XI—

The Studio

Yet Guston could not lend himself to the kind of posturing that de Chirico's views too often represent. As James Thrall Soby remarked, "the art of the scuola metafisica was mannered, nostalgic and elegiac, as art can be only when it is brought into being by those who have lived with the dead body of a once great tradition."[1] Guston's irritability roused him only toward an exploration of the other voice he had always heard. There was nothing nostalgic about his struggle with himself during the two years following the Jewish Museum exhibition. He worked. He scraped away. He finished no paintings at all, but he did complete a sheaf of remarkable drawings that were as starkly simple as Oriental characters, sometimes merely a line or two of India ink on a pristine white or cream paper. In these, the splendor of Piero's silence is reflected. They are limpid in light as in that first morning of the world portrayed by Piero in The Baptism. There are no equivocal loops or warps in these drawings. They are stripped down to a most elemental truth—signs of his delicate feelings about light, space, and their sheer intrinsic beauty.

During the two-year span of 1966–67 Guston did literally hundreds of drawings in ink and brush or charcoal on paper. The period remains in his memory as one of conflict:

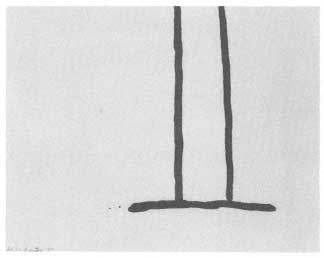

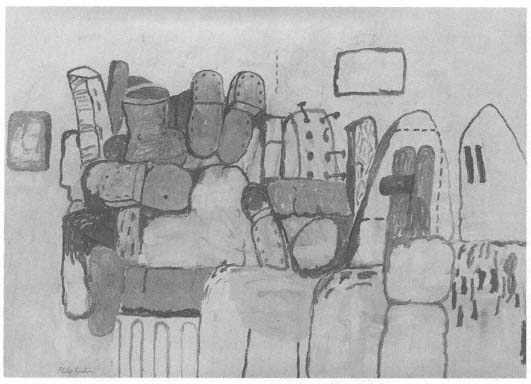

Off Center , 1967. Ink on paper,14

× 16½ in.

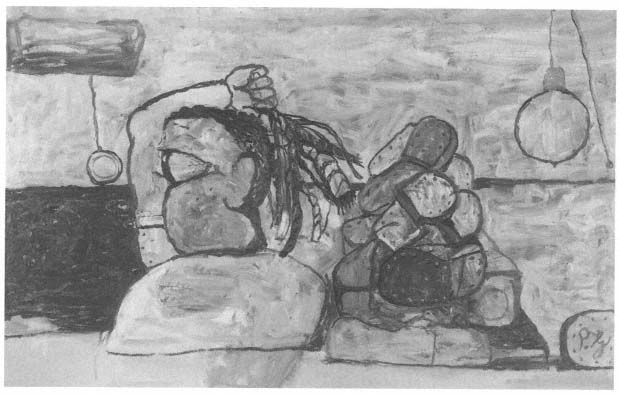

I remember days of doing "pure" drawings immediately followed by days of doing the other—drawings of objects. It wasn't a transition in the way it was in 1948, when one feeling was fading away and a new one had not yet been born. It was two equally powerful impulses at loggerheads. I would one day tack up in the house a bunch of pure drawings, feel good about them, think that I could live with them. And that night go out to the studio to the drawings of objects—books, shoes, buildings, hands, feeling relief and a strong need to cope with tangible things. I would denounce the pure drawings as too thin and exposed, too much "art," not enough nourishment, and as an impossible direction with no future. The next day, or day after, back to doing the pure constructions and to attacking the other. And so it went, this tug-of-war, for about two years.

In this combat, the debate took place on the level of drawing, "not only because one's impulses surface more rapidly in drawing but because the drawings seemed to symbolize the issue."

