Preferred Citation: Danielson, Michael N., and Jameson W. Doig New York: The Politics of Urban Regional Development. Berkeley: Published for the Institute of Governmental Studies [by] University of California Press, c1982 1982. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1t1nb1hz/

| New YorkThe Politics of Urban Regional DevelopmentMichael N. Danielson and Jameson W. DoigUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1982 The Regents of the University of California |

To the memory of

Wallace S. Sayre

and

Richard T. Frost

whose insights, enthusiasm and encouragement

shaped the education and future work

of their many students

Preferred Citation: Danielson, Michael N., and Jameson W. Doig New York: The Politics of Urban Regional Development. Berkeley: Published for the Institute of Governmental Studies [by] University of California Press, c1982 1982. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1t1nb1hz/

To the memory of

Wallace S. Sayre

and

Richard T. Frost

whose insights, enthusiasm and encouragement

shaped the education and future work

of their many students

Foreword

This volume is the fourth in the Franklin K. Lane series on the governance of major metropolitan regions. The series is sponsored by the Institute of Governmental Studies and the Institute of International Studies, University of California in Berkeley. Readers of these volumes and other relevant literature will no doubt agree with the authors of this book that similar patterns are found in New York, London, Toronto, Stockholm, and indeed in "every other major metropolitan region in the United States and in other advanced industrial societies." The presence of such common factors and trends, although they assume different configurations in various metropolitan regions, has been demonstrated by the work of many scholars, including Peter Hall, Brian Berry, Marion Clawson, Jean Gottmann, Larry Bourne and William Robson, as well as by the authors of the other Franklin K. Lane books—Donald Foley, Albert Rose and Thomas Anton.

In the present volume Michael Danielson and Jameson Doig have described and analyzed the cultural, economic, political and other social forces shaping development in the New York region. They present a picture of a region singular in its attractions, problems, geographic scope, magnitude of development, and complexity of the network of organizations involved in its governance.

A Major Case Study

The book must be taken seriously as a major study of the nation's largest metropolitan region, and judged at least partly by its success in meeting the specifications and standards of the case study genre. We believe it does so magnificently. Readers are never allowed to forget that they are dealing with a specific region composed of identifiable urban and suburban communities, where individual public and private organizations are interacting to further or forestall specific outcomes. At the same time, the study is comparative in dealing with the many types of actors operating within the New York region.

The volume also offers much more than the standard empirical materials usually found in a case study. Danielson and Doig use the case approach analytically, subjecting the conclusions of other students to the test of congruence with the real world as they see it exemplified in the New York region. One of their major concerns is to reexamine the conclusions reached nearly two decades ago by Robert C. Wood and Raymond Vernon, also based on a landmark study of the New York region. Wood and Vernon contended that "public programs and public policies are of little consequence" in shaping the

metropolis, and that governmental organizations "leave most of the important decisions for regional development to the private marketplace." But our two authors show how developmental decision-making is much more complex. They demonstrate that the Wood-Vernon thesis is inadequate to explain development because it fails to acknowledge the "close interconnection . . . in the United States and in other democratic societies . . . among individual attitudes, governmental policies, and the actions of economic organizations and individuals in the marketplace."

Two Analytical Scales

Danielson and Doig trace the dynamics of this interconnection in their examination of municipal zoning and other local housing, urban renewal and land use policies; of local resistance to regional, state, and federal highway projects; and of the successes and failures of regional agencies in building bridges, tunnels, and airports and in operating rapid transit, buses and commuter railroads. The authors find a variety of relationships which they range along a spectrum from (1) the ratification of decisions made in the marketplace, to (2) a middle position where sensitivity to market forces is tempered with public policy goals, to (3) "the other end of the continuum" where "government actions have a critical initiating role in shaping development."

They have also devised another scale for describing the impact of governmental actions on urban development. Taken together, these two measures are represented in a matrix that can be used in any metropolitan region to identify, describe, and locate governmental units with respect to their degree of dependence on previous actions by economic units, as well as the impacts of the governments' own actions on urban development. The authors have thus supplied analytical tools and concepts that can help to provide an understanding of the role of government in shaping development in other metropolitan regions.

Much More than a Case Study

For still other reasons, this book is much more than a case study of another large metropolis. Admittedly New York's scale and complexity are unique, but its striking features also exemplify important characteristics found elsewhere. Students, citizens and active participants in the governance of other regions can recognize New York as a macrocosm of their own regions: New York resembles other regions, but writ large. The New York region, with the central city and especially Manhattan Island as its major urban core, is certainly "one of the great unnatural wonders of the world," to use Robert C. Wood's phrase, quoted by the authors. Whether New York is accepted as unnatural, natural, or just inevitable, most Americans (and indeed probably most foreigners) love, hate, imitate, fear, embrace or avoid it.

In any event New York continues to be the major urban center of the United States, and indeed of North America. On the other hand New York has not dominated the life of its parent nation like London and Paris, perhaps

because the country is continental in scale, as well as because New York is not the national capital. Moreover, the United States has thirty-four metropolitan planning regions of over a million population, and another forty with populations between 500,000 and 1,000,000. In the complexity of their developmental decisions, all these areas—even relatively new and rapidly growing ones in the Sun Belt—resemble the New York region, on a smaller but nevertheless impressive scale.

With development of automotive transportation and instantaneous communications, the regions of old and newer cities outside the United States are following the development patterns Danielson and Doig have outlined in the New York region. Toronto is an excellent example of a new fast-growing metropolis where, despite governmental reorganizations of major proportions, growth is spilling over the boundaries. Metropolitan Toronto and the Toronto-centered region are essentially a product of the last thirty-five years. During. this time the inner suburbs of the Metropolitan Municipality that was created in 1953 have gone through the typical phase of rapid growth fed by migration from the old central city and elsewhere in Canada, as well as by immigration from abroad. Presently, however, Metro's growth is almost stationary (except for Scarborough), and the fast-growing suburbs are now outside Metro's political boundaries. Metro's inner municipalities are actually losing population.

Meanwhile the inner ring of suburbs has changed socially as well as demographically. According to a recent report of the Social Planning Council of Metropolitan Toronto:

a growing majority of the people who live in the suburbs are tenants, working mothers, new immigrants, elderly struggling against inflation, solitary parents raising children alone, teenagers looking for things to do, unmarried couples living together and the unemployed. It is no longer possible to think of the suburbs as single family neighborhoods surrounding the more cosmopolitan and dangerous inner city. . . . All of Metropolitan Toronto has become a vast urbanized area.[*]

Some Conventional Wisdom Undermined

Another reason why the Danielson and Doig book is not a typical case study is its richness in observations, interpretations, conclusions and generalizations. These should stimulate further intraregional as well as interregional and international comparative research. While any good case study ought to have such by-products, our two authors provide a profusion of intriguing leads and questions for exploration by authors of future volumes in this series, as well as by other students here and abroad.

As noted earlier, their principal purpose is to identify the variety of relationships among public and private actors in the development and redevelopment of the New York region. A centrals recurring theme in their analysis is the importance of governmental organization, decisions and actions. In

[*] * Social Planning Council of Metropolitan Toronto, Metro's Suburbs in Transition, Part II, Policy Report: Planning Agenda for the Eighties (Toronto, Ontario, September 1980), pp. 25–26.

the process of developing this theme, they seriously undermine some conventional wisdom that had seemed to be supported by the Wood-Vernon study of the New York region, noted earlier. Admittedly the interpretation that government serves largely in a secondary role—as contrasted with other prime movers that allegedly determine events—did not originate in the New York studies of Wood, Vernon and their colleagues. Such deterministic theses are, in fact, deeply rooted in the literature of economics. Wood's interpretation in his New York book, 1400 Governments, stood for nearly twenty years without either comprehensive reexamination or a serious head-on challenge. The view of government as ineffective received a major impetus in the postwar era, especially when the big push for urban-metropolitan governmental reorganization of the 1950s and 1960s produced meager results, seeming to prompt the conclusion in some quarters, "oh well, it really doesn't matter anyway." In one form or another, the interpretation that government and public policy are largely incidental—or that government responds to social and economic factors far more than it shapes them—has been repeated by such influential political scientists as York Willbern, Norton Long, and Thomas Dye.

Sorting Out Cause and Effect

Our two authors emphasize how the very complexity of forces shaping an urban region like New York makes it exceedingly difficult "to sort out the most important causes of urban change." Moreover they quote with approval these conclusions of a conference of scholars:

It is always difficult and frequently impossible to isolate cause and effect relationships in any kind of social science research, and policy impact studies pose many particularly difficult, perhaps insoluble, methodological problems.

In fact, this fundamental difficulty in data interpretation has challenged philosophers and scientists at least since the time of David Hume: statistical association does not demonstrate causation. When events are seen to happen together or in familiar sequences, interpretation and inference must be employed in trying to distinguish cause from effect, or cause from incidental phenomena.[*]

Answering the question—"Does governmental policy at the local and metropolitan level make a significant difference?"—calls for such interpretations. We have noted how several writers seemed to doubt that it does. But we also see how Danielson and Doig vigorously—and we believe persuasively—contest the view that government and its activities are only incidental.

[*] * The social sciences must constantly infer cause-and-effect relationships to help interpret data. In fact, to get beyond data collection and description of observations—which can be highly useful in their own right—the researcher must try to identify probable cause-and-effect relationships. Nearly always this means making assumptions that go beyond the evidence at hand: "only under very limited conditions can one unequivocally determine the underlying causal structure among the factors from the correlations among the observed variables. This fundamental indeterminancy . . . is due to the indeterminancy inherent in making inferences about the causal structure . . . [emphasis in original]. Jae-On Kim and Charles W. Mueller, Introduction to Factor Analysis: What It Is and How to Do It (Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1978), p. 8.

The Value-Laden Consequences of Structure

In fact, they convincingly argue that the very framework and structure of government can have important influences on the way governments make decisions and implement them, as well as on the substance of the decisions. Pointing out that organization and leadership in the New York region are more fragmented than in any of the nation's other regions, they go on to emphasize how such a structure can have value-laden consequences:

Fragmentation makes it difficult for major officials in the region to analyze trade-offs, e.g., between environmental costs and job-creation benefits, and when the cost-benefit ratio is favorable, to press ahead vigorously with needed projects. Consequently . . . fragmentation tends to aid those who counsel delay and inaction in the use of government power to advance developmental projects.

