Preferred Citation: Davis, Whitney. Masking the Blow: The Scene of Representation in Late Prehistoric Egyptian Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft7j49p1sp/

| Masking the BlowThe Scene of Representation in Late Prehistoric Egyptian ArtWhitney DavisUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1992 The Regents of the University of California |

For Alexander Marshack, and his questions

Preferred Citation: Davis, Whitney. Masking the Blow: The Scene of Representation in Late Prehistoric Egyptian Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft7j49p1sp/

For Alexander Marshack, and his questions

Preface

In this book I interpret a group of late prehistoric Egyptian representations that deserve to be more widely known among art historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists. While writing it I have been thinking of artifacts and images from other cultures—Upper Paleolithic engravings; rock art of the Tassili Mountains, Arnhem Land, or the Brandberg; "animal-style" art from Luristan to Scythia and beyond; the paintings of the Catacombs; late antique ivories; Celtic metalwork; the rock-cut signs of Bronze Age Scandinavia; Viking woodwork; Navaho sand painting; and modern urban graffiti. If art historians convert these artifacts into pure images, archaeologists convert the images into pure artifacts. Both art historians and archaeologists who think anthropologically or historically take the artifact-signs as complete in themselves. Anthropology and history want them to be indexical, iconic, or symbolic wholes and stylistic, functional, or ideological markers—objects in which artifact and representation somehow coalesce without remainder or disruption—rather than made things, elements in a chain of replications, and complex, always incomplete, mediations of intentionality.

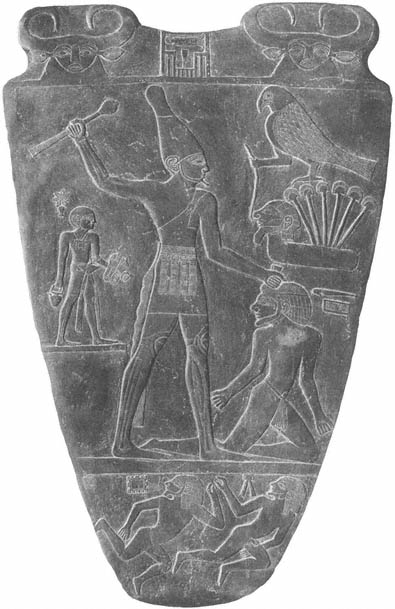

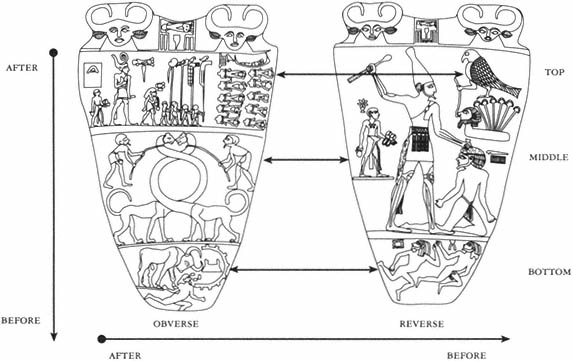

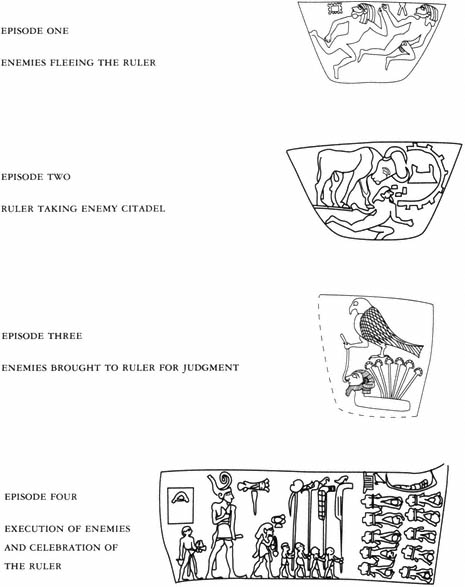

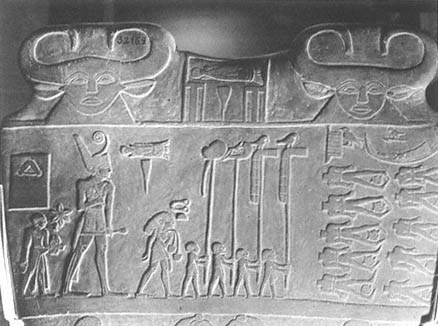

I have kept examples other than the late prehistoric Egyptian—they could be unlimited—out of the way and discuss the larger issues briefly. The few objects I have chosen to discuss have undergone exhaustive reinvestigation. For example, to my knowledge no earlier commentator had noted the substantial recutting on the Narmer Palette—not modern alteration but a telling sequence of revisions and slips in the "original" making.

The plan of the book is straightforward. Chapter 1 introduces the problems and possibilities of an interpretive history of late prehistoric Egyptian representation, considering both the evidence and some aspects of historical and critical

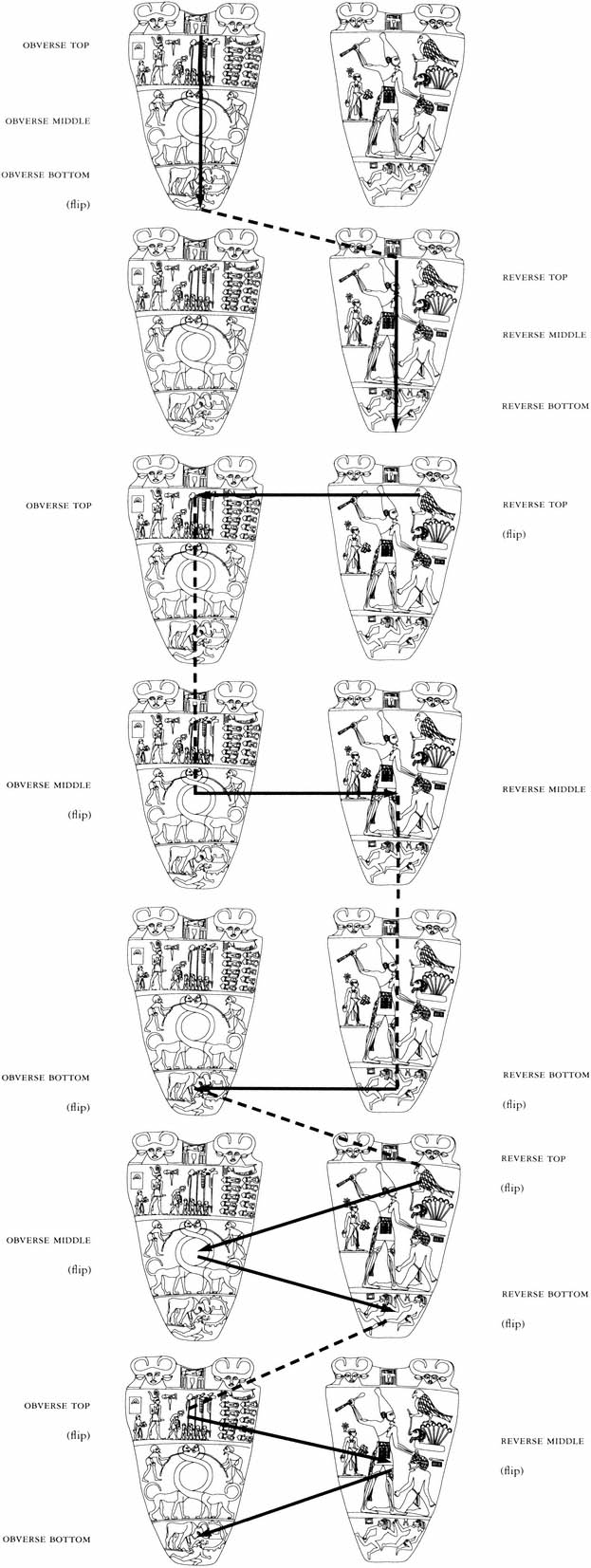

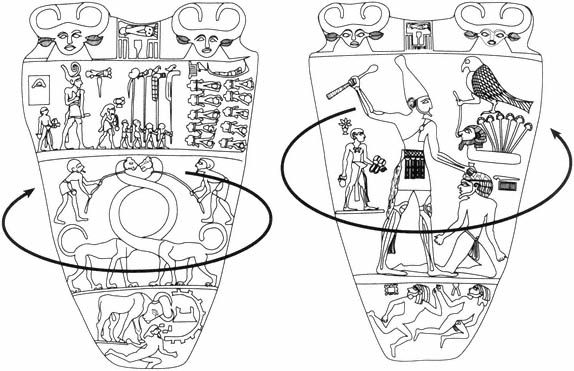

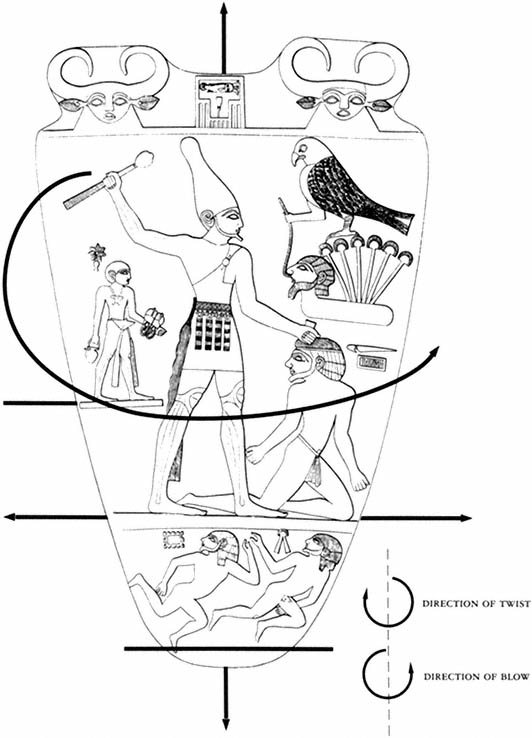

method. I note questions of theory as such—for example, the more or less intractable issue of intentionality in the replication of artifacts or images. And I provide information about the date, archaeological context, and function of the objects. Chapters 2–7 interpret a series of late prehistoric images produced about 3300–3000 B.C. , before the emergence of the dynastic state in ancient Egypt with its tradition of official, or canonical, image making. I recommend that readers study the illustrations before reading through my discussions; although I do describe the images, my remarks assume familiarity with what can be seen, and, because the images are complex, some elements of the analysis may be hard to follow without reference to them. Chapters 8 and 9 consider one object, the so-called Narmer Palette, frequently regarded as standing at the beginning of the canonical tradition, about 3000 B.C . Within Egyptology there is a consensus—an important but problematic one—that the Narmer Palette represents a new departure for Egyptian image making. Although I want to be cautious about this point of view, I believe the Narmer Palette requires a detailed, independent assessment; furthermore, in my treatment of it I investigate some questions that I do not address for the images considered earlier in the text.

