Stewart Stern (1922–)

1951

Teresa (Fred Zinnemann). Co-story, co-script.

Benjy [short subject] (Fred Zinnemann). Original story, script.

1955

Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray). Script.

1956

The Rack (Arnold Laven). Script.

1957

The James Dean Story (Robert Altman, George W. George). Screen story, script.

1959

Thunder in the Sun (Russell Rouse). Adaptation.

1961

The Outsider (Delbert Mann). Script.

1963

The Ugly American (George H. Englund). Script.

1968

Rachel, Rachel (Paul Newman). Script.

1971

The Last Movie (Dennis Hopper). Co-story, script.

1973

Summer Wishes, Winter Dreams (Gilbert Cates). Script.

Books include No Tricks in My Pocket .

Television credits include "Thunder Silence" (Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse, NBC, 1954), "Sybil," and "A Christmas to Remember."

Academy Award nominations include a co-story nomination for Teresa and Rebel Without a Cause (Nick Ray's credited story only), and best script (based on material from another medium) for Rachel, Rachel.

Writers Guild awards include best-script nominations for The Ugly American and Rachel, Rachel .

When my cousin Arthur [Loew] was nine years old and I was twelve, I went to spend weekends at his father's [Arthur Loew, Sr.] estate at Glencove, Long Island, which was a "Great Gatsby" estate that had come down from Marcus Loew. It was a neo-Renaissance Italianate palace with everything from a Tiffany glass-dome breakfast room to a nine-hole golf course, a dairy farm, two private yachts, and a seaplane that he would use to commute to the city every day. It was everything you read about. And that was slumming, because we'd spend the summers at the Zukor estate [Mountain View Farms at New City, New York], which was 1,000 acres with an 18-hole golf course. Did you see this? [Points to an inscribed photograph of Mary Pickford .] That's where Mary Pickford used to come on weekends.

Anyway, there were a lot of guests one weekend, so they had me in a room with Arthur. And Arthur sat up in bed and he said, "What we're going to do is go to MGM and we're going to be big shots. That's what we're going to do. And we're going to live together."

I can't tell you how many years passed before I saw him again. Arthur had asthma as a kid, so he moved to Arizona. I was raised in New York and went to the University of Iowa. Went into the army. Came back, was in a show in

New York. Came to Hollywood. Arthur was still in Arizona; he had been in the Signal Corps in Beverly Hills, fighting the "Battle of Beverly Hills."

All of a sudden I got a call one day and Arthur said, "Well, you'd better look for an apartment if we're going to live together and work at Metro." We got an apartment. By then, I was already a dialogue director at Eagle-Lion Studios.

Was Arthur your good-luck charm?

In a way. I mean, he was adored by everybody because he was so funny and so generous. He and I were just the odd couple. I would be worried about him staying out late and fussing over his drinking and making breakfast for God knows who would come out of the bedroom. And besides being my best friend, Arthur really respected my talent and made a wonderful habitat for me to write in. Later on, Arthur produced what I think is one of the best scripts I've ever done, which is The Rack . I thought he produced it elegantly; he resisted all temptation to do what the studio wanted him to do.

How did coming from a real Hollywood family affect you?

Negatively.

How so?

Uncle Adolph, he would never hire me. Sam Katz [a business friend of the family and an executive at Paramount and later at MGM], who had known me since I was born, wouldn't either. Uncle Adolph always said [in a growling, Yiddish accent ], "Ven you ready, you come and ve'll send you to Paramount. Ve need talent!" So, right after I got out of the army, I went. I told him, "I want to work for the studio." He said, "I have nothing to do vith it. You have to talk to [Paramount executive] Henry Ginsberg."

So I went to see Henry, and Henry said, "What do you do?" I said, "I'm an actor and I'm a writer. I'm Phi Beta Kappa . . ." He said, "Well, how do I know you're an actor if I've never seen you act?" I said, "You don't." He said, "How do I know you're a writer?" I said, "I can give you something I've written." He said, "I don't read. . . . Give my regards to your mother." That was the end of my chances at Paramount.

What was the problem?

I don't know. Didn't want to be accused of nepotism? His son and his grandson were [already] working there. Anyway, I was making the rounds of all the producers on Broadway. And Joe Fields, whom my mother knew because he had married the divorced wife of a distant cousin of ours, said, "Why don't you send him in and I'll interview him." Joe had written a play.[*]

* Joseph (Joe) Fields was a prominent writer, in Hollywood off and on from the early 1930s, of light fare, comedies, and musicals. He wrote many Broadway plays, including collaboration with Jerome Chodorov on My Sister Eileen (film version, 1942), and Junior Miss (film version, 1945). He also collaborated with Anita Loos on the musical Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (film version, 1953), with Peter de Vries on The Tunnel of Love (film version, 1958), and with Joshua Logan on Flower Drum Song (film version, 1961).

He hired me to be the assistant stage manager. Then I understudied the lead. I played the lead one night in a preview and everyone thought I was wonderful.

What play was this?

It was called The French Touch . René Clair directed it. René Clair was amazing. He had the only black pinstripe suit that I had ever seen that had crimson stripes. He was elegant, elegant. He looked like a ballroom dancer, like a Valentino. Very petite, intense, wonderful. Where were we?

About Joe Fields and breaking into Hollywood . . .

So then I went out to California and went to see Sam Katz, my second ace in the hole. Sam did take some of my stories and send them to the story department. I still have the report that came back, which said, "The kid has talent, sensitivity, but nothing for us. He's not commercial." That was the end of that . There were no favors coming from anywhere.

Then Joe Fields came out at the invitation of Brynie [Bryan] Foy, who was starting up this new studio called Eagle-Lion that was going to make low-budget films. Brynie Foy asked Joe to be writer-in-residence and to direct some things. So Joe called me up and said, "What are you doing? Come over for Sunday brunch. Marian and I would like to see you." I went over and he said, "What's happening? What studio are you working for?" I told him the story. He said, "That's disgraceful. The hell with them . I'm gonna put you to work. You come to Eagle-Lion on Monday and only say yes. No matter what you hear me say, you agree."

So I went in and he took me to the head of the studio and he said, "Stewart directed the road company of My Sister Eileen . He did the Chicago company of Junior Miss . . . ." Joe lied about everything . He said, "It's amazing that this phenomenal kid has been able to accomplish so much in such a short time . . . and fight the war for all of us."

So they hired me for seventy-five bucks a week as dialogue director. That's where I began.

Joe Field's deception worked so well. Did it teach you that, as many people believe, to succeed in Hollywood you often have to bend the truth?

No. I always played it fair and square, but only out of self-defense. I warned everybody about what I was like to work with. I'd paint the worst picture of myself. I'd say, "I'm slow, I don't know if I'll be able to finish this, I'm this, I'm that."

How did you get your break as a screenwriter?

Arthur Loew, Sr., had commissioned a script by Alfred Hayes called Teresa . Arthur, before he became president of MGM, gave it to me and asked me to look at it, make comments, tell him what was wrong. I took it away to a farm in Delaware. I wrote a list of about fifty questions, all of which were motivational. "Why this?" "Why did this happen?" "Why did this person react this way?"

I gave it to him and said, "This is not going to help anything. It's just really questions which let you know what I think is not fulfilled about the script." I'd never written a script, but my uncle took me seriously. He sent it to his co-producer in Switzerland [Lazar Wechsler, who co-produced The Search (1948) with Arthur Loew, Sr.], who wrote back and advised him to hire me to write the screenplay. So he did.

I knew that I didn't like Alfred Hayes' story. I didn't like the girl he had written. And when I say "didn't like," it's just that I didn't relate to them [the main characters]. I felt outside of them. And I didn't understand why the boy did what he did [in the story].

What I wanted to do was to tell the story of somebody who had a terrible war experience, but [to make the point] that the terrible war experience was not the result of the war. That it was the result of who he was before he got into the war.

Is that what happened to you?

Personally? No. But nowadays, you hear nothing but blame among the Vietnam vets: "It was the war that did it to me." My experience in World War II, although it was a very, very different war, was that a lot of people were badly damaged, emotionally and in many other ways. I don't believe, and didn't believe then, that it was the war that did it. I think that you are who you are and you take it with you. Maybe the war dramatized it in ways that had not been dramatized before.

