The Aluminum Garden

If the first section of Garrett Eckbo's career culminated in the public work of the depression and the war years, its second era reached a high point in the Forecast Garden for the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA ). The Wonderland Park development, in which the garden was located, grew from the cooperative plans for the ill-fated Community Homes in Reseda (see following essay). Stymied in the San Fernando Valley by federal loan policies, a number of families regrouped and purchased a tract of land in Laurel Canyon in western Los Angeles.[98] Since the streets had been plotted during an prior attempt at development, Eckbo could provide little comprehensive planning, although he did prepare a planting scheme—and he did design a number of the community's private gardens and their front yards. One commission in particular allowed Eckbo to realize his ideas on a smaller scale, while extending the limits of materials acceptable in garden construction: the clients would be the family of the landscape architect.

The residence for Arline and Garrett Eckbo was designed by Joseph van der Kar in the modern southern California idiom, in a tone that was neither formulaic nor assertive. Eckbo sought to complement the interior of the house outdoors, with spaces that extended the boundaries of the building toward the hillside. The site occupied land at the intersection of two valleys and required considerable grading to establish suitably level terrain for the house. From the start, Eckbo proposed a series of garden plans, all of which—typical of most designers—he left unrealized, secretly hoping perhaps that the next idea would be even better, and that more money would have accrued for implementation. An early scheme (undated) used a series of geometric shapes, including a lozenge-shaped pool, as fragments set within the graded frame [figure 76]. Sometime in 1956 the Aluminum Company of America, through its advertising agency,

I

Freeform Park, Washington, D.C. Site plan. Student project at Harvard University, 1937.

Watercolor on paper.

[Documents Collection ]

II

Arvin Camp, Farm Security Administration,

circa 1940. Vernon DeMars, architect.

[Garrett Eckbo ]

III

Mar Vista (Modernique Homes),

Los Angeles, 1948. Gregory Ain, architect.

The Beethoven Street landscape today.

[Marc Treib, 1996 ]

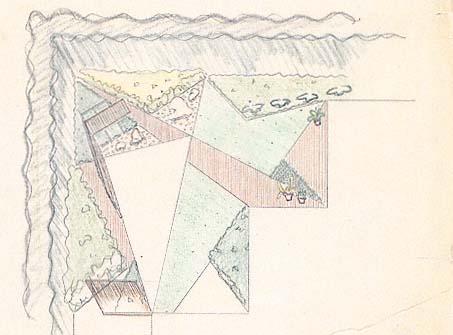

IV

Jones garden. Axonometric study. Los Angeles, late 1940s.

Colored pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

V

Sanford garden, Los Angeles, 1958.

[Garrett Eckbo ]

VI

Goldin garden. Laurel Canyon,

Los Angeles, mid-1950s.

[Garrett Eckbo ]

VII

Firk garden. Preliminary plan. Los Angeles, 1952. Colored pencil on diazo print.

[Documents Collection ]

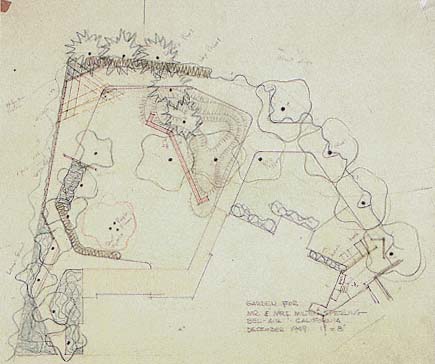

VIII

Sperling garden. Bel Air, 1949. Colored pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

IX

Edmunds garden. Pacific Palisades, 1956.

[Garrett Eckbo ]

X

Cole garden. Beverly Hills, early 1950s.

[Garrett Eckbo ]

XI

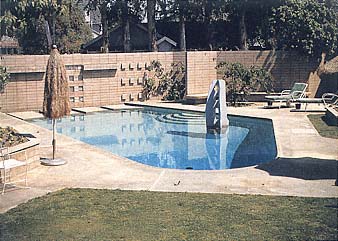

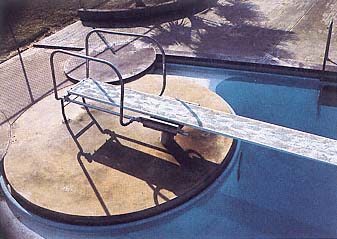

Cranston swimming pool. Los Angeles, late 1950s.