Finally, in the Appendix, I outline my approach to pictorial narrative, the most immediate background—although not the only background—needed to understand the nuts and bolts of my particular reading of late prehistoric Egyptian images. This discussion considers the ladder used to reach a certain level of substantive analysis—a ladder that can be thrown away once that level is attained. But prehistorians and Egyptologists may well ask about the basis on which I have put forward the substantive account. Since historical or archaeological confirmation for any interpretation of late prehistoric Egyptian art is sketchy at best, an evaluation of my account will depend partly on the theoretical and methodological grounds—on theoretical consistency, for example—discussed in the Appendix. And because my approach to pictorial narrative differs from those of others who have written on prehistoric and Egyptian art, the Appendix also defines my terms and sets out my response to related issues.

One general remark about procedures is in order here. In the broadest sense this book is about the positions people have in, and in relation to, representation. Where the gender of these people is known—for example, the enemies of

the ruler in several of the images are explicitly depicted as male—I specify it. Otherwise, I tend to use the masculine pronoun in description; in fact, it turns out, no women are directly depicted in any of the images. (I use neuter forms for animals to leave the question open; although there are gender distinctions marked by, and therefore possibly wrapped up in, the metaphorical and narrative structures of the animal images, I have been unable to make much sense of them.) But I occasionally break away from this practice when it is worth recalling that the gender of the most important identities in my story—the ruler, the artist, the viewer—is often not known and probably included women. For example, the ruler figured in the images could be—the possibilities are not exhaustive or mutually exclusive—father, mother, hunter, warrior, shaman, matriarch, headman, king, or queen. Viewers of either gender could have occupied, imagined, or identified with these positions, although probably in different ways. Parallel considerations apply to ethnic or racial identity. In some cases the viewer of an image may have had the same ethnic origin as the "enemy" depicted in it. Someone identifying with the position of the "ruler" who did not share the ruler's depicted ethnic identity—in one image he is depicted as an Upper Egyptian—would presumably have had an experience of the image different from that of someone who shared this identity. And so forth; again, I leave the question open where possible.

Curators in Egypt, Europe, and America have kindly allowed me to examine objects in their care, often at very close quarters, and have provided photographs, while several scholars have allowed me to use their drawings of particular images. Individual acknowledgments are rendered in the illustration captions. The artist who prepared the diagrams for this publication, Jandos Rothstein, deserves special credit for his patience and care. Research and travel for the initial draft, completed in 1988 and 1989, were supported by a grant from the Office of Research and Sponsored Projects of Northwestern University. I owe special thanks to Wolfgang Kemp, a faculty member at the Institute for Theory and Interpretation in the Visual Arts sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities at the University of Rochester in 1989, for piquing my interest in such black holes of art history as constitutive blanks and imaginary artifacts. Students in two graduate seminars at Northwestern, especially

Laura Weigert, have helped me to develop my analysis. Two anonymous readers for the University of California Press and the art historians Robert S. Bianchi, Celeste Connor, and James Marrow provided detailed comments that have helped to shape the final draft, completed with the support of a Humanities Research Award from Northwestern University for 1989–90. Throughout the process of turning a briefer presentation of some ideas into a complete monograph, it has been a pleasure to work with Deborah Kirshman and her colleagues at the press.

Alexander Marshack has been asking questions that I am not sure any archaeology or art history could answer, and I am not sure he would be satisfied with what I offer here. But I cannot imagine this book without the example of his work on prehistoric marking and symbolic systems. I am delighted to dedicate it to him.

WD, MAY 1992

Chronological Table

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1—

History and the Scene of Representation

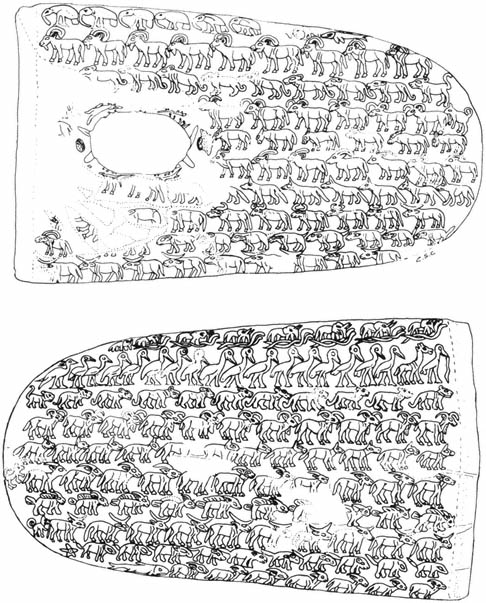

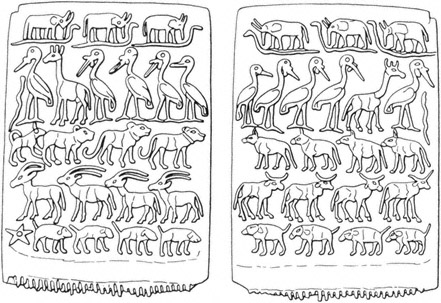

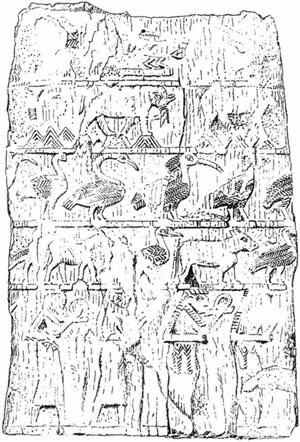

The register ground line is the most important compositional device of Egyptian canonical representation, the official image-making tradition of the ancient Egyptian state from its establishment about 3000 B.C. until its dissolution in the Hellenistic and Roman periods (Figs. 1, 2). The ground line holds animal or human figures apart. It orders and fixes them, possibly overlapping them slightly, in isocephalous rows. Finally, it orients them in a consistent direction, often toward a figure of authority also depicted in the image—if not always in the same register—and generally the patron of the work, who takes possession of them as his estate.

Register, Composition, Image

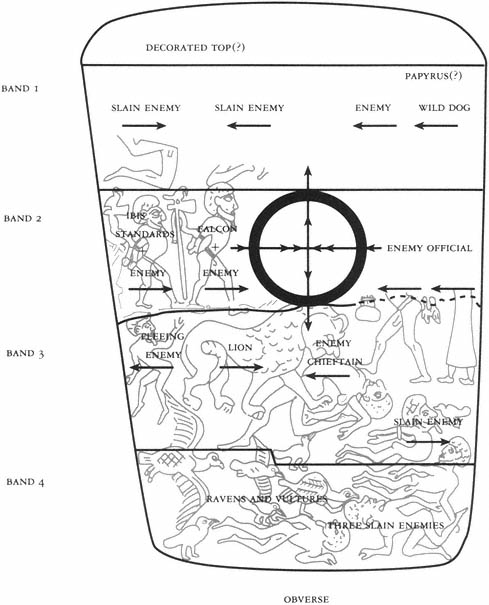

Although the register ground line is a compositional device, it does not necessarily delimit the image, understood, as it is throughout this study, as a pictorial statement of an often complex reference using a variety of available "textual" resources like narrative and metaphor. For example, an individual register might frame a group of animal or human figures, but often the action of these figures and the "meaning" of the group cannot be understood without referring to an official, monarch, or divinity depicted not in that band but rather elsewhere in the image. Register bands frame elements of an image—namely, those that are literally depicted on and by the surface of the pictorial medium as it has been cut up and organized. The elements of a literal depiction in any particular passage of an image, however, are not necessarily the same thing as the image itself, the semiotic whole that functions as a narrative or other kind of sign.

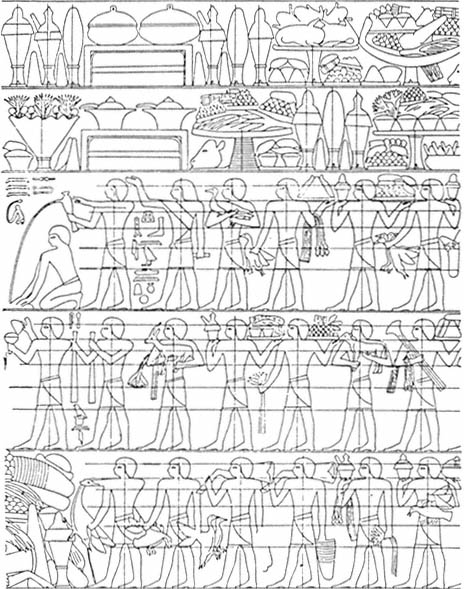

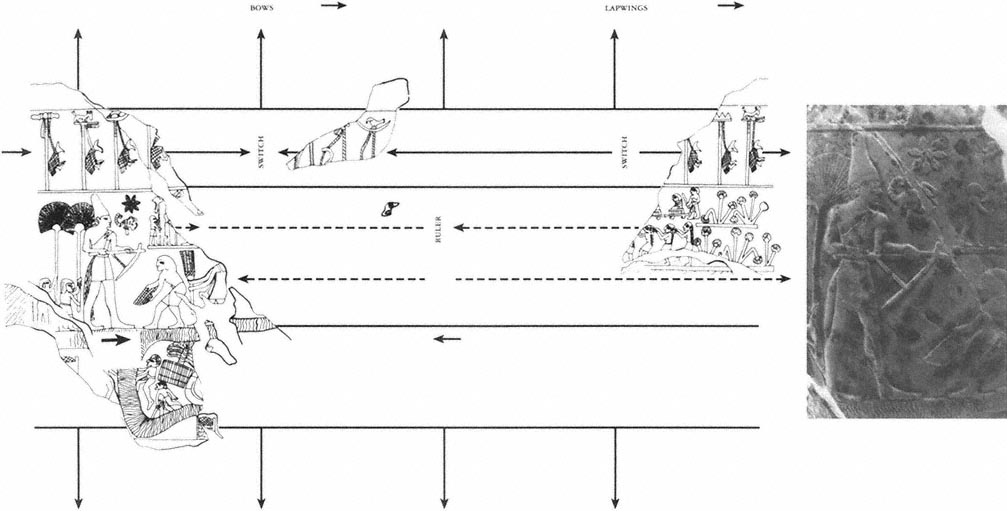

Fig. 1.

Principles of compositional organization in canonical Egyptian art, illustrated by unfinished

painted relief, tomb of Perneb, Old Kingdom. After Williams 1932.

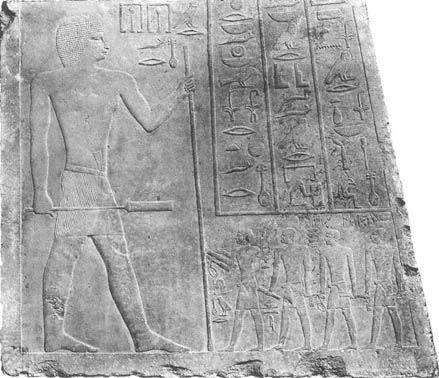

Fig. 2.

