4—

Economic Development

With the exception of the foodgathering Chenchus, all the tribal populations of Andhra Pradesh are traditionally subsistence farmers. As long as they lived in their ancestral habitat, protected from the outside world by hills and forests, they produced food grains and reared animals almost exclusively for their own consumption. Contacts with the market economy of more advanced populations were few and of limited importance, consisting mainly of the barter of some items of agricultural or forest produce for supplies of the few necessities, such as salt and iron, which they were incapable of producing with the resources of their own environment. Small groups of artisans, living in symbiosis with the aboriginal farmers, provided them with such items as pots, metal implements, and certain ornaments, but the relations between cultivators and craftsmen were basically also on an exchange basis, and their mutual interdependence operated outside the market economy of neighbouring more advanced areas.

Among shifting-cultivators such as Konda Reddis and Kolams an undiluted system of subsistence farming could be observed as late as the 1940s, and in some remote pockets of primitivity it persists to this day. More advanced ethnic groups, such as Gonds and the majority of Koyas, had then already emerged from total self-sufficiency, but even they consumed most of the grain which they produced, and their need of commodities which had to be purchased with money was very limited. Change came to them in the first decades of the twentieth century, when outsiders acting as agents of the wider money economy penetrated into tribal regions, and governments with their

systems of taxes payable in money compelled the tribals to acquire at least some small amounts of the official currency. Self-sufficiency came to an end, and tribal communities were sucked into a cash economy which had its roots in materially advanced and socially complex spheres outside the tribal regions.

Even in the 1940s there were still many tribals who had only a vague idea of the units of currency, and who easily fell victim to any unscrupulous outsider trading on their ignorance and trustfulness. A phenomenon which today is the bane of many a tribal society, namely that of indebtedness, arose only with the incorporation of the tribal economy within the money economy of neighbouring advanced populations. The primitive subsistence farmer had lacked the means of drawing on outside resources to tide him over a crisis, such as crop failure, or to acquire goods of a value exceeding that of his accumulated resources. The Konda Reddis in remote hill settlements, for instance, did not borrow money or grain if their crops failed to last them for the whole year, but eked out their food supplies by gathering wild tubers, roots, and forest plants.

Gonds and Kolams

At the same time, the Gonds of the Adilabad highlands had already become used to meeting a shortage of their food grain by borrowing from merchants and moneylenders dwelling on the periphery of the tribal area. Thus had started the vicious circle of repaying borrowed grain by delivering to the creditor one and a half times the borrowed quantity as soon as the next harvest was reaped. Unless that harvest was exceptionally good the repayments usually resulted in the recurrence of the need to borrow grain for consumption later in the year.

Yet not all Gonds were compelled to depend on merchants to tide them over lean periods, and many reaped sufficient grain crops, mainly millets, to meet their domestic needs throughout the year. Food grain was then rarely sold, and cash requirements, such as the money needed for paying land revenue or buying clothes, were met by the sale of cash crops, usually grown only in small quantities. Oilseeds and castor were the main cash crops, for the large-scale growing of cotton is a relatively recent phenomenon. In Gond myths and epics there is no mention of cotton, whereas millet and rice both figure prominently.

A fundamental change in the agricultural pattern of the Gonds occurred in the first half of the twentieth century. Until then the Gonds had mainly cultivated the light, reddish soils on the high plateaux and gentle slopes on which they grew monsoon crops during the so-called

kharif season. As these soils could not be cultivated year after year, periods of fallow had to alternate with the periods of cultivation. So long as there was ample land available, this system of frequent fallows allowed the Gonds to grow adequate crops on light soils, and to leave the heavy, black soils in the wooded valley bottoms largely uncultivated. Some farmers, however, used stretches of black soil for growing rain-fed rice during the monsoon and wheat, sorghum, and pulses in the post-monsoon season known as rabi .

The reservation of forests and the shrinkage of the tribals' habitat caused by the incursions of non-tribal settlers compelled most of the Gonds to abandon the practice of frequent fallows and to take more and more of the heavy, black soils under cultivation. Shortage of land and the official policy of granting to individuals patta rights to clearly delimited plots of land, in the choice of which they often had no decisive say, led, moreover, to changes in cropping patterns and to the diversification of the economy of Gond farmers. The man whose patta land consists mainly of light, reddish soil has no other choice than to depend mainly on kharif crops, whereas the owner of heavy, black soils must inevitably concentrate on rabi crops. There are, of course, landowners whose holdings include both red and black soil, but few have sufficient land to permit them to continue the traditional practice of interspersing periods of tillage with extended periods of fallow.

Another change in the farming economy of the Gonds was caused by the allocation of individual holdings to the adult sons of farmers who had previously cultivated a large area with all the resources of manpower available in a joint family consisting of several married couples. Such farmers had been able to cultivate with as many as six or seven ploughs, and this had enabled them to spread their agricultural operations both spatially and chronologically, and to grow a variety of crops on their extensive holdings. Individual farmers cultivating about ten to fifteen acres are marginally less efficient, mainly because they cannot afford to take risks but must concentrate on the cultivation of the food crops on which they depend for their domestic consumption.

Yet another change occurred some ten to twenty years after the allocation of land on permanent patta to individual householders. This change was triggered by the establishment of commercial centres in the heart of the tribal area. Wherever non-tribals engaged in trade and moneylending settled, a cash-oriented economy was brought right to the door-step of many Gonds. The availability of novel commodities displayed in the newly established shops created among the tribals a craving for such goods. The only way of satisfying this craving was the production of crops of a high cash value.

Within the span of a few years, the entire cropping pattern of Utnur

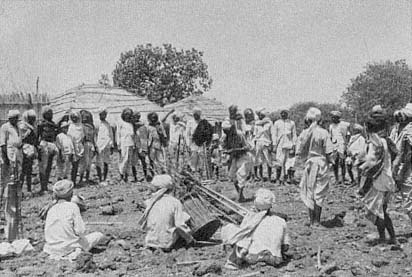

Gond village in the Adilabad highlands: the houses built of wood and bamboo

are thatched with grass; free-standing cylindrical grain bins are made of wattle

and covered with a mixture of mud and cow dung.

Taluk underwent a dramatic change. High prices paid for cotton and the possibility of speedily moving large quantities of this crop by lorry to the cotton market and rail-head at Adilabad transformed a food-producing area into a region concentrating on the growing of cotton. The availability of this valuable commodity brought increasing numbers of merchants, some from states as distant as Gujarat, to a region which twenty years earlier had been a tribal backwater.

One of the new commercial centres owing its rapid growth to the cotton boom is Jainur on the Utnur-Asifabad road. Until 1944 this locality was a deserted site in the midst of forest, and was then resettled by a few Gond families, who had moved there from such nearby villages as Marlavai and Ragapur. Within the past ten years it has turned into a flourishing market centre inhabited by numerous Hindu and Muslim merchants.

