Image versus Text

in the Illustrated Novels

of William Makepeace Thackeray

Judith L. Fisher

British book illustration in the nineteenth century can be neatly divided into two periods: from 1800 to mid-century, Isaac and George Cruikshank and Phiz and Thackeray drew on Hogarth's allusive and allegorical representations and on the great caricaturists James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson to create "speaking" pictures. From the 1850s on, primarily through John Everett Millais's illustrations of Trollope's novels (but also through secondary artists such as Richard Doyle, who illustrated Thackeray's Newcomes and Frederick Walker, who illustrated Adventures of Philip ), a style deriving from English genre painting emerged that increasingly subordinated the image to the text.[1]

My use of the term "subordinated" suggests one significance of this stylistic shift and explains why we no longer expect novels to be illustrated. Once an illustration simply reinforces the text, it can easily dwindle into mere decoration—as it does in the ornamental style of Kate Greenaway. Thus illustration came to be identified with light literature and children's books (where, interestingly, the significant image is reviving in the work of such artists as Maurice Sendak).[2] The caricatural style offered its reader-viewers an additional narrative voice, making the image as important as the text. This seeming parity incited some volatile exchanges between illustrator and writer, as when Cruikshank claimed that his illustrations were the germ and genius of Dickens's Oliver Twist and William Ainsworth's Tower of London .[3] The Cruikshank-Dickens quarrel, pursued after Dickens's death by Cruikshank and John Forster (Dickens's friend and biographer), illustrates the uneasy marriage of the caricatural style and the novel. Caricature takes liberties: the impudent pen of the artist exposes the foibles of the familiar subject. Cruikshank's

determination to maintain his artistic independence is not surprising, considering that he was an established caricaturist before he started illustrating novels.

The case of Thackeray is different, more interesting, and ultimately more suggestive. Here is an artist who developed as caricaturist-illustrator and novelist simultaneously. J. H. Stonehouse's catalogue of Thackeray's library, compiled for its auction in 1864, describes book after book as containing Thackeray's "illustrations" or "caricatures "in the "spirit" of the text. Thackeray drew in everything, from Fielding's Joseph Andrews to Baedeker's Handbuch für Reisende in Deutschland, und dem Oesterreichischen Kaiserstaat —as if he could not read without seeing .[4] As illustrator of his own works, Thackeray saw the relation between image and text as a self-conscious dialogue, emphasized in the subtitle of Vanity Fair, "Pen and Pencil Sketches of English Society." The drawing between chapters nine and ten of the "narrator" unmasking dramatizes Thackeray's self-awareness—the face of the melancholy fool behind the mask is Thackeray's own (Fig. 22).

The nature of the dialogue between text and image varied; as J. R. Harvey, Joan Stevens, Patricia Sweeney, and others have noted, the illustrations add metaphorical comment, extend the story, alert the reader to significant patterns, and supply visual types for the characters.[5] Thackeray's most successful illustrations, aesthetically and interpretively, do not "illustrate" the text at all.[6] The illustrations to Vanity Fair, The History of Pendennis, and The Virginians and the pictorial capitals in The Adventures of Philip create alternative story lines, presenting countervoices to Thackeray's narrations.

These countervoices encourage self-conscious seeing/reading in the ways they speak against the text and among themselves. Often the illustrations do not conform to any one convention of representation: they are both mimetic and metaphoric. Martin Meisel describes Thackeray's style as a synthesis of opposites, "uniting a concrete particularity with inward signification, the materiality of things with moral and emotional force, historical fact with figural truth, the mimetic with the ideal" (36). As the reader shifts between text and contrasting image, the interpretive options multiply, allowing simultaneous but diverse meanings. The eye cannot move to the illustrations for a confirmation of the story because the illustrations both fix an image and evoke interpretations beyond those contained in the language. Thus, while contemporaries such as Henry Kingsley called Thackeray's illustrations "a key to the text," they function less to unlock what is in it than to galvanize the reader's own interpretive abilities.[7] Ultimately, to read Vanity Fair, Pendennis, The Vir-

ginians, or The Adventures of Philip without Thackeray's illustrations is to read a novel other than the one Thackeray intended and to lose one of the great pleasures a Thackerayan novel offers: moving between word and image, the reader shares the narrator's ability to manipulate the story.[8]