Anyway . . . I went to the Veterans Administration and asked them to open up their files to me. I said, "I'd like to psychoanalyze [the character of Philip Cass, the highly sensitive World War II soldier of Teresa ] just from the symptoms I'm giving you. Then tell me as a result of the psychoanalysis what your prognosis would be for his relationship with a girl whom he met in an Italian village and brought to America as his bride. What the prognosis would be for his relationship with his father and his mother, given who they are."

They opened up their files to me. All the psychometric testing they'd done on individuals like that. Interview material. The notes that psychologists had made after the sessions. The material just absolutely opened the story up . . . and as a result, I got a much clearer idea of what motivated the character.

That's the way I have worked ever since, looking as deeply into the records available to me, to get as accurate a picture of the psychodynamics of the characters [of my scripts], as I possibly can. "Sybil" certainly is the prime example. With "Sybil," I was privileged enough to hear and be allowed to do transcriptions of all the actual sessions of analysis [by Dr. Cornelia Wilbur, who psychoanalyzed the real-life Sybil] that had been recorded. And Sybil sent me all of her journals so that I could follow the course of how those selves took over. It was really apparent in the journals how one would stop and another would take over.

Why did the psychological approach, in scriptwriting, work so well for you?

I think it had partly to do with my own therapy. I was very influenced by therapy. I've been through every kind. I went through a fourteen-year Kleinian analysis and didn't know it was Kleinian.[*] I was in analysis for five years with someone who was a Freudian. I've had eclectic this and that. I mean, it has never stopped.

I have to be sure that I really understand what the deepest psychological motivation is for whatever action I give the characters. Even if I'm doing an adaptation, I have to work that out for myself. The action of the script becomes the inevitable result of the psychological progression of the character. Not simply because that's what's given. It has to be justified—psychologically, emotionally, mythically.

You have said that this first experience as a scriptwriter, working with director Fred Zinnemann, scalded you .

He had a very difficult time understanding the script I had written that he had agreed to do after declining the one by Alfred Hayes. We had an endless period of rewriting in California after he had sent me to Italy to find the girl [Stern helped "discover" Pier Angeli] and to find locations. Arthur Loew, Sr., loved my first draft and he didn't see any reason to change it. Zinnemann kept wanting me to change it, but was very unspecific about how. What became apparent was that he really didn't understand the whole psychological understructure and was desperately trying to understand. Whether he was resisting it, whether it was too close to him emotionally, whether the "unheroic" dependency of my young soldier and veteran was threatening to him, I still don't know. I just know that his understanding slid in and out in a curious way: He would understand and then he wouldn't understand.

He asked me at one point to do a psychological explanation of every scene. So I retranscribed my entire script and put my dialogue on the left-hand side; and on the right-hand side, opposite every single line, I put the subtext, the psychological subtext of why that line was there and what its effect would produce in human behavior that he could direct. It was about three hundred pages long. I wish I still had it.

Zinnemann read it, and then came more revisions! Arthur Loew, Sr., was in New York, saying, "When are you guys gonna stop this and start casting the movie?" Finally, Arthur Loew, Sr., came out [to California] and said that we had one more week [to finish the script] and then he was going to put a stop to it.

Then Zinnemann sent the script to all the paraplegics who had been in the film he made with Marlon Brando for Stanley Kramer, The Men [1950]. He

* Melanie Klein's psychoanalytic belief is that infants who do not get proper mothering grow up seeking the mothering aspect in every relationship.

didn't think my treatment of soldiers was authentic. He didn't know why he didn't think so, but he didn't think so. Now, I had fought as an infantry man in the Battle of the Bulge, been declared missing in action, and had a fair idea of what soldiers were about, but whatever the comments of those paraplegics were, he began to give them to me. He seemed to be giving the script to people in order to get some kind of clarity about his own feelings.

One Sunday I was working on the script at home and I needed to get a version of a scene that I had left in our office at the studio, but I didn't have a key. I called Zinnemann and I went up to his house up above Mandeville Canyon. He gave me the office key and said, "It's in my briefcase." So I went to the office and opened his briefcase and took out the script. I opened the cover and there was something in his handwriting. It said something like "Stewart has no love. Stewart has no understanding of these characters. Find another writer. Maybe, get [Alfred] Hayes back."

Well, I guess the worst moment in my life, even to this day, was finding out, that way, what he really thought of me. I didn't know what to do. I cried. Barely made it back home. I copied the note. I still have it somewhere. I showed it to Arthur Loew, Jr., and he said, "Well, you have your choice: Either you can quit or you can go ahead." I decided to go ahead.

It was very rough for a beginning young writer whose confidence depended utterly on his teacher's good opinion, and Zinneman had taught me all I knew. I knew that as a story man Zinneman usually knew precisely when a story was right, just the way he did with performers. He often couldn't tell an actor what to do. But if the actor delivered it right, Zinneman could tell it was right. The same held true with story. But, in this case, it was very hard to be at the other end of his attempts to understand. The instructions were never very clear.

Yet you continued .

Part of the reason I continued was because I liked Fred, I was enormously grateful to him because he was the first one ever to take a chance on me, and I adored him as a director. Also, I knew that I had to stay close to the filming if the picture were ever to reflect my vision at all.

So I didn't say anything about the note and I did the rewrite. Then Zinnemann let me help him cast it. I prepared all the kids for their screen tests and was in the screen tests with them. He gave me an enormous amount of responsibility.

But the next thing that happened, another thing that nearly killed me, was that he wanted Bill Mauldin, the marvelous cartoonist for Stars and Stripes, to be technical adviser. At first, I thought, "That's fine." But when we got to the hotel in Rome, where we were preparing the Italian half of the film, Fred told me—rather mysteriously—that he wanted me to rewrite the American part of the story. He said, "The Italian part is fine now." I knew that

there were things about the Italian part that still needed work. But he kept insisting on that. We'd have lunch together and talk about the rewrites of the American section.

One day, Arthur Loew, Sr., called me to his room and said, "I have something very difficult to do." I said, "What is it?" He said, "Fred has been working with Bill Mauldin on the Italian half of the script while he's had you rewriting the American half. Bill has written a treatment, and Fred wants me to ask you to rewrite the [Italian] half of the screenplay from it." And he handed Mauldin's treatment to me.

I can't even . . . I don't want to bring back that moment, it was so ghastly. This had been going on without my knowing it. To a beginner who trusted everybody it felt manipulative, high-handed, cruel. I read what Mauldin wrote, and it had nothing to do with the sensibility of the character I was writing about—who was, of course, myself.

There were certain things that Bill did which were wonderful: a little vignette of two guys, after the war had ended, who were sitting in a shack with their homemade still, toasting V-E Day with canteen cups—it was a typical Mauldin cartoon. It was wonderful and I wanted to use that. There were one or two other things: the way the platoon sergeant took over the house where Teresa lived and told the lovely Italian family who lived there that the American replacements were simply moving in. Other things that were really wonderful ideas.

But I didn't want to use the treatment. I wanted to incorporate the ideas into what I had without disturbing the behavior of my character. I think it all came from Fred's need to make my story comprehensible. It was legitimate for him to ask Mauldin to collaborate. But not that way! The proper way would be to have the writer in and Mauldin in and say, "You two guys talk because I have a feeling that what Bill's seen here during the Italian campaign could really enrich what Stewart's done." Not to have someone come in and start dealing with your characters behind your back.

But I swallowed hard. Arthur Loew, Sr., said, "I love your script. I loved the first draft. But now we're in production and we have to move ahead. If you want to go home, go home and I'll understand. But I don't want you to. I need you here. I need you to protect this script. As far as I'm concerned, you don't have to change anything. But Fred is the director, and it would be a good thing if you could use whatever felt right."

So I did.