In 1968 he once again set out to disembarrass himself of his own past, and of his culture, just long enough to establish contact with his canvas. Once again, he did not care to step back. He began to paint with acrylic on small panels, and he painted what he called common objects. In the beginning, they were identifiably books, though more like ancient tablets with incised vertical lines or horizontal ledgers. These books reached phantasmic proportions and metamorphosed into buildings, bread, and sometimes canvases. The old impulse to caricature revived. Guston's "common objects" of 1968 were things huddled on the bottom of an abstract place, or they were exactly and primi-

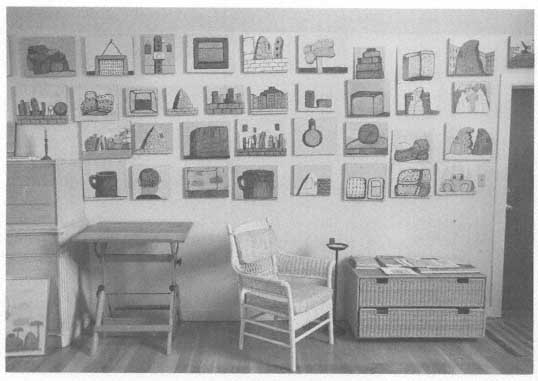

A wall in Guston's Woodstock studio showing several paintings from 1968. (Denise Hare)

tively centered on the canvas. In these initial paintings he retained the emphatic line derived from his drawings, the line that seems to draw itself, unmask, and mock itself. He was impelled to seek that "primitive" urge that Kafka had once found in Kierkegaard. The "objective" realm has become characteristically a realm of grotesques, heavily tinged with irony. Once again, Guston deliberately invoked himself as Eiron —he who knows but pretends he knows not. He initiates an inquiry that soon assumes the proportions of a full-scale drama, always assuming that in his dissembling stance as Eiron, truth through artifice will emerge. Guston's sense of irony led to a reversal of process. He did drawings as once he had done paintings, without stepping back, but he began to "see" paintings in a way that no longer permitted the process to determine the meaning. He had had homeopathic doses of strong emotion, and reached catharis. In 1968 he could say that he did not want "emotion or ambiguity to stick to me like seaweed."

The catharsis was hastened by circumstance. During 1968 there were repeated campus demonstrations against the war in Vietnam, often

reaching dangerous antipodes of mass hysteria. Then there was the Democratic convention in Chicago, with its numerous episodes of violence and its undercurrent of mindless chaos. Isolated in the quiet of Woodstock, Guston watched the television reports of bloodied heads and youths trampled by mounted police, and worried. Worry grew to fury and fury impelled him to make an image. It was then that the ominously detached hand and finger appeared, trailing a column of blood. In this ex voto, recalling so many visual crosslines of twentieth-century angst (de Chirico's impaled gloves: Picasso's distorted hands; the Surrealists' constant play with detached human members, particularly hands), Guston experienced a full resurgence of his youthful outrage. This athletic hand then became a Gogolian protagonist in dozens of small paintings. During the Chicago riots, Guston worked furiously. He painted shoes like buildings, clocks, stony books, buildings like primitive pueblos. Headlike shapes mashed after rioting. Owlish heads, and rapid, choreographed conversations between disembodied hands. Brick walls appeared, reminiscent of his old holocaust allusions to suffocating imprisonment, and with them the familiar hooded figures (not only recalling the Ku Kluxers of his early paintings but also the artists in the scriptoria of the medieval plague years who donned hooded gowns in the vain hope of avoiding the plague). He was off on an irreversible orgy of grotesquerie.

His mood of Ubuism isolated him from the New York art world, but it brought him close to a new friend, the writer Philip Roth. Roth had recently published Portnoy's Complaint, and in the combined flood of literary rebuke and popular success felt himself deeply alienated. He withdrew to Woodstock in 1969 where he established a bond with Guston based on their common need to "depart from our culture." Guston was already well into his new mode and was working on large

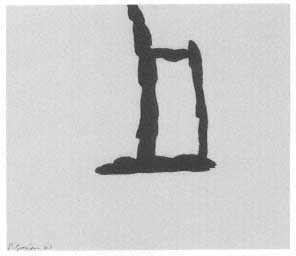

Chair , 1967. Ink on paper, 18

× 23 in.

Hand , 1968. Acrylic on canvas, 18 x 20 in.

oils. He felt he was "onto something" at the time Roth arrived. The only problem, he felt, was time—time enough to paint "all the images and situations that were flooding in on me."

