Accessories

Sash.

—A brocade sash (p1.31)is worn by the men who take part in public ceremonies. Each sash is made up of two "panels of plain weaving of cotton or wool, decorated at the end with designs in colored yarns and terminating with a fringe".[54] Two-thirds of each panel is plain-woven; then the heddles of the loom are adjusted to work the pattern in yarn. At the point where this decoration begins, a finer weft is used so that the addition of the colored yarns does not widen the cloth. The designs are virtually alike, being made up of bands of black, green, and blue with a red diamond design in the center. At their plain ends the two panels are sewn together with a roving of cord. This produces a long sash which can be wrapped about the waist and knotted on the right side with the ends hanging to the calf of the leg. The origin of the sash appears to be unknown, but the form was fully developed in the earliest modern examples collected by James Stevenson in 1879.[55] The sashes are brocaded today with commercial yarns; "however, old specimens show hand-spun wool for both the body of the sash and the brocading".[56]

The plaited white cotton sash with its long fringe is one of the most significant and potent of rainmaking garments. "A typical example of the sacred sash is composed of 216 threads of white cotton about the size of small package cord braided into a band eight inches wide and sixty-one

Plate 21.

Animal impersonation. Buffalo Dance, San Ildefonso.

inches long to the termination of the solid braiding. The work is started midway of the cords when a twining is applied temporarily, and proceeds toward either end when the cords are divided into twelve tresses braided into narrow tapes for a short distance".[57] Over each tape end, rings of cornhusk wrapped with cotton cord are slipped and tied in place. The cords are then divided into sixes and twisted together to form a long fringe, which symbolizes, in the Indian mind, the falling of the rain in its long, parallel lines (pl. 20). These sashes are kept clean and white by rubbing with liquid kaolin.

Belt.

—The woven belt, ordinarily worn by the women around their everyday dresses of dark wool, became a part of the ceremonial costume because of its usefulness and its striking colors. Walter Hough remarks that "the greatest play of fancy in the Hopi textile art is the weaving of belts".[58] In this article of apparel there could be produced small and greatly varied patterns not limited by ceremonial rules (fig. 10, p. 58).Woven on an easily manipulated small loom, warp threads to form the designs could be picked out by hand. "The warp and weft are often of the same yarn, giving uniformity of texture, but usually the warp is partly of yarn of the same thickness as the weft yarn and partly smaller. This arrangement furnishes a fertile field for the play of design. The warp in the central or pattern band of a belt is generally of small white yarn and another color of larger yarn, usually red, the former working out white pattern grounds, having raised figures in red warp, the latter contrast being produced by the difference in size of the yarns, the small warp being worked singly and the larger in pairs".[59] The use of small and large warps gives an uneven surface to the material and is the only example in Pueblo weaving in which this method of obtaining variety is found. The most prevalent color scheme is composed of a wide center of red broken by black designs and edged with two stripes of green which in turn are bordered by two narrow lines of black. Other combinations show a red center with white designs, a black and red stripe, and a final line of white on each side; or

a red center with white patterns, a stripe of blue-green, one of ultramarine followed by one of red, and a final edging of white. The patterns are manifold geometric forms made up of small triangles and with lines repeated in different and varying combinations.

The women wear this belt wrapped several times around the waist, drawn in tightly, with part of the loose fringe tucked under a lap so that the rest falls down on the left side. The brilliant color of the belt is a conspicuous accent on the dark garment (pl. 1). The width varies from three to five inches and the tight wrapping helps to confine the figure. The men dancers use this belt to hold their kilts in place or to encircle their bodies over the brocaded sash. When worn in the latter fashion, one part is looped over and the fringe of the two ends hangs to the middle of the calf of the leg. In the Peace Dance of the Tewa, which depicts a combat between chiefs of opposing forces, "a description of the battle which brought peace to the tribe",[60] the wife of each chief appears holding one end of a belt which is fastened to her husband's waist. The significance of this is that behind all warfare the ties of family and home life are vital incentives to valorous deeds.[61]

Foxskin.

