was rather "quasihomosexual": Man A, infected with HIV, had sexual intercourse with a prostitute; she, "[performing] no more than perfunctory external cleansing between customers," then has intercourse with Man B; he is infected with the virus by way of Man A's semen still in the vagina of the prostitute.[85] It was taken for granted that the prostitute took no preventive or cleansing measures, and, one must suppose, that the projectile penis could also function as a kind of proboscis, sucking up quantities of virus from a contaminated pool. A similar metaphor, and one we shall meet again, occurs in a study of urban prostitutes in central Africa; the prostitutes are called "major reservoir of AIDS virus," African heterosexual males are "vectors of infection."[86]

Evidence suggests, however, that prostitutes are not at greater risk because they have multiple sex partners, but because they are likely to use intravenous drugs.[87] Shaw and Paleo, for example, write:

There is no evidence that prostitutes constitute a special risk category. . . . Some prostitutes do get AIDS. To the extent that researchers have been able to isolate prostitution and/or multiple sexual contacts from such issues as IV drug use, however, neither the number of sexual contacts nor the receipt of money . . . seems to put women at a higher risk for getting AIDS. Many women who are in paid sexual activity were concerned about sexually transmitted diseases even before the AIDS epidemic. They protected themselves and continue to protect themselves by being somewhat alert to new medical developments in sexually transmitted diseases and how to avoid them.[88]

COYOTE and other organizations of prostitutes have addressed the issue of AIDS rather aggressively for several years.[89] Some scientists have also attempted to counter the prevailing view that AIDS is predominantly and inherently a gay disease. Virologist William Haseltine, for example, dismisses exotic explanations of the African data: "To think that we're so different from people in the Congo is a more comfortable position, but it probably isn't so."[90] Haseltine successfully used this argument to obtain increased AIDS funding, citing Redfield's data on the U.S. servicemen in Germany at a congressional hearing: "These aren't homosexuals. These aren't drug abusers. These are normal, young guys who visited prostitutes. Half the prostitutes are infected, and these guys got infected."[91] Interestingly, he explicitly separates "normal, young guys" from gays and drug users, shifting in the last clause to the passive voice, a construction that reinforces their lack of culpability, representing them as innocent "receivers" of the infection, not problematic "donors." The "young guys" are the infectees, the prostitutes the infectors (compare this with the syntax of Shaw and Paleo, above, where prostitutes protect themselves and remain alert to medical news).[92]

A second exception were infected female intravenous drug users, or, as they are commonly called, "drug abusers" or "drug addicts" (though it is during use , not necessarily abuse , that transmission occurs).[93] Scientific and popular accounts have tended to show little interest in or sympathy for this group: It should be noted, however, that statistics are problematic in part because these individuals are hard to reach, and in part because drug use is compounded by other conditions. For example, HIV infection in prostitutes is often attributed to sexual contact with multiple partners (and especially to paying multiple partners), although, as I have noted, the sharing of needles in the course of intravenous drug

3. Live or stuffed animals in photos of persons with AIDS distinguish the "innocent"

from the "guilty," or at least normalize their "otherness." After Rock Hudson's death,

many publications ran sympathetic stories accompanied by photos of him playing with

his dogs: He had AIDS, ran the subtext, but he was still a good person. In early stories

on AIDS, researchers like the CDC's Jim Curran were often photographed with their

spouses and children: He may study AIDS, but he's as heterosexual as the next guy.

Photograph of Ryan White by Max Winter for Picture Group; photograph of Matthew

Kozup and his mother by Tim Dillon for USA Today . Both ran in Newsweek , 12 August

1985, p. 29.