Arthur and I never raised this issue again. I never told Fred how betrayed I felt. The night before we started shooting, Fred called me to his room and said, "Stewart, I tried to get close to this story, but I have to admit to you that I don't understand a lot of it. Maybe it's the age difference. Because you're so much younger, and the character is close to you. You've been an

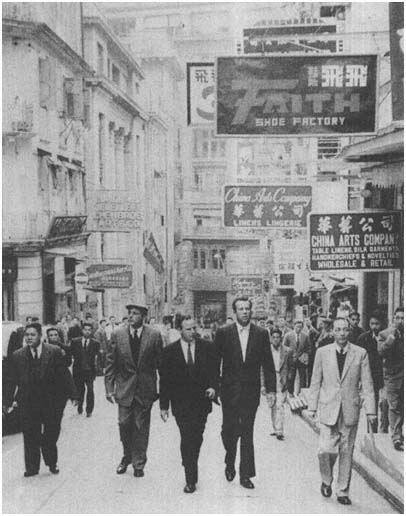

Stewart Stern with his mentor, director Fred Zinnemann (foreground), on location

in the Apennines for Teresa in 1950. (Photo: Harold Zegart; courtesy of Stewart Stern)

actor; maybe it would be good if you worked with these young actors alone. Prepare them for their scenes and show me the next morning what you did when we come to the set, and I'll stage it."

So that's what we did in all the scenes with Pier Angeli [who played Teresa] and John Ericson [who played the American soldier]. It revealed Zinnemann to be a very big man with a spacious spirit, a man in creative conflict

because of the curious nature of a subject which at the same time repelled and attracted him, yet a man who took a very big chance with me.

Why do you think he took a chance on you? Generosity? Desperation? What?

Probably a little bit of both.

Apart from Teresa, I know you worked on a treatment for Zinnemann called "Sabra," which was to star Montgomery Clift. Did you and Montgomery Clift become close friends?

He was someone I never knew what to say to. He was so bright, so funny. But I never knew what to say to him, so I would avoid him.

One night I got a call from . . . Dennis [Hopper]. He said that he was in New York and that they were all sitting around Monty's. I said, "Monty who?" He said, "Clift." I said, "Well, I'll come down, but I didn't even know you knew him." I went down there, and there was Dennis and Roddy McDowall and a bunch of people . . . all whispering in the living room. I said, "Why's everyone whispering?" They said [in a stage whisper], "Monty's asleep upstairs." I said, "Well, I want to see him." They all said, "Oh no! You can't go up." I said, "Why not?" So I went upstairs and just kept opening doors until I found a bedroom with a lump in the bed. I went in and sat on the bed and shook Monty until he sat up and screamed and threw his arms around me. He asked me what I was doing in New York and what I was up to. He asked, "Can't we get together?"

I said, "Do you like Bea Lillie?" See, Beatrice Lillie was probably the greatest comedienne who ever lived, the female Charlie Chaplin. She was replacing Rosalind Russell in Auntie Mame, which was a big hit on Broadway. She and I had become friends, so she had gotten seats for opening night for my parents, for me, and for someone [I'd like to invite]. I didn't have a date yet. So I asked Monty and he said he loved her . I was sure he would forget. Two nights later, I drove up in a taxi and he came stumbling out of that house . . . I don't know how much he had had to drink. His shirt was curled up, his tie was askew. My mother took over in the taxicab, smoothed him out, and he couldn't have been sweeter.

We went to the theater and sat in the third row. He laughed so hard. Nothing went right. Rosalind Russell had very long legs, so all the business was staged for her; she could cross that stage in three strides. Bea Lillie is five foot three. She would have to skip in order to be where she had to be on every cue. She had never worn wigs this way. She would have to take hats off, and the wigs would come with the hats! It was terrible! Monty couldn't stop laughing and neither could I. He was finally in my lap saying, "Am I embarrassing you?" But he had to be controlled, physically controlled, because he was throwing himself all over the aisle. Bea loved it. She didn't know who it was, but she knew that someone was down there having fits.

When it ended, we went backstage. The place was packed with people

waiting to see her—all being very elegant. Monty and I were kind of standing at the back. She saw us. She kind of waved to me. She said, "How was it?" Monty leans over somebody's shoulder and shouts, "Terrible! You were terrible!" And they had never met before. So she says [in a delighted tone], "Come right in to my dressing room." She took us in and closed the door. She just loved him for it. Of course, he didn't mean it at all. That was the night she showed us this amazing letter she had gotten from Jack Benny, who had read a review that Brooks Atkinson had written about her. Benny wrote her something like "Darling Bea, I've just read this review of your enormous success. Brooks Atkinson says that with the flick of your eyebrow you are the funniest person in the world. And I just want to give you my love. P.S. So why don't you just go fuck yourself?"

Afterwards, I remember, Monty and I went to a bar on Third Avenue and we both commented on how comfortable it was to be together. We had never been comfortable before, always very stiff. I said, "The thing that makes it easy is that your face is gone. I couldn't even look at you, you were so . . . impressive." (He was so beautiful before he had that terrible accident.)[*] I said, "It's probably not tactful to talk about it, but I find your face now so available, and it makes it possible for me to be with you. The other one kept me out. I wonder what it's like for you to be behind this face instead of the one you had?"

What did he say?

He said, "It's easier to be with you."

How did you get involved with Rebel Without a Cause?

Rebel came about because Arthur [Loew, Jr.,] made me go to a party at Gene Kelly's house. I had known Gene for a long time, but he was a star and I wasn't comfortable. He had invited Arthur over for dinner and to play charades. We went over that night, and among the people there were Marilyn Monroe and [director] Nick Ray. And Jimmy [James Dean] and [composer] Lenny Rosenman had gotten to Nick [about me]. Nick came over and said that he had seen Teresa and that he had liked it so much. We started talking and he said, "Why don't you come to the lot?" But I think even with Jimmy and Lenny speaking to Nick, had I not gone to that party, it might not have happened.

Was Rebel already in script form by the time Nick Ray hired you?

There were two [scripts]. There was a script by Leon Uris, which I never saw because they didn't show it to me. They did show me the script by Irving

* On the evening of May 12, 1956, Montgomery Clift's car "crumpled like an accordion" into a telephone pole on Sunset Boulevard. The actor suffered severe whiplash, a broken nose, and a broken jaw that was set incorrectly—and had to be rebroken and reset. As a consequence, his mouth was permanently twisted, the left side of his face immobile, his once-perfect nose bent. See Patricia Bosworth's Montgomery Clift (New York: Bantam, 1979).

Schulman, which I took certain elements from. There was one scene which took place in the Planetarium, not my scene, but I thought the Planetarium as a set was something so powerful and could really incorporate the speed at which [events in] the movie should go. That everything happens in one day. Impossible, but that's the way it feels when you're that age: You live and die a thousand times in a single day when you're a teenager. I knew that I wanted the picture to kind of begin and end there.

There were also character names [from the Schulman draft] that I used. But my script wasn't an adaptation [of his]. It was so little an adaptation that [Schulman] then was given permission by Warners to novelize his script as a book.

There was a seven-page outline that Nick Ray claims to have sold to Warner Brothers that started the whole project. It's something that I've never seen to this day.

How did Nick Ray describe the project once you were brought on board?

Nick told me about all of the research that he had done: about middle-class young people. He wanted it to be specifically about them because he said that there was a big misconception that so-called juvenile delinquency was a product of economic deprivation. He felt that it was emotional deprivation. He had done a lot of research, and one of the things that he wanted in the story was a "Chickee Run," which would happen in the Sepulveda Tunnel. That was one scene that he wanted in the movie. That was virtually the only requirement.

That's when, at my request, he called his contacts at Juvenile Hall, and I went down and began researching it. I spent ten days and ten nights there, or two weeks, posing as a social worker, talking to the kids or just being there when they were processed. Then they opened up all of the psychological workups that they had done down at Juvenile Hall on the kids they brought in. Family backgrounds, records of their behavior. Whatever they had, they opened up to me. So, I was able to dig as far as it was possible to dig, in order to understand who these kids were and to create a prototype.

I couldn't figure out what to write until I went to see On the Waterfront [1954] and got all charged up and came home and just began writing. But I wrote the script really as an original, keeping in a variation of the "Chickee Run" scene that Nick wanted and the names that Irving Schulman had created—a Jim and a Judy who loved each other, and a third one, Plato, who was sort of an appendix.

