Water/Magma (Hydrovolcanic) Interaction: Field and Laboratory Aspects

Recognition and study of hydrovolcanic features in a volcanic field is an important step in locating and characterizing a potential geothermal resource. These features indicate not only a potential magmatic heat source but also the possible existence of groundwater. Water is generally the dominant volatile constituent in volcanic systems. It is also the chief geothermal "working fluid" because its volume changes, which occur with varying temperature and pressure, produce thermodynamic work. In this context, water is required to transfer thermal energy from the earth to the point of exploitation, whether for direct use or production of electricity. Thus, abundant groundwater is necessary for development of a geothermal resource except in cases of hot dry rock resources, where water is artificially supplied to the thermal reservoir.

Carbon dioxide is another common volatile substance in volcanic systems. Like water, it may interact with magma, but because of its phase relationships, it cannot be considered a condensible gas in most geological environments, and thus its heat-transfer qualities must be addressed separately. The presence of carbon dioxide can greatly alter water/magma interaction and the heat convection to the earth's surface.

In Chapter 1, we introduced hydromagmatism and hydrovolcanism as general terms to describe the physical and chemical

Fig. 2.8

Temperature-depth diagram depicting several thermal gradients and their corresponding influence

on geothermal gradients at the earth's surface. This diagram shows the range of typically observed

steam fields (hatched) and the near-surface perturbations of geothermal gradients that are caused

by groundwater and aquifers.

(Adapted from Rowley, 1982.)

processes that develop where magma and magmatic heat interact with ground or surface water in magmatic and volcanic environments, respectively. There are many geologic terms that refer to specific aspects of these processes, such as hydrothermal, phreatic, phreatomagmatic , and hydroclastic (see Glossary, Appendix G). In addition, the text of Fisher and Schmincke (1984) explains in detail various terms that relate to the interaction between water and magma, magmatic heat, and lava. In the following discussions, we will review the aspects of hydrovolcanism that greatly affect development of a geothermal reservoir. Hydrovolcanism, recognized for over a century, has recently been more widely acknowledged in field relationships and as a theoretical basis for interpretation of volcanic activity.

Basic Concept

Initial ideas about the role of ground and surface water in volcanism developed during the last century. These perceptions were formed particularly through observations of unusually explosive periods of Hawaiian volcanism, during which ground-water entered rifts along which normal lava fountaining had occurred (Jaggar, 1949), as well as through examination of fragmental basalts found where lava had entered water (Fuller, 1931). Three well-documented eruptions during the late 1950s and early 1960s brought an increased awareness of hydrovolcanism: Capelihnos, Azores (Tazieff, 1958; Servicos Geologicos de Portugal, 1959), Surtsey, Iceland (Thorarinsson, 1964), and Taal, Philippines (Moore et al ., 1966). Fisher and Waters (1970), Waters and Fisher (1971), and Heiken (1971) expanded the concept of phreatomagmatic eruptions characterized by steam-rich eruption columns, base surges, and typical landforms such as maars, tuff rings, and tuff cones. As a result of this work, numerous 20th century phreatomagmatic eruptions are now recognized—most of them have formed maar-like craters (for example, Self et al ., 1980). We also now realize that after cinder cones, phreatomagmatic vents (tuff rings, tuff cones, and maars) are the most abundant terrestrial volcanic landform.

An interesting paradox has emerged in studies of hydrovolcanism: interaction between magma (lava) and water can be passive, explosive, or even both in situations where all other conditions are apparently the same. This anomaly is illustrated along the southern coast of Hawaii, where in some cases lava flowing into the ocean quenched passively to form pillow lavas and in other cases it was explosively fragmented during quenching to form tephra cones along the beach (Fisher, 1968). Explanations of this paradox have benefited enormously from information derived from analog phenomena such as industrial accidents in which a molten substance such as iron has caused an explosion when it was rapidly introduced to water. This type of situation is a potential safety problem, for example at nuclear reactors (Witte and Cox, 1978). The term commonly used for the industrial analog, fuel-coolant interaction (FCI), can be applied to volcanic processes involving the interaction of two materials, one at a temperature above the boiling point of the other—where the interaction varies from passive quenching and film-boiling circumstances to explosive situations in which the two materials mix and exchange heat at catastrophic rates.

