Preferred Citation: Weiner, Douglas R. A Little Corner of Freedom: Russian Nature Protection from Stalin to Gorbachev. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, c1999 1999. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1m3nb0zw/

| A Little Corner of FreedomRussian Nature Protection from Stalin to GorbachëvDouglas R. WeinerUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1999 The Regents of the University of California |

To my angels:

Loren and Pat, Feliks and Nadia, Nikolai and Elena,

Olga, Konstantin, and Dania

Preferred Citation: Weiner, Douglas R. A Little Corner of Freedom: Russian Nature Protection from Stalin to Gorbachev. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, c1999 1999. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1m3nb0zw/

To my angels:

Loren and Pat, Feliks and Nadia, Nikolai and Elena,

Olga, Konstantin, and Dania

Acknowledgments

I have been fortunate to have been able to spend considerable amounts of time living and researching in the Soviet Union and its successor states. For that I am indebted to the generous support of a number of granting agencies and foundations that have had faith that this project would one day see the light of day. A trip to the USSR in 1986 was supported by the National Academy of Sciences. IREX and the National Council for Soviet and East European Studies (contract 806–28), a Title VIII program, generously funded a key second research trip for ten months in 1990–1991 plus summer support. From June to August 1991 I had the good fortune to be a fellow at the Kennan Institute of the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., allowing me to reflect on the materials I had just acquired and also to obtain other materials at the Library of Congress. To its director, Dr. Blair Ruble, to the administrative assistant, Monique Principi, to my research assistant, Jason Antevil, and to the Kennan's entire staff, my enduring thanks. The Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy under its former director, Helen Ingram, and its deputy director, Robert Varady, provided a warm and stimulating atmosphere where the writing continued. Finally, the Spencer Foundation (grant no. 9500933) generously provided the opportunity for me to complete the writing of this book during my sabbatical year, even as I began yet another book project with that foundation's kind support. Each of these funding sources has my deep and sincere gratitude.

As a result of liberalization within the Soviet Union and its successor states, I was able to use a vastly larger range of sources than I could have (and did) ten years ago. Owing to the kind efforts of the then Soviet minister for environmental protection, Dr. Nikolai Nikolaevich Vorontsov, I became the first foreigner to use the archives of the Council of Ministers of the Russian Republic, housed in the former TsGA RSFSR (Central State Archives of the

RSFSR). I am glad to report that the exceptionally warm atmosphere set by Tat'iana Gennadievna Baranchenko, Natal'a Petrovna Voronova, and Liudmila Gennadievna continues to this day. Additional archival sources include: GARF (State Archives of the Russian Federation, formerly TsGAOR), RGAE (State Archives of the Russian Economy, formerly TsGANKh, with special thanks to its deputy director, Valentina Ivanovna Ponomarëva), TsKhDMO (Center for the Preservation of Documents of Youth Organizations, formerly the Komsomol Archive), ARAN (Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, both the Moscow and St. Petersburg branches, and its photo lab LAFOKI), RTsKhIDNI (Center for the Preservation and Study of Documents of Recent History, formerly the CPSU Archives), TsKhSD (Center for the Preservation of Contemporary Documentation, formerly the Central Committee CPSU Archives), the Archives and Library of the Moscow Society of Naturalists (MOIP), The Ukrainian Central State Archives, the Library of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, the Russian State Library (Saltykov-Shchedrin), the Russian Federation Library (formerly the Lenin Library), and the Library of the Russian Geographical Society. The archival staffs have been generous and supportive far beyond the norms of professional courtesy. I am indebted to these women and men beyond words. To Nina Vladimirovna Dem'ianenko of the MOIP Library and Archives, my special thanks.

