Physical Characteristics

Most American cities are in a sense new towns and have the orderliness of new towns . They were laid out purposefully to house settlers coming from abroad or emigrating from east to west. Thus American cities often have a surveyor's clarity. By contrast, most European cities are organized more circumstantially in ways that reflect their origins in medieval agriculture and trade and betray subsequent necessities and events. Even those European cities that were laid out in neat grids by the Romans or as town plantations in the Middle Ages are sufficiently old to have lost the clarity of their original plans. The layering of subsequent centuries has altered and obscured earlier simplicity in European cities, so their patterns are less regular than those of newer American towns. This may account for the charming complexity Americans seem to appreciate when visiting Europe. Our towns do not have that quality yet. A comparison of Gloucester, England, and Austin, Texas, demonstrates. Both cities are based on a street grid. In the older one, however, that grid has been warped and modified by circumstances; in Austin, variation comes not through modification of the existing grid but in the way additions to it are handled.

Much of the urban design theory that values European piazzas, intimate

83.

The grid plan of Gloucester, England, established in Roman times, has

been softened by actions and events in the intervening centuries.

84.

Gloucester, circa 1800.

85.

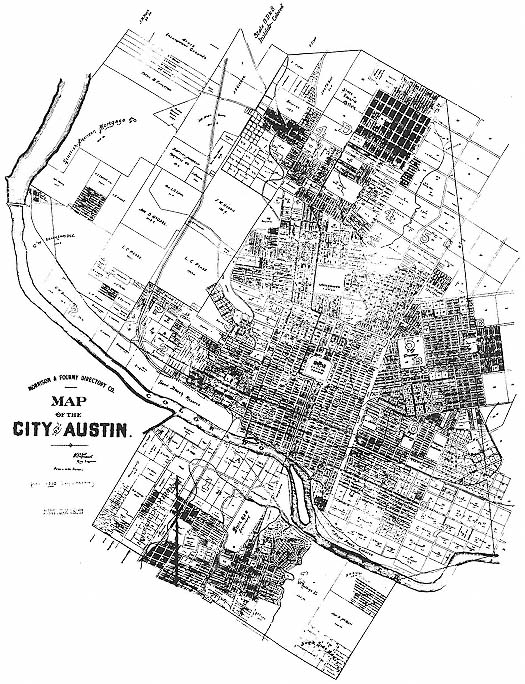

The grid plan of Austin, Texas (this one dated 1910), like many American grid plans, started out

perfect and then became distorted. Nonetheless the grid remains legible and undeniable.

86.

A European pattern of avenues, piazzas, and passages.

87.

Pattern of avenues, squares, and alleys, Sacramento.

passages, and bold axial boulevards slicing through the irregular texture of medieval cities is of questionable relevance to American circumstances and experience. Because the American urban pattern seldom has such characteristically medieval irregularities, it has not produced such transformations. American cities do have equivalent urban forms—square, avenue, alley—but these need to be understood on their own American terms, not as poor variations on European types.

Although it is sometimes criticized for monotony, the ubiquitous American grid has the virtues of clarity and flexibility; it can make form and circulation in a city comprehensible. Cities based overall on a grid pattern, however, often come to have a variegated patchwork pattern as a result of land development by subdivision, with individual developments reflecting varied visions, opportunities, and convictions. Although growth-by-subdivision is also a pattern to be found in European cities, it is a pronounced and typical American phenomenon. Within center cities a variety of land uses has been laid over the original grid, creating a smaller scale patchwork of districts: warehouse, Main Street retail, light industrial, nightlife, and so forth. The patchwork of American cities provides opportunities for diversity within the regularity of the overall circulation grid. Their juxtaposition creates legible boundaries defining

88.

A portion of Milwaukee shows how variegated subdivisions occur within the overall

structure of a regional street grid.

neighborhoods or districts. Thus an American city can be a collection of diverse rather than uniform parts held together by the underlying physical or conceptual order of the grid.

Streets are wide and straight in American cities. With the exception of Boston, Lower Manhattan, and other cities founded in the Colonial era, American towns are characterized by straight, broad avenues. This penchant for order was perhaps a reaction to the congestion of medieval European cities, perhaps a reflection of the spaciousness of the North American frontier. Certainly, simple patterns made real estate sales easier. Later, of course, the automobile gave a compelling reason for the American city to offer a commodious and clear system for circulation.

Accommodating the automobile can be a positive rather than a reluctantly provided or unplanned feature of American urbanism. Although street closures are sometimes warranted in redevelopment, more often vehicular streets are better used to frame and focus precincts of activity. Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, Michigan Avenue in Chicago, and Wisconsin Avenue in Milwaukee typify American streets as active urban places.

A hierarchy of highways, streets, and service alleys is a feature of many American towns. Regional arterials are substantially different from local streets. City blocks often are subdivided by narrow lanes for deliv-

89.

Wisconsin Avenue as a frame and edge to various developments in Milwaukee:

(1) the Grand Avenue extension, (2) Federal Building and Hyatt Hotel group, (3) the

Grand Avenue retail development, (4) riverwalk, (5) River Place, a mixed-use

development, and (6) Marine Bank (1961).

90.

Hierarchical street grid in Phoenix.

ering and removing goods. Whereas in nineteenth-century Paris, Baron Haussmann created a hierarchy of streets by carving out new boulevards from the existing fabric, in many American settings the hierarchy is inherent in the plan. Phoenix, for example, evidences the range: major arterials (at one-mile intervals), secondary arterials (at one-half-mile intervals), local streets, and midblock service alleys.

