Tephra Deposits Associated with Silicic Domes

Pyroclastic activity accompanies most phases of dome growth and is manifested as explosive activity. Newhall and Melson (1987) analyzed explosive activity during volcanic dome growth with respect to history, rate of growth and petrologic controls. Heiken and Wohletz (1987) reviewed dome-related tephra deposits and proposed four main types of eruptions (Fig. 5.6):

(1) Plinian and phreatomagmatic eruptions preceding dome growth,

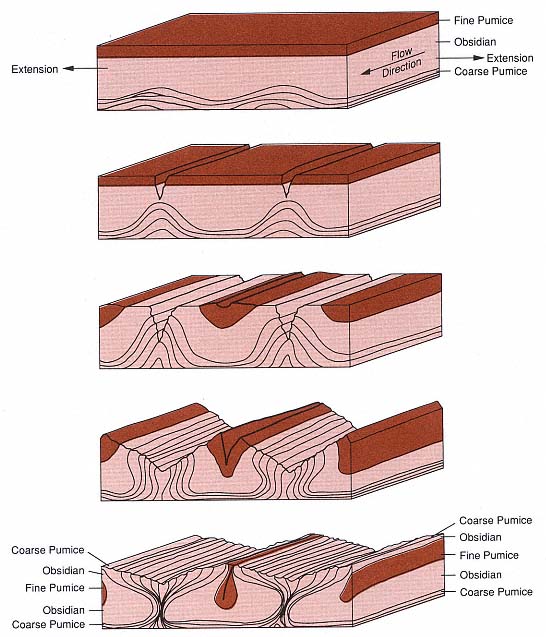

Fig. 5.3

Schematic diagram of lava foliation development. Successive block diagrams show the gradual rise of

coarse pumice diapirs while fractures propagate into the flow along the axes of flow and diapir

anticlines. Fink (1980b) reported that the diapirs form in response to a density inversion between

the relatively dense obsidian overlying the coarse pumice at the base of the flow.

(Adapted from Fink, 1983.)

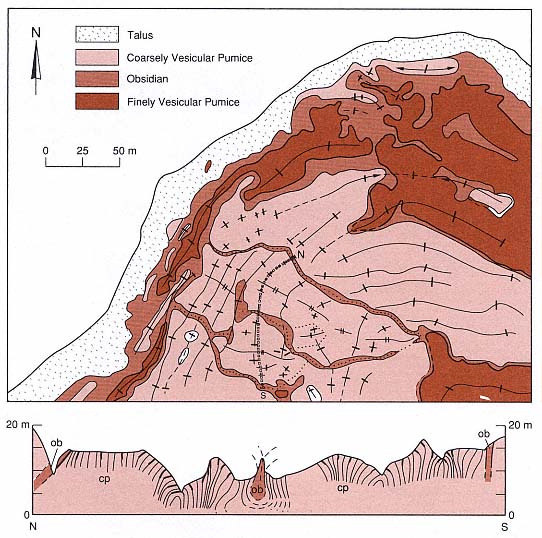

Fig. 5.4

Illustration of the surface geology of a rhyolite flow. This map depicts the northwestern lobe of

the Little Glass Mountain flow in northern California; the cross-sectional profile is from north to

south along the line

and the coarse pumice diapirs are denoted "cp."

(Adapted from Fink, 1983.)

(2) periodic Vulcanian explosions during dome growth,

(3) Peléean and Merapian activity resulting in dome destruction, and

(4) phreatic explosions during hydrothermal and fumarolic activity.

Table 5.3 summarizes the characteristics of tephra produced by these types of eruptions, and they are discussed in more detail here.

Initial Plinian and Phreatomagmatic Eruptions

Magmatic and hydromagmatic eruptions, which commonly herald new extrusions of dome lavas, create tuff rings and cones around vent craters. These eruptions follow depressurization of the gas-rich rising magma and its interaction with ground and surface water.

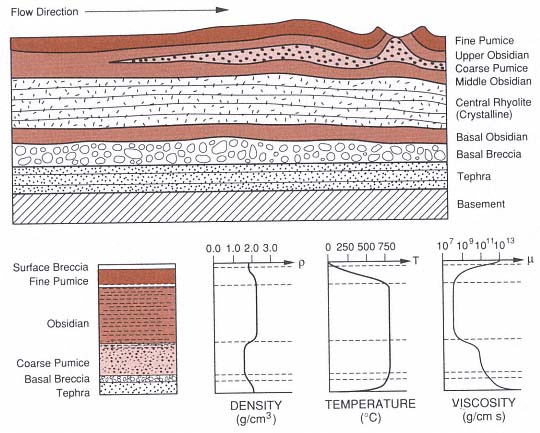

Fig. 5.5

Textural stratigraphy of dome lava. The cross section shows rhyolite lava-flow stratigraphy resulting

from the eruption scenario outlined in Fig. 5.1. The profile of density, based upon actual

measurements, shows an important density inversion at the top of the coarse pumice that

promotes coarse pumice diapirism. The temperature profile is calculated by conductive cooling,

assuming a constant internal temperature, and it shows a steep surface gradient that causes

fracturing. The viscosity profile is based on the laboratory measurements of Friedman et al . (1963).

(Adapted from Fink, 1983, and Fink and Manley, 1987.)

