5—

The Emerging Character of American Cities

How are American cities different from most European cities, and how do those differences affect the ingredients and formulas for urban catalysis? By examining what has been built in America, we can find hints of what to look for in undertaking the generation and regeneration of American cities.

Inherent Opportunities

The assertion that American cities are physically different from most European cities is implicit in the preceding chapters. But how are they different, and what do the differences mean in shaping visions for future actions?

Physical Characteristics

Most American cities are in a sense new towns and have the orderliness of new towns . They were laid out purposefully to house settlers coming from abroad or emigrating from east to west. Thus American cities often have a surveyor's clarity. By contrast, most European cities are organized more circumstantially in ways that reflect their origins in medieval agriculture and trade and betray subsequent necessities and events. Even those European cities that were laid out in neat grids by the Romans or as town plantations in the Middle Ages are sufficiently old to have lost the clarity of their original plans. The layering of subsequent centuries has altered and obscured earlier simplicity in European cities, so their patterns are less regular than those of newer American towns. This may account for the charming complexity Americans seem to appreciate when visiting Europe. Our towns do not have that quality yet. A comparison of Gloucester, England, and Austin, Texas, demonstrates. Both cities are based on a street grid. In the older one, however, that grid has been warped and modified by circumstances; in Austin, variation comes not through modification of the existing grid but in the way additions to it are handled.

Much of the urban design theory that values European piazzas, intimate

83.

The grid plan of Gloucester, England, established in Roman times, has

been softened by actions and events in the intervening centuries.

84.

Gloucester, circa 1800.

85.

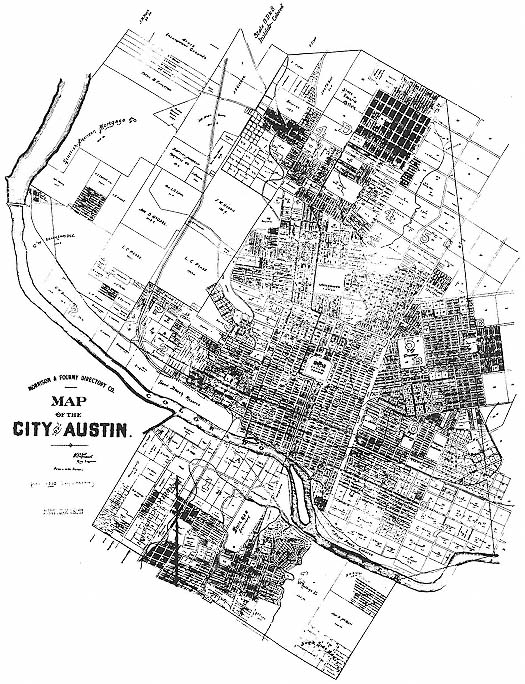

The grid plan of Austin, Texas (this one dated 1910), like many American grid plans, started out

perfect and then became distorted. Nonetheless the grid remains legible and undeniable.

86.

A European pattern of avenues, piazzas, and passages.

87.

Pattern of avenues, squares, and alleys, Sacramento.

passages, and bold axial boulevards slicing through the irregular texture of medieval cities is of questionable relevance to American circumstances and experience. Because the American urban pattern seldom has such characteristically medieval irregularities, it has not produced such transformations. American cities do have equivalent urban forms—square, avenue, alley—but these need to be understood on their own American terms, not as poor variations on European types.

Although it is sometimes criticized for monotony, the ubiquitous American grid has the virtues of clarity and flexibility; it can make form and circulation in a city comprehensible. Cities based overall on a grid pattern, however, often come to have a variegated patchwork pattern as a result of land development by subdivision, with individual developments reflecting varied visions, opportunities, and convictions. Although growth-by-subdivision is also a pattern to be found in European cities, it is a pronounced and typical American phenomenon. Within center cities a variety of land uses has been laid over the original grid, creating a smaller scale patchwork of districts: warehouse, Main Street retail, light industrial, nightlife, and so forth. The patchwork of American cities provides opportunities for diversity within the regularity of the overall circulation grid. Their juxtaposition creates legible boundaries defining

88.

A portion of Milwaukee shows how variegated subdivisions occur within the overall

structure of a regional street grid.

neighborhoods or districts. Thus an American city can be a collection of diverse rather than uniform parts held together by the underlying physical or conceptual order of the grid.

Streets are wide and straight in American cities. With the exception of Boston, Lower Manhattan, and other cities founded in the Colonial era, American towns are characterized by straight, broad avenues. This penchant for order was perhaps a reaction to the congestion of medieval European cities, perhaps a reflection of the spaciousness of the North American frontier. Certainly, simple patterns made real estate sales easier. Later, of course, the automobile gave a compelling reason for the American city to offer a commodious and clear system for circulation.

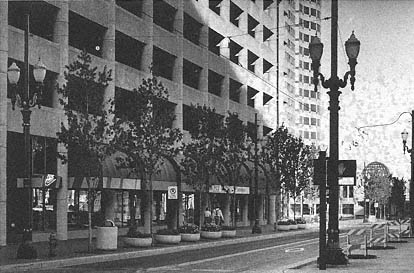

Accommodating the automobile can be a positive rather than a reluctantly provided or unplanned feature of American urbanism. Although street closures are sometimes warranted in redevelopment, more often vehicular streets are better used to frame and focus precincts of activity. Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, Michigan Avenue in Chicago, and Wisconsin Avenue in Milwaukee typify American streets as active urban places.

A hierarchy of highways, streets, and service alleys is a feature of many American towns. Regional arterials are substantially different from local streets. City blocks often are subdivided by narrow lanes for deliv-

89.

Wisconsin Avenue as a frame and edge to various developments in Milwaukee:

(1) the Grand Avenue extension, (2) Federal Building and Hyatt Hotel group, (3) the

Grand Avenue retail development, (4) riverwalk, (5) River Place, a mixed-use

development, and (6) Marine Bank (1961).

90.

Hierarchical street grid in Phoenix.

ering and removing goods. Whereas in nineteenth-century Paris, Baron Haussmann created a hierarchy of streets by carving out new boulevards from the existing fabric, in many American settings the hierarchy is inherent in the plan. Phoenix, for example, evidences the range: major arterials (at one-mile intervals), secondary arterials (at one-half-mile intervals), local streets, and midblock service alleys.

Whereas European cities typically were sited for convenience or security (a flat location and/or natural barriers as defensible edges), American cities often were simply a geometry imposed upon a map of a distant locale. Defense seldom was a concern in the way it was for Europeans; the shape of American cities comes not so much from an organic relation between inhabitants and settings as from the imposition of a pattern upon the landscape, often for profit-making purposes.

A consequence of this method of town making is striking deformations of the grid plan when it confronts natural terrain, as at Logan, Utah, and Los Angeles. In other cases the purity of the grid is distorted by human uses, for example, a rail line or the need for a market space. One might interpret such deformations as compromises, but in fact they are opportunities for enriching the urban experience and for creating diversity in land pattern and use in the context of the ubiquitous rational urban grid. The juxtaposition of two slightly different grids along a seam created by the Milwaukee River creates unique building sites, distinctive streets, and memorable vistas.

