Preferred Citation: Metcalf, Alida C. Family and Frontier in Colonial Brazil: Santana de Paraíba, 1580-1822. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3s2005k7/

| Family and Frontier in Colonial BrazilSantana de Parnaíba, 1580-1822Alida C. MetcalfUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1992 The Regents of the University of California |

To My Parents

Helen Waterman Metcalf

and

John Trumbull Metcalf, Jr.

Preferred Citation: Metcalf, Alida C. Family and Frontier in Colonial Brazil: Santana de Paraíba, 1580-1822. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3s2005k7/

To My Parents

Helen Waterman Metcalf

and

John Trumbull Metcalf, Jr.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in the citations:

Archives | |

ACDJ | Arquivo da Cúria Diocesana de Jundiaí |

ACMSP | Arquivo da Cúria Metropolitana de São Paulo |

AESP | Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo |

AHU | Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, Lisbon |

AN | Arquivo Nacional, Rio de Janeiro |

ATT | Arquivo da Torre do Tombo, Lisbon |

Manuscript Collections of Documents | |

IPO | Inventários do Primeiro Ofício, AESP |

IT | Inventários e Testamentos, AESP |

LP | Livros de Parnaíba, AESPè |

MP | Mapas de Populaão, AESP |

LPS | Livros Paroquiais de Santana de Parnaíba, ACDJ |

Published Collections of Documents | |

IT | Inventários e testamentos , Departamento do Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo |

DI | Documentos interessantes , Departamento do Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo |

Boletim , Departamento do Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo | |

Sesmarias , Departamento do Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo | |

Acknowledgments

When I first visited Brazil in 1967, we crossed the Amazon by motorboat from the Colombian town of Leticia and spent the day in the tiny village of Benjamin Constant. I could not have imagined then that one day I would write about the settlement of the vast Brazilian frontier. As my family and I walked down the muddy street among the houses built on stilts, and as we visited rubber tappers, we found ourselves in a world dramatically different from the one we knew. I realize now that the Indians, rubber tappers, hunters, and fishermen whom we met on that unforgettable trip were living as their forebears had lived generations before. Entering that world was stepping back into history, into the world of the individuals whose lives I reconstruct in this book. Although this book is set in a very different town, Santana de Parnaíba, located not in the Amazon but in the state of São Paulo, the families of Santana de Parnaíba sent most of their descendants into the frontier, perhaps some even to the remote village I visited in 1967.

Re-creating the lives of the people of Santana de Parnaíba in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries has been an intensely challenging task that has occupied me for the last fifteen years. I am deeply grateful to institutions, colleagues, friends, and family who made it possible for me to write this history.

First, I wish to thank the institutions that funded my research. A Fulbright-Hays fellowship from the U.S. Department of Education and a grant from the Social Science Research Council funded the bulk of the archival research in Brazil and Portugal in 1979 and 1980. The Mellon Foundation, the Institute of Latin American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, the University of Texas at San Antonio, and Trinity University supported research at the Nettle Lee Benson Latin American Collection of the University of Texas at Austin during the summers of 1985 and 1988. The Joullian fund, granted by that family to the Department of History of Trinity University for faculty development, made it possible for me to visit Brazil in 1989 and to hire student assistants. I am grate-

ful to each of these institutions and to the Joullian family for their support of historical scholarship.

Many happy memories of times spent with friends and colleagues in Brazil and the United States are woven into the researching and writing of this book. Richard Graham deserves special recognition for helping this project grow from its earliest beginnings and for offering excellent critical advice at many stages along the way. Sandra Lauderdale Graham first introduced me to the Brazilian archives; her ability to make history come alive from the sources has been an inspiration. Laura Graham helped me to understand the forces affecting Indians in the modern frontier, which has influenced my portrayal of similar forces in the past.

Working in Brazil has been enormously interesting and enjoyable. I am deeply grateful to many Brazilian colleagues who graciously received me in their homes, shared their ideas, and helped me to understand colonial and modern Brazil. The work and friendship of Eni de Mesquita Samara, whom I first met in Austin in 1977, has been instrumental to the development of this study. Mafia Luiza Marcílio's studies of São Paulo made it possible for me to place Santana de Parnaíba into a larger context; I am also grateful to her for her excellent counsel as I formulated my research methodology. My understanding of the lives of Brazilian women has been greatly advanced by historian Mafia Beatriz Nizza da Silva, whom I also thank for her enthusiastic encouragement of my work. The unfailing good humor of Fernando Novais has made the study of colonial Brazil always a pleasure. Iraci del Nero da Costa has sent me numerous articles to keep me informed of work being done in Brazil. Robert Slenes introduced me to many Brazilian colleagues and to the intricacies of slave family life. Jacy Machado Barletta took my friend Cecilia Pinheiro and me on a memorable tour of Santana de Parnaíba in 1989.

In 1986, as a visiting Fulbright Lecturer, I taught at the Universidade Estadual Paulista in Assis. The generous hospitality of Anna Maria Martinez Correa and the friendship of my colleagues there, especially Manuel Lelo Bellotto, Elizabeth and David Rabello, Olga Mussi da Silva, and Glacyra Lazzari Leite, as well as that of my students, made me feel a part of this institution.

I conducted the majority of my research in the manuscript collections of the Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo, where Dona Glorinha and Dona Azoraidil of the manuscript section helped me

to locate sources and to master paleography. To them, and to the former director of the archive, Dr. José Sebastião Witter, who honored many requests, I am most grateful.

Research assistants helped me at many stages of the project. I could not have finished my research without the excellent assistance of Ines Conceião de Inacio and Wilma Gomes da Silva. In Austin, Pedro Santoni entered reams of data into the computer. At Trinity University, Elizabeth Thompson coded the 1820 census, while Deanna Perez compiled the bibliography.

I wish to acknowledge the support of the chair of my department at Trinity University, Terry Smart, who facilitated my requests for research assistance, travel, and library research so essential to the completion of this book. My colleagues John Martin and Colin Wells read the manuscript and offered valuable suggestions. At the Trinity University library, Carl Hanson answered numerous questions about Portuguese history and helped me to locate rare books. In the library's Instructional Media Services, Pat Ullman, Patricia Beneze, and David Garza drew the maps, produced the figures, and photographed the illustrations.

I also wish to thank the readers for the University of California Press who reviewed the manuscript; their excellent suggestions, incorporated into the final revision, greatly improved the book. I wish to thank my editors at the press, Edward Dimendberg, Shirley Warren, and Michelle Nordon for shepherding the book through production.

I have explored some of the ideas presented in chapters 2, 4, and 6 in articles published in The Hispanic American Historical Review, Estudos Econômicos, The Journal of Family History , and Mark D. Szuchman, The Middle Period in Latin America: Values and Attitudes in the 17th-19th Centuries .

In my own family, my uncle, William Van Antwerp Waterman, first interested me in family history and genealogies. My husband, sociologist Daniel Rigney, carefully read the manuscript and offered numerous suggestions that clarified my ideas and their presentation. Our young sons, Matthew and Benjamin, have given me a new appreciation for the meaning of family life. And finally, it is with great pleasure that I dedicate this book to my parents, Helen and John Metcalf, whose love has followed me everywhere.

A. C. M.

SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS

APRIL, 1991

A Note on Currency

The common currency of colonial Brazil was the real , plural reis , although many other coins, as well as gold dust, circulated. One thousand reis, or one mil reis, was written 1$000. To alleviate confusion in the text, I have replaced the $ with a comma; hence 1$000 becomes 1,000 reis. While it would be difficult to give meaningful modem equivalents, some comparative values might be helpful to the reader. In the eighteenth century, a strong slave in the peak of his or her working years was worth between 100,000 and 150,000 reis.