[Garrett Eckbo ]

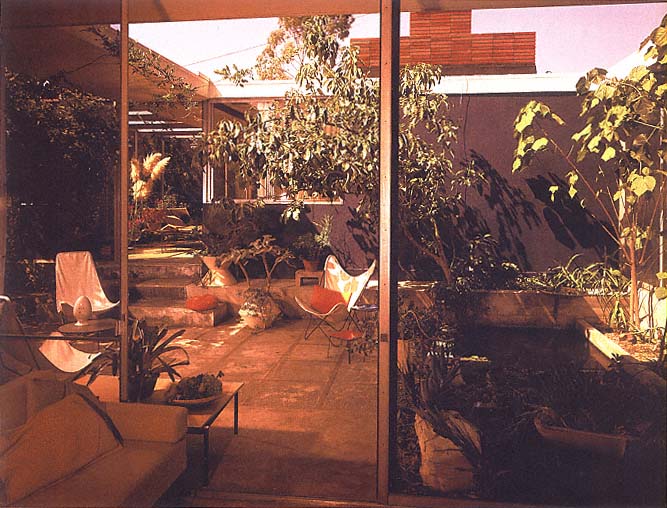

XII

Shulman garden. Court. Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, 1950. Raphael Soriano, architect.

[Julius Shulman ]

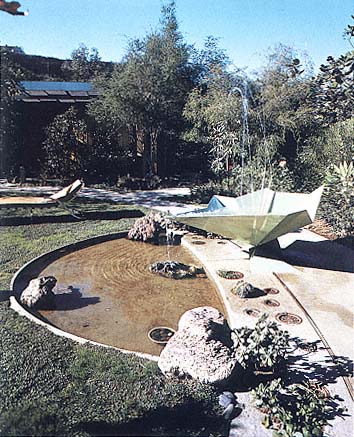

XIII

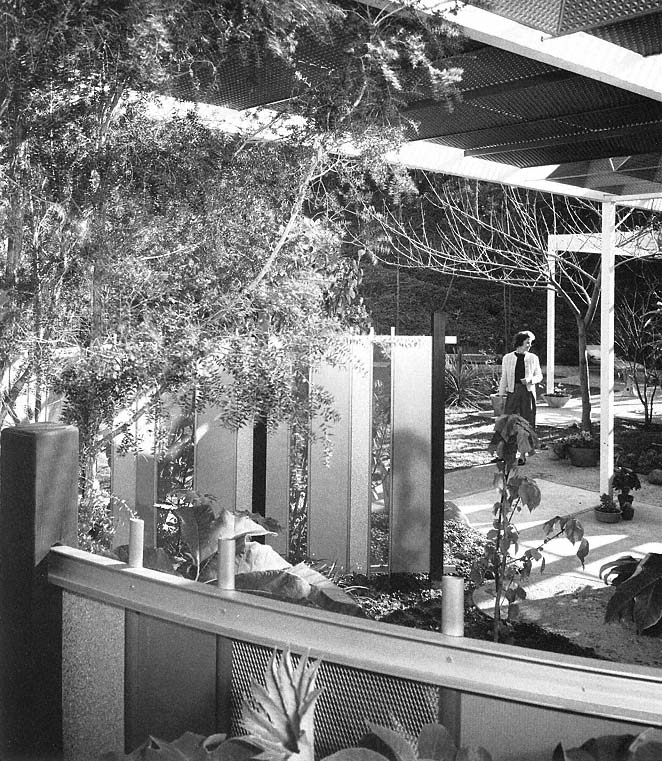

ALCOA Forecast Garden. View north, toward house.

Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, 1959.