Heiken (1971) studied a number of phreatomagmatic volcanoes in southeastern Oregon and correlated the volcano morphology with abundance and depth of groundwater. As summarized in Table 2.3, characteristic volcanic landforms range from low-profiled tephra rings surrounding a wide crater to steep-sided tephra cones with relatively smaller craters. The former type are termed tuff rings (or maars if the crater extends below the level of the prevolcanic ground surface); the latter type are called tuff cones (Fig. 2.9). Sheridan and Wohletz (1981; 1983a) extended this characterization

of hydrovolcanic landforms by recognizing that they form parts of polygenetic volcanoes, such as composite cones and calderas in which characteristic tephra accumulations of tuff cones and rings may be found (see Chapter 1).

Of the various types of tephra deposits produced by hydrovolcanism, pyroclastic surge (base surge) deposits are most distinctive (Fisher and Waters, 1970; Wohletz and Sheridan 1979). The four hydroclastic-tephra bedforms illustrated in Fig. 2.10 include (a) breccias formed at the vent by explosions or in distal regions by laharic remobilization, (b) sandwaves that show a variety of dune-like bedding structures ~1 cm thick (Crowe and Fisher, 1973; Schmincke et al ., 1973), (c) massive beds that may resemble small pyroclastic flows, and (d) planar beds. In general, these tephra bedforms are deposited by pyroclastic surges, but fallout and pyroclastic flows also contribute to deposition of hydroclastic tephra. Identification of the depositional mechanisms requires careful examination of features such as those listed in Table 2.4.

Because of the variety of possible textural features found in any hydrovolcanic deposit, it is helpful to characterize the tephra facies described in Table 2.5. Some facies relationships depend on the type of vent structure; for example, facies relationships for pyroclastic surge deposits surrounding monogenetic tuff rings (Wohletz and Sheridan, 1979) include near-vent sandwave facies, massive facies at intermediate distances from the vent, and planar facies at distal portions of the deposit. In contrast, Frazzetta

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

et al . (1983) showed that Vulcano, a composite cone with relatively steep slopes, has near-vent planar facies, massive facies on cone slopes, and sandwave facies at distal portions of the deposit at and beyond the base of the cone. In most cases, the positive designation of a tephra facies in hydrovolcanic deposits will require a detailed analysis of bedform textures (Fig. 2.11). Recognition of these facies relationships can help locate a buried or exhumed vent structure, as related by Crisci et al . (1981).

Wet and Dry Facies Relationships

From field observations, we have realized a significant concept about the textural relationships of various hydrovolcanic tephra deposits. Wohletz and Sheridan (1983) discuss in detail the existence of two fundamentally different types of hydrovolcanic tephra deposits: dry and wet. This designation reflects the physical state of the tephra when it is emplaced: dry deposits show little textural evidence of the presence of moisture, and wet deposits show sedimentary, textural, and diagenetic evidence of wet emplacement. Table 2.6 summarizes the field observations that help characterize these two types of deposits.

The significance of wet and dry characterization for hydrovolcanic tephra deposits will become clear during the following discussions of field relationships, theoretical eruption and emplacement models, and the development of hydrothermal systems in country rocks surrounding vent areas.

Fig. 2.9

Hydrovolcanic landform vs geohydrological environment. In unsaturated environments, basaltic

volcanism commonly produces cinder (scoria) cones by eruptions of relatively low energy.

In areas of abundant water, eruptions vaporize the fluid, which results in explosive activity and

the formation of tuff rings and cones. In deep water, extrusions of basalt are passively

quenched and form pillow lavas.

(Adapted from Wohletz and Sheridan, 1983a.)

