The Living Garden

In 1949 Eckbo wrote: "We must think of plants as an endlessly varying series of living units, each with its specific cultural requirements, and each with its specific qualities resulting from size, rate of growth, silhouette, structural form, texture, color and fragrance." The new approach reified the role of vegetation in the historical garden, it did not refute it. In current practice, wrote Eckbo in 1948, four reasons for choosing plants prevailed: practical planting addressed functional problems such as erosion control; pictorial planting offered vegetation as a visual subject; sentimental planting "include[d] the rock garden,

64

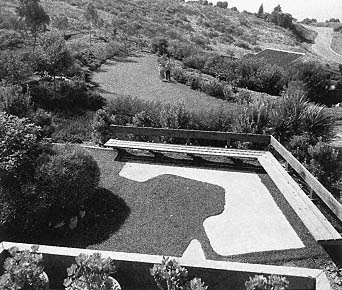

Goldstone garden. Site plan. Beverly Hills, 1948. Once again, the garden's composition recalls

the work of Kandinsky and Moholy-Nagy in its free play of geometric and soft forms. Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

65

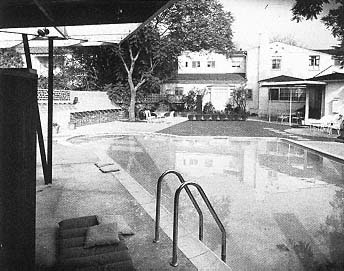

Goldstone garden. Beverly Hills, 1948. The composition joined

pool shape, trellis, and textured wall—the existing house served

as foil.

[Shan Stewart, courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

66

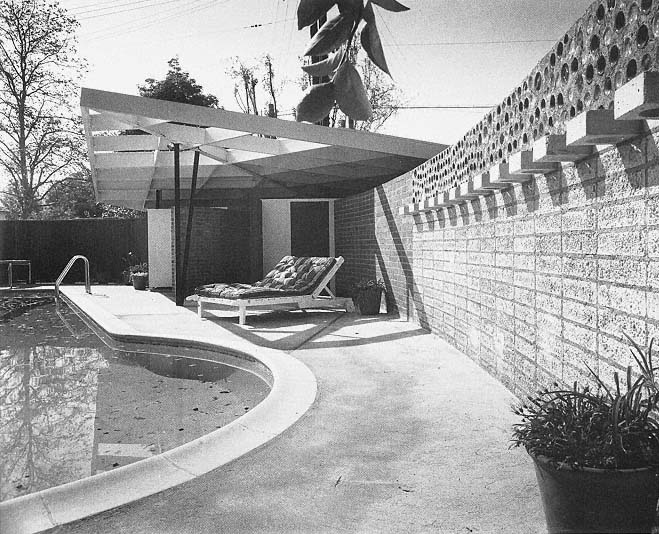

Goldstone garden. Bath house. Beverly Hills, 1948.

[Julius Shulman ]

the old-fashioned garden, bog garden, the English garden—all attempting to recall an emotion." Commercial planting, perhaps the most problematic of the four, "tend[ed] to move nursery stock most readily available . . . without thought to future development or consequences."[94] Today these were untenable, he held, without considering three additional factors: selection, arrangement, and maintenance [figure 68, see plates V, XVII].

Once again, Eckbo balanced his argument using pragmatic with aesthetic factors. "Structural forms follow all variations of symmetry and variety" using their texture, color, and scale to advantage [figure 69]. But selection should not be made in isolation, and it is the arrangement of plants—their use in combinations—that ultimately governs their success as contributors to the garden. "Most landscape plans start at relating a geometric structure with an irregular site; this requires a concept of form that combines the qualities of more rational geometrical organization with those of nature's free luxuriant growth and continuous development."[95] The final constraint, maintenance , colors the reasoning behind selection and arrangement—together, the triad govern the choice of plant species in the contemporary garden.

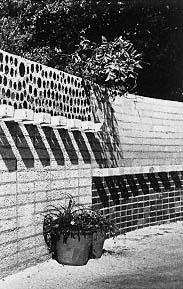

In several of these gardens the planted areas were reduced in dimensions, using singular trees and vegetation in metal or concrete planters as sculptural forms set against planar backdrops [figure 70]. The sun-catching and thermal-retaining Goldstone garden's wall "of brick, pumice blocks, and bottles, endeavors to extract a maximum expression from the materials by an expanded structuro-sculptural-mural treatment" [figure 67]. This same project also illustrated Eckbo's acknowledging maintenance as a key factor in garden design. For those interested in gardening as a pastime, or for those with sufficient land and means, involved planting schemes were both appropriate and enjoyable. But for those with more limited time, space, funds, and interest, those areas of the garden requiring tending should be kept to a minimum.[96]

67

Goldstone garden. The textured masonry

and bottle wall. Beverly Hills, 1948.

[Julius Shulman ]

Outdoor structures such as pergolas and trellises played an important role in both defining the garden space and accommodating the needs of the family [figure 71]. Occupying a niche between architecture and landscape, these structures, like the shapes of paved areas,

68

Rich garden. Los Angeles, mid-1950s.

[William Arlin, courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

69

Webb garden. Palos Verdes, late 1950s. The use of planting

within the garden, paired with the frame created by the bench,

established the comfortable relationship between near and far,

inside and out.

[Julius Shulman ]

70

The architectonic framework of the garden enriched with vegetation. Carlos Diniz, delineator.

[ from Garrett Eckbo , The Art of Home Landscaping]

71

Koerner garden. Palm Springs, late 1950s. The overhead

trellises provided much-needed shade for human and plant alike.

[Julius Shulman ]

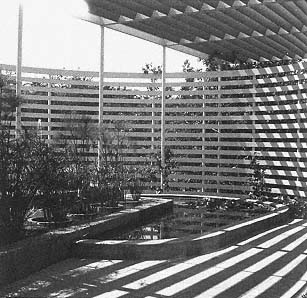

72

Goetz garden. Holmby Hills, 1948. Trellis materials

were used both overhead and in the curving screen wall,

creating a dazzling pattern of light and shadow.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

73

Goetz garden. Holmby Hills, 1948. Edgardo Contini,

engineer. The structure bounding the living area

combined a bench, wall, and roof in a single form.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

74

Edmunds garden. Main terrace railing. Pacific Palisades,

1956.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

set the tone of the design. For the Goetz garden in Holmby Hills, Eckbo fashioned an overhead trellis that—like the lath house—produced an active pattern of stripes of light and shadow [figure 72]. The metal bents of the pergola become wall and roof simultaneously, railing as well as garden limit [figures 73, 74]—an idea also pursued in the pergola-as-railing of the Edmunds garden in Pacific Palisades.