[Julius Shulman ]

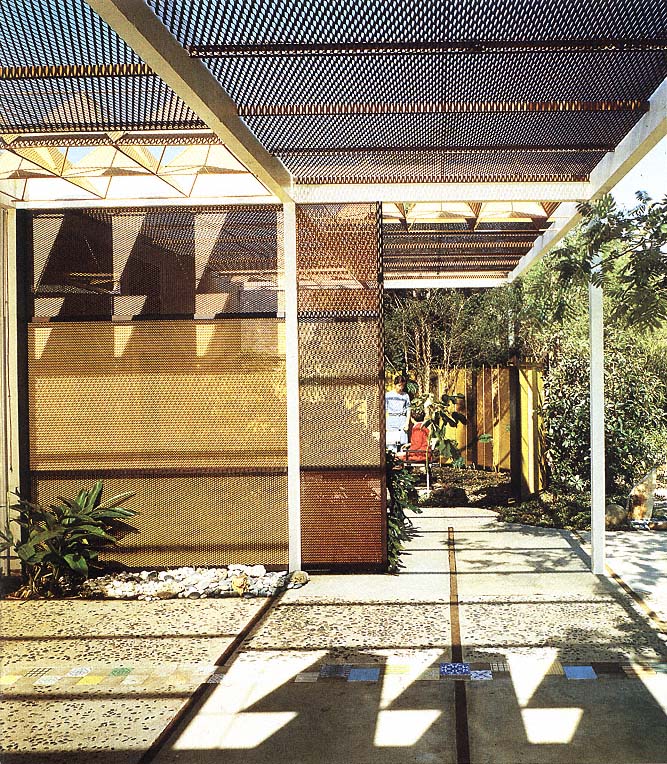

XIV

ALCOA Forecast Garden. Aluminum screen walls and trellis. Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, 1959.

[Julius Shulman ]

XV

Wohlstetter garden. Pool and screen wall. Laurel Canyon,

Los Angeles, mid-1950s. Joseph van der Kar, architect.

[Garrett Eckbo ]

XVI

McCormick pool. Los Angeles, 1950s.

[Garrett Eckbo ]

XVII

Cooper garden. Bel Air, 1961.

[Garrett Eckbo ]

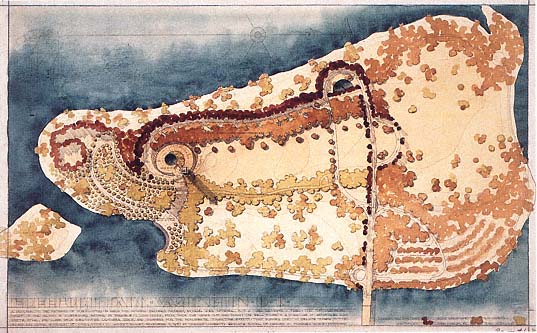

76

Eckbo garden. Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, undated, circa 1954. This unrealized scheme, which included an

elliptical grassed bed, utilized many of the landscape architect's signature elements. Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

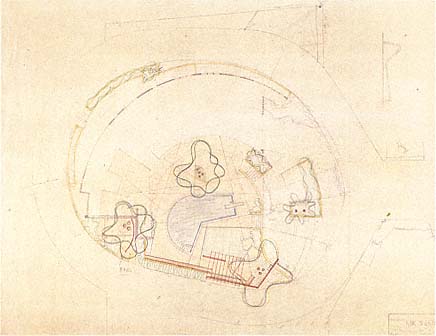

77

ALCOA Forecast Garden. Final site plan. Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, 1959.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

contacted Eckbo about the possibility of having him incorporate significant amounts of aluminum in a garden.[99] He agreed to create a metallic garden in his own backyard. The final site plan (construction drawing dated 5 May 1957, but including revisions until 10 March 1959) positioned various screens and their support structures around a broad circle, recalling the suprematist compositions of Kasimir Malevich [figures 77–79]. A smaller circular pad in concrete already existed, used as a patio area outside the studio. A fountain anchored the northeastern edge of the garden design, spilling into a pool whose shape interrupted the purity of the circle. The garden plan in itself was unremarkable, especially when compared to Eckbo's exuberant schemes, from the years on either side of 1950. More remarkable were the materials with which the project was realized [figure 80].