A Note on Orthography

The Portuguese language has undergone several reformulations to standardize orthography. This poses difficulties for social historians, for the accepted modem spelling of proper names differs from that found in colonial documents. In addition, the notaries who wrote and transcribed these documents often used their own spelling. To complicate things even further, individuals often had several family names, all of which might not be recorded in every document. I have adopted the standard modem usage for prominent historical figures and places—for example, Santana de Parnaíba—regardless of how they were spelled in the documents. I have not, however, modernized the spelling of the names of the people of Parnaíba. Instead, I spell their names as they appear in the documents. Where variations of the same name appear, I have adopted the most common one.

Introduction

Family, Frontier, and the Colonization of the Americas

This book tells the story of ordinary people who lived simple lives in four adjacent parishes that once formed a large rural town in southern Brazil. Although historians have rarely been interested in these people, the majority of whom were slaves and small farmers, they did have an enormous influence on the colonization of this region of Brazil, today the state of São Paulo. By the manner in which they lived, unpretentious and unselfconscious as it was, they established certain lifeways that directly shaped the character of the society in which they and their descendants lived.

The inheritance of cultural attitudes and economic resources from generation to generation among the people of this community, Santana de Parnaíba, from the time when the Portuguese first landed on the coast of Brazil in 1500 to the birth of the Brazilian nation in 1822, is the subject of this book. Santana de Parnaíba serves as an excellent microcosm for the analysis of how families survived in the world of colonial Brazil. Passed through family life to succeeding generations, their family strategies became a cultural inheritance that shaped the community and the development of the western frontier. Moreover, given the continued expansion of the agricultural frontier into the modern Amazon basin, the survival strategies of these people in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries explain why similar strategies continue to be used by their descendants in Brazil today.

I argue that the strategies of families, in relation to the frontier, are critical to understanding the colonization of this region of Brazil. Not only does this relationship help to explain the process of colonization but it also holds the key to understanding the origins of social stratification. Power and wealth in this region have come from the frontier, but not all have had equal access to it. Those families and social classes that controlled the development

and exploitation of the frontier came to dominate the region economically and politically.

In Santana de Parnaíba, colonization occurred in discrete stages. In the first stage, Santana de Parnaíba was itself a frontier—poised between the wilderness to the west and the city of São Paulo to the east. As colonists came from São Paulo to the region and began to settle there in the late sixteenth century, a society emerged which blended Indian and Portuguese ways. Although it was not an egalitarian society, it was a fluid one, and social mobility was possible for those of Portuguese descent who successfully acquired land and Indian slaves from the wilderness. After Santana de Parnaíba became an established town in the early seventeenth century, it served as a jumping off place for the frontier to the west. Throughout the seventeenth century, men from Parnaíba, but only occasionally women, set off into the frontier in search of their fortunes.

As the town grew and became a more complex community in the eighteenth century, it entered a second stage. Social classes began to emerge. A cash-crop commercial economy took root in the town, as did investments in commerce and mining. The influence of Indians waned. Slavery remained pervasive and unquestioned, but Africans replaced Indian slaves on the agricultural estates of the town. As in the first stage, those of the town who successfully exploited the frontier became or remained the wealthy and powerful in Santana de Parnaíba. The frontier continued to hold the key to social and economic success in the town.

In the third stage of this process, Santana de Parnaíba lost its ties to the wilderness and declined while towns farther west, many of which had been founded by men and women from Parnaíba, flourished. In this last stage, Parnaíba continued to remain a stratified community, with few rich slave-owning planters and an increasing number of small slaveless farmers. Eventually, the town faded into obscurity and became dependent on the growing city of São Paulo. This third stage began in the early years of the nineteenth century in the central parish of the town, somewhat later in the outlying rural parishes, and continued through the nineteenth century as the coffee frontier boomed farther west. Today, Santana de Parnaíba has entered a fourth stage as the region increasingly becomes part of greater São Paulo. The popula-

tion has grown as city workers have sought inexpensive housing. Wealthy families have built expensive vacation homes there, too. By the next century, Santana de Parnaíba may well be another suburb of the city of São Paulo.

In each of these stages of development, the relationship between families and the frontier played a major role in shaping the lives of their individual members and structuring the contours of community life. Attitudes about how to survive that families consciously and unconsciously adopted affected how they perceived the frontier, raised their sons and daughters, divided their property, and farmed their lands. Many of these attitudes were formed in the first stage of colonization when families adapted and experimented in order to survive. One such attitude was the belief that the wilderness held the riches that individuals and families needed to survive in the town. This attitude had developed during the earliest stage of colonization and continued to characterize life in the later stages because of the proximity of the frontier.

The history of the frontier in Brazil holds much in common with the history of the frontier in North America. Indeed, the most influential work on the role of the frontier in American history describes some of the same features of the Brazilian frontier. In 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner's remarkable paper, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History," argued that America was different from Europe because of the frontier, the meeting point between wilderness inhabited by Indians and an expanding European population.[1] The existence of the frontier, and its continued colonization by wave after wave of colonists, was what in Turner's eyes made America unique. While in their first settlements along the Atlantic coast colonists did re-create much of their European culture, as they moved west they had to adapt to the wilderness and be transformed by it in order eventually to master it. Turner writes, "Moving westward, the frontier became more and more American.... Thus the advance of the frontier has meant a steady growth of independence on American lines. And to study this advance ... is to study the really American part of our history."[2] For Turner, the "really American" part of American history was the growth of individualism and democracy on the frontier. These values created the basis for an American nationalism. Turner's thesis has been developed[3] and critiqued[4] by later histo-

rians, but his work remains provocative because of the questions he posed and the issues he raised.

Brazilian historians such as Sérgio Buarque de Holanda also perceived the frontier to have been a critical factor in Brazilian development.[5] Like North America, Brazil began with a handful of coastal settlements that faced the Atlantic while behind them extended a vast, and to them unknown, wilderness. Brazil has expanded west, devouring the lands of Indians and creating a new, distinctly Brazilian culture. Brazilian development has depended on the cheap lands and resources of the frontier. But there is a big difference. The frontier in Brazil has rarely bred democracy or individualism. While many historians of North America now question whether the frontier in the United States really fostered democracy or individualism,[6] the contrast with Brazil is nevertheless striking. In northeastern Brazil, huge cattle ranches effectively colonized the frontier and concentrated immense tracts of lands into the hands of a few. In the south, sugar and coffee planters sought virgin forests to fell and transform into large agricultural estates worked by slaves. Relatively few parts of the Brazilian frontier were colonized by the yeoman farmers so eulogized by Turner—the hardworking entrepreneurial families who carved their homesteads out of the wilderness by the sweat of their own brows. While small farmers did move into the frontier in Brazil, they rarely legally owned the lands they claimed. As a result, when large agribusinesses arrived, they pushed out the small farmer, who either moved west, became a sharecropper, or migrated to the city.

As I will illustrate, the frontier provided the resources that allowed a small elite to form and to become wealthy and powerful in a town such as Santana de Parnaíba. Because of the way this elite perceived the frontier and made it an integral part of their family lives, succeeding generations of elite families were launched into the frontier, where they too found the resources to make themselves wealthy and powerful in their respective local communities. Other social groups did not benefit equally from the resources of the frontier and did not successfully incorporate strategies for developing the frontier into their family lives. Small farmers subsisted off the frontier but did not use it to make themselves wealthy, while slaves did not have the opportunity to ac-

quire its resources. Thus, the way the frontier has been developed in Brazil is one of the roots of inequality in Brazilian society and continues to be to this day.