91.

Logan, Utah, where the grid is distorted by a river.

92.

Los Angeles, where the grid is distorted by topography.

93.

Reno, Nevada, where the grid is distorted by market functions along the

railroad as well as by topography.

94.

Vistas and view corridors that result from

the juxtaposition of grids along the

Milwaukee River.

The architectural character of American cities is as characteristic as the grid plan itself. A photograph of nearly any downtown or Main Street scene can readily be identified as American, for American cities look like American cities, not like Italian, English, or French cities. Our cities look as they do for several reasons: streets are straight and wide; antiquarian monuments are infrequent; buildings date from the nineteenth century or later; signs—literal and figurative—of commerce abound; and, most important, there is a grain and pattern to building development different from that of European cities. Denise Scott Brown caught the distinction in a study of Austin, Texas. The building patterns in Austin that she diagramed are in fact typical of many American cities.

In the United States, unlike Europe, individuated buildings usually make up the grain of towns and cities. Whereas freestanding buildings in Europe tend to be royal or religious institutions, in the United States

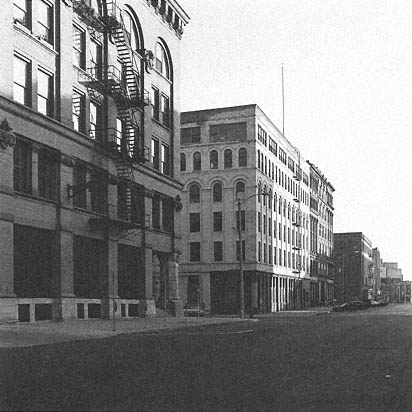

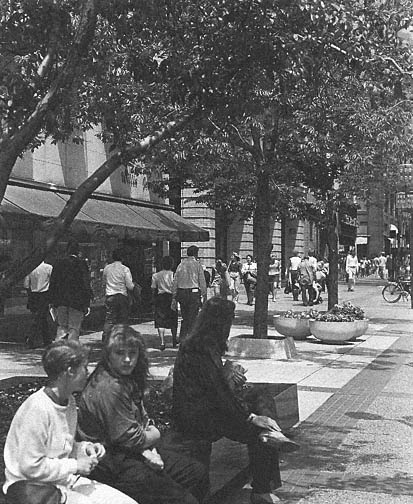

95.

Downtown Milwaukee as a recognizably American urban scene.

most public buildings have been deemed worthy of such monumental treatment. Monuments to the market economy, too—bank, department store, office building—have asserted their own importance by standing out and standing tall. In part this is a response to the grid that carves the urban fabric into so many uniform parts. It also evidences a competitive spirit and even good-natured posturing.

This pattern gives American cities a unique look and texture. The grain is coarser than that of old-world cities, and there are often more leftover open spaces than one would like. Although the danger in this development pattern is fragmentation, there is an opportunity to fill in residual spaces with other buildings, landscape features, walls, canopies, and other smaller-scale elements.

A counterpoint to individual freestanding buildings is evident in loft buildings that are generalized in function and merge to form tightly knit urban districts. Particularly in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, industrial and commercial lofts were developed with articulated urban street facades and large, open, undifferentiated interior spaces. These are strong urban buildings by virtue of their ability to define street space, and in many cities they offer opportunities for creative retrofitting.

96.

Denise Scott Brown's analysis of development patterns in Austin.

97.

Buildings along Michigan Avenue in Chicago demonstrate the tendency to stand

out, to differentiate themselves.

Earlier shopping and commercial buildings are a variant on such lofts and a recognizably American type. Stores on Main Street, U.S.A., are powerful in shaping the street but flexible, too, in accommodating activities. They can be refitted in various ways: they can be added together to make larger units; they can be reoriented to serve as modules within larger development concepts.

The styling of buildings, too, has taken its own course in the United States. Although classical, medieval, Renaissance, Georgian, Victorian, moderne , and other styles are found here, they receive uncharacteristic treatment in American hands. Hence Greek and Roman revival banks and government buildings have a recognizably American look. The neighborhoods of Georgetown would not be confused with analogous places in London. New York brownstones and San Francisco Victorians are distinctive architectural statements, whatever the sources. Main Street, U.S.A., does not look like High Street, England. The Chicago window is not found in Paris. The skyscraper has shown up only relatively recently in European cities.

Differences in the American experience give American urban design (and urban catalysis) a palette and an agenda different from those found in Europe, where an effort to create a sequence of urban squares, for instance, might be made possible by an intricate web of existing paths and neighborhood markets or similar open spaces. In North America such an effort would usually have to be created afresh and would probably fail because it would not be based on indigenous ingredients and traditions.

In most New World cities designers have another set of elements to work with. For example the undifferentiated and broad street pattern of U.S. cities offers a great opportunity to forge different kinds of streets in various parts of the city. Hierarchy can be created by changing the width and carrying capacity of streets, some emphasizing automobiles while others are zoned for increased pedestrian use. Such zoning implicitly changes the development patterns along the routes. Similarly, a "looseness" evident in the development of many American cities can be tightened by filling in and by inserting new uses in the underutilized centers of blocks, a procedure that would entail wholesale demolition in most European cities.

98.

Loft buildings, Milwaukee.

Political/Economic Opportunities

Physical differences are only part of the story. American cities also differ from European cities in the politics and economics of getting things done. Like the physical fabric of cities itself, the implementation of change and regeneration here is strikingly different from that in Europe. American cities have developed much more as the products of individual and external initiative than of local planning and control. For decades American cities could only stand by and watch as developers worked where they would. Then municipalities could only stand by and watch while federal bulldozers readied land for federally mandated change.

The movement toward giving the central government a greater role in development and redevelopment over the past two hundred years grew out of a perception that only through centralization could we deal with the complexities and scale of an urbanized, industrial society. Disillusionment followed when the costs of centralized organization proved to be high taxes and perceived waste and when problems meant to be solved persisted.[1] But now the partnership of private capital monitored and moderated by public interest offers an equation that seems to have more potential for improving the quality of urban design than earlier, largely private or largely public, mechanisms. There is increasing evidence that redevelopment works when guided by this alternative balance of power.

Partnerships between public and private interests seem well suited to the catalytic notion of urban design that we advocate. Private interests are concerned with marketability, with demand. Whereas affordability will temper development efforts almost anywhere, regardless of the economic or political system, marketability is a more typically American feature in development. Is there an existing market demand? Is there a potential market? Although urban design should not be shaped only by the market economy, realism about the market is necessary if catalytic development or redevelopment is to work. Developments do not succeed on virtue alone; market demand is necessary. A strong market, such as pent-up demand for office or manufacturing space or for housing, constitutes a potential for urban catalysis.