Tomb relief, exterior wall of tomb of Nofer, Old Kingdom.

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

As a compositional device a register might not only frame but also organize an image consisting of several discrete passages of depiction, or "pictorial text." The great painted caves of the Magdalenian period in Upper Paleolithic southwestern Europe, about 15,000 B.C ., provide instructive examples of the relations between composed passages of depiction and the image as a totality (see Leroi-Gourhan 1967, 1986). The caves sometimes contain thousands of figures organized in distinguishable compositions or passages of pictorial text on separate "panels." Nevertheless, each cave might amount to a single complex image, perhaps a narrative or other kind of semiotic structure making use of textual modalities other than depiction (see Vialou 1981, 1982). This image would necessarily be taken in by a viewer in a drawn-out act of viewing that

includes several techniques of "reading." (Conceivably the act of making extended over a considerable time as well; see Marshack 1977.) Even on a tiny object—like the decorated combs and cosmetic palettes we are examining here—the smallest passage of pictorial text, apparently bounded by a framing device that might simply be the edge of the object itself, can be organized internally as an image or images. In sum: composition is the organization of depiction, both within and among its divisions or frames; passages of depiction present—are the "text" of—the image; and the image is the concatenation of passages of depiction functioning as a referential whole for a viewer.

In the Egyptian canonical tradition image makers generally used several registers to organize an image. Composition therefore takes place both within registers—obeying the separateness, the isocephaly, and the constancy of direction of figures, among other criteria (see also Davis 1989: 29–37)—and between registers as they are arrayed on the surface of a wall, within the larger architectural setting, and even within the context of an entire building, building complex, site, or territory (see Tefnin 1979, 1981, and 1983 for fundamental considerations). Figures, registers, and images tend to be organized hierarchically with no extraneous or competing pictorial matter. They can be accompanied by hieroglyphic texts, rebuslike signs, and other symbols that perform complementary, parallel, or identical referential operations (Fischer 1986), with "picture" and "hieroglyph" often working together to constitute the "image." In the canonical tradition an entire decorated object or monument—an item or suite of furniture, a three-dimensional sculpture with applied depictions in relief and incised hieroglyphs, a painted tomb chapel, or a temple—sometimes functions as a single image. Whatever its configuration, this image was taken in by a viewer in a complex, hierarchically organized act of viewing governed by social realities and conventions. For instance, not every viewer could "read" all passages of the pictorial text: some were presented in hieroglyphic writing incomprehensible to many viewers, and some were sacred precincts visited only by the specially qualified. Nonetheless, however complicated it may be as a physical entity, the object or monument presents a reference that was legible in part or as a whole to a few or to many viewers as that reference.

As this description implies, the canonical Egyptian image is an intricate affair. In the real space before the decorated wall, the artist, the official or royal patron, and other viewers face the register band at right angles to the direction of movement of its depicted figures. Human figures within the band are depicted not in absolute profile but in the well-known "frontal/profile" aspect (Davis 1989: 27–29). When reversal of the orientation of figures, detachment of figures from the ground line, and so forth, occur in Egyptian canonical representation, it is because every scene was designed to fit a specific architectural context, and the patron's individual requirements for story and symbol had to be met. But every figure has a "space" where it stands out from the ground of the image in a clear silhouette (see also Groenewegen-Frankfort 1951; Smith 1965; Schäfer 1974; Davis 1989: 7–37, with full references).

Late Prehistoric Images

These features of register composition cannot be assumed to have been present in the same way in Egyptian image making before the consolidation of canonical conventions, a process that began in the early First Dynasty and was apparently not completed until the Third (Davis 1989: 116–19). For example, in prehistoric or early dynastic image making the viewer's line of sight might not have been fixed, by the way figures and composition are constructed, at exact right angles to the line of movement of the figures depicted within the image. If the perspective for the viewer of a precanonical image was different in relation to the figures depicted from that of the viewer of the canonical image, despite continuities between them in the technique of rendering individual figures, the two types of image could have been based on different pictorial principles. It is on the basis of such differences, in fact, that we must distinguish canonical and noncanonical image making in the first place.

The essential point is to avoid assuming that the works under discussion function as images exactly as do canonical images. Hence I avoid labels that would associate them with canonical images, if only as their predecessors. Both types of image have an intricate structure, an often highly ingenious means of setting up figures and compositions in organizing a passage of depictive text.