—A noticeable feature of many of the costumes is the pendent foxskin, worn tail downward at the back of the belt (pls. 24, 35). This particular fox, formerly indigenous to the mountainous country of the Pueblos, is a small animal with gray hair intermingled with amber. It was hunted during the season of the year when the hair was long and thick and the hide tough. When killed, the body of the animal was skinned very carefully and all the parts were retained: the paws remained on the legs, and the ears were kept on the full head covering. Ruth Bunzel says that the foxskin tail is "considered as a relic of the earliest days of man, for the katcinas were transformed while mankind was still tailed and horned".[62] For several days previous to each occasion on which they are worn, the pelts are buried in damp sand in order to bring suppleness to

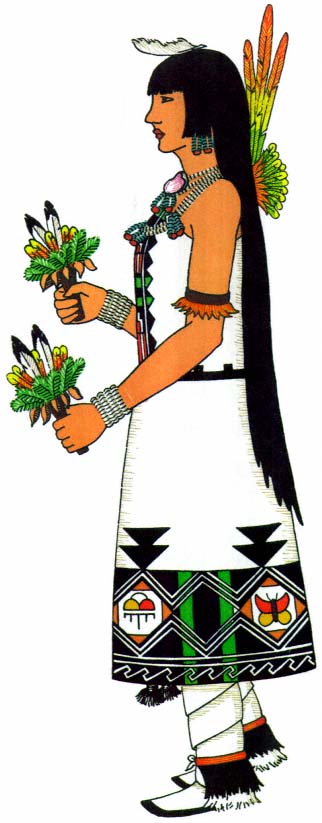

Plate 22.

Women's costume. Buffalo Dance, San Ildefonso.

the skin and a soft, live quality to the fur. In most of the ceremonies the men dancers wear foxskins. This custom evidently carries for the Rio Grande Pueblos no association with animal tails, for none of their hunt impersonators wear them, but, instead, affect the fringes of the plaited sash (pl. 26) or a fan of eagle feathers (pl. 23) on the belt at the rear. The Hopi and Zuñi animal impersonators wear pendent foxskins, but not as animal tails; their use by these performers conforms entirely to the conventional kachina dress.

Bandoleers.

—Many kinds of bandoleers are worn over the right shoulder, and at the same time they encircle the body to the waist on the left side. The more common and concededly less potent kinds are broad bands of ribbon,[63] beadwork from the plains, red woven belts,[64] twists of yucca cord or leather and cedar berries. Conch shells (Conus ) strung on thongs or yucca cord are highly prized for their rarity.[65] "Warrior katcinas wear the bandoleer of the bow priest over their right shoulder. This is made of white buckskin, decorated with fringes under the left arm and ornamented with a zigzag pattern of shells, four for each scalp taken. A little of the hair from each scalp is sewed into the broad fringed portion. The bandoleers of the bow priests hang by outer doors of their houses. They are never taken into back rooms. They must always be removed before going into the room with the corn, or before drinking, lest the spring from which the water was drawn be contaminated.[*] The bandoleers of the bow priests may be borrowed or imitated".[66] Double bandoleers are also worn, hanging from each shoulder and crossing on the chest and back.[67] Impersonators concerned with the hunt often have pouches suspended, like the bandoleer, from the right shoulder (pl. 5). They are similar to those which "hunters use to carry their animal fetishes and prayer meal".[68]

Jewelry.

—Above all else among his purely private and individual possessions, the Pueblo Indian prizes his jewelry. Apparently he has done so

* The enemy are supposed to be very dangerous and often are witches who weave magical spells.

from the earliest time. Archaeologists have unearthed many smoothly turned disks of stone and shell pierced with a hole in the center for the purpose of being strung on thongs of deerskin. Furthermore, great numbers of crude beads and pendants have been found, which undoubtedly were worn as necklaces and earbobs by the prehistoric men who lived in cliff houses and communal towns.

The Indian first used as jewelry whatever was near at hand of a decorative nature. Seed pods, acorn hulls,[69] the teeth and bones of animals picked up promiscuously and perforated and strung together to be hung about his person—these were the early and crude expression of this intimate kind of ornamentation. As his culture evolved, his amazing capacity for painstaking labor developed new forms of beads from the more precious materials. Soon he was not only adorning himself with the graywhite sea shells obtained from the far Pacific or from the scintillating waters of the Gulf, and with the reddish coral brought back by runners from their trading expeditions into Mexico, but was also decking his neck and arms and ears with ornaments made of the brilliant turquoise with its matrix of soft brown. This was mined from the rough stretches to the east of the Rio Grande and to the south of Zuñi. Beads were also made from the chunks of lignite and the dull pink quartz which crumbled from the outcroppings along the rocky ridges.

Many kinds of shells were used as bead and ornament. The small, barrelshaped olive shell (Olivella ) with its tapering ends and the tiny conch with its reducing spiral could be strung together one after the other on necklace or bandoleer, or tied to buckskin and fabric as tinkler and fringe. Multitudinous flat shells, either whole or in part, were brought into use as bead and pendant. The larger, oval abalone shell (Haliotis ) was often hung at the base of the neck, where its iridescent, pearly inner surface gleamed softly against the rich brown tones of the skin (pl. 21).