Concern for the Broader Public Good

Also suited to the catalytic concept is public concern about quality, costs, and benefits. How will people's lives be enhanced and the efficiency of the urban system improved? Will there be more or better jobs, social services, and housing? Uncontrolled and exploitative urban revitalization rarely produces such positive urban design. The boomtown growth of downtown Austin in the early 1980s exemplifies the phenomenon of land values rising not from need but on the expectation of future need. Raw market forces prevailed in Austin. Opportunities for an improved urban center were lost because sights were set only on profits. Of course master plans and various ordinances can affect "hot" real estate markets, but in most cities these controls at best only moderate excess. They do not necessarily mold positive, publicly beneficial urban design.

Both public and private interests recognize that development does not occur in isolation. There are both direct consequences and side effects. A recent and significant development in San Francisco makes the case. The demand for housing in San Francisco is such that almost any design scheme by Santa Fe Realty for its former railroad yards near downtown (called Mission Bay) could be an economic success, including speculative development to maximize a quick return. The planning and approval climate in San Francisco is stringent, however, requiring a development plan that fits the city and has the blessings of community groups in the area. The strength of the long-term demand encourages the developer to cooperate with the city in producing a plan that has widespread support,

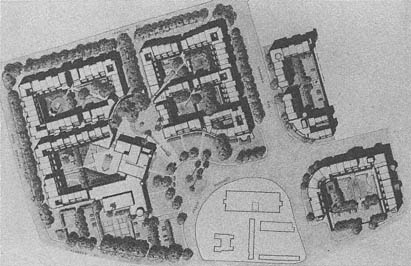

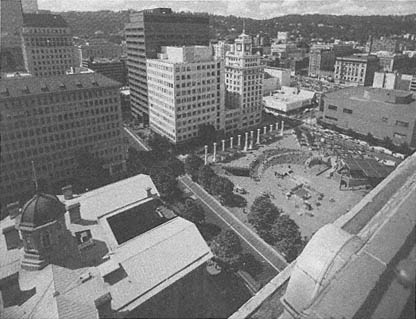

99.

Mission Bay development proposal, San Francisco.

even though it will take longer and cost more. Both sets of interests, public and private, recognize the importance of fitting the development carefully into the physical and social fabric of the city, of moderating and guiding its catalytic impact.

Mission Bay is an opportunity presented by pent-up demand coupled with public controls. Without these controls there is a danger of unmonitored change. The emergence of partnerships between municipal government and private development capital has created opportunities for revitalization that rival historic European partnerships of municipalities and church, trade groups, or national governments. Much redevelopment in European cities could not have occurred without the financial contributions of centralized institutions, first church, crown, and guilds and then central planning authorities. Similarly the redevelopment of American cities requires the involvement of major financing bodies, not as dictators but as an economic engine guided and controlled by broader public interests.

Proven Ingredients

American cities have produced a set of characteristic responses to opportunities for planning and development that constitute the ingredients available for revitalizing center cities. Although these ingredients are not necessarily original to America, most have been modified to suit American circumstances. In the catalog that follows, we identify obvious European roots. Our descriptions are intentionally terse because these ingre-

100.

A swatch out of an American fabric includes high-speed

regional movement, arterials, neighborhood streets and

service alleys, paths, rail lines, and even a canal.

101.

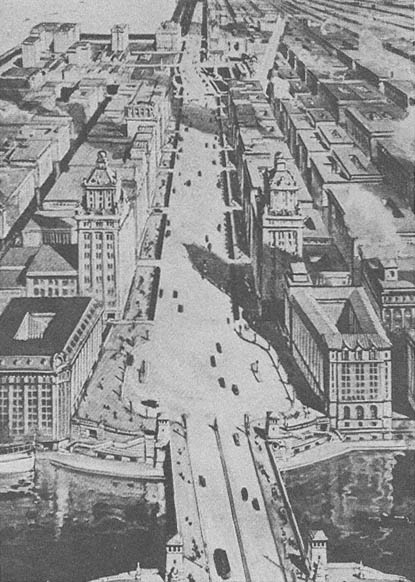

North Michigan Boulevard Extension, Chicago, 1920. From Chicago: The Great

Central Market, 1921. According to Michael Edgerton and Kenan Heise, in Chicago,

Center for Enterprise (Chicago: Windsor, 1982), property values increased by

$12 million after this transformation of what had been more modest streets.

dients can come to life only through their use by thoughtful designers responding to specific circumstances where catalysts, or support for catalysts, are needed.

Hierarchy of Movement

Although the principle of hierarchy of movement is established by European functionalist and systemic theory,

America's version of the idea is distinctive, perhaps because automobile use is so extensive and parking and access to parking have been a particular necessity. The hierarchy is efficient and workable. It admits the need for varied means and speeds of movement.

Boulevard

Because they are wider and operate as arterials, boulevards carry more traffic than typical streets. They are more pleasant to experience because of their planted median strips or verges or the tone of structures fronting them. Symbolically they lend status to addresses along the way or indicate a thoroughfare of special civic significance.

Main Street

Not surprisingly, urban elements that facilitate vehicular movement can also be places of pedestrian activity. Main Street is a major traffic artery, but it is a civic place, too. America's Main Street is a place to park a car while shopping or doing business. Teenagers cruise Main Street on Saturday night. Preservationists spruce it up to symbolize urban revitalization.

Suburban shopping centers tried to replace Main Street by offering a more palatable version that removed cars, provided shelter from the

102.

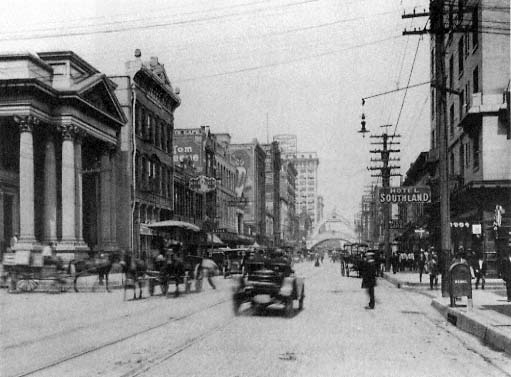

Main Street, Dallas, Texas, circa 1910. In Art Work of Dallas

(The Gravure Illustration Co., 1910), part 3.

103.

Portland Transit Mall, Skidmore Owings and Merrill, architects.

weather, and expunged references to labor and to classes other than the middle class. But this was not what was needed. What went wrong with Main Street was that as cities grew, it could not provide enough parking. Moreover, existing department stores on the main street were not large enough to survive, given contemporary retailing economics.

In response, the new version of Main Street provides convenient but unobtrusive parking, consolidates sizable retail space behind a collection of familiar facades, and mixes enough vehicles with pedestrians to give a feeling of street activity without jeopardizing safety. Discordant facades are not tamed with unifying graphics programs. Instead, vital variety is encouraged.