At the beginning of the book, the authors had already emphasized how fragmented government helps determine the structure of politics, programs and interrelationships:

The fragmented character of the governmental system both permits and encourages the region's citizenry to focus their attention on narrow and immediate problems. Businessmen, homeowners, parents, motorists and others concerned with particular policies-and programs organize along the lines of the governments' geographic and functional divisions. . . . [B]oth public and private participants in the region's political system generally react to issues in terms of a territorial or functional frame of reference. . . .

Long Time Spans for Policy Implementation

In attempting to interpret how governmental action can influence events we must recognize that—even without structural impediments like fragmentation—long time spans often elapse before the potentials of policies and program innovations can be fully realized. These long intervals no doubt contribute to the oft-expressed opinion that governmental actions do not produce the results intended, or are highly disappointing in their outcomes. But such criticisms tend to ignore or minimize the exceedingly important temporal factor in governmental efforts that are intended to effect significant social or economic change. Thus it usually takes a lot of time to achieve major innovations in governmental policy, still more time to put the innovations into effect, and yet more time to see substantial results, even when the policies are pursued with persistence and continuity.

Given this temporal factor, attempts to evaluate governmental policy impacts over comparatively short-run periods can sometimes grossly underestimate the role of governmental policies and programs. An example is the effort to evaluate the impact of San Francisco's three-county rapid transit system, BART. The crucial bond referendum that put BART into being was held in November 1962, and the system was largely built in the 1960s. Natur-

ally eager to learn from the unique BART experience, the federal authorities sponsored BART-impact studies in the 1970s, when the system had been in operation only a few years. Impacts were found to be mostly minor, except of course for the obvious one of lots of people riding at the rush hour. But other major impacts, e.g., on land values, land uses, population densities and distribution, locations of employment, and journey-to-work patterns are likely to take decades to work themselves out, rather than a few short years. In fact, the 1990s may be a far better time than the 1970s to do meaningful impact studies of BART.

Unfortunately, policy research is often expected to evaluate the effectiveness of new initiatives on the basis of experience in much shorter time spans. It thus has to judge processes that are far from complete. This is likely to defeat the purpose of the experiments, especially if they are terminated or curtailed without a fair test of the results. It also underestimates the role and effectiveness of government, thus seeming to support one of the theses that Danielson and Doig challenge.

A Look to the Future: No Drastic Consolidation

Danielson and Doig do not attempt to predict in detail future development in the New York region. Nor do they prescribe a specific restructuring of relationships among the many governmental actors. In fact, they foresee a continuation of the past and recent trends into the future:

the variables that underlie the past behavior of the region's public officials will also be central to understanding their activities, their failures, and their successes in the next several decades. And we expect that the same themes and patterns underlie the political economies of other metropolitan regions.

In short, the modern metropolis is an "ecology of organizations"—public, private, and mixed. Each pursues its own interests, but with constant infringement from other organizations having different goals. These relationships are highly varied and complex, but are neither wholly random nor only reactive. Costs and benefits can be calculated, externalities can be identified and assessed, incremental adjustments can be made, and occasionally the system of relationships can be significantly rearranged.

The authors have carefully identified and developed typologies of interrelationships among governmental organizations. These include organizations of limited scope, as well as more extensive geographic extent. They include organizations with single or limited purposes that are highly focused functionally and with substantial ability to concentrate resources in achieving their goals, as well as multiple-purpose governments having varied and often conflicting constituencies that may be constantly battling for shares of scarce resources.

Both limited-purpose and multiple-purpose agencies that are geographically small (e.g., small special districts and authorities, and small municipalities) are seriously limited in their ability to command and focus

resources in achieving their goals, particularly when these require some kind of regional consensus and/or action. Even the large-scope multiple-purpose agencies that deal with extensive geographic areas (e.g., state and federal governments) have been successful with regional activities only when the state or federal agency involved is able to operate in relative isolation from the rest of the government—in other words, to act as if it were a special-purpose government. In short, the authors suggest that only regional special-purpose agencies will be able to surmount the divisive pursuit of constituency interests, and the consequent scattering of resources that is inherent in the current governmental fragmentation:

In view of these constituency problems, which confront the national and state governments and most general-purpose governments in every region, there may of course be substantial advantages in looking. . . . [Thus] perhaps we need to create or find an engine of governmental power that can assemble the resources and overcome the difficulties, somewhat insulated from the buzzing confusion of constituent demands . . . [and perhaps] we need to apply to current and future efforts the advantages that the Port Authority brought to the George Washington Bridge project in the 1920s, and to the marine terminals in the postwar era, and which the carefully crafted alliances of the [Newark Housing Authority] brought to Newark's redevelopment in the 1950s. Indeed, this is the perspective that underlies the Port Authority's current initiatives in the region.

It is virtually certain that no drastic consolidation will integrate local governments and special-purpose agencies into a single regional government in the New York region. Even if the 1898 creation of Greater New York City—consolidating New York, Brooklyn, two other cities and all or parts of 21 towns—were repeated on a much grander scale, the region's governance would not be "consolidated across state boundaries." And even with a comprehensive metropolitan government, the governance of a large region like New York's would still comprise varied networks of intergovernmental, interagency and intergroup relationships involving units within and without the region. These of course include the national and state governments—themselves fragmented structurally and programatically—which also participate actively in the governance of metropolitan regions.

Given these complexities, the search continues for feasible, workable ways of structuring power and governmental relationships for greater effectiveness in achieving consensus and marshalling resources for regional endeavors. We can hope and anticipate that our two authors as well as other researchers will follow the unfolding story of this fascinating, frustrating and troubled, but also preeminently influential metropolis.

STANLEY SCOTT

EDITOR, LANE FUND

PUBLICATIONS

VICTOR JONES

COEDITOR, LANE STUDIES IN

REGIONAL GOVERNMENT

BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA

JANUARY 1981

Acknowledgments

We have incurred many debts during the years in which this study was conceived, nurtured, and completed. Our interest in metropolitan politics was originally stimulated by the two teachers and friends to whom this volume is dedicated, Richard T. Frost of Princeton University and Wallace S. Sayre of Columbia University. We have also learned much from Marver H. Bernstein, W. Duane Lockard, and the late John F. Sly, teachers and colleagues at Princeton. And a special note of thanks is due Robert C. Wood, who both encouraged our work and shaped the way a generation of political scientists have thought about the role of government in urban development.

Victor Jones and Stanley Scott of the Institute of Governmental Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, initially suggested that we undertake a study of the New York region as part of the Lane Studies in Regional Government. Over the years, they have been tolerant of our delays in completing the study, encouraging as to our approach, and lively commentators on the manuscript.

Others who read the manuscript in whole or in part, and offered helpful comments, include: Roger Gilman, Peter Goldmark, Harvey Sherman, John Brunner, and Robert Foote of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey; William Shore and his associates at the Regional Plan Association of New York; John Harrigan of Hamline University; Stephen David of Fordham University; Charles Adrian at the University of California, Riverside; Erwin Bard, now retired from Brooklyn College; Annmarie Walsh of the Institute of Public Administration; Robert Curvin of the New York Times; Douglas Arnold, David Billington, and David Hammack at Princeton University; Chris Forbes of the Westway Coalition; Joan Aron and Mitchell Moss of New York University; Ellen Comisso at the University of California, San Diego; Jack Nagel at the University of Pennsylvania; and Charles Anderson of the U.S. Department of Transportation.

In addition, insights on particular development issues were offered by Arthur Gordon of the New York State Comptroller's Office; Jack Krauskopf, now in the New York City government; Chester Mattson of the Hackensack Meadowlands Development Commission; and Robert Moses.

Many former students gathered materials, wrote papers, and added to our understanding of pieces of the puzzle. These included William Bohnett, Andrés Gil, Lawrence Goldman, Duncan Grant, Sanford Greenberg, Norman Jacknis, Arthur Kent, David Kessler, Kate Levan, Melvin Masuda, Martin Murphy, Glenn Sharer, Lawrence Serra, and Joseph Taylor. And the graduate students in the Woodrow Wilson School's policy workshop on development issues in the New York region at Princeton University during the spring of

1980 helped sharpen our thinking on a number of issues.