In the cotton-picking season in 1979–80, six trucks, each carrying one hundred quintals of cotton, left Jainur daily for Adilabad, and earlier in the year each of the six major cotton merchants had brought ten to twelve truck-loads of sorghum from outside the taluk for the purpose of giving advances of grain to the tribal cotton-growers. As a result of the good harvest, the price of cotton had dropped from the

Circle of Gond worshippers during the annual rites in honour of their clan god,

symbolized by a black yak's tail erected on a stave in the centre of the circle.

previous year's rate of Rs 450–500 per quintal to only Rs 330–50.

The merchants dealing in cotton were the same shopkeepers who supplied the Gonds throughout the year with sundry commodities, and their methods of trading deprived the tribals of the full profits from the change-over to cotton. For cotton brought to Jainur in cartloads, they gave the current price of Rs 330–50. Yet they did not pay cash on the spot, but gave the Gonds receipts and the promise to pay in two or three weeks' time after selling the cotton at Adilabad. Often they procrastinated the cash payment and tried to persuade the Gonds to accept part-payment in cloth or other consumer goods, and for these they asked prices much higher than those current in such towns as Adilabad or Mancherial. Those Gonds who had taken advances of grain, moreover, never received the entire cash value of their cotton when they delivered their crop. An even less favourable treatment had to be accepted by the numerous Gonds who had only small quantities to sell and brought the cotton by head-loads. Such loose cotton fetches a much lower price, which in 1979–80 was about Rs. 2.40 per kilogram, corresponding to a price of Rs 240 per quintal.

The replacement of food crops by cotton affects most parts of Utnur Taluk, and this is reflected in the very substantial imports of sorghum into an area which not long ago was self-sufficient in grain. Thus in

Gond woman of the Adilabad highlands; her forehead is tattooed,

and suspended from a solid silver necklace is a bundle of keys.

Gond wives have the keys to the store boxes and grain chests of the household,

and carry them always on their persons.

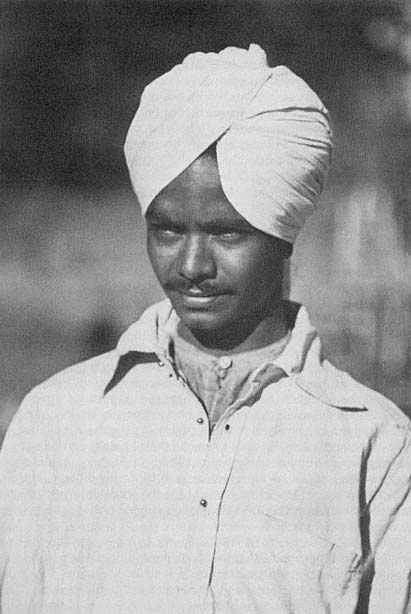

Gond of the village of Marlavai in Utnur Taluk; a white or red turban is the

traditional head-gear, but tailored cotton shirts, now universally worn, are

a modern innovation.

1979 in Narnur, another cotton market, alone two merchants between them brought 1,700 truck-loads of sorghum to their go-downs and from this stock supplied their Gond clients with the grain the Gonds now require because of their shift to the growing of cash crops.

The rapid change in the whole character of the agricultural economy has by no means brought only benefits to the Gonds. While those who possess ample land with heavy, black soil are likely to profit from devoting a large proportion of their holding to the raising of cotton, some Gonds owning only land of lighter soil are also tempted to grow cotton but may reap only a meagre crop. By growing the traditional food crops they would probably fare better. The cultivation of food crops, such as sorghum, also has the advantage that Gonds can estimate their domestic needs and if at all possible keep a store of sorghum to last them throughout the year. The cash obtained from the sale of cotton, on the other hand, is seldom spent for the purchase of a year's supply of grain but may partly be used up in buying luxuries previously beyond the reach of Gonds. After an exceptionally good harvest, there may be no harm in spending part of the cash received for cotton on items other than food grain, but in average and below-average years most Gonds just cannot afford to buy much more than essential clothes and food stuff sufficient to augment their own production of grain and pulses if this is inadequate to feed their families throughout the year.

The easy availability of such commodities as sugar, tea, cigarettes, and spirits in shops within walking distance of many villages, or even in small shops inside tribal villages, acts as a continuous temptation. While a generation ago tea and sugar were luxuries reserved for special occasions, many Gond families nowadays regularly purchase tea and sugar, and men who used to smoke their home-grown tobacco in leaf pipes now buy bidi or cigarettes. Wealthy men even own bicycles, and transistor radios are found in many of the larger villages. The cost of batteries alone for such radios and for the commonly used electric torches is a drain on a Gond's budget justifiable only in years when cash crops yield a good harvest.

The family budgets for 1976–77 set out in my book The Gonds of Andhra Pradesh (pp. 417–21) show that a wealthy man, such as Kanaka Hanu of Marlavai, had a cash expenditure of Rs 3,676, which included payments for land revenue and taxes, fertilizers, and wages for daily labourers. After the very bad harvest of 1978–79, only Kanaka Hanu and four other men of Marlavai expected to be able to balance their budgets, while all the other villagers foresaw that they would have to take loans of grain to meet their domestic needs until the next harvest. Kanaka Hanu was in a relatively favourable position because his holding contains several fields of heavy, black soil on which he grew ade-

quate crops of cotton and wheat, whereas those villagers whose land was of lighter soils saw both their food crops and their cotton crop fail.

In the following year there were good crops, and Kanaka Hanu reaped in kharif twenty quintals of rice, ten quintals of sorghum, two quintals of black gram, half a quintal of maize, half a quintal of oilseed, and twenty-five quintals of cotton. In January 1980 the rabi crops looked promising, too, and Hanu expected a yield of about thirty to forty quintals of sorghum and thirty quintals of wheat. As his domestic requirements of cereals were about fifteen quintals, he had a surplus of grain and could use the income from the sale of cotton—about Rs 8,250—to meet all his cash requirements. Hanu's land-holding, as well as his skill in managing the farm work, are exceptional, and the majority of Gonds have no surplus even in a good year.

A budget representative of a Gond of much more modest means is that of Kodapa Jeitu of Marlavai. Jeitu owns five acres in Marlavai and twelve acres in Jainur, which his brother cultivates on share. Jeitu cultivates with two ploughs; he owns one pair of bullocks and hires another from his brother Kasi, who lives in Jainur.

In 1976–77, he reaped the following crops:

|

His share of the field cultivated by his brother amounted to two quintals of cotton.

The sorghum lasted his family of seven heads for 11 months and the rice for 10 1/2 months. He sold castor at a rate of Rs 250 per quintal, and cotton for Rs 450 per quintal. He spent Rs 440 on clothes, Rs 250 on oil and spices, and Rs 240 on tea and sugar.

He took a loan of Rs 400 from a cooperative society, and he did not employ farm servants.

Tumram Lingu, one of the wealthiest and oldest men of Marlavai, who died in 1978, had owned nineteen acres of patta land in Marlavai and ten acres in Ragapur. His two married sons and one married daughter, deserted by her lamsare -husband, had lived in his house and cultivated with him. He had owned eight bullocks, eighteen cows, and four buffaloes.