Thackeray most closely follows the tradition of subordinating image to text when his illustrations evoke sympathy but avoid sentiment.[9] The "eye of sympathy" gives us a character's visual perspective and, without words, creates a sudden understanding of an emotional state. An intratextual illustration early in Vanity Fair works strongly to create sympathy for Amelia by showing us what she sees when she visits George's house before her father's bankruptcy. Chapter 12 criticizes the two Miss Osbornes' and Miss Wirt's disdainful dismissal of Amelia by showing us the unsympathetic women she sees (Fig. 23). The text above reads, "And this day she [Amelia] was so perfectly stupid and awkward that the Miss Osbornes and their governess, who stared after her as she went sadly away wondered more than ever what George could see in poor little Amelia" (100). The reader, however, seeing the unsympathetic, harsh faces that Amelia sees, automatically agrees with the narrator's comment below the illustration, "Of course they did. How was she to bare that timid little heart for the inspection of those young ladies with their bold black eyes?" The illustration—much more hostile than the narrator—suggests just how unyielding Amelia finds the Osbornes.

While the untitled intratextual illustrations are drawn in a nonmetaphoric, mimetic mode, they do not simply reinforce the text. The "eye of sympathy" that modifies our reading by giving us a sudden understanding of how a character sees, giving us that character's perspective, can suddenly reverse our involvement with the character and thrust us out of the text. The intratextual illustration that introduces Lord Steyn in chapter 37 acts against the text to create a shock that further reflection transforms into ironic surprise (335–36). In the first edition, at the bottom of the recto page, the reader is treated to the description of Becky arranged as an artwork:

The fire crackled and blazed pleasantly. There was a score of candles sparkling round the mantelpiece, in all sorts of quaint sconces, of gilt and bronze and porcelain. They lighted up Rebecca's figure to admiration, as she sate on a sofa covered with a pattern of gaudy flowers. She was in a pink dress, that looked as fresh as a rose; her dazzling white arms and shoulders were half covered with a thin hazy scarf through which they sparkled; her hair hung in curls round her neck; one of her little feet peeped out from

the fresh crisp folds of the silk: the prettiest little foot in the prettiest little sandal in the finest silk stocking in the world. (335–36)

The reader's eye then moves to see what Becky is seeing: Lord Steyne, who has been innocuously introduced previously as her audience: "The great Lord of Steyne was standing by the fire sipping coffee" (Fig. 24). Steyne's leering, loutish appearance contrasts sharply with the "dainty" language of Becky's picture. The effect is to reveal the deceitfulness of Becky's art—a disguise that now seems obvious in the language itself. The overuse of diminutives and superlatives ("little feet," "prettiest little loot," "prettiest little sandal," "in the world"), the hackneyed simile "fresh as a rose," the slip in taste suggested by the "gaudy" flowers on the sofa argue that the narrator wants us to question the sincerity of this picture. The juxtaposition of illustration and text jolts us into questioning the entire value of Becky's picture making. If this is her audience, can her art be genuine? Both Becky and Steyne are morally discredited: Becky by preening for such a man and Steyne by exhibiting his brutal nature. Thackeray's use of the word "great" to describe Lord Steyne recalls Fielding's redefinition of it to describe Jonathan Wild; Thackeray had explored the redefinition in "Caricatures and Lithography in Paris."[10] An instinctive revulsion from Steyne makes readers reassess Becky's efforts as they are described. The antagonism between image and text allows readers to recognize how they, too, can be drawn in by Becky's art. Readers are thus both alerted to Becky's machinations and made aware of her potency.[11]

Such interaction between text and illustration often turns a simple sketch into a metaphoric "realization." I exclude from this category overtly symbolic illustrations such as the pictorial initial in chapter 61 of Vanity Fair, where the cluttered hearth with no fire, slippers carelessly flung, and doll (puppet?) on the mantelpiece symbolize John Sedley's death. Such drawings are independent of the text and create their own iconography from the details of daily life. Quite different are illustrations that seem to be simple reifications of the text but which become symbolic as the reader/viewer moves between text and drawing. A clear example of this is a simple intratextual illustration of the Chevalier Strong blacking his boots in volume 2, chapter 23, of Pendennis . On the same page he refuses to procure yet another loan for Clavering because he has given his word to Lady Clavering: "the Chevalier said that he, at least, would keep his word, and would black his own boots all his life rather than break his promise" (2:227). Only in this context does the

drawing become an emblem of Strong's integrity, in sharp contrast to the intratextual illustration of Clavering begging money from Altamont in the preceding chapter. The essential characters of the two men are crystallized in these pictures, which become "signs" of their moral quality.