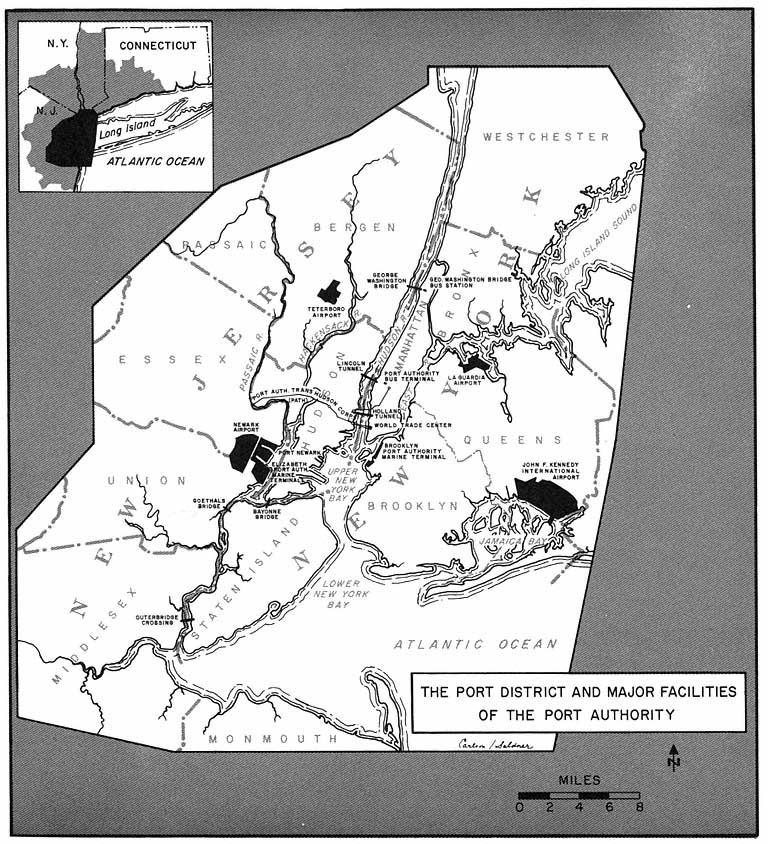

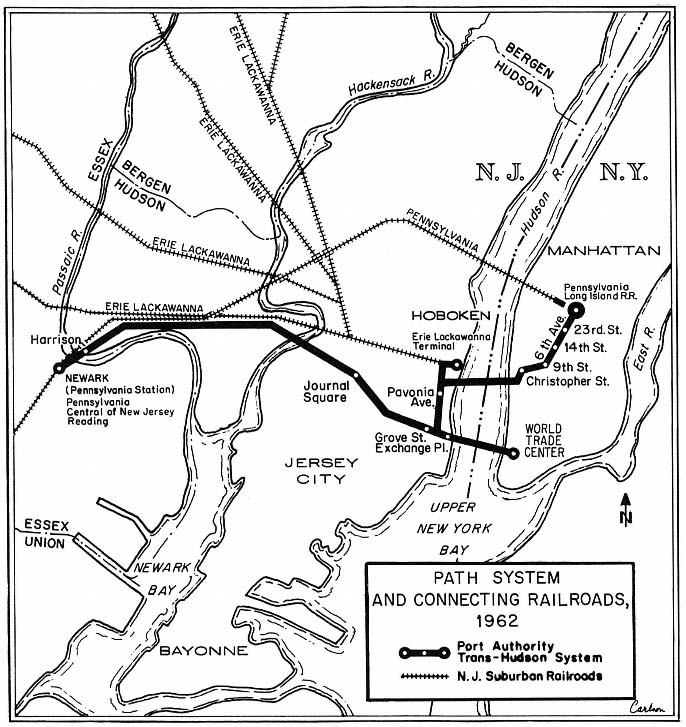

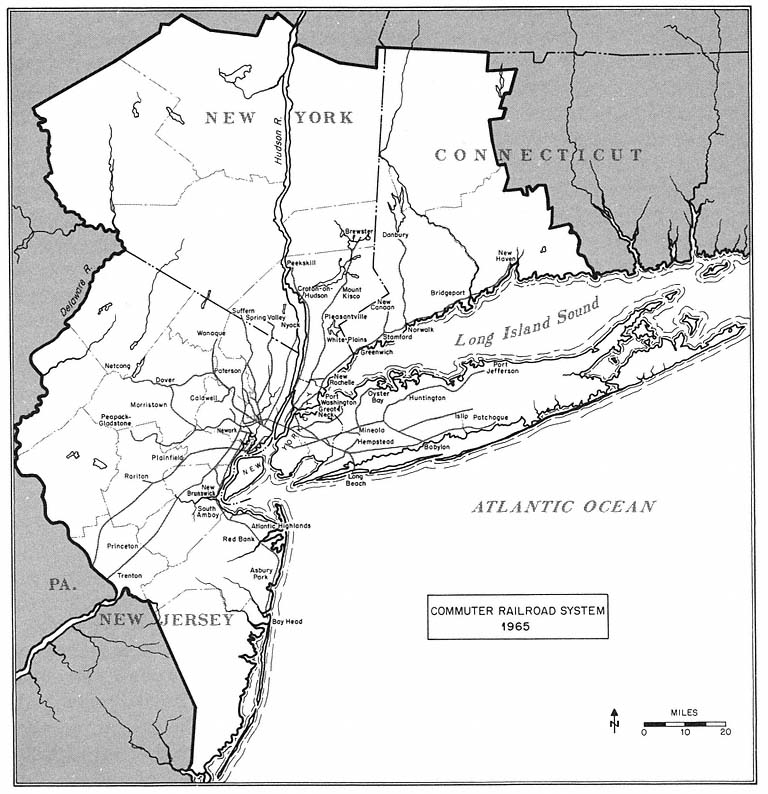

We received assistance from numerous helpful people in identifying and locating photographs, correspondence, and other fugitive materials for the volume, including: Marion Ritz at the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority; Louis Schlivek of the Regional Plan Association; Thomas Young and Steven Weissmann at the Port Authority; Barbara Reilly, NJ TRANSIT; Andrew Beresky at the College of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey; Wendy Shadwell and Helena Zinkham at the New York Historical Society; Susan Anisfield of the Hackensack Meadowlands Development Commission; and officials at the New Jersey Housing Finance Agency. To Charlotte Carlson and Elaine Seldner, we owe a special word of thanks for reproducing and constructing a fine set of maps.

The manuscript was typed and retyped through the collective efforts of Peg Anabel, Lucille Crooks, Betty Drotar, Jerri Kavanagh, Barbara Keller, Mary Leksa, Jean Nase, Nan Nash, Mary Robertson, and especially June DeRose, who combined organizing, typing, and research skills to keep our manuscript together and to locate the sources we needed in the final two years.

Generous research support from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs Princeton played an important part in providing us with the means to undertake this study. We appreciate the personal interest and institutional backing provided by Marver H. Bernstein, John P. Lewis, and Donald E. Stokes.

We are also grateful to the Lavanburg Foundation, whose officers, led by Oscar S. Straus and Ruth M. Glover, provided funds to underwrite the production of maps and photographs, and to assist in other elements of publishing and distributing this volume.

Books in process often disrupt the lives of those who live with authors, and this study has been around two households for more than a decade. Our children, who have grown much faster than the New York region during the years we worked on the book, were by and large tolerant. Our wives, Patricia R. F. Danielson and Joan N. Doig, helped us carry through to the finish, and with Jessica Danielson assisted in proofreading the volume.

As is always the case, many were helpful, but what follows is our responsibility.

MICHAEL N. DANIELSON

JAMESON W. DOIG

PRINCETON, N. J.

MAY, 1981

Abbreviations

|

Terms of Office

Selected Political Executives in the New York Region, 1954–1981

|

1—

Government and Urban Development

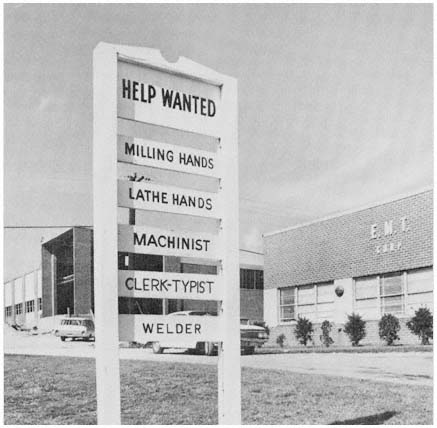

Cities grow and deteriorate, highways and houses spread across the urban landscape, racial and ethnic minorities cluster in ghettos, sources of water supply are polluted and reclaimed. These and other features of urban development are found in every major metropolitan region in the United States. And the basic elements differ little in other advanced industrial societies.[1] The patterns of development that characterize the modern metropolis are the product of the complex and continuing interactions of geographic, technological, economic, political, and other social factors which constantly mold and alter urban society.

Our central concern in this study is with the role of government in shaping urban development in modernized societies. More specifically: To what extent do the actions of governmental organizations have a significant independent influence on urban development, rather than having no significant role, or affecting development only by ratifying and supporting decisions previously made in other subsystems of the society, such as the private marketplace? By governmental organizations, we mean those organizations which authoritatively allocate values (i.e., make binding rules) for a society, and which are primarily oriented toward this function, together with subordinate units of such organizations.[2] The actions of governmental organizations must be examined in the context of the broader pattern of human relationships concerned with the authoritative allocation of values, i.e., the political system.[3]

The New York region is the focus of our study. Our immediate concern is the analysis of the role of government in shaping development within this metropolis, the largest and most complex in the United States. We also seek broader relevance. The approach used in this study should be helpful in understanding urban development in other areas; and our conclusions concerning the impact of city and suburban governments, public authorities, state and federal agencies, and other governmental units will suggest generalizations that apply in other regions, especially in the United States.

[1] See, for example, Peter Hall, The World Cities, second edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977).

[2] Organizations that are not primarily oriented toward the rule-making function, such as the family or the church, may also make binding rules for a society; and in relatively nonmodernized societies this is frequently the case.

[3] See Robert A. Dahl, Modern Political Analysis, third edition (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1976), p. 3 ff.; Marion J. Levy, Jr., Modernization and the Structure of Societies: A Setting for International Affairs (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1966), especially pp. 290–293, 333–336, 436 ff.

The difficulty in assessing the influence on urban development of any one set of organizations should be emphasized at the outset. There is, as York Willbern points out, a "chicken-and-egg" character to the question.[4] The many governmental and nongovernmental organizations operating in the metropolis influence each other continuously, making it very difficult to sort out the impact on development of any one factor. Moreover, the problem of determining cause and effect is particularly complex when one is analyzing causal factors related not to a clearly measurable outcome (such as the number of automobile accidents), but to a much broader set of outcomes comprising "urban development."

These difficulties have not prevented social scientists from assessing the impact of governmental organizations and other institutions on urban development. The most intensive analysis of this issue, certainly in terms of the New York region and perhaps for any modernized urban complex, was that conducted in the late 1950s by Raymond Vernon, Robert C. Wood, and their colleagues in the New York Metropolitan Region Study. Their conclusion is, to quote Wood, that "public programs and public policies are of little consequence" in shaping the metropolis. Governmental organizations "leave most of the important decisions for Regional development to the private marketplace."[5] Other observers such as York Willbern and Scott Greer have generally reached the same conclusion with regard to urban development in the United States.[6]

Our own position differs from that of Wood and Vernon and others who emphasize the dominance of economic factors. Admittedly, in some situations, governmental action appears to do little more than ratify decisions made in the private marketplace. On the basis of our review of the Wood and Vernon studies, however, together with additional evidence presented in the following chapters, we argue that governmental influence is frequently impor-

[4] York Willbern, The Withering Away of the City (University, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 1964), p. 30. Cf. Robert A. Dahl, Democracy in the United States, second edition (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1972), Chapter 21. On the general problem of analyzing causation in human affairs, see Robert Maclver, Social Causation (New York: Harper & Row, 1964).