You'd have to inspect both scripts to see [how the final one] really developed. [Long sigh .] Anyway, there was a terrible situation at Academy Award nomination time, because in those days the story and the screenplay were nominated separately. The story was nominated . . . and Nick Ray had story credit. There had been no story until my script was written.

What did you do?

Well, Nick Ray claimed there was. He said, "I sold Warners my seven-page story," and I said, "Well, I've never seen it. . . ." He said, "What do you think was original from you?" and I said, "Nick! How can you ask me that?" He said, "Give me an example." I said, "For one, that this whole story took place in twenty-four hours. I remember coming to you at two in the morning once when I couldn't sleep and wanted someone to talk to, and I said I'd gotten this wonderful idea that it was all going to happen in twenty-four hours." He said, "That was in my notes before I even met you. . . . I'll tell you what: You give me co-screenplay credit and I'll give you co-story credit." I said, "But you didn't touch the screenplay! If you take story credit, then I want Irving Schulman to have adaptation credit, because he was there too." So he gave [Schulman] adaptation credit. But Nick got the nomination.

Later on . . . I was in Paris and noticed a book published in French. I can read some French, so I opened it up and it was my screenplay! Novelized! It was all my dialogue with the credit line "By Nicholas Ray." Not a mention of me! Not on the cover, anything. Not any acknowledgment that I had anything to do with it.

What did you do?

I told Nick that it wasn't very fair, and he said that he had nothing to do with it.

Was he a compulsive liar . . . or a Hollywood rat?

I don't think he was either a compulsive liar or a Hollywood rat. I think he was a man who was hungry for recognition, who really didn't trust that his talent was authentic. He adored Elia Kazan. Kazan was his model, and the first person he wanted that script to go to was Kazan.[*] He gave it to me to give to Kazan, and he wanted me to stay in Kazan's house while Kazan read the script. And I did. And Kazan read it. That was a bad experience.

Were you satisfied with what Nick Ray ultimately did with your script?

I was horrified. It was one picture that I had volunteered not to be present at during the shooting. Because once the script is done and the production is in process, the most important thing is the relationship between the director and the actor. The actors are completely without their skins. They're asked to reveal, without any chance to prepare, things about themselves that they have never revealed to anybody. That's what ends up on the record. To in any way upset that relationship is very, very dangerous . . . and is one reason why writers are not traditionally welcomed on the set. They don't know to cope with that, don't really appreciate that. The power of the writer who is standing in a dark corner of the soundstage, rolling his eyes to the ceiling . . . it can demoralize the cast and take them away from the director for the rest of the production.

* Coincidentally, director Kazan had just finished filming John Steinbeck's East of Eden (1955), Dean's first major motion picture.

Jimmy ran away just before they were going to start shooting Rebel . He disappeared. They were going to suspend him and cancel the picture completely. Finally, I got a call from him and he told me he was in New York, but he wouldn't tell me where. He didn't know whether to come back or not. "What are they saying?" I told him what they were planning. He said he didn't know whether to come back and to trust Nick. He said that he had turned himself over entirely to Kazan. He said, "Do you want me to come back and do this movie?" I said, "I can't tell you that, I really can't. Because if you're experiencing this kind of mistrust, I can't reassure you. But I know that Nick adores you and that he's passionate about this movie. Partially because he feels so guilty about what he's going through with his own son right now." He said, "If you want me to do it, I'll come back." I said, "You don't know the temptation I have to answer you the way I want to, but I can't." And I didn't. But he came back.

I knew that if I were there that Jimmy would be coming up to me after takes, or I would be going into that trailer. Even if I didn't talk about the picture, just the sight of me going into the trailer and closing the door and not having Nick Ray in there would have been a calamity for the film. Would have hurt Nick and put his anxiety just exactly where it shouldn't have been. He had a lot to think about. It would have not served Jimmy. This was something that the two of them had to work out for themselves.

Did you explain your absence to either of them?

No, I was simply about to start The Rack at MGM and I had an apartment in New York, and I said, "This is the best time for me to drive east and get my furniture and bring it all back here."

Then how did you handle rewrites on Rebel?

We had an agreement, Nick Ray and I, that I would call him every night and he would have rehearsed the scene from the next day. He would tell me if anything needed adjustment. I would do the rewrites overnight and would telephone him or Fay, his secretary. There were very, very few rewrites. Nick went back on his word because he did add some lines which I find incredibly offensive. Like when the mother, on being driven to the site of the Planetarium at the end [of the film], kind of looks into the camera and says, "[You] can't believe this really happens to you, until it happens to your children . . ." Something frindle like that.

Also, I felt that we were both unfair to the parents. [In my case] I was still in the process of thinking that if my father stood up, I could finally start my life.

Meaning?

The man I needed him to be—the father in Rebel . So I was blaming my parents for everything because I had just started analysis. Nick was blaming parents for everything because he felt guilty about his son—his mixed-up family life. So there was a slight exaggeration in the portrayal of the parents

which sometimes makes me cringe. I think the writing is good, and I like Jim Backus very much: He did a good job. But the casting—it's comedy casting of those parents. We just didn't give them any credit.

Was there was someone else you would have liked to have seen cast instead?

No. I think Jim Backus played it with extraordinary integrity. I just think, between the writing, the exaggeration, and the fact that the directing did not go against the writing at all, but simply implemented it, that the effect was simply an exaggeration. It wasn't really clear in the way the picture was shot that this was the interpretation of a very young person. That this was parents seen through the eyes of these kids.

Did James Dean have a lot of input in his lines?

Not at all. We had one reading where he and Nick and I sat down and went through the script together. Jimmy laughed, I remember, because I had him mooing in the Planetarium. That's how we met: mooing. That was the kind of signpost of our beginnings. He came up with some line, "Quick! Fill the pool . . ," but I don't know if that was on the set or that night.

Did he ever let you know how the role spoke to him as an actor?

He said he liked the script, it felt comfortable. He let you know in funny ways that he liked or respected you. He picked me up sometimes to go to the studio. There'd be mornings when I'd hear his motorcycle outside, and I'd come out and he'd be there waiting, saying, "Here, c'mon." And I'd get on the back or follow him in my car.

Do you remember where you were when you found out about his death?

Yeah. [Long sigh .] I was staying at Arthur's above The Strip. Henry Ginsberg, who produced Giant [1956], called. He was a great friend of Arthur's and an old friend of mine. He said, "Where's Arthur?" I said, "He's having dinner with Uncle Al on La Cienega at the Encore Room." He said, "The kid's dead." I said, "What are you talking about?" He said, "Jimmy was killed in an automobile accident. You gotta find Arthur and tell him before this gets on the radio."

Jimmy and Arthur were very close friends?

He loved Arthur. Arthur was one of the world's funniest people, and Jimmy would hang out at his place practically every night. . . . So, I went down to the Encore Room and went in and told Arthur. I was smoking a cigarette and it turned to . . . shit . . . in my mouth. Then, I just wandered around. I left the Encore Room because I wanted to be alone. I couldn't believe it. I turned on the radio. There was nothing on the radio. There was no confirmation in the real world that this had happened. I thought it couldn't have.

I walked up and down Hollywood Boulevard. I went to Googy's and had coffee. I looked around. Here were all these faces that were there when Jimmy would go in. Nobody knowing anything. I was afraid to say anything. I was afraid I'd be wrong. Then sometime during the night, there was an announce-

ment. And you could tell. You could tell in the way it was when Kennedy had been shot. Cars pulling off the road. Traffic stopping so people could control their agitation while they heard the news. It was like a strange wind that came right through the streets of Hollywood. People's rhythm changed. They began to pull into little groups like mercury rolling across a tabletop, collecting other little pieces of itself. Consoling each other. These eerie sounds, these cries would come up from places. It was a nightmare. But at least then I knew that the world knew and that it had really happened.

[Long silence. Stern begins to cry.]

Are you all right?