Hydrovolcanic eruptions disperse tephra in clouds of steam. Where water is abundant, the expansion of steam occurs in the steam dome (a two-phase region), and an appreciable amount of condensed water is emplaced with the tephra. Where water is less abundant, the steam expands in its superheated region and is more readily separated from tephra during emplacement so the deposits remain relatively dry. Observations of the eruptions of Surtsey volcano illustrate this expansion process (Thorarinsson et al ., 1964). Tephra and high-pressure water vapor were erupted in plumes called "cock's tails" or "cypressoid" jets. The water vapor was not visible until it reached lower pressure after the jets had traveled several hundred meters from the vent. At that point, saturated steam was visible in the jets of tephra, indicating that it condensed in the steam dome. This steam was carried along with the tephra jets until their emplacement on the slopes of the emerging volcano. Some of the water vapor separated earlier from the jets as optically transparent, superheated steam. It later

Fig. 2.10

Four major textural types of hydroclastic deposits

produced by explosive hydrovolcanic eruptions.

Explosion breccias are typical of near-vent

tephra deposits, whereas sandwave (dunes),

massive, and planar bedded tephra deposits are

common to pyroclastic surges and flows (Wohletz

and Sheridan, 1979). Another textural type,

the laharic breccia, forms by liquefaction of these

deposits if there is an abundance of condensed

steam or rainfall.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

became visible as it cooled and condensed in the atmosphere, rising as billowing steam clouds above the jets.

Other observations mentioned by Wohletz and Sheridan (1983) support the hypothesis that the physical state of water/steam during eruption is determined by the mass ratio of water to magma interacting in the vent. This hypothesis has evolved as detailed studies of many hydrovolcanic vents around the world have documented the dependence of eruptive energy, tephra dispersal, and the resulting vent landform on the water:magma mass ratio (summarized earlier in Chapter 1). Figure 2.12 illustrates typical hydrovolcanic bedforms and their deduced water:magma mass ratios.

Through the interpretation of deposits, one can show that many volcanoes demonstrate cyclic eruptive behavior (Chapter 1), in which the water:magma mass ratio varies with time. Sheridan and Wohletz (1983a) noted two trends at many volcanoes. A dry trend, typically found in tuff rings, is indicated by deposits that show a decreasing abundance of interacting water with time so that final eruptions can be entirely magmatic. A wet trend is illustrated by tuff cones in which the initial eruption is magmatic and the final bursts are so wet that tephra form lahars as they are emplaced. Using the information gained from these observations, it is possible to place constraints on both the water:magma ratio during the course of an eruption and the availability of water for potential hydrothermal systems associated with the volcano.

Fig. 2.11

Pyroclastic surge facies as designated by bedform statistics. Section S-7 represents the sandwave

facies with abundant dune bedforms; U-4 is a massive facies example showing planar, massive, and

dune bedforms; S-1 is an example of planar facies with mostly planar and massive bedforms.

Section U-8 is ambiguous; after detailed analysis of bedform transitions by Markov analysis

(Wohletz and Sheridan, 1979), it is classified as sandwave facies. Bedform types are shown as

P (planar), M (massive), or S (sandwave), as defined in Fig. 2.10. Occurrences of these types are

further numbered from the base of the deposit.

(Adapted from Wohletz and Sheridan, 1979.)

Polygenetic Volcanoes and Calderas

The phenomenon of hydrovolcanism is not associated solely with eruptions at small, monogenetic volcanoes. The following descriptions illustrate the significance of hydrovolcanic processes in (a) wide-spread tephra deposits from silicic calderas, (b) the development of wet and dry cycles at composite cones, (c) the evolution of calderas, and (d) pyroclastic episodes during the eruption of domes of intermediate to silicic composition (see Chapter 5).