Transit Mall

The characteristic American problem of too many automobiles even for cities designed to facilitate automobile traffic has necessitated a customized solution to make public transit integral, attractive, and convenient. Buses and streetcars must not seem to intrude but to belong; pedestrians must feel at ease with them. Nicollet Mall in Minneapolis made the first strong case for such treatments. It proved that retailing, vehicles, and pedestrians could mix profitably through good design. A more recent example, Portland's Transit Mall, is conceived as one ingredient in the catalytic chain that is rejuvenating downtown Portland.

An economic analysis was performed to evaluate the feasibility of the [Portland Transit] Mall. The analysis identified and measured the direct benefits to transit users, and transit operating cost and safety savings, issues important to economists and planners to assess project feasibility. However, local decisionmakers and citizens are not particularly concerned with the aggregation of small savings

104.

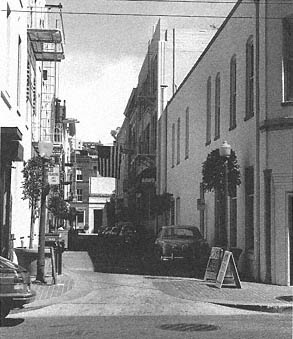

Multi-use alley in San Francisco's financial district.

of time, costs, or accidents. Rather, they are concerned with using transportation investments to maintain and strengthen the downtown area. Often investing in transportation is an expensive way to provide a competitive advantage. However, the Portland Mall has met the economic expectations well and is also extremely popular with citizens and politicians.[2]

Alley

That people and traffic can (and should) mix is a principle being explored in rethinking the role of alleys in American cities; similarly, the role of alleys solely for "service" is being rethought. Alleys add variety to the urban scene for pedestrians; they also have the potential for uses not feasible on more costly street frontage. In San Francisco's financial district, alleys are affordable sites for restaurants and office support services. (Grady Clay's book Alleys: A Hidden Resource describes the potential of alleys for improving the quality of American cities.)[3]

Skywalk

Humanistic and systemic designers in Europe called for "streets in the air" to facilitate neighboring in multi-family complexes as well as pedestrian movement in intensively developed parts of cities. The American version is skywalks that ease movement and ensure comfort in office and commercial districts. Cities like Minneapolis, St. Paul, Cincinnati, and, more recently, Des Moines and Milwaukee overlay the street grid with a pedestrian network that typically makes connections at mid-block. This pattern sometimes follows service alleys.

In most cases skywalks have been added to an existing urban fabric; a result is awkward connections where new bridges attach to older buildings. When skywalks are conceived as integral to buildings rather than as additions, the visual results are usually more pleasing.

One of the consequences of skywalks can be streets without pedestrians, for when foot traffic is elevated, and when developments are oriented to the interior of buildings, streets become the province only of vehicles. If streets are to remain "friendly," skywalks must be designed and access to them located to ensure continued use of the street level.

Riverwalk

River edges, a feature of many cities, are typified by three treatments: they are the "working" backs of buildings, providing utilitarian connections between river transport and riverside industry; they

105.

Skywalk system, Minneapolis.

106.

Paseo del Rio, San Antonio.

107.

The river and riverwalk create a separate pattern one level below downtown

San Antonio.

are formalized as pedestrian promenades (like the Embankment in London and the Seine embankments in Paris); they are naturalized as parks recalling an imagined idyllic character preceding urbanization (like Fairmont Park in Philadelphia).

America's preeminent riverwalk is San Antonio's Paseo del Rio. Although some of the building facades have been formalized, for the most part the back-side character of buildings was appreciated and accepted; all that needed to be done was to make the river's edge habitable and accessible. The result is a complex mix of buildings that formally address the river (like La Mansion Hotel, a former college) and less formal buildings that offer balconies and patios along the river.

In Milwaukee, developments downtown are stimulating renewed interest in pedestrian uses along the Milwaukee River. Riverwalk development, in turn, is supporting projects on abutting sites.

Promenade

In Europe pedestrian areas along grand boulevards and linear parks along streets change the act of getting from one place to another: these links between areas of activity themselves become destinations. That pedestrians mix with vehicles is not a detriment but a positive feature of such places, which "have always been like street theaters: they invite people to watch others, to stroll and browse, and to loiter."[4]

A promenade called the Rambla, modeled on Barcelona's Ramblas, is central to an urban design strategy for Austin, Texas, by Venturi, Rauch and Scott Brown: "Make Third Street both the main street and the public square of the project. We recommend the creation of an elongated, tree-lined pedestrian avenue [that] would be on the right-of-way of the soon-to-be-removed rail line along Third Street and would link Congress Avenue to Shoal Creek and thereby to the trails of Austin."[5] American designers need not look to Europe for such precedents. Brooklyn's Esplanade overlooking Manhattan "functions as a park, a viewing spot, and as a central anchoring space for the neighborhood. It feels as if Brooklyn Heights with its tight streets, were all one great building and the Esplanade were its veranda."[6]

Galleria

Although the name galleria has been appropriated for a wide variety of spaces and places, it originally referred to pedestrian streets under glass where the mix of activities associated with a commercial street is protected by a glass roof. Milan's Galleria is the model.

When the galleria appears in America,[7] it either takes over an existing street or creates an alternative place. The galleria of the Grand Avenue absorbs service alleys, and in concert with the existing interior of Plankinton Arcade, it forms an extensive, complex place. Similarly, a project called the Courtyards for Fort Wayne, Indiana, transformed a block of disparate retail units into a new complex with a glass-covered, three-storey passage along former service alleys. Kenneth Frampton pronounced the scheme an "astonishingly clever idea in relation to the disorganized, half-abandoned inner urban detritus that is being used, which has no order.

108.

The Rambla, proposed for downtown Austin by Venturi, Rauch and Scott Brown,

would establish a formal equivalent to a more typically American ad hoc version

of the promenade: the blocks of older buildings with restaurants, bars, and boutiques

along Sixth Street, not far away. The strolling, browsing,and watching characteristic

of Sixth Street could carry over to this redeveloped part of downtown.

109.

The proposed Rambla. Activities along the street are focused by the new promenade.

This introduction of an arcade system would revitalize the leftover bits, bond them together, and give them an internal life."[8]

Housing Precinct

The very term precinct suggests that a boundary or edge gives identity to a place; it also suggests a degree of security, the precinct's edge seeming defensible. Although walled compounds make poor neighbors, the desire for a sense of security must be recognized. It can be achieved by arranging housing and the passages around it to provide "eyes on the street."

The interior of a housing precinct is pedestrian oriented. Often it is raised above grade both to shelter parking and to demarcate the boundary. Shops located at grade serve a wider neighborhood as well as the housing precinct itself (see Figure 122).

Superblock

Because the ubiquitous American grid does not lend itself to all uses, development often needs to comprise a larger mesh. Milwaukee's Grand Avenue stretches across streets to create a linear shopping center paralleling Wisconsin Avenue. In Phoenix, developments encompassing six or more contiguous blocks will create building complexes around open interior spaces. Traffic flows around or enters the complex under strict control.