A second source of inequality in Brazilian society springs from family life. Historians of Latin America are increasingly aware that the family, particularly the elite family, has been one of the most powerful forces in colonial society. Though the region's economic and political institutions were planted in the colonies by Spain and Portugal, the families of the Creole (native-born) elites managed to infiltrate these institutions and to use them to their advantage. In the process, they deeply affected the character of colonial society itself.

After the discovery and conquest of Latin America, the colonies offered many opportunities to individual Spaniards and Portuguese who found the means to come to the New World. As these individuals settled and eventually formed families, they increasingly chafed at the many restrictions placed on them by Spain and Portugal. In particular, Spain regulated the colonies excessively, always with the intent of squeezing as much revenue from them as possible. These regulations continually hampered the aspirations of early conquerors and settlers. Such an environment meant that families that did succeed economically—through investments in agriculture or mining, for example—had to be exceedingly crafty to maintain their power and influence.

Historians of colonial Mexico and Peru have documented the exceptionally complex strategies that elite families pursued to preserve their status and influence. Studies by David Brading, Doris Ladd, and Richard Lindley (among others) for Mexico and Susan Ramírez, Fred Bronner, and Robert Keith for Peru illustrate how an elite formed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and how, through their families, they maintained their power and influence.[7] They did so by carefully marrying their daughters, by grooming their sons for careers in the church or government or as managers of agricultural estates, by maintaining an extended kin network, by establishing fictive kinship ties to other influential families, and by planning for the transmission of property through inheritance. These strategies made the landowning elite rich and powerful and made it difficult for other social groups to achieve

upward social mobility. Spain's colonial caste system, based on purity of blood (limpieza de sangre ), further strangled the aspirations of the poor mestizos, blacks, and Indians.

In Brazil, a colonial society less rigid than Spanish America, a similar process occurred. In the sugar-growing region of the northeast, a powerful landowning elite emerged in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. This elite relied on family strategies to maintain itself economically and to guarantee its political power. By marrying their daughters to wealthy merchants, landowners bought themselves new capital. Marriages to powerful royal officials gave them influence. Family life in colonial Brazil, as in Spanish America, was critical to the formation and perpetuation of the elite.[8]

The behavior of elite families in Parnaíba similarly affected the evolution of a socially stratified town. Because wealthy families owned valuable resources of land and labor, how these families acquired property, held it in their families, and distributed it to their heirs affected not just their own families but the community as a whole. The dominance of elite families in local institutions—the town council, militia, and church likewise contributed to social inequality. Such institutions reflected the interests of the elite, not those of the whole population, and thus served to reinforce the power of wealthy families.

As a few families successfully concentrated resources into their own hands and influenced local institutions to their advantage, they helped to create and reinforce social classes. The social world of Parnaíba was stratified in many different ways. Wealth, race, family ties, age, sex, and marital status all influenced how the townspeople perceived themselves and each other. Yet, increasingly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, three social classes evolved in Parnaíba: planters, peasants, and slaves. Planters owned land and slaves and produced commercial crops, such as sugar, for sale. Peasants owned no slaves and primarily produced food crops for their own use and for local markets. Slaves had few resources beyond what they received from their masters. The majority of slaves did not own anything, not even their own labor. Each class had a unique relationship to the principal resources needed for survival in the town land and labor. Each

class had fundamentally different family lives. Each class interacted with the frontier in distinct ways.

Any typology invariably oversimplifies the social world experienced by individuals. In Parnaíba, a family with one slave was hardly much better off than a family without any slaves. Similarly, a freed slave who continued to serve her former master probably did not experience a radical life change from what she had known as a slave. Yet in terms of how families perceived themselves, it did matter to a former slave that freedom had been purchased, awarded, or promised. To a poor family with one slave, the possession of that slave accorded a status in the community that families without slaves did not have. Thus, while the boundaries between social classes might seem crude, they do serve to define the ranks of Parnaíba's society. In that society, the lives of planters (who owned slaves) differed fundamentally from the lives of peasants (who did not), and the lives of slaves similarly diverged from those of peasants and planters.

Historians of colonial Brazil disagree over what terminology to use to characterize the social structure of the colony.[9] Some argue that the colonial world was a society of castes; others, that it was a society of classes. Still others prefer the concept of estates. The proponents of the term "estate" borrow it from old regime France, which was divided into three estates: those who prayed (clergy), those who fought (nobility), and those who worked (peasants, artisans, the bourgeoisie). The term "caste" derives from studies of India wherein individuals were born into a caste and remained in it all their lives. I use the term "class" because it best describes the historical reality I find expressed in the sources. "Estate" does not rightly characterize a society that had no titled nobility, a weak clergy, and a large number of slaves. "Caste" implies a rigid society with no social mobility, yet the extensive ties to the frontier provided the residents of Parnaíba with such avenues. Even slaves could obtain their freedom. In contrast, "class" suggests a society in which large groups of people are differentiated by their relationship to material resources. Planters possessed land and labor; slaves did not. Peasants owned more resources than slaves, but fewer than planters. These simple facts increasingly differentiated the lives of individuals in the seventeenth and eighteenth cen-

turies. Thus, I conceptualize Santana de Parnaíba as a class society composed of planters, peasants, and slaves.

Family life varied by class. Families of the planter elite lived in large hierarchical households where the interests of many had to be subdued and conflicts avoided. The importance of property in maintaining their status meant that family customs explicitly regulated events such as marriage and inheritance. These customs worked to keep women from wanting independent lives or from marrying the men of their choice. Other customs worked to minimize conflicts between brothers. Similarly, the paternalistic and benevolent ways in which these families treated their slaves and other servants served the very important function of smoothing over the inequalities that existed in such households.

For the peasantry, family life revolved around the cultivation of small plots of land by family members. They had to cooperate with each other and share in the work that provided the sustenance for all. The vast majority of these families lived in small nuclear households composed of parents and their children. Mothers and fathers taught their children how to work in the fields and in the house from a young age. These families valued cooperation between men and women, brothers and sisters, and families and neighbors.

Slave family life differed substantially from that of planters or peasants. Slavery afforded little room to create autonomous family lives. The economic fortunes of masters and the attitudes of masters toward slave families determined many aspects of slave family life. Other factors, such as the demographic characteristics of the slave population or the size of the estates on which slaves lived, also influenced the chances that slaves would marry and form families. Slave families tended to be less stable than those of planters and peasants because of constant change, occasioned not just by marriage, birth, or death but by transfer of ownership. Thus, of the three social classes of Parnaíba, slaves had the least control over their family lives.

Not only did family life vary by class but each class interacted with the frontier in different ways. Families of planters saw their survival in terms of acquiring property from the wilderness frontier and preserving it for future generations. This property could be land, Indian slaves, or gold. Moreover, when these families divided their property each generation, they expected some of their

children to migrate west. Thus, they favored some heirs at the expense of others by allowing the favored heirs to inherit the bulk of the family resources and the social position of the parents in Parnaíba, knowing that other children would make their fortunes in the frontier. Heirs who remained in Parnaíba but were not favored paid a price: downward social mobility. They became small planters with few resources. Such customs of family life among the planter elite promoted the development of the frontier, maintained large agricultural estates in Parnaíba, and created a growing substratum of the planter class composed of poor planters.

