Eight

"Spacious, Suave, Sonorous, and Monastic"

The Modernist Architecture of Yoknapatawpha

William Faulkner, the literary modernist, was generally unsympathetic to the modern movement in architecture, a phenomenon not unique in the history of twentieth century modernist culture. Though certain avant-garde writers, painters, sculptors, composers, and architects eagerly embraced parallel developments in related fields, others were unable or unwilling to make the connections. To a certain extent, this antipathy was true for such writers as James Joyce and T. S. Eliot, and it was even more markedly the case with Faulkner. Like them, Faulkner seemed unable to identify his own literary experiments in cubistic simultaneity with related revolutions in painting, sculpture, and architecture.

Modernist architecture, like the other modernist arts, arose from a variety of sources and venues in the late nineteenth century, but few historians of the subject would question the assertion that a major source of activity was the burgeoning city of Chicago, which seized the opportunity for new techniques and forms after the Great Fire of 1871 necessitated an almost complete rebuilding of the central city. Led by such visionary pioneers as Daniel Burnham, John Root, and Louis Sullivan, the resulting "Chicago School" of skyscraper architecture forged the development of the epochal steel frame and of the modernist credo that the form of a building should express and articulate its function, its structural essence, and its meaning in time and place. In the early twentieth century, Sullivan's disciple Frank Lloyd Wright, and his so-called Prairie School, transferred the structural and aesthetic principles of skyscraper design

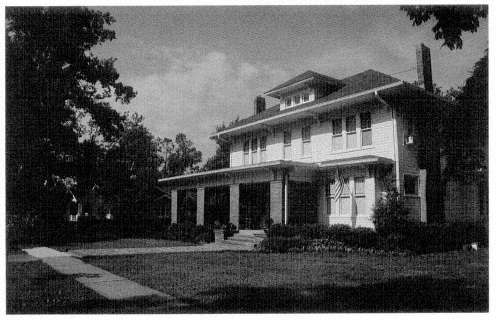

Figure 77

Beanland-Young House, Oxford, Mississippi (ca. 1905).

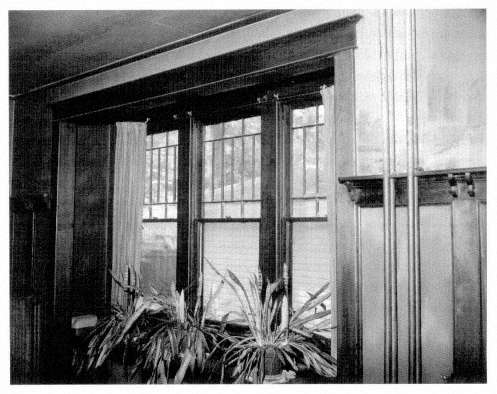

Figure 78

Beanland-Young House, interior.

to the private residence and the smaller public building and conveyed the "Chicago" principles of elegantly simple, functional modernism to the world.

Unlike the literary modernism of Joyce, Eliot, and Faulkner, which quoted richly from the whole history of civilization, architectural modernism moved from the late nineteenth century in a relatively more determined line toward the "pure," "new," and "original" forms of the International Style and its kindred mode, the Streamlined Moderne, of the 1920s and 1930s. Though most architects of these persuasions seemed to be striving for a transcendence of things past, many modernists were enamored of the elegant austerity of classical Japanese design and of the stark, white, skeletal ruins of antiquity. Yet the dominant references of the new twentieth-century architecture were the more consciously contemporary images of the Machine Age—as allied to, and expressive of, the conditions and "functions" of "modern life." Though most Mississippians, like Faulkner himself, professed a disdain for modernist architecture, the medium nevertheless made its way into the state. In 1889, two of Frank Lloyd Wright's earliest "Shingle Style" house designs were built facing the Gulf, side by side in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. One of these was a vacation house for Wright's mentor, Louis Sullivan. In the early twentieth century, the popularized versions of Wright's Prairie School and the kindred Craftsman-style bungalows of the designer Gustav Stickley could be found in Oxford and Ripley and most small Mississippi towns. Both types were usually filled with the familiar Craftsman or "Mission" furniture of Stickley and his followers.