[Long silence.] . . . It was such a terrible loss. He was the only one that I've never gotten over. I think it's true for everybody: I know that this is true for Elizabeth [Taylor]. For Natalie [Wood]. For Dennis [Hopper], in his way. I don't know whether Dennis has ever mourned Jimmy, but he was tremendously affected. I can't explain it, what [Jimmy's] impact was. I've had better friends. I've certainly known people longer—it was only months that I knew Jimmy. I don't know what it is that makes his disappearance as much of an ache as it is. It's never abated.

How did the script for The James Dean Story [1957] come about?

There was a guy named Abby Greshler, who is an agent and a very nice guy. He called me about this movie about Jimmy which was, really, practically on the heels of his death. I was just so offended by the thought that anyone would do any such thing about him. So I said, "No."

Then all of the sudden this film came about [anyway]. And I told [the filmmakers] how I felt, and they said, "Well, we're going to do it anyhow. We've already shot all these interviews. So if you don't do it, somebody else will." So I figured that I had better do it.

I hated the James Dean legend because I didn't think it had anything to do with him. I thought that all the things that his character in Rebel said were not important to his fans. I didn't understand then what I understand now. That it's like a punk haircut. The leather jackets and the stomp boots in the days of Rebel were not marks of rebellion. I think they were emblems of the ridiculousness of the facade. They were saying, "This is the thing that the grownups can't see past . . . but we can. What we see is what they can't see, which is that we are human, we are loving, we are sweet, and we wish people no harm. . . ." Partly the fiction that the script provided: a child who simply could not please a parent, who tried in every way to grow up and was full of nothing but love. Who needed understanding . . . I didn't know what I had written, in a funny way.

[For The James Dean Story ] I wanted to present Jimmy in a different way. I wanted to make it a preachment against violence. I wanted to say through that documentary what I thought that Rebel Without a Cause had not said. I found letters of Jimmy's that talked about that and quoted them. And I tried

to create him as a sensitive, wandering soul that haunted the nights and tried to spread compassion to the world.

In a way, that was a fiction. That was a partial truth. Jimmy was much more complicated than that. It was also unnecessary and redundant . . . because that's what Rebel had said to these kids anyway. That's why they still see it.

What do you mean by "more complicated"?

[Long silence.]

If you had the chance to do it over again, would The James Dean Story be significantly different?

I would do it differently, but it would be difficult to do because I feel very protective of him. It's more important to me now that the legend be preserved than that the real Jimmy be known. One hears a lot about what Jimmy Dean really was and what he did to people and what his preferences were. And I don't think that's interesting. I think what's interesting about him is the legend that he left behind. It was that aspect that came out of East of Eden [1955] and out of Rebel and that young people generation after generation are responding to.

I'm disappointed in [The James Dean Story ]. I don't blame it for anything. I just think it was a very idealized partial piece of propaganda. For which I was entirely responsible. I was very moved by the language as I wrote it. Now, I would take a scissors to it. I would be a lot more prudent about some of those images. Stuff like walking on the beach, seeing the dead seagull. That stuff never happened to Jimmy! That was me doing stunts. . . . And I thought it was badly, badly hurt by Martin Gabel as the narrator.

I did a narration track myself, as a dummy track, just so we could see what the film looked like, and it was better than what [Gabel] did. He did to my words in a way what Nick Ray did. Instead of going against them, he larded them with his rich, vocal tones. Resonances that had nothing to do with the movie.

At the time, I pleaded with George [producer and co-director George W. George] and [director] Bob Altman to let Marlon do it. I wired Marlon—he was in Japan or somewhere—and told him about it. He agreed to do the narration. On the provision that the whole thing go to charity. Everybody's profit go to charity. That was not acceptable to anyone.

Then I tried to get Dennis [Hopper], because I thought he would be wonderful. They wouldn't hear of it. So they got Martin Gabel. I think that if there were a young voice reading that narration, a lot of my objections to the film, to what I wrote, would be gone. But I think it was written out of my own grief. My own feeling about being the custodian of the flame.

Were you able to connect with male stars you have worked with—Montgomery Clift, Dean, Dennis Hopper, Marlon Brando—because they were un-

able to express their angst and isolation in words? Because you too felt isolated, but as a writer could articulate it?

No. I don't think of it in terms of me functioning as a writer for them at all. It's more on a personal level. Those friendships went on for a long time. With Dennis . . . there was a kind of big falling out over The Last Movie . And though I don't see Marlon much, we talk from time to time. But nobody sees him.

I know with Marlon there's something that goes back to 1956, when we first met, and that is totally unbroken. I once got really frightened one night . . . I don't know why. I hardly knew Marlon, but I was scared. I couldn't stay in my apartment alone. I had a lot of friends, but the one person I thought to call was Marlon. I did. I said, "I'm scared," and he said, "Come up." I went up there at about one in the morning, and he was right at the door. He'd made some tea, a sandwich. He'd made up the guest room; the light was on. He couldn't have been more understanding. He didn't push, he didn't ask, "Why?" He just said, "If you want to talk, that's my room. Bang on the door anytime during the night." I had to be somewhere the next morning at about nine o'clock, so I just got up and left. We didn't talk again for maybe five months. You [rarely] encounter that kind of trust, especially on short acquaintance.

Independently, around this time, he, George Englund, and myself all got the idea of doing a film about the United Nations. About what the people did out in the field—the unsung people—in health, midwifery, agriculture. George, who was very young, not out of his twenties yet, somehow or other persuaded Y. Frank Freeman at Paramount to underwrite our adventure, so that the three of us could go in search of a story all through Southeast Asia.

Was it common for studios to be so generous towards a project still in the development stage?

No! Especially not without a property or a story or anything. The other thing George did, which was extraordinary, was to persuade the Secretariat of the United Nations to cooperate. They never cooperated [with film productions]. With Paramount Pictures? Why should they? They're supra-supranational. But they agreed. They sent word to every resident representative in Southeast Asia, in all the capitals of all the countries, that we were coming, and requested them to meet with us when we arrived and to bring in from the fields all the experts that we wanted to see. They were to expedite our visits and make us comfortable wherever we wanted to go. Unprecedented . . . and for this kid to organize it!

Marlon and George had a wonderful relationship. George was the top executive of Marlon's independent company called Pennebaker Films. I think Marlon, Sr., was president. They were the entity that Paramount was dealing with.

I remember one day, in 1956, when George took me up to Brando's house—

he lived on North Crescent Heights, up above the Strip, just above the Chateau Marmont, in a big house with a white tower. It was rented. We heard this drumming, and we paused on the spiral stair that went down this tower to the room where he was creating. He was whaling away at that drum, conga, bongos—he seemed to be playing everything at once. George whispered to me that we mustn't move too fast. Marlon looked magnificent. He was absolutely in top form. George and I froze on the stairs and suddenly Marlon looked up . . . and fell right over backwards. The intrusion on whatever was going on with him was so enormous that it literally knocked him right off his chair. Then he laughed.

I never got over my awe of Marlon during that whole period. He was the greatest star in the world and probably the most important actor. May still be. I had seen him in everything he'd done in New York, in Streetcar, in Candida, everything. I was just overwhelmed. Marlon knew that.

I was thirty-three. [Takes deep breath .] [On our way to Southeast Asia] we took a suite at the Plaza Hotel in New York, a three-bedroom suite with a huge living room. I was in my bedroom one night, trying to figure out some approach to this thing before we even got going so that I would have some fishing line to follow. It was snowing. I was standing there in my jockey shorts, letting the snow blow in the window all over me. I don't know what I was thinking of, but it was one of those mystical moments that people who are chronologically thirty-three, but feel about fourteen, go through. I was thinking, "God, this is the town I went to high school in. Where are all my high school friends? Where is everybody when I need them now? [In a mock tearful voice .] "Where's Mommy? Where's Daddy?"

Suddenly—I didn't even hear him come in—there was this arm around my shoulder. He said, without my having said anything, "You wouldn't be here if we didn't want you to be here. You wouldn't be here if we didn't need you here. You wouldn't be here if we didn't value you." Then he said, "I wouldn't be here if I didn't recognize that you and I came out of the same crucible of pain." Then he sat down and began telling me about his relationship with his mother, with his father, about his childhood. . . . He just made it so easy for me to be his friend. It set the tone for the whole next period, which was very difficult. Even to arrive at an airport with him took . . . It took six police cars to get him through the streets of Manila. The streets were packed; the airport looked like snow, there were so many white shirts that had been waiting there all night.