The peasantry also relied on the frontier for their survival. Primarily, they desired land to provide for themselves and their children. But because they often lacked the ability to protect their lands over time, they moved on with the frontier. These peasant farmers became the first wave of frontier settlement, often battling with Indian tribes for virgin forest to clear and plant. Those peasant families who were able to retain their lands in Parnaíba turned their attention to the developing city of São Paulo, which they furnished with their food surpluses and in which they worked as mule drivers and laborers. Many of the young men and women from peasant families migrated to the town center to become artisans or servants, and to the city of São Paulo.

Although some slaves did escape to the frontier where they formed runaway slave communities (quilombos ), and many others were taken to the frontier to cultivate new sugar and coffee estates, the majority of slaves did not see the frontier as a place they might use to their advantage. Beyond running away to the frontier, slaves devised no strategies to exploit it. Their strategies for the survival of their families and kin networks developed in Parnaíba and its immediate environs, where they formed a black community. Slaves sought privileges from their masters which might make their lives more bearable. This might take the form of the right to plant a garden, the right to save for purchasing their freedom, or the fight to marry a free person or a slave from a neighboring estate. Slaves formed religious brotherhoods with other slaves and free blacks; these associations created the basis for a black community in Parnaíba. Slaves thus devised their family lives in a very different context than the slave-owning planters or the slaveless peasants.

To summarize, frontier family life in this region of colonial Brazil developed in several contexts. First, family life varied for each social class. Second, families perceived the frontier in diverse ways and used it accordingly. Third, the frontier had a dissimilar impact on the families of each social class. Families of planters, for example, used the frontier to their advantage; slaves generally did not.

Through their varying strategies for survival, families participated in and reinforced the formation of social classes in Parnaíba. The resulting structure of power and authority reproduced itself in this community over many generations. The social structure of the community was neither preordained nor imposed from afar. Rather, it evolved as colonists in this region of the Portuguese empire made choices about how to live in and interact with the empire, choices that would shape the community inherited by their children and by their children's children.

Through the study of a small and ordinary town, a wide variety of issues, events, and processes characteristic not only of Brazil but of the Americas during the great age of colonization can be examined. The intent of this study is not to elevate the importance of this town but to use it as a lens so that one process of colonization can be magnified and revealed in detail. Since the different character of colonization in the Americas has produced very different results, an understanding of modern American societies must rest on an analysis of their colonial roots. The history of Santana de Parnaíba helps us to understand the historical roots of modern Brazil, especially the region dominated by São Paulo, the industrial, financial, and technical hub of Brazil today, and its modern frontier, the western Amazon basin.

To write the history of colonization from the point of view of the people who lived it is not easy. The vast majority of the people who lived in Santana de Parnaíba did not read or write. Many did not even speak Portuguese very well. Because Santana de Parnaíba did not interest the Portuguese kings or their Brazilian governors, they sent few officials to this community to observe the people and to write about them. The sources that historians traditionally have used thus do not exist. But the history of this community can be written and the contributions of its people to the colonization of Brazil assessed because many other sources do exist which can be developed by historians.

Many diverse sources, pieced together, reveal glimpses of Santana de Parnaíba as it evolved over time. The most important sources for this study are the manuscript censuses that capture, as in a snapshot, the entire population at one moment in time. From the census, it is possible to calculate a demographic profile of the population that would include such factors as its size, its age structure, and the ratio of women to men. Because the censuses of the second half of the eighteenth century for the state of São Paulo are so exceptionally detailed, historians can see clearly who lived in each household, what families planted on their farms, and the composition of the labor force. From this information, it is possible to define the social classes that inhabited the community. Unfortunately, the censuses only exist for the late eighteenth century, when the region of São Paulo caught the attention of the crown's ministers because of its strategic location close to the Spanish colonies of the Rio de la Plata. The officers of local militia, ordered to canvass their districts beginning in 1765, conducted yearly censuses until the 1840s. Three of these censuses, those of 1775, 1798, and 1820, provide the statistical backbone of this book.

The property inventories and wills from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Santana de Parnaíba are the second major source for this study. This collection includes several hundred manuscript and published inventories and wills. Through the analysis of the inventories, it is possible to reconstruct the material culture and the inheritance customs of the people. The inventories of property, conducted after the death of an individual according to Portuguese law, meticulously recorded every item owned by the deceased. Perhaps the most important part of the inventory was the division of property (the partilhas ) among the legal heirs, which was carefully recorded in these documents. Some of the inventories included wills dictated by men and women who wished to record certain last wishes to be carried out after their deaths. These wills are an especially rich source of information on individual lives, family ties, community life, religious customs, and family property.

The wills and inventories document the many changes that took place in Santana de Parnaíba over two hundred years, but they do have their limitations. One major flaw is their bias in favor of the wealthy. People who did not own property did not need to inven-

tory it; nor did they have the opportunity to summon a notary to whom they might gasp, in their dying breaths, their last testament to the living. Sometimes the poor can be glimpsed in the wills and inventories, as for example when bequests were left to the destitute. Slaves can be traced through inventories because as property, very valuable property, they always appeared in them.

Parish registers of births, marriages, and deaths kept by the priest of one parish, Santana, through the eighteenth century are another source extensively used in this study. Parish registers, like the censuses, include the whole population, not just the wealthy. Records of marriages and baptisms are used not only to calculate the rate of marriage or the fertility of women but to understand how families linked themselves to others. Since at marriage and at baptism, godparents and witnesses presented themselves, such records provide important clues to how families constructed their wider world of relations and acquaintances.

The town council of Santana de Parnaíba kept a huge volume of records on local government, many tomes of which are preserved in the state archive of São Paulo. Of special import to this study are the notary books that list land sales, slave sales, and slave manumissions. The records of cases brought before the local justice of the peace are especially interesting because they contain the testimony of individuals on a variety of conflicts that erupted in the town. The ledger of the jailer recorded every prisoner sent to the jail in the second half of the eighteenth century. Finally, communications from royal officials, the letters of Jesuit priests, maps, and genealogies of prominent families have all been used to reconstruct the history of this community and the people who lived in it.

Although the innermost thoughts of the people of Parnaíba are rarely recorded, the sources do allow the historian to reconstruct the outward characteristics of individual and family life. For this reason, this book describes behavior rather than thought, the exterior rather than the interior. But even if such introspective sources did exist, one of the central tenets of this work is that the family strategies used to survive and succeed in Parnaíba were not always conscious; rather, they were part of the unacknowledged and even unquestioned way of living. Thus, the behavior of fami-

lies as a group, is, in this analysis, more important than the thoughts of individual members.

The methodology of this study was designed to reconstruct the evolution of the community over time while also analyzing in detail the relationships among individuals, families, and social classes at particular moments in time. Thus, the study has both a horizontal and a vertical dimension. Many of the sources yielded information on both axes. A single census, for example, provides a plethora of information on households in the population and the class structure of the community at one point in time, while the study of three censuses at fifty-year intervals reveals the changes in household and class structure over time. The methodology also incorporates both quantitative and qualitative sources. The censuses, the parish registers, and the property inventories lend themselves to quantitative analysis. Easily coded for computer manipulation, they can reveal certain statistical characteristics of the community—its size, class structure, economic character, and demographic profile—as these change over time. The statistical analysis of these sources creates the framework for the qualitative analysis of other sources, such as wills, testimonies, and letters, which provide information that helps to explain the patterns found in the quantitative analysis. For more detailed information on sources and methodology, see the Appendix.