In Oxford, the Beanland-Young house (ca. 1905), built by a modest tailor, Edward Beanland, later mayor of Oxford, nestled among its neoclassical and Victorian neighbors on stately South Lamar. It represented, with its unencumbered horizontal lines, its low-slung hipped roof, and its darkly handsome interior paneling, a vaguely regional version of the Craftsman-influenced Prairie style. In certain variants, it was known as the "four-square" style (Figs. 77 and 78). In Ripley, on "Quality Ridge," near the older homes of the Thurmond, Murry, Falkner, Hines, and Spight families, the related Bostwick family, in the early 1920s, built a large, brick, one-storey, up-to-date version of the low-slung Craftsman bungalow, a mode that appeared in variant versions throughout most Mississippi, and American, towns.

In the 1930s especially, local Mississippi versions of the stark International Style and the more ebullient, curvilinear Streamlined Moderne became the style of choice for

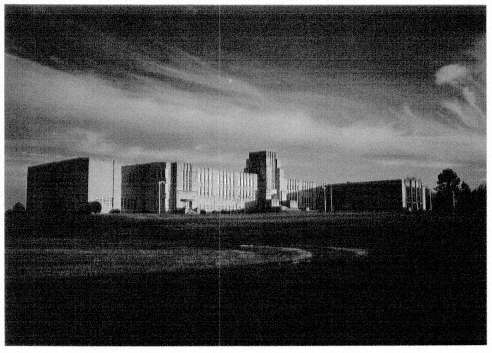

Figure 79

Columbia High School, Columbia, Mississippi, Overstreet and Town, architects (1937).

federally funded projects of the New Deal's Works Progress Administration (WPA) and its related "alphabet-soup" recovery agencies. Of particular eminence among Mississippi architectural firms who worked in these idioms was the Jackson office of Overstreet and Town, who throughout the 1930s designed brilliant buildings that gained national recognition, including the superb Columbia High School, Columbia, Mississippi (Fig. 79); Bailey Junior High School, Jackson, Mississippi (Fig. 80); and such fetching, if modest, structures as a hospital for the small Delta town of Rosedale.

The style reached Oxford, not in a building by Overstreet and Town, but by their gifted colleague, James T. Canizaro (1904-1982), who in 1938 designed a small modernist gem in the WPA-sponsored Oxford City Hall (Figs. 81 and 82). Canizaro, a native of Vicksburg, studied architecture at Notre Dame in the late 1920s, after which he worked in the great Chicago office of Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White, the successor firm to the pioneering D. H. Burnham and Company. In the early 1930s,

Figure 80

Bailey Junior High School, Jackson, Mississippi, Overstreet and Town, architects (1936).

Canizaro traveled to Europe where he made pilgrimages to, and photographic records of, the modernist masterworks of Walter Gropius and other members of the German Bauhaus school. In the mid-1930s he returned to his native state, where in Jackson, the capital, he rented office space from the more established firm of Overstreet and Town. He was especially close, both professionally and personally, to Hayes Town, and the aesthetic affinities were obvious in his work. In a state where the capital was the only place that seemed remotely urban, Canizaro knew that, in the beginning at least, he would have to seek work in small-town Mississippi, and he thus began to cultivate connections when and wherever he could.

In 1937, Canizaro obtained a commission in Oxford to design a sleekly modernist concrete apartment house on University Avenue at South 11th Street, a mildly regional version of the radical International Style. With the completion of this building, he told his colleague Henry Mitchell, he won the friendship and support of Oxford mayor

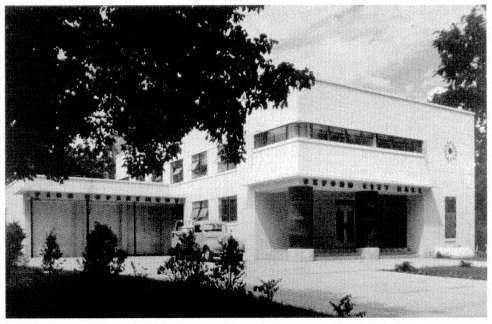

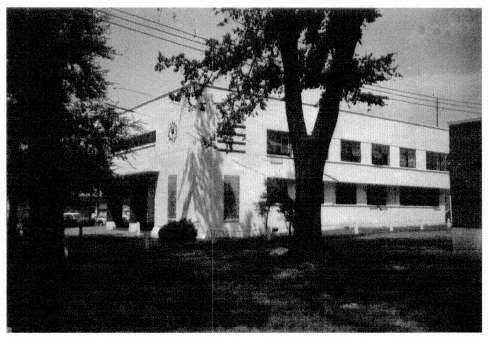

Figure 81

City Hall, Oxford, Mississippi, James T. Canizaro, architect (1938, demolished).