Taupo

The Taupo volcanic zone of New Zealand's North Island is one of the best studied examples of silicic volcanism. An important hydrovolcanic feature of this volcanic field is the extremely widespread, fine-grained silicic tephra deposits, especially those from the Taupo volcanic center (Healy, 1962; 1964).

| ||||||||||||||||||

Self (1983) presented an extensively documented account of the Wairakei eruption (20,000 ka), which produced the Oruanui Pumice Formation (Vucetich and Pullar, 1964) and the Wairakei Breccia, both of which are part of the Wairakei Formation. Self addressed the exceptionally fine grain size, wide dispersal, high content of accretionary lapilli (up to 33 wt%), and irregular thickness distribution—features that Self and Sparks (1978) noted as indicators of silicic, phreatomagmatic (Phreatoplinian ) volcanism. Figure 2.13 illustrates the stratigraphy of the Wairakei Formation, which consists of interbedded, fine-grained pyroclastic fall and flow deposits as well as two main phreatoplinian phases that were followed by ignimbritic phases. Member 1 has a median diameter of 4.0 f (0.064 mm) even near the source and is representative of the typical phreatomagmatic materials shown in Fig. 2.14.

Heiken and Wohletz (1985) described volcanic ash samples and their phreatomagmatic textures from this section. Through interpretation of tephra deposits, Self (1983) illustrated the eruption sequence and phreatomagmatic factors of the Taupo eruption (Fig. 2.15). More detailed descriptions of geothermal studies in the Taupo region are given in Chapter 4.

Vulcano

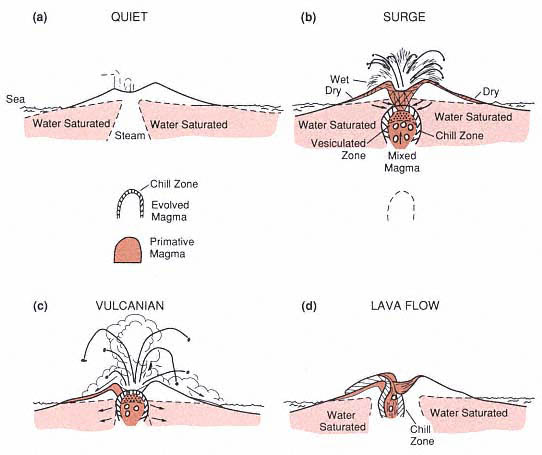

The Island of Vulcano in the Aeolian archipelago of Italy is a classic example of hydrovolcanic activity. The Fossa cone of Vulcano has been historically active and poses an ongoing hazard (Keller, 1980). Mercalli and Silvestri (1891) observed the most recent eruptive episode and described the eruption phenomena now termed Vulcanian . Frazzetta et al . (1983) built on the work of Sheridan et al . (1981) to interpret the detailed stratigraphy of the cone and show how hydrovolcanism contributed to the five most recent episodes of volcanism; their summary of the Fossa tephra stratigraphy is illustrated in Fig. 2.16. These authors further proposed that all five episodes of volcanism were characterized by a cyclic eruption pattern that consists of the four stages shown in Fig. 2.17.

(1) Initial quiet, fumarolic activity was stimulated by heat transfer from (possibly) two magmas of differing compositions that rose below the volcano.

(2) A triggering event initiated a mixing of the two magmas, which was followed by further rise of the mixed magma to the surface where it contacted ground-water. The resulting hydrovolcanic eruptions of pyroclastic surges

comprised chilled, nonvesiculated tephra that progressed from wet to dry.

(3) As the groundwater source was separated from the magma by a steam envelope, the eruptions became magmatic, expelling vesiculated tephra interspersed with the chilled tephra.

(4) The cycle's final stage is marked by eruption from the pumiceous cap of the magma and, later, extrusion of an obsidian-cored lava flow. Frazzetta et al . (1983) interpreted the products of the most recent eruptive cycle with respect to water:magma ratios, as shown in Fig. 1.22.

Fig. 2.12

An idealized hydrovolcanic deposit section

illustrating typical bedding textures and

bedforms and their inferred water:magma mass

ratios (Rm ). Initial eruptions, represented by

the basal pumice fall, involved little or no

external water; however, in later eruptions,

the stratigraphic section records bedforms

that indicate increasing water:magma ratios.

For ratios >1.0, caused by eruptions into a

standing body of water, pillow lavas/breccias

and peperites are usual, as are lahars, which

commonly occur in eruptions of high

water:magma ratios on land.