Figure 5.7 schematically illustrates tephra production that precedes dome formation. Magmatic eruptions produce pumice and ash deposits of a Plinian type, whereas phreatomagmatic (hydrovolcanic ) explosions result in fine-ash dispersal during pyroclastic surges and flows, which creates a tuff ring. Such eruptions usually produce most of the tephra associated with domes, but Heiken (1978b) found that their volume generally is relatively small (<0.1 km3 ) to moderate (1.0 km3 ). Near the vent, these tephra are well bedded and capped by lavas from the dome. Where the tephra extend several to tens of kilometers away from the vent, fallout layers are the most common expression.

Vulcanian Eruptive Cycles

Occurring during both growth and destructive phases of dome activity, Vulcanian eruptions tend to be periodic—especially where dome growth is prolonged by new magma

|

rising into previously constructed domes and plugs. Well-documented examples of such activity come from Soufriere of St. Vincent in the West Indies (Shepherd and Sigurdsson, 1982), and the type locality of the Fossa Cone on the Island of Vulcano, Italy (Frazzetta et al ., 1983). Typical tephra deposits consist of ash and lapilli falls, thinly bedded coarse and fine ash, dry and wet surge beds, and lahars. Distinctive of Vulcanian tephra are coarse ash deposits that contain blocky fragments of obsidian, older lavas, and poorly vesicular glass. Pumice fragments tend to be deposited during later stages of the eruptions when new magma reaches the surface and becomes highly vesicular. Most tephra erupted during Vulcanian dome destruction are those typical of hydrovolcanism (Fig. 5.8).

The cyclic activity of Vulcanian tephra production at domes is closely related to both the periodicity of magma rise within the volcano and vent-clearing explosions that provide a pathway for the new magma through older dome lavas. Such cycles are typical of composite cones in late stages of evolution (see Fig. 2.16) when sequences of wet, and then dry, hydrovolcanism are followed by magmatic pumice eruptions and finally by silicic lava emplacement. In areas of coalescing domes, such as ring fracture areas, the cycle may only occur once, leaving a blanket of tephra over older dome lavas.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Peléean and Merapian Dome Destruction

Tephra deposits found on the flanks of silicic domes developed from disintegration of the extruded lava either closely following or years after its extrusion (Peléean and Merapian, respectively). Such deposits consist of poorly vesicular lithic pyroclasts that were derived from partly to completely solidified lavas emplaced as block and ash flows. Some examples of these products are provided by the 1902 eruption of Mont Pelée, Martinique (Fisher and Heiken, 1982) and the block and ash flows of the 1930 dome collapse at Merapi, Java (Neumann van Padang, 1931). Figure 5.9 illustrates two types of dome destruction, both of which began with the brittle failure of lava. At Mont Pelée, the recently extruded lava spine was apparently highly charged with gas trapped in vesicles; when the lava crumbled, the vesicles violently discharged gas—and thus drove the comminution of the lava. At Santiaguito dome in Guatemala, the front of a silicic lava flow collapsed and disintegrated into a pyroclastic flow because of trapped gases (Rose et al ., 1976). The mechanical strength of the lava can degrade, which produces explosions; this situation is often connected to fumarolic activity. Hydrothermally altered lithic fragments are common in tephra of Peléean and Merapian activity.

Phreatic Eruptions

Phreatic explosions usually produce craters in the vent and fumarolic areas of silicic domes and lava flows. They also produce mantling layers of fine-grained tephra, explosion breccias, and small tuff rings and cones. Although phreatic tephra do not generally contain juvenile components, it is understood that phreatic activity can be a precursor to magmatic eruptions, as is shown in Fig. 5.10. The tephra most frequently associated with favorable geothermal prospects in domes are accidental lithic fragments that are strongly

Fig. 5.6

Stratigraphic relations of dome tephra. Four principal occurrences are schematically illustrated:

(a) Plinian and phreatomagmatic eruptions of tuff rings and cones (shown with overflowing lava

plug), (b) coalescing domes with phreatic and phreatomagmatic carapaces, (c) Plinian, far-field

pumice falls and flows, and (d) Peléean avalanches and Vulcanian intercalated tephra (flank

deposits) at polygenetic domes and composite cones.

(Adapted from Heiken and Wohletz, 1987.)

Fig. 5.7

Schematic illustration of initial Plinian

and phreatomagmatic eruptions

(a) in an initial Plinian stage and

(b) followed by phreatomagmatic explosions.

(Adapted from Heiken and Wohletz, 1987.)

altered and coated with clays. In many cases, phreatic tephra deposits are limited to areas where strong hydrothermal activity has led to a build-up of high-pressure steam below or within a sealed caprock. Failure of the caprock results in steam explosions and the formation of phreatic pits and ejecta layers.

Hydrothermal systems associated with silicic domes take on configurations that are controlled by dome stratigraphy and structure as well as the structural setting of the region. Even though the heat contained in dome lavas may be relatively insignificant, that provided by an underlying differentiated intrusion can drive hydrothermal convection if sufficient water is present. Because water is a fundamental component of eruptions of silicic domes, in this chapter we will reiterate its function and expression in eruption phenomena and then illustrate its subsequent hydrothermal behavior through hypothetical models.