[5] Robert C. Wood, with Vladimir V. Almendinger, 1400 Governments: The Political Economy of the New York Region (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961), pp. 173, 175; see also pp. 2–28, 110–113, 169–175, 190–199. Vernon's conclusions are set forth in the summary volume of the Metropolitan Region Study, Metropolis 1985 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960), especially chapters 10 and 11; see also Raymond Vernon, The Myth and Reality of Our Urban Problems (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1966).

[6] See York Willbern, The Withering Away of the City, especially pp. 29–32; Edward C. Banfield and James Q. Wilson, City Politics (New York: Vintage, 1963), p. 344; Scott Greet, Urban Renewal and American Cities (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1965), p. 164; Norton E. Long, The Polity (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1962), pp. 162–164; Martin Meyerson, "Five Functions for Planning," in Edward C. Banfield, ed., Urban Government, second edition (New York: Free Press, 1969), p. 589 (an article first published in 1956); Edward C. Banfield, The Unheavenly City Revisited (Boston: Little, Brown, 1974), chapter 2. Most of these authors rely heavily on the evidence and analysis provided in the volumes by Wood and Vernon. Conflicting conclusions, suggesting a more important role for government in urban development, are found in Benjamin Chinitz, "New York: A Metropolitan Region," in Cities: A Scientific American Book (New York: Knopf, 1965), pp. 113–121; Jameson W. Doig and Michael N. Danielson, "Politics and Urban Development," International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 7 (March 1966), pp. 76–95; and Michael N. Danielson, The Politics of Exclusion (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976).

tant. In many cases, public programs significantly modify or amplify developmental trends, and in some instances, governmental actions have a critical initiating role in shaping urban development. These variations in governmental influence can be understood in terms of several factors—areal scope, functional scope, and the ability to concentrate resources. In this study, we define these factors, and then use them to analyze the influence of various types of governmental units.

Before examining the complex issue of cause and effect raised by the question of what influence—if any—does government have on urban growth and change, it is necessary to define what we mean by "urban development." Some studies refer to "urban development" as the process of change in urban areas; other discussions use the term to denote the outcome of the process at any point in time. The latter definition is used in this volume. More specifically, our analysis focuses on the distribution of residences in urban regions, in general and by income level and race; on the distribution of jobs; and on the location of major transportation facilities. This focus is similar to that used in the Vernon studies, although that analysis gave primary emphasis to the distribution of jobs and residences.[7]

In our study, as in Vernon's, the main emphasis is on "physical" aspects of urban society. The quality of education, police behavior, the welfare system, health care, and other service areas are not directly under scrutiny. It may be that many of the forces—governmental and otherwise—which are considered in our study also shape these aspects of urban life, but we leave that exploration for another study.

We begin our analysis of the influence of government on urban development in the New York region by briefly examining the governmental system. The remainder of the chapter explores in detail the general problem of evaluating governmental influence on urban development. This analysis provides the framework which is used in the chapters that follow.

Governments in the New York Region

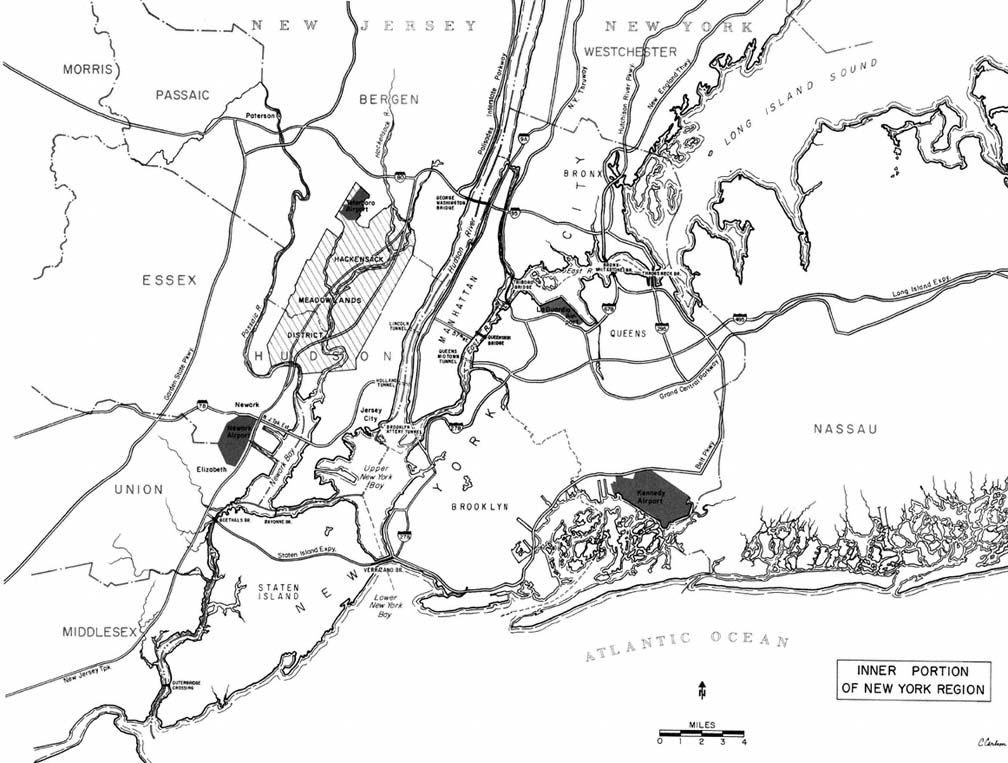

As Robert Wood has commented, the tristate region centering on New York City contains "one of the great unnatural wonders of the world"—an interrelationship of governments "perhaps more complicated than any other that mankind has yet contrived or allowed to happen."[8] The governments of three states and the nation share responsibility in the metropolis with more than two dozen county political units, over 700 municipalities, and several

[7] See Edgar M. Hoover and Raymond Vernon, Anatomy of a Metropolis: The Changing Distribution of People and Jobs within the New York Metropolitan Region (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1959), p. 1; Vernon, Metropolis 1985, p. 215, and chapters 1 and 11; Wood, 1400 Governments, pp. vii, 169. At times, Wood gives transportation factors coequal status: "In particular, we focus on the process for making those [governmental] decisions which most strongly affect the private sector, that is, affect the location of firms and households or the transportation of goods and people." Wood, 1400 Governments, p. 3.

[8] Wood, 1400 Governments, p. 1.

hundred specialized functional districts.[9] The number of governmental units in the New York region in 1977 is shown in Table 1.

| ||||||||||||||||||

Of nearly 2,200 nonnational units of government in the New York region, the three states possess the broadest array of powers. Each state has a wide range of policies that affect its portion of the metropolis, and all local government activity is subject to ultimate state control. But since New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut share these responsibilities, state policy in the New York region is far from uniform. Each state has distinct traditions of local government, and different policies for transportation, education, welfare, recreation, state aid to local governments, and other matters that affect the metropolis. These policies and programs are shaped not only by the needs and demands of residents of the New York region, but also in response to a variety of other urban and rural pressures in each state. Another important characteristic of state action is the fragmentation of programs among functional agencies within each state, many of which, such as highways and education, have considerable autonomy from the governor and legislature.

As in most metropolitan areas, local governments in the New York region vary greatly in size, governmental structure, policy goals, tax resources and expenditures, and political styles. One of these local governments, New York City, encompasses almost half of the region's population. Like the state governments, the complex governmental system of New York City is characterized by internal fragmentation and functional autonomy. In addition to New York, the region includes several large cities—Newark, with 329,000 residents in 1980, and Jersey City with 224,000, together with Paterson (138,000) and Elizabeth (106,000). Jersey City is itself the largest center in a

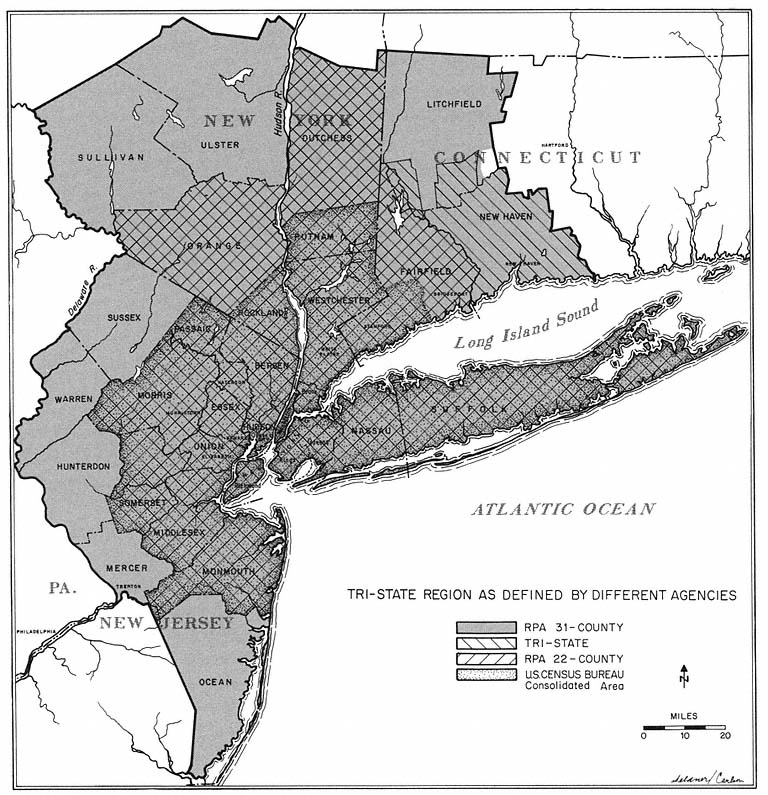

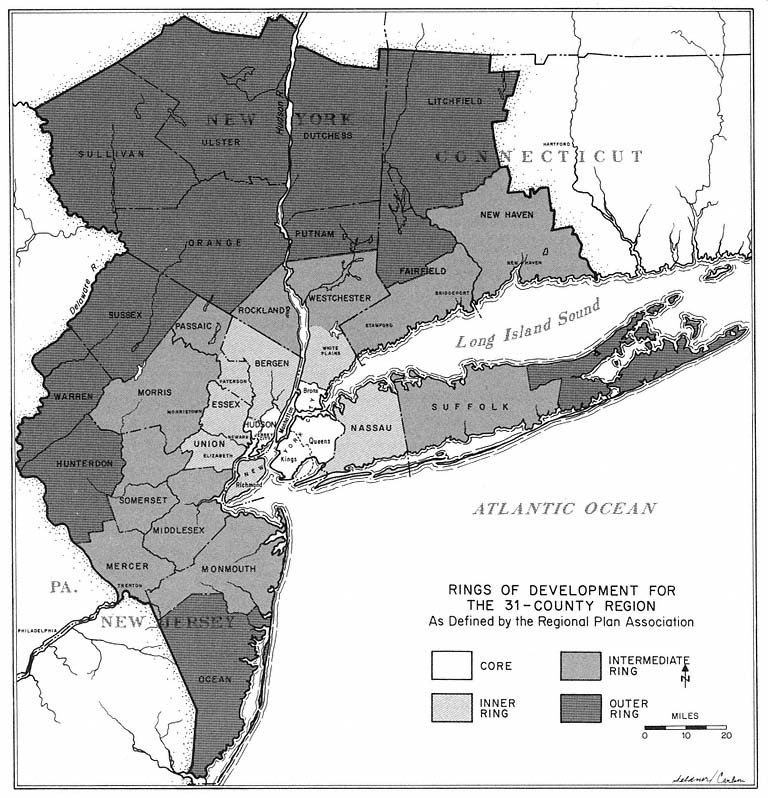

[9] The numbers of governmental units vary, depending on whether the 22-, 25-, or 31-county definition of the region is used. (See Chapter Two for a discussion of the definition of the region.) In contrast with the other two states, the Connecticut counties no longer have any governmental powers.