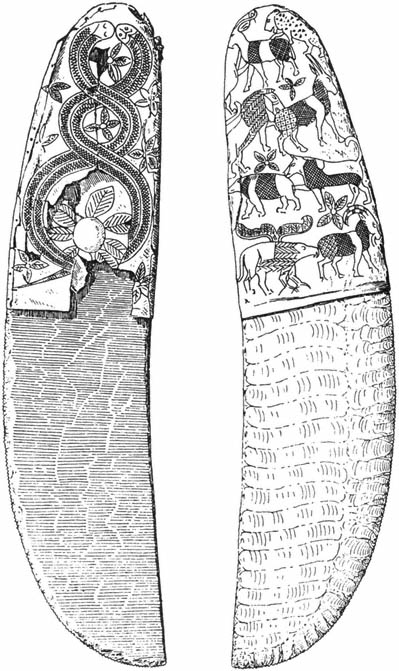

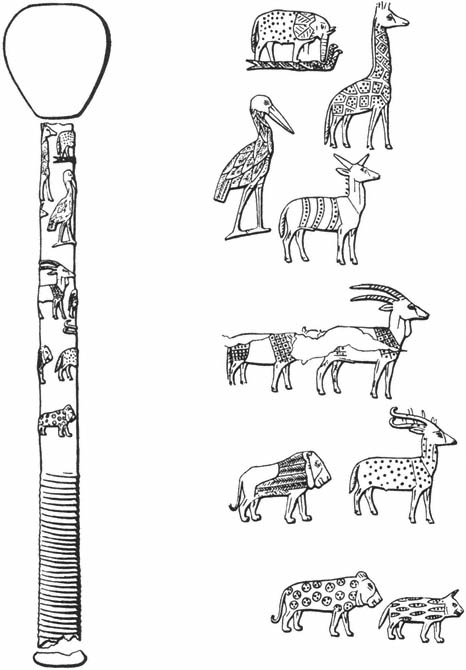

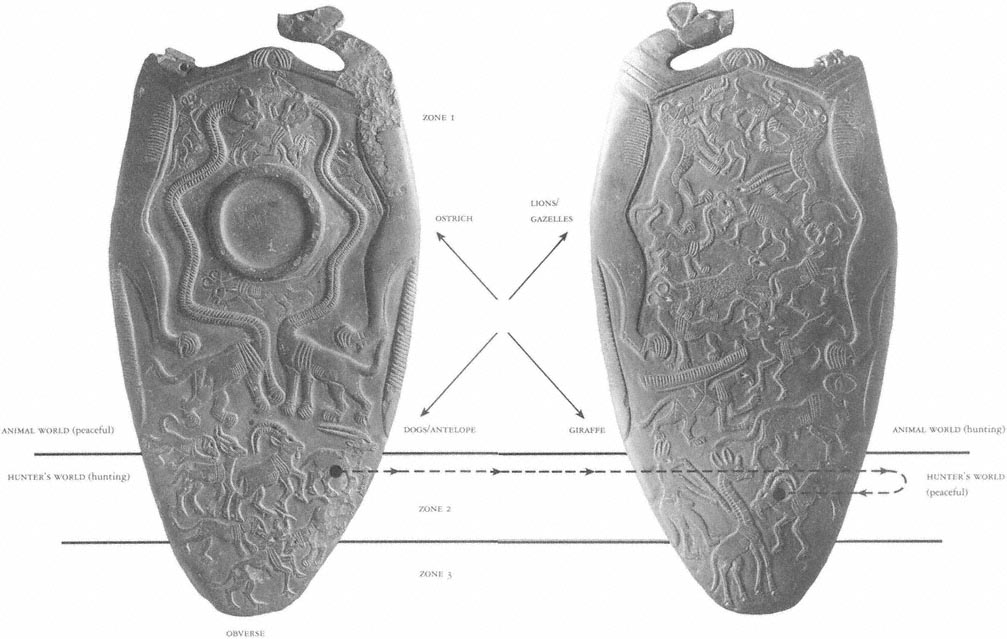

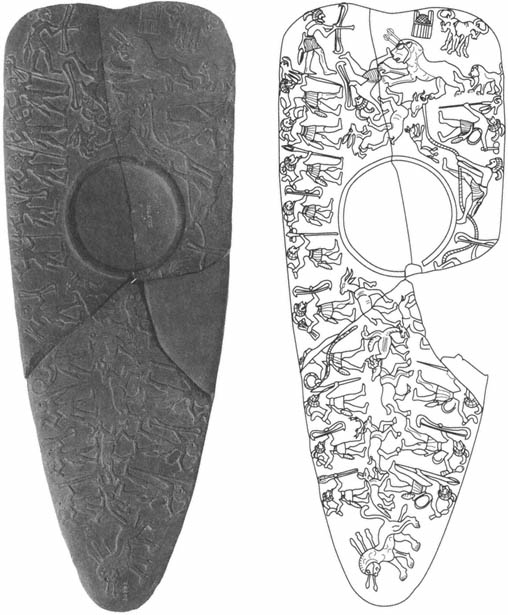

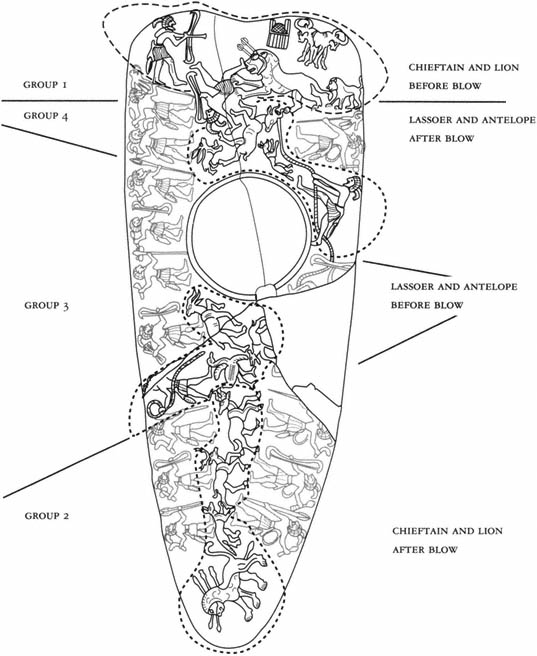

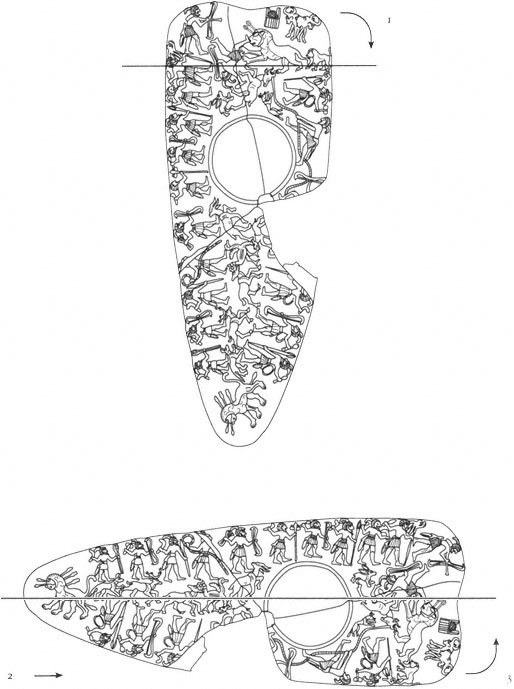

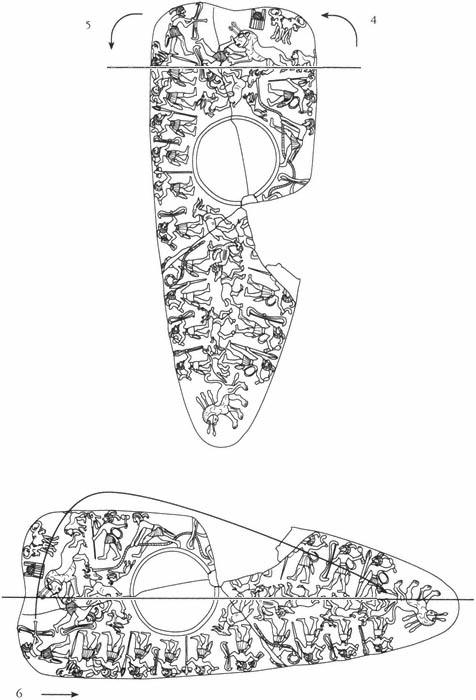

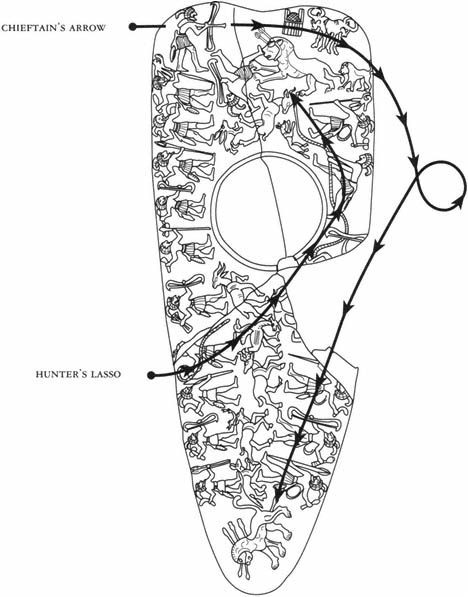

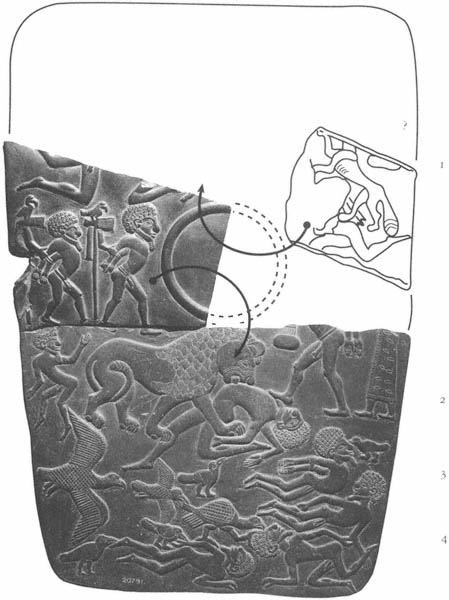

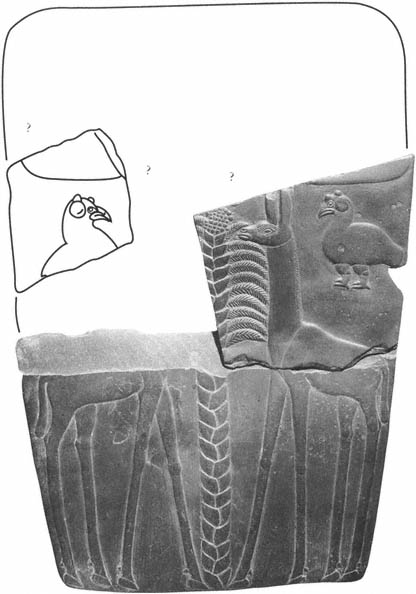

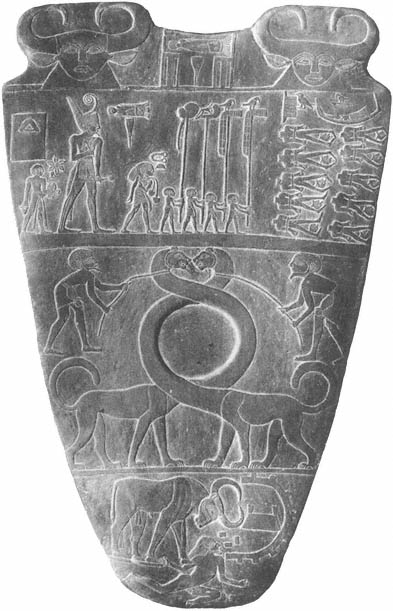

In investigating the nature of noncanonical image making, I look here at the emergence of the canonical register ground line in six major works of the "earliest"—or what I call late prehistoric —Egyptian art (late predynastic, proto-dynastic, and very early dynastic): the Brooklyn and Carnarvon carved-ivory knife handles and the Oxford, Hunter's, Battlefield, and Narmer carved-schist cosmetic palettes. My reasons for preferring the unfamiliar historical designation "late prehistoric" for these objects will become increasingly obvious as we consider in detail how they should be characterized. In general, the term is useful not least because it is slightly paradoxical. On the one hand, it is illuminating to look at the images from the vantage point of later canonical art, so long as we avoid anachronism. For example, when examining the selective conventionalization of an inherited prehistoric visual culture by artists of the later dynastic or canonical tradition (Davis 1989: 116–91), it is acceptable to label objects as "predynastic" (Williams and Logan 1987), "precanonical" (Davis 1989), or "Preformal" (Kemp 1989) because we are considering the images only as they were viewed by later viewers . But on the other hand, if we are looking at the images from the vantage point of the immediate world in which they were first made to make sense, then teleological and possibly anachronistic labels like "predynastic" are misleading. Within the so-called predynastic period, no artist or viewer could have been self-described as "predynastic," "precanonical," or "Preformal," although he or she certainly did belong to an earlier tradition and may even have had a firm sense of his or her "late" or "latest" position within it. Although no general label suits all purposes, we should seek to use a term representing the real position of the works in the replicatory sequence to which they belonged. A word like "protodynastic" might capture some of the nuances, especially for transitional works like the Narmer Palette (Chapters 8, 9), but it lacks one usual connotation of "prehistoric"—designating society without script—that is important to preserve in relation to the images considered in this book. While I do not focus on the topic as such, I believe late prehistoric images to be intimately implicated in the development of Egyptian hieroglyphic script itself. They are the "writing" that precedes the appearance of a secondary transcription system, the writing of writing, in hieroglyphic script.[1]

Where appropriate I refer to existing interpretations of particular works by writers like Georges Bénédite (1916, 1918), one of the first to study the images

systematically, or by Helene J. Kantor (1944) and Elise J. Baumgartel (1960), among the first to make use of archaeological evidence in interpreting them. I cite also the iconographical or more broadly iconological speculations of Egyptologists and prehistorians like Henri Asselberghs (1961), Michael Hoffman (1979), Elizabeth Finkenstaedt (1984), Bruce Williams (1988a), Bruce Williams and Thomas Logan (1987), and Barry Kemp (1989). I do not, however, take up every point of agreement or disagreement with all these writers. Except for a pioneering structural analysis of the Hunter's Palette by Roland Tefnin (1979), most available accounts of late prehistoric image making merely list the various figures or motifs, make iconographical comparisons, or offer generalized remarks about the apparent themes of individual passages of depiction. (Williams [1988a] analyzes what he calls the "structural logic" of late prehistoric representation, but he does not employ accepted iconographical, structuralist, or semiological procedures in his descriptive-comparative compilation of similarities among motifs and their supposed "meanings.") By contrast, my principal goal is to account consistently for many features of the images, including some of the most striking, that have remained unexplicated, misunderstood, or even unnoticed.

The task of identifying late prehistoric images as such—getting beyond existing descriptions of motif, composition, and passages of depiction to discover their referential coherence as images—is more difficult than it looks. Although the objects have been the focus of a good deal of writing already (see, for example, Hoffman 1979; Finkenstaedt 1984; Kemp 1989) and have played a major role in the general interpretation of Egyptian art, I believe that their pictorial dynamics have not been completely appreciated.

A part of my purpose is to supplement a brief commentary on the images offered in a study of the canonical tradition in Egyptian art (Davis 1989: 136–71). In that account I was interested in late prehistoric objects for what they can tell us about the origins of later Egyptian artistic conventions. For example, we can understand canonical Egyptian art better if we know that its conventions for rendering the overall aspect of the human figure were deeply rooted in multifarious ancient visual contexts, dating as far back as the fourth and fifth millennia B.C ., while the conventions for the proportions of the figure were of relatively recent vintage and had developed in one particular context at

the end of the fourth millennium B.C . Such information suggests that although the canonical artists and patrons made use of—took account of and made reference to—a widely accepted and historically diffused image of the human body, they also reconfigured that image, grafting onto it new formal features and presumably revising its connotations as they had been inherited. Although throughout my earlier analysis I insisted on the non- or precanonical status of prehistoric and predynastic images in relation to the later canonical tradition—they are good examples of what Barry Kemp (1989) calls the "Preformal" tradition always characteristic of some levels of or moments in Egyptian society—I did not consider late prehistoric images in their own terms.

