PART II—

THE CHURCHES

Santa Fe

San Miguel

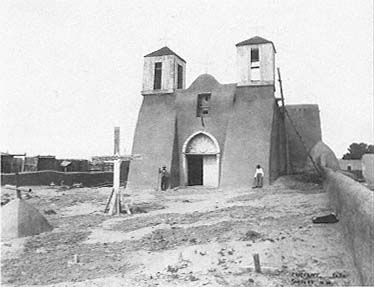

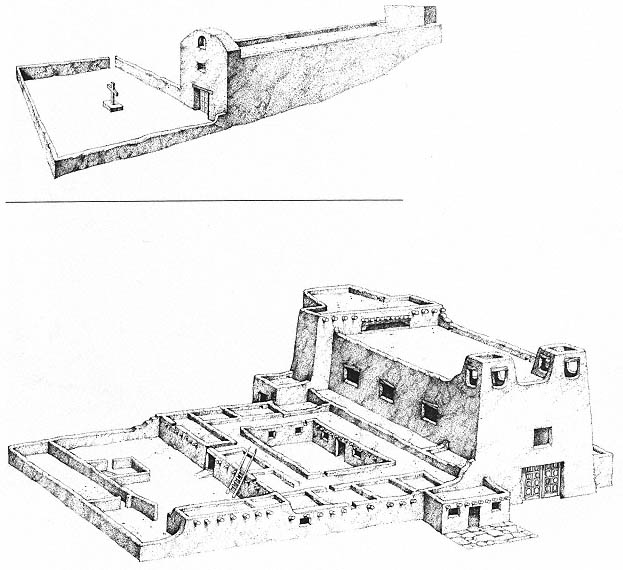

pre-1628; 1693–1710

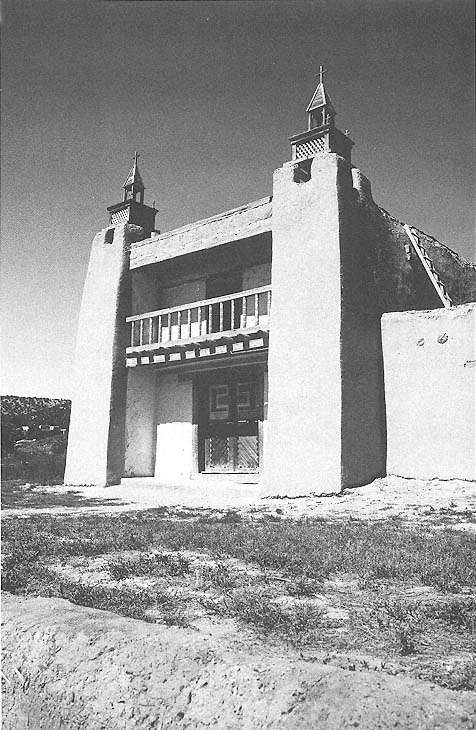

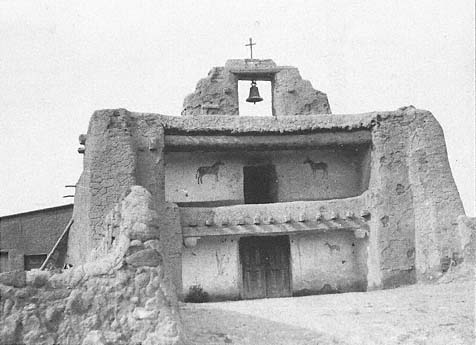

As a member of the family of New Mexican churches, the chapel of San Miguel is an anomaly in several respects. Its primary congregation was neither the Europeans of Santa Fe nor the Pueblo Indians, but the Indian servants who accompanied the Spanish as they pushed colonization and Christianization north into New Mexico. As a physical form the church today is unique, being capped by a single tower in contrast to the more typical flat-faced and twin-tower arrangements. Only in its interior arrangement does the chapel follow the common mold characterized by a single nave, tapered sanctuary, transverse clerestory, and choir loft.

The first mention of the ermita of San Miguel appeared in a document dated July 28, 1628, in which Governor Felipe de Sotelo Ossorio was charged with "impious conduct during the mass."[1] Hence by that date a chapel already existed, constructed sometime after the provincial capital was transferred to Santa Fe south from San Gabriel in 1610. The site for the chapel lay on the opposite bank of the Santa Fe River apart from the formally planned and plotted part of Santa Fe. The Barrio Analco, as the district was known, was a piece of land settled by the Indians who had accompanied the Spanish as allies and intermediaries. The site shows signs of Indian occupation from the fourteenth century, as evidenced by remains found during excavations under the chapel in 1955 by Stanley Stubbs and Bruce Ellis.[2]

Tradition has it (although without documentary evidence) that a portion of the barrio's residents were Tlascalan Indians from Mexico who had been granted special dispensation by the king because they had allied with the forces of Hernán Cortés in the Spanish battles against the powerful Mezo-American tribes. As a result, they were exempted from paying certain taxes and were allowed to bear European arms. The Spanish also used them as colonial liaisons: to undertake negotiations on behalf of the Europeans and to set an example in farming and mining techniques. They worked, Marc Simmons noted, as colonists, miners, soldiers, and assistants to Spanish explorers and missionaries going north.[3] Although the Pueblos conformed more closely to the Spanish concept of civilization and thus had less need of models, some Tlascalan Indians might have accompanied Oñate's expeditionary forces in 1598. It is believed that at least one Franciscan in the party brought with him a Tlascalan assistant.[4]

Although relatively highly regarded by the Spanish, these Indians were not considered as equals and worked as menial help for the Spanish settlers of

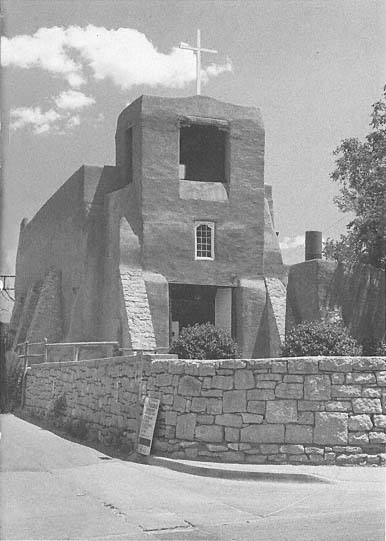

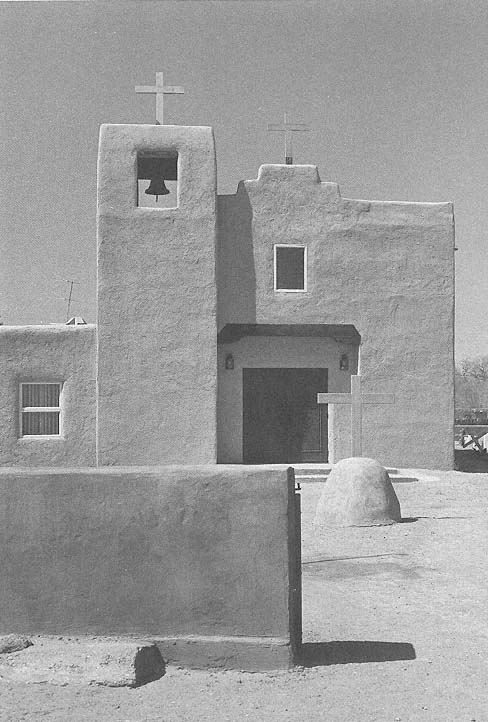

2–1

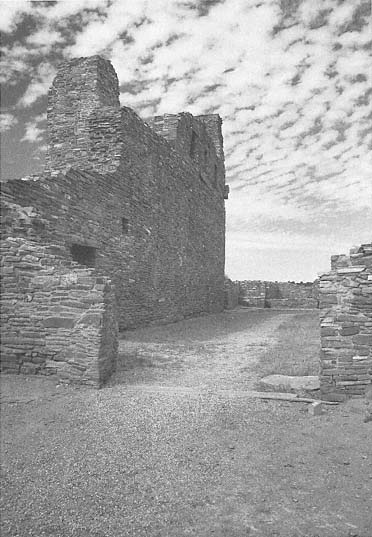

San Miguel

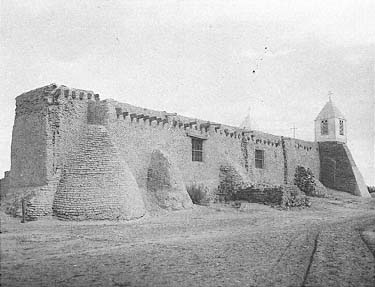

The church in its current form, a curious mixture of stone buttresses,

a single tower, and an oversized void.

[1984]

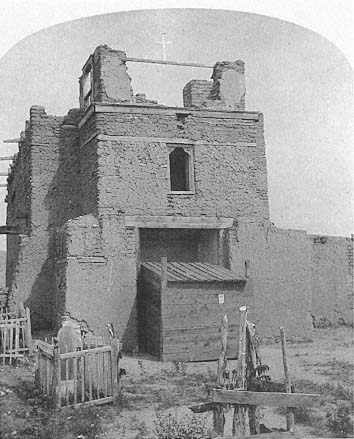

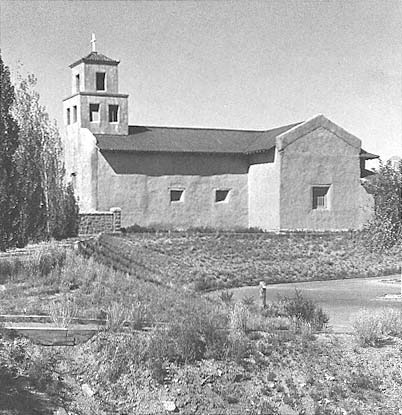

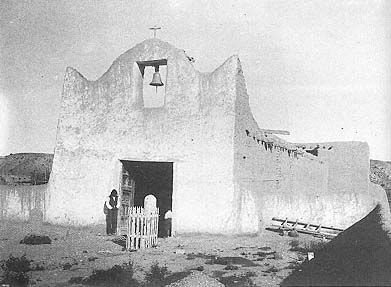

2–2

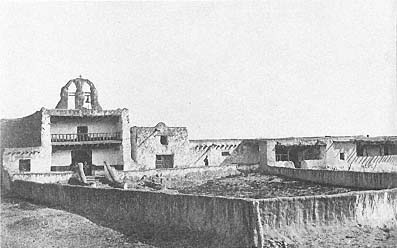

San Miguel

1872–1873

Late in the nineteenth century the five-level tower grew from a solid

earthen base.

[Timothy O'Sullivan, Museum of New Mexico]

Santa Fe. Consequently they settled the land analco , a Nahuatl (language of the Tlascalans) word meaning "across the water" or "on the other side of the river." Whether the barrio's original inhabitants were specifically Tlascalan or were simply other peoples from Mexico has been the subject of some debate. In either case, by 1640 the Barrio Analco was considered a viable community by the Spanish, as evidenced by a document in the General Archives of the Indies. Benavides wrote that "it [the villa] lacked the principal thing, which was the church; that which they had being a poor 'jacal'; because the Friars first gave their attention to building churches for the Indians whom they converted, and among whom they lived and labored; and therefore as soon as I became Custodian, I began to construct the church and convento to the honor and glory of God."[5] One may infer from this statement that the ermita de San Miguel was the first religious structure constructed by the Spanish in Santa Fe, a rather curious occurrence considering the attention given to the formal planning of the town. The construction of the first parroquia followed the completion of the Indian chapel across the river. The 1628 document that cited the governor's misconduct indicated that the Spanish were still using the chapel as their parish church through the late 1620s and early 1630s.

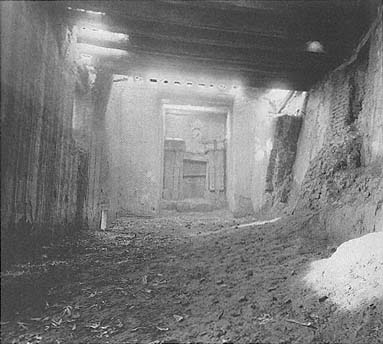

Little is known of the first edifice that occupied the site. Excavations in 1955 by Bruce Ellis and Stanley Stubbs revealed several layers of construction beneath the floor of the current church. The older chapel, believed to have been built sometime before the Reconquest and possibly before the pre-1640 church, was smaller than the present-day building, with a narrow, rectangular apse in place of the current angled walls and a sanctuary raised two steps above the nave. The facade was probably planar, with neither towers nor buttresses.

Relations among the civil authorities, the military, and the clergy were frequently stormy, and in the late 1630s, with the governorship of Luis de Rosas, the trouble was brought to a head. Attempts to resolve the problems had been in vain. When Fray Bartolomé Romero and Fray Francisco Núñez were sent to Santa Fe in 1640 to meet with the governor and attempt a reconciliation, he verbally abused them, beat them with a stick, and had them imprisoned. The friars were later released, but the church was closed and its bells removed.

The culmination of the disputes between church and state was the razing of San Miguel in 1640, the adobes presumably taken down with the vigas and reused in other construction. The drama did not end with demolition, however. Late one night Ni-

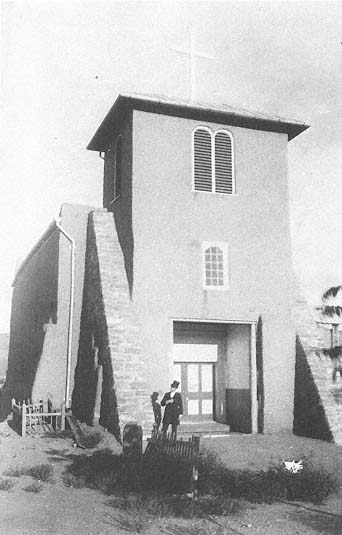

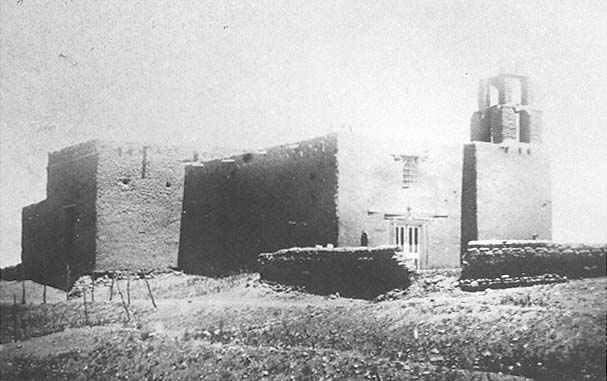

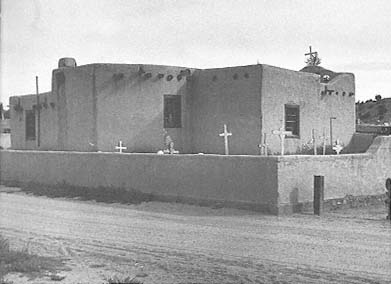

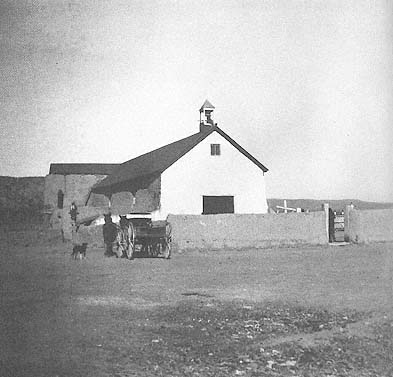

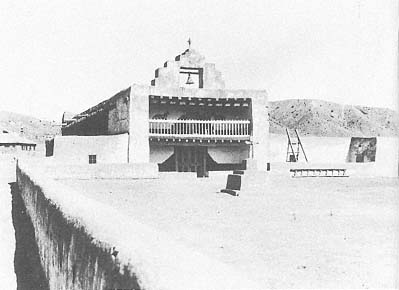

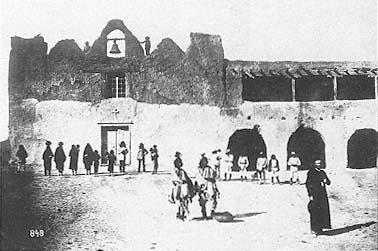

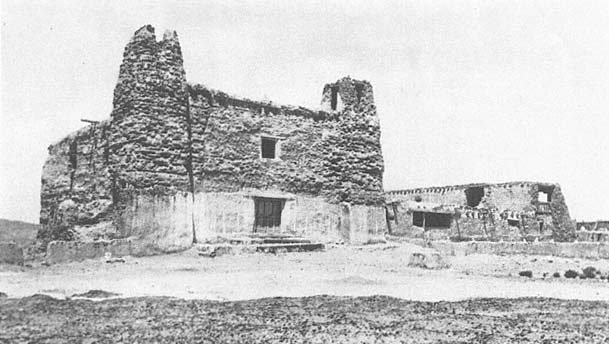

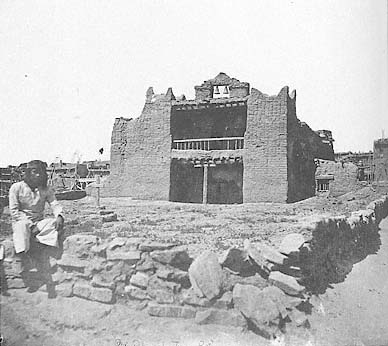

2–3

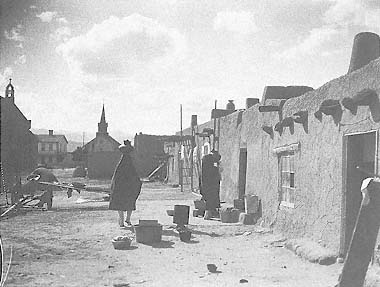

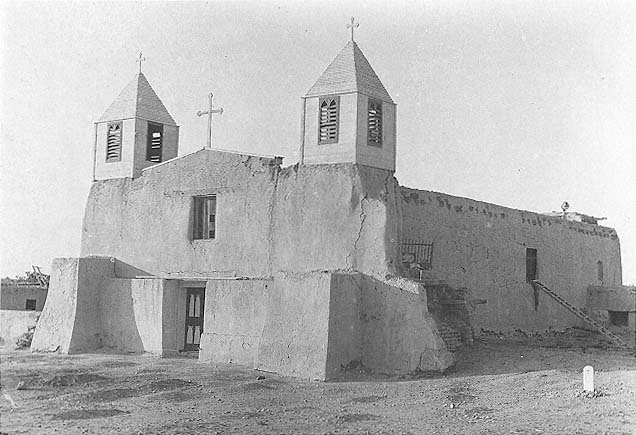

San Miguel

circa 1880

The chapel in derelict condition, the upper stages of its stepped

tower had vanished. Note the embedded timber used to reinforce

the adobe construction.