cluster of older cities comprising Hudson County, with a total population of 557,000.[10]

The region also includes more than a dozen other cities with populations of over 50,000, many of which would be metropolitan centers if located outside the New York region. Interwoven with this complex of cities are suburban counties and municipalities, ranging from the placid local governments in the affluent enclaves of Westchester and Morris counties to the more intensively settled and financially hard-pressed suburbs of Middlesex and Nassau counties.

Finally, layered over this mosaic of governments are the special units, most of which have relatively narrow functional responsibilities. Most common are the school districts, which spend up to 75 percent of the local tax dollar in the region's newer residential suburbs. Most powerful are the regional public works enterprises, particularly the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, with assets of over $3.6 billion in tunnels, bridges, airports, port facilities, a rail transit line, bus and truck terminals, and a world trade center. Until recently, great influence also was wielded by the cluster of specialized agencies long controlled by Robert Moses, a public entrepreneur without peer in urban America, whose monuments include bridges, tunnels, parks, parkways, garages, housing projects, and a coliseum. Two new regional organizations were added in the 1960s—the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which now controls the Long Island Rail Road, the subways and toll bridges of New York City, and other transport facilities; and the Urban Development Corporation, created by New York State in 1968 to build housing and other projects without the encumbrance and inconvenience of local zoning and building restrictions.[11] Beyond the school districts and the regional authorities are several hundred other special districts concerned with such problems as water supply, sewage disposal, parking, and housing, and with jurisdictions ranging from several counties down to individual municipalities.

The impact of these governments on citizens varies greatly, depending on where they work and live. Tax burdens differ from state to state, from city to city, and from suburb to suburb. The per pupil expenditure for education, the amount and nature of public housing and downtown renewal, and other public services vary widely. Integrated regional policies for these and most other matters of public concern do not exist in the New York area.

These variations in effective demand and public policy in different parts of the region are readily illustrated by expenditures on education and on welfare-related services.[12] Some comparative data for New York City and suburban counties in the New York portion of the region are summarized in Table 2. These figures illustrate the relatively heavy per capita outlays for welfare and related services in the region's largest older city, compared with suburban areas.

[10] Hudson County includes Bayonne (65,000), Union City (56,000), Hoboken (42,000), and several smaller municipalities. All population figures are for 1980.

[11] The Urban Development Corporation's authority to override suburban zoning and building codes was severely restricted by the New York legislature in 1973; see Chapter Five.

[12] For detailed analyses of local expenditures in the New York region, see Wood, 1400 Governments, Chapters 2–3 and Appendix A; Regional Plan Association, Public Services in Older Cities, May 1968; and recent RPA and Tri-State Regional Planning Commission reports.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The wide variations among municipalities can also be indicated by comparing annual school expenditures per pupil within the New York region. At the upper end of the range are wealthier suburbs, while a number of older cities are concentrated toward the lower end of the scale. Table 3 gives a sample of the figures for the New Jersey portion of the region. Similar disparities are found in taxable valuation ("ratables") and tax burdens in the region. In the affluent suburb of Millburn, for example, ratables average $18,760 per resident, and the effective local tax rate (per $100 of actual value) is only $3.50. But in Elizabeth, only $8,495 in ratables stand behind each resident and the tax rate is $4.36; while in Jersey City, the ratables figure drops to $3,003 per capita, and the tax rate climbs to more than $7.50.[13]

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The fragmented character of the governmental system both permits and encourages the region's citizenry to focus their attention on narrow and immediate problems. Businessmen, homeowners, parents, motorists, and others concerned with particular policies and programs organize along the lines of governments' areal and functional divisions. In New York, as in other urban areas, both public and private participants in the region's political system generally react to issues in terms of a territorial or functional frame of reference. Consequently, as will become apparent in later chapters, municipal zoning policies and state highway plans are usually determined on the basis of a narrow calculation of costs and benefits. Affecting these calculations, in addition to financial considerations, are psychological factors, such as subur-

[13] All ratables and tax rate figures are for 1976; see New Jersey Division of Local Government Service, Annual Report, 1976 (Trenton, N.J.: 1976).

ban antagonism toward the older cities, racial and ethnic fears, and hostilities between those who would spend more for highways and those who would improve mass transportation.

Despite the localist and particularist bias of the region's political system, many problems cannot be dealt with adequately by individual local governments. As a result, networks of horizontal agreements have developed responding to such problems as traffic control, water supply, and refuse disposal. Such limited joint efforts are likely to develop "only when specific problems become acute and when the financial costs to be borne by each government can be clearly related to local benefits."[14] When benefits and costs cannot be readily identified and assigned—as in air pollution control and mass transportation—horizontal cooperation at the local level is unlikely to develop in the New York region.

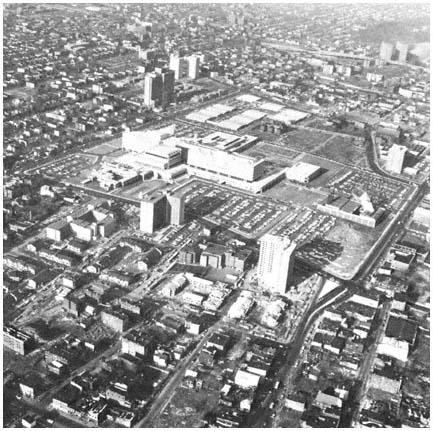

In addition, a few program areas in the region have been characterized by a high degree of vertical functional cooperation. In highway construction and urban renewal, in particular, federal financing encouraged close relations among specialists at all three levels of the federal system. One example of vertical functional integration is the urban renewal programs of Newark and New York City, as they developed during the 1950s and early 1960s. Another is the regional highway program, where a complex alliance evolved over four decades, involving federal and state highway agencies, the Port Authority, the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, state toll road agencies, and most recently the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.[15]

As these functional alliances suggest, state and federal activities are important elements in the region's political system. During the postwar period, the dominant thrust of these activities has been to support and reinforce the areal and functional fragmentation of the region's political system. Financial assistance, particularly from the states to meet educational needs, has helped maintain the viability of the small-scale suburban municipalities and school districts. Most state and federal aid programs have been functionally specific, tending to weaken the integrative capabilities of general government. Where governmental action requires interstate cooperation, as in water and air pollution, conservation, recreation, and mass transportation, differing perspectives and priorities have made it difficult for state leaders to collaborate effectively. These characteristics of state and federal involvement in the region's political system reflect the localist and particularist perspectives that legislators elected from various parts of the New York region bring to the state capitals and to Washington.[16]

Since the early 1960s, increased efforts have been made, particularly by the federal government, to overcome this fragmentation. At the national level,

[14] Jameson W. Doig, Metropolitan Transportation Politics and the New York Region (New York: Columbia University Press, 1966), p. 237.

[15] See Harold Kaplan, Urban Renewal Politics: Slum Clearance in Newark (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963); Doig, Metropolitan Transportation Politics, Chapters 2 and 10; Wood, 1400 Governments, Chapter 4.

[16] See Michael N. Danielson, Federal-Metropolitan Politics and the Commuter Crisis (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965), Chapters 7 and 10; Harold Herman, New York State and the Metropolitan Problem (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1965), Chapters 7–8; Doig, Metropolitan Transportation Politics, Chapters 5, 8–10.

formal requirements for interagency consultation have increased. For example, officials in the Department of Transportation and the Department of Housing and Urban Development must coordinate the development of transport plans in metropolitan areas; and a host of federal agencies were supposed to cooperate in planning, funding and implementing projects in Model Cities neighborhoods in the older cities. At the regional level, Washington has sought to foster the coordination of local, state, and federal planning across jurisdictional and functional lines by making federal aid in a number of program areas conditional on the existence of an areawide planning process. In the New York region, these responsibilities have been assumed by the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission, composed of federal, state, and local officials. To date, as indicated in later chapters, these efforts have had little significant impact on the traditionally separate funding and implementation of highway, housing, and other functional programs in the New York region.

The Impact of Government on Development

In view of the profusion of governmental units pursuing different and often conflicting policies, and the clear influence of economic forces within every metropolis, the presumption readily emerges that government has little or no impact on urban development. In this section, we consider the approaches of Robert Wood and Raymond Vernon, whose pioneering analyses and conclusions emphasize this position. We then outline a contrasting approach, suggesting a far more significant governmental role in urban development.

Government as Inconsequential: A Critique

In 1400 Governments, Wood divides the governmental institutions of the New York region into two categories: agencies with "more or less Regional responsibilities"; and local governments together with "their satellites, the small special-purpose districts." In the first category, Wood concentrates on federal, state, and regional agencies concerned with transportation, water supply, and housing and urban renewal. These agencies "ride with" and "abet the economic forces already at work," rather than initiating new patterns of population settlement and economic growth. This occurs, Wood argues, because "conditions of institutional survival" make it difficult for these organizations to do otherwise. In seeking to maintain their economic and political power, the agencies favor private over public transportation, and support urban renewal in the central business district and suburban home construction, rather than improved housing in the ghettos. As a result, these regional agencies "support the present lines of development. They underwrite and accelerate the process of scatteration."

