Conclusion

This chapter began by investigating visiting rituals as a form of "social work." This formulation acknowledges both the need to actively maintain neighborly friendships and the labor—mental, physical, and emotional—that sustains them. The framework of the public, the private, and the social spheres allows us to reorient our perspective and see social activities as "work," the active weaving together of the fabric of society. Building on the writing of di Leonardo and others, we can expand our understanding of the "social work" of women beyond kin networks to look at the neighborhood, the village, and the town. Women and men within the social sphere dynamically mediated the various forces of society—tying the family to the community, neighbor to neighbor, the individual to the collectivity.

Furthermore, the practice of visiting reveals that between 1820 and 1865, laboring women were not confined to domestic space, as the label "private" suggests. They traveled to see distant neighbors and friends; they attended lectures; they organized church events, bees, and the like. The diaries, letters, and autobiographies demonstrate that women's networks reached out broadly and embraced people not related by blood. As in the colonial period, visiting linked households in an elaborate system of economic and social exchange. Work intertwined with sociability; both were fundamental to survival. Visiting provided essential services and labor to households and bound neighbors and kin.

The extensive gender integration of activities in the social realm refutes the belief that working people observed a culture of separate spheres. Men's involvement in the capitalist market did not render them inept at domestic affairs. Women's expansive everyday activities launched them into orbits far beyond the confines of the private sphere. Unlike middle-class women, working women did not control channels of communication within the family through exclusive access to visiting and correspondence. Juxtaposed to the social dimension, the private sphere seems small indeed, a shadow of working women's universe.[65]

The central role of visiting in the lives of working people raises some interesting questions about the value of "social work" and the status visitors derived from it. By dissipating the loneliness of others, comforting the bereaved, caring for the infirm, attending the births of future

generations, engaging in the labor-intensive tasks of providing shelter and clothing, both men and women performed services that one century later would generate multibillion-dollar industries and keep federal and state governments scrambling. The industrializing organization of work over the course of the nineteenth century increasingly impinged upon working people's capacity for engaging in social exchange. However, diarists regularly moved in order to find employment, which profoundly disrupted local networks. They struggled to establish new ties and to maintain old ones through correspondence and visiting.

The question remains: did women and men derive a different kind of status in the social sphere than they did in the public or private, a status premised on their centrality to the communal enterprise and the provision of essential services? And if working women visited (slightly) more than working men in antebellum New England, but did so increasingly over the following hundred years, how did the value of their services change over time?

If visiting became increasingly feminized, as the literature suggests, did it, like other occupations, decline in its prestige and value? In this system of exchange, women, as "participant intermediaries," had the opportunity to exercise a certain kind of freedom and initiative as well as draw on important resources for the household. Through activity in the social sphere, were women able, as Osterud suggests, to redress gender hierarchy? While they did not direct all social activities, they indisputably acted at the heart of managing them. Their influence was not limited to individual households (private), nor was it public (affecting the state). It was social.

Figure 1.

Martha Osborne Barrett dresses in costume for a party of the

Unity Club, a theatrical group affiliated with the Unitarian Church

in Peabody, Massachusetts. Photograph, 1890. Courtesy of the

Peabody Historical Society, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Figure 2.

Four female weavers at their looms. Engraving from Summer Pratt, Worcester,

Massachusetts, Letterhead, 1860. Courtesy of the Museum of American Textile

History, North Andover, Massachusetts.

Figure 3.

Leonard Stockwell, a paper-mill worker and farm laborer.

Photograph. From Leonard Stockwell Memorial Volume ,

ca. 1880. Courtesy of the American Society, Worcester,

Massachusetts.

Figure 4.

The Unitarian Church in Peabody, Massachusetts, which Martha Osborne Barrett

attended for the second half of the nineteenth century. Photograph, 1906.

Courtesy of the Peabody Historical Society, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Figure 5.

Handwritten page from the diary of Sarah Trask, shoebinder, January 24–26, 1849.

Courtesy of Beverly Historical Society and Museum, Beverly, Massachusetts.

Figure 6.

Image of an elegant woman pasted in Sarah Trask's Diary, 1851. The artist titles

the engraving "A Lover's Signal." Sarah titles it "This is Sarah presented by C. H.