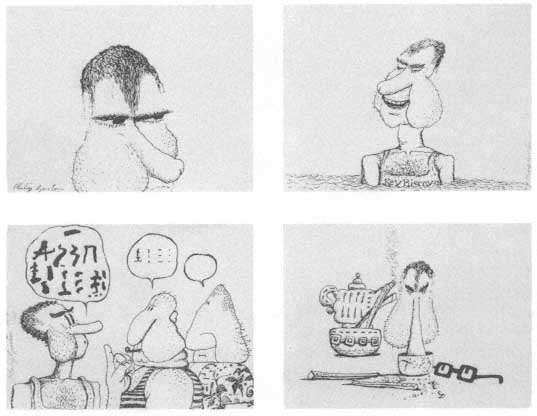

Roth himself with sketching his own burlesque vision of postOswald America at the time, a vision that defied the refinements of the literary world he had grown to despise. "The highbrow dreams of another kind of American image," he says. "When I went to Woodstock in 1969, I felt isolated, lonely. Philip knew about solitude and isolation. But he was rather elated. He had this secret in his studio."[2] The two held long sessions in which they discussed mutual enthusiasms, such as Kafka, who, as Roth says, was "a maniac about being pure," and Flaubert (his letters on fame and loneliness), and the stuff of the newspapers. They had certain past experiences in common—for instance, Roth had once been in Iowa and knew the same haunts that Guston had frequented. He shared Guston's fascination with what the latter called "crappola" and accompanied him to a road emporium to examine "acres and acres of junk." At the same time, Guston, having returned from Europe in the summer of 1971, responded with alarm to the situation in America, and could easily relate to Roth's mood. Roth had embarked on Our Gang, a satire about the dangerously infantile Nixon regime. In the fall Guston was inspired to do a suite of fierce and cunning parodies of Nixon's life.

Guston's elation, which Roth remarked upon, was based on his temporarily successful exorcism of doubt. The image in its "objective" mask now dominated his painting, and he worked with tremendous

Nixon cartoons, 1971. Ink on paper, each 10½ x 14½ in.

enthusiasm. In March 1969, he felt immersed—the condition he always courted and in which he felt most comfortable. He wrote:

Until now, I haven't felt ready—not to prove anything—just to be ready, or rather, to be in a position to feel I have done something worthwhile. This part is difficult, for of course, pictures and thoughts change, evolve, so that like always with me it seems there is only one picture and one frame of mind, the current one. I don't think I've done as much testing of everything I've thought and done as these last few years. It goes on.

I hope I don't sound sentimental but it is so that much of the time what I am painting seems like a mirage to me—a vast detour I am making and I am left with a sense only of my perversity. I must trust this perversity…and yet, who knows I may again be forced to penetrate that state of reduction and essence. But now, the vast complica-

tions and uncontrollability of imagery keeps me in the studio most of the time.

His state of elation led him to wild hyperbole. In April 1969, he was talking about his work in his most Eironlike voice. He had abandoned esthetics, he said. He was only interested in telling a story. "I want to see what it looks like," he said, describing his new paintings of hoods flogging each other, bloody hands, clocks, books. "I'd even do billboards," he insisted. "Who is a painter, after all?" Man is an imagemaker and painting is imagemaking." The abstract painters—what are they telling us? That this is the absolute? Well all right, so is this beer glass. But what else is man? There are many things that move him."

The element of defiance and crankiness in his position was fed by increasingly disturbing events to which he felt he must respond. Guston's thoughts turned back to his youth, when he had watched George Grosz condemn his society, and when he himself had participated in exhibitions sponsored by the activist organization Artists Against War and Fascism. All the while he was warming his outrage in the comradeship of Philip Roth. Roth spoke of his own work as farcical, blatant, coarse-grained. He was interested in the "logic of farce, of burlesque, of slapstick." He felt himself to be the victim of an art-for-art's-sake estheticism, and was struggling to break free much as Guston sought to overwhelm his own innate (and what Roth calls "princely") attitude toward "high art." Roth has described his afternoons reading Henry James, "transfixed by James' linguistic tact and moral scrupulosity," and compared them to the coarse and aggressive clowning of his boyhood evenings at the candy store.[3] This can easily be compared to Guston's preoccupation with Piero, and his contrary interest in the lowlife of cartoons. Roth has candidly stated the problem:

As I now see it, one of my continuing problems as a writer has been to find the means to be true to these seemingly inimical realms of experience that I am attached to by temperament and training—the aggressive, the crude and the obscene, at one extreme, and something a good deal more subtle, and, in every sense, refined at the other.[4]