The advantages of assembling elements of the grid into larger blocks are efficiency and flexibility of use. A danger is that such complexes can interrupt the free movement of pedestrians or confuse a district's traffic patterns. In the past, parking podiums underlying such developments have too often created fortresslike obstructions to pedestrian movement. Then too, larger parcels can seem to justify the development of larger buildings; the combination can make a fine-grained neighborhood seem suddenly coarse.

110.

The Courtyards Development, Fort Wayne, Indiana. Eric R. Kuhne and Associates, 1985.

111.

The Courtyards Development, Fort Wayne.

112.

A housing precinct: La Entrada housing master plan, Tucson, Arizona,

ELS / Elbasani and Logan, architects.

113.

Superblock proposal for downtown Phoenix, Gruen Associates, architects.

Called superblocks, these urban elements parallel strongly Le Corbusier's notion, seen at Chandigarh in India, of pedestrian-oriented precincts within a network of roads and avenues. But in American usage they are not the underlying planning schema but are incidental, a way of drawing together or crystallizing particular areas of a city. The occasional overlaying of a larger mesh upon the grid creates welcome and often unexpected complexity within the otherwise rational and predictable urban pattern.

Pedestrian Mall

Simultaneously a goal and a place on the way to other goals, the pedestrian mall creates a realm where people on foot feel

114.

Kalamazoo Mall.

safe. Usually shops front on pedestrian malls. Associated housing is a supportive addition. Nearby parking and readily accessible public transport are crucial to keeping a mall occupied.

Regarding the success of Kalamazoo Mall over its first twenty years, a Downtown Kalamazoo Association representative concluded:

There has always been a total commitment by both the city and merchants to make the mall an attractive place to shop. There is a captive clientele of employees . . . at large businesses and institutions which ensure that a steady stream of people plies the auto-free streets. At least 75 percent of the mall stores are locally owned, a factor that guarantees a different attitude by shopkeepers and sales persons who deal with the shoppers. . . . [T]he Kalamazoo Mall was built in 1959 and as the first of its kind was early enough to attract the kind of clientele who stayed.[9]

Although for a time converting streets to malls was the most popular technique for center city redevelopment, pedestrian mall conversions do not always work. In many cases they have not brought about the anticipated retail rejuvenation—largely because they were conceived as single efforts rather than as part of a catalytic process—and the approach is less frequently used.

Positive Parking

Once the presence of automobiles is accepted as a given in American cities, provision for their storage should be handled not grudgingly but purposefully. Parking lots and, more pointedly, parking structures need to be designed as positive ingredients of the urban fabric and experience. Although the inclination to do little more than decorate parking structures is understandable, a more useful approach is to mix parking with retail businesses, offices, housing, parks, and so forth, domesticating the beasts, making them easier, more pleasant, to keep close at hand.

City Room (Interior)

Cities can have places where people gather and activities cluster in an urban mix sheltered from troublesome weather. A city room is not a pedestrian shopping street but rather a formal place that serves as a crossroads for varied activities. The Crystal Court at the IDS Center in Minneapolis embodies the idea. For Kalamazoo a more modest version at the crossroads of downtown serves similarly as a hub for hotel, shopping, restaurant, cinema, convention center, and office uses. It was conceived as the city's "living room."

115.

Morrison Park East parking structure, Portland, Oregon, tries to be a good neighbor.

116.

Crystal Court, IDS Center, Minneapolis, Johnson-Burgee, architects.

Photograph © 1986 Richard Payne, AIA.

City Room (Exterior)

Whereas the European square or piazza often grew from earlier marketplace activities, in America urban public spaces more often have formal origins as sites for courthouses and state capitols or as arcadian settings like grazing commons and landscaped parks. Outdoor urban "rooms" where people gather for informal activities were surprisingly rare in America until recent decades. According to the authors of A Pattern Language , in a "Public Outdoor Room,"

what is needed is a framework which is just enough defined so that people naturally tend to stop there; and so that curiosity naturally takes people there, and

117.

Pioneer Courthouse Square, Portland, Oregon, 1984,

Martin/Soderstrom/Matteson, architects.

Photograph © 1984 Strode Eckert Photographic.

118.

Invitation to a corporate drawing room, New York City. Park Avenue Plaza, by

Skidmore Owings and Merrill, architects.

Photograph by Joe Lengling.

119.

Redwood Park, San Francisco, which replaces a city street.

invites them to stay. Then, once community groups begin to gravitate toward this framework, there is a good chance that they will themselves, if they are permitted, create an environment which is appropriate to their activities.[10]

A recent example is Pioneer Courthouse Square in Portland, where formality and informality smoothly meld in a public place to which people are naturally attracted. The heart of Phoenix's Municipal Government Center will be a flexible city room.

Corporate Drawing Room (Corporate Atrium)

The private equivalent of the city room is the corporate atrium, a lobbylike place through which people are introduced to a building complex, a place that also serves as a semipublic urban amenity, a gift to the city. These atria are so numerous now that they constitute a coherent way of comprehending some urban centers. Publication of a "lobby and green space locater" guide to Midtown Manhattan testifies to the new pattern in New York; it is evident elsewhere as well.[11]

The type was established in America by the Ford Foundation building in New York City. Its proliferation and its tendency to create midblock linkages has produced pedestrian webs that belie the apparent regularity of the street grid. "Many [atria] have an entrance on one street and an exit on another, establishing a secondary, episodic pathway. New York's streets and avenues may seem strictly gridded and channeled, but the lobbies, in fact, make the city quite porous."[12]

Nature in the City

The purposeful provision of natural areas in city centers has been justified on the grounds of health and aesthetics, but it can also be argued for on social and economic grounds. Park or boulevard frontage increases land value; green spaces attract people and cause

120.

The Forecourt (Ira Keller) Fountain

(top) and the Lovejoy Fountain

(bottom), in conjunction with a small

park (center), create a pedestrian link

that unites sections of Portland.

121.

Site plan, Lovejoy Fountain. Lawrence Halprin, landscape architect.

them to linger. Early European examples of nature in the city were private squares associated with upper-class housing developments and public parks to provide relief from crowded living and working conditions. Corporate gardens and vest-pocket parks are recently introduced variations. The palette of design ideas for bringing nature into the city continues to broaden.