Lewis." Beneath the image she recorded a poem: "For never can my soul forget / The

loves of others years / Their memories fill my spirit yet / I've kept them green with

tears." Courtesy of Beverly Historical Society and Museum, Beverly, Massachusetts.

Figure 7.

Brigham Nims, box factory worker,

farmer, and teacher, poses for a silhouette,

a popular form of representing one's

likeness in antebellum New England.

Courtesy of New Hampshire Historical

Society, Concord.

Figure 8.

Laura Nims, sister of Brigham Nims,

is made to look slightly ridiculous with

the exaggerated features of her dress.

Silhouette. Courtesy of New Hampshire

Historial Society, Concord.

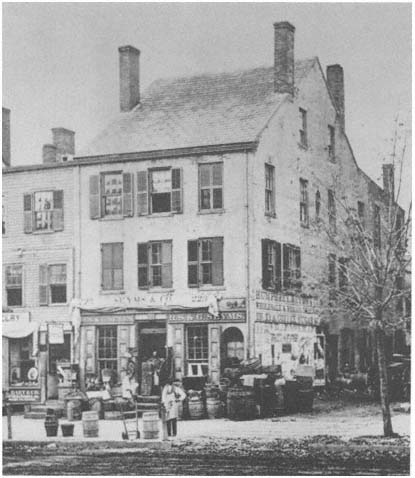

Figure 9.

Holdridge Primus, father of Rebecca Primus, standing on sidewalk in front of

Seyms & Co., Grocers, where he worked for forty-seven years. Main Street, Hartford,

Connecticut. Trade card, ca. 1860. Courtesy of Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford.

Figure 10.

Chloe Fales Adams Metcalf on her hundredth birthday. Chloe is seated at the center of her family and friends. Photograph, 1897. Courtesy of Museum of American Textile History, North Andover, Massachusetts.

Figure 11.

In the mid-1840s Hannah Thurston Adams and Mary Agnes Adams commissioned

a portait of themselves from an itinerant portrait painter. They stand proudly holding

the account book from their tailoring business. Oil on canvas, artist unknown,

ca. 1845. Photograph by Thomas Neill. Courtesy of Old Sturbridge Village,

Sturbridge, Massachusetts.

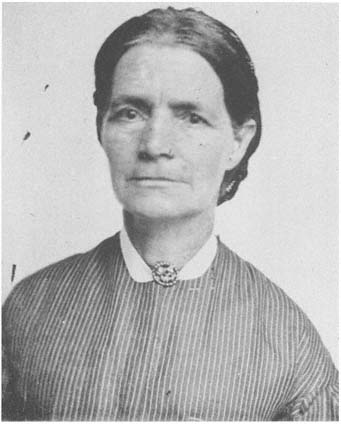

Figure 12.

Eliza Adams, sister of Hannah and Mary Adams, worked as a textile

operative and saved her money to buy a farm in western Massachusetts.

As a single woman, she adopted and raised two daughters while also

providing a home for other young orphans. Tintype, ca. late 1840s.

Private collection.

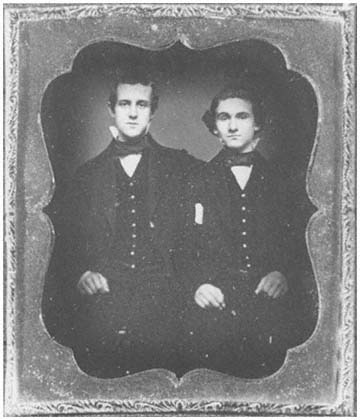

Figure 13.

Four anonymous working women link arms and directly confront the camera.

Ambrotype, ca. 1860. Private collection.

Figure 14.

Two anonymous friends affectionately pose for the camera.

Note that the man on the left has his arm around the man on the right.

Daguerreotype, ca. 1860s. Private collection.

Figure 15.

After both parents died in an accident, Mary Giddings Coult Jones

taught school for several years in New Hampshire. She married a farmer

and moved to his home in Connecticut in 1853. Photograph, ca. 1860s.