Vesuvius

The ejecta deposits of another long-active and much-studied volcano, Vesuvius, indicate that hydrovolcanic activity is significant during its eruptive cycles (Barberi et al., 1981; Rosi and Santacroce, 1983). The AD 79 eruptions of Vesuvius are among its best documented in terms of actual observations (Pliny the Younger, 1763; Radice, 1972), deposit descriptions (Sigurdsson et al ., 1985), and interpretations of eruption mechanisms (Sheridan et al ., 1981). Figure 2.18 shows representative tephra stratigraphic sections from archaeological excavations at three Roman sites that were devastated by

Fig. 2.13

Wairakei Formation tephra stratigraphy for

locations within 20 km of the vent in Lake

Taupo, New Zealand. Members 4 and 6 (m4,m6)

were previously named the Oruanui Pumice

Breccia and Wairakei Breccia, respectively.

(Adapted from Self, 1983.)

Fig. 2.14

Grain-size characteristics of the Wairakei Formation (Self, 1983). (a)Median diameter (Mdf ) ) vs sorting

coefficient (sf ) is shown for the various members (m1,m2,..) illustrated in Fig. 2.13; also noted are

textural types, including accretionary lapilli (crushed), lithic/pumice-rich ignimbrite, and base surge.

The dashed field represents pyroclastic flows. (Adapted from Wright et al ., 1981.) (b) Grain-size

fractions for m4 and m6: the dashed field represents pyroclastic flows; coarse variant shown by

symbols. (Adapted from Walker et al., 1980.) (c) Grain diameter frequency curves for fallout products

of m2 and m6 show gradual loss of coarse products with increasing distances from the source

(curve numbers in kilometers). (d) Cumulative probability distribution of size fractions (f ) for Plinian

and phreatoplinian deposits is compared to the distribution of a representative m3 sample.

(Adapted from Carey and Sigurdsson, 1982, and Walker, 1981.)

the eruptions. Fallout deposits of white and gray pumice from early magmatic eruptions were followed by hydromagmatic products emplaced as surges, pyroclastic flows, and lahars—all containing abundant lithic ejecta derived from carbonate aquifer rocks that underline the Somma Vesuvius at a >2-km depth. Figure 2.19, the model presented by Sheridan et al . (1981), interprets the stratigraphy and illustrates the effects of hydrovolcanic activity during the devastating phases of the eruption. Accretionary lapilli, abundant in the upper portions of the tephra stratigraphy, were studied in detail by

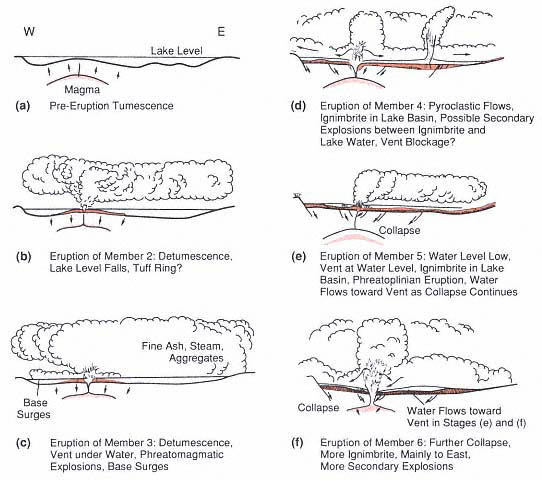

Fig. 2.15

Wairakei eruption model showing the sequential stages or eruption of the various

members and periods of lake water/magma interaction.

(Adapted from Self, 1983.)

Sheridan and Wohletz (1983b), who described possible mechanisms for their formation in wet eruption plumes.

