Housing Types

Our image of urban housing is probably dominated by the brilliant photographs of late nineteenth-century social reformers, whose pictures of tenements carried a sober and depressing message to their contemporaries and to us today. Our imaginations tell us that most nineteenth-century, and early twentieth-century, urban people lived in gloomy two-room apartments. Our imaginations are only partly correct, however, and we must put our ideas into a proper social context, reasoning first from our own experiences, then from historical research on both family life and residential mobility.

First, our own experiences. Probably very few readers of this book have lived in only a single residence during their lifetime. I am lucky enough to know two such remarkable people, both of whom live in houses most Americans would happily accept. One is the granddaughter of the Norwegian immigrant who built the house: she is the third generation to live in it. Contrary to popular folklore, such people have always been unusual in the United States. Most Americans have lived in housing circumstances very much contingent on their own career and family needs. Finally, no matter how constricted by the costly housing market, most of us can expect to live in different housing circumstances as we age and as our needs and resources fluctuate. I grew up in a turn-of-the century suburb in a big house. During any college years, I lived in the bedroom of a boardinghouse. After I married, I lived in a small apartment, and moved to several different ones. Finally, I bought a house, the first of two, the location of each determined by work; residential amenities were determined first for a childless couple, and later for a family with children. Presumably, as I age my needs will change, and I fully expect to someday end up living and dying in a room the size of which I had when a child. At each stage of this very ordinary sequence of housing, I felt I had a form (if not quite substance) of housing superior to all others. As a child, I though apartments were dreadful; as a student, I thought suburban

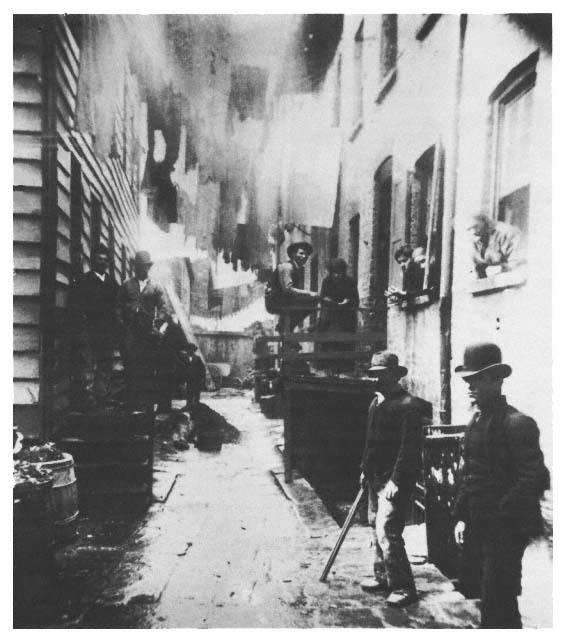

Bandits' Roost, New York (Jacob Riis), 1885.

This famous posed picture is supposed to show an overcrowded, sinister

slum. Alternatively, one could interpret it as showing a genuine community,

where neighbors chat and visit, and where communal standards of cleanliness

dictate that the laundry be done continuously.

Source: Museum of the City of New York.

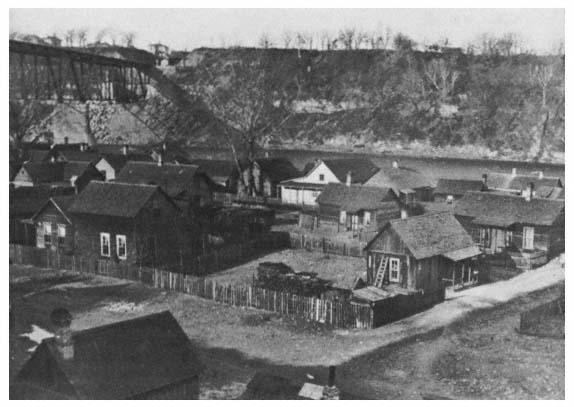

Bohemian Flats (Minneapolis), 1895.

With the Mississippi River in background, this late nineteenth-century

immigrant shantytown demonstrated the free standing single-family

homes possible for urban immigrants. Deprived of most city services,

the residents here still had a community church, gardens, access to the

river for fish and for wood (which floated by from lumber mills upstream).

Careful inspection shows that the unpainted houses had polished windows,

neat curtains, and an air of tidiness achieved only through hard work.

Source: M. Eva McIntyre photograph, Minneapolis History Collection, Minneapolis Public Library.

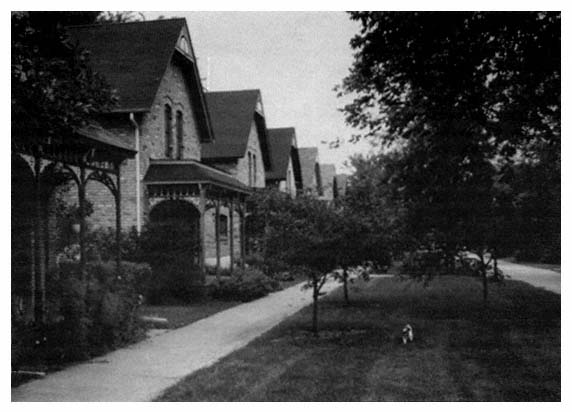

Milwaukee Avenue, 1987.