Courtesy of the Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford.

Figure 16.

A staff of domestic workers. Tintype, ca. 1860–1880. Private collection.

Figure 17.

Southwestern view of Gloucester, Massachusetts. Francis Beanett, Jr., grew up

in this prosperous fishing town, where he worked as a clerk and began keeping

his diary. Engraving, 1839. From Historical Collections , by John Warner Barber

(Worcester, Mass.: Dorr, Howland & Co., 1839). Courtesy of the Society for the

Preservation of New England Antiquities, Boston.

Figure 18.

This quilting party in western Virginia, like those in New England, includes both men

and women, along with animals and children of all ages. Engraving, 1854. From

Gleason's Pictorial Draw-Room Companion , vol. 7 (October 21, 1854), p. 249.

Courtesy of American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

Figure 19.

Charles A. Benson served as the steward on the bark Glide on its maiden voyage to

East Africa in 1861. On its next sojourn in 1862, he began keeping a diary to send

back to his wife, Jenny. Oil painting by William Stubbs. Photograph by Mark Sexton.

Courtesy of Peabody & Essex Museum/Peabody Museum Collection,

Salem, Massachusetts.

Figure 20.

The Reverend Peter Randolph, an ex-slave, regularly preached

to white audiences in the North. Photograph, 1893. From

Slave Cabin to Pulpit: The Autobiography of Rev. Peter

Randolph; The Southern Question Illustrated and Sketches

of Slave Life (Boston: James H. Earle, 1893).

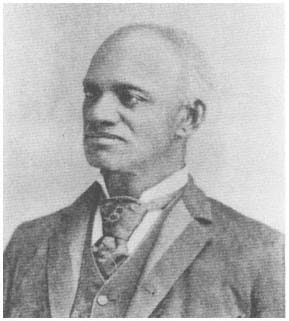

Figure 21.

The Reverend Samuel Harrison was a shoemaker as well

as a minister. He served as chaplain to the 54th Massachusetts,

the first black regiment to fight in the Civil War.

Daguerreotype, 1849. From His Life Story as Told by Himself

(Pittsfield, Mass.: Eagle Publishing, 1899).

Figure 22.

David Clapp worked as an apprentice printer while he kept his

diary in the early 1820s. He later became a successful printer in

Boston. Engraving, 1894. From Memoir of David Clapp , by

William B. Trask (Boston, 1894). Courtesy of American

Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

Figure 23.

Bethany Veney wrote her life story, recounting her life under

slavery and her move to settle in New England. Engraving, 1889.

From Narrative of Bethany Veney, a Slave Woman

(Worcester, Mass., 1889).

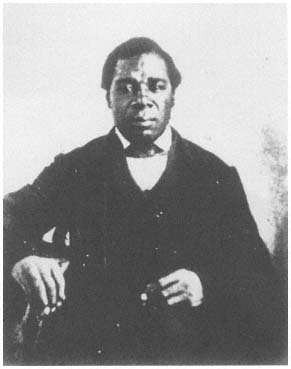

Figure 24.

Isaac Mason, an ex-slave, wrote his autobiography in the

late nineteenth century. Photograph, 1893. From Life of

Isaac Mason as a Slave (Worcester, Mass., 1893).

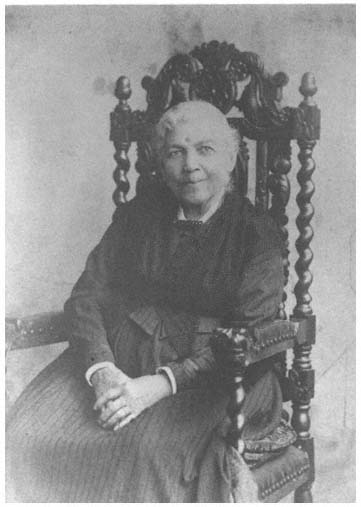

Figure 25.

Harriet A. Jacobs recorded her harrowing tale of life under slavery, her

heroic escape, and her struggle to make a living in the North. Photograph,

1894. From her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,

Written by Herself , edited by Jean Fagan Yellin (Cambridge, Mass.:

Harvard University Press, 1987).