Robert X. Williams, councilman Branham Hume, and such civic leaders as businessman Will Lewis. This no doubt facilitated his winning the commission to design the city hall, a structure that pushed even more courageously toward the brave new world of international modernism. [1]

Above two round modernist columns supporting the covered first floor entrance porch, the defining motif of the building was a long, thin band of contiguous ribbon windows, curving smartly at the corner in a quintessentially modernist gesture. To the right and on the axis of this key design element was an asymmetrically placed clock of chic modernist design. Below the clock was a metal tablet relating the history of Oxford in a stylish moderne typeface, a summary, in effect, of the history of Yoknapatawpha. This typeface was repeated in a magnified form in the letters over the from entrance announcing the name of the building. Connected to the hall on its northwest side was the Oxford Fire Department, whose up-to-date engines and firefighting equipment seemed appropriately at home within the streamlined architecture. Like

Figure 82

City Hall, Oxford.

his fellow Mississippi modernist William Faulkner, Canizaro was experimenting with brave new forms—nudging his state against its will, with Sisyphean commitment, into the modern world.

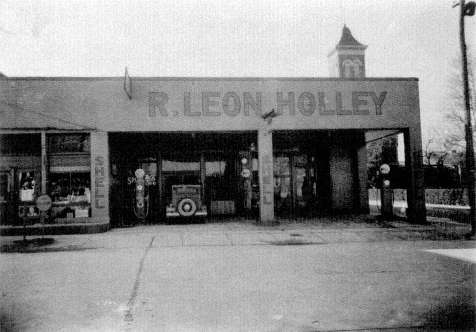

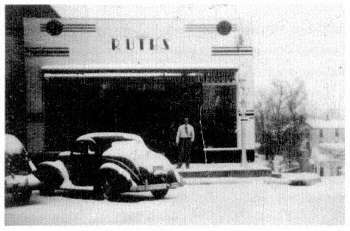

Except for the Moderne movie marquee of the Ritz Theater, just west of the Square, Canizaro's apartment house on University Avenue, the Holley Auto Garage on Van Buren Avenue (ca. 1930; Fig. 83), and the Art Deco facade of Ruth's Dress Shop on the Square, the first air-conditioned store in Oxford (1938; Fig. 84), the suave City Hall was the only visible architectural evidence that Lafayette County existed in the mid-twentieth century. Faulkner probably detested it, as did most of tradition-drenched Oxford. In the 1970s, the building, lacking supporters, was demolished and replaced by a blandly undistinguished structure for a new federal court and post office building, with a trade-off conversion of the old Federal Building into the Oxford City Hall. The needless demolition of Canizaro's gem suggested that twentieth-century Oxonians were less architecturally adventurous than their nineteenth-century prede-

Figure 83

Holley Garage, Oxford, Mississippi (ca. 1930, demolished).

Figure 84

Ruth's Dress Shop, Courthouse Square, east side,

Oxford, Mississippi (1938, demolished).

cessors, none of whom apparently protested an architectural evolution resulting in the integrated diversity of pioneer log houses, Greek Revival mansions, Gothic Revival churches, Italianate villas and Richardsonian Romanesque federal buildings.

Though Faulkner never referred explicitly to Canizaro's building in his work, he probably would have agreed with the evaluation of it by the critic Ward Miner, who visited Mississippi in the early 1950s and, in his short, pioneering book, The World of William Faulkner , made flawed but insightful attempts to relate Oxford to Jefferson. The City Hall, Miner argued, was "an angular, garishly modern structure. . . . It is unfortunate that such a design was chosen, since it clashes with the rest of the community." In Sanctuary , Faulkner had used similar imagery to denote perversity and disequilibrium, as he observed the manner in which Popeye walked, his tight suit and stiff hat all angles, like a modernistic lampstand .[2]