Patterns of such "signs" develop as tacit commentary that gradually builds a consistent counterpoint to the text. In chapter 25 of Vanity Fair, Becky, Rawdon, George, and Amelia are at Brighton, and Becky and Rawdon are in the process of fleecing George. The intratextual figure shows George and Rawdon at cards, with Becky standing at George's shoulder, gazing down with a sly smile (212; Fig. 25). On the preceding page, the narrator had given us another word picture of Becky: "She was looking over her shoulder in the glass. She had put on the neatest and freshest white frock imaginable and with bare shoulders and a little necklace, and a light blue sash, she looked the image of youthful innocence and girlish happiness" (211). This Becky is depicted in the full-page illustration "A Family Party at Brighton" opposite the intratextual (Fig. 25). In this combination of text and illustration, then, Becky's knowing expression undercuts her "innocence." The intratextual figure, following the narrator's description of Becky's watching "kindly" over George while he plays écarté, actually shows her sly calculation. The text hints at its own disagreement with the representations when the narrator describes Becky "fixing on a killing bow." Her "kindly" look is actually a "killing glance," just as her bow is both hair ornament and sexual weapon—as her reference to George as "Cupid" also suggests. Thus Becky is "betrayed" by the illustration, in which her sly smile emphasizes the irony of the narrator's descriptions of her kindness and anticipates the destructiveness of her flirtation with George.

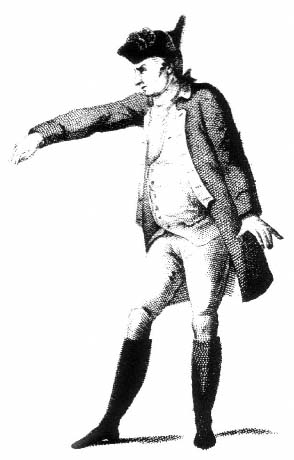

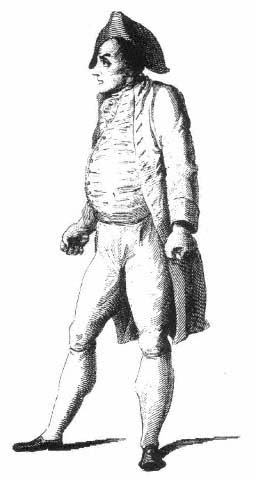

In fact, Thackeray's famous ambivalence about Becky is partly resolved for the reader of an illustrated text. By either offering information omitted in the text or actually countering the text, as in the illustrations in chapter 25, the illustrations of Becky betray her posturings and undermine the narrator's excuses. She is consistently portrayed as a sharp-featured, narrow-eyed woman, as in the illustration at the end of the first number, "Mr. Joseph Entangled," where her face resembles that of number 32 in Henry Siddons's Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action (1807).[12] Throughout the novel, Becky is visually represented as either "False Gesture" (Fig. 26) or "Menace" (Fig. 27; number 29 in Siddons), sharing the slanted eyebrows, narrow eyes, and aquiline features of these figures. The continuity of the expression acts as an independent piece of information for readers, telling them not to be deluded