Fountain

Although in the past fountains have celebrated their practical purpose of making water available to a populace, more often they have no celebratory role and are included halfheartedly in the cityscape. Lawrence Halprin's fountains in Portland reinvigorated the impressive tradition of water as an urban element. They are not only ornaments but parts of a larger urban design strategy:

Right from the start, the Forecourt [Fountain] plays an important part in a sequence of open spaces—a matter of great importance to Halprin. This sequence starts in the adjoining Portland Center redevelopment project, where a system of planted pedestrian malls, also by Halprin, link[s] Lovejoy Plaza to Pettigrove Park—a cluster of shady green knolls—and continues to the auditorium.[13]

Microcosm

Conventionally called mixed-use developments, these complexes not only mix uses but blend them symbiotically. It is not enough to put housing adjacent to offices or to mix shops and convention facilities; the uses must reinforce each other. When the various ingredients of a mixed-use complex are related strategically to make them work the way a good city works, the complex becomes a microcosm of the city. Edmund Bacon argues that we should undertake such projects

because they intensify the richness of living, enhance people's range of experience and create easy access to a nearly inexhaustible variety of activities. Mixed

use developments are designed at a human scale and represent a positive attempt by the development community to achieve the public objective of keeping central cities alive and making cities a viable organism.[14]

Realm in Between

Although buildings-as-objects are a natural focus of urban design, there is also a peripheral area that is too often for-

122.

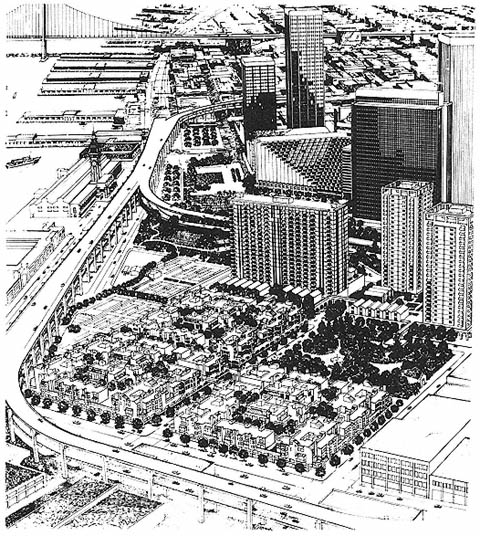

Embarcadero Center, Golden Gateway, and Golden Gateway Commons, San

Francisco. John Portman, Wurster Bernardi and Emmons, and

Fisher-Friedman, architects, designed various elements, 1962–1985.

123.

The Brewery, Milwaukee, a proposal for a mixed-use project incorporating the former Blatz Brewery,

Pabst Bottling Plant, other brick loft buildings, and new construction that in the end would provide

470 apartments, 300 hotel rooms, and 1 million square feet of offices, shops, and parking.

ELS / Elbasani and Logan, architects, 1978.

124.

In Kalamazoo, the areas behind the

Haymarket Historic District and

the areas between Bronson Park

and Kalamazoo Mall could become

realms in between other places.

gotten. Between the focal elements lie realms of less precise character that nonetheless have immense potential. Between the civic center and the pedestrian mall in Kalamazoo, for example, are pedestrian passages that potentially can offer an alternative location to the commercial activities on the pedestrian mall and an informal alternative to the civic park nearby. Similarly, between the formal Haymarket historical buildings and adjacent open space is an informal realm suited to more modest commercial uses.

Pocket of the Past

Groups of older buildings with a particular character can give parts of a city individuality and character. "Historic district" is more than a bureaucratic designation; it is a promise of character and visual interest. The economic incentives for preservation created in the 1960s and 1970s slowed demolition long enough for it to be proved that pockets of the past are not an urban liability but a versatile and attractive resource. In Portland's downtown the Yamhill and Skidmore districts are crucial elements of the overall revitalization strategy, as Figure 76 indicates.

Designated-Use District

Arts districts, cultural districts, educational districts, and so forth are all areas in which particular uses benefit from proximity to one another and where the concentration of these similar uses gives an area of the city a special flavor. Unique precincts with distinctive patterns of use (Sundays, late night, early evening, and so on) provide the satisfying variety needed in a healthy city. Theater districts in Milwaukee and Portland exemplify the pattern (see Figures 33, 82).

City Stoop

A stoop lets people sit and watch the city go by. A cascade of steps (the Spanish Steps, Rome; the Opera House steps, Stockholm; the New York Public Library steps) invites large numbers of them to observe the passing scene. It is not surprising that Martin/Soderstrom/Matteson's Portland Square design includes a substantial city stoop.

Colonnade/Arcade

Like many other elements of urban design, the colonnade, or arcade, grew out of a practical need but developed the power to mold urban character. In Southern Europe it shelters shops from the sun, and pedestrians (and casual business and socializing) from both sun and rain. Besides serving its practical purpose, it has achieved another end, giving continuity and character to urban settings. In Pasadena a colonnade was proposed to organize a collection of uses and diverse buildings, in fact to draw together several city blocks into a coherent, identifiable complex. A gesture of this magnitude seems in keeping with Pasadena's powerful city hall (glimpsed at the bottom of Figure 126).

125.

Portland's Pioneer Courthouse Square with its "stoop"

in use. Martin/Soderstrom/Matteson, architects, 1984.

126.

A design proposal for Plaza las Fuentes, Pasadena, California, by Moore/Ruble/Yudell, architects

and planners; Lawrence Halprin, landscape architect; and Barton Myers Associates, architects, 1985.

Furnished Street

Whereas life on the streets of European cities grows from necessity (daily shopping, moving between public transport and work or home, meeting friends), street life in American cities is largely voluntary and much more passive. As a result, American designers work hard to make the street environment comfortable and respectable—almost like home—with places to sit, handy trash receptacles, flowers and trees, good lighting, and an overall sense of design coordination. The American view is that people at leisure will enjoy watching others who are not. Part of the success of street conversions like Nicollet Mall (Figure 127) is attributable to the quality of its furnishings.

127.

Nicollet Mall, Minneapolis, Lawrence Halprin, landscape architect.

Photograph by Lawrence W. Speck.

128.

Chicago's Water Tower celebrates public works, identifies its district, and

ornaments Michigan Avenue.

129.

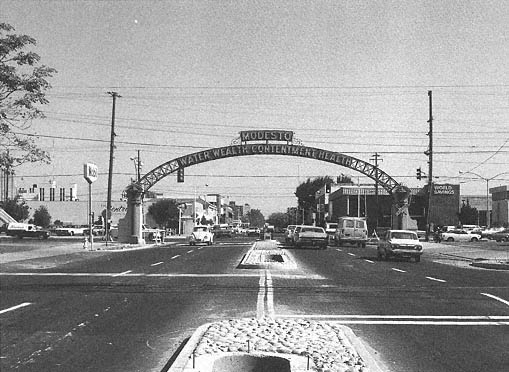

Typically, gateway arches have been more promotional than celebratory, but nonetheless they

give scale and lend a sense of significance.

Monument

Monuments celebrate heroes, civic services, and cultural achievements. Water towers in Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Louis, and Louisville are nineteenth-century celebrations of public water supplies. A twentieth-century equivalent is a Boston water tank transformed into a canvas for art. The State Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Indianapolis is intrinsic to that city's identity. From a utilitarian standpoint, monuments are landmarks, too, identifying districts and helping us stay oriented.