use is the more likely source of exposure. Of the women with AIDS in New York City, for example, 62 percent are intravenous drug users and most of the others are sex partners of drug users; of the 183 cases of heterosexually transmitted AIDS, 88 percent were identified as sex partners of intravenous users, and fewer than 9 percent as the sex partners of bisexual males. Of the female HIV-positive prostitutes, almost all were intravenous drug users. Of the 156 children with AIDS as of December 1986, 80 percent had one or both parents who were intravenous drug users; the number of infected babies born at risk will rise each year.[94] In San Francisco, where a different epidemiological picture exists, transfusion-related AIDS is the most common source of infection for women; drug use and heterosexual contact come second.[95] Sex partners of "drug addicts," who, like transfusion cases, are often infected without their knowledge (even knowledge that their partner may be at risk for AIDS), are sympathetic "victims"—up to the point that they become

pregnant, when they become baby killers. Mothers with transfusion-caused AIDS remain sympathetic figures (fig. 3). But the CDC's James W. Curran in June 1986 pointed the finger directly at the "invidious transmission" made possible when female drug users and drug users' sex partners allow themselves to get pregnant.[96] With this act the passive receiver again becomes a culpable agent who transmits her infected blood "vertically" to her unborn child or (perhaps) after birth through breast milk. But as Shaw notes, little information is available about this phenomenon or about the effects of pregnancy on the woman herself; pregnant women may be both more likely to get infected if they are sexually active or, if already infected, pregnancy might activate the dormant virus.[97]

A third exception were women from central Africa and other areas of the world (primarily Haiti), where heterosexual transmission is more common. Again, no conceptually coherent explanation was offered for why a sexually transmitted illness should be homosexual in one country and heterosexual in another, although ad hoc speculations supported by virtually no documentation attribute the African statistics to "quasihomosexual" transmission of the kind noted above, refusal by African men to admit to homosexuality or drug use, the practice of anal intercourse as a method of birth control, or the widespread use of unsterilized needles in clinics and hospitals.[98] A debate in the letters column of the New York Times over the role of genital mutilation regarding AIDS in Africa illuminates the phantasmic projections of exotica that AIDS has stimulated. Fran P. Hosken suggested in December 1986 that widespread female "circumcision" (clitoridectomy and infibulation) is the main reason why the disease pattern is different in Africa (a 1: 1 ratio of women to men).[99] Douglas A. Feldman, acting executive director of the Queens AIDS Center, responded as follows: "Certainly, female genital mutilation is a brutal, sexist practice that should be strongly discouraged" but , he argued, the epidemiological pattern does not conform to the hypothesis of a relationship. In the countries where AIDS is widespread—Burundi, the Congo, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Zaire, and Zambia—clitoridectomies are rare. Where the procedure is common—from Senegal in the west to Somalia in the east—AIDS is generally not found. "However, as AIDS spreads into Kenya and eastern Tanzania, where the removal of the clitoris and labia majora is common, often resulting in genitourinary infections, it is likely that the practice may facilitate the spread of the disease." But after this potentially sensible comment—sensible because a history of infection is known to be rele-

vant to immune-system deficiencies—Feldman embarks on his own speculations, suggesting that the following factors may cause higher AIDS rates in African women: (1) higher rates of prior immunosuppression (but in relation to what? the infections he has just mentioned? poverty, malnutrition?); (2) intestinal parasite infestation; (3) greater likelihood of urban African women to engage in sex during menstruation (greater than rural women, or than American women? and is it yet established that this is relevant?); (4) "possibly the common practice by prepubescent girls in parts of central Africa of elongating the labia majora through continual stretching" (does this make it thin and "fragile" like the anal tract?); and (5) possible existence of an "immunosuppressive viral co-factor" (deuces wild). "But I fear," writes the doctor, "it is just a matter of time before the pattern of heterosexually transmitted AIDS in the singles bars along First Avenue, as well as the sidewalks of Queens Boulevard, will begin to look a lot like the pandemic in Africa today."[100]

This was December 1986, and suddenly the big news—cover stories for the major U.S. news magazines—was the grave danger of AIDS to heterosexuals. Major stories on AIDS as a threat to "all of us" appeared, for example, in Newsweek , U .S . News and World Report , Time , Scientific American , The Atlantic , and the Village Voice .[101] In a four-part series beginning March 19, 1987, the New York Times gave front-page coverage to several dimensions of AIDS; significantly, the boilerplate explanatory paragraph in each story made no mention of gay men or intravenous drug users. Although these groups were mentioned in the stories themselves, they were no longer considered intrinsic to the definition of AIDS.[102] No dramatic discoveries in the intervening year had changed the fundamental scientific conception of AIDS. What had changed was not "the facts" but the way they were now used to construct the AIDS text and the meanings we were now allowed—indeed, at last encouraged—to read from that text.