These small, free-standing houses, built for railroad workers in the late nineteenth century,

were bypassed by urban development until recent, very careful, restoration. Central air

conditioning, a street turned into a pedestrian mall, careful utilization of all existing interior

space, and far fewer persons per house turned housing for the working class into housing

for professionals. This successful conversion suggests how densely populated working class

and ethnic neighborhoods, like Bohemian Flats (preceding illustration), were they still standing,

might have fared as genteel and prestigious housing developments.

Source: photo by author.

lawns and home ownership too oppressive for words; right now there is no house too big for my desires; presumably when I am old all of my former houses will seem too inconvenient and troublesome. The point to this narrative is that the perception of housing quality is highly subjective, variable, and often narrowly rigid.

There is no objectively "good" housing form. In the late nineteenth century reformers were concerned with creating airy and light places. Why? Because they were still influenced by miasmal theories of disease; because most people had strong body odor; because heating and lighting equipment polluted; because the feeble artificial lighting made the urban world dim if not dark. Electric lights, steam heat, daily bathing, easily laundered polyester clothes, lead-free interior finishes, and cleansers without toxic and nasty smelling oils have made these concerns now only aesthetic. In fact, the well-ventilated and airy places so desirable a century ago are now stigmatized as drafty, poorly insulated, and unevenly illuminated.

While big cities did have tenements of the kind made famous by Jacob Riis's ominous view of New York's "Bandits' Roost," photographed in the mid-1880s, such rental apartments were not the only type of working-class urban housing. Detached, wood frame houses characterized far more the American urban house.[10] While New York tenements suffered from lack of ventilation, dampness, and unlighted rooms, more typical houses were simple wooden affairs, drafty, with no running water and outhouses for toilets. (A century later, these toilet pits are a goldmine for antique bottle hunters, who excavate them with an enthusiasm which would have been inconceivable to their previous inhabitants.) Their small yards had room for gardens, for chickens, perhaps for a cow or a pig. Relatively few of these wood frame houses have lasted into the late twentieth century, but their brick counterparts, built as workingclass housing, are enjoyed a renaissance as they are painstakingly restored by their latest round of owners.

Family historians have recently begun to use the concept of the life course, or family cycle, as a way of studying the family in the past.[11] They point out that needs, income, and expenditures vary as people move into different age-related roles, from children to single young adults, young married couples, families with growing and older children, families whose children have left, and older people. The old model of the nuclear family must be made more

dynamic. Historically, the average ages during various parts of the life course have changed, and the family's mode of coping with different parts of the life course have also changed. Clearly housing needs change with the life course. But in times not long past, housing and the life course had a very different pattern, and the change is due principally to the decreased size of families today and the movement of women into the workforce outside the home.

Today, women typically have careers outside the home which differ from men's mainly in that they are more interrupted by family care. Occupational opportunities have combined with, or perhaps even been driven by, much smaller family sizes, which have in turn reduced the amount of time a woman devotes to child care. In 1840, a woman with six children could have expected to be tied to the home for a minimum of eighteen years, so if her first child was born when she was twenty-five, she would not have been eligible to enter the outside work force until she was forty-two. Instead, she supplemented the family income by working in her home, taking in lodgers. Lodging was an essential part of a nineteenth-century family's income, with working-class as well as relatively affluent families taking in boarders throughout their lives. Single adults and often young families could expect to board with other families until they moved out and in turn took in their own boarders. Boarding did not end as a widespread practice until the post-World War I era, when it fell victim to social reformers' concerns about the presence of strange men in the homes of women whose husbands were at work, as well as to decreasing family size and increasing opportunities for women to work outside of the home. Until its demise, boarding meant, for women, that the home was a place of heavy labor. Carrying water up and down stairs for laundry, cooking, and household cleaning entailed toil every bit as demanding for women as what their husbands found outside the home.[12] Distance from water was far more important to these women than the light and airy rooms that housing reformers so loved to discuss. Thus we must temper the significance that we attach to our own housing standards when we apply them to the past.

Around the 1920s, then, the family's economic mode changed. Women worked less in the home and more outside the home, while at the same time the size of the nuclear family continued to decline. The average household—meaning the number of people who

occupied a housing unit, whether family, boarders, or other—was 5.8 in 1790, and has steadily dropped from 4.8 in 1900 to 2.8 in the 1980s. Perhaps more dramatic, 50 percent of households in 1790 numbered over 6; by 1950 only about 10 percent were so large. However, the age at which family formation begins has also dropped considerably. The median age at first marriage in 1890 was 26 for men, 22 for women; in 1970 it had dropped to 23 and 21 respectively. Probably one reason that the marriage age has dropped is the increased access to housing, both rental and owned, and the increased ease of acquiring mortgages. The long-term historical trend, then, is one toward shrinking yet also younger families, who are more able to obtain housing.[13]