by their own impulses to sympathy and warning them not to accept either Becky's or the narrator's justifications of her actions, for example, "if she did not get a husband for herself, there was no one else in the wide world who would take the trouble off her hands" (17). We see her first leaving school with this wicked smile and next at the Sedleys, while in the meantime the narrator has asked us to accept her as a "picture of gentle unprotected innocence, and humble virgin simplicity" (emphasis added, 19). Obviously something is askew because the only picture the reader sees is that of the conniving Becky, as in chapters 7, 17, 25, 36, 67. The consistency of Becky's representation would have reminded readers of each monthly installment of the "real" Becky, but it would also have keyed for them passages of narrative irony. Ultimately, this consistent value-laden image encourages an ironic reading of passages that do not necessarily invite ironic reading, or even a denial of the narrator's description. The illustrations force the reader to ironize the narrative, especially because the other characters are taken in by a face that readers cannot see as honest or attractive. Moreover, this consistent representation suggests that to a discerning eye Becky's nature cannot he disguised. In a brilliant touch of irony, Becky the expert actress (or mimic) is visually "shown up" by Thackeray's pen, which transfers interpretive power to the reader, especially in the absence of an overtly ironic text. The narrator's ambivalent attitude toward Becky does not align with the consistently hostile representation of her. Readers must determine for themselves how to interweave the visual and the verbal.

Becky's self-deceit is betrayed when the illustrations present information she neglects. Just as Rawdon, George Osborne, and the younger Sir Pitt are blind to Becky's nature, Becky's only perspective is that of her own self-flattering mirror. Her two letters to Amelia in chapters 8 and 11 show us her blindness. In the letter in chapter 8 Becky describes going in to dinner without mentioning her scowling face and scolding manner (Fig. 28). The reader sees this missing information, but Amelia does not; thus we are early alerted to Becky's selective perception. While Becky's omission here is deliberate, her ignorance of Mrs. Bute's plot is just that—ignorance fostered by her own vanity. Becky reports her dance with Rawdon to Amelia as a triumph while the reader clearly sees it as Mrs. Bute's scheme. The irony is emphasized when Becky includes her own drawings of her rivals (Fig. 29). She has an acute eye but no peripheral vision, so to speak.

Such consistent representation and recurring patterns of juxtaposition between images and between images and words are visual dialogues, which develop into voices echoing that of the narrator, not really

outside the text but not totally embedded within it. As the images become more overtly symbolic, as in the pictorial capitals, they become more independent of the text. Joan Stevens describes the narrative function of the pictorial capitals in particular as predictive, "foreshadowing events, offering generalized comment on the action, embodying by means of a traditional reference the basic moral implications of what lies ahead, or, at a shallower level, adding a simple visual dimension to forthcoming words" ("Thackeray's Pictorial Capitals," 116). However, the illustrations—initials, intratextuals, and full-page—also function retrospectively and accumulate meaning. Some of the patterns they establish have already been noted by Robert Colby and Joan Stevens ("Thackeray's Pictorial Capitals," 126–28), who have followed the military motif in Vanity Fair from the equestrian statue on the cover to Becky as Napoleon in chapter 64, including the various mock "campaigns" in text and illustration.[13] Catherine Peters has also noted the recurring motif of church and home in the background of outdoor scenes in Vanity Fair .[14] Both the military and religious patterns reify textual metaphors—for example that of Becky the "intrepid campaigner" as Napoleon.

These visual metaphors offer comments on the story not acknowledged by the narrator. Patterns such as the equation of Becky with Napoleon visually unify the chapters and bridge the monthly parts. John Harvey, in Victorian Novelists and Their Illustrators (84–86), and Joan Stevens, in "Thackcray's Vanity Fair" (30–31), both note the continuity and comment between numbers 4 and s in Vanity Fair, where the image of "Love on his knees before Beauty" in chapter 15 alludes to the intratextual figure of Sir Pitt on his knees before Becky in chapter 14. The ironic image ending number 4 contrasts with the initial to chapter 15, which shows a young boy worshiping at the altar of Love while an imp peers around the initial E (128–29). What Harvey and Stevens do not note is the subtle play between word and image and the connotations of "picture." Becky and Sir Pitt are carefully positioned beneath portraits: Pitt beneath an eighteenth-century profile, Becky beneath an imprecise image of a woman whose expression recalls Becky's usual scowl—absent in this case. The text under the tableau, "Rebecca started back a picture of consternation," which at first seems to suggest that this scene is contrived, is followed by the line that says Rebecca "wept some of the most genuine tears that ever fell from her eyes" (128). The very sincerity of Becky and Sir Pitt aligns with the falsity suggested by the pictures. Sir Pitt's lust is not love, and Becky's consternation is caused by her losing a fortune, not a lover. Again, the illustration subtly betrays her, like those