In 1976–77, Tumram Lingu reaped the following kharif crops.

|

His rabi crops amounted to:

|

In Tumram Lingu's household there were then six adults and four children, and there was hence a surplus of grain over the family's needs. Gonds reckon that 1 1/4 quintals (i.e. 125 kilograms) of grain is sufficient to meet the average annual needs of one person.

The budgets of Kolams in possession of land are not different from those of Gonds, but there are relatively few Kolams who own economic holdings. One of these is Kodapa Jeitu of Muluguda (near Kanchanpalli), who owns twelve acres and cultivates with two ploughs. There are six persons in his household, including children.

In 1976–77, he reaped the following crops:

|

The domestic consumption of grain was ten quintals, i.e. the grain crop reaped, and the sale of cotton (Rs 1,200) and castor (Rs 125) more than covered the household's cash needs. Rs 700 had been spent on clothes, Rs 300 on oil, salt, spices, tea, sugar, etc., and Rs 31 on land revenue and tax on cash crops.

Besides those Gonds and Kolams who can balance their budget or even have a surplus, there are many who are seldom free of debt because their production of grain does not meet the family's consumption. Kanaka Dhami, a Gond of Kanchanpalli, for instance, was frequently in trouble. In the year 1975–76 he had to borrow from a merchant 2 1/2 quintals of rice. In 1976–77, his harvest was again inadequate, mainly because he had been ill and had hence delayed the sowing of the rabi crops, which consequently failed.

In the kharif season he reaped:

|

His cotton had failed completely and he had sown no other cash crop. The normal grain consumption of the household of six adults and children was ten quintals, and the shortfall was made up by earnings from casual labour. As Dhami had only one bullock he had hired one, and for this he had to pay sixty kilograms of sorghum as rent. But he had still to repay the previous year's loan of rice, and as he had no rice to give, his merchant demanded Rs 320 in cash. To raise this money he sold his only bullock for Rs 600. With the remaining money he bought a young untrained bullock for Rs 150.

The chances of a man like Dhami to free himself from indebtedness are slim, because after repaying the previous year's debt he has probably to borrow again to meet his family's needs for food and essential clothes.

No recent statistics regarding the incomes of Gond cultivators are available, but a study of seventy-four agriculturists in four sample villages of Utnur Taluk was undertaken in 1972 by D. R. Pratap,[1] and if we allow for inflation the findings retain some relevance. The average holding of the families investigated was 13.26 acres, and the cash incomes of the seventy-four agriculturists of the sample were as follows:

|

Attached labourers (farm servants) were paid an annual wage of Rs 400 plus five quintals of sorghum in the villages of Mutnur and Indraveli, and Rs 250 plus six quintals of sorghum in Lakkaram and Jainur.

Most agricultural labourers, who worked free-lance, had incomes between Rs 600 and Rs 1,400 per annum.

The average family income from all sources was calculated to be Rs 2,036.96, and the average per capita income was Rs 209.90, which compared unfavourably with the Andhra Pradesh average of Rs 545.29 in 1970-71.

The low incomes were explained by an analysis of the yield of the fields belonging to a random sample of Gond cultivators. The average yield of an acre under sorghum was 1.41 quintals, the yield of rice per acre was 2.36 quintals, and the average yield of cotton approximately 72 kilograms. Most Gonds do not have the capital to increase the yield of their land by applying chemical fertilizers and sowing improved hybrid seed. Hence agricultural production remains poor notwith-

[1] Occupational Pattern and Development Priorities among Raj Gonds of Adilabad District.

standing various development programmes, which have either remained on paper or been channelled mainly to the non-tribal inhabitants of the project area because these had greater pull with the officials responsible for the distribution of benefits.

We have seen that Gonds have become used to purchasing a number of consumer goods in shops or markets, and this may give the impression that their standard of living has risen in the past thirty years. This impression is partly deceptive, however, for the parents of the present generation had similar resources but spent them in different ways. While they bought few items of outside manufacture and no Gond would have aspired to owning such a thing as a bicycle, they were more lavish in entertaining and in the celebration of festivals and rites. The expenditure of food stuff on weddings and funerals was far greater than it is today, and the occasions for the employment of Pardhan bards were more numerous. Moreover, the rewards these artists received for their performances were much more generous than they are nowadays. The very fact that on many ritual occasions cows or bulls were slaughtered to provide meat for the entertainment of the participants indicates a different type of consumption, and the present addition of tea and sugar to the Gond diet must be weighed against the diminishment of the protein content by the exclusion of beef. This change also has a social aspect. Whereas the slaughter of a bullock provided meat for a large gathering drawn from several villages, a goat substituted as sacrificial animal can feed only a small circle of relatives and close friends.

A change-over to different but not necessarily more valuable items purchased by affluent Gonds is not an indication of a rise in living standards either. Previously Gonds would buy their wives and daughters heavy silver ornaments fashioned by local craftsmen, and many wealthy men wore embossed silver belts. Such items were not necessarily luxuries, because silver jewelry retained its value and in a crisis could be used as security for a loan from a moneylender. Today Gonds with cash to spare buy such articles as wrist-watches, electric torches, or the like, or they spend their money on pilgrimages to Tirupati, an unheard-of adventure thirty years ago. While some gonds now possess bicycles, men of the previous generation often owned ponies which they used exclusively for riding. These examples show that the change in the consumption pattern does not necessarily amount to a substantial rise in the standard of living.

A development which has caused a decline in living standards for a substantial percentage of Gond families is the loss of land to non-tribal settlers. In the 1940s, the great majority of Gonds were independent farmers, whether they held their land on patta or not, whereas today many have no land and no possibility of cultivating government land

on temporary tenure. Their only way of maintaining themselves is to work as farm servants or casual labourers on the land of non-tribal settlers who have displaced the original tribal population. This is a phenomenon not peculiar to Adilabad District or even to Andhra Pradesh alone, but is found in many parts of India. Thus a comparison of the data contained in the census reports of 1961 and 1971 shows that during the relevant decade the percentage of independent tribal cultivators fell from 68 percent to 57.56 percent, while the number of agricultural labourers went up from 28 percent to 33 percent largely, no doubt, owing to the mounting land alienation and eviction of tribals from their land.

It is obvious that the economic position of an agricultural labourer is greatly inferior to that of an independent cultivator, and that even Gonds who in the 1940s did not own land but cultivated government land on siwa-i-jamabandi tenure were far better off than agricultural labourers are today. Those landless Gonds who live in a purely tribal village and work for Gond landowners enjoy at least a social status not fundamentally different from that of other villagers, but Gonds working for non-tribal employers in villages where there are only a few other Gonds are among the most underprivileged tribals and in fact are no better off than Harijans.