The subversion of purism is not remote from the subversion of the grotesque, which is generically impure. Another burgeoning friendship during the late 1960s kept alive the other side of the dialogue in

Guston, whose attraction to "the state of reduction and essence" would never be totally expunged. The young poet clark Coolidge, whose work during the late 1960s when he first met Guston was markedly reductive (words disembodied, extracted from context, lining the page with a pristine abstraction opposing the complex syntax of the baroque), began to pay long visits to Woodstock. Coolidge had long been an admirer and a serious viewer of Guston's work. The paintings of the 1950s, such as Zone and Attar, were essential in his own formation; they "incited" him to write. "What attracted me," Coolidge says, "was Philip's feeling for structures, and his doubt. Negative and positive. Things that go together and things that don't."[5] The two also shared literary enthusiasms (Melville, Kafka, Beckett), an interest in the movies, and a measure of splenetic disgust with the world, the art world, the literary world. In a sense, Coolidge extended the long conversation that Guston's friendship with Morton Feldman had initiated. Feldman's addiction to the "absolute" partook of a grand modern tradition of quintessentiality. Coolidge, in his poems of the late 1960s, seemed intent on arriving at a place as remote from quotidian chaos as Mallarmé's void. In his careful structures of words rendered abstract (through the absence of syntactical links and the paucity of verbs) he sought the greatest abstraction of all, which was to become the title of his first published collection, Space. The words, removed from their matrix, fondled, faceted, placed in a "space" that felt right, gather their own momentum. What is true of a Mallarmé poem—that repeated reading discloses forms that can never be precisely transcribed in prose, and never precisely dissected—was true of

Philip Roth , 1973 Ink on paper, 11 x 8½ in.

the poems in Space. In later poems, Coolidge moved closer to Guston, particularly to Guston's drawings. He asked himself, under the painter's influence: What if I were to write "the shoe is on the table?" "I was impressed by the fact that Guston could paint a form that relates to car, lampshade, and shoe, and yet not lose the whole physics of form." Coolidge began to take back the verbs and adjectives he had once carefully excised. Solids began to appear, sparingly, in his poetry. The absolute space of the poem began to be qualified by minor details. One word next to another, as in Guston's inventories of clustered forms, took on extensive meanings that could no longer be mistaken for the purity of "concrete" poetry. Yet Coolidge remains very much in the tradition of "high art." If the mocking tone of the burlesque is in his work, his attitude toward the poem as a thing in itself remains seriously respectful of the "sanctity" of the work. Corrosive humor and quixotic rebellion are quickly appreciated but never endorsed in Coolidge's work. His feeling for "stuff" and for objects is affectionate, his are Bloomsdays rather than the doomsdays that shadowed Guston's isolated years in Woodstock.

Coolidge, who was much involved with Guston's "continual process of drawing," and who has, as he says, a predilection for black and white, saw parallels in his process and in Guston's when they first met. As a matter of fact, Guston's own interest in the incomplete, which holds the promise of completion in its very structure, remained important in his process, even when he stepped into the "realm of the objective." The art of the caricaturist is always abstract, leaving its imperatives in the viewer's imagination. Guston had long been engaged in a kind of truncating process that he sometimes identified with "erasure." In the early abstractions, scraped-out forms that left phantoms were his means. But later, erasure transforms itself into a process of omission. The abstract drawings he worked on in 1968 and 1969 were virtual forms, to be completed by the act of seeing. Coolidge himelf practiced a kind of "erasure" through omission as when he arrays suggestive word-endings on the last page of Space:

erything

eral

stantly

ined

ards

cal

nize[6]