At another scale, markers of the skyline, like Philadelphia's and Milwaukee's city halls, are collective symbols. And though sometimes controversial, office buildings too can become, like the Empire State Building, the Transamerica headquarters, and the Sears tower, integral parts of a city's visual image. Skytowers, with their revolving restaurants and observation decks, are the latest urban monument in America. Gateway arches of an earlier era were more promotional than celebratory, but because of their location and size, they achieved the goal of bringing monuments close to daily life (Figure 129).

Design Guidance

Even though American cities are ripe with opportunities and proven ingredients for revitalization abound, productive catalysis depends on another factor as well: control. On its own, the physical form of a building or urban development can influence the form of adjacent developments, but the chance of a positive catalytic impact is not sufficiently dependable to suffice as an urban design strategy. Chance is not enough. Furthermore, typical zoning and land use controls do not go far enough to guarantee architectural quality or design coherence in new developments.

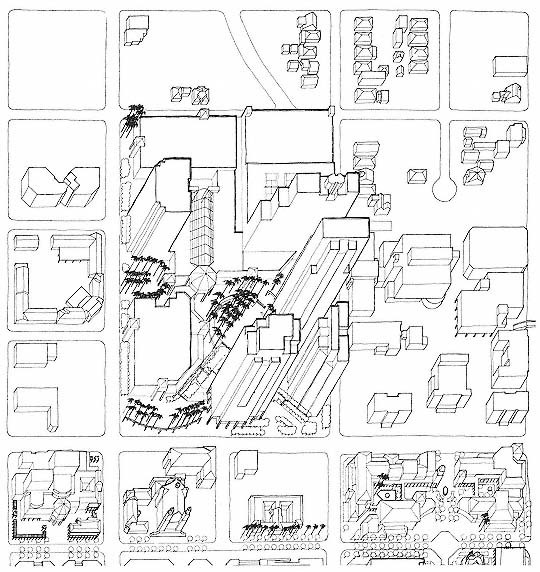

There are, however, increasing numbers of sophisticated extrapolations of zoning laws beginning to enhance and support the idea of the urban catalyst. It is beyond the scope of this book to describe specific ordinances and controls that have been developed by various cities. The following taxonomy of controls is intended to identify those that can build catalytic change in architecture and urban design. To explain these varied approaches to control, we use entries to the competition for the Phoenix Municipal Government Center Master Plan and the San Francisco Downtown Plan.

The urban design challenge in Phoenix was to formulate an architectural and urban pattern that would respond to environmental conditions and local history and thus become a guide for design elsewhere in downtown Phoenix. The complex also needed to be sufficiently vivid to give Phoenix a recognizable urban symbol. In San Francisco the objectives were to make downtown livable and the skyline appropriate, "to return to the complex visual imagery of the surrounding hillsides and to the complex architectural qualities of older San Francisco buildings."[15]

Conceptual Control

Controlling urban catalysis without repressing it depends on a thoughtful choice of concepts. Is a new use district—

130.

"Classical planning principles" in the Hartford Design Group / Tai Soo Kim proposal

for Phoenix. Crossed axes link significant urban elements (State Capitol and Convention

Center, railroad station and a church complex). The crossing is broadened to create the

municipal center.

131.

Arata Isozaki's Phoenix Garden and city-axis concept for Phoenix. A civic axis stretching

from the Convention Center to the State Capitol bisects a walled precinct, an urban room,

and a symbolic centercity desert: "In contrast with the other open spaces covered with

green, Phoenix Garden is a dry garden, a desert landscape . . . a perfect setting for a

sculptural court."

for example, a government center—better conceived as a separate entity, as an extension of downtown, or as a link between other use districts? What physical feature is the best conceptual guide for development?

The Hartford Design Group's concept for Phoenix was based on "classical planning principles," a public space/node at the crossing of two axes that linked public and semipublic realms. Downtown would orient to two specific axes instead of to the otherwise largely undifferentiated grid. Arata Isozaki's concept was a "city garden," an enclosed desert in the heart of the city sited along a vivid arterial axis. The dramatic size—six square blocks—is evident in Figure 131. Barton Myers Associates called for a network of gardens, lanes, and courts to pattern a new downtown.

The proposal by ELS/Elbasani and Logan with Robert Frankeberger called for the municipal government center to be a "knuckle" linking and

132.

The proposal of Barton Myers Associates, a network of gardens, lanes, and courts

(lower figure) realized with arcades and loggias (upper figure), was intended to set a

pattern for the rest of downtown. The pattern shown is from Phase 1 of the competition.

Octagonal shapes in both drawings define the main piazza.

133.

The "knuckle" proposed by ELS / Elbasani and Logan and Robert Frankeberger,

architects, is a concept that draws together sixteen particular planning and

design features.

134.

The Rainbow Guardian concept of Charles W. Moore and HNTB came from

Arizona's Indian heritage. According to Moore, "We were happy to find that

a big curved building could tie together the Old City Hall, the Palace Theater,

and the Dorris Opera House; could open up vistas to the State Capitol and Union

Station; and could even accommodate the big existing Municipal Building and its

'kiva' City Council Chambers. . . . All we had to do was get the colors right so

that the spirits would be pleased."

providing edges for the adjacent downtown district and a projected civic area to the south. Charles W. Moore and HNTB (Howard Needles Tammen & Bergendoff) used a rainbowlike arc of new buildings to define a large public space. This figure seemed appropiate because the Rainbow Guardian, associated with the myth of creation, is sacred to Native Americans in the region. A rainbow rendered in color and texture would be used to organize the new complex and serve as its conceptual focus. In each case the concept—crossed axes, city garden, network, knuckle, and Rainbow Guardian—guides and limits subsequent design development. To work catalytically such controlling concepts must have significance beyond the realm of the initial development. For example, the crossed axes become more important than other streets in the downtown grid; a knuckle indicates two focal developments, which it then links. A network of passages could spread elsewhere downtown.

Typological Control

Competitors in Phoenix chose two kinds of typological controls that by intention or inference could direct subsequent design. Some of the architects proposed that particular building elements were environmentally and historically appropriate and that these should become a basis for urban architecture in Phoenix. The element most frequently cited was the arcade, or colonnade, or loggia; competitors agreed that the utility of such an element in the southwestern climate, along with the historical precedents for it and its visual appeal, recommended it as a feature, even if not necessarily as an instrumental urban design concept. For the larger urban pattern, some architects proposed a web of passages connecting courtyards and patios.

Exemplars

Exemplars are specific models, in contrast to types, which are more general. For example, two competitors at Phoenix cited Diocletian's palace and the Escorial as suitable models for a new urban pattern in Phoenix. Seldom is it appropriate, however, to model new urban buildings after specific precedents. Too many factors differ between locales or historic eras. More often exemplars and types are blended to create generic models for controlling urban patterns and building forms. These controlling models, which mix specificity and generality, often have become the basis of design guidelines (discussed below).

135.

Barton Myers's Phase 1 scheme shows extensive use of arcades.

136.