In this book I reverse the emphasis of my earlier approach. Instead of examining the long-term dynamics of a complex, mostly literate tradition, looking at individual images only insofar as they might exemplify general aspects of that tradition, I consider a few images in detail. Partly because the issue has been treated comprehensively by other writers, I do not concern myself too much about their place, noncanonical and canonical, in the larger prehistoric and dynastic traditions, except in one case, that of the Narmer Palette (Chapters 8, 9), where the issue is especially pressing. By definition such a close focus has disadvantages in not considering the sources for late prehistoric representation. Even this disadvantage, however, may be more apparent than real. As we will see, a rigorous distinction should be drawn between the sources for a motif and its "meaning" as used in a particular pictorial text—for example, as a metaphor or a narrative. That we can identify sources for motifs says nothing about their metaphorical or narrative status in particular contexts. For instance, allegorical uses of a motif in continuous replication can take over what had once been narrative uses. If we studied only the continuous development or "transmission" of the motif in or as a stable formal tradition without investigating the "disjunctiveness" of its meaning (Panofsky 1960) as the very condition sustaining that tradition, we would miss entirely such semantic possibilities as metaphor and probably misconstrue the coherence of the tradition as such. A full consideration of the chain of replications, the "tradition," of late prehistoric image making (Chapters 2–6) will enable us to interpret the iconography in a single image belonging to that tradition and sustained disjunctively by revision into new formats and new contexts (Chapters 7–9).

Sequence, Date, Context

The study of late prehistoric representation in the Nile valley is extremely limited in the archaeological evidence to which it can appeal. Unlike works of later Egyptian art, often closely dated and associated with known historical personalities, events, or institutions—like a particular official's ambitions, the cult of a particular temple, or the building projects of a particular monarch—the late prehistoric works cannot usually be fitted into an informative historical context. Even if they have been excavated, the assemblage or site from which they derive is often puzzling.

Objects that lack archaeological provenance altogether have been acquired on the market in the final years of the last century or have turned up periodically since then. Art historians and archaeologists are often inclined to fit such un-provenanced objects into the overall picture of late prehistoric art in Egypt, for example, by making detailed technical and stylistic comparisons that associate unprovenanced with dated specimens on various grounds of morphological similarity (Fischer 1958; and Davis 1981b, 1989: 155–59 are examples of such efforts). Studies of this kind have limited value, however, especially if they examine objects outside the canonical context, in which the forms and meanings of images are likely to vary more than in the canonical tradition. In principle morphological similarity of mannerisms and motifs among a group of objects says nothing about the way in which a mannerism or a motif was used in a specific context in a particular image. Thus the chronological or cultural contiguity of images can be demonstrated only by showing that they are similar both in their technical and stylistic morphology and in their pictorial mechanics and metaphorics. Of several unprovenanced objects thought to be late prehistoric in date, the Oxford, Hunter's, Battlefield, and (to a lesser extent) Narmer Palettes seem to be similar in these latter respects. Therefore they can be regarded as belonging to the same evolving cultural tradition, a coherent series of making reference or what I call a "chain of replications." Furthermore, other unprovenanced objects fall outside this chain of replications because they violate some or all of what I call its general conditions of intelligibility (Chapter 7). I have almost no doubt that some of these pieces are modern imitations; they were manufactured by forgers who had seen the morphology but did not com-

prehend the pictorial structure of known works of early Egyptian art. To understand the mechanics and metaphorics of such images, as I am attempting here, is to establish a foundation for clarifying the forgery of early Egyptian art—making possible a study that is yet to be written.[2] Other unprovenanced pieces may not be modern forgeries but probably belong to different, if contemporary, chains of replication in late prehistoric art—for example, a chain of replications influenced if not actually produced by foreign craftsmen that is somewhat independent of the series being considered here.

A few sources of documentation help with the preliminary business of dating. The decorated, frequently large-scale knife handles and palettes that I take to be part of a single chain of replications compare closely in outline shape and technique of manufacture with smaller, more routine examples of these artifacts commonly found in predynastic or early dynastic graves and datable in such contexts (see Baumgartel 1955, 1960). Early in this century, after his excavations of tombs with complements of different grave goods, W. M. Flinders Petrie worked out a fairly convincing morphological history for these routine specimens (see Petrie 1920, 1921, 1953). With subsequent corrections in Petrie's typologies and relative chronologies (Kantor 1944, 1965; Kaiser 1956, 1957), we now possess a general framework for dating the large decorated knife handles and palettes, most of which do not derive from dated graves. On the basis of all such typological analysis, the Oxford, Hunter's, Battlefield, and Narmer Palettes appear to have been manufactured in just this relative sequence—a sequence that is broadly accepted by a variety of scholars working with different evidence and interested in different aspects of the objects (for example, Bénédite 1916; Ranke 1925; Fischer 1958; Needler 1984: 329; Davis, 1989: 136–41; and probably Williams and Logan 1987).

In an absolute chronology (see Chronological Table, p. xvii) the works appear to span the period of the "late predynastic" or Nagada IIc/d—Nagada III (the knife handles and Oxford and Hunter's Palettes) through the early First Dynasty (the Battlefield and Narmer Palettes). In real terms, then, they cover at least eight to ten generations, from about 3300 B.C . (Nagada IIc/d) to the end of the fourth millennium (First Dynasty begins about 3000 B.C .). All of them derive from the period when the consolidated dynastic state and the he-

reditary monarchy emerged in ancient Egypt (see Hoffman 1979; Trigger 1983; and Kemp 1983 for general historical accounts of the period). The most critical state structures do not exist at the beginning of this development or they have not, at least, been fully interrelated one with the next: the period witnesses the emergence, increasing consolidation, and mutual coordination of a hereditary ruling elite headed by a powerful sovereign backed by force; a national bureaucracy of finance and administration and a transregional and perhaps even "imperial" organization of long-distance trade and commercial and military expeditioning; what will become a canonical script, art, and liturgy; and a self-proclaimed consciousness of the wholeness of the state legitimated by an ideology of cosmic order and divine kingship. By the end of this development, however, at the end of the fourth millennium, one of the most important elements of the state, an ideology of rule, will have been constituted within the image-making tradition. And in succeeding generations, in the first two centuries of the third millennium B.C ., the state is consolidated as a set of self-maintaining and interlocked institutions and ideologies (for the structure of the Old Kingdom state, see especially Weber 1978: 231–35, 1044–47; Janssen 1978; and Kemp 1983 and 1989, with Davis 1990c).

My interpretation of images decorating the objects shows this or a similar relative sequence and chronological attribution to be the most likely one. Despite a justifiable concern for exact chronology in the literature, however, little of deep interest depends on the specifics of the chronological sequence I accept. My analysis could be slightly rewritten to interpret a group of variously older, contemporary, or more recent depictions drawing selectively, or "disjunctively," on a common tradition of representation predating the complete emergence of the canonical tradition. Thus, for example, the Hunter's and Battlefield Palettes need not be regarded as respectively earlier and later; the archaeological evidence supports the possibility that they could be contemporary. Similarly, the Battlefield and Narmer Palettes need not be regarded as respectively earlier and later; they could also be contemporary, or even—considering the fluid, emergent nature of state institutions and ideology in the period—respectively later and earlier. The chronological or what George Kubler (1962) terms the "serial" position of an image is independent of its textual position—for example, as a

metaphor, allegory, or narrative—in relation to other existing texts and to what I call the general conditions of intelligibility of the possible varieties and species of textuality as such (Chapter 7). Without absolute dates to assign each object on independent archaeological grounds, we cannot always translate the analysis of textual positions into a specification of real chronological or historical relations.

Despite these subtleties, my analysis depends on showing that image makers knew and took account of one another's work as available or possible varieties and species of image making. These textual relations may go in various, sometimes unexpected directions—the sculptor of the Narmer Palette took account of the metaphorics of the Battlefield Palette, the Battlefield sculptor of the Hunter's Palette, and so on—but they are nonetheless particular, specific, and finite relations. For instance, the sculptor of the Brooklyn and Carnarvon knife handles evidently did not take account of the images produced by the Battlefield and Narmer sculptors. These two works are thus textually and almost certainly also chronologically earlier in the chain of replications.

If we discover that an image maker made use of a motif metaphorically—a possibility that is at the heart of my interpretation of the chain of replications of late prehistoric Egyptian image making—then we assume his awareness of other, alternative uses of the motif, metaphorical or nonmetaphorical. It is implicit in the very notion of metaphor that a standard or at least an accepted use of a linguistic or visual expression precedes or coexists with the secondary or "poetic" metaphorical usage (Black 1962; Goodman 1979; Podro 1991, with Davis 1991). Strictly speaking, however, we should not infer, without further evidence, that the maker of the metaphor depended on chronologically prior expressions. Instead, the totality or some substantial part of a system of expression could have been available to him at a given time, and he chose to use it in a "poetic" way while simultaneously other image makers used it in standard ways. This study concerns such textual relations among the replications of an expression—for example, a motif or style of rendition—and in turn between them and the general conditions of intelligibility that define a chain of replications as a series of possibilities in the first place. But, again, we cannot always qualify in chronological or historical terms the textual relations we might iden-

tify; there could be several plausible historical scenarios accounting for them and little or no independent archaeological means of confirming one or another. Whether it is even desirable to do so is a question I leave open for the moment.

Despite the paucity of independent evidence, it is obviously important to consider, where possible, the social and cultural world in which late prehistoric image making had a place. Unfortunately, although we know a good deal about some aspects of prehistoric society in the Nile valley, our sources fail us when we investigate the functions or meanings of images in particular. Beyond the fact that the objects we are observing date to the period of state formation in the late prehistoric Nile valley, we cannot say precisely what they may have assimilated from or contributed to this political and cultural process—broadly speaking, the replacement of relatively autonomous ranked social structures based on mostly regional economies and political interchange ("chiefdoms") by the transregional economy and politics of the state, certainly as much a structural as a chronological development.[3] It does appear that the human beings depicted on earlier objects in the group (about 3300 B.C .), like the Ostrich Palette, exhibit a relationship to one another and to the natural world different from those on later objects (about 3000 B.C .), like the Battlefield Palette. Moreover, the later objects conform more closely than the earlier to what would emerge by the end of the sequence and in succeeding generations as the principal standards of canonical representation. The crystallization of the Egyptian state is documented by numerous strands of evidence, from the patterning of settlements and cemeteries (for example, see Kemp 1973, 1982; Kaiser and Dreyer 1982; Davis 1983a; and Bard 1987, 1989) to the appearance of trans-regional and even international technological and perhaps conceptual connections (for example, see Frankfort 1951; Kantor 1965; and Davis 1981a). It is hardly surprising, then, that our objects reflect the real reorganization of the social relations and cultural activities of the neolithic economy according to the new rules of the emerging state.

The historical weight of this statement, however—that images probably reflect real social life and change—is actually rather vague in its implications. Insofar as they are representations, the images must also depict, symbolically and metaphorically, these or other social and historical realities—that is, any

and all states of affairs that can be designated by images within the general conditions of intelligibility of representation. Moreover, the activity of depiction is fully part of, perhaps an active and creative part of, social reality and development: making reference to reality is one of the principal components of reality. But in this regard, when we come to investigate the image makers' knowledge about, attitudes toward, and desires for what they chose to represent, we cannot place the objects specifically beyond recognizing them as instances of the conceptual labor of their time. The images actually constitute our primary evidence for their makers' knowledge, attitudes, and desires and for the nature of their engagement with social reality and development.