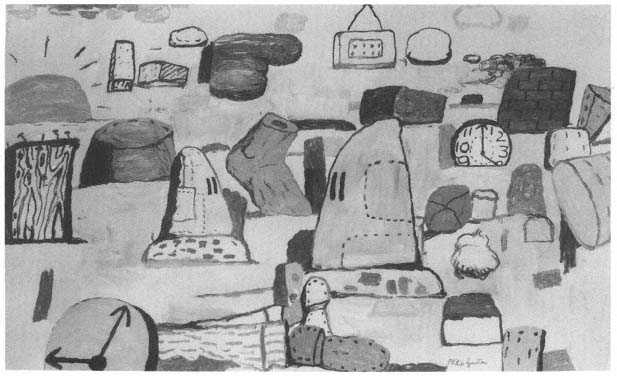

In Guston's drawings from 1969 through 1971 a great deal can be

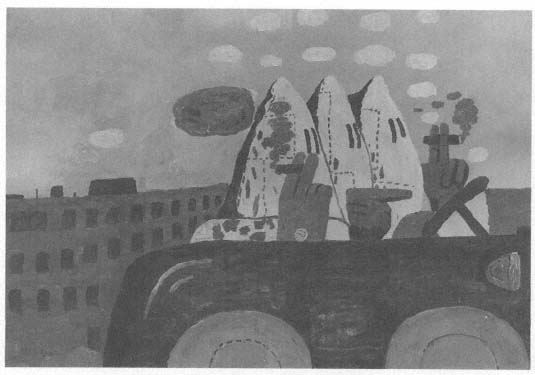

discerned. The range of mood is wide—from comic, affectionate, and tender to downright surly. There he is developing his cast of characters for the grotesque mummery he now "sees" in terms of a long series of episodes. He is telling stories, but he is also refining a vocabulary of forms (the shoes, clocks, and window shades) that he has known intimately all his painting life. In some of the drawings echoes of Krazy Kat predominate (those hot-dog cars with doughnut wheels in which the cigar-smoking hoods cruise). The buildings are represented in comic-strip caveman style. The thickness of the trudging line beckons the thickness of things. But the things are not always explicit. They metamorphose. They make similes. They refuse literal reading. In most of the drawings, erasure yields to emphasis, but never totally.

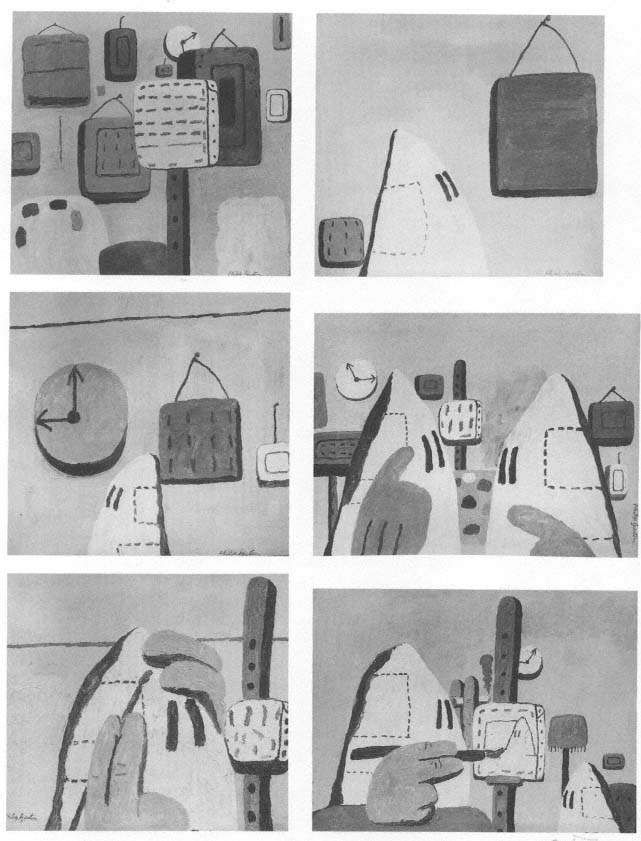

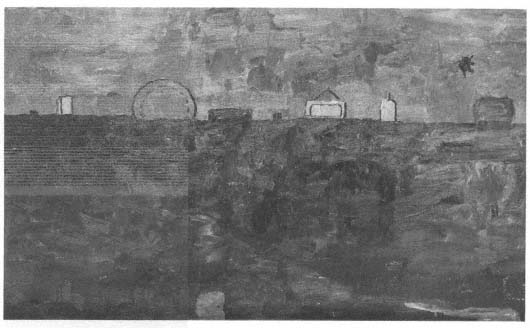

Around 1970 Guston became, he said, a movie director. "I had impulses to do things and motifs—crazy things like brick fights and figures diving into a cellar-hole to 'thicken the plot.'" In his new whitewashed cinder-block studio he filled the racks with narratives, sometimes drawing on old sources (the memory of Italian hill towns for instance), sometimes on actual objects that he had carefully selected in his wanderings in the immediate countryside—old, homely household utensils, tools, tin cups, railroad spikes. Then there were his "characters"—two, sometimes three, hooded figures, smoking, discoursing in various situations. They are seen in an art gallery gesticulating with thick red hands, commenting on paintings that are paintings of themselves. They ride around in their black cars through deserted squares, hauling grainy hefts of wood for their eventual crosses. Godforsaken villages are their

The Law , 1969. Charcoal on paper,

18 x 15 in.