Contrasting hydrovolcanic behavior is evident in the early-stage interaction with water at Vulcano and the late-stage interaction shown at Vesuvius. One general explanation for this contrast is the overall hydrologic setting of these volcanoes: Vulcano is an island edifice characterized by abundant near-surface groundwater, whereas Vesuvius is built on a sedimentary platform with a deep aquifer system. Access of water to the vent system at Vulcano gradually decreases during eruptive episodes as magma congeals along vent walls where water initially infiltrates. At Vesuvius, access of groundwater to the magma chamber and vent conduit is initially limited by thermal metamorphic rocks that have sealed fractures. However, as the conduit and chamber wall rocks are fractured by expansion of magmatic gases early in Plinian eruptive episodes, groundwater gains access to the magma, especially after overpressures in the magma body and conduit have fallen below the local thermally perturbed hydrostatic

Fig. 2.16

Composite stratigraphic section illustrates

the hydrovolcanic cycles of the Fossa volcano

at Vulcano, Italy. The Pietre Nere, Palizzi,

Commenda, and Pietre Cotte cycles all show

a progression from hydrovolcanic eruptions to

emplacement of lava flows.

(Adapted from Frazzetta et al ., 1983.)

pressure. The behaviors exhibited at Vulcano and Vesuvius are generally termed shallow and deep hydrovolcanic eruptions, respectively; the former becomes dryer and the latter becomes wetter as eruptions progress.

Throughout the entire Latium volcanic province of Italy, hydrovolcanism has been a vital component in the development of caldera complexes such as those of Vulsini, Vico, Sabatini, Albani, and the Phlegraen Fields. Broad, low-profile calderas with widespread, fine-grained silicic tephra characterize these volcanic areas. Because of their geothermal importance, we will describe them in detail in Chapter 4.

Petrography of Hydrovolcanic Tephra Constituents

Hydrovolcanic tephra may show aspects of both magmatic and hydrovolcanic origin; in such cases, petrographic inspection is necessary to determine the relative proportions of the two endmember processes. Fisher and Schmincke (1984) used the terms pyroclastic and hydroclastic to distinguish products of magmatic and hydrovolcanic explosions, respectively. Table 2.7 reviews the salient features of hydroclastic products.

Hydroclastic tephra are generally distinguished from pyroclastic tephra by their fine grain size. However, this distinction is not always apparent, especially in hydroclastic tephra sampled at near-vent locations where fine fractions have not been deposited. Figure 2.20 shows plots of sorting vs median diameter for four characteristic tephra bedforms produced by hydrovolcanic activity. Although these statistics are often

Fig. 2.17

This schematic model of typical Vulcanian eruption cycles at Vulcano is based upon interpretation of

stratigraphic successions shown in Fig. 2.14. Activity progresses from (a) quiet fumarolic emissions to

(b) magma vesiculation and surge eruptions caused by primitive magma intruding into older evolved

magma and interaction with groundwater. (c) The development of a steam chimney above the magma

reduces direct contact between water and the melt; steam explosions eject comminuted older lavas and

some pumice, producing surge and fallout deposits. (d) The final stage is marked by eruption of a

pumice fall and emplacement of a lava flow from the chilled zone of the magma body.

(Adapted from Frazzetta et al ., 1983.)

sufficient to characterize hydroclastic tephra, we advocate further analysis of size distributions by the techniques described by Sheridan et al . (1987) to separate subpopulations from the overall sample distribution. This method involves the detailed analysis of wet and dry sieve data and sample separation procedures described in Appendix A.

Constituents of hydroclastic tephra, including glass, crystals, and lithic fragments in various proportions, are sensitive to the emplacement mechanism and magma composition. Figure 2.21 illustrates the variety of tephra constituents that characterize tuff rings and tuff cones. One of the most distinguishing features of these tephra is the amount of glass alteration in samples of wet and dry hydrovolcanic facies. Basaltic glass readily alters to palagonite, a complex combination of zeolites and smectites; rhyolitic glass alters to hydrated glass, which can crystallize to fine-grained quartz, potash feldspar, and clays. Although such alteration generally occurs in any tephra deposit through weathering and diagenetic processes, stratigraphic

Fig. 2.18

Representative stratigraphy of AD 79 pyroclastic deposits exposed in archaeological excavations

along the coastal side of Vesuvius; FA = pumice fallout, FL = pyroclastic flows, and S = surges.

The basal white and gray pumice fallout was from early magmatic eruptions, and the upper

pyroclastic flows and surges are products of later hydrovolcanic eruptions.