By the fall of 1986 virtually all theories of AIDS, no matter how remarkable their semantic underpinnings, had to confront the same bottom line: AIDS can be transmitted through heterosexual intercourse and other sexual activities to and from both women and men. It is important to emphasize that the gay community and (especially in New York City) the black and Hispanic communities continue to be most devastated by AIDS and most urgently in need of help. This does not mitigate the need to stress the possibility of widespread heterosexual transmission, and the current obsession with precise statistics—with

whether or not HIV infection is about to "explode" in the "general population," or with whether the entire epidemic itself is over—is, in my view, a dangerous diversion from questions of far greater importance.[103] My own concern continues to be with the evolution of "the facts," how these facts are constructed and represented, and, finally, how it has happened that the politically sophisticated feminist community has remained oblivious so long not simply to the potential risk to women but to AIDS as a massive social crisis.

AIDS Goes Heterosexual

Scientists commonly point out that AIDS arrived at the "right time"—that is, a time when basic science research in virology and immunology could provide a foundation for an intensive research effort on AIDS. They point out that no other epidemic disease has been analyzed so quickly nor its cause so efficiently determined."[104] Despite quarrels with this view (Randy Shilts, for example, calculates that the entire workforce assigned to AIDS was a tiny fraction of the one deployed to deal with the 1982 Tylenol scare in Illinois[105] ), let us concede that a number of biomedical researchers, epidemiologists, and clinicians have greatly contributed to our understanding of AIDS and that they were able to do so in part because of scientific progress in specific fields over the last twenty years. As Simon Watney points out, however, investigations of the last two decades provide a crucial foundation for the analysis of AIDS in the human sciences as well. Such a foundation prepares us to analyze AIDS in relation to questions of language, representation, the mobilization of cultural narratives, ideology, social and intellectual differences and hierarchies, binary divisions, interpretation, and contests for meaning.[106]

Models for such analyses in relation to AIDS have primarily been carried out by members of the gay community, whose interventions have helped shape the discourse on AIDS. As gay activists contested the terminology, meanings, and interpretations produced by scientific inquiry, loaded phrases like "promiscuous" soon gave way to more neutral behavioral descriptions like "sexually active with multiple partners" (many examples of such shifts are demonstrated in the collections of AIDS papers from Science and the Journal of the American Medical Association ). It is interesting that by 1986, when women were more central to the AIDS story, scientists and physicians were speaking of "sexually active" males and "promiscuous females."[107] Other linguistic

practices relevant to the construction of gender and sexuality in AIDS discourse are enumerated by J. Z. Grover.[108] Although such linguistic activism is dismissed by Shilts as misguided public relations efforts on the part of the gay community, it is more accurately seen, as Watney and others have argued, as part of a broad and crucially important resistance to the semantic imperialism of experts and professionals.[109] Challenging the authority of science and medicine—whose meanings are part of powerful and deeply entrenched social and historical codes—remains a significant and courageous action. It also provides an important model for women as evidence accumulates that neither gender nor sexual preference provides magical protection from the virus.

In 1985 and again in 1986 the CDC reviewed the patients who "could not be classified by recognized risk factors for AIDS." Eve K. Nichols, analyzing the CDC review of "unexplained cases" and related research, concludes that "these facts suggest a possible association between a small number of AIDS cases and heterosexual promiscuity in this country."[110] Despite the hedging and the use of the loaded term promiscuity , the conclusion represents a new biomedical construction of AIDS within the official scientific establishment. In December 1986 the CDC officially reclassified 571 cases formerly classified as "none of the above."[111]

What are biomedical scientists now saying about women? In April 1987 another article on women and AIDS appeared, this in the Journal of the American Medical Association .[112] Coauthors Mary Guinan, M.D., and Ann Hardy, Ph.D., M.P.H., review the 1,819 cases of AIDS in women officially reported in the United States between 1981 and 1986. Within the risk group of heterosexual contacts of persons at risk, the percentage of women increased from 12 percent to 26 percent between 1982 and 1986 (heterosexual contact is the only transmission category in which women at present outnumber men). More than 70 percent of women with AIDS are black or Hispanic; more than 80 percent are of childbearing age. As to the "portal of entry" for the virus, it is unclear what is going on and will probably continue to be unclear until we know the precise mechanism(s) of transmission. The distinction between anal versus vaginal "portals," according to Guinan and Hardy, is relevant only if HIV cannot pass through mucous membranes and thus requires broken skin or membranes. But this is still unknown, and "if the virus can pass through intact mucous membranes, the risk of transmission through the vagina or rectum may not be different."[113]