The units of analysis for this study are family, class, and community. Family is the most basic unit of analysis. The term is, however, difficult to quantify. In censuses, the "family" appears as a group of individuals living together at the moment of the canvassing, but in a will or an inventory, the "family" refers to a larger group of related kin. For this reason, demographers and family historians distinguish between the household and the larger family.[10] The household refers to the individuals who actually live together at one moment in time, while the family encompasses a wider group of individuals, such as those who have left home, relatives, and biologically unrelated kin. For quantitative analysis, the delineation of households in a census defines at the most basic level what a family is, but the broader sense of the term is also employed. This is especially true in the qualitative analysis.

Here family life has been evaluated within the larger context of

social class. Social classes, which gradually emerged during the seventeenth century, eventually differentiated the community and came to create a vast distance among the family lives of the people. Because slaves were the most visible and valuable measure of status and wealth, the ownership of slaves is used in the quantitative analysis to demarcate the boundaries between social classes. Thus, the dividing line between peasant farmers and planters is the ownership of slaves.

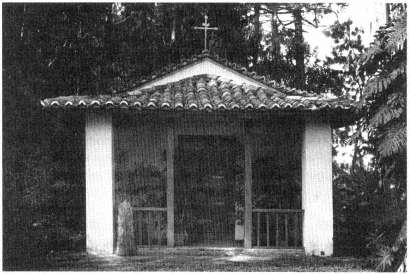

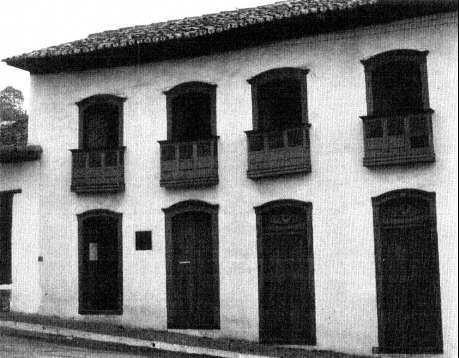

The third level of analysis in this study is the community, Santana de Parnaíba. In the early seventeenth century, Parnaíba became a vila , a term difficult to translate into English. Literally "town," in actuality it encompassed a large rural area composed of four parishes. In the original settlement, which became the parish of Santana, stood the administrative institutions of the town—the town council (câmara ) and the mother church (igreja matriz ). Residents of the community conducted their business here, and for that purpose, the most important families built town-houses. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the parishes of São Roque and Araariguama sprang up around large estates. Baruerí was the site of an Indian community founded in the early years of the seventeenth century. In the eighteenth century, São Roque and Araçariguama grew steadily. By the nineteenth century, these two parishes had become large enough to be cut away from Parnaíba and become independent municípios (municipalities) after Independence. São Roque and Baruerí, now both on the railroad line, have become small cities, while Parnaíba and Araça-riguama (not on the railroad) have remained sleepy rural towns despite their proximity to the burgeoning city of São Paulo. Today, Santana de Parnaíba refers only to the old parish of Santana and is therefore much smaller than the community studied in this book. Thus, community here does not refer to a closely knit hamlet of a few families but to a rather large rural area that had a common administrative center in the original settlement, the parish of Santana.

When writing a social history based on the experience of a single community, historians and their readers must ask themselves a very important question: How typical is this community? Stated otherwise, how useful is this detailed history for understanding the experiences of larger groups of people? The work of North

Town of Santana de Parnaíba

American historians on colonial America is especially instructive for answering this question. Beginning in the 1970s, the history of colonial America was revolutionized by the appearance of two community studies on the New England towns of Dedham and Andover.[11] These studies sought to show in concrete detail how the Puritan colonists put into practice their religious ideas; historians Lockridge and Greven turned their attention from what the Puritan religious leaders thought and preached to how the families of Dedham and Andover actually constructed their communities. Lockridge found that Dedham in its early years was a closed corporate community bonded by shared religious beliefs that expressed a utopian ideal. Life in Dedham was better than life in Europe had been: mortality was low, inequality less pronounced, and the farming economy adequate for the sustenance of the community. Later, Lockridge argues, the utopia ideal died in Dedham as the community grew, as land became scarce, and as younger generations lost the religious fervor of the town's founders. The closed agrarian world of the seventeenth century gave way to a more complex, provincial town in the eighteenth century.

Greven also found continuity between England and America in the early history of Andover and a substantial change from the seventeenth to the eighteenth century. In the first two generations, Andover resembled an English village. A strong patriarchal family had taken root, and fathers maintained control over their sons by withholding land from them until late in their lives. Like Lock-ridge, Greven characterizes these early years as times of stability and order. Compared to England, individuals lived longer and women had more surviving children. In the third and fourth generations, these patterns changed as sons began to challenge their fathers' authority. Many left the community in search of lands elsewhere.

These two studies, with their characterization of the seventeenth century as a time of order, harmony, stability, and prosperity and the eighteenth century as a time of growth, change, lessening community values, and greater individualism, dramatically influenced the work of later historians of colonial America.[12] The transformation of a closed agrarian, relatively harmonious world into an open, commercial, individualistic, and conflict-ridden world seemed to lay an appropriate foundation for the explanation of the American

Revolution at the end of the eighteenth century. But as more historians began to adopt the community study approach of Greven and Lockridge, their results diverged. Stephen Innes's Springfield, Massachusetts, a river town founded in 1636, never resembled the closed, corporate, utopian communities of Andover and Dedham. In his introduction, Innes notes, "few historians have ... queried whether the experiences of Dedham and Andover really typified early New England. Particularly striking is the willingness to generalize with such confidence from the examples of two subsistence farming communities, especially since ... [t]he majority of seventeenth-century New Englanders lived either in ocean ports or in major river towns."[13] Innes documents that materialism, not spiritual unity, characterized Springfield, where men were judged more often by their financial worth than by their piety. Artisan crafts, manufacturing, commerce, and agriculture created the base of the economy of the region. Springfield, hardly a utopia, fostered conflict, violence, and social inequality. One family monopolized the resources of the community and dominated its political institutions. And whereas Andover and Dedham became more individualistic and stratified in the eighteenth century, Springfield became less so as the American Revolution approached.

Innes's study of Springfield thus seems to contradict in virtually every way the picture of life in Andover and Dedham painted by Lockridge and Greven, even though the towns in question are all from the same region and indeed the same state, Massachusetts. Which is the more accurate description?

Gradually, what has emerged from this fascinating literature is an awareness of the importance of regions in colonial America. Innes argues that Massachusetts alone had three distinct regions: an urban coastal region with its center at Boston; a surrounding subsistence farming region (in which Andover and Dedham were to be found); and a third area of commercial agriculture in the Connecticut River towns, such as Springfield. Each region, he argues, "had different patterns of social relations, economic opportunity, and political behavior."[14]

If Massachusetts has to be studied in terms of its distinct regions, all the more important is the distance between New England and the communities that emerged in the American South. There the environment, economy, and social institutions such as indentured

servitude and African slavery created very different communities. Historians have found that the high mortality rate in seventeenth-century Maryland, due largely to malaria, coupled with the influx of immigrant indentured servants, most of whom were men, created dramatically different patterns of family life. In a society where 70 percent of men would die before the age of fifty and where men outnumbered women by three to one, spinsters married and widows remarried quickly and easily. "Blended" families were formed, composed of stepchildren from previous marriages and new children. Because of the high death rate, thousands of children became orphans and wards of community institutions.[15]

Unlike their northern counterparts, southern communities were not rent with conflict between fathers and sons because the adult lives of fathers and sons rarely overlapped. When fathers did live to see their sons to adulthood, they transferred property and authority to them at a young age.[16] As Lorena Walsh argues, families in New England successfully transferred a patriarchal family structure to their communities, but in the Chesapeake, they could not.[17]