With its piercing blue, the turquoise reflects the power and glory of the daytime sky from which come life and beauty in the warmth of the

purifying and nurturing sun and the repose of the rain-bringing and shadowing cloud. Turquoise is the most highly prized of the Indian gems, and it has been worn throughout the entire historic period of Pueblo life; in the records of the Coronado expedition it was noted that the Pueblo Indians wore turquoise in their ears "as well as on their necks and on their wrists".[70] Moreover, it has value as an economic investment, At Zuñi, "after the sale of wool in the spring a man liquidates his debts and invests the balance in turquoise".[71]

Figure 19.

Rotary drill.

The bright, soft red of the coral is used to offset and intensify the beauty of the turquoise. Thus the Indian is able to combine two natural elcments which complement each other in color an dequal each other in tone value.

Since the earliest times, small disk-shaped beads have been made by the Pueblos. In excavations and ruins many examples of exquisite workmanship have been found. The process by which these beads are now made is as follows. The material is roughly chipped out to a little more than the desired size, and then a hole is bored in the center with a drill pump. This is a device like the spindle, with a flywheel on a long, slender shaft. A stone or metal point is attached to one end, and at the other two buckskin thongs support a crosspiece with a large hole in which the shaft may move freely. The buckskin thongs are twisted around the shaft, and the point of the drill is placed in the center of the bead and made to revolve by a pumping motion with the crosspiece, while the flywheel produces rotation which unwinds the thongs in one direction and rewinds them in the other. The bead is drilled halfway through from one side and then is turned over and the drilling is completed. Shell beads require but few strokes, whereas turquoise, jet, and

coral require much drilling. When a number of rough beads have been drilled, they are strung in a tight column on a length of cord and the whole string is ground to an even size on a slab of sandstone or between two stones.[72] The beads are then sorted and matched by color and size, and strung in necklaces of one, two, or even four strands. White shell is often interspersed with small symmetrical beads or large, rough chunks of turquoise, and short strings of turquoise with a few beads of coral are looped over the long strands and bunched together at the bottom. These same small strings of turquoise are sometimes tied with thongs in the ears and from this position peep from beneath the black, bobbed side hair.

Another form of jewellike decoration is the mosaic pendant, delicate and of beautiful design. Mosaics consist mainly of small, flat pieces of turquoise, coral, quartz, and jet set together in simple patterns. Their base is the softly curving back of a clamlike shell or a glittering piece of jet, to which they are glued with piñon gum.

When the Spanish colonists came, silver was introduced to the pueblos. For a long time this new material had little or no effect on the Indian, and then suddenly there sprang up a remarkable silver-working industry. This was dominated by the Navaho.[73] Today the foremost jewelers among the pueblos are the people of Zuñi and Santo Domingo. Here, round silver beads, and occasionally the conventionalized silver squash blossoms, are strung into necklaces terminating, like those of the Navaho, in a curved pendant set with turquoise. Turquoise and the soft, rich silver are used together in a hundred patterns. "The Zuñs are freest in combining these two elements; with them a silver bracelet is hardly more than a setting for fine, deep blue stones".[74]

Silver earrings are shaped to resemble the dragonfly, the butterfly, or some bird, and all are set with turquoise. Silver and turquoise rings are ubiquitous, as jewelry is worn by all: men, women, and children. Proud is the mother whose baby wears about his neck a string of tiny turquoise

Plate 23.

Realism in bird impersonation. Eagle Dance, Rio Grande.

beads, or on his arm a little silver bracelet. "The amount of turquoise worn by an impersonator is limited only by his borrowing capacity. The necklaces cover the whole chest, frequently also the whole back.... The way of wearing the necklaces is indicative of rank and position. Necklaces front and back indicate a Katcina of importance; necklaces doubled over and worn close to the throat are a badge of society membership."[75]

Sun-disk ornament.

—A disk surrounded by feathers is the most prominently used of the separate ornaments. It symbolizes the sun and often has stylized features painted on its buckskin face. Sometimes the disk is a round bunch of gaily colored feathers, and the diverging rays are reduced to a few long shafts of brilliant colors across the top (pl. 22); at others, the entire circumference is decked with the severe black and white of the eagle wing feathers shot through with long, waving strands of red horsehair.

A similar disk is fastened to the end of a pole and used in kiva rituals when the ceremony has to do with the sun. It is raised, lowered, or twirled as the action in the rite demands."[76]