The situation of the Gonds, Kolams, and Naikpods in Adilabad District, particularly in Utnur, has all the elements of a collective tragedy. Just at the time when the demand for cotton and the phenomenal rise in its price could have ushered in a period of mounting prosperity throughout the region of heavy, black soil which was so recently in tribal hands, the invasion of outsiders and a change in the political climate have shattered all hopes that the tribals would reap the benefit from their transition to cash crops. The transformation of a sorghum-, wheat-, and rice-growing area into an almost continuous expanse of cotton fields has brought about so rapid a commercialization of the whole economy that the conservative and largely illiterate Gonds cannot keep pace with the change-over to an entirely new system.

The very fact that land uniquely suitable for the growing of cotton is a magnet for advanced cultivators as well as merchants of all types makes it virtually impossible for tribals to remain in control of the land and its produce. Apart from the alienation of land discussed in chapter 2, there is also the penetration of the agents of commercial interests into the remotest villages. Traders who have their open shops and purchasing depots in such places as Jainur or Narnur have a network of agents, usually members of their own family, settled in many tribal villages. These agents keep small shops in which they stock matches, bidi , soap, tea, salt, and similar basic commodities, but each of them also gives advances for deliveries of cotton and castor, and in

this way secures for his principal the crops grown by the villagers, often well below the market price. Such petty shopkeepers also encourage barter transactions such as the exchange of cotton for groundnuts. In March 1979, when the Gonds were short of food after an unusually bad harvest, traders gave one kilogram of groundnuts for one kilogram of cotton, thereby obtaining cotton for about half the price current in Adilabad. The victims of such tricks were naturally not the substantial cotton growers who had several quintals to sell and found it worth their while to take their crop to Jainur or Adilabad, but the small Gond farmers, who had reaped perhaps only twenty or thirty kilograms of cotton and were easily duped to dispose of this as close to their homes as possible.

In Jainur, where a ginning mill has recently been installed, there are at the time of the cotton harvest huge mountains of the precious crop. Truck after truck, loaded with cotton, leaves for Adilabad. Here big business has gained a foothold in what only fifteen years ago was a purely tribal and economically backward area. Insofar as business acumen is concerned most Gonds and virtually all Kolams have remained "backward," and they are not yet capable of taking advantage of the possibilities which the cotton boom has brought to the area. Profits are largely mopped up by the middlemen and by traders to whom many Gonds have mortgaged their crops long before the cotton is even picked.

The unequitable division of profits can be gauged by the contrast between the life-style of the non-tribal businessmen settled in Utnur, Jainur, Narnur, and Indraveli and that of the average Gond villager. The former live in houses built of bricks and cement, fitted with electric lights and fans, own motor vehicles, and are at home in the district headquarters as well as in Hyderabad, while the Gonds continue to live in thatched huts with mud-plastered wattle walls and to wear simple clothes not very different from those their parents used to don.

The affluence of the merchants of Jainur becomes explicable if we compare the prices they charge tribals for their wares with those current in the market towns of other parts of the district. In the following list of prices in Jainur in January 1980, the prices for items of similar quality current in Chennur are given in parentheses:

|

The willingness of the Gonds to pay these excessive prices is sur-

prising considering the fact that a cheap bus ride would take them to places where they could make their purchases at much more reasonable rates. It can only be explained by their relative unfamiliarity with money transactions, which places the greater number of tribals at a disadvantage in their dealings with shrewd members of traditional trading castes.

The phenomenon of the growing exploitation of the tribal farmers by a class of immigrant nouveaux riches abetted in their domination of the local population by venal or lethargic petty officials is not peculiar to Adilabad. Similar situations have been observed in many areas and over long periods, and in some regions, such as Srikakulam District, violent reactions occurred when the long-suffering tribal peasantry saw their salvation in political movements led by Naxalite extremists. A gradually widening gap between the rich and the rural poor has been demonstrated by many investigations based on official All-India statistics which show that the percentage of rural households living below the extreme poverty line rose from 38 percent in 1960 to 53 percent in 1968.

The impossibility of ascertaining with any accuracy the extent of the land actively controlled and utilized by traders and moneylenders, even if not owned by them in law, is largely due to the connivance of minor revenue officials in illegal land transactions which make a mockery of the protective legislation to which the government is officially committed. Even visual examination of the undisguised accumulation of wealth by non-tribals in commercial centres such as Indraveli and Jainur and the equally blatant poverty of many a tribal settlement gives the lie to the official assumption that economic growth, even if initially set in motion by non-tribal agents, must ultimately also benefit the tribal populations. In Adilabad most tribals were in 1980 far worse housed than in the 1940s and early 1950s, and their chances of survival as independent cultivators have greatly diminished.

While the decline of the tribal prosperity is hardly surprising in an area exposed to a development by recent settlers which can only be described as "colonial," it is strange that this should have occurred at a time when, at least on paper, the government of Andhra Pradesh had sanctioned very large sums intended exclusively for tribal welfare, and was publicly committed to a policy of protecting the interests of the so-called "weaker sections" of the population.

Koyas

The development of the economy of the Gonds of Adilabad is paralleled by that prevailing among the Koyas of Warangal and

Khammam. In chapter 2 we have seen that in these districts, too, the local tribal population has suffered from the alienation of much of their land by members of immigrant, economically and politically more powerful populations. Within the past forty years many Koyas have been reduced to the position of landless agricultural labourers, and it is only in villages remote from motorable roads that Koyas have retained all of their land and preserved a relatively high economic status. One of the few islands of Koya prosperity, remnants of a former widespread condition, is the village of Madagudem in Narsampet Taluk. There 129 Koya families and a few families of Harijans share 398 acres of cultivated land, 30 acres of which are already irrigated by a newly constructed tank and 100 acres will shortly come under irrigation. Twenty Koya families who came from other localities to join kinsmen settled in Madagudem have no land of their own but cultivate on share with local Koyas who possess land. Half of the produce goes to the owner of the land, and the rest to the sharecropper, provided he cultivates by himself. But if the owner takes part in the cultivation, the yield is divided according to the input of each of the partners. Thus if owner and sharecropper each work with one plough, the owner gets half the produce for his land and one quarter for the labour contributed. In such a case the sharecropper is entitled only to one quarter of the yield. This arrangement is less generous than the system of sharecropping of the Konda Reddis, who divide the produce only on the basis of the number of ploughs contributed by each partner irrespective of the ownership of the land (see the following section of this chapter). Some Koyas of Khammam District follow a similar system. In Ankapallam village, for instance, the owner does not get a share for his land, but if he provides plough bullocks he is given one bag of grain for the bullocks, and the rest of the yield is shared according to each partner's input of labour. The land revenue is shared in any case.