Though its cautionary and provisional stance is welcome, this article is problematic in several ways: First, the women in risk groups are given their "status" only by virtue of their sexual partners—the men they're connected to—not by virtue of their own sexual activities. This kind of assignment appears to constitute a return to an earlier system of sociological categorization, one perhaps not fully theorized in the current situation. Second, the source of infection is determined according to a hierarchy of factors, with sexual contact taking precedence over intravenous drug use and with no dual assignments occurring; in CDC studies, therefore, infection in prostitutes has typically been assigned to contact with multiple sex partners, even though other studies, as well as prostitutes themselves, assign the source of infection to intravenous drug use.[114] And finally, above all, the purpose of studying women, we are told, is twofold: first, to use incidence in women as a general index to heterosexual spread of the virus, and second, to identify women at risk and prevent "primary" infection in them in order to prevent the majority of cases of AIDS in children that would result from these maternal risk groups without intervention.[115] There is thus no intrinsic concern for women as women . Yet, because pregnancy suppresses the immune system, any woman who gets pregnant increases her risk of infection with HIV or, if already infected, possibly increases her risk of developing active AIDS.

It is true that we need to be concerned about "future generations." During the Venetian plague of 1630-1631, ten thousand pregnant women were killed in a period of months, decimating the city's childbearing population.[116] As Shaw and Paleo point out, because the widespread practice of safer sex would drastically reduce the birth rate, childbearing might come under intense scrutiny by the state, and women of childbearing age might be among the first groups to undergo mandatory testing.[117] But surely we are also concerned about women themselves and need to give thought, in policies and practice, to them rather than simply treating them as transparent carriers who house either the future of humanity or small Damiens who will assist in furthering viral replication.

In other biomedical discourse, as I have noted, some scientists and physicians (including William Haseltine, Mathilde Krim, Jean L. Marx, and Constance Wofsy) have for some time noted that HIV may be heterosexually transmitted to and from women; and suggest that despite the small number of cases, woman-to-woman transmission may

also be possible.[118] Because of the still-unanswered questions, these professionals emphasize caution until more is known. What about lesbians, who still figure only fitfully in the biomedical story? Lesbians appear in the abstract to be at relatively low risk for HIV infection—lesbians as a group have a very low incidence of sexually transmitted disease, although the medical literature does include isolated reports, often in letters to the editor, of HIV transmission by way of female-to-female sexual contact.[119] Despite these virtually nonexistent statistics, lesbians were lumped by the public with gay men and considered just as dangerous; although lesbians in many cities are now organizing blood drives, for example, earlier attempts to do so had been defeated by the public perception that lesbians were as likely to be infected as gay men because "AIDS is a gay disease."[120] Ironically, despite many lesbians' long-standing support for and solidarity with gay men on the AIDS question, and despite the time lesbians contribute to AIDS hotlines and task forces, very little "safer sex" literature, whether directed toward homosexuals or heterosexuals is designed specifically for women whose sexual contacts are with other women.

Concerns about women in the general press have also come relatively late in the AIDS crisis. An important exception is Cindy Patton's 1985 Sex and Germs , a social and political analysis of AIDS that addresses the growing connections among contamination phobia, erotophobia, and homophobia, and proposes an agenda for progressive action.[121] Also useful is the work of Ann Guidici Fettner, Katie Leishman, Marcia Pally, Nancy Stoller Shaw, and J. Z. Grover.[122] Important and informed questions about the politics of AIDS and the "risk group" mode of describing vulnerability to HIV have consistently been asked by, among others, Randy Shilts, Peg Byron, Wayne Barrett, Simon Watney, C. Carr, Larry Kramer, and Nancy Krieger.[123] These writers have been notable. Politically oriented prostitutes' organizations have also been vocal in addressing issues of AIDS as they relate to women—advocating not only individual prevention strategies but also government responsibility for assuring safe conditions in a service industry.[124] Though the subject of women and AIDS was regularly covered only by a few women writers—primarily in radical journals in New York, San Francisco, and London—by 1986 most women's magazines had run at least one "What Women Should Do" or "What Women Need to Know" article (e.g., Vogue , New Woman ), and by 1987 mainstream feminist journals and magazines including Ms . in the United States and Spare Rib in Great Britain were providing fairly regular coverage.[125] Still, as Marea Murray