Local governments "arrive at their positions of negative influence" by a different route. Each community seeks to upgrade its own services and general environment locally, while maintaining its independence of action. However, because there are many units, each using land-use controls, building regulations, and other policies in trying to maximize local interests, the local

governments "tend to cancel one another out." According to Wood, business-men and households are given a number of options from which to choose, and the pattern of development is determined mainly by their preferences, not by government policies.

The net result, in Wood's view, is that governmental activities are of "little consequence" in urban development. "Most of the important decisions" are left "to the private marketplace."[17] As noted earlier, this argument has been widely accepted by students of urban affairs as applicable not only to the New York region but also to urban America generally.

Wood's approach, however, oversimplifies the developmental process in two ways. First, his emphasis on a single generalization obscures the wide variations in governmental influence found in New York and other metropolitan regions. Consequently, he fails to explore the conditions under which governmental units are likely to play either greater or less important roles. Wood himself was aware of these variations, and the detailed materials in 1400 Governments describe several exceptions to the generalization. Yet his concluding chapter emphasizes the major theme, and this thesis has predominated in the writings of Vernon, York Willbern, and others who have relied upon Wood's research.[18]

The other difficulty in Wood's approach is his failure to give close consideration to individual and group preferences that underlie the actions of private economic and government units—preferences which result in a close intertwining of economic and political forces. In the New York region, as in any democratic political arena, governmental action is strongly influenced by the general values held by the voter, especially those values promoted by organized interest groups and public officials.[19] Underlying the region's economic system—which comprises the activities of producers, distributors, and consuming units operating in the marketplace—are general goals or values held by the ultimate consumer. Since the voter and consumer are largely the same, government and private economic organizations tend to respond to the preferences of the voter-consumer. To argue, then, that public policies "abet

[17] Wood, 1400 Governments, pp. 172–175; see also pp. 2–28, 110–113, 169–172, 190–199. Vernon's conclusions, which are similar, are set forth in Metropolis 1985 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960), especially Chapters 10 and 11. As noted above, the analysis and conclusions in these two books are focused primarily on forces influencing the distribution of jobs and residences in the region.

[18] To those familiar with the later work of Robert Wood and with his career in the public sector as a high official of the Department of Housing and Urban Development. president of the University of Massachusetts, and superintendent of schools in Boston, it is clear that Wood's views concerning the role of government in urban development have evolved since he wrote 1400 Governments . His public efforts and later writings, such as The Necessary Majority (New York: Columbia University Press, 1972), indicate a strong commitment to using governmental power to alter urban development—through such efforts as the model cities program and the creation of a major campus of the University of Massachusetts in Boston. Nonetheless, Wood's analysis in 1400 Governments must be given serious attention. It resulted from a comprehensive scholarly examination of the central question of this study—the role of government in influencing urban development. And Wood's conclusions, combined with those of his colleague Vernon in Metropolis 1985, have been highly influential in the literature, as indicated above in note six.

[19] Following Dahl, a democracy is defined as "a political system in which the opportunity to participate in decisions is widely shared among all adult citizens." Robert A. Dahl, Modern Political Analysis, third edition (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1976), p. 5.

the economic forces already at work" is to misinterpret the relationships. Generally, activities in both areas respond to the dominant configuration of underlying social values.[20]

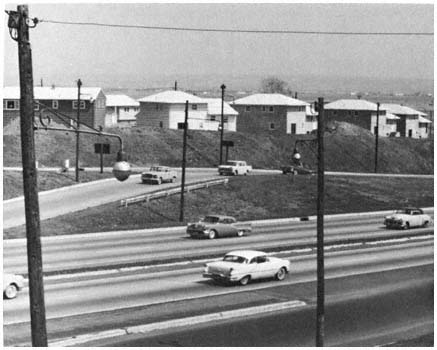

These relationships can be illustrated by an aspect of urban development that is of particular concern to Wood and Vernon—the process of suburban growth or "scatteration." Privacy and open space are significant goals for a large proportion of Americans.[21] Increases in per capita wealth and advances in technology have made feasible widespread ownership of automobiles and single-family homes; and autos and houses both support the goals of privacy and open space. Therefore, in their role as consumers, Americans have bid for automobiles and houses—the latter largely in suburbia because of land availability and cost, as well as to achieve privacy—and these goods have been produced. Meanwhile, in their political role, Americans have provided support for federal mortgage programs and vast federal-state highway programs that make more feasible both home ownership and automobile access to suburban homes and jobs.

This process is complicated, of course, by a variety of feedback mechanisms and efforts of economic and political organizations to advance their own interests. For instance, while the quest for space and privacy is a fundamental goal, the desire to maximize these values has been further stimulated by the production of automobiles, highways, and suburban homes, together with the advertising campaigns and political activities of groups that benefit directly from the sale of suburban land, the construction of homes, the manufacture of automobiles, and the building of roads. These feedback mechanisms and institutional considerations illustrate the close interrelationships among political, economic, and other aspects of human behavior; they do not support the notion that private economic units have a prior or more basic role.[22]

[20] The voter and consumer are not identical for several reasons. For example, the proportion of the poor who vote and are politically active is much less than that of the middle and upper classes; this relative political inactivity tends to reduce the impact of the poor on government policy. At the same time, of course, poverty reduces their influence as consumers. The impact of the voter also is shaped by the historical structure of government—e.g., in the United States, the allocation of seats in the United States Senate without regard to population, and the ability of small groups of voters to create insulated municipal enclaves, which tend to be responsive only to the narrow interests of their relatively homogeneous suburban populations.

[21] Evidence on the importance of privacy and open space as social values in the United States is provided in John B. Lansing, "Residential Location and Urban Mobility: The Second Wave of Interviews," Survey Research Center, University of Michigan, 1966, and other SRC reports. The reports are also considered in William Michelson, "Most People Don't Want What Architects Want," Trans-action 5 (July/August 1968), pp. 37–44. Cf. Vernon, Metropolis 1985, Chapter 9. Privacy and open space are highly desired by most members of other industrialized societies as well; see Hall, The World Cities .

[22] The use of "economic," "political" and "governmental" warrants a note of clarification, particularly since "economic" and "political" are terms that may refer either to concrete organizations or analytical categories. This study focuses on concrete organizations, called governmental units and private economic units (mainly private corporations and households), and on their relative influence in shaping urban development. As used in this volume, the phrases "economic forces" and "marketplace activities" refer to the actions of private economic units.

The "political aspect" of human behavior is not, however, the same as "the activities of governmental units"; nor is the "economic aspect" coextensive wih the activities of private economic units. "Political aspect" and "economic aspect" do not denote concrete organizations or people; they refer to different ways of looking at the same concrete organizations. The political aspect of any organization refers to the activities of its members as viewed in terms of power andresponsibility (within the organization, and in the broader society). Thus the role of General Motors and other private economic units can be fully understood only if such units are viewed from political as well as economic perspectives. Similarly, the economic aspect of any organization refers to the ways that its activities involve and affect the distribution of goods and services in a society. Thus, New York's Port Authority and other governmental units can be analyzed from economic as well as political perspectives.

As these comments suggest, it would be more accurate in most cases to denote an organization as "predominately politically oriented" or "predominately economically oriented." It is even possible that certain governmental units should, based on available evidence, be placed in the "predominately economically oriented" category—although we do not think the evidence on this point is persuasive for any of the governmental units considered in this volume. It is possible also that evidence would show that a particular private corporation acts primarily with reference to its power position, and thus belongs in the category of "predominately politically oriented" organizations. For purpose of this study, the benefits of redefining organizations in this way seem small. Thus we consider the issue of influence on urban development with reference to concrete units as they are commonly denoted—governmental units and private economic organizations.

Our discussion above draws primarily on Marion J. Levy, Jr., Modernization and the Structure of Societies (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1966); see especially pp. 290–293, 333–336, 436 ff., 503 ff. On the interdependence of social factors, see also the discussion of dynamic causation in Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma (New York: Harper and Row, 1944), pp. 75 ff. and Appendix 3.

In general, the relationships among the various forces shaping urban regions can be summarized as follows. First, in the United States and in other democratic societies, there is a close interconnection among individual attitudes, governmental policies, and the actions of economic organizations and individuals in the marketplace. To be sure, consumer and voter preferences are in part shaped and constrained by the activities of large organizations—both governmental and economic—and by the choices they provide. In most instances, however, governmental and marketplace activities respond to values widely shared by the general public, and reinforce each other. The highway-housing example above illustrates these interrelationships.

Second, the extent to which the activities of economic organizations, or the actions of government (and of various levels of government), have a primary role in these interrelationships varies from society to society, depending on several factors. For example, in a nation with a tradition of governmental planning of economic and urban affairs, and with a history of public owner-ship of urban land—such as Sweden—public policies are more likely to have substantial influence on urban development than in a country without such traditions.[23] In the United States, the following factors are among the most important in relation to the development issue:

1. considerable emphasis on individualism and competitiveness in social relationships generally;

2. a system of vigorous private economic organizations;

3. historically, a low level of governmental involvement in economic affairs, in comparison with many other modernized societies;

4. substantial diffusion of governmental responsibility among semiautonomous local, state, and national units;

[23] See Thomas J. Anton, Governing Greater Stockholm: A Study of Policy Development and System Change (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1975); as well as Goran Sidenbladh, "Stockholm: A Planned City," in Cities: A Scientific American Book (New York: Knopf, 1966), pp. 75–87; Andrew Shonfield, Modern Capitalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1965), pp. 199–211; and Thomas J. Anton, "Incrementalism in Utopia," Urban Affairs Quarterly 5 (September, 1969), pp. 59–82.

5. a continuing increase in governmental involvement in economic and other aspects of American society in recent decades, combined with closer relations among the several levels of government—thus modifying factors (3) and (4);

6. a tendency for significant governmental action to focus on specific problems, particularly as those problems reach a state of widely perceived "crisis";

7. governmental action, especially in noncrisis situations, that is responsive primarily to the concerns of organized and politically active interest groups; and

8. a greater emphasis (in governmental affairs and otherwise) on concrete, measurable goals and achievements than on esthetic and other less readily measured aspects.[24]

Third, the pattern of urban development is the result of a dynamic interplay of forces, some going beyond social preferences, government actions, and activities of economic organizations. Most prominent perhaps is the influence of technology. The impact of the railroad and the motor vehicle on the patterns of industrial and residential location are obvious examples.