The prosperity of the Koya community of Madagudem, so far unaffected by rapacious outsiders, finds visible expression in the comfortable and spacious homesteads characteristic of this village. In front of each of the well-built houses there is an open structure of the same size as the home itself. Massive teak-wood pillars rise from a raised mud platform, and a thatched roof, as high as that of a dwelling house, provides shelter from rain and scorching sun. In this open hall much of the housework, such as the pounding of grain, can be done in comfort, and hence there is no need for the members of the family to cram into the dark interior of the main house. Many of the villagers have vegetable gardens, often irrigated by wells from which water is drawn in buckets, and here and there are small groves of mango trees. Besides cattle, the Koyas keep pigs, and the headman even owns some

guinea fowls. This idyllic atmosphere of rustic peace and well-being stands in stark contrast to the shabby huts of Koyas crowded together at the outskirts of settlements where non-tribal newcomers have occupied the centre of the village site.

Economic Development among Konda Reddis

In chapters 2 and 3 we have seen that the fortunes of the Konda Reddis in recent decades have been determined largely by two factors: the occupation of land suitable for plough cultivation by non-tribal new-comers and the restriction of shifting cultivation by the Forest Department. Within the limitations set by these two factors, Reddis are adapting themselves in different ways to a situation in which few of them can any longer pursue the life-style natural to their grandparents and parents. No doubt, there are even now isolated communities, each consisting of a small number of families that live in the depth of the forest as yet undisturbed by outsiders or even the control of the Forest Department. One such community I encountered in 1978 in a remote corner of Rekapalli Taluk, to the north of the Godavari River. There six houses then stood in a small clearing surrounded by high trees, but only two of them were inhabited at the time of my visit. A cyclone had done much damage to the sorghum crop, breaking many of the high stalks. The owners of the small cultivated plots had nevertheless saved some of the ears, and these were drying on a small wooden structure. For immediate consumption the men were boiling some wild roots, which had to be soaked in running water for two days before they became edible. Apart from a few cooking vessels, hatchets, bows and arrows, digging sticks, and home-made baskets these Reddis had few possessions, but they seemed cheerful and content because no one disturbed them, and in the forest they found sufficient food to supplement the grain grown on their hill fields. The other inhabitants of the small hamlet had left their houses and moved to temporary huts built on hill slopes among the crops, which had still to be watched.

It is undoubtedly in such an environment that the practice of sharing all land has developed. Where there was no shortage of cultivable hill slopes, the members of a small community considered all the land in the vicinity of their settlement as their joint property, accessible to anyone who wanted to clear a piece of forest. Among the Konda Reddis of the villages on the left bank of the Godavari, communal ownership of the land was practised until some twenty years ago when the leasing of land to non-tribals began and land became a scarce commodity. Yet the principle of sharing whatever land there is left seems

deeply ingrained in Reddi custom. When in villages on both sides of the Godavari title deeds (patta ) to land were somewhat haphazardly granted to Reddis by government officials, it happened that some families were left out. But cooperation between the villagers was so good that those without patta land were nevertheless allowed to share in whatever land was available. When I revisited Kakishnur in 1977, some thirty-seven years after my first fieldwork, I found that several men who had very modest holdings, which they and the members of their family could easily have cultivated by themselves, nevertheless allowed other men to whom they were not bound by kinship ties to cultivate with them as sharecroppers. The yield was divided equally among all workers without an extra share being set aside for the owner of the land. I found an example of similar cooperation in Motagudem, a small Reddi village in the hills of West Godavari District close to Gogulapudi (see chapter 10). There one Reddi, Boli Chinna Gangaya, originally of Gogulapudi, had spontaneously achieved the transition from slash-and-burn cultivation to permanent cultivation with ploughs and bullocks. He owned four bullocks and nine cows, all the off-spring of a calf bartered by his father for a pig. By never selling any cattle he built up this small herd and then cleared some flat land and started ploughing, while all other villagers continued with their digging stick cultivation on podu fields. Another man, who had come from a neighbouring village, joined him in this enterprise, but although the plough bullocks all belonged to Gangaya, who had also made the land arable, the two partners shared the yield equally. Jointly they also cultivated a podu field and divided the crop in the same manner.

A truly cooperative spirit, natural to primitive societies regarding all land as communal property, survives here into an age when governments recognize no other ownership than that of individuals. But where competition for land with non-tribal newcomers increases and land becomes a marketable commodity, the generosity of landowners vis-à-vis indigent co-villagers tends to fade. We have seen that among Koyas of Khammam landowners already charge sharecroppers for the use of their land, and the Gonds of Adilabad have given up the free sharing of land ever since individuals were allotted separate holdings.

Among the Reddis of the Godavari region, agriculture has for some time ceased to be the sole basis of the economy. The reasons for this development are two-fold. The restrictions on slash-and-burn cultivation described in chapter 3 forced the Reddis to seek other sources of subsistence, and the arrival of forest contractors in need of labourers capable of felling and transporting bamboo provided an alternative to the old order. While previously the Reddis had been free to fell the forest for their own purposes, they could now use their skill in wood-

craft and familiarity with the hill forests by working for those who had begun to exploit the forest for commercial use.

In my book The Reddis of the Bison Hills , I discussed in detail the process which had turned many Reddis from self-sufficient cultivators into forest labourers, who often had to neglect their fields because of the demands of their new occupation. A brief recapitulation of the situation as I found it in the early 1940s will therefore suffice in this context.

Judging from local tradition and some remarks of G. F. C. Wakefield, who travelled in the Samasthan of Paloncha in the early decades of the present century,[2] the Reddis of Hyderabad State lived then mainly "in the heart of the jungle in primitive huts. . . . each hut, containing one family only living on the products of the jungle helped out with small patches of cultivation of a giant species of jowari ." This picture drawn by Wakefield applies today only to a very few groups of Reddis, such as those of Kutturgata (see chapter 6), but even in the 1940s most Reddis had abandoned their traditional forest life. With the extension of an effective administration into the hill tracts, the Reddis had become liable to money payments for the use of their land and certain forest products, and in order to meet these obligations, they had to supplement their income by selling their own labour. Contact with lowlanders also instilled in them a taste for previously rare or even unknown commodities, such as spices, more substantial clothes, and metal and glass ornaments. The cash required for the purchase of such goods could be obtained by accepting employment offered by forest contractors who had begun to exploit the rich timber and bamboo growth in the hills flanking the Godavari. Contact with other castes also familiarized the Reddis with the practice of plough cultivation, and in some of the fertile alluvial pockets of the Godavari Valley, they began to plough with bullocks on permanently cultivated fields. Both regular forest labour and plough cultivation fostered a greater stability of settlement, and this led ultimately to the formation of relatively large villages on the banks of the Godavari, whose inhabitants depended only partly on slash-and-burn cultivation and the gathering of wild jungle produce, for they gradually had gotten used to the provisions received from merchants in payment for their labour in the forest.