had argued in a 1985 letter to Sojourner , some women, including lesbians, continued to perceive AIDS as a problem "the boys" had brought on themselves,[126] while heterosexual women were still tending to see AIDS as nothing to do with them or as something that "self-help" procedures would guard them against. Of course, in the absence of challenge or resistance, female roles in the AIDS story remained the traditional ones: loving mother, loyal spouse, wronged lover, philanthropic celebrity; one man with AIDS even attributed his apparent remission to "the Blessed Virgin" (figs. 4 and 5).[127] But even here a confusion was evident as to who was guilty, who innocent, who was an active agent of disease, who a victim.[128]

Why was there such resistance to acknowledging women's potential to acquire and transmit AIDS and to deal clinically with AIDS as a woman's illness? One reason is certainly denial: the sheer unthinkability of AIDS unleashed upon the entire world population because, then, as someone put it at the Paris International AIDS Conference in July 1986, "the sky's the limit." Semantic imperialism breaks down in the face of the virus's ability to replicate infinitely. Instead, there is hope that the virus will be able to be "contained" within the populations already infected—i.e., "saturating" the established high-risk groups but not spreading beyond them. Though millions would die, this is still a containable subtotal of the "general population."[129]

A second reason for resistance to the role women play in the transmission of AIDS involves the potential difficulty of feminizing AIDS at this stage, after so long an identification with gay men. Shilts notes resistance to initial reports of infants and children with AIDS because the name GRID "by definition" signified a "gay disease." Yet Shilts himself, whose own account of AIDS begins with the mysterious illness in central Africa of a Danish lesbian physician, nevertheless focuses more intensely on a sexually appetitive Canadian airline attendant, a gay man who came to be identified by the CDC as "Patient Zero." Of course, as soon as the advance publicity on Shilts's book went out, the New York Post 's headline blared: "THE MAN WHO GAVE US AIDS!"[130] Others have pointed out that there is no need for female representation in the AIDS saga because gay men are already substituting for them as the Contaminated Other. Conservative journals like Commentary preserve this place by putting forth clearly and repeatedly the thesis so boldly stated by Langone: "AIDS remains the price one pays for anal intercourse."[131] In addition, Simon Watney and Larry Kramer, among others, observe that the gay community provides most of the volunteer workforce on AIDS

4. Although cases of women with AIDS were reported early on, women rarely appeared in the

official AIDS story except in secondary and traditional roles as mates and caretakers. Maria

Hefner was prototypical: She knew her husband was homosexual, but love conquered all. They

made national news in January 1987 after they learned he had AIDS and sought to be married

in a religious ceremony in St. Patrick's Cathedral. Weekly World News (17 February 1987, p. 17)

shows "loving wife Maria" taking care of David "during the last days of his life."

5. A few months later, another wife in Weekly World News (12 May 1987) plays quite a different

part in the AIDS story. Ola Lindgren, a Swedish physician, is reported to have murdered her

husband with virus-laden tomato juice (there is little documentation that oral transmission of

HIV would accomplish this). A photo shows "sneaky" Lindgren smiling, while the story tells

us that this "lady doc" murdered "hubby with AIDS cocktail!" Here was evidence of a female

literally carrying the virus home and giving it to her innocent husband, who gets the tabloid

fate he deserves for having married an ambitious professional woman: an epitaph from

Madison Avenue.

hotlines and other AIDS projects; when public information or television films or advertisements suggest the spread of AIDS to new groups, the "worried well" jam the phone lines beyond the capability of volunteers to answer. There are thus pragmatic reasons, until new groups of volunteers can be enlisted and trained, not to exaggerate the risk to this larger group.[132]