Riding Around , 1969. Oil on canvas, 54 x 79 in.

territory when they are outdoors, but mostly they are encased in their cells surrounded by the stuffed chairs, fringed lamps, and green window shades Guston undoubtedly knew from his youth. Occasionally there would be mounds of pink honeycombed houses, primitive reminders of ancient dramas. The forms are unstable, the gestures exaggerated, the puffs of clouds in the sky derived from the old cartooning days. The hoods transform themselves from outright floggers to art critics (in one picture they stand discussing an all-red painting—Guston's stab at contemporary art criticism), and from art critics to the artist himself, who is seen in several sequences painting a selfportrait. In fact, his identification of himself as a director was accurate enough, and the director he most resembled was Fellini, whose comments in the late 1960s could stand for Guston's:

Once a film is finished it always contradicts me. Intentions, projects, represent for me only instruments of a psychological nature that put me in a condition to realize a film. I have no vocation for theories. I

detest the world of labels, the world that confuses the labels with the thing labelled.…Realism is a bad word.…I see no line between the imaginary and the real. I see much reality in the imaginary.[7]

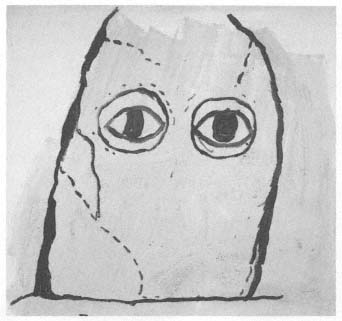

The realities Guston saw, and which were specifically available to the viewers of his Marlborough Gallery exhibition in the fall of 1970, partook of many spiritual experiences, and many sorrows. The socalled mandarin in him was far from yielding to the stumblebum, as The New York Times insisted. For those willing to examine the work closely, there was immense variety and reverberations that went all the way back to the Renaissance, not just to the American comic strip. True, the accents were shifted. Instead of Piero, there is now the unmistakable reference to Signorelli, particularly the apocalyptic frescoes in Orvieto, where Signorelli had filled the vaults with writhing, screaming sinners, portrayed in remarkable diversity. In this eschatological vision, earth colors predominate—siennas, rust reds, dusky oranges, and mossy greens. The shadows are clear, and yet somber, unlike those of Piero. In the midst of the furor, Signorelli stands full and firm, looking out calmly at the spectator, just as in a number of Guston's drawings of hooded figures, the eyes of the artist himself peer out (and still later, with the hood removed, only the eyes are left). Like Goya who wrote "this I have seen," Signorelli places himself as a witness in Hell, as does Guston himself, who once remarked that "Like Babel with his Cossacks, I feel as if I have been living with the Klan, riding around empty streets, sitting in their rooms smoking, looking at light bulbs.…"

There are, among the paintings of 1970, bleak and powerful references to the end of the world and to horrors not even Signorelli could have envisioned. But there are also numerous autobiographical references and allusions to various painting traditions that Guston had long sought to reconcile. In the Western and dialectic history of art, there are always alternatives, as in the case of "genre" painting in the North during the Renaissance and its sharp distinction from the idealizing southern modes. Instinctively Guston had focused on painters who had known similar conflicts. His long interest in Watteau for instance

Six comments on the art world: top left: Wall, 1969. Oil on panel, 36 x 40 in.; top right: Red Picture, 1969. Oil on panel, 24 x 26½ in.;

middle left: Corridor, 1969. Oil on panel, 24 x 26½ in.; middle right: Discussion, 1969. Oil on panel, 30 x 40 in.; bottom left:

The Painter, 1969. Oil on panel, 24 x 26½ in.; bottom right: Painter and Model , 1969. Oil on panel, 30 x 40 in.

A Day's Work , 1970. Oil on canvas, 78 x 110 in.

has been as much based on Watteau's eccentric position to his period as on his painterly eloquence as an "echo" to his period.