Notwithstanding the attempts of some Egyptologists, it would be naïve to take the depictions as straightforward pictorial documents of or for the events and processes of state formation. If we link the representation with the historical reality of what is supposedly documented by the image, we risk mistaking ideology and rhetoric for historical process itself. Whatever was really occurring in the villages, emergent regional polities, and nascent transregional institutions of late prehistoric Egypt, the images necessarily and by definition re-present this reality. They tell a story, perhaps the story of a history—and this, in turn, may be a history that never occurred. Given that information enabling us to back up these observations with a specific historical scenario is almost totally lacking, it makes as much sense to investigate the images as one of the empirical explanations for the emergence of the state in ancient Egypt as to suppose that we could somehow cite that history as an independent empirical explanation for the making of the images.

If in fact the evidence of chronology is any guide, the images may have played a directly formative role in transforming the political-cultural system. By stating symbolic propositions and narrating past and ongoing events, they framed general conditions about the intelligibility of the world and its history on which social decisions, actions, and institutions could be based. Functioning as relays of knowledge, ambition, and desire, they were not, then, just the results but also the instruments of the reconfiguration of the social order. For example, on archaeological and typological grounds the Brooklyn and Carnar-von knife handles, the Davis comb, and the Ostrich, Oxford, and Hunter's

Palettes should all be dated to the Nagada IIc/d or Nagada IIIa period, well before the climactic phase of state formation in the Nagada IIIb period and early First Dynasty. As images they relate a narrative of a human being's mastery of the natural and social worlds quite in keeping with the ideology of rule that characterized the complex dynastic state. But this is not to say that their narrative derives from or depends on the dynastic state. Rather, the images make sense in the context of an agriculturalist society practicing some real or ritual hunting. Thus, it would seem, the ideology of rule characteristic of the dynastic state was overlaid retrospectively by an earlier iconography of hunting for the ways it provided of referring to realities the artist hoped to retain or reconstitute (see also Davis 1989: 232–34).

We do not know whether the masterful human being depicted in the late prehistoric images had a real referent in late prehistoric society. Perhaps this personage was, in the real world, a successful hunter, a family leader, a powerful matriarch, a village headman, a "chieftain" of an internally stratified local polity, a regional warlord, or a conquering invader; but it is also conceivable—the possibilities are not mutually exclusive—that the image represented a partly or wholly imaginary being or state of affairs in a narrative symbol. The images are certainly complex and subtle enough to admit the possibility that this masterful human being was, among other things, an allegory for the artist himself or herself and probably also for his or her patron or the owner of the object. I use the designation ruler partly because other possible terms for a complex identity—mother, father, leader, chieftain, warlord, pharaoh, god, artist, patron—may be too literal, and certainly cannot be confirmed as historical, and partly because some or all of these real identities may be subsumed in the image as a whole. It is admittedly a leap of inference to assign this ruler to the male gender, as I generally do in this study purely for ease and consistency of exposition. Although the later monarchs of Egypt were usually male, we know little about the gender distributions of various forms of rulership in prehistoric society.

Precisely because we are dealing with representations we should credit the possibility that the ruler's "rule" is only within representation itself. The image making could apply as a complex metaphor not just to one literal situation of

someone ruling but also to several domains of life in which "rule" had an actual or conceptual reality—to all kinds of domestic, economic, military, and political contexts involving different people of different genders, which could be categorized and thus compared according to a flexible, general discourse for rule" as such. It seems to me that only this can explain the consistency and continuity of the late prehistoric tradition. Particular social situations of rule come and go, but all are mediated, as situations, by general conditions of intelligibility and a set of symbols, metaphors, and narratives of and for rule. The reality of political-cultural process at its most fundamental level includes the very representations we might otherwise seek to explicate in terms of political-cultural history. Thus any attempt to take the late prehistoric images as documenting this or that particular personage, situation, event, or context of "rule" would be inadequate to the literal reality of the history of representation.

By the same token, the identities I call the ruler's "enemies" within the representations could as well be interpreted as metaphorical. The antagonists presented in the several late prehistoric images I consider here include hunted animals and great carnivores as well as human beings. Not necessarily limited to the "real" enemies of the Egyptian state, these last could include anyone metaphorically "subject to rule," including the viewer of the image.

If we had reliable information about who made the images, when and where, and to what specific ends, we could then begin to disentangle some of these matters. We might, for example, be able to determine whether the images presented versions of well-known themes to a knowledgeable audience, and therefore could be understood to conform to a well-rooted, currently accepted tradition, or whether they projected the more unfamiliar representations of a controversial ideology. Some sense of these possibilities derives simply from evaluating the images in relation to earlier, contemporary, and even later images. For instance, the Battlefield and Narmer Palettes seem to revise substantially the pictorial text used on the earlier Oxford and Hunter's Palettes in a fashion closely tied to the images made on contemporary decorated knife handles and therefore apparently a well-established, widely distributed system of expression. Moreover, the Narmer Palette betrays some inconsistency in its own procedures and thus can be seen as attempting something genuinely novel.

Uses, Audiences, and the Representational Function

We know the owner of the Brooklyn knife handle by the other contents of his burial assemblage, Grave 32 at Abu Zeidan (Needler 1980, 1984). He was a relatively well-to-do townsman, with standard tastes in grave furnishings, who had the good fortune—possibly from family status, economic success, or political connections—to own one work of superb craftsmanship, luxurious, if somewhat conservative, in its design.[4] We know virtually nothing specific about the owners of the other objects. Like many examples of late prehistoric art from the Nile valley, the Carnarvon knife handle and the Ostrich, Hunter's, and Battlefield Palettes have no recorded provenance.

By contrast, the Oxford and Narmer Palettes come from the so-called Main Deposit at Hierakonpolis (Quibell and Green 1900–1901). But since it was a heterogeneous deposit of various objects, deposited at least several generations after the manufacture of the earliest works it contained, the context shows only that later owners or viewers somehow valued the earlier decorated objects and determined to preserve them. The motivation for their action—and whether they were interested in the images and could understand them—remains obscure.

Before a recent reanalysis and republication of the field books for the turn-of-the-century excavations at Hierakonpolis in which the objects were unearthed (Adams 1974, 1975), it was not fully clear to Egyptologists that the Main Deposit was in fact a heterogeneous collection. Some writers reasonably interpreted it as a dedication at an early temple of Horus or Hathor at Hiera-konpolis. The objects found within it would then have been offerings by royal patrons, such as the "Narmer" named on the Narmer Palette, to divinities (see Baumgartel 1955, 1960; Asselberghs 1961: 259). Although I do not assume a connection between the palettes from the Main Deposit and temple-cult or temple-furniture dedications at Hierakonpolis, my readings will not be incompatible with such a connection if it is confirmed by archaeological evidence yet to be discovered. Early First Dynasty shrines at Koptos (plausibly reconstructed by Williams [1988b]) included colossal statutes bearing motifs used elsewhere in late prehistoric image making but not necessarily with the same meaning;

these shrines are only suggestive evidence, then, that the decorated palettes were votive in function. The proposal that other palettes come from another early temple, in this case at Abydos (for example, Needler. 1984: 328), is unsupported by independent evidence.

Other accounts of the function of the objects (see Hoffman 1979) suggest that valuable and striking knife handles, combs, and palettes might have been given as gifts by senior members of a group to one another or to specially favored junior members. Likewise they might have been commissioned to commemorate important events in an individual's life. These hypotheses are somewhat independent of the question of their actual use after being given or commissioned. While the largest of the decorated palettes would probably have been impractical for continuous daily use as an ordinary cosmetic palette, we must admit, lacking evidence for a specific function, that we can hardly judge whether the palette was "practical" or not. Perhaps the larger palettes were set up for display in a residence or temple or were stored for use on special ritual occasions. But although some such ceremonial status for the objects is often asserted (see Petrie 1953), there is not a shred of independent archaeological evidence in the matter. In fact, prehistorians call an item "ceremonial" when they have no idea how it was used.

Even if correct, the hypothesis of ceremonial function is not helpful when we do not know the nature of the purported ceremony. Some Egyptologists propose that certain examples of late prehistoric or early dynastic Egyptian art document ceremonies known from contemporary textual sources or inferred from anachronistic parallels with later periods. For example, the Narmer Palette has been said to commemorate a celebration of victory over defeated "northern" enemies or a jubilee known as the Sed -festival (Schott 1950; Vandler 1952); and the Narmer mace head, an object apparently contemporary with and closely related to the palette, has been interpreted (Millet 1990) as documenting a festival of the "Appearance of the King of Lower Egypt" mentioned on the Palermo Stone (bearing part of a Fifth Dynasty text describing earlier "history") as having occurred sometime in the First Dynasty. There are several similar proposals in the literature. But even if the images do depict or document particular ceremonies, actually staged in the early dynastic period or merely imagined as ideal stagings by late prehistoric and early dynastic image makers, it is

not thereby shown that the objects or images were also used in and made for these ceremonies. Certainly nothing is said about the way the images, as depictions or documents, represent the ceremonies.

In implicit contradiction with the "ceremonial" hypothesis, the decorated objects are sometimes supposed to have had a magical function. For instance, they could have promoted success in the hunt or in battle or secured the favor of a totem or divinity; they could have been rendered magically efficacious in these or similar functions by their depictions, by a ritual use of the implement, or by both together in the context of a larger performance. The diversity and vagueness of all such accounts (compare Capart 1905; Baumgartel 1955, 1960; and Asselberghs 1961) confuse the issue. They seem to have been influenced as much by outmoded views of prehistoric or "primitive" art in general as by any reliable documentation. (Some Egyptologists have evidently endowed late prehistoric images with some of the "magical" properties of later dynastic funerary statues or liturgical implements, but we cannot assume functions and meanings closely associated with the developed theology and canonical iconography of the hierocratic state to have been present in the same way in the late prehistoric context.) Decorated objects found in tombs, like the Brooklyn knife handle, may be presumed to have served a general "magical" purpose for the life of the deceased beyond the grave. But despite numerous assertions in the literature, there is no archaeological evidence that the great carved palettes or the images carved on them had a magical function.