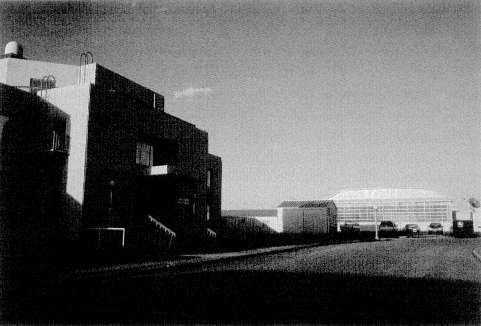

The only types of modernist buildings to which Faulkner seemed sympathetic were urban skyscrapers and structures connected with airports. Long addicted to aviation, he celebrated the hangars of the New Valois airport in Pylon as steel and glass caverns with the main building emerging as unabashedly modernistic, spacious, suave, sonorous, and monastic , the latter a reference to its minimalist austerity. In its bronze and chromium lobby, the building's interior murals presented the furious, still, and legendary tale of what man has come to call his conquering of the infinite and impervious air . Though "New Valois" suggested New Orleans, a contemporary model closer to home was the new, modernist Memphis Airport, which Faulkner knew well (1938; Fig. 85).

In fact, the exceptions to Faulkner's antimodernist bias seemed to lie only in his fascination with airports and with very tall buildings. In The Sound and the Fury , he had his sensitive alter ego Quentin Compson remark, with apparent pleasure: Father brought back a watch-charm from the Saint Louis Fair to Jason: a tiny opera glass into which you squinted with one eye and saw a skyscraper .[4]

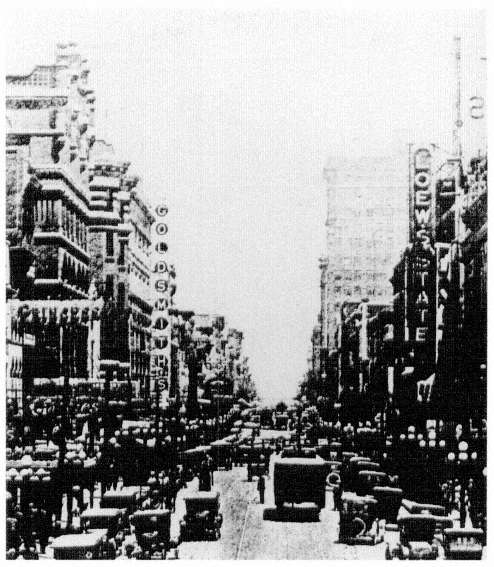

Indeed, Faulkner came closest to being seduced by modernism in the purposeful excitement and traffic of the city. In Sanctuary and particularly in the story "Dull Tale," he seemed to celebrate the modern urban environment: Where Madison Avenue joins Main Street, where the trolleys swing crashing and groaning down the hill at the clanging of bells which warn and consummate the change of light from red to green, Memphis is almost a city . At the intersection of Main and Madison, where four tall buildings quarter their flanks and form an upended tunnel up which the diapason of traffic echoes as at the bottom of a well, there is the restless life and movement of cities; the hurrying and purposeful going to-and-fro (Fig. 86). [5]

Figure 85

Main Building, Memphis Airport, Memphis, Tennessee,

Walk Jones Sr. and Walk Jones Jr., architects (1938), with earlier hangars.

Faulkner was more ambivalent about another modernist intrusion onto the Yoknapatawpha landscape: the vast New Deal flood-control project (1938-42) that dammed the Tallahatchie River and created Sardis Lake, an artificial reservoir that covered hundreds of square miles in western Lafayette and eastern Panola counties. The dam itself was a giant, mile-long mound of earth, one of the world's largest, with sculpturally modernist steel and concrete elements framing the spillway and the water level control towers (fig. 87). With handsome irony, these modernist totems hauntingly echoed the predecessor structures of Indian mound and grain silo, now submerged in the high water months, their tops reemerging as the lake subsided. In the late 1950s, Faulkner's friend Ella Sommerville remarked wistfully and ironically that much of her family's farm property was now at the bottom of Sardis Lake, as—alas—"Sutpen's Hundred" would also have been. It was the fateful merger of two mythical worlds—Yoknapatawpha and Atlantis. [6]

Faulkner himself loved to sail on Sardis Lake and to fish and hunt in its marshy backwaters, where he must have been moved by the islandlike tops of the vestigial

Figure 86

Main Street, Memphis, Tennessee (late 1920s).