[F. A. Nims, Museum of New Mexico]

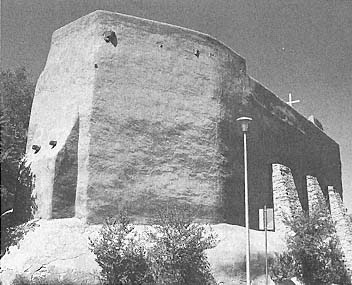

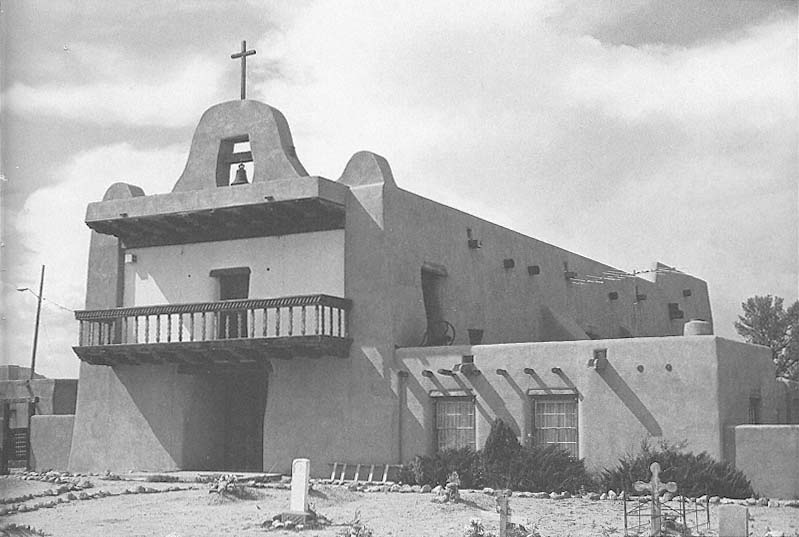

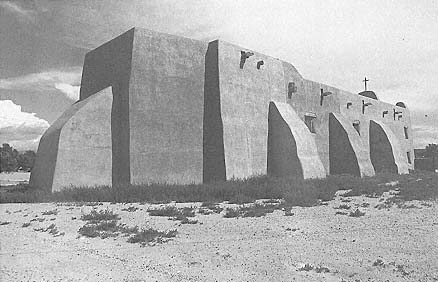

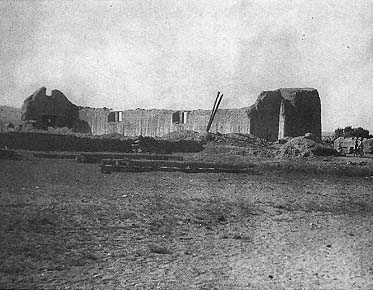

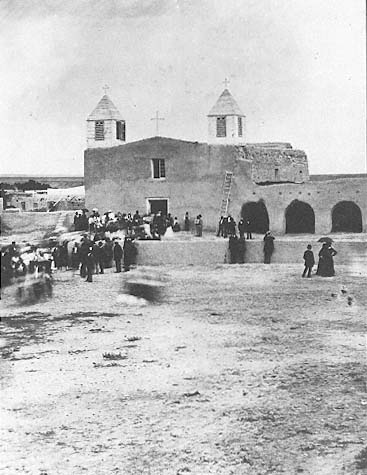

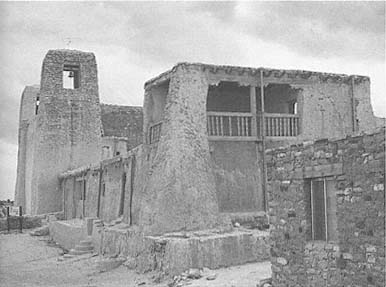

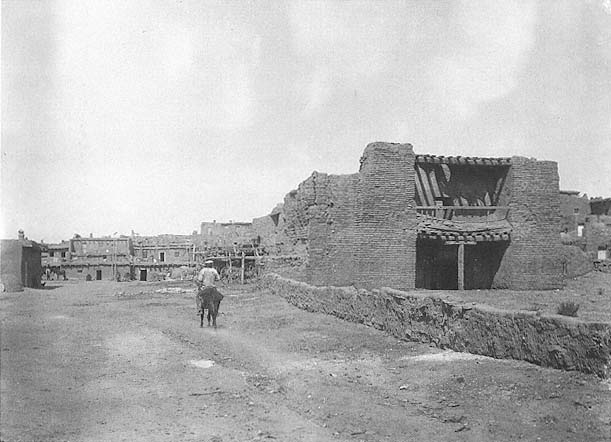

2–4

San Miguel

circa 1884

A single, more massive tower has replaced its staged predecessor;

stone buttresses strengthen the facade.

[Dana B. Chase, Museum of New Mexico]

colás Ortiz discovered his wife in Governor Rosas' house, which precipitated a turmoil that resulted in the murder of the excommunicated former governor some weeks later. Rosas was absolved of his activities against the religious by a priest named Juan de Vidania, who was arrested later by the Inquisition but escaped while en route to Mexico. This complex, fascinating, and bizarre chapter in New Mexican history brought into high contrast the chronic antagonisms within the civil administration and the church as well as those between church and state.[6]

Although the church was subsequently reconstructed, the new structure did not last long. Burned during the Pueblo Revolt in 1680, its shell remained unused for the next twelve years. The report issued by Diego de Vargas on his return to Santa Fe made no mention of a need for new wall materials, so it is assumed that only the wooden superstructure required replacement. Vargas, on inspecting the burned church, instructed the people "to roof said walls and to whitewash and repair its skylight in a manner that shall be the quickest, easiest, briefest and least laborious to said natives."[7] In December 1693 men went to the mountains to cut vigas but turned back after several days because of the extreme cold.

The poor condition of the chapel must have upset some members of the congregation, not the least or least noble of whom was Alférez (which corresponds to second lieutenant) Agustín Flores Vergara. In a request to the custos, Flores wrote, "I beseech and entreat his reverence to grant me permission to go about in this city and in other territories of this kingdom, with the holy image, to make a collection of alms which will be of assistance in the execution of the chapel, in order to locate the image therein."[8] He presented this to the custodian, who, Kubler told us, "instantly grant[ed] his request." The history of San Miguel from that time on, at least in terms of politics and ownership, was much calmer.

The repair or major renovation of San Miguel is discussed in great detail in George Kubler's Rebuilding of the Chapel of San Miguel . Ensign Flores had raised the funds for the repairs and had hired fifteen workers to execute the work, although none seems to have been Indian.[9] By calculating the number of adobes needed to repair the walls, Kubler figured their height at about seven feet, although archaeological investigations in 1955 were unable to ascertain whether this estimate was correct. It is believed that the change from the rectangular to angled apse dates from this period, as do the two niches in the

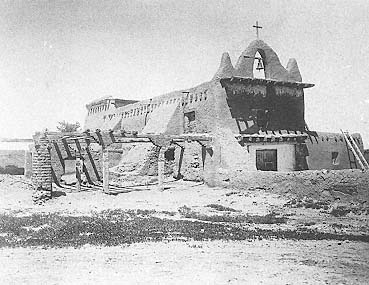

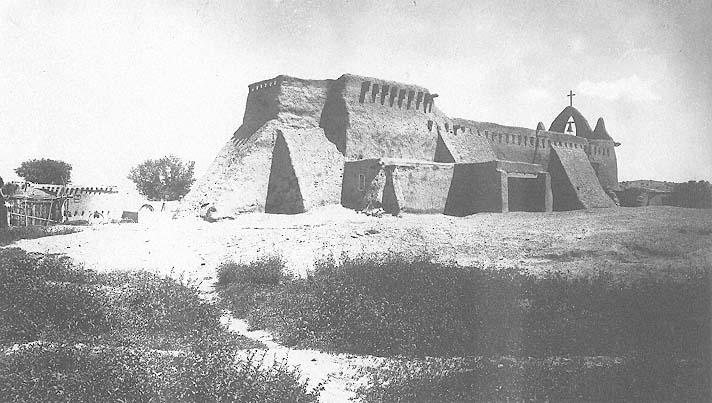

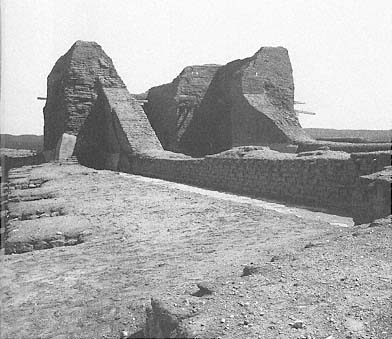

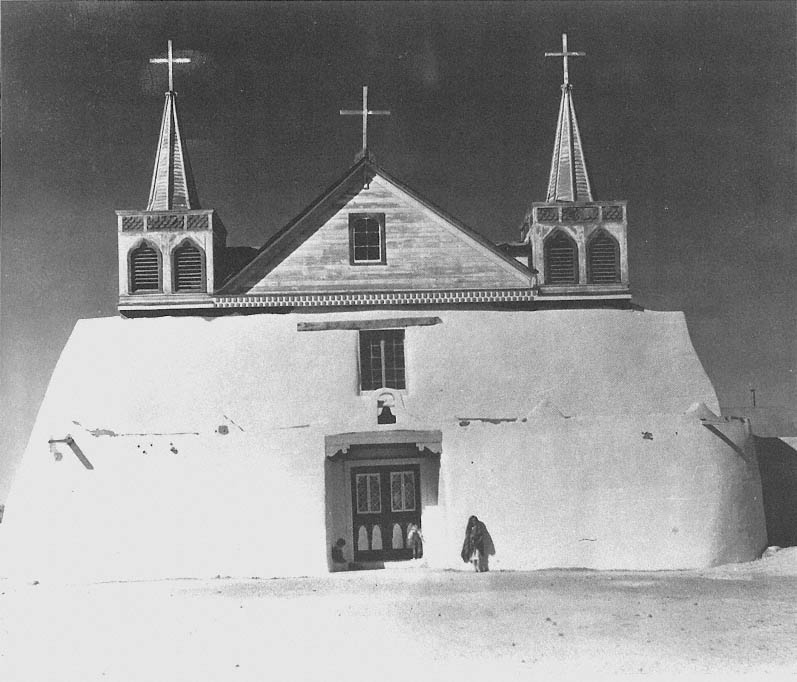

2–5

San Miguel

circa 1881

The apse end of the structure eroded, its mud plaster covering all but

gone, the church's adobes are clearly visible.

Note also the crenellated top courses.

[Museum of New Mexico]

rear wall of the apse currently covered by the reredos. Because no Indian names appeared on the register of workers, there might have been two periods of repair: the first a more cursory effort following Vargas's instructions to get the church back in shape for consecration and the second, carried out in 1710, to glorify its body and raise its aesthetic level. By the end of 1710 the work was finished and a new roof was in place.

The carved beam of the choir loft, which was completely remade at the time, read, "The Marquis de la Peñuela erected this building, The Royal Ensign [sic ] Don Agustín Flores Vergara, his servant. The year 1710."[10] The credit for construction is usually assigned to Vergara, however, Peñuela's name being required by courtesy because he was governor at the time.

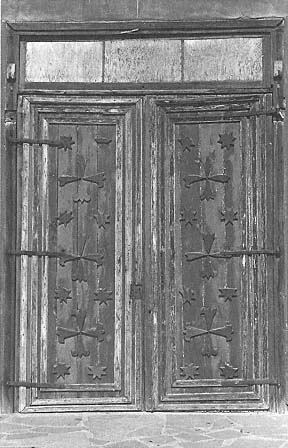

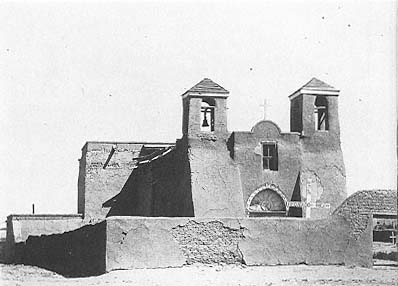

Except for the modified form of the apse, the church was probably built on the same foundations and to the same layout as before. What it looked like, however, remains problematic. A work report noted a carpenter's being paid for four small doors "para las torres" (for the towers), although what the towers referred to remains a mystery. Perhaps the plural "towers" could refer to the tapering stepped tower seen in late-nineteenth-century photographs. But in 1776 Domínguez made no reference to such towers. He may have inadvertently omitted mentioning them, and there is some question as to the accuracy of his report, which placed the sacristy on the north side of the church when archaeological evidence shows that it should have been to the south with the remainder of the convento. A tower scheme might have evolved by the mid-eighteenth century, although this, too, is conjectural. Tamarón, in 1760, was more impressed by the spaciousness of the "principal church" and the promise of the "very fine church dedicated to the Most Holy Mother of Light being built." San Miguel received his visit, if not his enthusiasm; "It is fairly decent; at that time they were repairing the roof."[11]

Domínguez also noted that there were only three windows in the chapel, two in the south wall and one in the west lighting the choir loft.[12] Juan Agustín de Morfi observed that the "section of Analco" was in part regular and that most of it was "without order." He mentioned San Miguel only as "a little church . . . where mass is said to them [genízaros] living in the district on feast days."[13] Bishop Juan Bautista de Guevara's 1818 inventory noted a "little adobe tower without bells," hardly the massive construction that accompanies the crenellations visible in photographs from the 1870s. These may date from an 1830 rebuilding under the sponsorship

of Don Simón Delgado or from a slightly later period.[14]

By the time of the American occupation some century and a half after the refounding of the chapel, the nature of the barrio had changed significantly. Some of the Indian residents had followed the Spanish south during the revolt, others had just left, and perhaps others had stayed to merge with the pueblos. Through intermarriage and resettlement, the composition of the district changed, as did the demands placed on the structure. By the mid-nineteenth century only two formal masses each year were being conducted in the church: on St. Michael's Day, May 8, and on September 29.

With annexation to the United States came increased pressure for universal education to the new Anglo way of life, and with Bishop Lamy's prompting, the Brothers of Christian Schools founded Saint Michael's School on the land just south of the chapel. The brothers bought the church from the diocese on July 31, 1881, and used it as a school chapel, holding services on a daily basis. "In this church," wrote Bourke in 1881, "are paintings hundreds of years old, black with the dust and decay of time, which were brought from Spain by the early missionaries." He recorded the beam carving that credited the builder of the church, but he could not make out its date. "With a feeling of awe we left a chapel whose walls had re-echoed the prayers of men who perhaps had looked into the faces of Cortés and Montezuma or listened to the gentle teachings of Las Casas."[15]

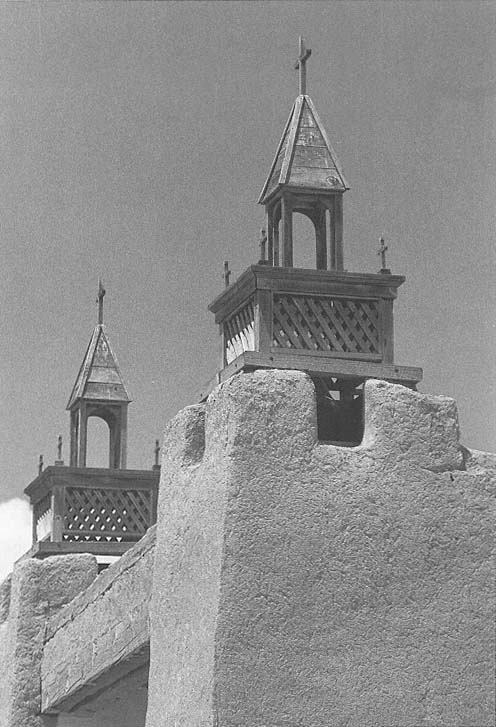

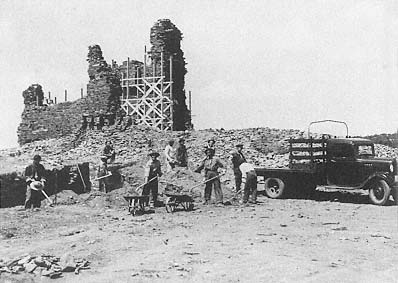

The chapel suffered additional physical vicissitudes, this time as the result of natural forces. The roof had been a perennial problem and had been replaced or repaired in 1730 and 1760. The fourtiered tower was toppled by either a wind storm, as some say, or the undermining of the lower walls. In 1887 the lower part of the tower, which formed a narthex to the chapel, was stabilized and capped with a neat pitched metal roof. The round arches of the bell loft had a decidedly non–New Mexican flavor, and in general the result of the 1887–1888 reconstruction was to anglicize the entrance to the church. At this time a disparity already existed between the architectural characters of the front and rear portions of the building. To reinforce the lower walls of the tower for structural purposes, stone buttresses flanked the entrance. Three similar buttresses on the north wall presumably date from this same period. In 1955, the time of the last restoration, all the elements of the 1887–1888 rebuilding were maintained intact except the stone buttresses on the west facade, which were thickened

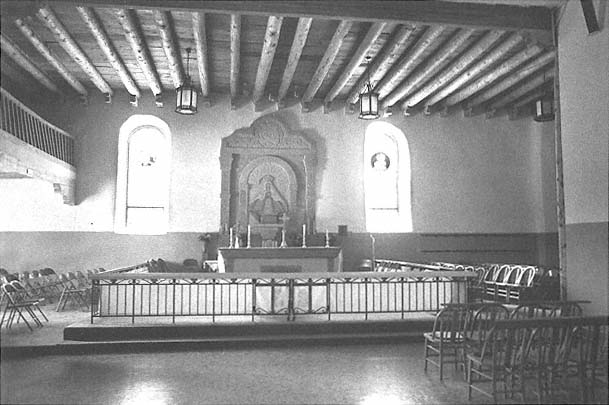

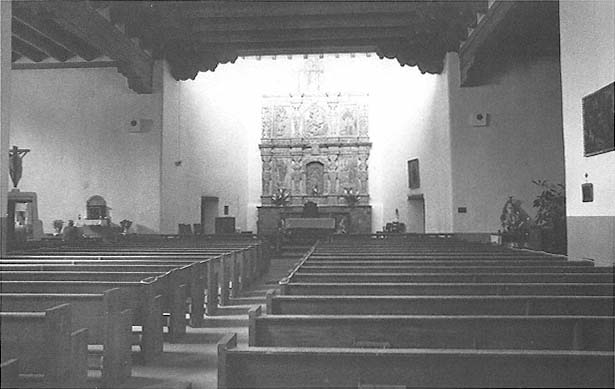

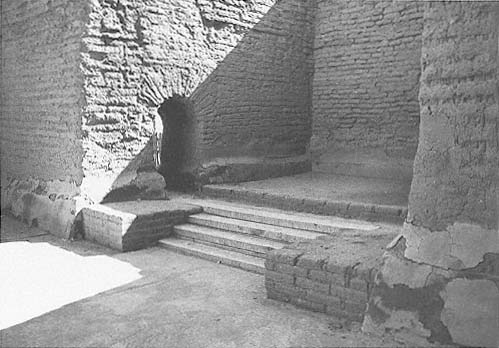

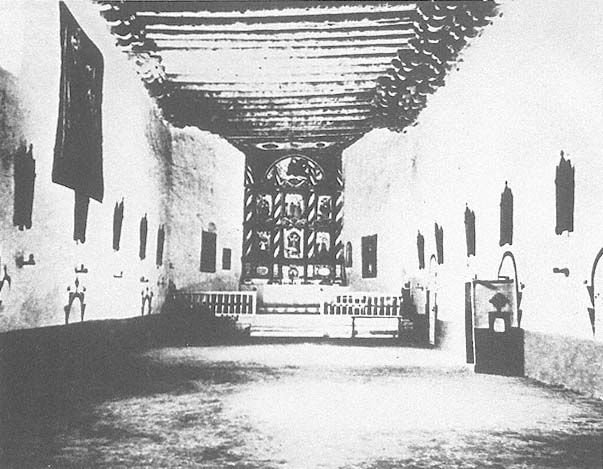

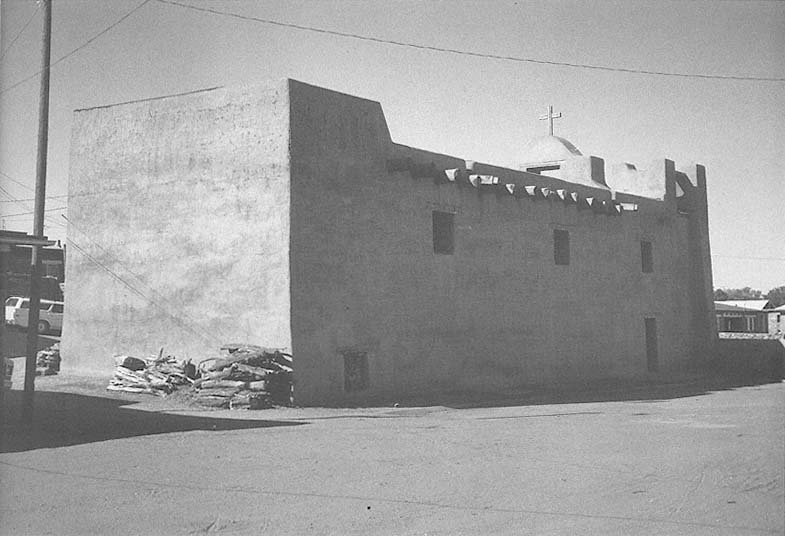

2–6

San Miguel

The church seen from its eastern, apse end.