The very different pictures of community life in colonial America has led to much questioning of the genre of community studies. A proponent of the method himself asks, "Collectively do they add up to anything?"[18] This same scholar submits that despite the many different panoramas of life in America that the studies depict, there are some common features. Almost everywhere the fundamental social institution was the nuclear family, which survived by farming. Families tended to form long and lasting ties to their neighbors, with whom they cooperated in order to survive. The pace of life was slow, and the large events of history "crept upon the towns and counties all unawares."[19]

Jack Greene further proposes that it is possible to integrate the findings of diverging community studies to reach a synthesis. In Greene's view, the first settlements in the New World were disorderly because colonists had a hard time adapting their European culture to the American environment. But slowly, as the settlements grew, they became stabler, more orderly, and more complex. By the eighteenth century, elites consciously began to try to replicate British society in their lives and communities. For Greene, the progression of development in colonial America followed the patterns found by historians in the Chesapeake rather than those

of New England. Moreover, American societies became more, not less, like Europe over time.[20]

Greene's "developmental model" and the community studies of the Chesapeake are particularly evocative for colonial Brazil. Colonial Brazil held much in common with the U.S. South. The formation of cash-crop agricultural economies based on slave labor and the creation of sharply stratified communities are characteristics shared by both. Like the towns of the Chesapeake, the residents of Santana de Parnaíba did not share a common dream of religious utopia. The study of this town reveals not the genesis of a community united by religious ideals but the birth of a town rent with social inequality.

As has occurred among historians of colonial America, historians of colonial Brazil also question the significance of a single interpretation or model for understanding the past. For decades, the portrayal of Brazil's colonial past has been dominated by the work of one anthropologist, the late Gilberto Freyre. Freyre characterized the colonization of Brazil as a process in which a plantation society typified by miscegenation took root. In this process, it was the family, not the individual, the state, a commercial company, or the church, that played the major role. The family was "the great colonizing factor in Brazil, the productive unit, the capital that cleared the land, founded plantations, purchased slaves, oxen, implements; and in politics it was the social force that set itself up as the most powerful colonial aristocracy in the Americas."[21] For Freyre, colonial society evolved in the casa grande , the big plantation house, the seat of the colonial aristocratic family, and in the senzala , the slave hut. In the big house, families were large, extended, and patriarchal. The slaves of the huts outnumbered the whites of the big house and transmitted to them much of their African culture. Surrounding the plantation, but dependent on it, lived a racially mixed but marginal population of free men and women. While Freyre recognizes that this model of colonization principally characterized Pernambuco and the Recôncavo of Bahia, he argues that wherever sugar cultivation spread in Brazil, "there grew up a society and a mode of life whose tendencies were those of a slaveholding aristocracy, with a consequent similarity of economic interests."[22] Because sugar cultivation and slavery did dominate Brazil's colonial economy in the sixteenth

and seventeenth centuries, and continued to spread during the great gold rush of the eighteenth century, historians have used Freyre's model of colonization to characterize colonial Brazil.[23]

When social historians in Brazil, influenced by the work of European historical demographers, began to study the family, they uncovered startling evidence that Brazilians had not, by and large, lived in the great families described by Freyre. The analysis of censuses for the city of São Paulo in the second half of the eighteenth century and for the city of Vila Rica in Minas Gerais in the early nineteenth century reveal few large extended families. In São Paulo, Elizabeth Kuznesof found that nuclear families predominated and that households were small. Households headed by women became increasingly common as the city grew, accounting for 45 percent of all urban households in 1802.[24] In Vila Rica, Iraci del Nero da Costa found that likewise very few, less than 10 percent, of the households were extended or complex households in 1804. Forty-four percent conformed to what Peter Laslett calls the simple family (a household of one or both parents and children), and a surprisingly high number (39%) of the households were formed of single or widowed individuals living alone or with retainers or slaves.[25] Donald Ramos, analyzing the same census, was struck by the large number of households headed by women.[26] At first glance, this high number of female-headed households appeared to be explained by the fact that they were an urban phenomenon: the cities attracted poor women who survived there as artisans, servants, street sellers, and seamstresses.[27] But on closer analysis, female-headed households were also found in the rural areas.[28] Even in rural Bahia, family historians confirm the existence of female-headed households.[29]

These findings, so incompatible with the traditional image of the Brazilian family, have caused scholars to question seriously Freyre's model of the large, extended, patriarchal family as the Brazilian norm.[30] But while historians are willing to agree that the characteristic family of Brazil was not the extended patriarchal family envisioned by Freyre, not all are willing to give up Freyre's model as a description of elite families. They intimate that while Freyre's family type is inappropriate for the majority of the population, it may well characterize the family life of the upper classes.

Two scholars who do not entirely reject Freyre's portrait of the

family are Linda Lewin and Darrell Levi, who studied two influential families in nineteenth-century Brazil, the Pessoa oligarchy of northeastern Paraía and the Prado family of São Paulo.[31] While neither of these historians argues that Freyre's description of the family is accurate, nor do they employ the demographic analysis of households favored by historical demographers, they clearly illustrate the importance of the elite family's extended and intricate kin network. Colonial Brazilians may have lived primarily in nuclear families, Lewin and Levi imply, but the larger kin network deeply affected family life and is key to their social and economic power. From these two studies, it would appear that such extended kin networks, which are not usually visible in censuses, are crucial to the understanding of elite families.

Demographic analysis of elite families based on manuscript censuses, however, suggests that Freyre's model must be used with care, even when applied only to elite families. Ana Silvia Volpi Scott[32] illustrates that nuclear families predominated among the elite of São Paulo, accounting for 60 to 75 percent of all elite households between 1779 and 1818. Family size was small: 6.3 members in the towns of the Paraíba River region and 4.7 members in the towns of the region of and around the city of São Paulo. Because Scott bases her analysis on families as they appear in the manuscript censuses, she is unable to establish the kinship ties of families from her data. But if it were possible to combine a demographic analysis of elite families with family histories like Lewin's or Levi's, such analysis might reveal that the extended, patriarchal, elite family proposed by Freyre was not a demographic fact but rather a description of elite family kinship relations. Further studies on elite families that combine a demographic analysis with a social and economic inquiry into elite family life will eventually allow historians to describe accurately the elite family in Brazil.[33]

Before rejecting Freyre's family model, historians must consider change over time. Elite families may have been more extended and more complex in the first centuries of colonization—that is, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—than in the nineteenth century. While the most reliable demographic data exist for the late eighteenth century and the nineteenth century, historians must not assume that patterns of elite family life found then characterized the whole of the colonial period.

But what of the family lives of other social groups in colonial and nineteenth-century Brazil? Slowly, historians are fashioning a picture of the urban poor, a group whose demographic history points to very high levels of female-headed households, illegitimacy, and consensual unions.[34] Clearly this population did not live in or even near the large extended families portrayed by Freyre. While historians have come a long way in documenting the demographic contours of this social group, very little is known about the families of the rural poor in the historical past. Maria Luiza Marcílio's path-breaking study of the peasant farmers and fishermen of the coastal village of Ubatuba in São Paulo begins to define the family lives and survival strategies of Brazil's peasantry. As she shows, peasants in their traditional life-style successfully used the labor of family members to support themselves and to interact in local economies; but lacking political power, they proved unable to retain their lands as agriculture commercialized.[35] This pattern, also found in Parnaíba, may well be a common characteristic of the peasantry throughout Brazil.