As time went on, I began to feel more and more as if I just didn't belong [in his company]. I was afraid I wouldn't find the story. I was so overcome by the responsibility of traveling with this guy. By having to hold up my end of the conversation every day for eight weeks. I was feeling less and less qualified as the minutes went by. Traveling around the world and comparing

myself with people I knew he knew. The writers I knew he knew . . . like Tennessee Williams.

What did you come up with, eventually, as a story?

We didn't come up with anything. I came up with a story which Marlon decided that he didn't want to do because it wasn't enough like an Alan Ladd film.

Meaning?

I don't know. He wanted a wide-shouldered adventure film, which none of us realized until he looked at the story I wrote. He never said anything about it all the time we were away together. I don't think that was the real reason. It was a time when he was turning everything down. Every piece of material was an enemy to him.

Because he didn't feel like working?

I don't think he really wanted to work. I think he's always had a tremendous conflict about that anyway. He has enormous regard for people who do useful things in the world. He thinks in some part of his soul that acting is silly. He has a kind of contempt for it. He considers it game-playing and trickery. I've never really heard him speak of an actor with any kind of respect or disrespect. I've never really heard him discuss acting . . . and never his own acting, except in a very jokey way. Delighting in all the tricks he's pulled as an actor.

Brando is very literate, right?

Highly, highly well read and sophisticated. It's hard for him to read, too. He sort of has to read aloud to himself. And it's curious reading. It's all over the place, and it's very much in line with whatever the core sampling of his interest is at the moment. He's full of remarkable little-known facts. He's like an anthropologist.

What happened after he rejected the screenplay? Then you wrote another version and that became The Ugly American?

No, no. That was the end of it. The script was called "Tiger on a Kite" and it was never made. That was the funny thing, because three years later [the book of] The Ugly American came out and I was called by Universal to write it. I said, "Well, there's only one person who you should get to be the producer for this thing, George Englund." I told them about this whole experience and they laughed. They said, "Well, George Englund is the one we hired . . . and Marlon is interested in doing it too." But the fact that we had the experience of being together in Southeast Asia for those eight weeks, and noticing what we noticed, made it really unnecessary to go back and do research.

I read somewhere that Brando had to have such a specific idea of what The Ugly American [1963] would be like that he had George Englund read him the script line by line before he would agree to do the film .

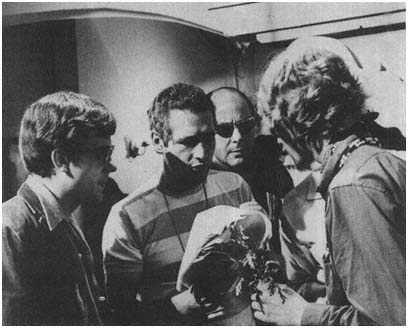

Stewart Stern (at right) with Marlon Brando and producer George Englund in Hong

Kong in 1956, searching for a story and forming the triumverate that went on to make

The Ugly American . (Courtesy of Stewart Stern)

There are probably pieces of truth in that story, and it probably didn't really happen that way. I think Marlon sometimes has to hear something and he has to read his own scripts aloud. He read me the movie he directed for Paramount [One-Eyed Jacks in 1961]; he read that whole thing aloud to me. Marlon fell asleep while he was reading his script to me—so did I. . . . Who knows why he would make George do that?

Was it your political outlook that informed The Ugly American script, or was it a story about the foolishness of the self-righteous?

That was what it was. The politics was as much an expression of that attitude as a painting is of the artist who paints it. We absolutely paint the world wrong, and when it doesn't correspond, we feel betrayed and act aggressively.

[Long silence.]

The reason why moviegoers felt that it didn't follow the book was because it didn't follow the book. I spent a long, long time writing a script that did follow the book—including the part about using bicycle power to pump water into the paddy fields.

George took the script to a village which we wanted to use, a wonderful village with terraced paddy fields. He sat down with the village elders and started explaining the story through the interpreter. Suddenly, all these mouths, which were red with betel juice, just broke into the most helpless laughter; they were falling all over in the dust at the notion of all these bicycles pedaling water straight up hill! First of all, the village spokesman said, "Do you know what it requires for us to be able to afford bicycles? And to have these bicycles being used as power to pump water? For centuries we've known that water comes down . . ." Then he showed us this elaborate, amazing series of aqueducts and bamboo sluiceways and water-powered wheels and things. The bicycle pump thing couldn't have worked at all on the scale described in the book.

So that was the springboard for you to rework the script?

That was the springboard for them to fire me. George felt that we had come to the end of a good try and that it simply hadn't worked. That we had been barking up the wrong tree. He thought we'd exhausted ourselves and that it would be good to get a clean start with somebody else. So, I was fired and I went and wrote The Outsider [1961]. David Zelag Goodman wrote another script for The Ugly American, which was not usable. Goodman was let go, as I had been before him, in the grand tradition of "blame the writer." George came to my office when I was doing my final rewrite on The Outsider and said, "You've got to come back." I said, "I can't come back. I won't come back. Impossible." He said, "Please, let's talk. You and I have a much more important story to tell than [Eugene] Burdick and [William J.] Lederer [co-authors of the bestselling novel The Ugly American ] did. We can use their characters. It's not about the rice fields, it's not about the bicycle pumps. It's not these people on the ground. It's what we do on a big scale, at the top."

So George had a series of ideas which was practically an outline. We sat down and worked on it and worked on it and worked on it, from scratch. George wasn't an official writer, but he contributed enormously and creatively to the story we finally told.

Was Brando a collaborative actor? Did he want to contribute to your script?

Not at the beginning. He was very concerned about the political balance. He did not want to have a script that was full of jingoism, except on the part of Joe Bing [the character of the U.S. public information officer in Sarkhan, played by Judson Pratt], who represented that attitude. But he wanted to be very, very careful about how the Soviet Union was portrayed and how the whole Cold War was treated. Especially when it came down to the relationship between Ambassador MacWhite [U.S. ambassador to Sarkhan] and Deong [a resistance fighter, played by Eiji Okada], his counterpart.

He also was inflamed about our own conduct overseas. I guess he felt more ashamed and infuriated by our clumsiness in a Third World society than any of [the rest of] us did. I think he's more sensitive. He noticed things. The smallest things would offend him deeply. On the most profound human level he would suffer if he saw acts of disregard, ones that could have been tiny and completely unconscious. It was really from watching Marlon respond, as much as from anything else, that I realized that the crime that could no longer be tolerated in the political arena was . . . our innocence. Which had once been so charming, the innocence of the "new" country, America. You couldn't be an innocent abroad any longer, there was no excuse for it.

At one point, Marlon finally approved the script. But what we'd find was that every morning on the set it would suddenly become his enemy, the way whole projects had become his enemy before. Except now he couldn't reject the project, because he was signed to do it and it was something that he had agreed to do. He had approved the script, he liked the scenes, he had worked on them, they all represented his input. Yet, when forced to confront a scene, to account for the fact that he might not have memorized it the night before, it became his enemy. So he would attack "it," in order, partly, to deflect attention from himself. Start blaming the script.

You must have felt extremely embattled .

It was very difficult. I was pretty rhino-hided by that time. It had happened to me so horribly before: those earliest moments in my career with Fred Zinnemann, who was my mentor and teacher and whose work I revered. I loved Marlon and I knew he loved me—it wasn't personal. I had seen him rage and blame, just hurl the blame around in a kind of mythic stance. He's Jovian when he flings the thunderbolts. You know part of it comes out of an easily offendable ethic and part of it comes out of simply not wanting to be caught doing something wrong. If he felt guilty about something, it was easier to attack everything around him than to face what he felt guilty about. Or to admit it.

One of the reasons that he and George Englund were friends was that George wouldn't accept this behavior. When Marlon would begin blaming George, George would just start laughing and say, "What are you feeling guilty about? Didn't you learn your lines? Is that what's going on?" They had a wonderful relationship, extremely trusting.