[1981]

and plastered to bond them visually with the front of the church. The pitched roof was removed, and the Victorian wooden louvers, still in place for the 1934 HABS drawings, were eliminated to create a simpler void in the belfry. The improvements were considerable. In 1978 church authorities requested the Santa Fe architectural firm of Johnson-Nestor to prepare a "Historic Structure Report and Master Plan" to include a comprehensive history of the chapel as well as projected schemes for restoration and maintenance.[16]

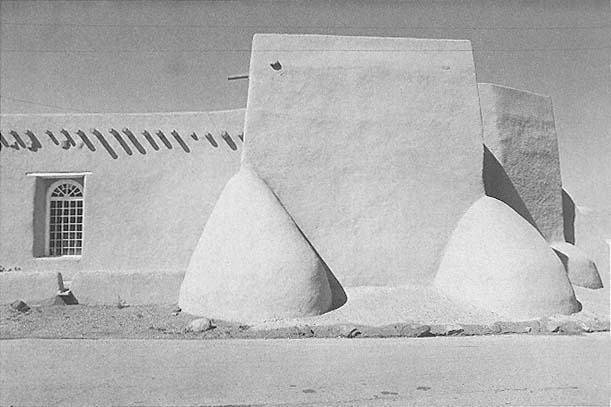

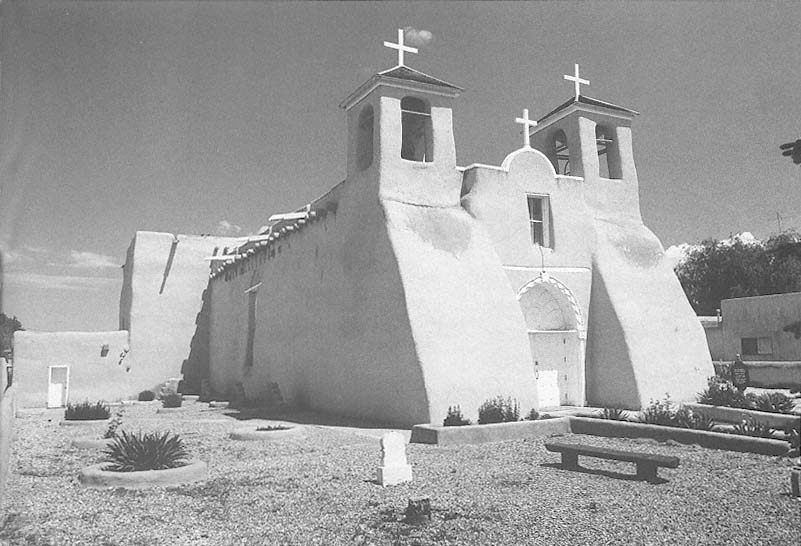

What is the church like today? From the exterior the chapel of San Miguel still appears somewhat uneasy to any eye that has visited several of the mission churches. Its single tower is unlike any others, and the large void in the belfry displays rather awkward proportions for mud-bearing walls. The flanking buttresses appear too thin for adobe construction, and indeed they are made of stone, although stuccoed to conceal that fact. A comparison to those of San Francisco at Ranchos de Taos makes clear the difference in construction materials. And yet in its clumsiness the church does display considerable charm, particularly in its setting in the Barrio Analco, now a historical district that claims the "Oldest House in the United States" just across the street.[17]

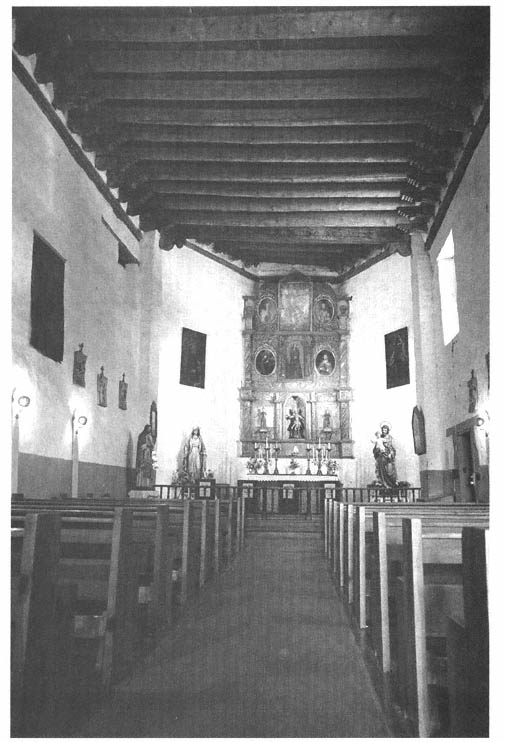

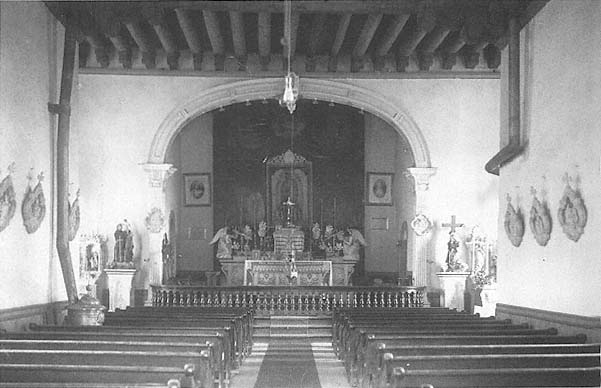

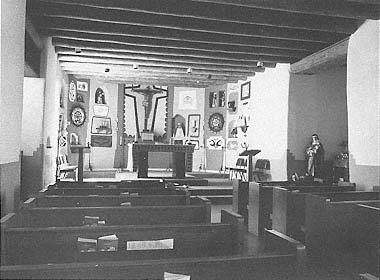

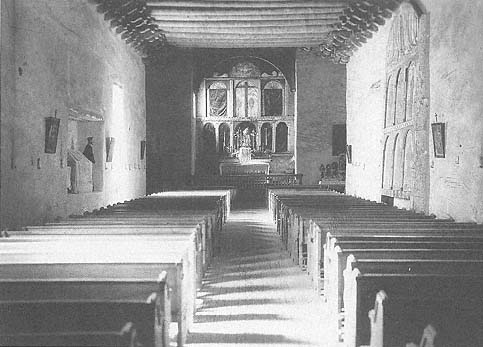

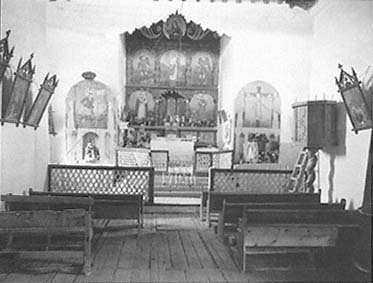

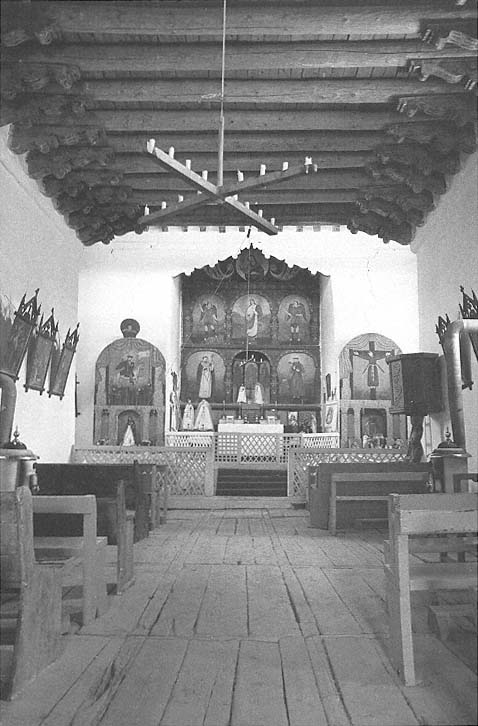

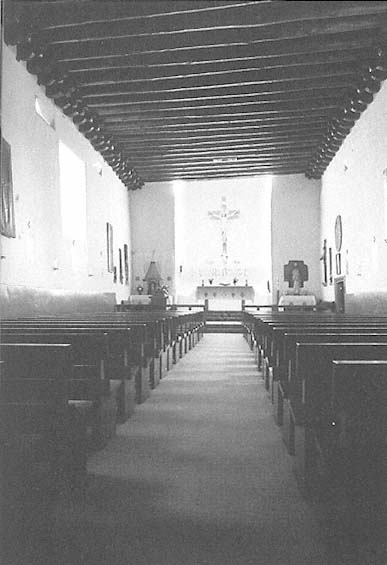

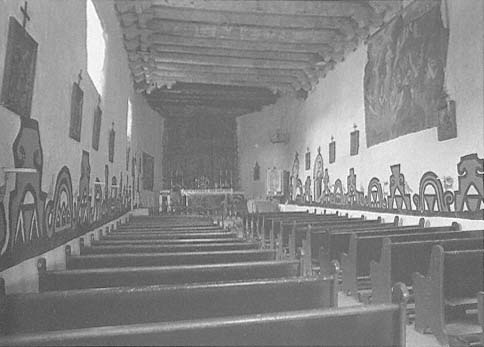

If the exterior is awkward, the church interior appears all the more elegant in comparison. The nave is well proportioned and virtually serene, and with the exception of disturbing recorded messages that play almost incessantly, this is an excellent space in which to consider the history of Spanish architecture in New Mexico. The chapel's shape is classic, with its single nave roughly twenty-four feet wide and seventy feet long and tapering decisively toward the east. The years upon years of replastering have added to the mass of the walls, whose textures indicate the accumulation of time like the steady movement of a clock. In the afternoon when the sun is right, the light sliding through the clerestory is quite striking, evoking a sense of the beauty and drama of light and its role in creating religious presence. With the north windows blocked and the south windows high in their wall, only artificial light detracts from the total effect.

The majority of the vigas, in fact all but two, date from rebuildings in the nineteenth century, and only the two square ceiling beams in the chancel survive from earlier times. The balcony support beams and all the corbels are beautifully carved and lend an air of elegance and polish to the simple interiors. In the course of subsequent renovations, including the work of 1798, the floor was raised two feet with adobe; thus the distinction between the sanctuary and the nave was lessened. In 1853 Bishop Lamy built a stone altar, followed in 1862 by a new communion railing. The wooden floor dates from 1927, and the pews, the most recent addition, were not installed until 1950.

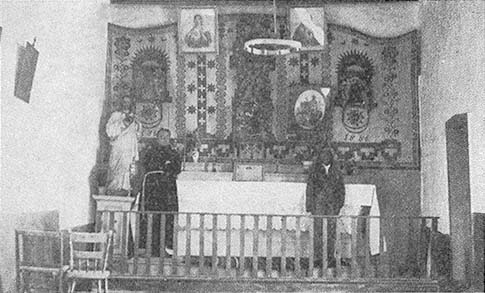

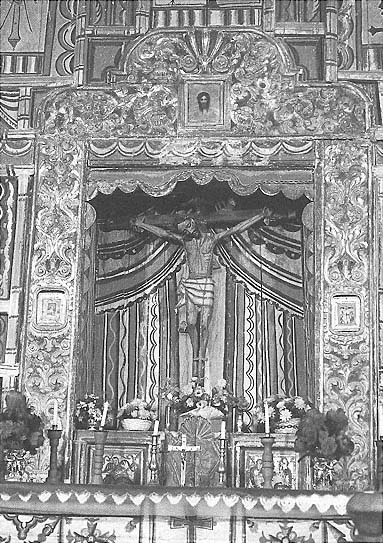

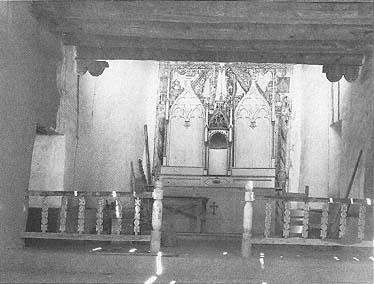

The full-height reredos, which fills the front of the sanctuary, is said to be the oldest in New Mexico. In the center is the small figure of Saint Michael the Archangel. In one hand he holds a sword drawn to conquer Satan; his jeweled crown symbolizes victory. Dating from 1709 and brought from Mexico, the reredos has resided at San Miguel since at least 1776, as evidenced by its inclusion in Domínguez's inventory.

The chapel of San Miguel has had its judgments and suffered its destructions and rebirths. Now protected by law and operated by the Christian Brothers, it is more secure than it has ever been in three hundred–odd years of existence.

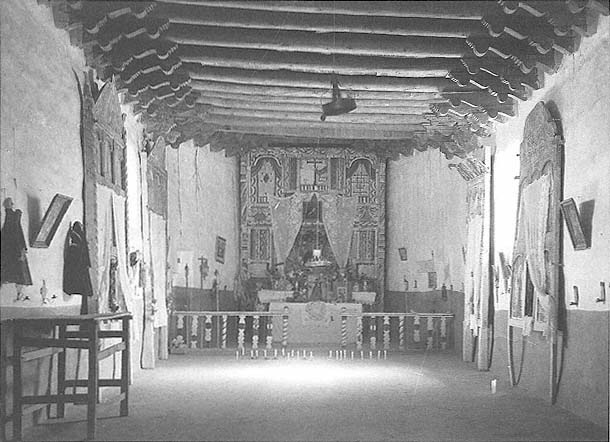

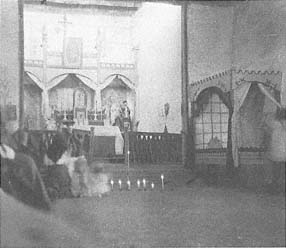

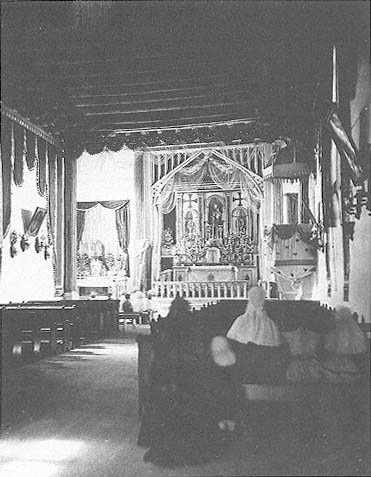

2–7

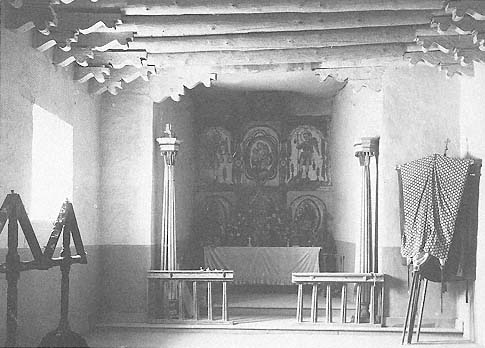

San Miguel

The church interior in the late nineteenth century. Compare the state of the reredos

with its contemporary condition.