Figure 87

Sardis Dam and Sardis Lake, Panola and Lafayette counties (1938-42).

Figure 88

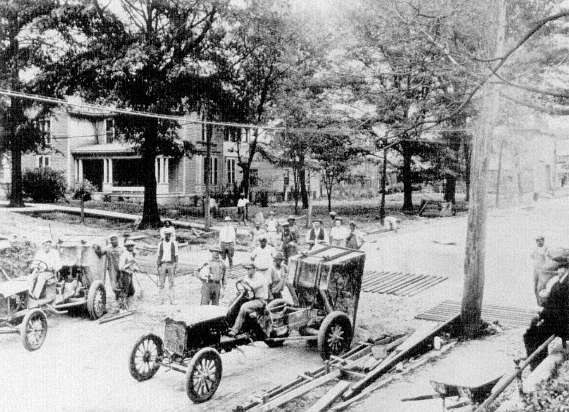

Paving Van Buren Avenue, Oxford, Mississippi (1928).

Chickasaw mounds. In his fiction, strangely enough, he never exploited the fertile potential of this modernist inundation, though in his great prose poem "Mississippi," he evoked it with irony and pathos: And now the young man, middle-aged now or anyway middle-aging, is back home, too, where they who altered the swamps and forests of his youth have now altered the face of the earth itself; what he remembered as dense river-bottom jungle and rich farmland is now an artificial lake twenty-five miles long: a flood-control project for the cotton fields below the huge earth dam . . . loving it even while hating some of it: the river jungle and the bordering hills, where still a child, he had ridden behind his father on the horse after the bobcat or fox or coon or whatever was ahead of the belling hounds and where he had hunted alone when he got big enough to be trusted with a gun—all this now the bottom of a muddy lake being raised gradually and steadily every year by another layer of beer cans and bottle caps and lost bass plugs .[7]

With the exception of the airplane, Faulkner professed to hate machines—the automobile, radio, phonograph, and television—and he associated them—correctly—with what he considered the equally intrusive forces of architectural modernity. He seemed, indeed, to regret not only the appearance of modernism but even more the disappearance of the world it sometimes replaced. However admirably left-of-center Faulkner may have been on such crucial social issues as race relations, in most other ways he was dauntingly conservative. In the summer of 1927, for example, there was a concerted effort by the Oxford town fathers to pave the major streets. No longer would citizens have to walk through inches of mud on the square left after every rain (Fig. 88). Most Oxonians were delighted, but one—William Faulkner—opposed it because he saw it as the breaking of another link with the past.

In Sanctuary , written about the time of these improvements, he spoke through his character Horace Benbow in an unabashedly nostalgic homage to textures, shapes, and colors lost: The street was narrow, quiet. It was paved now, though he could remember when, after a rain, it had been a canal of blackish substance, half earth, half water, with murmuring gutters in which he and Narcissa paddled and splashed with tucked-up garments and muddy bottoms, after the crudest of whittled boats, or made loblollies by treading and treading in one spot with the intense oblivion of alchemists. He could remember when, innocent of concrete, the street was bordered on either side by paths of red brick tediously and unevenly laid and worn in rich, random maroon mosaic into the black earth which the noon sun never reached; at that moment, pressed into the concrete near the entrance of the drive, were the prints of his and his sister's naked feet in the artificial stone .[8]

Faulkner was understandably depressed in the 1940s by the demolition of some of the second-floor porches around the Square, and he was even more disturbed by the needless destruction of the antebellum Cumberland Presbyterian Church on South Lamar Street. In protest, for years he refused to enter the modernist Kroger Grocery Store that replaced it. And the recurring rumors that the "inefficient" courthouse might be replaced he found unthinkable. He must have grimaced at the ungainly extensions to its east and west sides that were made to the building in the 1950s. In Requiem for a Nun , he expressed the fear that every few years the county fathers, dreaming of bakshish, would institute a movement to tear it down and erect a new modern one, but someone would at the last moment defeat them; they will try it again of course and be deflated perhaps once again or even maybe twice again, but no more than that. . . . [I]ts doom is its longevity .[9]

In Requiem , appropriately, he chanted a requiem for the old environment, mourning the losses with unabashed chauvinism: gone now from the fronts of the stores are the old brick made of native clay in Sutpen's architect's old molds, replaced now by sheets of glass taller than