Watteau had been reared in the Flemish genre tradition and, when he arrived in Paris, he continued to draw his subjects from the streets. His many sketchpads contain vigorous characterizations of ordinary people, as well as incisive notations of the gestures of the Italian actors in the commedia dell'arte. Many of Watteau's studies of hands suggest his special interest in the balletic and narrative function of gesture best observed in the commedia. Watteau was functioning in a period in which the art establishment (the court) loathed genre painting. But he, and a few others, persisted to the point that a critic complained that "pictures expressing great passions of the soul are replaced by low and coarse works without high thoughts, without dignity, without discrimination. A stable, a tavern, stultified smokers and topers, a cook with all the sordid instruments of her laboratory, a urinologist, a toothpuller: these are the subjects which today delight our connois-

seurs."[8] Watteau was the prototype of the "stumblebum" in his youthful works, and probably in the private works of his last years, long since destroyed. However, the very court that averted its eyes from low-life paintings enacted parodies of low life for its own amusement, as when Louis XIV dressed himself in shepherd's clothes and danced a popular dance. The establishment, at least, saw such painters as Bosch and Brueghel as sources of low comic entertainment. These artists' ascension to the true and timeless grotesque was not noticed in their time.

Yet artists have always sensed the pull of this other tradition in which the follies of mankind appear epitomized and in which the comic subsides once the imagination is engaged in the whole oeuvre. Guston, in his teens, had singled out "a jewel of a Bosch" in his visit to Mexico, and he enacted in his own life certain of the strategies the genre painters employed. Like Brueghel, who is said to have donned disguises in order to participate in the revels of the people he would later paint, Guston had in a sense donned his mask and thrown himself into the life of the streets as a youth. The watcher in him remained distinct from the watched. If at last he paints himself as a grotesque, consisting only of an eye, it is in keeping with the entire tradition of tragicomedy and with its emphasis on irony and alienation. He takes details much as Cervantes did, to persuade us that there is a reality (such as the heavy flatiron or the railroad spikes in his paintings of the 1970s), and then puts them into contexts that persuade us of the irreality of the entire world and the vagaries of the imagination. Cervantes, whom Octavio Paz has called the first great modern writer,

Hooded Self-Portrait , 1968. Acrylic on canvas,

30 x 32 in.

The Deluge , 1969. Oil on canvas, 77 x 128 in.

makes us wander dazedly with Don Quixote through landscapes that seem real but are spread out in crazy-quilt patterns that cannot be real. Paz contrasts Don Quixote with Dante's Paradiso and Inferno, which are "real, just like Florence and Rome" while the "grisly reality of Castile is a mirage, a piece of witchcraft." In Cervantes

there is a continuous oscillation between the real and the unreal: the windmills are giants, and a moment later they are windmills again. This oscillation doesn't alter anything: people are condemned to being what they are.…Men are no less problematic than things and both than language.…Language is no longer the key to the world; it is a mad word, void of meaning. Or is the opposite true? Is it the world that is mad and Don Quixote the word of reason travelling the roads in the guise of madness? Cervantes smiles: irony and disenchantment.[9]

Guston's retrieval of the tradition of the true grotesque is seen not only in the ostensible motifs (which like the windmills can turn with lightning speed into other hidden motifs before our eyes) but in the very mode of "locating" them. These inventories of things—huddled

together or adjacent to one another or clinging like barnacles to still larger things—are filled with the chaos of Castile as Don Quixote knew it, an aimless and disorienting place in which there are queer symmetries or no symmetries at all. The disguised forms weave their narratives in disjointed terms always favored by the masters of the grotesque, including Goya, Ensor, Beckmann, and others Guston had seriously considered. The witness, Guston, shifts his feet rapidly to get another view, and in so doing, becomes another witness. Who, in fact, is this witness? And from what point of view does he tell his tale? Guston often refers to the Japanese film Rashomon, in which several witnesses offer widely divergent accounts of the same event. He is himself all the witnesses in these late paintings and, though their messages seem clear at first glance, they quickly dissolve into perturbing riddles of existence filled with the same anxiety that had prompted his dark paintings of the 1960s.

Flatlands , 1970. Oil on canvas, 70 x 114½ in.

The Desert , 1974. Oil on canvas, 72½ x 115½ in.