Spurred by the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Brazil, many new studies on the slave family have been undertaken there. But, given the fact that slavery existed for over three hundred years in Brazil in regions as diverse as that of the sugar-producing northeast, the mining regions of the interior, or the Amazon River, historians are a long way from defining "the slave family." Clearly slave life differed in these distinct areas and changed over time. In the cities, for example, slaves had more independence and autonomy but less stable family lives.[36] In the countryside, slaves had little autonomy, but because many lived on large plantations, they were able to form nuclear and extended families that endured over time.[37]

Thus, the work of many historians on Brazilian families has forced scholars to seriously qualify the universality of Freyre's vision of the Brazilian family in the past. As more and more studies are completed, it will become possible to come to a synthesis of what family life was like in colonial Brazil. This book works toward that goal by studying family life in the context of social class, the larger community, and the frontier.

The study of family life in Santana de Parnaíba reveals that the roots of inequality in this community stem from the way that

families interacted with the frontier. Virtually all families of the free population in Parnaíba in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries depended on the resources of the frontier for their survival. Those families that exploited the frontier for a larger Atlantic economy became part of the planter class and renewed their wealth each generation by continuing the exploitation of the frontier. Those families that depended on the resources of the frontier for the survival of their immediate family became part of an independent but ultimately vulnerable peasantry. Slaves, prevented from sharing in the wealth of the frontier, remained at the bottom of the social ladder. These conclusions suggest profound questions about how family strategies in colonial Brazil have influenced the evolution of a stratified social order in this American frontier society.

1

Indians, Portuguese, and Mamelucos

The Sixteenth-Century Colonization of São Vicente

In 1628, the lady widow Suzana Dias lay sick in her bed in her son's house in a tiny hamlet known as Santana de Parnaíba. The village was located on the edge of the Brazilian wilderness, several leagues to the west of the town of São Paulo. Fearing her death, Suzana summoned a scribe to her bedside to record her last will and testament and a priest to perform the last rites. First, she asked the priest to "commend her soul to God our Lord who created her" and prayed that "through the death and suffering and worthiness of his Son our Lord Jesus Christ, that he have mercy on her soul and pardon her sins." She begged for the intercession of the Holy Virgin, the apostles, and all the saints before God so that she might attain the rewards of glory.[1] Suzana declared that she believed in everything that was and is the Holy Mother Church of Rome and that she would die a loyal and true Christian. Then, having taken care of salvation, she turned her attention to her temporal life, to the family she had reared, the property she had accumulated, and the settlement she had founded on the remote edge of the Portuguese empire.

Suzana had married twice and bore seventeen children. She owned Indian slaves who served her and who would serve her heirs after she died, even though as she herself knew, these Indian slaves were legally free according to the laws of the Portuguese empire. A shawl, a skirt, a cloak, and the material for a skirt were important enough to be mentioned in her will as special bequests for her daughters and granddaughters. Suzana asked her two sons to have thirty masses said for her soul "so that God Our Lord might have mercy on her" and stated that she wished to be buried in the chapel of St. Anne that she had founded and around which the

settlement had grown. Last, she asked the priest to sign the will for her, as she did not know how to read or write.

This seemingly simple document marks the end and the beginning of the history of Santana de Parnaíba. When Suzana Dias was born, Santana de Parnaíba did not exist. The area was wilderness, as yet unsettled by the Portuguese or by those of Portuguese and Indian descent, known as mamelucos . By the time Suzana died, however, the Portuguese had claimed and colonized this area of the wilderness.

Who was Suzana Dias? According to historical and genealogical reconstruction, she was one of the granddaughters of Tibiriá, the Indian chief of the Piratininga plateau when the Portuguese first landed on the coast of Brazil in 1500.[2] ç The Piratininga plateau, site of modern São Paulo city, is nearly 800 meters above sea level. It is drained by the Tietê River, which flows west, deep into the interior, to the Paraná River. The climate is mild, with an average temperature of 68.4 degrees Fahrenheit and an average rainfall of 52.2 inches per year.[3] Tibiriçá first met the Portuguese through João Ramalho, a Portuguese sailor or convict who had been shipwrecked or dumped ashore during the early years of the sixteenth century, probably between 1511 and 1513.[4] Although Tibiriçá could not know what his encounter with this Portuguese castaway portended, it was the first step in a long chain of events that would radically transform the world he knew.

In Spain and Portugal, the last years of the fifteenth century and the first years of the sixteenth century were heady times. When Christopher Columbus "discovered" islands in the Caribbean in 1492, Portugal was on the verge of achieving a long-sought sea route to India. In anticipation of this, in the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494, Spain and Portugal divided the non-Christian world in half, with the east going to Portugal and the west to Spain. Six years after Columbus's attempt to reach India by sailing west, the Portuguese explorer, Vasco da Gama, rounded Cape Horn and sailed into India. In 1500, Cabral set off for India intending to lay the foundation for trade between India and Portugal. Cabral set his course slightly different from that of Vasco da Gama, and blown farther west, he reached Brazil by accident. Unlike Columbus, Cabral had not left Lisbon on a voyage of discovery and did not have any rights to lands that he might discover. The discovery of

Brazil thus held no immediate reward for him. He would not become the viceroy and governor over any lands he discovered, nor would he be known as the "Admiral of the Ocean Sea," privileges promised to Columbus by Ferdinand and Isabella.[5] Instead, this remarkable discovery was treated as an unexpected delay on the more important voyage to India. Far more interested in the opening of trade to India, the Portuguese made no immediate plans to explore or colonize Brazil, although it clearly lay within Portugal's sphere, according to the treaty.

Cabral remained in Brazil only eleven days, but the first Portuguese impressions of Brazil were captured by Pedro Vaz de Caminha, a royal clerk on the expedition bound for Calicut. In a letter written to the king of Portugal, Caminha described a vast new land and people of "good and of pure simplicity." "From point to point," he wrote, "the entire shore is very flat and very beautiful. As for the interior, it appeared to us from the sea very large, for, as far as the eye could reach, we could see only land and forests, a land which seemed very extensive to us."[6] He described the inhabitants of this land as "dark, somewhat reddish, with good faces and good noses, well shaped. They go naked, without any covering; neither do they pay more attention to concealing or exposing their shame than they do to showing their faces."[7] Caminha marveled at the innocence and beauty of the Indians. He wrote, "They are well cared for and very clean, and in this it seems to me that they are rather like birds or wild animals, to which the air gives better feathers and better hair than to tame ones. And their bodies are so clean and so fat and so beautiful that they could not be more so."[8]

Caminha's observation of the Indians convinced him that they had no religious beliefs and that they could be easily "tamed" and "stamped" with "whatever belief we wish to give them."[9] While Caminha saw the possibility of using the new land for agriculture, he thought the evangelization of these people would, in and of itself, be a noble achievement for the king of Portugal to undertake, even if the new land proved to be not much more than a stopping place on the way to India.

Caminha finished his letter on May 1, 1500, the night before the fleet set sail for India. That day, two sailors stole a boat and deserted from Cabral's command, disappearing somewhere along

the coast. In addition to these, Cabral left behind two prisoners to learn the Indian language to facilitate further encounters with the Indians, should there be any. Then without further ado, Cabral weighed anchor and headed east for Africa and India. Caminha's letter, along with the parrots, bows, arrows, headdresses, and the like, collected from the new land, were sent directly back to Portugal on one of the ships of the fleet. Perhaps no one who witnessed this simple eleven-day visit realized how dramatically it would change the future of the land the Portuguese now called "Santa Cruz."