Materials had always been a major consideration in Eckbo's thinking. From the FSA and war housing projects, he had developed a respect for everyday materials. No material was ignoble in itself; the question was how it was used. During the war years, aluminum's widespread application in aviation brought the metal to popular consciousness. Aluminum became the most modern of modern building materials, sold as sheets, beams, and rods to a public anxious to do-it-yourself. Gasoline companies offered aluminum goblets in brilliant or champagne tints with any fill-up. The metal was easy to work, lightweight, and didn't rust. And the reduction in the output of the defense industries challenged manufacturers to invent peacetime applications for their products and production lines. Presumably with hopes of promoting aluminum as an ideal exterior material, ALCOA sponsored the Eckbo garden as a forecast of what might become the domestic landscape of the future.[100]

While no early correspondence remains in the Eckbo office files, the record of a retainer paid in November 1956 testifies to the company's interest in the project. Eckbo's ostensible client was an advertising agency in Pennsylvania—Ketchum, MacLeod and Grove—which acted as the liaison for ALCOA . Although the contractual agreement was finalized years after the project was under way (4 March 1959), its contents clearly revealed the purpose for which the garden was intended: it was a "Display." The research for, and design of, the gar-

78

Kasimir Malevich. Suprematist Composition , 1916–17.

[© 1996 Museum of Modern Art, New York ]

79

ALCOA Forecast Garden. Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, 1959.

Aerial sketch view of the garden.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

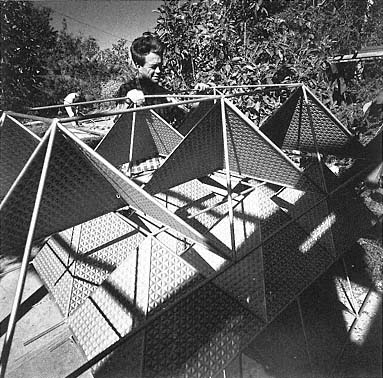

80

ALCOA Forecast Garden. Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, 1959.

Garrett Eckbo examining the aluminum pyramids for the trellis.

[Julius Shulman ]

81

ALCOA Forecast Garden. Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, 1959. Trellis and pyramid outside the studio.

[Julius Shulman ]

den was left within the landscape architect's province. For four months from the announcement of the garden by ALCOA ("April 1960?" is handwritten in the margin), ALCOA was permitted unrestricted use of any of the elements for advertising or merchandising, although the copyright for the design would remain with Garrett Eckbo. From four months to five years, ALCOA retained the right to produce any of the elements of the design, with royalties paid to the designer. Of course, access would be available for ALCOA employees for photography or filming (a promotional film was made). And finally, everything of aluminum had to be made from ALCOA aluminum, a not unreasonable request all things considered.[101]

As described in the ALCOA promotional brochure, aluminum was used in five ways:

1. A sunbreak that acts as an extension of the living room .

2. A one-way screen that affords a view of the planting from the living room, but blocks the view from the studio into the living room and terrace .

3. A curved decorative screen designed to demonstrate the possibilities of enclosure .

4. A free-standing pavilion shelter, providing a retreat from the main garden area .

5. An abstract flower-form fountain that serves as a focal point for the entire group .

Aluminum, as Eckbo realized, was a nearly ideal product. It was light-weight, soft and easily worked, rustproof and noncorrosive when anodized, particularly in its use as shelter and screening. "One can use a plant or a tree," he said, "or an analogous manufactured device. It is hard to do with wood. It is possible to do it, and do it well, with textiles—but textiles are not durable. For light diffusion, expanded metals are excellent, and no other has the qualities of aluminum."[102] Aluminum colors ranged from garish golds to elegant silvers to muted champagnes. The metal's single disadvantage was its ability to conduct heat, a property not beneficial for the growth of plants on trellis surfaces.