Fourth, while it is sometimes convenient to refer simply to the activities of "government" and of "economic organizations," neither term refers to a cohesive group with a coherent set of development goals. On the contrary, different views on important issues generate wide divisions and conflict among public agencies and within the private sector. In highway and airport construction, state and regional public agencies are often in conflict with local governments and their constituents. To take another example, any new policy initiative involving abandonment, expansion, or added tax dollars for rail service in the region attracts widespread debate among political leaders—often pitting some cities, suburbs, and their state representatives against others, as they examine closely the proposed distribution of benefits and burdens.

Since our interest is mainly in understanding the role of government in shaping the New York region, we devote considerable attention to the great diversity of public agencies, and to the patterns of alliance and conflict among them. Indeed, the role of private actors occasionally fades into the background, as public entrepreneurs and opposing officials take center stage. Like public agencies, however, private interests also divide, often sharply, as we illustrate in the following chapters. Merchants in Newark resist mass-transit projects that may siphon off their shoppers to Manhattan, whose chambers of commerce applaud public action which would yield such benefits. Business leaders who see regional vitality and increased profits for their banks and other enterprises in the construction of new shopping malls, a world trade

[24] On values and attitudes in the United States, see Dahl, Democracy in the United States, especially Chapter 22; Gabriel A. Almond and Sidney Verba, The Civic Culture (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1963); E. E. Schattschneider, The Semi-Sovereign People (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1960). The impact on urban development of American attitudes toward private property and private enterprise is treated in Sam Bass Warner, The Private City (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1968). For an interesting contrast between the emphasis on individualism and competition in the United States and the very different situation in Norway, see Harry Eckstein, Division and Cohesion in Democracy: A Study of Norway (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1966), especially pp. 80–89, 184.

center, or a new commercial complex in the New Jersey meadows, find themselves opposed by shopkeepers likely to be uprooted or drained of their customers. And both sides find ready allies among elected officials and public agencies whose own concerns—votes, highway expansion, environmentalism—seem likely to be aided or imperiled as a new project goes forward.

From the vantage point suggested by Wood, however, these divisions and intertwinings of public and private organizations can be considered relatively unimportant in assessing the role of government. The appropriate test for meaningful governmental influence in urban development, he argues, is "public direction of economic growth." More specifically,

[this] would involve the establishment of a governmental structure which possessed the jurisdiction and the authority to make decisions about alternative forms of Regional development, more or less consciously and more or less comprehensively. . . . There would be some type of Regional organization empowered to set aside land for recreational purposes on the basis of a Regional plan. . . . There would be some type of Regional organization empowered to subsidize commuter transportation, if this were in accord with a general plan. . . .[25]

According to this view, government must be able to plan and act on a comprehensive basis for the entire region, in order to influence development in a significant fashion. If it lacks this capacity government is left in a position of "little consequence," while economic forces and other factors shape urban development.[26]

Varieties of Influence

Government's role in urban development is far more varied than Wood's approach suggests. The major patterns of governmental influence can be expressed better in terms of a continuum than a dichotomy—as shown in Figure 1. At one end of the continuum, government officials merely ratify decisions made in the private marketplace. Typical are the actions of local officials in zoning vacant land to the specifications of developers who wish to construct

[25] Wood, 1400 Governments, pp. 174–175, 192. Cf. 171, 193 ff. Wood implies, especially on p. 192, that the standards for governmental action quoted in the text above are those advocated by reformers, and are not necessarily his own. In context, however, they appear to be the standards for a significant governmental role accepted in 1400 Governments .

[26] Wood's volume focused primarily on the nature of contemporary urban problems and programs, not on the reforms needed to alter current developmental trends. When advocates of reform approach urban problems with a lens similar to that used by Wood, the result is unrealistic and often confused proposals. That is, the reformer argues that regional development is shaped by two forces, the private market and government policy, the marketplace presently being the dominant force. He then tends to argue that existing urban problems (suburban sprawl, deterioration of the older cities, etc.) result from the dominant role of the market. The solution, then, is action by the other force—government—to counter market pressures and to substitute "rational" or "efficient" urban growth for the irrationality of the marketplace. Such public action, the reformer argues, is likely to be especially effective if undertaken by regional, state and federal agencies, with their broader perspectives (and perhaps broader powers and financial resources). If, as we argue, the actions of economic organizations and government are closely intertwined with underlying social preferences, the reformers' plea must be interpreted as an argument that the urban populace ought to substitute other values—presumably the "rationality" values of the urban planner—for the values that have previously guided economic and political behavior in the metropolis.

Figure 1

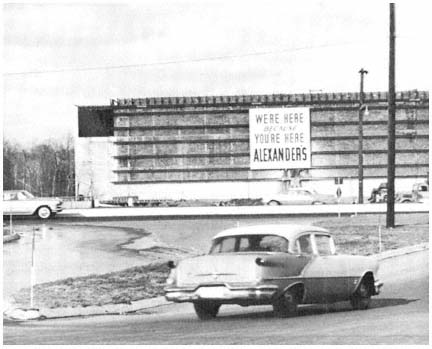

single-family homes on small lots, or the activities of local governments in facilitating private development of downtown parking lots that enhance the ability of main street merchants to compete with suburban shopping centers.

In the middle range of the continuum, a government unit is highly sensitive to economic and social forces, but contributes significantly to the specific content of the policy decision. Included here are the frequent situations in which demands for government action are relatively unfocused. Rapidly increasing automobile ownership creates the demand for new highways, but the appropriate government agencies must translate this unfocused demand into priorities and specific highway alignments. The same is true of demands for increased water supply or a new jetport. In each case, the specific content of the governmental decision will influence the subsequent pattern of development in the affected area. For instance, because a Garden State Parkway interchange was constructed in Paramus, that town became highly attractive for commercial development, and during the 1960s blossomed into one of the major shopping areas in northern New Jersey.

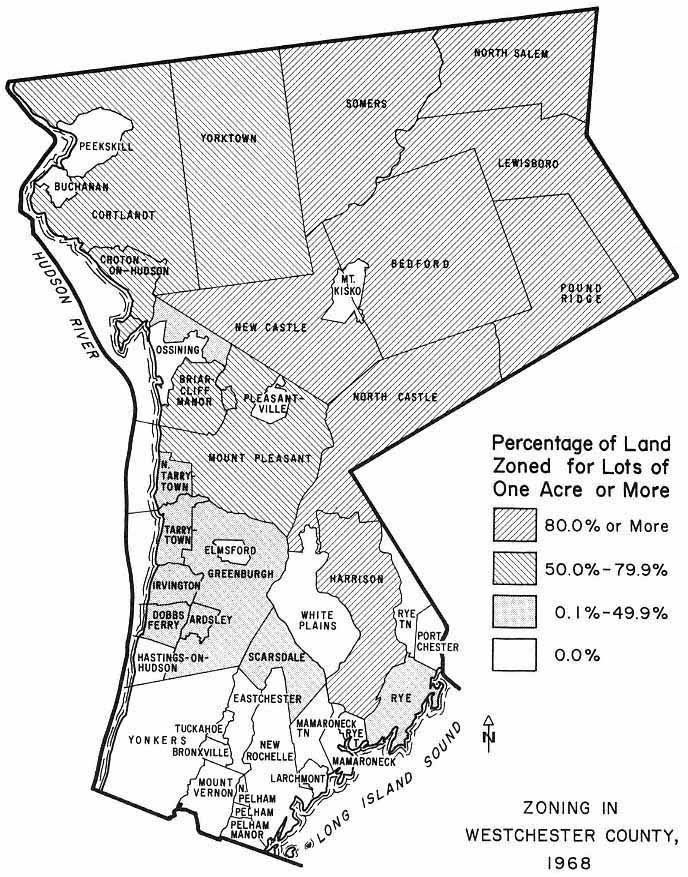

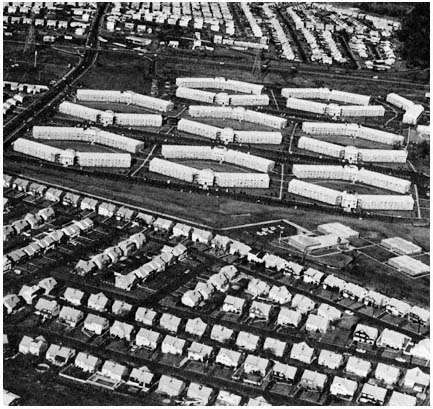

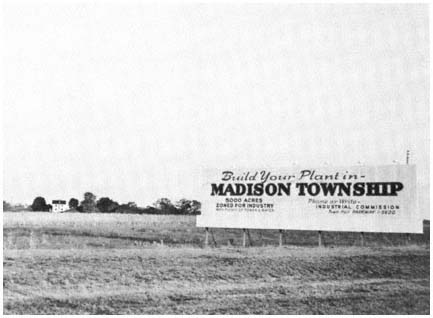

A more significant type of government influence on urban development occurs when a governmental unit's sensitivity to economic and social developments modifies or amplifies developmental trends. An example of this kind of governmental action is the use of restrictive zoning ordinances and building codes by suburban municipalities to prevent the construction of moderately priced, single-family housing. This type of zoning results from the awareness on the part of suburban officials and taxpayers that the private marketplace, if not restricted, will attempt to satisfy the lower-income family's quest for space and privacy with relatively inexpensive houses on small lots. Such homes threaten to cost the community more in services than they can generate in taxes, as do apartments priced for less affluent families. The use of minimum lot-size and other zoning restrictions to limit population—now an almost universal practice in the New York region—constrains the ability of real estate developers to maximize their investments through intensive development of suburban land. Such local government policies have significantly amplified the outward spread of residences and jobs in the region. The remaining land zoned for small houses, inexpensive apartments, and mobile homes tends to be located on the periphery of the region, where the local political systems are not yet sensitive to the costs of intensive suburbanization. These government policies also modify the effective demand for suburban housing, since many lower-income families are both dissuaded by the high cost of homes in suburbs situated close to the region's job centers, and discouraged by the journey-to-work associated with less expensive suburban housing forty miles or more from the core. In short, even in the middle range of this continuum, government decisions significantly influence development patterns.