The transition to an economy largely dependent on wage labour was by no means beneficial, for already in the early 1940s most Reddis of the Godavari zone had become entirely dependent on merchants and enmeshed in a web of indebtedness from which they could not

[2] "Note on a Visit to the Prehistoric Burial-Grounds of Janampett, in the Paloncha Taluka of Warangal District of H.E.H. the Nizam's Dominions."

extricate themselves by their own efforts. In order to drag bamboos to the riverbank, from which they were floated down to the timber market at Rajahmundry, they needed bullocks, and these they obtained mainly on credit. Moreover, merchants provided their labourers with provisions the cost of which was set against wages earned. Payment was by piece-work, and in 1941 merchants were supposed to pay their men Rs 2 for felling one hundred bamboos and transporting them to the riverbank. This worked out at a daily wage of Rs 1/4, corresponding in purchasing power to about three to four kilograms of millet. In practice, however, the merchants paid only a fraction of the fixed rates, and the majority of the Reddis' earnings were withheld on the pretext of old debts and the interest accruing. The merchants took advantage of the Reddis' inability to make any but the simplest calculations or to check on any transaction. To all intents and purposes most Reddi forest labourers were bond-servants entirely at the mercy of their employers. This situation is illustrated by the fact that it was not unusual for a group of Reddis to be "sold" by one contractor to another who then took over their debts.

In several reports to the Nizam's government,[3] I exposed this tyranny of the big timber contractors, and as a result of the action then taken by the administration the power of the principal merchants was curtailed for the time being. A cooperative scheme, first launched by a Swami, resident in a hermitage at Parantapalli, enabled the Reddis of several villages to draw fair wages, and free themselves from the oppression of unscrupulous contractors.

Subsequently the government department concerned with tribal welfare took over the organization of the cooperative exploitation of the forest coups in the Godavari area. A cooperative society located in the riverbank village of Koida took the coups in auction from the Forest Department, and worked them for the sole benefit of the tribesmen, both Reddis and Koyas, who were also supplied with provisions at fair prices. This society operated from 1947 till 1962, and the Reddis of the area are still talking nostalgically of the prosperity and security which they enjoyed while it was functioning. Unfortunately and inexplicably this cooperative venture came to an end when in 1962 the Forest Department leased out all the bamboo coups to the Sirpur Paper Mills at a rate lower than the cooperative society had paid. Inter-departmental frictions and the often demonstrated indifference of the Forest Department to the interests of tribal populations are the probable causes of this development, which destroyed with one stroke all the welfare work done among the local Reddis for several years.

[3] See Tribal Hyderabad , "Notes on the Hill Reddis in the Samasthan of Paloncha," pp. 1–35.

When I visited Koida and other Reddi villages in 1978, conditions had largely reverted to a state of affairs as unfavourable to the Reddis as that which I had observed in the early 1940s. The Reddis were once again under the domination of non-tribal merchants, to whom most of them were indebted. But while in the forties merchants had resided in Rajahmundry and had come to the Reddi area only occasionally during the bamboo-cutting season, many have now built houses in Reddi villages and live there most of the year. In chapter 2 I have already discussed the way in which such merchants have acquired the de facto use of land which still belongs nominally to Reddis. Today they are only indirectly involved in the bamboo-cutting business, but by utilizing much of the village land for the highly profitable cultivation of tobacco and chillies, they force the Reddis to rely for their livelihood mainly on forest labour.

The Sirpur Paper Mills has established an organization with a staff of supervisors and clerks who receive and weigh the bamboos brought by Reddis to the riverbank. The fixed rate according to which the labourers should be paid is seven paisa (i.e. Rs 0.07) per kilogram, but I was told that in practice the labourers receive only six paisa per kilogram. The quantity of bamboos individual labourers, a few of whom are women, can deliver each day varies from 50 to 150 kilograms, and thus the daily earning should be between Rs 3.50 and Rs 10.50, but is in fact considerably less. First, the representatives of the firm pay only at a rate of six paisa per kilogram, and second, they pay the labourers only once a month, or sometimes even only once in two months. Being illiterate the Reddis lose count of their deliveries by the time they are paid, and this enables the clerks to divert some of the wages to their own pockets. If between pay-days the labourers need payment in order to purchase food, the clerks give them slips of paper which some of the local shopkeepers will accept in place of cash. Although there is in Koida a store of the official Girijan Corporation, where the Reddis could obtain grain at cheaper rates, the vouchers issued to the Reddis can be cashed only at shops whose owners are in league with the employees of the Sirpur Paper Mills. Thus the Reddis get in fact much less payment than they should receive according to the fixed rates. Not all Reddis own bullocks, and those who have to hire a pair must give to the owners of the bullocks half of their earnings. It is virtually impossible for a Reddi to purchase a pair of bullocks with borrowed money, for the local merchants exact 50 percent interest per annum.

Bamboo cutting is seasonal work, which continues from mid-September throughout the winter until the beginning of the monsoon in June. Some provident men save cash for the lean months when there is no forest work, whereas others take loans from merchants. In vil-

lages with a large non-tribal population, such as Koida, Reddis have largely lost the habit of gathering wild roots and tubers and borrow grain from shopkeepers when their own store has run out and they have no earnings from wage-labour. In this way they remain indefinitely indebted, and merchants encourage this habit in order to maintain their control over the tribals, whom they require for work in their tobacco and chilli plantations.

In villages where there are few or no non-tribals, Reddis still collect roots for their immediate consumption, and in Kakishnur, where I spent some time in December 1977, I saw every evening groups of women returning from the forest carrying digging sticks and baskets full of edible tubers. But my suggestion to the Reddis of Koida that they might free themselves from indebtedness if they reverted for some time to the eating of jungle roots fell on deaf ears. They said that they had become used to eating rice and had no more taste for their old diet.

Even in Gogulapudi, one of the most conservative villages, which has outwardly changed little since 1941, people rely less than they used to do on jungle produce, and buy some grain with the cash they earn by forest work. There the young headman told me that from October 1978 to January 1979 he had earned Rs 310 by cutting bamboos in the pay of the Forest Department, which in that area did not auction coups but worked them departmentally.

The economy of the Reddis in the high hills of East Godavari District differs from that of the Reddis of Khammam District because of the lesser importance of forest work. There are no bamboo coups leased to contractors, but the Forest Department occasionally employs Reddis for plantation work, and pays daily wages of Rs 5.50 for men, Rs 4–4.50 for women, and Rs 3 for children. Unpaid labour is exacted for the clearing of forest lines.

In this area slash-and-burn cultivation (podu ) is still one of the pillars of the economy, but in recent years many Reddis have in addition developed the cultivation of rice on irrigated fields. Land and climate are also suitable for the cultivation of oranges, and the recent improvement of road communications facilitating the transport of this perishable crop has stimulated the expansion of horticulture. The muttadar of Kakur, Pallala Jiappa Reddi, is a good example of a successful tribal entrepreneur. He lives partly in Kakur and partly in the new block headquarters, Marudimilli, where he stays in his father-in-law's house. In Kakur he owns 300 orange trees, and when the oranges ripen he brings them to Marudimilli and sells them to traders who come with trucks from Rajahmundry. The oranges are sold by numbers at an average price of Rs 100 to Rs 125 per 1,000. In normal years Jiappa Reddi reaps 800–1,000 oranges per tree, and his gross income is

Rs 20,000–25,000. The carriage by head loads to Marudimilli is Rs 2 per 100 oranges. In years when not all trees bear fruit, his net income is about Rs 4,000, but there are also years of complete crop failure. In Kakur every family owns some orange trees, but there are other villages where the number of those owning orange groves is small. Some of the fruit growers transport the oranges to such markets as Marudimilli, while others sell the crop on the trees to traders, but usually only when the fruits have formed.