One day, we were supposed to film the confrontation scene between Marlon and Kukrit Pramjo, who played Kwen Sai, the prime minister of Sarkhan. Marlon looked at it and just thought that it was . . . terrible. He thought it was full of what he called "plot clinkers," those things you knock out of a pipe when the ash is dead and everything is hard. He said that's all it was, just a mess of plot clinkers. I said, "But you approved this scene. We worked on this. You said it was great and everything had been cured." He said, "Well, it hasn't. I looked at it again and it doesn't work."

Writers, well, a lot of us go on the assumption that if someone thinks what we write is bad, they might be right. So I was very sensitive to that, and he knew that too. Marlon used to say he could play me like a pipe organ. He just knew what valve to pull and what peddle to push and that he could get any sound out of me that he wanted to. I'm sure that he's right. And it's kind of fun to be played by a great player.

This was one of the key turning points of the film. I thought I had sort of covered over my own inefficiencies in that scene. But suddenly the radar was on it, and this thing that had been a friend to him was an enemy. And I realized that this time it was not to cover up anything that Marlon was guilty about. He was right, unquestionably right. And I didn't have a solution. He began challenging me, he began improvising as the ambassador. He would stand up in his dressing-room trailer and glare right in my eyes and demand to know what the Communists were doing up on the northern border. Challenge me to respond. Force me to be the prime minister. He was saying things like [in a loud, enraged shout ] "I don't care if I approved this scene before—I PISS ON IT!" And he would throw [the script] across the trailer. Then I would pick it up and throw it back.

The heat of it, the emotion of it, got us both screaming at each other. One or two very good lines passed our lips in the course of this that we then sat down and talked about. I wish I could remember the specifics of it. But something was generated in me that ideas began to come, that I felt this flush of emotion . . . that I had to write down. So, I went back and wrote a new scene—really a brand-new scene and brought it to him.

That didn't happen to me much on The Ugly American . It was an arm's-length film for me, it wasn't a revelation about some teenage boy who had problems. Marlon laughed the next day. He said, "Boy, to see you fight. I can't tell you what that meant to me. You got shoulders . It was wonderful to go head-to-head with you."

Had you ever had to defend your scripts in that manner before?

I had had to defend my scripts a lot. But I had never before let myself get that mad at somebody I needed that much.

A common thread in your films is that they could be extremely candid. Take, for example, the final scene of The Ugly American: While Marlon Brando as Ambassador MacWhite attempts, in an impassioned televised speech, to

right all the damage he has done, you have an apathetic viewer switch off the television set while he is mid-sentence. That scene displays a cynicism that must have been extremely rare in American films of that time .

For that scene, I had written a very long narration for Marlon that went on and on and on. To our amazement, he actually memorized it. I mean, we were thunderstruck. He hates to memorize things. He writes things on the inside of his hand, on the back of couches, has fake earphones so the dialogue can be pumped into his ear. It's partly, he feels that he wants to protect his own spontaneity. Like, in The Ugly American, he wore wax earplugs, and I didn't know why he wouldn't answer me when I would talk to him on the set. He wouldn't even see that it was me asking. One day he told me that he had plugged his ears with wax because the ambassador had to listen in a certain way; he had to listen as if through a wall . . . because he needed the information so badly. So Marlon will resort to anything.

About that [television] scene, I remember thinking, "We are sending this movie out and it will be perceived as a Marlon Brando movie, and nobody is going to give a shit about anything we're really trying to say, and say through him! [Begins to shout .] How could I tell the people of America that [Americans] don't give a shit . . . and that that is what is wrong?" That's how I got the idea of them not giving a shit and showing them to them . Maybe, in some indirect way, they would get the importance of what we were saying. Get it to step out of being a movie and get it to become their experience. That's how it occurred to me.

I remember going in to see Mel Tucker, who was the executive in charge of that film, and explaining to him what I wanted him to do. I thought it was amazingly courageous for the studio that was investing all this money in an uncertain project to put that ending on it. I never thought they'd buy it. I love that ending.

What was the official reaction from the U.S. government?

George Englund and I were denounced by Senator Fulbright, who stated in the Congressional Record, before he even read the script, that we were taking a very sensitive area of the world and turning it into an Elizabeth Taylor movie. She was never even considered for it.

There was a lot of animosity [towards the movie]. Also, the world hadn't caught up with what we knew. We were Cassandras then. No one from Hollywood knew that Laos was going to happen, that Vietnam was going to happen. We knew from our trip to Southeast Asia in connection with "Tiger on a Kite" that it was inevitable and that it would be worse. That it would go on and on and on until people finally got the message. Which Nicaragua proves perfectly that we haven't gotten. We will continue to mix around in other people's business because they're not like us . . . forever! Until finally we're taught a lesson.

Were your collaborations with Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman the most positive experiences you've had in writing screenplays?

They were very difficult. Never difficult with Joanne. But very difficult with Paul. Because of difficulty in communication. I tend to be very verbal. And Paul is minimalistic. Very often I won't get what he really means. Also, he is refined in a way that I'm not. He is selective in a way that I'm not. He refers to me as "baroque" and I refer to him as "linear Cleveland mind." To each other. I mean, that's how we talk to each other.

Are these difficulties over the script?

There were times on Rachel, Rachel, for example, both in the script and on the set, where he would feel things got too emotional or too overdramatized. That we didn't need it. He is very much in favor of the actor retelling an experience, so that we see the actor's experience through the actor's performance. Instead of showing it literally. He had a lot of resistance in that picture to showing Joanne making love with the character played by James Olson. When we got on the set, he didn't want to shoot it.

Because it was his wife?

I think that had something to do with it. But he didn't want excess. He thought things were much better left implied than stated. It informed the way he shot it. I saw it the other night again. It is the most beautiful sex scene I've ever seen on the screen. Because it's so implied, so discreet. It stays with her experience of . . . is she good enough? That's Paul's sensibility.

But he wasn't going to shoot the scene at all. [Editor] Dede Allen and I had to practically break his arm with the argument that it's better to shoot it and have it than to make that kind of decision on the set. Because he could always decide not to use it. So he agreed to shoot it. He agreed to shoot the embalming scene, where the character of young Rachel [played by Nell Potts, Newman and Woodward's daughter] goes in and sees the little boy being embalmed. I mean, we were all set up, the camera was there, and he didn't want to shoot it.

Because he felt the scene would be too disturbing for his young daughter to witness?

Yes. Once he saw what the scene looked like, he didn't want Nell to have to see it. He thought it would be too much for the audience, too.

What was it like trying to cope with Newman's sudden surges of protectiveness towards his family? Especially when it meant that your script would suffer as a result?

Very, very difficult. To try and maintain the friendship throughout was very difficult. There were times when we simply didn't talk to each other. Still, every day I was on the set. My obsessive watchfulness became a very heavy burden both for Paul and for Joanne. Finally, they had me sitting on a catwalk with a plank in front of me, looking through a knothole, so they couldn't see my expression. It bothered them that much.

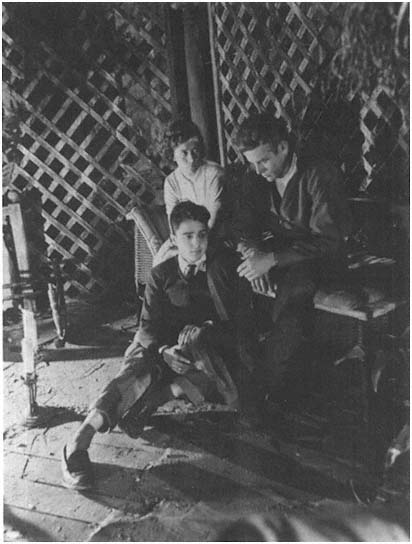

Stewart Stern (with dark glasses) being "helpful" on the set while Paul Newman

endeavors to direct Terry Kiser and Larry Fredericks in the Tabernacle scene

from Rachel, Rachel . (Photo: Muky, for Kayos Productions, Warner Brothers;

courtesy of Stewart Stern)

It begins to sound like a painful process of collaboration, for you, working with Newman .