[Museum of New Mexico]

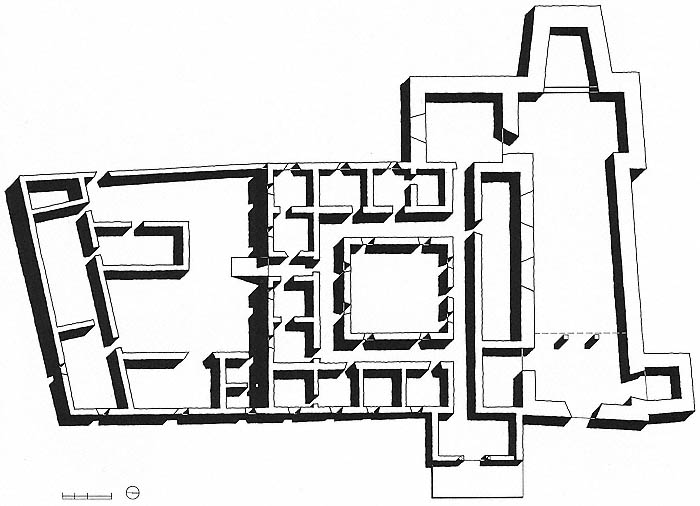

2–8

San Miguel, Plan

[Source: Kubler, The Religious Architecture , 1940; and field

observations, 1986]

2–9

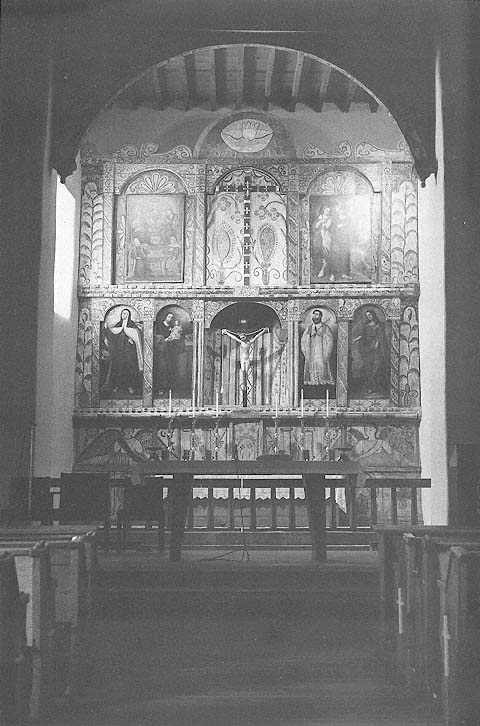

San Miguel

The reredos with the figure of San Miguel occupying the central niche.

[1981]

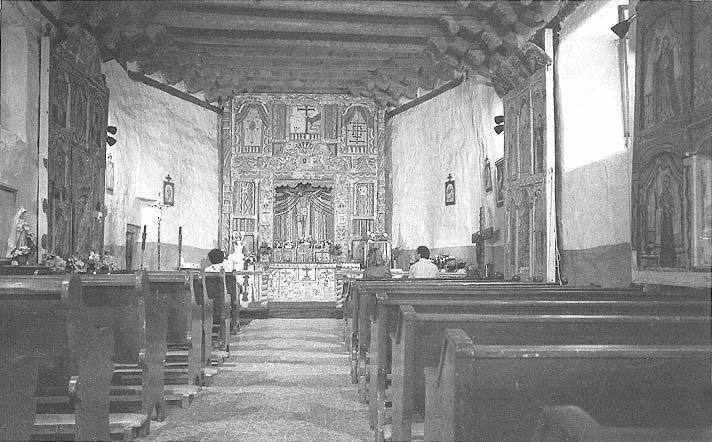

2–10

San Miguel

With its narrow section, heavy vigas, and battered chancel, the nave is a classic representative

of New Mexican colonial religious architecture.

[1981]

La Parroquia

1610?; 1626–1639; 1713–17; 1796–1806

The Cathedral of Saint Francis

1869–1895; 1966; 1986

Architects: Antoine and Projectus Molny; François Mallet

When the location of the provincial capital at San Gabriel proved to be impractical, it was moved south to Santa Fe, where it has remained since its establishment in 1610. The city complied only roughly with the ordinances for founding new cities. These regulations dictated that the "principal church" was not to occupy the central position on the plaza mayor, which was reserved for the most important civil structures of authority. The plaza was to be the center of the municipality and would be augmented by "smaller plazas of good proportion . . . where the temples associated with the principal church, the parish churches, and the monasteries can be built." More specifically, "the temple [principal church] shall not be placed on the square but at a distance and shall be separated from any other nearby buildings, or from adjoining buildings, and ought to be seen from all sides so that it can be decorated better, thus acquiring more authority."[1] "Decoration" was a long time coming to the church in Santa Fe, and in spite of the ordinances, the Parroquia was tucked on the southeast corner of the plaza.

Like the city itself, the church—today the cathedral—still occupies the same site, although the location of the church itself has shifted slightly over the years. The identification of the original structures is made more difficult by the construction of commercial structures in the nineteenth century, which eradicated the entire eastern half of the plaza. The Parroquia as such no longer exists: the building was subsumed by the stone cathedral, substantially completed in the 1880s, that succeeded it.[2]

The parish church was not the first major religious structure in the capital. That honor fell to the chapel of San Miguel across the Santa Fe River in the Barrio Analco (see San Miguel). An appropriate parish church was a necessity, however.

According to Kubler, a rudimentary chapel existed on the site of the Parroquia as early as 1610 and was probably the product of Fray Alonso de Peinado's first efforts.[3] It possessed neither commodity nor architectural quality and was later referred to by Benavides as a mere plastered pole structure (jacal).[4] Appreciated or not, this original church was dedicated to Nuestra Señora de la Asunción (Our Lady of the Assumption).

By 1626, when Benavides took office, or by 1630, when his first report was published, about two hundred fifty Spaniards lived in the city and roughly three times that many Indians were affiliated with them, most of them serving in menial positions. The town was lacking a suitable parish church, Benavides related, "as their first one had col-

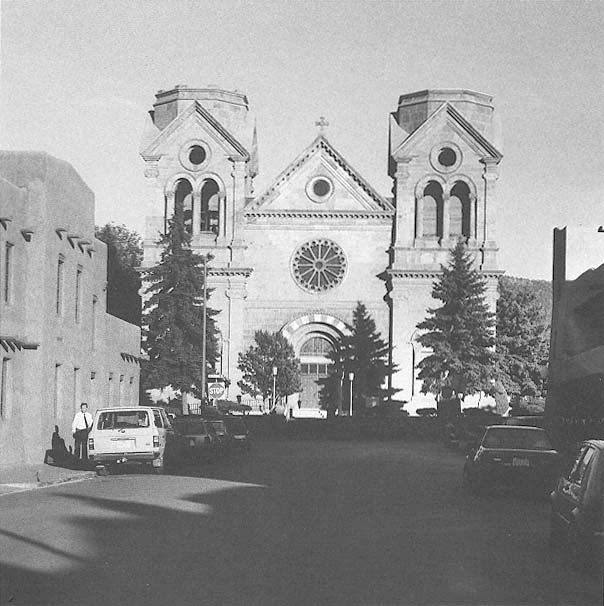

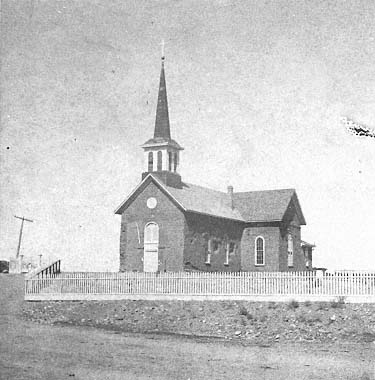

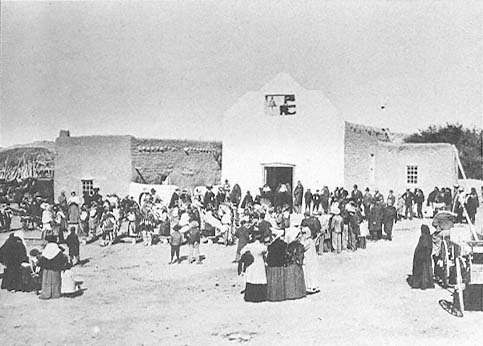

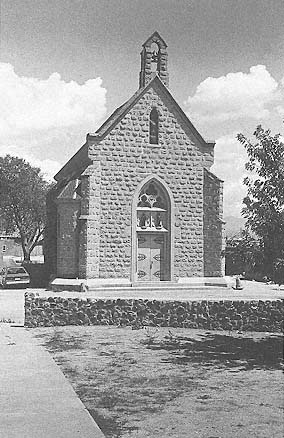

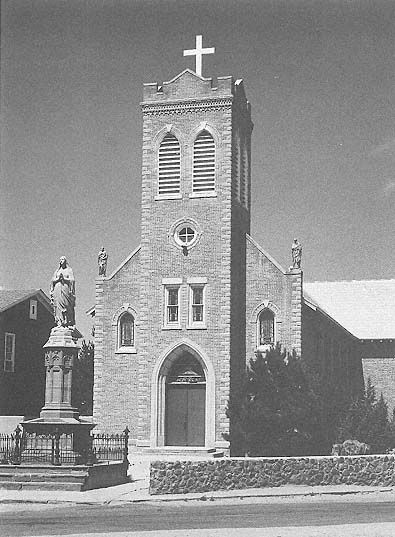

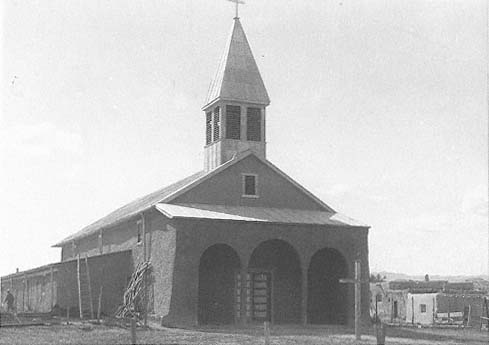

3–1

Cathedral of Saint Francis

The spireless principal (south) facade, based on a design by Antoine and Projectus Molny, executed in a style

recalling the Romanesque religious structures of their native France.

[1986]

lapsed. . . . I built a very fine church for them, at which they, their wives and children, personally aided me considerably by carrying the materials and helping to build the walls with their own hands, to the honor and glory of God," and not incidentally to the glory of the friar himself.[5] The institution seemed to progress satisfactorily: "We have them well instructed, and they set a good example. The most important Spanish women pride themselves on coming to sweep the church and wash the altar linen, caring for it with great neatness, cleanliness, and devotion, and very often they come to partake of the holy sacraments."[6]

While the second parroquia was under construction, San Miguel served as the parish church. Chavez believed that construction of the convento might have preceded or progressed more rapidly than the church itself because the convento was probably in use by 1631. Construction of the church was completed by 1639. The dedication of the church possibly changed, as in 1661 there were references to a church of the immaculate conception.[7] Fronting the church and extending westward toward the plaza was the cemetery. The convento lay south of the nave, which was oriented east-west. A report from the 1640s recorded that the capital of the territory was also the seat of the custodia and that it had "a very good church in which is kept the Blessed Sacrament; everything pertaining to public worship is very complete and well arranged; it has a fair convento, and there are 200 Indians under its administration who are capable of receiving the sacraments."[8]

Unlike nearby San Miguel, the Parroquia was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt, and although Vargas vowed to rebuild the ruined structure in 1693, he in fact never did. What remained of the pre-1680 structure was rebuilt as the existing Conquistadora chapel and was refurbished to house the statue of the Virgin that had accompanied the Vargas expedition of Reconquest (see El Rosario). The population of the city had grown, increasing pressure for the erection of a religious edifice of more appropriate stature. The convento for the Franciscans, however, had been maintained through the auspices of Governor Cubero, who took office in 1697. Within fifty days of his arrival, repair work was "for the most part" completed.[9]

A chapel in the east torreón of the Palace of the Governors still stood at the time of the Vargas entry into Santa Fe. During the years of native occupation the chapel had been converted to serve as a kiva. Necessity seems to have triumphed over desecration, as the chapel was reconsecrated and served as a center of worship until the construction of the

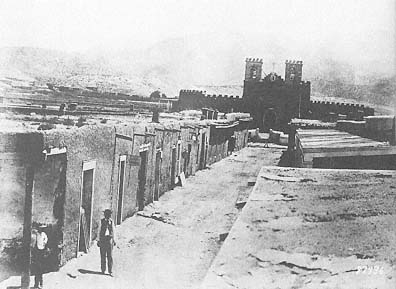

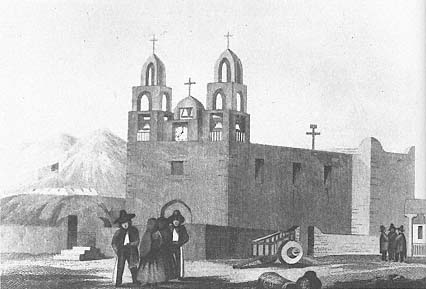

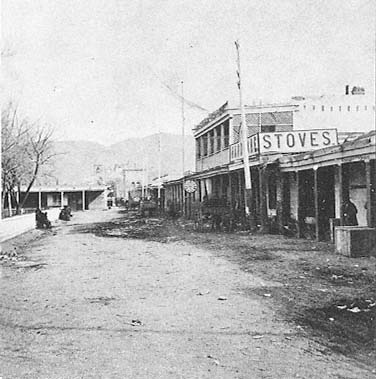

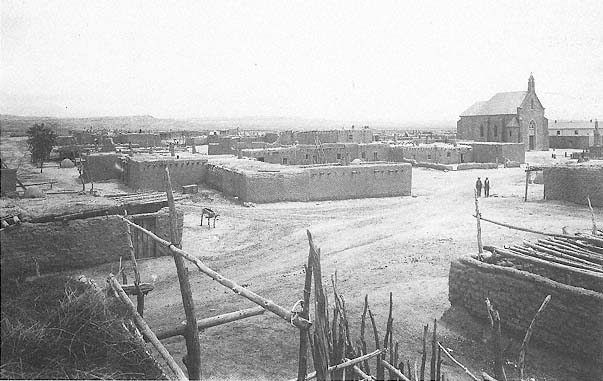

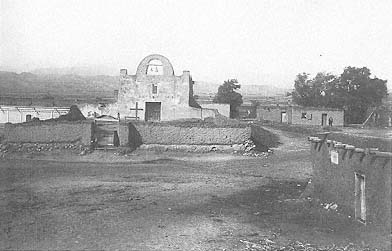

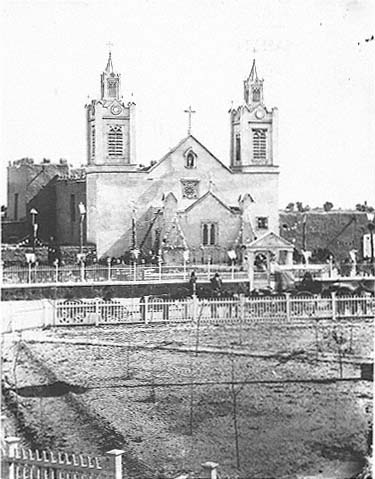

3–2

Looking North on San Francisco Street

Circa 1878

The Parroquia stands at the end of the street.

[U.S. Signal Corps, Museum of New Mexico]

new parroquia almost two decades later.[10]

The new church, shifted on its original site, was under construction in 1713, as evidenced by two documents referring to building activity. One, dated 1713, referred to "the church which is now being built in Santa Fe"; the second described a house "on the main street which goes from the Plaza to the new church now being built."[11] The structure was probably completed by 1717, and from then until the end of the eighteenth century, the building suffered continual decay. Tamarón noted its existence in his report of 1760 but had little to say either in praise or condemnation: "On May 25 [1760], which was Whitsunday, the visitation was made with all possible solemnity in the principal church, which serves as the parish church. It is large, with a spacious nave and a transept adorned by altar and altarscreens."[12] Tamarón appeared more caught up with the excitement of building the chapel of Nuestra Señora de la Luz (Our Lady of the Light) on the south side of the plaza.

"Surely when one hears or reads Villa of Santa Fe, along with the particulars that it is the capital of the kingdom, the seat of political and military government with a royal presidio, and other details that have come before one's eyes in the perusal of the foregoing," wrote Domínguez in 1776, "such a vivid and forceful notion or idea must be suggested in the imagination that reasons will seize upon it to form judgments and opinions that it must at least be fairly presentable, if not good." Alas, the city did not live up to those expectations. In all, he had little that was positive to say about the villa other than to remark its splendid site: "Its appearance, design, arrangement, and plan do not correspond to its status as a villa nor to the very beautiful plain on which it lies, for it is like a rough stone set in fine metal."[13]

The Parroquia, in his estimation, fared a little better. He noted that it was built of adobe, that its doors faced west, and that its "regular transept" was raised three steps up from the rest of the nave. He gave no hint that the walls of the church converged slightly toward the transept. "Across the mouth of the nave a clerestory rises to light the transept and the sanctuary," while three windows in the south wall lit the nave. "The church has a choir loft in the usual place which occupies the full width and projects 5 varas into the nave. . . . The entrance is below it near a corner, like a trap door, reached by a ladder inside the church. Its furniture, or adornment, is the entire absence of any, for there is not even a bench for the singers. The floor is bare earth packed down like mud."[14] The effort of making the building registered favorably on the visitor, perhaps more than the actual structure. He conscientiously recorded what was there: the cemetery, the floor of wooden planks, the governor's throne in the transept, and the wooden altar screen. In addition to the two altars in the chancel, four more flanked the nave, two on either side. The beams in the ceiling were new, suggesting a recent renovation. The baptistry stood to the right, adjacent to the convento to the south, and was entered under the choir. Protecting the image of the Conquistadora, the Rosario chapel extended the north transept and was built in the typical manner, although it lacked a clerestory. Domínguez's judgment was mild: "Its interior may not be cheerful, but it is not gloomy either."[15] Whereas the Benavides church may have borne only a plain facade, the eighteenth-century church featured two tower buttresses spanned by a balcony from which "all the view the villa has to offer to the north, south, and west can be easily surveyed."[16]

Before 1797 portions of the church had dangerously deteriorated and had subsequently been rebuilt. The inevitable processes of entropy and erosion were only temporarily halted, however, as the church was again in ruinous condition or had even collapsed by 1799.

In 1804, by which time the walls had been substantially completed, disaster called: just before the roof beams were scheduled to be installed, the church was struck by lightning and the new construction was destroyed. The sponsorship of the rebuilding is credited to Don Antonio José Ortiz, who also funded improvements to San Miguel about the same time.

After it [the parish church in this city] had fallen down, six years ago, I undertook by myself to reconstruct the same, and in fact I [prepared it] for the vigas last year. [O]wing to the damage of lightning which struck, I was obliged to tear it down again and enlarge it ten varas. From the foundation up I extended it 8 varas and reconstructed its walls and have it now ready nearly up to the placing of the vigas, there missing four rows of adobes in order to be able to roof it.[17]

Ortiz paid to lengthen the church toward the west and to erect a chapel dedicated to San José that extended the south transept. The church thus filled out a cross-shaped plan configuration, while the Conquistadora chapel and chancel were recast into the characteristic battered form.[18] Renewed efforts completed the structure in 1808.

The church form at that time displayed certain properties still observable in the earliest photographs of the Parroquia since it was described in a report by Agustín Fernández, vicar general of the

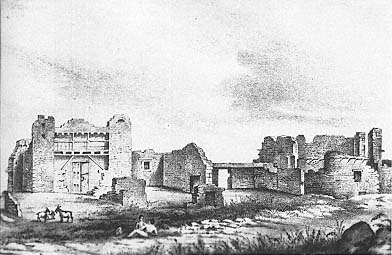

3–3

La Parroquia

The church in 1846 as sketched by J. W. Abert.