A third reason, I believe, essentially involves a desperate and terrorized effort to control signification. Faced with the nexus of sex and death, its fragmentation into hundreds of allied discourses, the breakdown of coherent categories of sexual identity into postmodernist "bundles of practices," and finally the virus itself with its capacities for infinite replication, who would not resist the entry of Woman, carrying the heavy baggage with which history has equipped her. As historian Allan M. Brandt notes, venereal diseases have typically been assigned a female identity; he cites a number of posters designed for U.S. servicemen, which show the equation of women with venereal disease (in one widely disseminated poster from World War II, for example, a painted prostitute walks down the street, arm in arm between Hitler and Hirohito; the caption reads: "VD: THE WORST OF THESE").[133] In this book and elsewhere, Brandt argues that AIDS has followed the historical pattern of earlier sexually transmitted diseases in generating fears of casual contact, concerns about contagion, stigmatization of victims as agents of the disease, and a search for a "magic bullet." AIDS is not yet, however, a particularly feminized disease, perhaps because, thus far, gay men have served so well as the Contaminated Other. As I have observed elsewhere, HIV is often anthropomorphized as a secret agent, but so far the gender is that of James Bond, not Mata Hari.[134] So long as the virus is characterized as "pure information," belonging to the largely male domain of perfect codes and high theory, it may resist a feminine conceptualization.

We should be aware, however, that language is already traveling from the site of the "sexually active" gay male body to the "promiscuous" female body. Numerous metaphors appearing in newspapers and scientific journals are cited by communication researchers.[135] Water metaphors appearing in 1987 ("IV drug users are the hole in the dike to the general population," "prostitutes are reservoirs of disease," and the "moist, vulnerable mucous membranes" of the female sexual organs) are reminiscent of the gendered tropes of history identified by, for example, Emily Martin and Allan M. Brandt.[136] In the Weekly World News , crème de la crème of supermarket tabloids, a loyal wife who stands by her husband with AIDS contrasts sharply with a new role for

women: a wife—a physician—who adds an HIV-infected blood sample to her husband's tomato juice and, with apparent relish, watches him develop AIDS and die.[137] The film Fatal Attraction , recapitulating Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds , gives us a taste of the consequences of "promiscuity."[138] Meanwhile, biomedical journals record the saga of an "exotic virus" infecting "exotic" African female bodies; now we learn that like this "fragile" AIDS virus our female bodies are "fragile," too, not rugged and tough after all but penetrable, "moist and vulnerable," or riddled with cracks and potholes. Are we now to become the carriers of this epidemic, ruthlessly moving everywhere? Is the female body, in fact, meaning itself, contaminating everything with its reservoirs of possibility and death? Reservoirs breaking down and letting language flow out, uncontainable within definitions? Like the virus, wearing an innocent disguise, are we not double agents, in league with the enemy? The question is how to disrupt and renegotiate the powerful cultural narratives surrounding AIDS. Homophobia, racism, and sexism are inscribed within other discourses at a high level, and it is there that they must be disrupted and challenged.

This leads to a fourth reason for the ambiguous positioning of women in AIDS discourse: Our relative failure—as feminists and as women—to address the problem of AIDS in challenging, theoretically comprehensive, or politically meaningful ways. In a final section, I will suggest some problematic aspects of current AIDS discourse by and about women as well as some useful directions toward a more satisfactory feminist analysis.

Women and AIDS: Toward a Feminist Analysis

Any analysis of AIDS based on a faith in stable boundaries between risk groups ignores everything we know about the realities of human sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infection. It further ignores the growing presence of AIDS as a dominant factor in the social life of the twentieth century in behavior, in law, in policy, in education, in health-care coverage, and in virtually all other areas of experience which, sooner or later, will touch every citizen.

Unless feminists take a broader and more active role in articulating the nature and meaning of the AIDS crisis, what is in store? One answer is that we will not understand the potential consequences of our own everyday sexual behavior, and this, I think, goes for gay as well as

straight women. Sexually liberated from the hegemony of the magical projectile penis, we should not assume the absolute truth of the scientific hypothesis that an "injection" of the virus is the sine qua non of infection. Even if it turns out that a critical mass of HIV is a relevant factor, this may vary in individuals. More crucially, sexual practices vary enormously among gay women as among all other people, and some of these practices may facilitate HIV transmission.