(Adapted from Sheridan et al ., 1981.)

Fig. 2.19

Model of AD 79 Plinian eruptions at Vesuvius. This model, temporally and phenomenologically

constrained by accounts of Pliny the Younger (Radice, 1972), shows (a) the initial Plinian column

eruption, (b) the decline to intermittent magmatic and hydromagmatic explosions, and (c) the

terminal hydromagmatic phase that produced wet pyroclastic flows and surges. The beginning

of hydromagmatism, during the intermediate stage, is associated with the failure of magma

chamber walls, which added a thermally metamorphosed lithic constituent to the tephra and

allowed aquifer waters to flow into the chamber.

(Adapted from Sheridan et al ., 1981.)

information supports the conclusion that the alteration can also result when abundant hot water vapor is emplaced with the deposit.

Weathering and diagenetic effects, including the posteruptive saturation of tephra deposits by rain or groundwater, make it difficult to evaluate the timing of palagonitization and hydration; however, pertinent stratigraphic information can be useful (Fig. 2.22). Where fresh and altered tephra appear in alternating layers above the groundwater table, a strong argument can be made that alteration took place at the time of tephra emplacement. Proximity of altered tephra to a vent or fault is indicative of postemplacement alteration by hydrothermal fluids. Diagenesis below the groundwater table can be assessed for a region by determining the lateral extent of altered tephra and the presence of alteration zones that cross bedding planes.

Wet deposits can be distinguished from dry ones by the degree of glass alteration. Figure 2.23 shows that palagonitization of basaltic tephra is a function of median grain size, but for diameters <0.1 mm, palagonitization is most prevalent in samples from wet facies bedforms. This observation is not surprising if one considers the results of experiments with palagonite formation that demonstrate a strong dependence on temperature (Fig. 2.24a). Palagonitization also has a significant effect on glass chemistry; bulk chemical analysis of partly palagonitized tephra may show that its composition is considerably different than that of its parent (Fig. 2.24b).

Analyses of clast morphology by optical and electron microscope also provide important data for classifying tephra as pyroclastic or hydroclastic (Heiken, 1971; Heiken and Wohletz, 1985). Table 2.8 summarizes clast morphologies that are useful in understanding the eruptive mechanism (grain shape), transport or emplacement process (edge modification), and water abundance (clast alteration/palagonitization). Wohletz (1987) described these features for several examples of hydrovolcanic associations.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fig. 2.20

Grain sizes of hydrovolcanic tephra deposits of different bedding textures are shown by plots of

sorting coefficient (sf ) vs median diameter (Mdf ). Whereas pyroclastic surge bedforms (sandwave,

planar, and massive) range in median diameter from 2.0 to 0.063 mm, fine-ash beds demonstrate

the intense tephra fragmentation capability of hydrovolcanism with median

diameters of 0.063 to 0.022 mm.

(Adapted from Sheridan and Wohletz, 1983a.)

Fig. 2.21

This triangular diagram of hydrovolcanic tephra

constituents shows the relative contribution of

fresh glass, altered glass, and crystal and lithic

material. Fields for tuff rings and cones reflect

the relative proportions of these constituents in

different bedforms. The greater relative

abundance of altered glass for tuff cones

attests to the greater abundance of water in

the erupting system.

Fig. 2.22

Example of stratigraphic and structural settings for altered (palagonitized and hydrated) tephra

deposits. (a) Altered tephra (cross-hatched) may exist around a vent area as a result of hydrothermal

circulation. Such alteration is relatively insensitive to tephra bedding planes, but it does not show

lateral continuity away from the vent. (b) Palagonitization and zeolitization below a groundwater

table show lateral continuity and may cross bedding planes between tephra of different

depositional character. (c) Alteration may be structurally controlled along faults through which

hydrothermal fluids have migrated. (d) However, when tephra alteration occurs rapidly during

eruption and emplacement and before cooling, the altered tephra may be intercalated with

relatively fresh tephra layers. This alteration is relatively insensitive to

the groundwater table and initial dips of the strata.