My reading suggests that construing the works as ceremonial or magical, possibly correct as far as it goes, is at best only a partial interpretation. As we will see, the images afford their viewers a particular representation of the natural and social worlds. They were probably intended less to alter those realities through ceremonial or magical means than to change people's minds through direct representation. We do not need the hypothesis of "magical" function, or any other functional hypothesis, to examine the discursive structure of the representations. In fact, some recent writers have assumed the highly rhetorical nature of late prehistoric image making, describing some of the images as "symbols of power generated as political propaganda" (Hoffman 1979: 299; see also the remarks of Finkenstaedt 1984; Hassan 1988; and Kemp 1989). To be sure, the pictorial mechanics of late prehistoric image making could support this

interpretation. The functional specification itself, however, must still be secured on archaeological grounds—for example, if we could determine that the decorated objects were used in the public display of elite authority—independent of an interpretation of' the representational character of the images as such.

Some aspects of the material could be said to speak against this particular "functional" hypothesis. Propaganda is often addressed by an elite circle to an outside, popular or mass audience that is otherwise not necessarily disposed to accept an interest group's view of the world. But we do not find the palettes in wide circulation, mass production, or public display, in contexts of nonelite or popular consumption, as we might expect if they functioned literally as propa-ganda. Perhaps the archaeological evidence is simply inadequate, as it is for the ceremonial" and "magical" hypotheses; or perhaps the objects had other functions altogether. Whether or not the objects were literally "political propaganda" may be independent of ways in which people might have attached sense to them in light of the pictorial mechanics and metaphorics I am suggesting. My interpretation is not incompatible with the notion that the representations sometimes functioned as propaganda or perhaps as other species of social communication and legitimation, but I regard all such possibilities as matters that might be investigated for historical purposes following a detailed examination of the chain of replications of late prehistoric image making.

Although the literal function of the objects remains obscure, we can make elementary inferences about their makers and about the audience they expected to address. Here again historical confirmations are few and far between. At least two people must have examined the objects and images: the maker and the owner, who probably stood in relation to one another as producer to consumer, retainer to master, or artist to patron. Early dynastic painters, sculptors, and woodworkers sometimes served as specialists in a ruler's immediate entourage, apparently resident at his principal court, for their graves have been found in the architectural complex of early dynastic kings' burials along with those of high officials (see Petrie 1927; Emery 1954: 29, 31, 143–44, 153–54), but many artisans may not have lived this way. While we cannot say definitively whether the objects considered in this study are examples of elite consumption, commission, or patronage, there are reasons to regard them as such: stylistic

similarities exist between them and objects known to have been made at the centers of residence or interment of the elite, like Nagada and Hierakonpolis (Petrie and Quibell 1896; Quibell and Green 1900–1901), or at centers of early cults, like Gebelein and Koptos (Davis 1981b; Adams 1984; Williams 1988b).

It would not greatly matter, however, if a lucky archaeological association showed that the palettes were made in a village for a local head of household, lineage leader, or "shaman," as might have been the case—we have no independent evidence—for objects like the Ostrich and Oxford Palettes. Perhaps they were owned and used simply by the people who made them, for the phenomenon of craftsmen employed full time for an elite patron—one of the achievements of canonical representation (see also Davis 1989: 217–21)—may not have been present at all levels of late prehistoric Egyptian society. It is entirely possible that the sculptors were not in close connection with one another, as they would be if they worked in the same workshop or for the same patron. Local residence of the artisans and regional diversity among them could be one explanation for the distinct stylistic differences among certain groups of carved palettes (see, for example, Ranke 1925; Fischer 1958; and Davis 1989: 155–58).

Whether the objects were displayed to or viewed by a wider public circle beyond maker and immediate consumer, master, or patron cannot be readily determined. Despite their sometimes unwieldly bulkiness, even the largest palettes were made—common sense tells us—to be handled and inspected at close quarters, however few the viewers or how restricted their access. The images seem to be organized as narratives to be "read" in a specific way, if not by actually handling the object at least by moving around it to view its several, separate passages of depiction and the composition of the image as an emerging but open-ended totality. The actual situation of this activity of viewing, however, is unknown. Did it transpire in a ritual setting? Was the object set up for display or could a person actually take it in his or her hands? The various objects in the group, different in size one from the next, may have been handled or viewed in different ways depending on factors we cannot now reconstruct. Finally, the images must assume an audience and a particular mode of viewing at a notional level, but we cannot say whether the assumptions were literally to

be fulfilled. Like the makers of stained-glass windows high in the walls of a medieval cathedral, the late prehistoric Egyptian image makers may have produced objects and images simply according to their proper rules, expecting no one to make out their intricate details.

All these questions about functions and uses are somewhat beside the point I make in this study, not because they are irrelevant but because of what I take to be a prior and overarching consideration. Irrespective of the possible documentary, votive, commemorative, ritual, ceremonial, magical, exchange, propagandistic, or other functions of the decorated objects, they work as pictorial narratives. While their representational function may appear so obvious as to be uninteresting, it is both broader and more penetrating than the other specifications I have reviewed—for all of them must be seen as aspects of a particular function or functions of what is already functioning as representation. In fact, paradoxically, most of the specifications I mention are too general. Other activities or artifacts apart from images, as well as other sorts of images, could have served successfully in ritual, magical, ceremonial, or propagandistic ways; and therefore we still have to develop a specific analysis of these objects as fulfilling such functions by way of the images depicted on them. A scholar outside the disciplines of prehistory and Egyptology—for example, in literary criticism or art history—might be surprised by attempts to identify possible functions in the absence of a rigorous formal identification and textual analysis of the images themselves. How could we determine the function, or social use, of the image even before defining what we are looking at?

The Question of "Sources"

Historical information about the production and use of the objects is so hard to come by that we must simply make the best of an unfortunate situation by exploring the material we do have—namely, the images themselves. Because the problems of evidence are so acute, however, two other possible sources of information have been mined heavily by a number of writers—first, other prehistoric representation, and second, its canonical descendants and analogs.

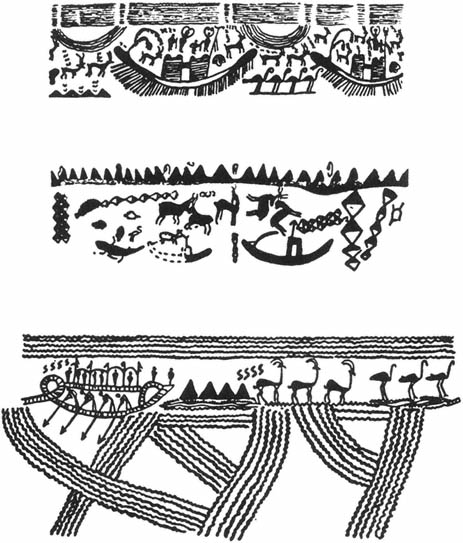

Several writers have investigated the possible stylistic and iconographic sources of and parallels for decorated ivory knife handles and combs and schist palettes in earlier and contemporary media like rock art, pottery design, wall painting, and textile decoration (see Vandier 1952; Williams and Logan 1987; Williams 1988a; further references and comments are found in Davis 1989: 116–34). The prehistoric traditions of representation in the Nile valley emerged as early as 8000 B.C . in "abstract" engravings produced on rock faces near the present-day towns of Abka and Wadi Halfa at the second cataract of the Nile (Myers 1958, 1960; Hellström 1970; Davis 1989: fig. 6.1). Although production in other media is less well preserved and consequently less well known, there were in fact rich and changing traditions, particularly in rock art and pottery decoration. It is not surprising therefore to discover in them apparent antecedents or analogs for many elements of the late prehistoric images on knife handles and palettes, the latter forming just part of a larger, longer history of production.

It may be that this tradition derived some stylistic mannerisms and iconographic motifs from older or contemporary Near Eastern sources, a possibility urged long ago by Henri Frankfort (1925: I, 93–142; 1941; 1951: 121–37). More recent studies would date this relationship to the relatively well-defined period of the Nagada IIc/d (Boehmer 1974a), suggesting that at least one medium of the diffusion of motifs may have been small, portable roll seals, although the seals actually found to date in Egyptian predynastic contexts do not themselves document transmission of the particular features Frankfort cited (Boehmer 1974b; see also Kantor 1942, 1952, 1965; Trigger 1983: 36–38; Mode 1984; Teissier 1987). Foreign influence is in question precisely because we do not yet have a clear idea of the general conditions of intelligibility of late prehistoric image making and because it is still judged in light of later canonical standards. Thus it is difficult to decide whether a mannerism or motif, by virtue of appearing untypical or "un-Egyptian," is therefore to be ascribed to external influences; and some writers are rightly skeptical of the entire account of diffusion (Kelley 1974). Merely for the purposes of argument, we can grant that motifs like the human being mastering opposed animals, the serpent-necked felines (or "serpopards"), and the winged griffin—all appearing on late

prehistoric Egyptian ivory knife handles or palettes—are virtually certain examples of motifs with an ultimate origin in Mesopotamia, perhaps mediated by small Mesopotamian seals on which the motifs can be identified substantially earlier than the Egyptian uses (Porada 1990).

It is not clear, however, exactly how any of this fine-tuned research pertains to art-historical phenomena. A stylistic or iconographic source can always be cited for an element of a passage of depiction, if not of the image as such; all cultural practices necessarily have cultural heredity, just as biological individuals have biological heredity. But to identify a source, presuming it is a real one, is not thereby to understand the role of the element in any one of its immediate semiological contexts. An artist might appropriate a motif from another artist's work, or even from another culture, and put it to quite independent use, altering its established meaning by inserting it into a new compositional setting. For example, some commentators have suggested that the intertwined serpopards on the Narmer Palette symbolize the unification of Lower and Upper Egypt (Gilbert 1949; see also Finkenstaedt 1984), a meaning that presumably had nothing to do with the "original" Mesopotamian prototype of serpent-necked beasts. I myself contend that the intertwined serpopards on the Narmer Palette play a highly specific role in the narrative mechanics of the image—a role distinct from their appearance, for instance, on the Oxford Palette. Source hunting alone will not expose these relations. Indeed, source hunting based on a ramified description and comparison of many disparate images taken out of different contexts, unqualified by attention to the coherence of each image, distracts from the questions of narrative or symbolic meaning. The possibility of a Mesopotamian or other Near Eastern origin for some late prehistoric Egyptian motifs tells us nothing about the symbolic function—for example, the metaphorical or narrative status—of these motifs as they were replicated by late prehistoric Egyptian image makers. It would be interesting to discover that the late prehistoric image maker expected viewers to see or to sense the Mesopotamian origin as an aspect of the motif chosen and thus a reference or connotation of the image as a whole; but we could establish this textual relation only by scrutinizing the mechanics of the image—not simply by pointing to a Mesopotamian analog or even to a possible medium of diffusion of that analog.

There is a strong chance that in a detailed examination the apparent analogs for late prehistoric Egyptian images will turn out to be paralogs, mere unrelated similarities, or even pseudologs, false similarities. The institutions of canonical image making that enforced conformity to an established set of rules had not yet fully emerged in the late prehistoric period. We cannot assume, therefore, that each use of a motif in the precanonical context meant applying the same rule or rules, as it would in the fully canonical context. There is no guarantee that a source is really a source or a parallel really a parallel; a sign made according to the criteria of one symbol system differs from that made according to other criteria, even if the morphology of the two signs is indistinguishable (see Goodman 1972; Danto 1986).