[Museum of New Mexico]

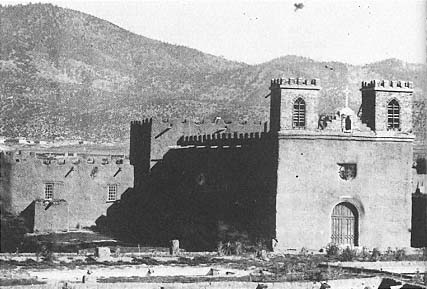

3–4

La Parroquia

circa 1867

Within a decade of Lamy's arrival in New Mexico, the Parroquia was polished with

a mild Gothic trim.

[Nicholas Brown, Museum of New Mexico]

archdiocese of Durango, as having two small towers and measuring about 29 feet by 162 feet—a relatively long and narrow space.[19] The elongation of the nave in subsequent rebuildings reduced the dimensions of the campo santo, thereby bringing the facade closer to the plaza.

When the Americans entered the city in 1846, they found the church, made of adobe, little changed in architectural style from the previous century. Typically, the mass of the church and the manner of the pious stood foremost in the eyes of observer Lieutenant J. W. Abert.

October 4, 1846. We were early awakened with the ringing of the campanetas, summoning the good citizens of Santa Fe to morning mass at the parroquia, or parish church. I had a great desire to see the interior of this church, which with the "Capilla de los Soldados," are said to be the two oldest churches in the place, and were doubtless those alluded to by Pike, when he says, "there are two churches, the magnificence of whose steeples form a striking contrast to the miserable appearance of the houses." . . . The body of the building is long and narrow; the roof lofty; the ground plan of the form of a cross. Near the altar were two wax [wooden] figures the size of life, representing hooded friars, with shaved heads, except a crown of short hair that encircled the head like a wreath. One was dressed in blue and the other in white; their garments long and flowing, with knotted girdles around the waist. The wall back of the altar was covered with innumerable mirrors, oil paintings, and bright colored tapestry. From a high window a flood of crimson light, tinged by the curtain it passed through, poured down upon the altar. The incense smoke curled about in the rays, and, in graceful curves ascending, lent much beauty to the group around the priests, who were all habited in rich garments. There were many wax tapers burning, and wild music, from unseen musicians, fell pleasantly upon the ear, and was frequently mingled with the sound of the tinkling bell. . . .

In the evening [of October 5] I made a sketch of the parroquia, although mud walls are not generally remarkable; still, the great size of the building, compared with those around, produces an imposing effect.[20]

Like Abert, Lieutenant William Hemsley Emory was taken by the activity more than the space:

August 30. This was on a Sunday.

Today we went to church in great state. The governor's seat, a large, well-stuffed chair, covered with crimson, was occupied by the commanding officer. The church was crowded with an attentive audience of men and women, but not a word was uttered from the pulpit by the priest, who kept his back to the congregation the whole time, repeating prayers and

3–5

La Parroquia

1880

In this illustration by Charles Graham, probably based on a

photograph by Ben Wittick, a wooden arch distinguishes the

central nave from the sanctuary.

[Museum of New Mexico]

3–6

Cathedral of Saint Francis

1880

Taking advantage of some clever planning strategy on the part of the

architects, the builders used the roof of the Parroquia as a work platform

for the new stone structure rising around it.

[Museum of New Mexico]

incantations. The band, the identical one used at the fandango, and strumming the same tunes, played without intermission. Except the governor's seat and one row of benches, there were no seats in the church.

The interior of the church was decorated with some fifty crosses, a great number of the most miserable paintings and wax figures, and looking glasses trimmed with pieces of tinsel.[21]

Five years later when Jean-Baptiste Lamy arrived in New Mexico, he set to putting his house in order. Although he might have harbored no love of the native architecture, aesthetics was not the major issue. "The trouble with the native tradition as Bishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy and his French priests saw it was that New Mexican Catholicism of the times too closely resembled its crumbling churches," wrote Bruce Ellis in a recent monograph on the cathedral.[22] As a cathedral, rather than a parish church, the building demanded a greater expression: "No adobe-walled, viga-spanned structure could be as high or as wide as proper cathedral dignity required; to permit its consecration in strict accordance with canon law the building must be of solid masonry throughout."[23] Yet another factor was the chronic repair demanded by adobe construction: why not build a masonry structure that required less maintenance? Nor was there popular support for the existing structure on the basis of its historical significance—such appreciation would have to wait another century to flourish. For the moment modernity and progress held sway over sentiment. "When finished," a newspaper editor wrote in 1873, "the edifice will be a credit and an ornament to the city and territory. . . . That old mud church [the Parroquia] has stood for years looming up dingy, gloomy, and awkward, like an adobe brick-kiln—an eyesore to every man of taste and a disgrace to the city."[24]

After saving and repairing the Castrense chapel, Lamy sold it in 1859 to raise money for the Parroquia and to acquire a piece of land upon which to erect a school. But he also had bigger plans in mind, and they had little to do with traditional Spanish colonial building types. The parroquia had become his cathedral, and the bishop sought a church building that would objectify the church's newly elevated status. Neither adobe nor local builders could produce what he envisioned, and for stylistic expression he looked, not to the land around him or its parent country of Spain, but back to his mother country of France.

Lamy's search had numerous precedents in the history of ecclesiastical architecture. Early in the

1840s Greek and Roman revivals had been used to reinvigorate the spirit of the American republic, however farfetched and muddled the stylistic associations were. Among the Catholic and Episcopal faiths Gothicism became the predominant religious architectural style, mostly through the original instigation of A. W. N. Pugin, who looked back to the medieval era in Europe as the most fervent—and truest—expression of Christian religion. The impact of medievalism was felt as far afield as New Mexico, where many of the simple adobe churches received at least minor Gothic redressing. Early photos of the Parroquia show that it, too, was modified under this influence, with crenellations added to the parapets and pointed arches to the belfries.

It was not the Gothic style, but the Romanesque, in which the cathedral of Santa Fe was finally built. Lamy came from southern France, where the Romanesque churches of the eleventh and twelfth centuries remained the major monuments—the Gothic cathedrals were mostly built farther north in the Isle-de-France or further east. In spite of years of living and working abroad, even in the relative wilderness of Kentucky, Lamy retained his early stylistic preferences. But the Frenchman encountered problems in realizing his vision: lack of a building tradition that used the vault and the arch was one; lack of money was another. The new bishop overcame them both. He imported the architects Antoine and Projectus Molny from France as well as certain craftsmen who worked with local crews. Molny probably prepared his drawings while still in France and sent them to Santa Fe "in or just before 1860."[25]

As in any project of this size, complications arose. At the start the work was given to an American contractor who either was "dishonest" or "did not understand the work."[26] In 1869 work commenced; the cornerstone was laid on October 10—and stolen within a week! "Some heathen with infamous hands tore up the cornerstone of the new cathedral which had been laid by Bishop Lamy only the Sabbath preceding . . . and everything of any value, silver and gold coins, etc., etc., were [sic ] carried off."[27]

The strategy for erecting the new cathedral was rather ingenious. Because the Parroquia would be in use during the period of construction, the new structure would be built over and around it. The width of the existing church would determine the width of the central nave, which would be flanked on either side by an aisle. The roof of the Parroquia would serve as a useful platform for the construction of the vaults of the masonry structure.

A red native stone was chosen for the walls and a

3–7

Cathedral of Saint Francis

An engraving of the revisions proposed by Francois

Mallet to the Molny scheme, including completion of

the spires left as stubs.

[From Aztlan , by William G. Ritch, 1885; Museum of

New Mexico]

3–8

Cathedral of Saint Francis, Plan

[Sources: Architects' drawings by McHugh Loyd Associates; and field observations,

1990]

volcanic tufa for the ceiling, which established a prototype for succeeding religious architecture in New Mexico—although few, if any, builders followed it. Modifications were made en route: the width of the proposed facade was reduced and rotated slightly to align it with the streets. Work stopped for about four years beginning in 1874, and a new architect, François Mallet—French, living in San Francisco—replaced Antoine Molny, who had returned, blind, to France in 1874. Mallet prepared documents and an estimate for completing construction, including the two spires that were never built.[28] When the centering for the vaults was removed, cracks appeared, prompting the insertion of triple arches between the pillars.[29] The arrival of the railroad facilitated the movement of some materials, although stone was still transported to Santa Fe from Lamy by teams. European workmen arrived in 1883, lending their stone-carving skills to the project.[30] A year later construction had reached a point sufficient to permit the final demise of the adobe Parroquia, its earth used to fill the streets of the city: "Its adobes and rocks are now doing other public work," said Father James Defouri.[31]

In time the cathedral rose, with its new stone walls surrounding the venerable adobe church it was to supersede in majesty and style. John Bourke, writing in 1881, observed the construction process and its results:

I went to the Cathedral of San Francisco, a grand edifice of cut stone, not more than half completed and enclosing within its walls the old church of adobe. As I purpose, at a late date, giving a more detailed account of this old building and others equally venerable in Santa Fe, as well as a sketch of the town itself, I will content myself now with saying that the town has been transformed by the trick of some magic wand during the past 12 years. . . .

The old church in itself is a study of great interest; it is cruciform in shape, with walls of adobe, bent slightly out of the perpendicular. Along these walls, at regular intervals, are arranged rows of candles in tin sconces with tin reflectors. The roof is sustained by bare beams, resting upon quaint corbells. The stuccoing and plaster work of the interior evince a barbaric taste, but have much in them worthy of admiration. The ceilings are blocked out in square panels tinted in green, while two of the walls are laid off in pink and two in light brown. The pictures are, with scarcely an exception, tawdry in execution, loud colors predominating, no doubt with good effect upon the minds of the Indians. The stucco and fresco work back of the main altar includes a number of figures of life size, of saints I could not identify and of Our Lady. In one place, a picture of the Madonna and Child represents them both with gaudy

3–9

Cathedral of Saint Francis

The unusual configuration of arches and columns

reflects revisions made to ensure structural stability.

[1981]

crowns of gold and red velvet. The vestments of Archbishop Lamy and the attendant priests were gorgeous fabrics of golden damask.[32]

By 1886 the church was substantially completed, but a construction hiatus in 1895 left the eastern end of the church in adobe until 1966. Structural and economic problems continued to haunt the structure. During the 1930s cracks again appeared in the vaults and north wall, belying the problematic soil of the old burial ground and the poorly laid foundations. With John Gaw Meem as consultant, the foundations were reinforced in an attempt to stabilize the settlement.[33]

What was left after the removal of the Parroquia was a competent Neo-Romanesque church with two side aisles, round arches, a great rose window, and the stubs of two eighty-five-foot towers that would never receive their spires. At the time it must have appeared as a very impressive structure unlike anything ever seen in the territory. Today it is a handsome church with little of particular aesthetic note. If there is a lesson to the venture, it might be that a provincial version of an international style is often of less interest and emotion than a superb example of a local tradition. Nevertheless, the traditional style was unable to produce a structure of a cathedral's desired scale and magnificence. A recent renovation, executed in 1966–1967, demolished the remaining adobe structures except for the Conquistadora chapel and introduced a south chapel dedicated to the blessed sacrament that also serves daily as the entrance to the cathedral.[34] A grand skylight floods the altar with light. In the mid-1980s renovations designed by McHugh Lloyd and Associates, Santa Fe, were again in progress, flooring the crossing and the sanctuary in a pattern of light and dark wood.

Recent revisions in ecclesiastical doctrine resulting from the Vatican II accord have brought about the modification of many traditional church interiors, and this last renovation is one such project. Liturgy will always determine church architecture; the process is inevitable. Unfortunately, the new lighting lacks the orchestration characteristic of traditional church architecture. The ambient nature of the cathedral's light has reduced the light quality from a source of inspiration or wonder to a source of illumination. The miniature Conquistadora chapel, however, remains the cathedral's north transept and retains the character of its predecessors, a reminder of the humble beginnings of the city and its "principal church."

3–10

Cathedral of Saint Francis

circa 1948

The church during services.

[Robert H. Martin, Museum of New Mexico]

3–11

Cathedral of Saint Francis

The altar area was opened during the renovations begun in 1986. Although the sanctuary is

bathed in light, the unorchestrated quality of the illumination is foreign to the choreographed

play of lighting in the traditional New Mexican church.

[1986]

El Rosario

(1693?); 1808–1818; 1914

Don Diego de Vargas paused, tradition has it, on a hill outside Santa Fe, which today is graced by a shopping center named in his honor, and declared that if he were successful in retaking the city, he would erect a chapel on the site as a token of his gratitude. His prayer seems to have been answered, although not immediately. His attack was repelled. He prayed again to the Virgin and set out: this second time he was successful.

On their journey north from El Paso, the Spanish were accompanied by a small Mexican wooden image of the Virgin, with which they had fled in 1680. The image had originally been brought to New Mexico by Benavides in 1625 and was taken south on the retreat from the Pueblo Rebellion in 1680. The Reconquest was enacted in her name—hence the title "La Conquistadora"—and the statue is currently housed in the north chapel of that name in the Cathedral of Saint Francis.[1] There is an alternate legend as well: that the statue became so heavy when carried past that spot that it was regarded as an omen for the construction of a chapel.

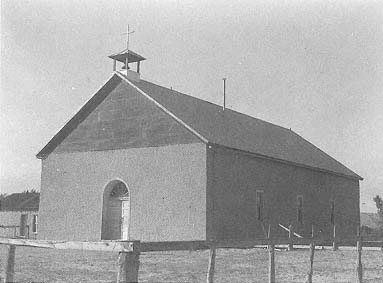

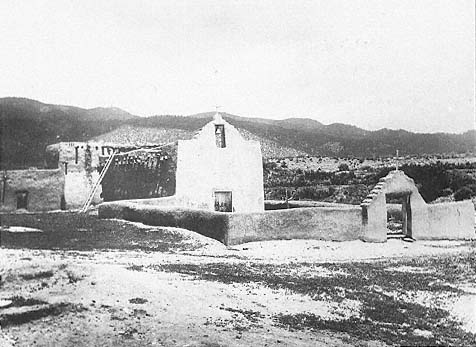

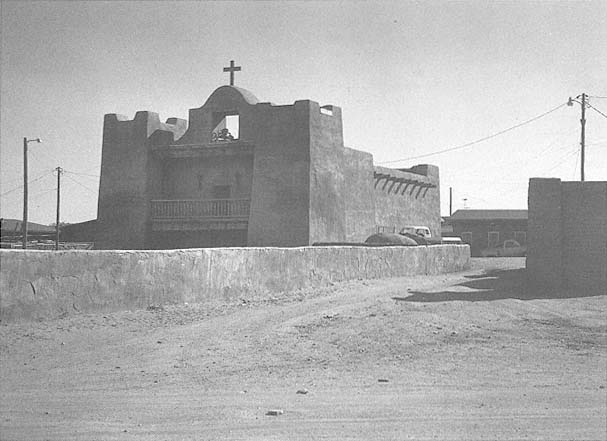

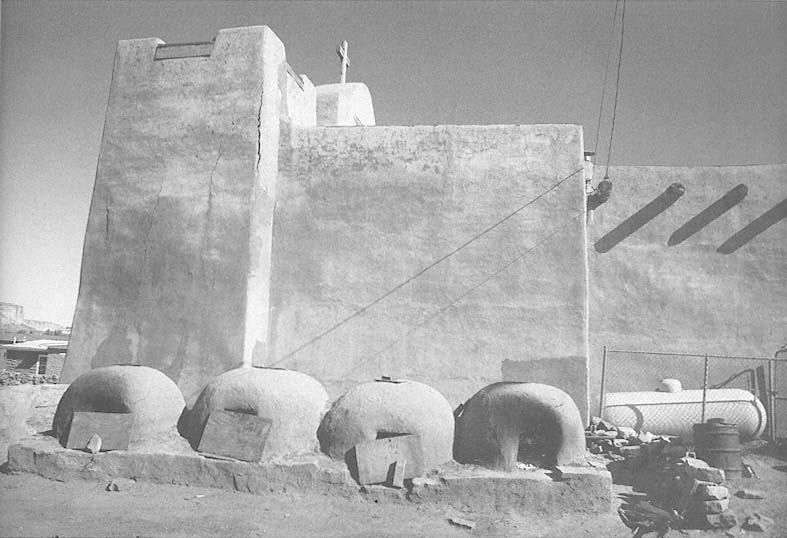

A small wayfarer's chapel might have been erected on the site, although the exact date of construction is unknown, as is whether it was actually built under Vargas's instigation. There is, in fact, no documented evidence that the tale is true since the usual sources, such as Tamarón and Domínguez, made no mention of the chapel. If there had been an earlier structure, it was so deteriorated by the turn of the nineteenth century that a new one was built between 1808 and 1818, most probably 1806–1807 because the license was issued in 1806. The Ortiz family, which had underwritten repairs at San Miguel and the Parroquia, commissioned Pedro Fresquís to paint the altarpiece and supported construction of the chapel as well. The reredos served primarily as a frame for the statue of the Conquistadora and was executed in the characteristic, somewhat scrappy and rough style of Fresquís.[2] The chapel fits the typical New Mexican pattern, with a single nave, battered apse, flat roof with clerestory, and choir loft at the south-facing entry. The land has become a national cemetery, and about 1915 an addition that greatly diminished the presence of the older chapel was constructed. The new wing, which now makes up two-thirds of the current structure, lacks particular architectural distinction. It is more a neutral building turned perpendicularly to the axis of the original church. Thus serving as the chancel and transepts to the current structure, the historic chapel with its altar and reredos has been reduced to a subsidiary role.