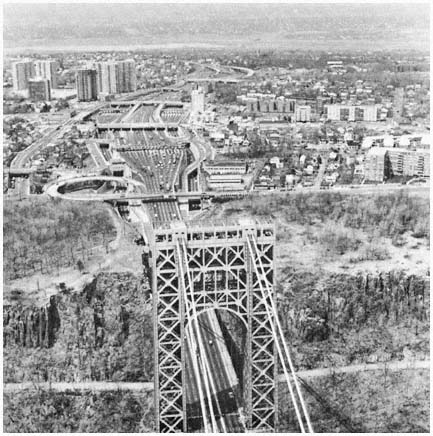

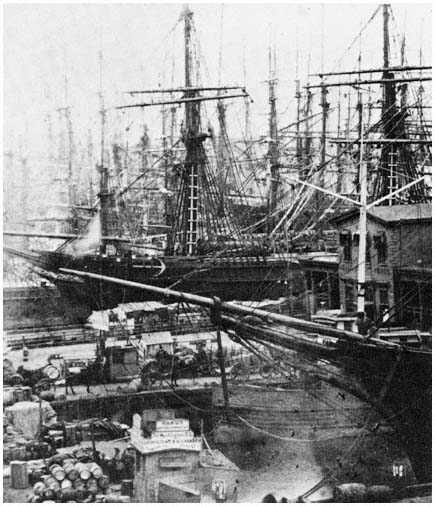

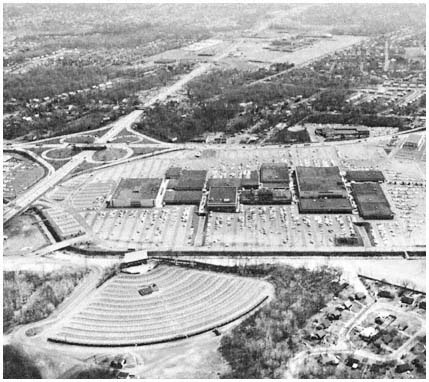

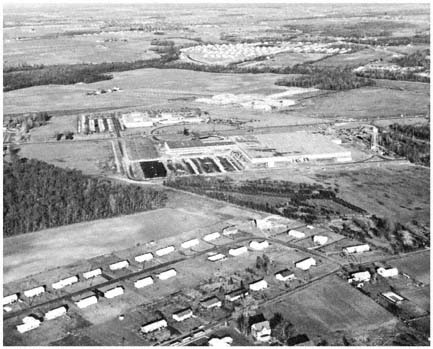

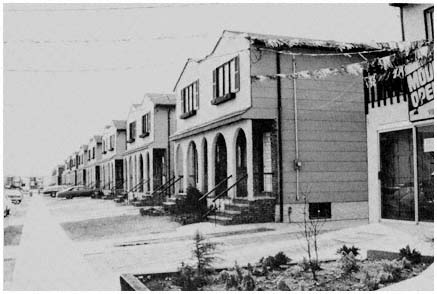

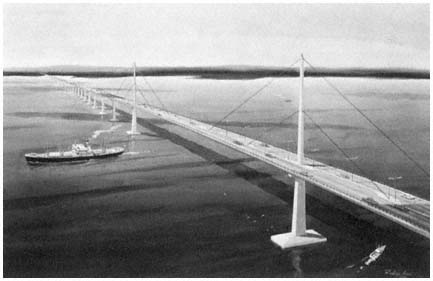

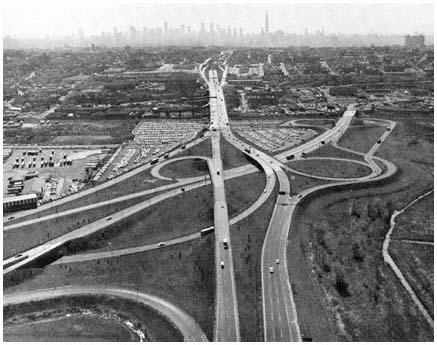

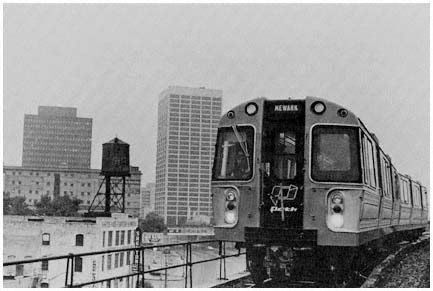

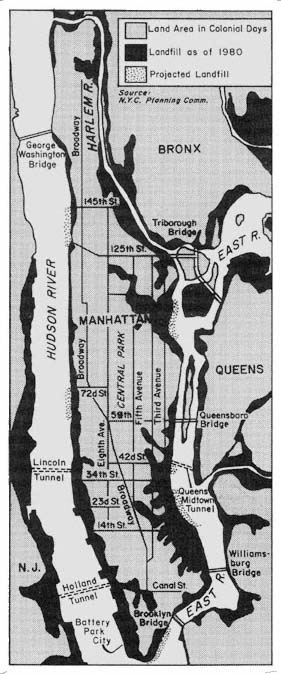

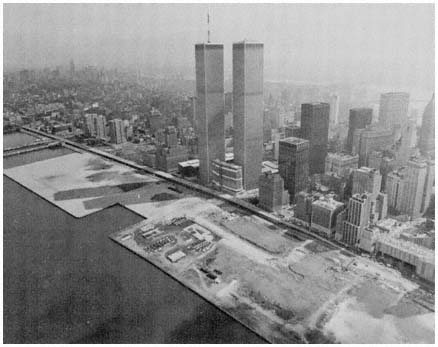

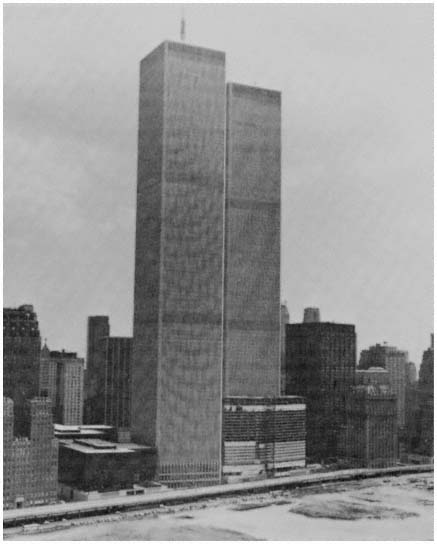

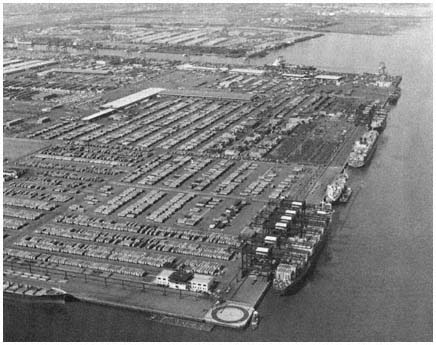

The interests and actions of public agencies such

as the Port Authority determine when and where

major public facilities are constructed, thus

affecting the location and timing of development

like that around the New Jersey end of the

George Washington Bridge.

Credit: Louis B. Schlivek, Regional Plan Association

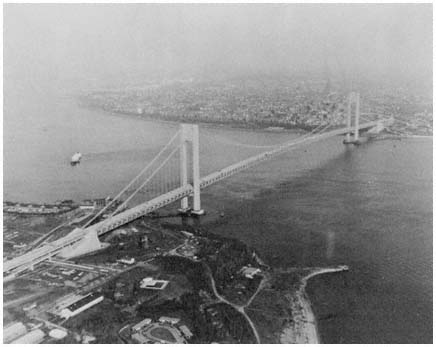

Toward the other end of the continuum, government actions have a critical initiating role in shaping development. For example, early in the region's history New York State decided in 1816 to sell $8.5 million in bonds for a canal linking Lake Erie and the Hudson River. Completed in 1825, the 364-mile Erie Canal brought the old Northwest to New York's doorstep, giving the region a tremendous early competitive advantage. More recently, the redevelopment of Columbus Circle and the building of the Lincoln Center complex in Manhattan, the construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge with its strong impact on development on Staten Island, the development of parks and beaches on Long Island, and the maintenance of much of northern Westchester County as a low-density, semirural enclave illustrate government acting as an important and relatively autonomous force in shaping the New York region.

Government's influence on urban development in the region thus appears to be considerably more significant than Wood's conclusions would lead one to believe. In general, we concur with Charles Abrams's view that "public policy for slum clearance, housing, race discrimination, zoning, road building, community facilities, transportation, suburban development, relief of poverty, and for spending and taxation is a main lever in manipulating the patterns of the society and the choices available to its members."[27] In a relatively responsive democratic political system such as that of the New York region, however, government's use of these levers is constrained by the developmental values which are widely shared or vigorously advanced. As a result, those who do not share the dominant social values, or have the resources to press their views, necessarily find it very difficult to employ government as an instrument to further their goals in urban development. But the situation is dynamic rather than static, because widely shared values and the capabilities to advance views change over time. As illustrated in the chapters that follow, public attitudes about the environment changed substantially in the 1970s, reducing consensus on the desirability of highway construction, while minority and lower-income groups in the region's older cities significantly increased their ability to persuade public development agencies to take account of their values.

Varieties of Influence: A Further Look

The attentive reader will have noticed that Robert Wood's discussion of influence and our continuum both involve two variables—the impact of governmental action on urban development, and the independence of governmental action (particularly in relation to "private economic forces"). In the discussion above, these two variables have not been considered separately. Because of the interrelationships among social-political-economic factors, it is empirically difficult to sort out the "independence" variable. Also, our analysis in the following chapters devotes substantial attention to governmental activities that rank highly in both impact and independence, since these activities provide the clearest evidence with which to challenge the Wood-Vernon position.

Nevertheless, the chapters below do discuss some governmental units and activities—such as general governmental units in older cities—whose ranking in terms of the two variables may be quite disparate. In any event, exploring the relationship between "independence" and "impact" may help improve analytical clarity.