Most of the traders operating in the area are Valmikis, also known as Konda Mala, a community believed to have originated in the lowlands but settled in the hills for several generations. The symbiosis of Reddis and Valmikis has on the whole been to the latter's advantage, and some Reddis speak nowadays with some scorn of the exploitative practices of their Valmiki neighbours. Previously Valmikis bought up most of the minor forest products collected by Reddis at low prices and resold them at vast profit in distant markets. Similarly they often bought the whole orange crop of a Reddi, paying only a fraction of its value. Valmikis owned ponies and pack bullocks, and could thus transport such goods more easily than Reddis, who would have had to move them by head-loads. Since the construction of motor roads and the establishment of a weekly market at Marudimilli, Reddis are no longer in need of Valmiki middlemen and can sell their produce directly to lowland traders. Yet some exploitation continues, and Valmikis who are averse to manual labour employ Reddis to build their houses, paying them derisory fees, and even get their podu fields cleared by Reddis, whom they often give only one rupee and a midday meal for a day's work. It would seem, however, that this type of collaboration is on the way out and that many Reddis, becoming aware of the changed economic circumstances, are no longer prepared to let themselves be exploited by Valmikis, whom they have always regarded as untouchable and socially inferior notwithstanding their material successes.

Development Projects

Although large amounts of government funds have been spent for tribal welfare, the number of schemes aimed at transforming the economy of tribal communities in a radical way is very small. Such measures as the provision of wells and the distribution of plough bullocks have certainly had beneficial effects, but did not bring about fundamental changes. The cooperative society through which Reddis and Koyas were enabled to exploit the forest wealth of their ancestral environment was one of the few schemes which had achieved such a

change, but we have seen that it was unceremoniously disbanded by the Andhra Pradesh government, probably because at that time the Forest Department preferred to deal with a large organization such as the Sirpur Paper Mills and had no compunction in sacrificing the interests of the Reddi and Koya labourers.

In some cases well-intentioned innovations could not be sustained because the tribals were mentally not adjusted to economic pursuits different from their traditional way of gaining a livelihood. An example for this was the attempt to turn the foodgathering Chenchus into plough-cultivators. In Kurnool District, which in the days of British rule belonged to Madras Presidency, the first efforts in that direction were made in the 1930s, and when I visited the settlements of Peddacheruvu, Bairluti, and Nagerluti in 1940 about 10 to 20 percent of the families living there were cultivating on a small scale. However, on my return visit in 1978 I found that for various reasons, including perhaps the less than helpful attitude of the Forest Department, cultivation by Chenchus of these villages had virtually come to an end. In Peddacheruvu I was told that in 1943 ten men had been supplied with plough bullocks, and that by borrowing these bullocks six more men used to cultivate. But when the bullocks became old or died of disease the Chenchus could not replace them. An old man, who himself had cultivated, explained that those who had bullocks and hence could cultivate never sold grain but distributed any surplus to those villagers who had no cultivation, a practice in accordance with the old Chenchu custom of sharing the meat of any game brought down in the chase. Hence the Chenchus could make no provision for replacing their bullocks by buying calves, and the whole move towards settled cultivation ultimately collapsed. Yet, the Chenchus have not completely given up the idea of growing grain crops, and on small plots near their huts some of the previous cultivators till the land with the help of a light plough drawn by hand. The old man who showed me the use of this plough said that he grew mainly maize and even now distributed part of his meagre crop among his friends. This example shows that it is easier to introduce a new technology than to develop a sense of providence. Whereas even the poorest peasant, rooted in the traditions of an agricultural society, makes every effort to provide for a replacement of the plough cattle so vital for his economic survival, the Chenchu, used to the hand-to-mouth existence of the foodgatherer and hunter, has no such innate care for the morrow, and any scheme aiming at a transformation of his economy would have to extend over a very long period during which sympathetic guidance would have to nurture the growth of a sense of economic realism.

Where the traditional economy has already necessitated long-term planning, as every developed agricultural economy does, it is rela-

tively easy to persuade people to devote their energies to novel projects which require sustained application. An example of such a project is the transition from conventional farming with an emphasis on grain crops to extensive fruit farming. In Chennur Taluk of Adilabad District members of various backward classes have been assisted in the development of mango orchards on a large scale. The beneficiaries are Manevar (a Telugu-speaking Kolam sub-tribe), Bestas (a caste of tribal fishermen), Netakanis (untouchable weavers), Banjaras, and various other members of backward communities. The project owes its inception to a private citizen, namely N. V. Raja Reddi, a prominent landowner and businessman of Bhimaram in Chennur Taluk. In 1971 Raja Reddi distributed a substantial part of his own land to local Manevar, Netakanis, and other landless families, and helped the recipients to plant their plots with mango saplings, which he had obtained from suppliers in the coastal region. Moreover he persuaded the Tribal Welfare Department to sponsor a mango orchard collective farming society located in the village of Dampur. The department provided an initial development grant of Rs 100,000 for a scheme covering 102 acres and benefiting thirty-seven tribals, five Harijans, and six members of backward classes. This grant enabled the newly formed society to purchase 3,080 mango plants, agricultural implements, and bullocks and carts. The latter were allocated to the members of the society so that they could earn cash wages by transporting timber for contractors, and thus make a living during the five years before the mango trees would bear fruit. For three years the young trees had to be laboriously watered by hand, and to facilitate this irrigation wells were dug. While from the fifth year onwards a small cash income was derived from the sale of the first mangoes reaped, a substantial yield occurred only in the seventh year. Similar schemes, partly financed by an agricultural development bank, were started in other villages, and in June 1979 twenty-five more villages were incorporated in the project. Subsequently 70,000 mango saplings, each costing Rs. 5, were planted by 450 farmers. Of these 20,000 were purchased for cash, and 50,000 were bought with the help of bank loans which in the case of tribals were subsidized to the extent of 50 percent by the Integrated Tribal Development Agency. During the first five years of the loans, the borrowers have to pay only the interest, and after that period they have to repay the loans in twelve annual instalments, a condition the farmers can easily comply with once their mango trees bear fruit. The land utilized for the mango groves is almost useless for the cultivation of cereals because of the nature of the top-soil, but mango trees can sink their deep roots to a stratum containing humidity throughout the year.

When I visited the area in January 1979, I spoke to many villagers

participating in the project, and their experiences demonstrated how successful the venture had already proved. In the seventh year after planting the saplings, i.e. when the trees were mature enough to bear substantial quantities of fruit, the farmers had derived profits varying from Rs 500 to about Rs 1,800 per acre, according to the care the trees had been given, the quality of soil, and above all the method of marketing. For some farmers sold the crop to traders for a lump sum before the mangos were properly formed, while others sold the ripe fruits by weight, the latter method proving more profitable.