linking numbers 2 and 3 in chapters 7 and 8: number 2 closes with a vignette of a little girl building a house of cards, and number 3 opens with an image of Becky gazing at the portrait of Sir Pitt's first wife (64–65). The point is clearly the futility of Becky's ambitions. A similarly ironic commentary connects chapters 10 and 11: the caricature of the swain wooing the shepherdess emphasizes the falsity of the "Arcadian Simplicity" of life at Queen's Crawley (84). The historiated initial which opens chapter 12, the first chapter in number 4, continues this parody of Becky and Rawdon, as the mile marker and the swain's finger signal the departure from "Arcadia and those amiable people practicing the rural virtues" (97).

These examples of illustrations that unify chapters and parts fit into larger visual patterns that develop throughout the novels. Pastoral love in eighteenth-century costume in Vanity Fair and Pendennis, children in Pendennis, the theater and puppets in Vanity Fair and Pendennis, and the narrator-as-clown echo the verbal "languages" of literary conventions discussed by John Loofbourow.[15] Like the illustrations that betray characters, these patterns act as an ironic mirror, turned outward from the story to show us alternative truths of character and event. The motif of children in the chapter initials of Pendennis suggests the characters' lack of control while manifesting the authorial control that produces the visual coherence of the sequence. For example in the text concerned with the death of Helen Pendennis (numbers 18 and 19, volume 2, chapters 17 to 21) the initial W in chapter 18 depicts a priest reading in a graveyard while a gravedigger ominously plies his trade in the background. Although the chapter relates the continental holiday after Pen's illness, the initial prepares the reader for Helen's death. The implicit prediction becomes visual reality in chapter 19, whose initial O contains Helen dead in bed with a Bible on her chest. Chapter 20 shows Pen sitting at a table with the lawyer handing him Helen's will, and chapter 21 suggests Pen's immaturity, his lack of self-knowledge, in a gruesome illustration of two children—Pen and Blanche?—playing cat's cradle on Helen's grave. The realism of the illustrations in this sequence accords with the somber subject, but the final metaphoric initial offers ironic perceptions unavailable to Arthur Pendennis, who is diminished and controlled by this ironic "mirror" of his efforts.

Thackeray's "ironist's mirror" constantly reminds readers that they are reading one version of a story. The narrator's assertion in Vanity Fair that "the world is a looking glass and gives back to every man the reflection of his own face" (9) denies the traditional role of the artist's mirror: to reflect empirical reality. Perhaps that is why Thackeray described the

glass he turned outward on the world as "warped and cracked" and advertised Vanity Fair as "brilliantly illuminated with the Author's own candles" (xiv).[16] Thus Thackeray's clown looks at his own reflection because the external world, represented by the characters and story, is reflected and illuminated by the "lamp" of the author's ego (Fig. 30). In fact, Thackeray's "clown" in the 1848 title page is not a clown at all; he is wearing the costume of a fool or jester, closer to that of the pantomime harlequin. Moreover, Thackeray's draftsmanship is ambiguous enough to suggest that the fool in motley sees himself in a cracked mirror. Thackeray's mirror was "cracked" because he knew his imaging was no true reflection. Not only does a mirror show you images backward; but also how you hold it determines what you see.

The motley fool of Vanity Fair is not the only character trapped by his mirror. The two illustrations juxtaposed in the Garland edition (but not in the first edition) are the Fool and the drawing of Becky finally revealing George as a shallow fool: she shows Amelia his letter, written before he went to battle, asking Becky to run away with him. Amelia has already written Dobbin, asking him to return; nonetheless, this revelation shatters her idealized image of George. And this triumphant Becky has defeated herself by her own fixed perspective, starting as early as those youthful letters to Amelia. This juxtaposition connects the story to the narration of the story. Just as Amelia's idealized image of George traps her in a version of reality that reflects her romanticism but not George's character, so, too, the narrator can only tell a story that is a version of the way he sees the world.