At the moment when Spain and Portugal first made contact with the vast New World, each country had very different ideas about how to proceed with colonization. The Spanish had completed the work of centuries, known as the reconquest, when they defeated the Moors of Granada in 1492. The marriage of Ferdinand of Aragón and Isabella of Castile began the process of the unification of Spain. The religious zeal with which the Spaniards conquered the Moors and allotted their lands to military commanders overflowed into the New World. Spain embarked on a similar quest to spread Christianity, to make vassals of the Indians, to reward the conquerors who delivered this new empire, and to strengthen the power of the crown.[10]

Portugal was a trading nation that for decades in the fifteenth century had pioneered the navigation of the southern Atlantic and the charting of the African coast in pursuit of a sea route to India. The Portuguese sought to enter the profitable spice trade from the Orient, a trade completely controlled by Arab traders across land routes through the Middle East. In 1498, they succeeded in establishing the long awaited sea route, and thus for the first time, Europeans had direct access to the spice trade.[11] Cabral's discovery of Brazil, therefore, was treated differently in Portugal than Columbus's discovery was treated in Spain. Portugal saw the value of trade with the newly discovered natives of Brazil, not colonization. For this reason, Portugal made no immediate plans to colonize Brazil.

For thirty years after the discovery of Brazil, from 1500 to 1530, the Portuguese saw Brazil as simply another entrepôt, similar to the many trading posts along the coast of Africa where Portuguese ships stopped on the way to and from India to trade for slaves. At

the few coastal trading posts in Brazil, the Portuguese traded with local Indian tribes for the pau brasil , or brazilwood, a tree trunk much in demand in Europe because of the deep red color that could be extracted from it and used to dye cloth. Each of the trading posts had a factor and a small garrison of soldiers to protect it. The factor conducted trade with the Indians, bartering iron tools, combs, mirrors, beads, and the like, for brazilwood. The Indians cut, carried, and stacked the logs at the trading post so that cargoes would be ready for ships to load when they put into port.

The Portuguese were not the only ones to trade in Brazil. The French were also active in the brazilwood trade, arguing that since Portugal had not colonized Brazil, she could not prevent others from trading with the Indians. Thus, while Portugal claimed Brazil by virtue of Cabral's discovery, she exercised virtually no sovereignty over it.

During these early years of the sixteenth century, only a handful of Europeans, like João Ramalho, lived in Brazil. Convicts left ashore by sea captains, shipwrecked sailors, and the factors who manned the small trading posts were the only Portuguese there.[12] Many went "native" to survive. Such was the case of Ramalho.

Men like Ramalho adapted to a radically different world than they had known in Europe. The huge area of Brazil, covered largely by forests, was sparsely inhabited by hundreds of Indian tribes. While it is difficult to estimate the size of the Indian population of Brazil in 1500, John Hemming presents a reasoned estimate of 2.4 million.[13] These tribes belonged to four major language groups: the Tupi, the Gê, the Carib, and the Arawak. The Tupi lived primarily along the Atlantic seaboard, the Gê lived in the central plateau, the Arawaks inhabited the upper Amazon, and the Caribs lived in the lands to the north of the lower Amazon River delta. Despite differences among these major groups, the Indians of Brazil shared some common lifeways. They lived in independent tribes composed of several villages ruled by councils of elders, chiefs, and shamans. They fed themselves by hunting, fishing, gathering fruits and other edibles, and simple agriculture. In small clearings made by cutting trees and burning the brush, they planted the basic staples of their diet: corn, manioc, pumpkins, beans, squashes, and peanuts. A clear division of labor separated men and women: the men hunted, fished, and fought, while

the women farmed, prepared the food, and cared for the children. The tribes moved their villages frequently to take advantage of new hunting grounds and new land for farming. Possessions were few, easily packed, and carried on tribal migrations. Compared to the large and complex Indian civilizations of central Mexico and Peru, the Indian tribes of Brazil were mobile, autonomous, and egalitarian.[14]

Among all tribes, but especially among the Tupi, warfare was a common occurrence and an unquestioned part of tribal life. Competition over hunting grounds often sparked intertribal wars. Among the Tupi, intertribal feuds caused a virtual state of war between hostile tribes, such as that between the Tupiniquin and the Tupinambá. These wars often began over the need to avenge the honor of the tribe because of atrocities committed against them in the last war. Usually these insults centered on the practice of ritual cannibalism, committed with prisoners of war. In an elaborate ceremony, prisoners were killed and their flesh "tasted" by the tribe. In return, the tribe of the prisoner would retaliate by performing a similar ceremony with a prisoner from the guilty tribe. This created an unending cycle of warfare between the Tupi Indians.[15]

Because few Portuguese lived in Brazil during the thirty years following Cabral's discovery, the vast majority of the Brazilian Indians had little contact with the Portuguese. Those who did either assimilated individual men or had limited, intermittent contact with the traders. On the Piratininga plateau, Ramalho became a part of the extended family of Tibiriá. He married one of the chief's daughters and became a respected and powerful member of the tribe. Since the Portuguese did not establish a trading post near Piratininga, Tibiriçá's people did not go to work for the Portuguese cutting brazilwood.

This isolation changed in 1530 when, concerned over the increasing interest in Brazil by French traders, the Portuguese king directed Martim Afonso de Sousa to establish Brazil's first colony. Martim Afonso's expedition, charged with patrolling the coast of Brazil and exploring the southern coast in addition to founding a colony, left Portugal toward the end of 1530. Royal officials, soldiers, priests, gentlemen, mechanics, laborers, settlers (some with their wives), and sailors made up the expedition, which numbered about 400 persons and four ships. Martim Afonso sailed along

the coast of Brazil attacking French ships before heading south to establish a colony. He selected an island at a latitude of 24º30" and there ordered his men to erect a fort and construct the rudimentary beginnings of Brazil's first colony, São Vicente. Leaving behind the colonists, Martim Afonso continued on with his soldiers to reconnoiter the southern coast of Brazil, particularly the Rio de la Plata. On his return, Martim Afonso distributed the first land grants to the colonists. Later he imported sugarcane and built the first sugar mill. The colony quickly spread from the island onto the narrow shelf of land, covered with a dense tropical forest, between the steep mountains and the Atlantic Ocean.[16]

Martim Afonso envisioned a colony dedicated to the production of sugar, similar to the Portuguese colony of Madeira, and to the extraction of precious minerals, should any be found. Thus, he built São Vicente on the coast so that it would remain closely linked by sea to Portugal. Above the colony, on the Piratininga plateau, lived Tibiriá's tribe of Tupiniquin Indians, known as the Guaianá. They lived in several villages near the present-day city of São Paulo. The Indians preferred the plateau, which had a cooler and drier climate than the coast, and only descended to the sea at certain times of the year to fish and hunt. Hence, as long as the Portuguese remained on the coast and allowed the Indians to fish, the relations between the colonists and the Guaianá progressed smoothly, aided by the intercession of Ramalho. Greatly outnumbered by Indians and isolated from Portugal, the colony was extremely vulnerable to Indian attack. Ramalho persuaded his father-in-law, Tibiriçá, to protect the fledgling Portuguese colony. Indeed, Tibiriçá allowed himself to be baptized, adopting the name Martim Afonso Tibiriçá to emulate the colony's leader, and married several of his daughters to Portuguese men. One of his daughters took the name Beatriz at baptism and married a Portuguese man, Lopo Dias. These were the parents of Suzana Dias.[17] ç The good relations between Portuguese and Indians in São Vicente played a major role in the early success of this colony. Uninterested in the interior and determined to make the sugar economy work, Martim Afonso prohibited his colonists from visiting the plateau without his permission.[18] To Ramalho, he gave the monopoly of supplying the colony with Indian slaves from the plateau.[19]

Very soon after Martim Afonso founded São Vicente, the crown