One Manevar had planted 250 saplings with the help of a loan of Rs 1,000. Of these 220 survived the critical first hot season, and in the fifth year after planting the owner leased the trees to a trader for Rs 930. In the sixth year, which was a bad one, the income was only Rs 350, but in the seventh year, when the trees were approaching maturity and promised a good crop, he accepted an offer of Rs 5,000 for the entire crop even before the mangos had ripened. He told me that in the future he would not lease out the trees for a lump sum paid in advance but would sell the fruit by weight. The joint family of this particular man also owned some paddy land, which yielded enough rice for domestic consumption. Hence the profit of Rs 5,000 did not have to be spent on buying food; part of the money was used to defray marriage expenses, and Rs 700 was spent on installing electricity in the family home.

A Besta owning 145 trees had earned Rs 200 in the fifth year, Rs 250 in the sixth year and Rs 8,300 in the seventh year. In that year he had not leased out the trees but sold the mangos by weight. Rs 8,300 is a fabulous sum for a low-caste villager, but the amount was not frittered away. Rs 2,000 was used to pay off all debts, Rs 2,000 went for hospital expenses after an accident involving the man's old father, Rs 500 was used as part payment for an oil-driven irrigation pump, Rs 500 went for the installation of electricity, and Rs 1,000 was used for the purchase of food grain.

Even more successful was a Harijan of weaver caste who owned 600 mango trees, some of which he had planted as early as 1967, before the beginning of the official scheme. In the tenth year of their life he had earned Rs 10,000, and in the eleventh year the profit was once again Rs 10,000. Most of this money was invested in improvements of his land, such as the construction of an irrigation well at a cost of Rs 7,000. The only luxuries bought were a radio and a watch for his son.

Such successes have acted as a powerful advertisement for the productivity of mango orchards, and many requests for loans and technical advice are being received from villagers in neighbouring areas. At the beginning of the project there was strong opposition from local landowners, who feared that they might lose part of their labour force

if landless tribals and Harijans could be turned into successful fruit farmers. They tried to sabotage the scheme by insidious rumours about the intention of government and the cooperative society, and this propaganda initially led to the wilful destruction of hundreds of saplings, but was ultimately defeated by the obvious success of the venture.

One of the lessons learned from this horticultural enterprise is the urgent need for help and encouragement by leading local personalities in all movements which aim at a radical transformation of the economy in tribal areas. Governments can do much by giving financial aid and technical advice, but in view of the frequent transfers of officials, one of the gravest weaknesses of the present system of administration, only local non-official personalities of imagination and integrity taking an active interest in the development of backward communities can guide a programme of innovation from its inception to its final fruition.

Another pilot scheme for the development of novel cash crops is being conducted in the tribal areas of Vishakapatnam District. There coffee plantations are established by the Girijan Corporation, and during the first five years local tribals are employed as labourers and trainees to learn the care of coffee bushes. After these five years the plantation will be handed over on loan to the same tribals who worked on it as labourers in the expectation that they will be able to manage the coffee cultivation by themselves. The coffee bushes would then have a further life-span of about ten years. The scheme is only in its beginning, and the outcome is hence still uncertain.

A totally different attempt to modernize the tribal economy is at present underway in Srikakulam District. There Jatapus and Saoras have been encouraged to grow sugar-cane, and every cultivator switching to the cultivation of this crop is given a one-time, non-returnable subsidy of Rs 400. Near the village of Rastukunta Bai a modern sugar factory has been built, and 250-300 tribals, both men and women, work in this mill every day in three eight-hour shifts, earning a daily wage of Rs 4. The work suits the Saoras and Jatapus, for it is largely in the open where the cane is being unloaded and cut and in large, airy halls. Expert workers and mechanics are being imported from Uttar Pradesh, but there is a scheme for the training of local tribals. The factory is not yet self-supporting, and depends on government subsidies, but the experiment of furthering the tribals' cultivation of a profitable cash crop and at the same time creating opportunities for industrial work suitable for tribal men and women is certainly worth supporting.

The only other instance in Andhra Pradesh of the employment of numerous members of tribal communities in industry is in Kham-

mam District, where Koyas have been working in the Singareni collieries ever since the beginning of mining operations in the early years of the century, when the first mine was established at Yellandu in the heart of the Koya country. Most of the Koya miners lived in villages close enough to Yellandu to enable the men to walk to work whenever they were free from agricultural activities. Particularly in the months of March, April, May, and the first half of June, the collieries could count on the Koyas from the vicinity, who at times constituted more than 25 percent of the total labour force. However, when the collieries were shifted to Kothagudem some twenty-five miles away the employment of Koyas fell off, for those in the villages near Yellandu could no longer walk daily to the mines, and did not like to stay away from their villages for weeks at a time. Various efforts of colliery officials to persuade experienced labourers to move to Kothagudem and live in labour lines had little success. In the vicinity of Kothagudem there were few large Koya villages, and even from those not many men went to work in the mines. When I investigated the situation in 1943, I found that there were only 497 Koyas among a total labour force of 8,000; about 70 percent were men and 30 percent women. Of these, 384 Koyas, both men and women, worked underground and 113 worked on the surface; 454 were living on company ground, and very few walked to work from villages. At that time the company could have employed 1,500 more Koya labourers, but it seems that no one found a solution to the problem of transport from the villages near Yellandu.

In 1978 I revisited the area of Yellandu, particularly the village of Sudimalla, where in 1945 I had been instrumental in establishing a Koya teacher-training centre similar to the Marlavai centre in Adilabad. Among the people who gathered there were several who are employed by the Singareni collieries. Most of them go to work on bicycles, and there is now also a good bus service. Conditions of work have greatly improved, and men employed permanently receive a monthly salary averaging Rs 400, while those on piece-work can earn even more. Koya supervisors in underground work earned Rs 700-800 per month. Fifteen villages in Yellandu Taluk provided then a labour force of some 400 Koyas, and in some of the mines 75 percent of those employed were Koyas. There was a reversal of the situation on the labour market. While in the 1940s the company sought more Koya workers, being generally short of labour, in 1978 the Koyas I spoke to complained about the difficulty of getting employment in the mines. They were particularly unhappy about the termination of the company's earlier practice of giving priority in recruitment to the sons of retired miners. Now all applications for employment in the mines are

processed by the labour exchange, and Koyas feel that the new system erodes their communities' old connection with the mines.

The same company now also operates mines at Bellampalli in Adilabad District, but there tribals do not constitute a significant proportion of the labour force, as the local Gonds and Kolams have not been able to establish themselves in the industries of that district.

In a national situation of increasing unemployment in many branches of the economy, it is unlikely that in the foreseeable future significant numbers of tribals will be able to earn their livelihood in major industries. It appears, therefore, that concentration on the improvement of tribal agriculture is still the most promising policy for governments and unofficial agencies concerned about the welfare of tribal populations to adopt.