Figure 89

Reflections of the Confederacy, Courthouse Square, Oxford, Mississippi (1950s).

a man and longer than a wagon and team, pressed intact in Pittsburgh factories and flaming interiors bathed now in one shadowless corpse-glare of fluorescent light; and now and at last, the last of silence too: the county's hollow inverted air one resonant boom and ululance of radio: and thus no more Yoknapatawpha's air nor even Mason and Dixon's air, but America's: the patter of comedians, the baritone screams of female vocalists, the babbling pressure to buy and buy and still buy arriving more instantaneous than light, two thousand miles from New York and Los Angeles . (Fig. 89). [10]

In fact, Faulkner's disinclination to appreciate the social and aesthetic significance of modernist architecture was no doubt one of the reasons he failed to identify with Los Angeles, the venue, next to Oxford, where he spent the largest part of his professional life. Living there periodically, he claimed, only to make money writing screenplays, he was unmoved by the fact that Southern California was one of the world's most important repositories of twentieth-century modernism. Because he failed to appreciate this, Faulkner chose to focus on the frequently ridiculous mimetic architecture of the area, the historicist cacophony of pseudo-French chateaux, English castles, and Egyptian tombs that echoed the movie sets of the Hollywood backlot. Hence, Los Angeles, or "Hollywood," as Faulkner referred to it, seemed shallow, rootless, and artificial. While numerous significant film-industry figures, such as directors Albert Lewin and Josef von Sternberg and producer Carl Laemmle, commissioned important modernist buildings from such avant-garde architects as Richard Neutra, Faulkner shared the popular image of Hollywood taste as confined to historicist kitsch. Faulkner was not alone in condemning such fakery. Like his fellow novelist Nathanael West, he disparaged the jerry-built, false-front follies that pervaded the area. In Faulkner's short story "Golden Land," for example, the buildings of Los Angeles County were scattered about the arid earth like so many scraps of paper blown without order . Indeed, had he been more disposed to appreciate modernist architecture, Faulkner's view of Los Angeles and the years he lived there might have been a more balanced one. [11]

Though Faulkner generally disapproved of modernism, he took an even grimmer view of antique reproductions, the sphere, in Yoknapatawpha, of the upstart, parvenu Snopeses. In The Mansion , he drolly satirized popular images of Southern architectural grandeur in the Snopes's "renovation" of the old de Spain house, which, with all its new "colyums," still wouldn't be as big as Mount Vernon . . . but then Mount Vernon was a thousand miles away so there wasn't no chance of invidious or malicious eye to eye comparison .

Figure 90

Avent Acres, Oxford, Mississippi (built late 1940s).

In The Town, ever afternoon after the bank closed he would have to go and watch how the carpenters was getting along with his new house (it was going to have colyums across the front now, I mean the extry big ones so even a feller that never seen colyums before wouldn't have no doubt a-tall what they was, like in the photographs where the Confedrit sweetheart in a hoop skirt and a magnolia is saying good-bye to her Confedrit beau jest before he rides off to finish tending to General Grant ).[12]

Faulkner's snobbishness was less playful and hence less defendable in his disdain for the subdivision of the old estates and the building of plain, thoroughly respectable tract houses for families of modest income, as in Avent Acres, Oxford (Fig. 90). In Requiem , ominously, there were new people in the town now, strangers, outlanders, living in new minute glass-walled houses set as neat and orderly and antiseptic as cribs in a nursery ward, in new subdivisions named Fairfield or Longwood or Halcyon Acres which had once been the lawn or back yard or kitchen garden of the old residencies (the old obsolete columned houses still standing among them like old horses surged suddenly out of slumber in the middle of a flock of sheep ).[13]

Faulkner was, at best, ambivalent to modernism, partially because the siting of new, modernist structures frequently seemed to call for the demolition of significant older ones. Though certain modernist phenomena clearly excited him, he mourned

the related absence of what would come to be called a preservationist sensibility. In Yoknapatawpha and elsewhere, he was certain, there was an insufficient recognition of the power and presence of the past in the present. Perhaps, ironically, Faulkner could not understand that this also included the recent past and the monuments of the early modern movement, which, like all architecture, still constituted in the human experience the best example of the visible, tangible past.