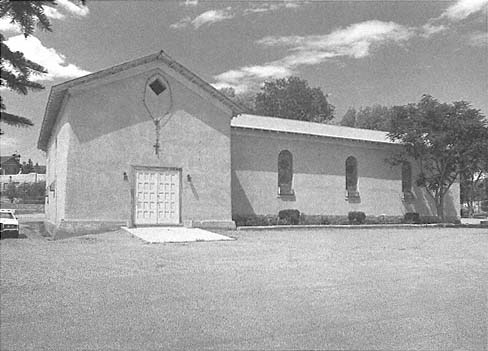

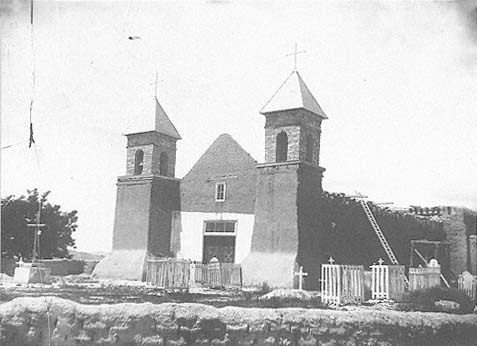

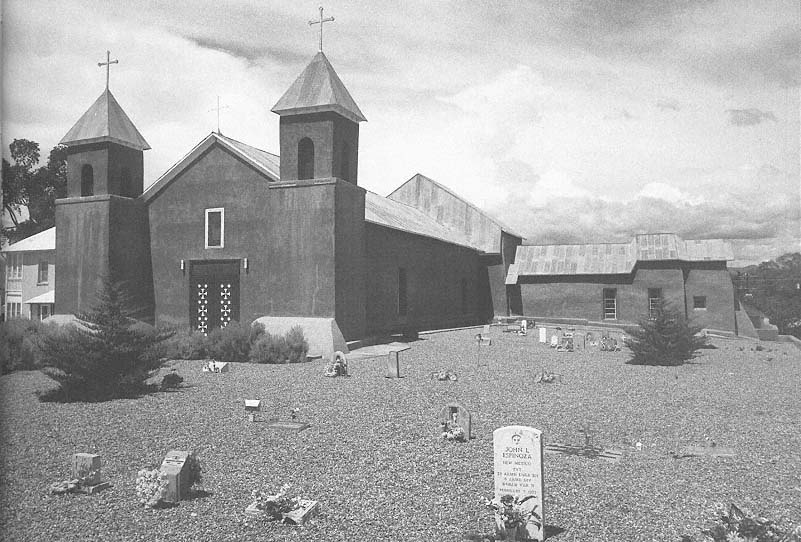

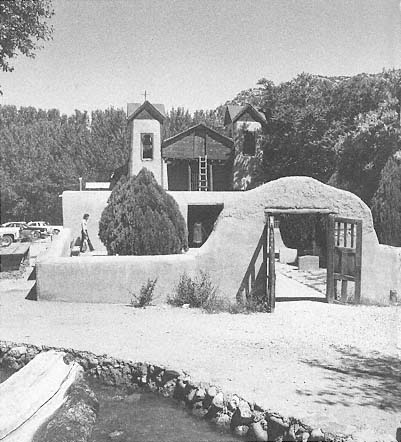

4–1

El Rosario Chapel

The twentieth-century expansion reconfigured the original chapel as the transepts and

sanctuary of the new structure.

[1986]

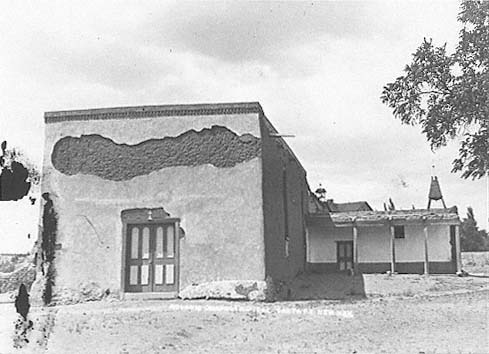

4–2

El Rosario Chapel

1911

In spite of the rows of fired brick used both to stabilize the parapet and add a touch of

Territorial ornamentation, the old chapel is in need of repair. Large areas of plaster have

spalled from their adobe base.

[Jesse L. Nusbaum, Museum of New Mexico]

4–3

El Rosario Chapel

The apse of the old structure, today the eastern

transept, shows the original reredos, although it lacks

religious images.

[1986]

4–4

El Rosario Chapel

The adobe chapel was reduced to the status of an appendage to the new

nave when the building became part of a national cemetery.

[Paul Logsdon, 1980s]

4–5

El Rosario Chapel, Plan

[Sources: Field measurements by Marc Treib and Dorothée Imbert,

1987; and Susan Lopez, 1986]

4–6

El Rosario Chapel

The early-nineteenth-century chapel now serves as the sanctuary and transepts of the renovated structure. The

windows were probably cut around 1914 to address the new axis created at the time of renovation.

[1986]

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

1795?; 1808?–1821

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe is one of those adobe churches that has changed so radically over time that recognizing it in uncaptioned photographs would be difficult. The church appears neither on the 1766 map by José de Urrutia nor in the Domínguez report of about the same time. The exact date of its origin remains a bit of a mystery, although it was probably built at the very end of the eighteenth or early in the nineteenth century because a license was issued for its construction in 1795.[1] The map of the city by Jeremy Francis Gilmar drawn in 1846 shows the plan of a cross-shaped church and campo santo on the site, but no tower. (The Castrense chapel is also shown without towers, however, suggesting that the church was rendered symbolically rather than literally.)

Father James H. Defouri, who administered the parish in the later nineteenth century, may have been the source for Ralph Twitchell's claim that the church dates from before the Pueblo Revolt: "[In 1680] Guadalupe being somewhat out of town fared better for a while, but was sacked the following year."[2] Except for these undocumented assertions, there is no recorded evidence of the church's existence or description until 1821, as Kubler noted, when it was visited by Agustín Fernández after Mexican independence. Having been omitted in Pereyro's inventory of 1808, Kubler ascribed its construction to the period between 1808 and 1821.[3] From then on the church suffered the normal pattern of ups and downs.

When the Americans took control of the city in 1846, the year of the Gilmar map, the church was sadly dilapidated, although Abert reported that it had been in use until as late as 1832.[4] An 1886 map now in the Museum of New Mexico illustrated the church in a vignette with typical New Mexican massing, stepped up at the choir and transepts to admit a transverse clerestory, and, of course, made of adobe. There was a three-stage tower similar to the old bell tower at San Miguel that was destroyed in the 1880s, but it was placed off center, to the east of the main door. Lieutenant Bourke confirmed the church's ruinous condition in 1881:

It shows great age in its present condition quite as much as in the archaic style of its construction. The exterior is dilapidated and time-worn; but the interior is kept clean and in good order and in very much the condition it must have shown generations ago. The pictures are nearly all venerable daubs, with few pretensions to artistic merit. At present, I am not informed upon this point and cannot speak with assurance, but I am strongly suspect that most of them were the work of priests connected with the early

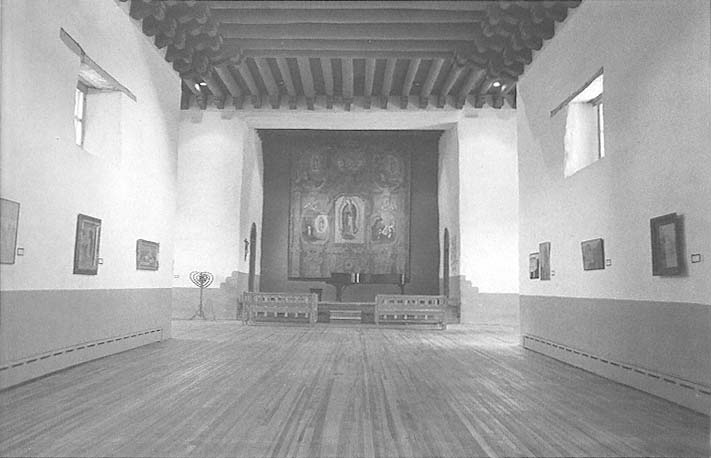

5–1

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

The renovations of the 1970s converted the church into a performing arts

center and gallery, although there were no attempts at a precise historical

restoration.

[1981]

5–2

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

1881

The single tower, with its massive base, cast the church into asymmetry; its stepped profile resembled the old San

Miguel chapel.

[W. H. Jackson, Museum of New Mexico]

missions of Mexico. Many of the frames are tin. The arrangement for lighting this chapel are the old-time tapers in tin sconces referred to in the description of San Francisco and San Miguel. The beams and timber exposed to sight have been chopped out with axes or adses, which would seem to indicate that this sacred edifice was completed or at least commenced before the work of colonization had made much progress.[5]

At that time its only official services were held on December 12 at the annual festival of Our Lady of Guadalupe.[6] The church also seems to have been used for Protestant services in the 1880s under pressure from Anglo immigrants.

The growth of mining in northern New Mexico at that time also brought an influx of Catholics who, although centered around Cerrillos, petitioned for an English-speaking congregation in Santa Fe. About 1881 Reverend James H. Defouri was placed in charge, and like Saint Francis centuries before, Defouri energetically went about putting God's house in order. L. Bradford Prince noted that new windows, made available by the railroad, were installed and that a typical, although light-smothering, pitched roof of shingles was added. Capping the new incarnation was "a wooden spire of the strictest New England meeting house pattern in the place of the venerable tower."[7] Pews graced the new wooden floor. The transformation was so complete that had it been worked on a child, even its mother would not have recognized it—which was, no doubt, the intention.

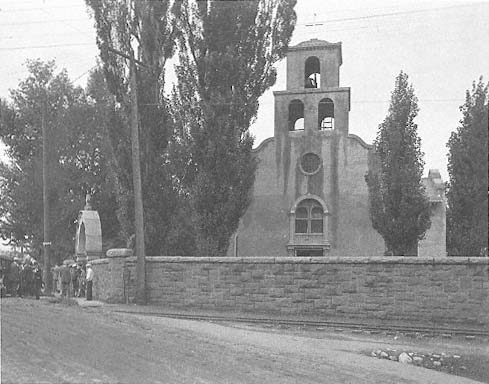

A fire in 1922 destroyed the roof timbers of the sanctuary and transepts as well as the alien steeple. By then the popularity of the California Mission style had begun to work its romantic magic on the populace, and Guadalupe was accordingly rebuilt with curved shoulders supporting a two-staged tower with proper arched openings. Although not accurate in terms of historical precedent—as was clearly visible in the sloped tile roof—the new form fit better into the architecture of Santa Fe than had its dilute Gothic predecessor. On the interior a single arch spanned across the altar, somewhat elevating the character of the historic adobe structure.

5–3

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

April 1881

Like the exterior of the church, the interior underwent extensive changes

at the end of the nineteenth century. In this early photo the accretions

and clutter of votive offerings are apparent.

[Ben Wittick, Museum of New Mexico, School of American Research

Collections]

5–4

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

circa 1887

At the end of the 1880s the new pitched roof and belfry gave the church

the look of a New England schoolhouse.

[F. A. Nims, Museum of New Mexico]

Guadalupe became an auxiliary of the cathedral parish in 1918, but its status as a separate congregation was restored in 1931. A new church was constructed south of the original structure in a sympathetic, if not historicist, style. What was to become of the old building? For some time it functioned as a chapel. Through the initiative of Archbishop Robert Sánchez, however, the old church was restored for use as a museum of Spanish Colonial art and, when appropriate, as a performance center for chamber music and recitals. The Santa Fe architectural firm Johnson-Nestor directed the restoration, which was undertaken during the years 1976–1978.

The building has not been restored but has been significantly remodeled; the tile pitched roof still conceals the clerestory. The tower has been revised to a more severe form, with square openings using wooden lintels to replace the former arches. Throughout the interior and exterior the inappropriate aspects of the 1920s rebuilding have been removed and the architectural entirety simplified. A small watercourse leads toward the river as a tentative gesture toward establishing a link between the old church and downtown. While this remodeling is neither complete nor accurate in an archaeological sense, the current state could best be termed sympathetic and successful in feeling, if not in form.

5–5

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

circa 1920–1925

By the late 1920s a central belltower had replaced the Anglo belfry, and a California Mission

style had glazed the church.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

5–6

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, Plan

[Sources: Plan by Johnson-Nestor, Architects; and measurements

by Susan Lopez, 1987]

5–7

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

circa 1920

Victorian clutter has superseded the Hispanic; but the arch spanning the chancel reveals an influx of Anglo

architectural taste.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

5–8

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

The state of the interior after renovation: Spanish colonial architecture in a simplified form.

[1981]

Nuestra Señora de la Luz [La Castrense]

1754(?)–1761; deconsecrated c. 1859

Cristo Rey

1940

Architect: John Gaw Meem

Although the Laws of the Indies did not specify that a church be built prominently on the plaza, neither did they proscribe its construction. And because the plaza was originally conceived primarily as a military space, it is not surprising that the chapel of the military confraternity should be built directly fronting the parade ground. It took some time, however —about a century to be more precise—before a chapel was built on the site.

During his term as governor (1754–1760), Francisco Antonio Marín del Valle purchased a lot on the south side of the plaza, facing the Palace of the Governors "between two houses of settlers."[1] He raised a chapel there for the sum of 8,000 pesos. Captain as well as governor, he had an interest in the project that probably exceeded piety. On this site a structure was erected with its facade toward the plaza, following the configuration of nave and transepts common to the Spanish towns of northern New Mexico.

As early as the 1620s Benavides had reported the paucity of church buildings in Santa Fe because the size of the population was small: "The Spaniards . . . may number up to 250. Most of them are married to Spanish or Indian women or to their descendants. With their servants they number almost 1,000 persons. They lacked a church, as their first one had collapsed." To rectify the problem, he had "built a very fine church for them, at which they, their wives and children, personally aided me by carrying the materials and helping to build the walls with their own hands."[2]

By the time of Bishop Tamarón's visit a century and a half later, the population had increased by about one-half: "I have confirmed 1,532 persons in the said villa, [but] I am convinced that the census they gave me is very much on the low side, and I do not doubt that the number of persons must be at least twice that given in the census."[3] Public worship was limited to the nearby Parroquia and the chapel of San Miguel across the river. Construction of the Castrense chapel was well under way, although building would not be completed for another year. Unlike the majority of churches in New Mexico at the time, this chapel would be highly embellished, receiving praises even from critical Mexican visitors. Tamarón witnessed the event:

In the plaza, a very fine church dedicated to the Most Holy Mother of Light was being built. It is thirty varas long and nine wide, with a transept. . . . The chief founder of this church was the governor himself, Don Francisco Marín del Valle, who simultaneously arranged for the founding of a confraternity which was established while I was there. I attended the meeting and approved everything.[4]

6–1

La Castrense Chapel

This redrawn detail based on the Gilmer map of 1846,

shows the Castrense chapel just south of the plaza. The

Parroquia (today the Cathedral of Saint Francis) lies to

the right of the original plaza, already filled in with private

buildings.

Written by Marín del Valle himself, the organization's constitution was approved by Bishop Tamarón during his visit, indicating that the founding of the confraternity postdated the chapel already under construction. Given what Domínguez termed "the fervent and glowing order of his devotion," it is no surprise that Marín del Valle was elected the first "Hermano Mayor," or "as we should now say, first president of the Society."[5] Work on both the altar screen and the body of the chapel continued during Tamarón's visit and were officially consecrated on May 24, 1761. Although officially the chapel was dedicated to Nuestra Señora de la Luz, or Our Lady of Light, it was usually known as La Castrense in reference to the military confraternity.

A considerable sum was to have been expended on the chapel interior, although the exterior remained the simple mud-plastered adobe common to the province. Most notable among the furnishings was the elaborate altar screen that filled the rear wall of the chapel. Under Marín del Valle's patronage, Mexican stone carvers, perhaps from Zacatecas, were imported to handle its crafting. "Eight leagues from there," Tamarón recorded, "a vein of very white stone had been discovered, and the amount necessary for the altar screen large enough to fill a third [of the wall] of the high altar was brought to this place. This then was carved."[6]

Domínguez, exceptionally, was just as impressed during his visit of 1776. His description noted that the structure "has walls about a vara thick. Its door faces north, and a little above it is a white stone medallion with Our Lady of Light in half relief. At the very top of the flat roof are three arches, a large one in the center with a good middle-sized bell, and a small one on either side without anything." A clerestory and a choir loft, both supported by "wrought beams" on corbels, were typical, although the carving was more elaborate than usual. Three windows faced east. Unlike the more normal wood-fronted steps into the chancel of most churches, however, "the ascent to the sanctuary consists of four octagonal stairs of white stone. The whole sanctuary is tiled with said stone, and there are three sepulchers in it."[7] The sacristy adjoined the east transept, its window to the south.

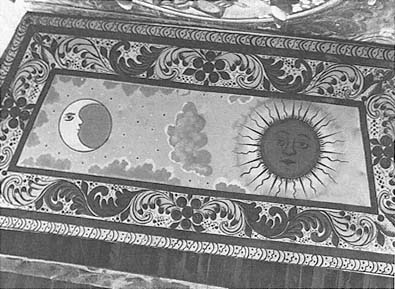

The focus of the interior was the altarpiece that dominated the rear wall.

The altar screen is all of white stone . . . very easy to carve. It consists of three sections. In the center of the first, as if enthroned, is an ordinary painting on white canvas with a painted frame of Our Lady of Light, which was brought from Mexico at the aforesaid Governor Marín's expense. . . . On the right side

of this image is St. Ignatius of Loyola, and on the left St. Francis Solano. Toward the middle of the second section is St. James the Apostle, and beside him, St. Joseph on the right and St. John Nepomuk on the left. The third section has only Our Lady of Valvanera, and the Eternal Father at the top.[8]

Originally, the entirety was polychromed in the tradition of the wooden altarpiece, and the architectural framework of the screen was filled out with Arabesque columns and entablatures. The effect, Domínguez noted, was that the altar screen "resembles a copy of the facades which are now used in famous Mexico."[9] Two altars of stone, like the altar screen, stood in the transept. "Its interior is very attractive," Domínguez said in summation.[10] Given that his opinion of the villa of Santa Fe was that it "lacks everything," this was no mean compliment.[11] The effect of the altarpiece was never equaled in colonial New Mexico, although its design served as the basis of many painted altar screens thereafter.[12]

The chapel was set back from the south limit of the plaza, fronted by a campo santo apparent in the simple Urrutia map of 1768. Six years later de Morfi provided fewer details but showed a bit more respect for the villa: "The plaza," for one, "was square and beautiful. A chapel consecrated to Maria Santisima de la Luz [Most Holy Mary of the Light] also adorns it [the plaza], where was established the parish of the military which a religious served since 1779, the year [of its erection and other private buildings]."[13] As the chapel was completed in 1761, this was either an error or a reference to a renovation, possibly the construction that added the two towers and balcony to the north facade, commented on by nineteenth-century observers.

By the end of the century the walls and roof had badly deteriorated, and in 1805 Fray Francisco de Hozio requested funds to make "repairs necessary for the decency of the divine worship."[14] The official visitor, Juan Bautista de Guevara, in a lengthy report, was "deeply saddened by the 'ruinous and lamentable state' to which the confraternity had sunk." His document, however, did record that "across its entire facade looking toward the plaza there is a gallery of six sections with columns and a wooden roof; two small adobe towers with wooden tops, all old and falling down."[15]

Services were well attended and treated with some degree of pomp. "During the first government of Manuel Armijo (1827–29), he went regularly with the whole garrison force of Santa Fe in full uniform to attend services there."[16] Although the chapel remained intact through the 1830s, this was to be the last period during which most of its

6–2

La Castrense Chapel

The upper portion of the stone reredos sponsored by Antonio Marín del

Valle, now in the church of Cristo Rey.