Vanity Fair 's true Narcissus is George Osborne, who opens chapter 13 by gazing at himself in a looking glass over which is superimposed a massive "I"—emblematic of his egotism and closed perspective (104; Fig. 31). But this emphatic "I" is actually the narrator, who perforce is also egoistic and reminds us of the gazing fool on the title page. Thus mirrors in Thackeray's illustrations suggest that all representations are ultimately self-representations. And in fact the narrator's attempts at absolute "truth" are undermined by illustrations that visualize narrative uncertainty. Vanity Fair, Pendennis, and The Virginians all contain illustrations that parody the narrator's sources of information: letters, rumors, gossip, and eyewitnesses.

The image of the clown undercuts narrative stability to hint at an escape from solipsism. To move from mirror gazer to harlequin is to escape from an illusion of stable reality that ultimately imprisons individuals in their own gaze or self-fashioning and into the manipulation of their own interpretations of reality. Individuals may still be isolated,

but they have more power, and, if they wish, they can create illusions of Community—as Thackeray's narrator does between himself and his "friendly" reader.[17]

Pendennis dramatizes this process. Pen changes from a self-absorbed mirror gazer to melancholy fool: or from character to narrator. Pen's first essay in public dandyism, in chapter 18 of the first edition, is marked by Thackeray's illustration of him admiring himself in his academic robes in his tutor's mirror:

he put the pretty college cap on, in rather a dandified manner and somewhat on one side, as he had seen Fiddicombe, the youngest master at Grey Friars, wear it. And he inspected the entire costume with a great deal of satisfaction in one of the great gilt mirrors which ornamented Mr. Buck's lecture room. (1:167)

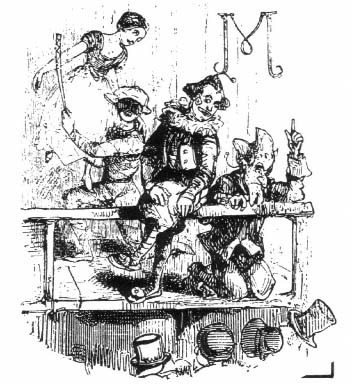

In volume 2, chapter 16, Pen ends this first, sexual, phase of his would-be writer's narcissism when he resists the temptation to seduce Fanny Bolton. Appropriately, his thwarted desire consumes him in an actual fever—Thackeray here makes wonderful use of his own brush with death while writing Pendennis . He has to have his head shaved and, in ironic counterpart to the earlier illustration, the intratextual figure shows us Pen "sadly contemplating his ravaged beauty" (2:148) in a small mirror on his dressing table. Pen's social vanity is thwarted in much the same way; his honor will not let him accept the fortune and seat in Parliament his uncle's blackmail has obtained for him. If he marries Blanche, it will he in a small, plain way. The ironic reward of such integrity is to become the fool. Pendennis ends with a visual harlequinade—not referred to in the text—that illustrates Pen's entry into the world of the ironist. Pen moves into the pictorial capitals (heretofore reserved for metaphoric comment), a literal and symbolic movement out of the boundaries of "story" and "event." Pen's discovery of his own acting during the course of the novel is visualized in his appearance as Harlequin, which disqualifies him as "character," lifting him from the fixed perspective of those who do not know they are "acting" in a story to the detached, ironic perspective of narrator. Pen's last illusion is one that he actually recognizes as an illusion: his election campaign for the seat of Clavering. While the reader, aware of the Major's blackmail, which makes the seat available for Pen, knows more than Pen at this point, Pen does know that his election antics are theater. The "consummate" hypocrisy of Pen "acting" to gain people's favor (2:269) is not mimetic theater but pantomime—extravagant and self-aware theater that transforms ordinary life into fantasy. The initial to volume 2, chap-

ter 27, depicts the traditional pantomime characters Harlequin, Clown, Columbine, and Pantaloon on the hustings, parodying the conspiracy between actors and audience who act the part of not acting (Fig. 32).[18]