Aluminum appeared in the garden principally as a sheet material, most often as expanded mesh. Used both horizontally and vertically it enclosed spaces, provided shade, and overhead formed vaults and pyramids [figures 81, 82; see plate XIV]. Eckbo's curious fountain design, based on a geometrized flower with water spouts as its stamens, was constructed of quarter-inch aluminum plate, crimped, welded, and in places, anodized pale metallic green [see plate XIII]. Aluminum was not used for structural elements, however; wood provided the principal means of support for walls and trellises, as it had traditionally. Wooden frames enclosed the expanded mesh, softening the overall image of the aluminum surfaces, and to some degree naturalizing the manufactured product.

The garden was a publicity triumph and it enjoyed widespread publication in professional, trade, and popular journals and newspapers. While most of the articles drew heavily upon the ALCOA brochure and press release, each biased its reading of the garden according to its audience. "Aluminum invades the garden," shouted Modern Metals; House and Garden called it "the shape of shade to come," and saw the design as an escape from a sizzling sun: "You may well be following [Eckbo's] lead yourself in the not too distant summer: first, because the problem of too much sun is one that has plagued a great many home owners besides Mr. Eckbo; second, because the aluminum components that he has adapted to provide shade on his own living patio are standard structural fabrications." If the publication in 1950 of Landscape for Living had given Garrett Eckbo national and international prominence within the design professions, the completion of the ALCOA Forecast Garden and its attendant publicity in print and on television brought him widespread popular notoriety.[103]

By 1960 the Eckbo, Royston and Williams partnership no longer existed; the firm was reconstituted as Eckbo, Dean and Williams in 1958.[104] Its arena had become far broader than the individual garden. It planned university campuses, converted streets to pedestrian malls, designed public parks, and studied the policy for open space in all of California. The scope of Eckbo, Dean and Williams' work was constantly increasing, the amount of detailed design necessarily reduced.

82

ALCOA Forecast Garden. Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, 1959.

Enclosed patio outside the studio, with pyramidal elements above.

[Julius Shulman ]

The almost manic approach to space and form found in the postwar gardens would never be matched in later designs.

Two decades later, in an interview with Michael Laurie, Eckbo reflected on the importance of garden design in landscape practice:

There's a snobbery in the profession about gardens as being too small and too inconsequential, but I think that garden design is the real grassroots of landscape design. You encounter all the problems of relations between people and outdoor environment in a concentrated and personal way which brings out all the potentials for very special and forceful kinds of design. . . . Private garden work is really the only way to find out about relations between people and environment .[105]

In the hundreds of gardens that Garrett Eckbo designed between 1939 and 1959, he had seriously challenged the historical canon of the garden. He did not work in isolation, and his efforts were paralleled by quality and innovative work by landscape architects such as Robert Royston, Lawrence Halprin, Douglas Baylis, Ted Osmundson, and even—if not as continuously—Thomas Church (ten years Eckbo's senior). As a body of work rooted in the residential garden, however, the designs by Eckbo stand alone in number and aesthetic contribution. Certainly, the various configurations of his practice involved far more than residential designs—it encompassed work for community plans, road layouts, parks, shopping centers, schools and colleges, and churches—but the garden has remained at the heart of Eckbo's contribution. By utilizing a contemporary vocabulary drawn from the arts of painting and sculpture, Garrett Eckbo was able to forge spaces and forms that viewers read immediately as modern.

There was a weakness to this approach, however, and Lawrence Halprin has wisely noted the danger in designs that so seriously applied forefront ideas in painting and sculpture to landscape architecture. Halprin cited the Brazilian painter and garden designer Roberto Burle Marx, and his uncanny ability to transfer a pattern to a landscape and have it seem right—although the particular biomorphic shape does not derive from the lay of the land. "In his brilliant hand, the interlocking forms and swirling patterns produced great painterly gardens. In lesser hands," Halprin chided, "his influence,

in America and elsewhere for that matter, has resulted in superficially decorative and overly complex parterres with very little organic relation to the landscape or relation to the functioning use of the landscape."[106] The avoidance of applying pattern alone, the transformation of dynamic shapes into dynamic spaces—while maintaining rigorous formal investigation—is another mark of Eckbo's success.