[1986]

previous glory remained. When the new republic of Mexico withdrew stipends for military chaplains, the Castrense lost its congregation.[17]

James J. Webb, a trader visiting Santa Fe in 1844, wrote that the "old church about the centre of the block on the south side of the plaza . . . has not been occupied as a place of worship for many years."[18] The chapel was not to have a quiet end, however—at least not yet. The military continued to support its upkeep with occasional repairs, however sporadic. At the time of the American entry shortly thereafter, the building was in derelict condition. Lieutenant Abert described the interior as having been

the richest church in Santa Fe. . . . There is some handsome carved work behind the altar, showing a much higher order of taste than now exists. . . . One finds the bones of many persons scattered about the church. These belong to wealthy individuals who could afford to purchase the privilege of being beneath the floor where so many prayers were offered up; but they have not found as quiet a resting place as the poor despised publicans. The roof of this church fell in a few years ago and it has not been used since.[19]

The United States Army acquired the use of the church, repairing the roof and using it for storage until 1851, when Justice Grafton Baker sought a suitable location to conduct due process. He eyed the property and began the process of adapting the storage buildings as a court of law. Surprisingly, given the dilapidated state of the chapel, he met with considerable resentment from the citizens, who cited the burials within the building as reasons not to use the chapel for civil purposes. Baker held his ground and the controversy grew. After one judicial session, however, an agreement was struck that passed the chapel back to the diocese. Bishop Lamy, after receiving the keys to the building, called for a subscription to repair the chapel. His efforts were successful, and the building was at least partially restored during the next few years.

Lamy had problems of his own. As an avid supporter of education he had formulated a rigorous program of instruction and school building. He had also set his mind on the construction of a stone structure to replace the adobe Parroquia that was now his cathedral. Both programs required money. In an effort to raise the necessary capital for the repairs and land for a school, he sold the Castrense in 1859 to Don Simón Delgado, who built a house on the site. In turn Lamy was given $2,000 by Delgado and a plot of land for Saint Michael's College.[20] Parts of the structure remained until 1955, when

6–3

La Castrense Chapel

In this photo taken around 1877 the old chapel has been converted into

a store, with a latticed terrace addition at the second-floor level. The

beam ends still protrude through the adobe wall, and the new cathedral

is rising at the end of San Francisco Street.

[Benjamin H. Gurnsey, Museum of New Mexico]

demolition of the chapel was complete.[21]

The noted stone altarpiece of Nuestra Señora de la Luz was moved first to the cathedral, where it was kept until the church of Cristo Rey was built in the late 1930s. There it remains, but with only traces of its original polychromy, its force partially diminished by the much larger scale of the new structure.

Three factors contributed to the construction of the new church. The first was the interest of the Committee for the Preservation and Restoration of New Mexico Mission Churches in finding a new home for the stone altar screen from the Castrense. Since the 1860s the screen had been "stored" in a space behind the altar of the cathedral in a state of benign neglect. Second, when Reverend Rudolf Gerken became archbishop of Santa Fe in 1933, he found the need for an additional parish on the city's east side. A site was purchased on upper Canyon Road, John Gaw Meem's firm receiving the commission for design in 1939. The third factor was the four hundredth anniversary of Coronado's expedition through the Southwest. At a dinner in the cathedral rectory on April 6, 1939, Archbishop Gerken announced the commencement of the project: "We shall build a memorial to the Coronado Centennial in the form of the most beautiful church in the Southwest. This memorial will become a new parish."[22] For a project of this size, the design process must have proceeded rapidly, although there never seemed to have been any question as to the style of the structure.

The appearance of the church is traditional, but its form somewhat belies its construction. Although Cristo Rey is principally an adobe structure—with the number of bricks estimated at between one hundred fifty and one hundred eighty thousand—it is not a pure bearing-wall building. In response to the loads that the walls had to carry and the span of the nave, the adobe structure was augmented by a structural steel frame that not only reinforced the walls but also carried a portion of the vigas of which the roof was made.

The craft is of the highest order throughout. The corbels supporting the vigas are finely carved, and the split juniper logs, or cedros , that form the ceiling are carefully fitted. The exterior departs from the rigid symmetry of the interior composition, freely utilizing inspiration or forms from a number of historical structures. As Bainbridge Bunting noted, "It has the grand scale and at least one tower of Acoma, the balconied facade of Trampas, the transepts of the old Parroquia of Santa Fe, and the effective transverse clerestory of Santa Ana."[23] The totality escapes the level of pastiche, however, and evidences a coherent architectural idea executed with understanding and skill. The church received the archbishop's blessing on January 1, 1940, and was formally dedicated later that year on June 27.

When judged against the ideal, the church as the home for the Castrense altarpiece has two short-comings. The first is the size of Cristo Rey, which is of a grander order than the historical chapel. The effect of the reredos seen from the distance, surrounded by larger walls, is just not the same, being diminished by the size of the space. The second is the greater level of illumination, which from windows as well as skylights at times undermines the drama created when only a clerestory transmits light. Despite these minor criticisms, the fine Castrense reredos is again accessible to the public, and it lives once more within a church, not a museum.

6–4

Cristo Rey

In spite of the large scale of the church, the effect of the clerestory light falling upon the reredos remains effective

and dramatic.

[1986]

6–5

Cristo Rey, Plan

[Sources: sketch plan by John Gaw Meem, University of

New Mexico Library Special Collections; and measurements

by Dorothée Imbert and Marc Treib, 1986]

6–6

Cristo Rey

May 1942

Shown three years after its completion, the church displays far greater subtlety in its mud plaster modeling than in

today's hard stucco.

[New Mexico Tourism and Travel Division]

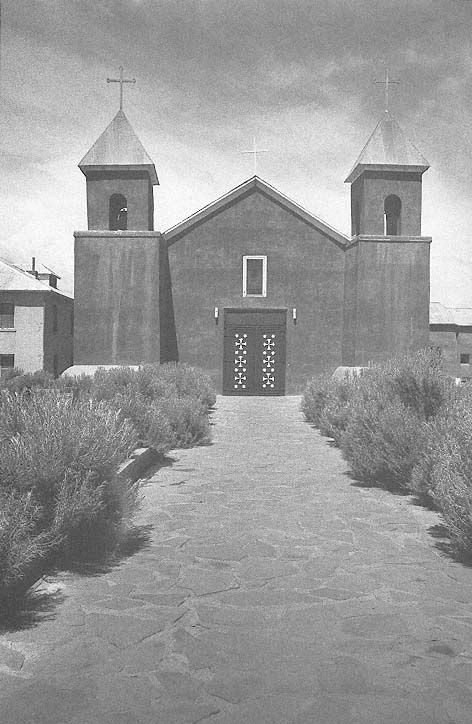

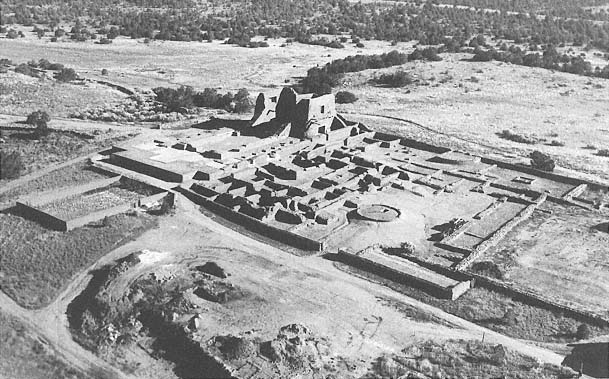

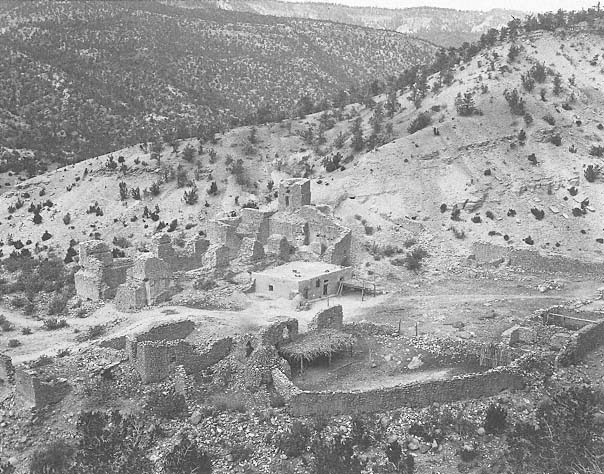

NORTH OF SANTA FE

Tesuque Pueblo:

San Diego

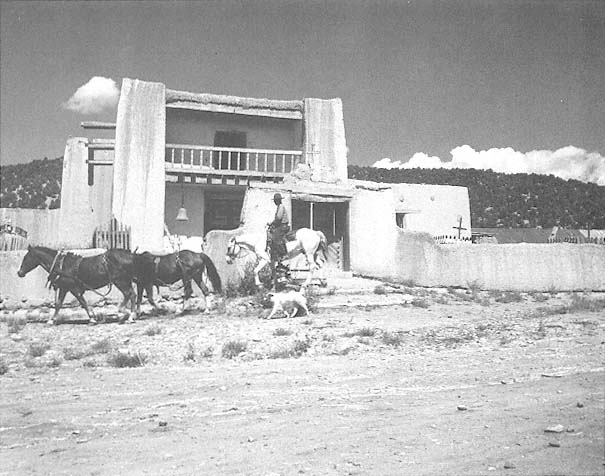

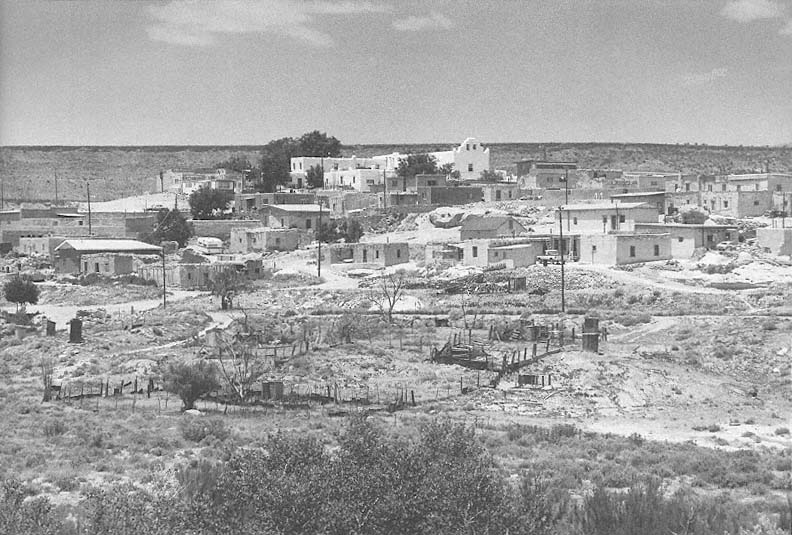

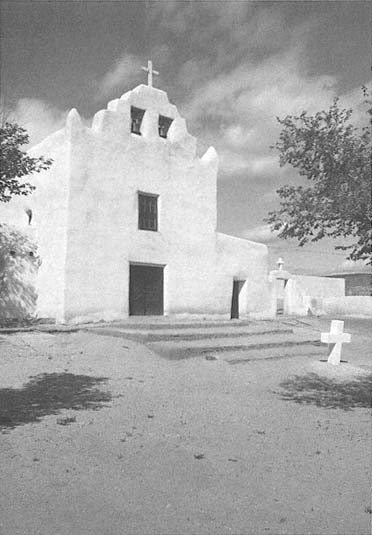

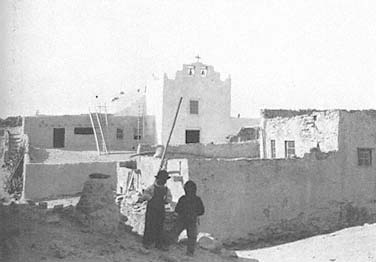

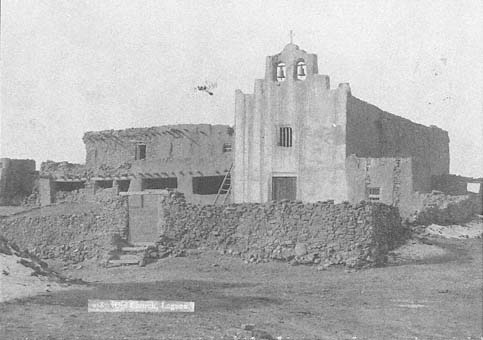

(1620s?); 1706; c. 1914

Tesuque, the first of the pueblos north of Santa Fe, is one of the smallest of the Tewa group: its population was listed as 281 people in 1973. In contrast to the larger agglomerations of living units, such as the multitiered blocks at Taos or the more rambling configurations at Isleta, Tesuque's form is unequivocal and centralized. Constantly deteriorating, although continually being restored, the pueblo is a simple and singular statement of collective building. Federal housing policy enacted in the mid-1960s produced single-family detached houses planned in patterns at odds with the traditional collective forms. The results are seen on the periphery of the pueblo.

The plaza, at the center, is laid out east-west, which prompted one set of authors to associate orientation with the configuration of the land.[1] Ralph Knowles claimed that this alignment, which creates a southern solar exposure, was a fine-tuning of the architecture to exploit the thermal properties of adobe mass.[2] There is probably at least an element of truth in both explanations, although in many cultures the east-west axial plan also objectifies the rising and setting of the sun and its movement across the skies.

Tesuque pueblo exhibits one of the tightest architectonic compositions, more or less a single rectangle with parts of its eastern block stacked in two stories. Archeological evidence has established occupation on the site as early as A.D . 1200. According to Bertha Dutton, the pattern of this "prehistoric" community bears a recognizable architectural relation to earlier settlements such as those at Mesa Verde.[3]

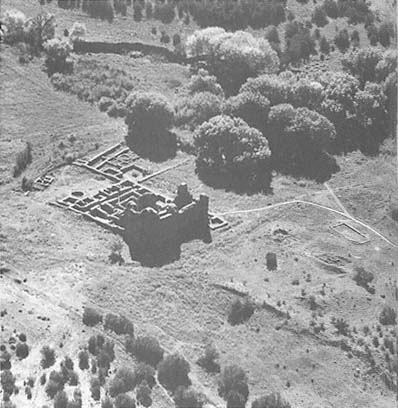

Tesuque is also unique in that its church, dedicated to San Diego, sits directly on the plaza. This may not have always been the case, however. Frederick Hodge believed that the current village is sited three miles east of its pre–Pueblo Revolt location,[4] which would suggest that the pueblo either occupied a site that had been inhabited in the distant past or established a new pueblo and mission after the Reconquest.

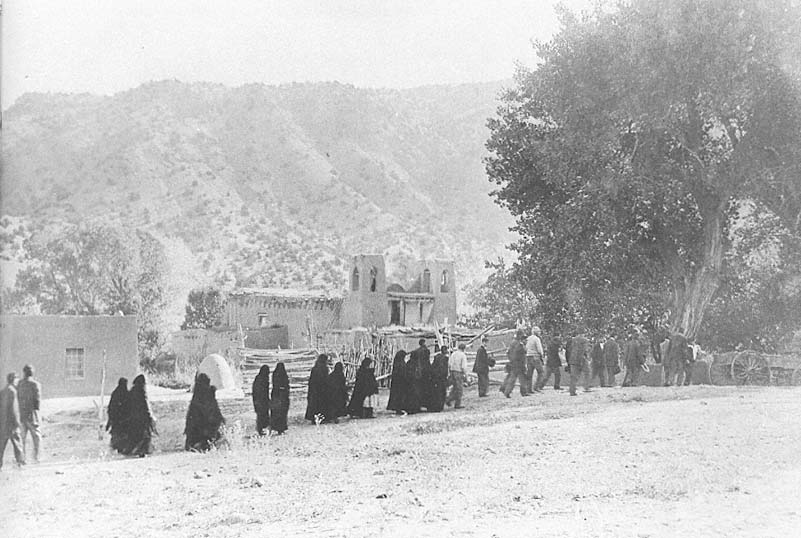

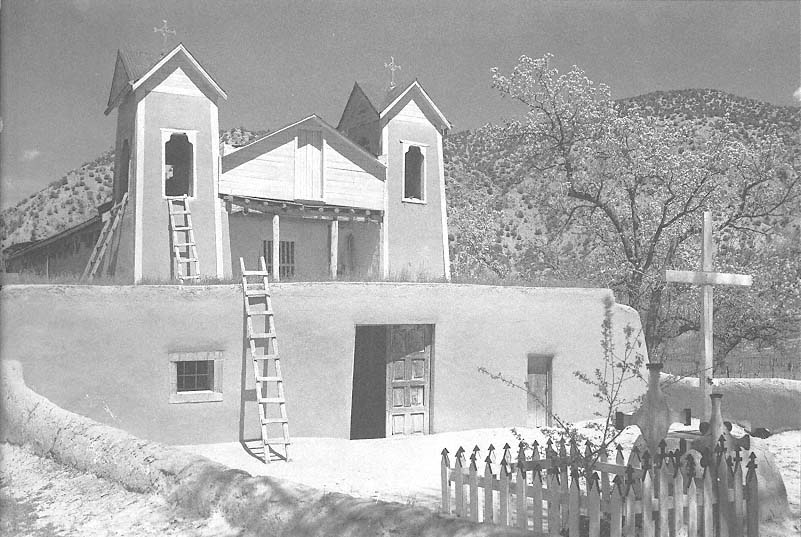

The original church was dedicated to San Lorenzo, and its founding is credited to the indefatigable Benavides in the late 1620s. But "on August 10, 1680, the feast of San Lorenzo," Paul Walter narrated, "the day of the Pueblo uprising and martyrdom of the Franciscan missionaries, Fray Tomas [at Tesuque] was killed and the church burned."[5] Perhaps negative associations with the saint or the saint's day led to the reattribution to San Diego when the church was reestablished in 1695, construction having been supervised by Fray José Díez. Substantially deteriorated by 1745, it was rebuilt under the guid-