When the masked harlequin of the election in this chapter unmasks in chapter 34, he is easily recognizable as Pendennis (Fig.33). Harlequin-Pen, whose costume echoes that of the 1844 pantomime Harlequin Crotchet and Quaver; or, Music for the Million, gazes questioningly at a masked lady as if asking her whether she too will unmask and what will be revealed when and if she does. The "D" encasing Harlequin-Pen and the lady begins Pen's letter to Blanche, asking her to drop her mask of romance. Harlequin-Pen here holds the magic bat, which has the power to transform all the characters in the harlequinade. Pen no longer wears his mask because he knows enough not to believe in his roles. He has discovered that his ambition to shine as an M.P. was founded upon his uncle's blackmail of Blanche's stepfather. To retain the honor he has prized all his life, Pen must settle for a more limited private life. But his triumph is to transform himself without bitterness and to see the humor of his own self-deception. "He laughed to think of how Fortune had jilted him, and how he deserved his slippery fortune. . . . It amused his humor; he enjoyed it as if it had been a funny story " (emphasis added; 2:332). The narrator's term "story" tells us Pen is starting to turn his own life into a text—and any reader familiar with Thackeray knows that for him this is the basic process of fictionalizing. Paradoxically, Pen acquires the clear-sightedness that will make him an author by recognizing that acting is inescapable but that one can choose one's roles.

The initial to volume 2, chapter 35, interprets for us Blanche's inability to emerge from her roles (Fig. 34). The lady has unmasked, but Harlequin has been superseded by Clown, recognizably Pen's rival, Henry Foker. The intratextual figure that follows depicts a "discovery scene" straight from melodrama. Pen refuses his assigned role, however, and simply laughs once again at his own gullibility and Blanche's scheming. His laughter, the irony of his conversation with Blanche, and his eventual willingness to be cast as the villain demonstrate his confidence in an identity that exists independent of others' expectations. In pantomime Harlequin, unlike the clown, wields the magic bat that can transform himself and others—just as the narrator controls his story or the manager his puppets. Harlequin masked is an anonymous actor, subject to the story like any other puppet or stage character, but unmasked he is the melancholy moralist who tells a tale. The harlequin image is Thackeray's developed image of the Vanity Fair clown-as-narrator.

Harlequin without his mask is known to present a very sober countenance, and was himself, the story goes, the melancholy patient whom the doctor advised to go and see Harlequin—a man full of cares and perplexities like the rest of us, whose Self must always be serious to him, under whatever mask or disguise or uniform he presents it to the public.[19]

This sequence places Pen and the narrator in and outside the tale, unable to escape from their perception of the story because that story is their perception. Pendennis complicates the relation between appearance and self because Pen unmasked will become Thackeray masked.

The fool preaching to other fools on the title page of Vanity Fair does not suggest this same edge of ironic control. Donald Hannah describes Thackeray as "both puppet-master and one of his own puppets, pulled by the same strings, actuated by the same motives which animate his own figures."[20] But the puppet frame was conceived toward the end of the serialization; it was an afterthought, not part of Thackeray's original plan. Without this frame, the fool seems less in control, especially when compared with a possible model for this engraving. An engraved scene from the 1844 pantomime Harlequin Crotchet shows a clown lecturing "on soap suds." Although he does not stand on a barrel, the clown is elevated above his crowd and is behind a washtub. In composition the two works are very close. The self-consciousness of pantomime is suggested less by this title page than by the famous sketch of Thackeray "unmasked" at the end of chapter 9. But the clown illustrations in Vanity Fair only imply authorial power. The clown balancing on the W in chapter 27, the clown leading the parade of clowns in chapter 40, and the clown on stilts being rocked by another clown in chapter 49 connect the narrator to the characters more than to the reader or to the narrator's modes of telling. More self-conscious about authorial control is the initial to chapter 2, showing a boy and girl peering into a peep show, which suggests the writer's power to manipulate what the reader sees. The egoism of such control is clearly the focus of the narrative "I" above the sketch of George looking in the mirror in chapter 13. But while subjective perception is an entry into "reality," it is never a definitive entry, and this uncertainty is depicted in chapter 37, where the clown balances the narrator's "I" on his nose (Fig. 35). The "I" that tells us the story is unstable because it cannot be sure of what it tells.

Subjective modes of knowledge such as letters, reading, and gossip characterize Thackeray's narration—and his illustrations emphasize the parallel between the epistemologies of characters and narrator.[21] Jones at his club in chapter 1 of Vanity Fair, Pen hearing himself in print in

volume 1, chapter 36, and the Major in the same chapter reading the Pall Mall Gazette —all image readers' own reading. Rawdon and Dobbin reading the letters we have just read in the text draw readers into the perspective of the characters but cannot counter the general ironic distance (chapters 15, 42). The servants listening to Amelia play the piano (chapter 4), Briggs and Firkin overhearing Sir Pitt proposing (chapter 15), Gumbo lying about Harry's wealth (chapter 16), and Parson Stack gossiping about George and the Indian woman (chapter 55) in The Virginians parody the narrator's culling of information and our own interpretive activity as readers who make our own stories from the bits and pieces we are given.