Whereas European cities typically were sited for convenience or security (a flat location and/or natural barriers as defensible edges), American cities often were simply a geometry imposed upon a map of a distant locale. Defense seldom was a concern in the way it was for Europeans; the shape of American cities comes not so much from an organic relation between inhabitants and settings as from the imposition of a pattern upon the landscape, often for profit-making purposes.

A consequence of this method of town making is striking deformations of the grid plan when it confronts natural terrain, as at Logan, Utah, and Los Angeles. In other cases the purity of the grid is distorted by human uses, for example, a rail line or the need for a market space. One might interpret such deformations as compromises, but in fact they are opportunities for enriching the urban experience and for creating diversity in land pattern and use in the context of the ubiquitous rational urban grid. The juxtaposition of two slightly different grids along a seam created by the Milwaukee River creates unique building sites, distinctive streets, and memorable vistas.

91.

Logan, Utah, where the grid is distorted by a river.

92.

Los Angeles, where the grid is distorted by topography.

93.

Reno, Nevada, where the grid is distorted by market functions along the

railroad as well as by topography.

94.

Vistas and view corridors that result from

the juxtaposition of grids along the

Milwaukee River.

The architectural character of American cities is as characteristic as the grid plan itself. A photograph of nearly any downtown or Main Street scene can readily be identified as American, for American cities look like American cities, not like Italian, English, or French cities. Our cities look as they do for several reasons: streets are straight and wide; antiquarian monuments are infrequent; buildings date from the nineteenth century or later; signs—literal and figurative—of commerce abound; and, most important, there is a grain and pattern to building development different from that of European cities. Denise Scott Brown caught the distinction in a study of Austin, Texas. The building patterns in Austin that she diagramed are in fact typical of many American cities.

In the United States, unlike Europe, individuated buildings usually make up the grain of towns and cities. Whereas freestanding buildings in Europe tend to be royal or religious institutions, in the United States

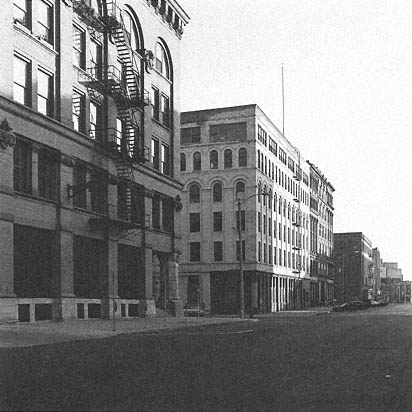

95.

Downtown Milwaukee as a recognizably American urban scene.

most public buildings have been deemed worthy of such monumental treatment. Monuments to the market economy, too—bank, department store, office building—have asserted their own importance by standing out and standing tall. In part this is a response to the grid that carves the urban fabric into so many uniform parts. It also evidences a competitive spirit and even good-natured posturing.

This pattern gives American cities a unique look and texture. The grain is coarser than that of old-world cities, and there are often more leftover open spaces than one would like. Although the danger in this development pattern is fragmentation, there is an opportunity to fill in residual spaces with other buildings, landscape features, walls, canopies, and other smaller-scale elements.

A counterpoint to individual freestanding buildings is evident in loft buildings that are generalized in function and merge to form tightly knit urban districts. Particularly in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, industrial and commercial lofts were developed with articulated urban street facades and large, open, undifferentiated interior spaces. These are strong urban buildings by virtue of their ability to define street space, and in many cities they offer opportunities for creative retrofitting.

96.

Denise Scott Brown's analysis of development patterns in Austin.

97.

Buildings along Michigan Avenue in Chicago demonstrate the tendency to stand

out, to differentiate themselves.

Earlier shopping and commercial buildings are a variant on such lofts and a recognizably American type. Stores on Main Street, U.S.A., are powerful in shaping the street but flexible, too, in accommodating activities. They can be refitted in various ways: they can be added together to make larger units; they can be reoriented to serve as modules within larger development concepts.

The styling of buildings, too, has taken its own course in the United States. Although classical, medieval, Renaissance, Georgian, Victorian, moderne , and other styles are found here, they receive uncharacteristic treatment in American hands. Hence Greek and Roman revival banks and government buildings have a recognizably American look. The neighborhoods of Georgetown would not be confused with analogous places in London. New York brownstones and San Francisco Victorians are distinctive architectural statements, whatever the sources. Main Street, U.S.A., does not look like High Street, England. The Chicago window is not found in Paris. The skyscraper has shown up only relatively recently in European cities.

Differences in the American experience give American urban design (and urban catalysis) a palette and an agenda different from those found in Europe, where an effort to create a sequence of urban squares, for instance, might be made possible by an intricate web of existing paths and neighborhood markets or similar open spaces. In North America such an effort would usually have to be created afresh and would probably fail because it would not be based on indigenous ingredients and traditions.

In most New World cities designers have another set of elements to work with. For example the undifferentiated and broad street pattern of U.S. cities offers a great opportunity to forge different kinds of streets in various parts of the city. Hierarchy can be created by changing the width and carrying capacity of streets, some emphasizing automobiles while others are zoned for increased pedestrian use. Such zoning implicitly changes the development patterns along the routes. Similarly, a "looseness" evident in the development of many American cities can be tightened by filling in and by inserting new uses in the underutilized centers of blocks, a procedure that would entail wholesale demolition in most European cities.

98.

Loft buildings, Milwaukee.