Diocletian's palace, with its intensive grid of arcades and patios,

was one of the exemplars identified to guide development

in downtown Phoenix. From George Niemann, Der Palast

Diokletians in Spalato (Vienna: Alfred Hölder, 1910).

Norms

Normative standards for design control typically establish the maximum height or bulk of buildings, the percentage of openings in walls, the dimensions of setbacks, floor-area ratios, and so forth. These stipulations are the traditional stuff of zoning. In recent years they have been made more specific and more subtle in response to specific urban design objectives. The Downtown Plan for San Francisco offers an example. It specifies several protections of environmental quality. It guarantees that public sidewalks will have access to sunlight and that shadows will be reduced on certain public or publicly accessible open spaces. The table describing height limits shows how such norms may be written. The San Francisco Plan also establishes trade-offs between development and the creation of open space.[16]

Design Guidelines

Increasingly design controls are implemented through design guidelines, rules for design in a particular setting. They are not universal, and often there is a looseness about design guidelines that ensures variety and leaves room for special local character and circumstances. Design guidelines set out a body of intentions, concepts, and standards to be used in creating both buildings and open spaces. They are formulated by urban designers and planners as tools to be used by public bodies to establish goals, direct design, and help evaluate designs that are submitted for approval. They supplement the zoning maps and other quantitative standards that present the more general directions for an area plan. Guidelines are probably the most detailed design policy instruments that a community can create short of specifying designs. While they can give quantifiable standards, more often they are qualitative and require judgment in their application.

For the Phoenix Municipal Government Center, ELS/Elbasani and Logan with Robert Frankeberger proposed design guidelines as the appropriate way to direct and control development. The suggested controls took the form of limits to the height and mass of new construction and the height of cornice lines. Less specific guidelines that nonetheless exerted control called for new buildings to reflect features of adjacent or nearby buildings to assure coherence among elements of the district.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

More than they limit, the proposed design guidelines for Phoenix direct future design to achieve three urban design goals: definition of urban spaces (the street, plazas, and courtyards); enhancement of pedestrian experience (arcades and colonnades, appropriate adjacent uses, landscaping, water features, and public art); and response to climate (shading for open spaces, windows, and pedestrian circulation; orienting buildings with regard to sun and air movement; choosing fenestration with regard to daylighting and solar gain; and the use of appropriate materials).

A set of design guidelines like these includes a range of controls. Compatibility with adjacent buildings is a controlling concept . Calling for building forms that have extensive perimeters and fully occupy their sites to create interior courtyards and pedestrian spaces is a typological control . The urban patterns of Marrakesh, Seville, Cordova, Granada, Palermo, Kashan, and Isfahan are cited as exemplars . Certain standards are established, too, like a seven-storey height limit in the district.

Design guidelines will vary with the goals they seek to implement. In Phoenix the objectives are to create a place responsive to climate that will act as a model for subsequent design in the the region. In other cases the goal might be to attract middle-class residents back to the center city or to give new identity to a downtown retail complex. Elsewhere design guidelines suggest how to reclaim parts of the city from disuse (warehouse districts, waterfronts) and put them to new uses. In all of these cases design guidelines direct and moderate the catalytic process.

Design control ("design guidance") in England during the past decade or so has had a troubled history. Apart from expected complaints that controls restrict designers' freedom and that prescribed designs interfere with normal free-market response to the preferences of consumers or users, there is the serious question whether buildings constructed according to design guidelines are good or worth the trouble. There are important differences between the guidelines for an English county, however, and those appropriate for an American city center. For one thing, British guidelines suggest a specific visual character to assure that new buildings look at home in historical contexts.

The controls suited to catalytic urban architecture in America will be much less style oriented and instead will specify generic urban forms and the volumes building mass might occupy. Then, too, they will not attempt to guide design in a whole range of cities but only in a particular one. Typological controls do not limit design freedom any more than economic constraints and site orientation do. And we are confident that designs that respond to urban types and classic elements will be fundamentally correct even if their specific embodiments vary in quality.

Controls can do more than set limits; they can lead. Incentive zoning has a mixed history in the United States. Developers took advantage of the opportunities to increase the height of buildings in return for the creation of often unusable plazas. The transfer of development rights from historically valuable structures to the sites of new construction has a better record. Tying development in one locale to the creation of hous-

137.

Design guidelines suggested for the Phoenix Municipal Government Center, and possibly beyond.

Architects and sponsors working in the years to come deserve direction in employing features of a

master plan. Design guidelines like these translate general concepts into specific standards. These are

sampler; they do not exhaust the possibilities. ELS / Elbasani and Logan architects, 1985.

ing in another and to the support of public transit is a promising technique that assures some catalytic impact.

The very writing of guidelines can have extensive consequences. Because the floor area in San Francisco's Downtown Plan is measured not at the exterior wall plane but at the average line of the window glass, deep reveals and exterior ornamentation and modulation are encouraged in designs. More typically the definition of the floor area has been

determined by the building wall itself, thus encouraging the use of flat, plain building forms and surfaces, with window walls extended as far as possible.

Implicit Guidance

A final control, often neglected, is indirect: ideas applied in the development of one building may be applied to the development of another. For example, the attitude of the architects and developers of Ghirardelli Square toward the existing buildings suggested how other old buildings in the area might be treated. At the time there was no widespread agreement that an old factory might be both historically important and an urban amenity. But the way Ghirardelli was reclaimed set a precedent that others could follow.

In other cases a design feature rather than an attitude or point of view might suggest the treatment of subsequent developments. A strong commitment to second-level pedestrian movement in San Francisco's Golden Gateway development was mirrored in a similar system in the adjacent Embarcadero Center. The extension of Milwaukee's skywalk system across the Milwaukee River creates a foothold (a beachhead, actually) for extending it beyond the Grand Avenue. The color, detailing, orientation, massing, and so forth of one development can respond to those of an earlier complex.

We refer to these implicit design suggestions as knobs, hooks, links, and footholds. Through them developments create linkages and continuity across streets and property lines. Although there is value in an urban collage of dissimilar developments, there is also value in linkages and continuity, something that the American landowning system discourages. But as the arcades of European cities demonstrate, it is possible for connections to create continuity even where uses and ownership change. Knobs, hooks, links, and footholds are subtle ways in which architecture can be catalytic. They are suggestive rather than legislated. The architects and urban designers planning them must talk with each other about the larger urban pattern and experience. These implicit architectural influences are the most time-honored way of establishing urban cohesiveness. They are basic to the very concept of urban catalysis; their power and potential should never be underestimated.

Design controls and zoning are extensive subjects that need lengthier description and analysis. Our purpose here is simply to make the case for a sophisticated control system to direct and moderate urban catalysis. As catalysis in chemistry requires control and suggests a managed reaction, so too does urban catalysis. The unbridled marketplace can produce and has produced both good and bad—but usually accidental—catalysis in cities. We plead for controlled change in service to a collective idea of urban design quality. Design and development controls are increasingly necessary as part of the public-private partnership that seems the soundest basis for a contemporary American urbanism.