The self-consciousness evinced by the illustrations in Pendennis tells us that even when Thackeray seems to offer a more stable and conventional narration than in Vanity Fair, he still looks askance at his own story The resulting "story" is incomplete and untrustworthy because image and text destabilize each other. A process of reading and seeing evolves that compels readers to endlessly revise what they have read and seen. Readers become aware of the interpretive strategies they apply to create stable stories and thus realize how much "story" depends upon interpretation. The tension between image and text constantly warns readers about the danger of self-deception—their own as well as the characters', "the dangers of creating from half-sight a self-flattering version of the world."[22] The deliberate contrasts between image and text and the presence of metaphoric patterns argue that Thackeray intended his readers to read self-consciously. Paradoxically, the incomplete "versions" of characters and events that constitute a Thackeray novel free readers from entrapment in their own web of interpretations. Ultimately, to read a Thackeray novel without its illustrations is to miss the imp looking over your shoulder, holding a mirror to your own reading.

Fig. 22.

W. M. Thackeray, The Narrator unmasked,

Vanity Fair (1848), chapter 9.

Reproduced by permission of Garland Publishing, Inc.

Fig. 23.

W. M. Thackeray, Amelia and the Miss Osbornes, Vanity Fair (1848),

chapter 12. Reproduced by permission of Garland Publishing, Inc.

fig. 24.

W. M. Thackeray, The great Lord Steyne, Vanity Fair (1848), chapter 37.

Reproduced by permission of Garland Publishing, Inc.

Fig. 25.

W. M. Thackeray, A friendly game of cards

and "A Family Party at Brighton," Vanity Fair

(1848), chapter 25. Reproduced by permission of

Garland Publishing, Inc.

Fig. 26.

M. Engels, "False Gesture," from Henry Siddons's adaptation

of Engels's Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture

and Action, 1807. Photograph courtesy of Elizabeth Coates

Maddux Library, Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas.

Fig. 27.

M. Engels, "Menace," from Henry Siddons's adaptation

of Engels's Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture

and Action, 1807. Photograph courtesy of Elizabeth Coates

Maddux Library, Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas.

Fig. 28.

W. M. Thackeray, Going in to dinner, Vanity Fair (1848), chapter 8. Reproduced by permission of Garland Publishing, Inc.

Fig. 29.

W. M. Thackeray, Mrs. Bute's scheme and Becky's rivals, Vanity Fair (1848), chapter II.

Reproduced by permission of Garland Publishing, Inc.

Fig. 30.

W. M. Thackeray, "The Letter before Waterloo" and The Fool and his mirror, Vanity Fair (1848),

frontispiece and title page. These illustrations were not juxtaposed in the first edition; "The Letter

before Waterloo" was near the end of the novel. But this placement does capture the

narrator's ambivalence toward his story. Reproduced by permission of Garland Publishing, Inc.

Fig. 31.

W. M. Thackeray, George and his beloved, Vanity Fair (1848),

chapter 13. Reproduced by permission of Garland Publishing, Inc.

Fig. 32.

W. M. Thackeray, On the hustings, The History of Pendennis (1850),

vol. 2, chapter 27. Photograph courtesy of Elizabeth Coates Maddux Library,

Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas.

Fig. 33.

W. M. Thackeray, Dear Blanche, The History of Pendennis (1850),

vol. 2, chapter 34. Photograph courtesy of Elizabeth Coates Maddux Library,

Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas.

Fig. 34.

W. M. Thackeray, Pen's harlequinade, The History of Pendennis (1850),

vol. 2, chapter 35. Photograph courtesy of Elizabeth Coates Maddux Library,

Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas.

Fig. 35.

W. M. Thackeray, A delicate balance, Vanity Fair (1848),

chapter 37. Reproduced by permission of Garland Publishing, Inc.