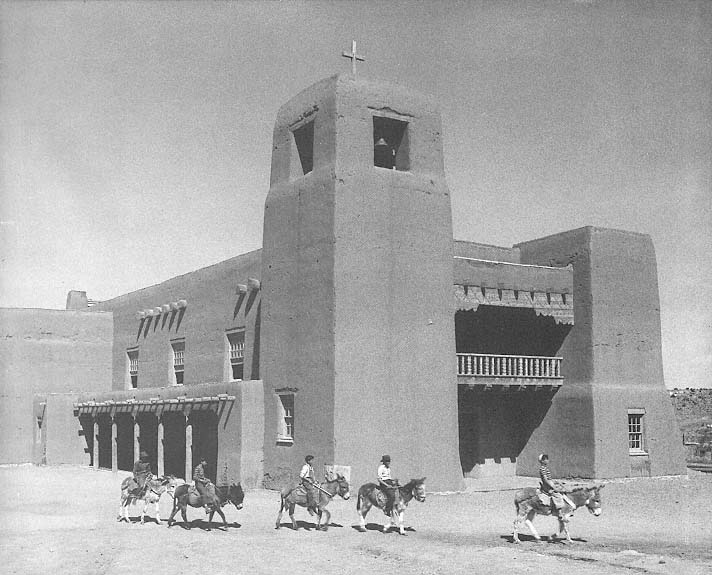

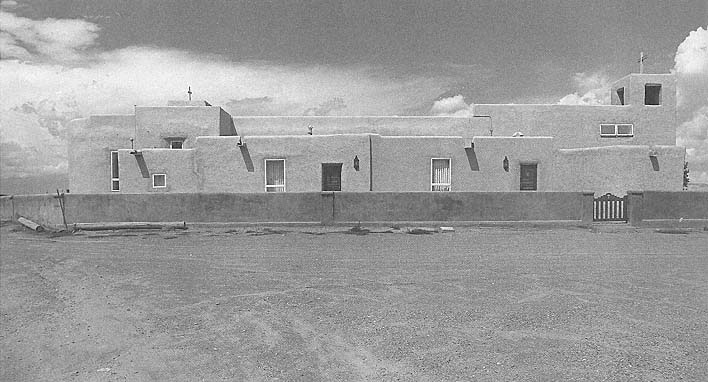

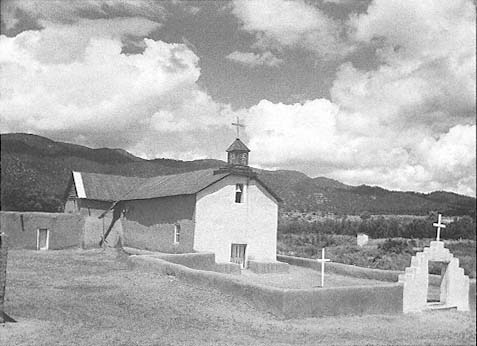

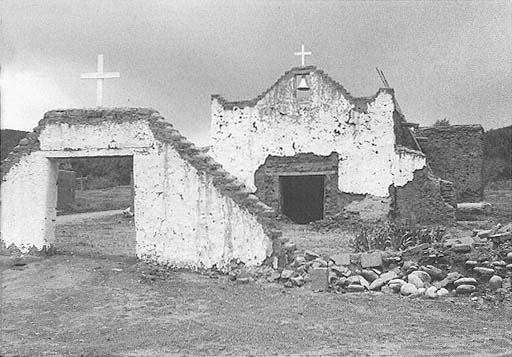

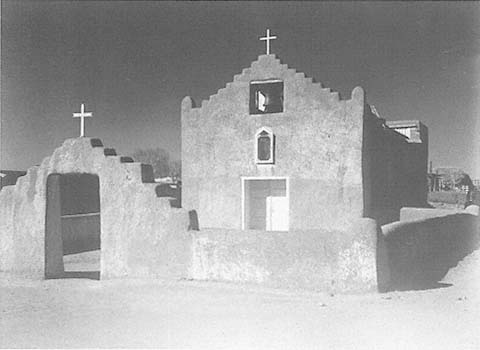

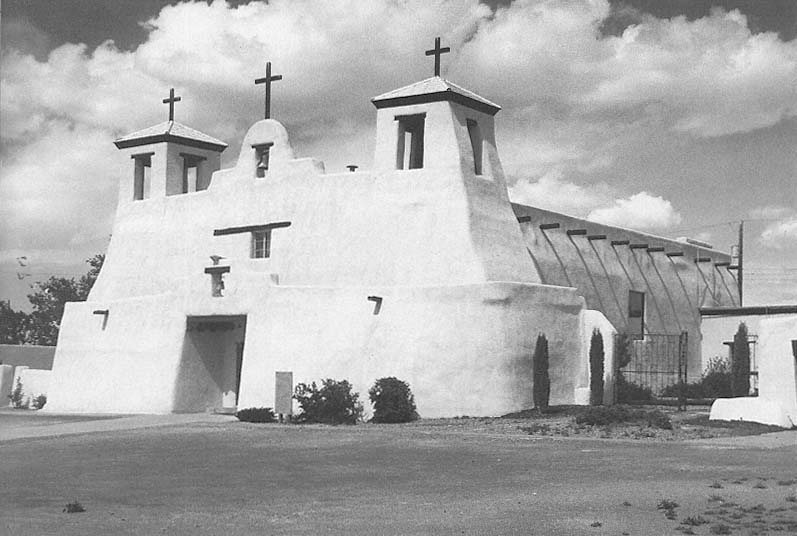

7–1

San Diego

The hard plaster is cracked and peeling, spiting repairs made to maintain its integrity. A small bush reclaims the

summit of the facade.

[1981]

ance of Fray Francisco de la Concepción, who was often at odds with the colonial government. Typically, the disputes regarded the use of Indian labor.[6] The mission remained a visita of Santa Fe into the eighteenth century.

Kubler believed that the new church was built prior to 1706—a common dating—and that this was probably the church de Morfi described in 1782 by saying, "The religious of Santa Fe have a church there and an adequate dwelling place . . . although of adobe and very poor."[7] Bishop Tamarón left a sociological, rather than a physical, picture of the mission. Writing in 1760, he described the church as a visita of Santa Fe and bestowed a blessing of sorts by saying that "these Indians are more civilized (than the Comanche to whom they are compared), but he was troubled by their lack of confessions.[8] Unfortunately, he added little else except that there were thirty-one families with 232 people. The 1750 census tallied a population of forty-four households with 171 people.[9]

By the time of the Domínguez visit in 1776, the population stood at forty-five families with 194 persons.[10] Domínguez wrote that since 1769 the church had been served by a priest from Nambe, although in a note Adams and Chavez indicated that church records listed a resident priest at the pueblo between 1729 and 1772.[11] Catechism was delegated to the fiscal mayor , an Indian appointed to assist the priest and in this case act as his surrogate, but Domínguez seemed pleased to report that "on Saturdays and feast days the whole pueblo gathers in the church at the peal of the bell to recite the rosary."[12] The priest from Nambe, however, came to hold services at Tesuque on feast days and sometimes heard confession. On other occasions the Tesuque congregants traveled to Nambe for mass.

At that time the disposition of the pueblo differed from what we see today. The church was not directly on the plaza but was separated from it by a block of buildings that intervened between the church/convento and the plaza. Perhaps at that time the church was still not completely accepted into the community. "The planting for the father is entrusted to the pueblo up to the harvest, and since stealing and carelessness prevail, it goes ill for the priest," Domínguez revealed. The congregation seemed to have had a different agenda. After a description of the pueblo blocks, Domínguez noted, "It is obvious from the foregoing that the church is outside this little plaza, and this is true. Yet it stands at the end of a blind alley, for there are some small new houses a little farther down facing the back of the aforesaid tenement."[13] Apparently the form of

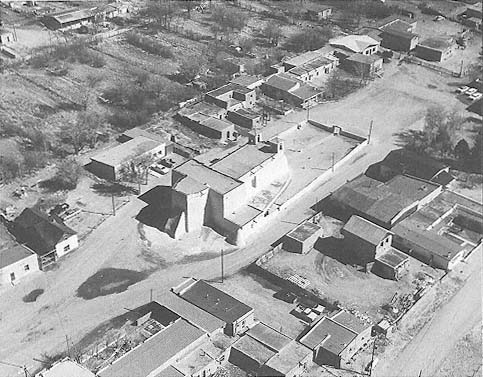

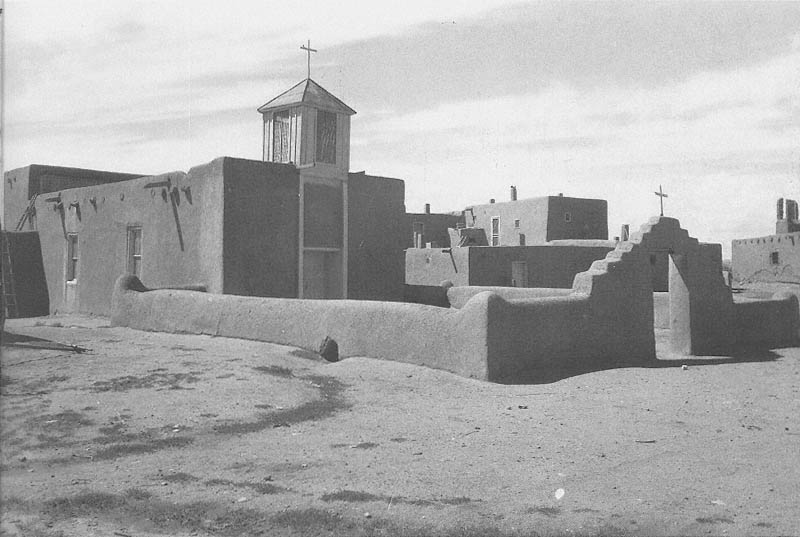

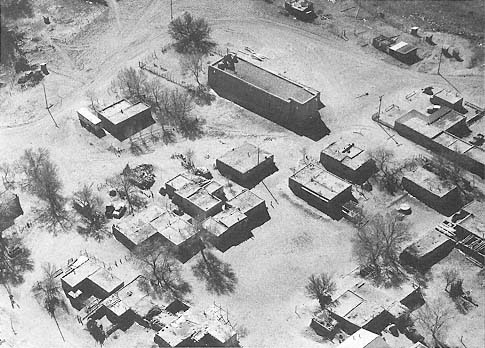

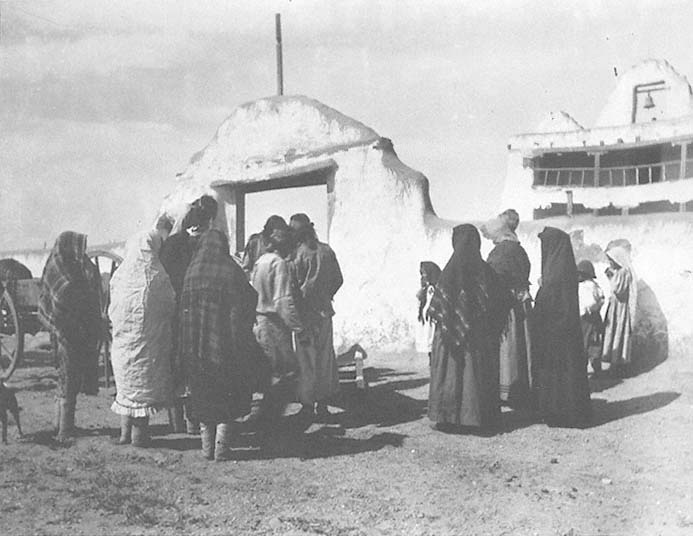

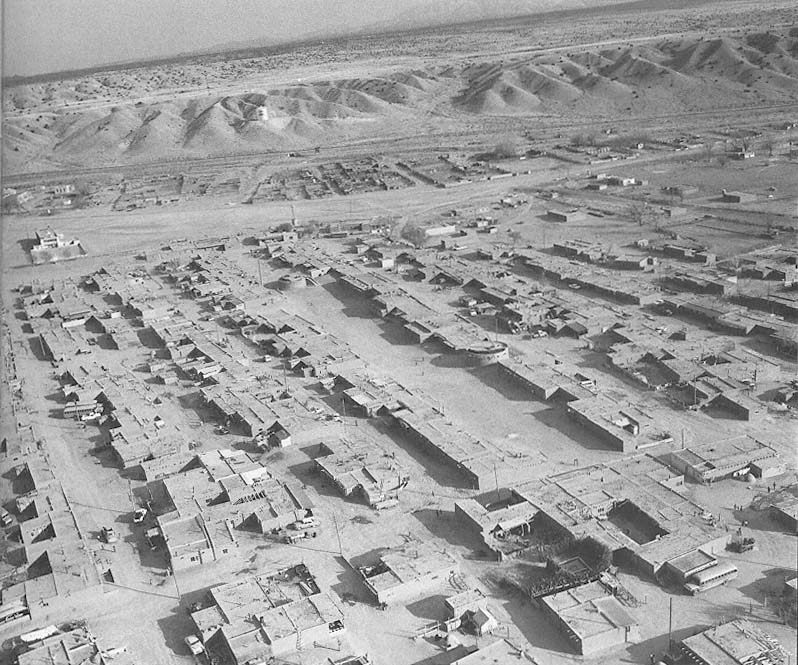

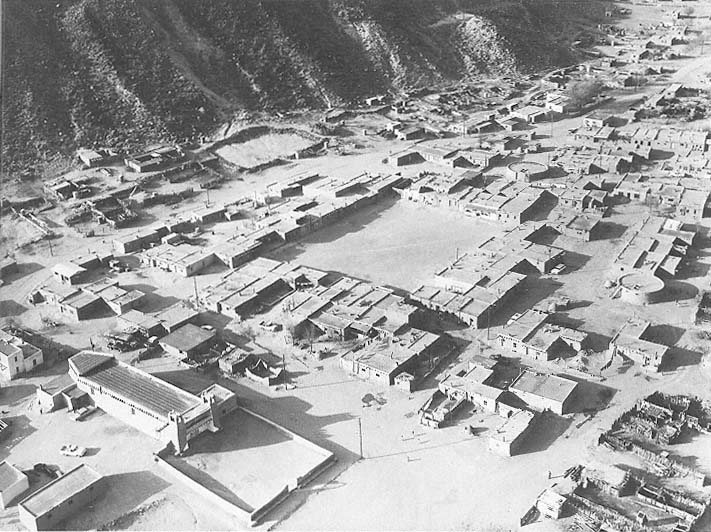

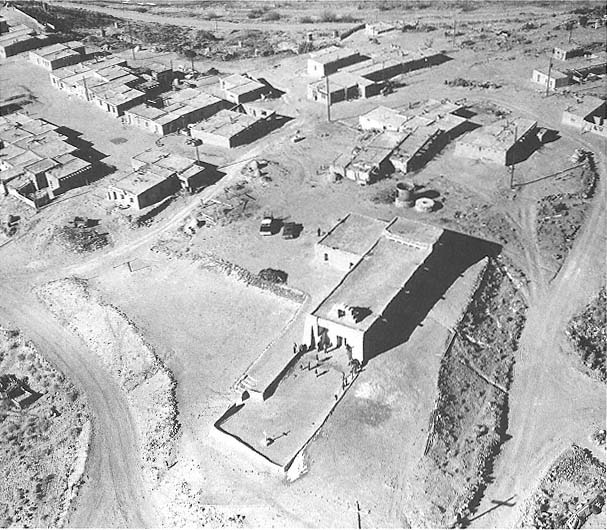

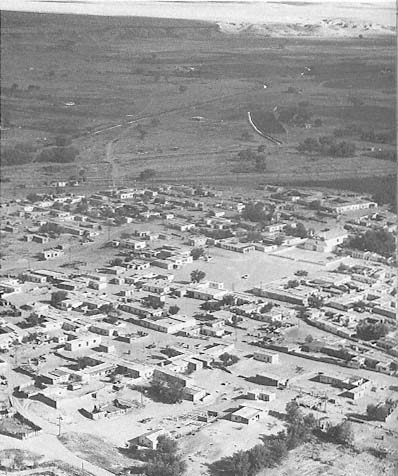

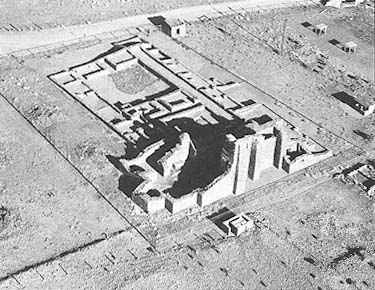

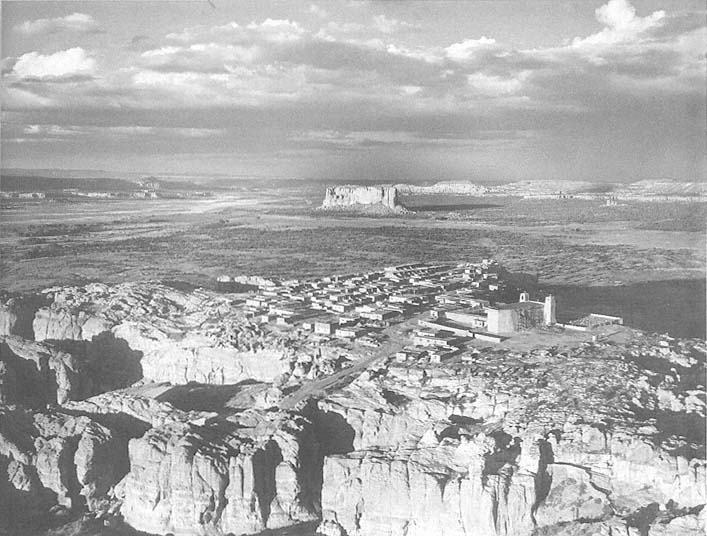

7–2

Tesuque Pueblo

The pueblo from the air. The church of San Diego is in the upper center,

one of the few pueblo churches located directly on the main plaza.

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

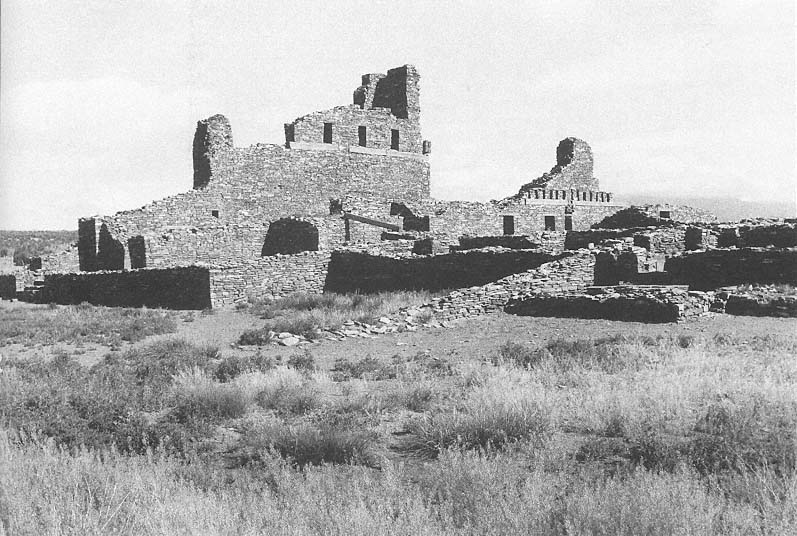

the plaza as a defined rectangle was not regarded as sacrosanct; its presence was more often suggested than physically defined in the European tradition.