At the time he laid the theoretical foundations for iconographic histories, Erwin Panofsky (1939, 1960) was aiming for what he called an "iconology"—namely, an explication of styles and motifs within the historical horizons of their unique cultural uses (see also Kubler 1985). Thus, although the Good Shepherd figure of early Christian iconography might derive iconographically from earlier Classical depictions of the beardless, athletic young hero, we would not think to explicate the Shepherd merely as a version of a Classical hero or Apollo type. Rather, in a process Panofsky (1960) termed "iconographic disjunction," the Shepherd figure capitalizes on its contemporary viewers' knowledge of the Classical type in order to make both traditional and novel, metaphorical statements about the identity of Christ, a reference to an object—or, let us say, a new sense for the available reference to a hero—that could not have been known to Classical audiences. At some point the relevance of the Classical reference simply fades away and ceases to matter in identifying and understanding what the latest makers and viewers experienced in the image.

It is virtually guaranteed, I think, that a similar situation obtained in prehistoric, late prehistoric, and early dynastic Egyptian art. For example, an artist like the sculptor of the Battlefield Palette knew the production of a relatively immediate predecessor like the sculptor of the Hunter's Palette. But their relationship was an intricate and subtle one: the Battlefield sculptor took a motif from the Hunter's Palette and by inserting it into a novel narrative context charged it with an entirely different sense. Although almost all mannerisms and

motifs must have sources, their referential dimensions can be seen to have evolved considerably over the span of the many decades or even centuries of the late prehistoric period; only in this way can we make sense of the distinct qualities of several late prehistoric representations.

Such iconographic disjunction, I maintain, characterizes not only the relations among the individual decorated knife handles and palettes but also the relations among these objects and the other media in contemporary or earlier Egypt that are sometimes cited as the iconographic origin or "conceptual basis" (Williams and Logan 1987) for elements of the knife handles and palettes. Making such an assumption means that I spend much less time citing these relations than has been usual in Egyptology. (Some "iconographies" or iconographic histories of predynastic and early dynastic motifs are available [for example, Williams 1988a]; all, however, are subject to the reservations I have mentioned.) In contrast to vulgar iconography's usual source hunting and parallel quoting—many images are reviewed to identify the so-called development of a motif, plucked from its semiological contexts—each image, presuming we can identify it, is taken here as a semlotic whole. It must be interpreted in depth before any iconographic relations among images, from quotation and influence through metaphor and parody to genuine dissimilarity and disjunction, can reasonably be inferred. To follow these relations into other, earlier sources or across media would not only greatly lengthen my account; it would also deflect attention from the properties of pictorial disjunction as the very structure of an image-making tradition. As a practical matter I do not consider all known decorated knife handles or carved palettes of the Egyptian late prehistoric period. Although motifs in all of them can be described and compared, some are simply too fragmentary to support a close and comprehensive interpretation of the organization of the image.

When properly combined with other inquiries, the comparative approach in motif typology—hunting for "sources" and quoting "parallels"—has a limited role to play in historical interpretation. For example, in an investigation of pictorial meaning that recognizes formally similar motifs as having many disjunctive symbolic connotations in a group of images, motif typology might show that one image must be later (or earlier) than another. In some cases motif

typology can be transformed into chronological analysis or an interpretation of historical interrelationships among image makers and viewers. But it cannot establish such conclusions on its own. The objects considered here have a relative chronology based not so much on the morphology of particular motifs as on the morphology of the outline shapes and related attributes of the artifacts themselves (Petrie 1920, 1921; Kaiser 1956, 1957). At any rate, since the motif-typological approach has generally dominated many branches of prehistoric art studies (for instance, see Davis 1990b: 272–74), another approach is required to give proper attention to the coherence of particular images, whether or not we wish to compile larger comparative typologies of stylistic mannerisms, motifs, or other features of passages of depiction.

Canonical Standards and Late Prehistoric Images

Similar considerations apply when we measure a second type of possible evidence for explicating late prehistoric images. Just as they must derive from an earlier history of making images, so too do they form the historical context for subsequent production—namely, for canonical Egyptian representation. The late prehistoric image maker could not have been fully aware at the time of the "serial position" he occupies in a continuous art history (Kubler 1962). He could hardly have planned for all the selections canonical image makers would make from particular aspects of his production—for example, they adapted what I call the several "core motifs" of canonical iconography from the repertory of prehistoric art (Davis 1989: 59–63)—or for all the new references they would assign to the images he left them, for example, in the very act of depositing the Oxford Palette, a late prehistoric object of Nagada IIc/d date, in the Main Deposit at Hierakonpolis, an early dynastic or even later assemblage. Why, then, should the canonical image maker's selections and references be considered relevant in interpreting the late prehistoric image maker's work?

Despite the obvious anachronism many writers on late predynastic and early dynastic art in Egypt have taken what we know of canonical art, hieroglyphic script, and Egyptian ritual, mythology, and cult—a literate tradition based on stable rules associated with the specific social formation and ideology of the

national, authoritarian, theocratic state—and applied it back to images produced in a less complex, almost wholly preliterate society. However ingrained in the Egyptological imagination, the procedure is completely unsound methodologically.[5] As far as possible I avoid applying decidedly canonical regularities to a precanonical or noncanonical context.

At one point this general rule—in that it is a general rule—will need to be relaxed slightly to afford us a useful line of interpretation in a special, limited case. Sited midway between the Oxford Palette at one end of our chronological continuum (about 3300 B.C .) and the register compositions of Old Kingdom public and mortuary art at the other (from about 2700 B.C . and on), the Narmer Palette (about 3000 B.C .) can be considered at one and the same time as the last exemplar of late prehistoric, noncanonical representation in Egypt and as the first canonical work. We are thus inclined to see it in retrospect as a "mixed," transitional, or transformational production, even though the original maker of the palette and his audience could not have seen the image in this way. But rather than merely worrying about characterizing the Narmer Palette in developmental terms, we should also question our rationale for framing it chronologically or historically as we do. For this and other reasons, it is a matter for delicate judgment in interpreting it to apply canonical rules or noncanonical rules or no rules at all. Reasonable interpreters can reasonably disagree about how the balance should be struck. But this is so for every representation; every representation is a revision within a chain of replications.

By virtue of its application of hieroglyphs, use of a proportional scheme, and tendency to magnify the scale of important figures and scenes, the Narmer Palette is often placed at the beginning of canonical Egyptian art (for instance, Aldred 1980). Partly in order to balance this point of view with its inherent risk of strong anachronism, I suggest that in fact the Narmer Palette is distinctly "prehistoric" in its underlying pictorial mechanics. It is most properly legible according to a narrative symbolic system that seems to have no direct canonical descendants, for canonical artists and patrons in the First through the Third Dynasties elected to replicate the symbolic rather than the narrative dimension of that inherited system.

Pursued too single-mindedly the question becomes utterly empty, a case of the sterile typology chopping that so debilitates prehistoric archaeology and of the style fetishism that so debilitates art history. General categories—like prehistoric and historic or canonical and noncanonical—break down when the particular semiological dynamics of a specific image are investigated in any depth. It hardly matters whether the Narmer Palette is regarded as canonical or non-canonical or some mixture of both, if we can make sense of the way it has been put together as an image. Unsettled and uncertain, disjunctive and decomposing, the Narmer Palette is an image that literally has two sides.

Most writing on late prehistory in the Nile valley has been dominated by anachronistic decipherments and by a determination to identify what is "Egyptian"—that is, interesting from the point of view of a discipline devoted to the study of dynastic Egypt—in the cultural history of the Nile valley and northeastern Africa (see also O'Connor 1990; Davis 1990b: 274–79). As with iconographic "sources," analogies for late prehistoric practice in later cultural life may be highly suggestive if there is independent evidence that the earlier and the later images did in fact represent their objects, as images, in the same or closely similar ways. It turns out, however, that little of real interest hinges on information gleaned from canonical sources. Here or there a motif might be more precisely identified, a gesture understood, or a glyph deciphered by calling on our knowledge of canonical representation. But by and large the late prehistoric image maker's practices were intelligible to him and to his audience in their own terms, at best only vaguely including the future possibility of a canonical, academic art for a dynastic, patrimonial state.

If depending on earlier and later analogies for late prehistoric practice is a questionable method, the use of general ethnographic or historical analogy outside the northeastern African and Egyptian setting is likely to be even more so. What we know of prehistoric arts, such as Upper Paleolithic cave painting or neolithic pottery decoration, and of historical styles like Roman narrative relief or medieval architectural sculpture might suggest means of understanding late prehistoric images in Egypt. All such suggestions, however, have the same status as the promptings of our intuition or visual scrutiny of the objects; they

are no more and no less reliable. In fact, an ethnographic or historical analogy can be misleading inasmuch as it may distract from the fundamentally disjunctive structure of all chains of replication and from the necessarily specific semiological context in which any given replication has been used. While I have learned a good deal, throughout this study, from what has been written about arts other than the ancient Egyptian, there is no need to introduce my experience in detailed comparisons. An interpretation cannot be strengthened by the existence of the analogies, from whatever visual, ethnographic, or historical context, used in working it out.[6]

The Temporality of "Meaning"

So far I have been making uncontroversial points. Historical interpretation of late prehistoric image making must avoid, as scrupulously as possible, teleological and anachronistic formulations and misleading visual or historical analogies. It is necessary to insist on these matters only because—in their source hunting and wild analogizing—too many analysts in prehistoric archaeology and Egyptology violate the rules of historical method. Most of the substantive problems for historical interpretation lie well within the purview defined by these somewhat banal methodological injunctions.

For example, although we may wish to avoid teleology in historical analysis, we still need to recognize the goal-driven, the forward-directed quality of an image maker's intentions. An image maker will anticipate a certain response to his work, plan for a certain use, or expect a certain interpretation to be applied to it. He works with extensive present beliefs about future audiences, including a sense of the ways that audience might repeat, revise, or refute the work and therefore, working from the future back into the present, of ways the work might be rendered more legible, more convincing, or more immune to alteration.

Similarly, although we prefer to avoid anachronism in historical analysis created by reading back from later meanings into contexts in which they had not yet been constituted, we must nonetheless acknowledge the memory-filled, backward-looking quality of a maker's intentions. An image maker may fully

incorporate even as he revises an existing proposition or mode of expression remembered or inherited from the past. Taking up materials from the past of image making as an element of his present intentions, the image maker may represent the past in his work as anything from a mere material precondition, the bare necessity of existing materials, to a virtually absolute cognitive determination, a full intentional embrace of the past.