Difficult, but rewarding. . . . When the Tabernacle scene took three days longer than Paul thought it would, and we wanted to catch the beginning of the changing of the leaves for the very last sequence, he told me to go out and storyboard the whole thing so that he could just come out [and film]. And I did. I did the whole sequence shot-for-shot and checked my directions with Dede Allen, making sure that I had people looking camera right and camera left when they should. I storyboarded the whole design of Rachel's walk through the countryside, after the kiss with Calla [Estelle Parsons], where the child flees and becomes Rachel, picking the flowers in the meadow. Long shot of Rachel walking down the hill, discovering the farm—all that, I designed entirely. And Paul Newman just simply filmed it, moving from location to location.

It was the kind of collaboration that could support that. We simply supported each other all the way through. By the last shot, we were short of equipment. The dolly and everything had had to go back because we were out

of money. Instead of a dolly, for the last shot, the cameraman sat in a Safeway supermarket basket and I pushed him. He had the camera between his knees.

You've continued to collaborate with them. You've recently completed a book-length account of twelve days of rehearsals of The Glass Menagerie, a production which Newman directed and Woodward starred in. And aren't you working on an authorized biography for Paul?

Well . . . I'm having a problem now with Paul, whom I've known for thirty-three years. He did ask me me to write his biography and, as well as I know him, I have real difficulty about making up my mind about the book. There's a lot I know simply as his friend that I don't want to talk about. There's a lot that I only suspect because he doesn't know himself that well. Which I could string together and make some kind of theory of and try to prove it. Probably three theories and take my choice, because there are so many streams in him.

Can you explain what you mean by that?

I can't really. He is so—not contradictory—it's just like streams, like four or five streams in him that run parallel and that never seem to cross. They appear and disappear; you see the shine and then it's gone. There's nothing, not an echo. Then there's a flash of light further on. You could put it all together and make a theory out of it, any one of these streams, saying, "This is the real Paul Newman." But I don't know. I wouldn't presume to do that. Even knowing him as long as I've known him.

Your relationship with Dennis Hopper has had similar ups and downs .

Dennis and I had such a love-hate relationship. It was a really painful time for me, the making of [The Last Movie ]. I have known Dennis since Rebel . He kind of hung around the Chateau Marmont. Paul and Joanne [Woodward] were staying there. And Tony Perkins. Jimmy Costigan, the writer. Warren Beatty, I think. We were friendly with Joan Collins, because she was going with Arthur [Loew]. We were always kind of together, either around the Chateau pool or up at Arthur's. Anyway, Dennis was one of the kids. And he and I got to be friendly after Jimmy [Dean] died. He fascinated me because he had ideas before anybody else did.

I always thought they were silly ideas. He would point out paintings that he thought were art, and I would get infuriated because the art seemed to have no history, tradition, background. I felt many of the artists that he was admiring seemed to come from nowhere. I felt they were sort of starting from each other. History was suddenly being looked upon with great contempt.

I feel it's important to have a sense of oneself as part of artistic continuity. It's the same thing that infuriates me when I go to the film department at a major university where they are giving out film degrees and no one has ever heard of Clifford Odets. To me, it's the Dark Ages. There's going to have to be a Renaissance where people again discover their own history. Film didn't begin with [Steven] Spielberg, you know. I just don't understand. It's a re-

markable lack of responsibility on the part of the educators. It's like giving degrees to people who can't spell. Suddenly, improvisation is supposed to be better than literature.

Is that what happened with The Last Movie?

I know that's what happened. That script wasn't taken out of my hands so much as put aside. It's still perfectly serviceable.

Were you on location while the movie was being shot?

No.

How did you discover that the script had, essentially, been discarded?

When I began reading articles, interviews with Dennis in which he said that there was no script and the [film] was all his idea . . . that he didn't need a script.

I wrote to him about it and told him that that was . . . not . . . accurate. Not an accurate representation. Later, he called me from Taos and said he was having trouble editing it, and would I come down there and help him? So I did. I went down and he ran all of the footage for me and for his agent at the time. We looked at film for about two days. Mainly, what I felt was very disappointed, not only that he didn't use the scenes as they were written in the screenplay and that he chose to improvise with people who were not up to that kind of improvisation, but also that he hadn't shot scenes that were essential. Including the ending of the picture.

Did you tell him that?

Well, I very strongly supported the idea of his going back and shooting the scenes as written. He wouldn't do it. Dennis and I have different opinions about the value of the movie he made. I think that he would have been much better off had he stayed with the screenplay. He acknowledges the value of the screenplay, but feels that that wasn't the picture that he had in mind then, and that he certainly isn't ashamed of having done what he did. I absolutely respect him for that.

Maybe you can still go back and do your version of The Last Movie, one of these days .

I suggested it. And Dennis thought it was not a bad idea. I said that we should double-feature them. Do the script. Cast it with somebody who should really play that stuff. Then show them as a double feature: The Last Movie and The Next Last Movie .

Despite your unhappy experience with The Last Movie, would you collaborate with Hopper again?

Anytime.

Do you feel that Dennis has grown as an artist since then?

Much. I think that what he has accomplished as a man in overcoming the habit, the addiction [to drugs], takes such courage. . . . You don't get addicted for no reason; you get addicted because it's the only possible way you can live your life. For him, without finding a way to live his life, to be able

to let go of that . . . to have that courage . . . was what changed him from what I felt was really a negative force, a dark spirit, into someone who can do enormous good.

To me, the performance in Hoosiers [1986] was the best that I've seen from Dennis. I long for Dennis to start dealing with the things that really, really have touched him. Kansas, the farm in Kansas, his grandparents. I always told him that I didn't know how deeply his connection to other people really ran. And that until he could really feel what they felt, he couldn't be an artist. I saw some of that in Hoosiers, a vulnerability. And I wish that he would let himself be moved again by his own childhood. There's a side of him which is authentic, and certainly much simpler than Robert Frost. That is absolutely American. Not just America at its hippest, but America at its most traditional.

Why did you decide to leave Hollywood, ultimately? Did you feel that those who run the New Hollywood are not people you can create for?

I didn't ever really come across the New Hollywood. The people who continued to offer me assignments were not New Hollywood. They were people who also felt besieged, or thought they were about to be. That's not why I left. I left because I just got . . . scared of the writing process. I seemed to have given over power to other people's minds. It's the thing I swore would never happen. The thing Clifford Odets once told me was the death of all writers. He said, "When you start seeing the other person's point of view, that's when you're in ultimate danger."

So your confidence was shattered?

It was assailed. I think as much from the inside as from the outside.

Producers and directors begin to tear down or diminish or reject ideas that are in the process of being born. . . . I'm talking about sitting in a story conference a third of the way into a screenplay, and when you venture a notion, it is cut off at the ankles—the pain of that, the insult, and I mean an insult that you physically feel [throughout] your whole system; because it's your offering, and it's not yet finished, and you're exposing it in the hope that the person you trust who is there to grow the project with you is going to be tender about it. When they're totalitarian, it breaks your bones. Rather than go through that pain, you shut down. You turn over the decisions. It got to the point where I was handing them my research and saying, "You check the margins and tell me what interests you." I got so fearful of offering ideas that I no longer even knew what ideas I had. I made myself available to absorb theirs.

So did your writer's block about screenwriting come from years of being abused at the hands of insensitive filmmakers, or did the rules in Hollywood change too much?

I think it was more of an internal announcement. One of the reasons I came

up here [to Seattle] was to see whether, without all of that outside pressure, I could originate something out of the soul as I once did before there was a job waiting. Of course, I immediately filled my time to the point that I haven't had the opportunity to face that, which is the thing I'm going to have to face. To just start with five-finger exercises. To see what it's like to put words together that I like to read. Or that feel good coming out. That come out bravely.

I look at my manuscripts, like Rebel . It was written in green ink on a legal pad. There's not a hesitation, not a correction. I look at the thing I did for [producer] Jerry Hellman, which was never made, a script called "Jessica," and the page is black with reconsiderations. You almost can't find your way from word to word because of the arrows and the balloons and the crossing-out on the page. That tells me something about what I'm allowing to come out. If it's so hard to permit something to see the light of day, it must be coming out in a terrible state of defensiveness. That's a cost that finally became unbearable to me.