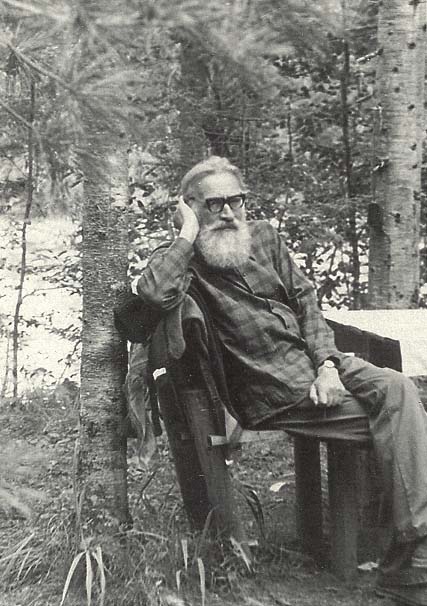

Documentation was supplemented by numerous interviews with veterans of the movement conducted in Russia, Ukraine, and Estonia. Some of these were conducted in zapovedniki , or nature reserves (Prioksko-Terrasnyi, Tsentral'no-Lesnoi, Askania-Nova). To my informants, Academy of Sciences vice president Aleksandr Leonidovich Ianshin, Ksenia Avilova, Tat'iana Leonidovna Borodulina, Galina Borisovna Chernousova, Nelia Efimovna Dragobych, Iurii (Georgii) Konstantinovich Efremov, Oleg Kirillovich Gusev, Dmitrii Nikolaevich Kavtaradze, Viktor Masing, the late Andrei Aleksandrovich Nasimovich, Vitalii Feodos'evich Parfënov, Evgenii Makarovich Podol'skii, Linda Poots, Evgenii Arkad'evich Shvarts, Vladimir Vladimirovich Stanchinskii Jr., Vadim Nikolaevich Tikhomirov, the late Mikhail Aleksandrovich Zablotskii, Iurii Andreevich Zhdanov, and Sergei Vladimirovich Zonn, I owe a huge debt of gratitude. Konstantin Mikhailovich Efron has given me encouragement and friendship as well as the gift of his inestimable knowledge and wisdom.

The wisdom and friendship of my colleagues in Eurasia greatly assisted me to a more sophisticated understanding of the materials I had collected. They have given me more than I can ever hope to repay. Daniil Aleksandrovich Aleksandrov has played an immense role in encouraging me, among other things, to distinguish clearly between civic and scientific activism. This advice has been invaluable. Feliks and Nadia Shtil'mark, as always, have been the truest friends and most knowing commentators on the history of Rus-

sian nature protection. For those who seek a definitive history of the zapovedniki as institutions, there is only one book, and that is by Feliks Robertovich Shtil'mark. Vladimir Evgen'evich Boreiko also deserves more than mere mention. A man of big vision, he has been a creative and encouraging coexplorer in these relatively uncharted waters who has unstintingly shared his findings with me. Owing to his selfless desire to get the truth out, he has given collegiality a new dimension. I salute him. Competing with Boreiko for top prize in collegiality is Oleg Nikolaevich Ianitskii, the foremost authority on the modern environmental movements of Eurasia, who has also enriched my understanding with his. Others who have actively helped with this project are my friends and colleagues Aleksei Enverovich Karimov, who provided camaraderie during my last archival blitz, Anton Iur'evich Struchkov, Eduard Nikolaevich Mirzoian, who more than once gave me an institutional home in Moscow, Eduard Izraelovich Kolchinskii, who did the same in St. Petersburg, Viktor Kuz'mich Abalakin, Nelia Drogobych, Elena Vsevolodovna Dubinina, Nikolai Aleksandrovich Formozov, Mikhail Vladimirovich Geptner, Tat'iana Gerasimenko and Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Volkov, Elena Kriukova, Aleksei Vladimirovich Iablokov, Elena Alekseevna Liapunova, Nikolai Daniilovich Kruglov, Nina Trofimovna Nechaeva, Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal, Kirill Rossiianov, Ol'ga Leonidovna Rossolimo, Veronika Vladimirovna Stanchinskaia, Hain Tankler, Marshida Iunusovna Treus, Vladimir and Svetlana Zakharov, and countless other friends too numerous to mention. I owe special thanks to Aleksandr Sergeevich Rautian, who single-handedly saved the invaluable Viazhlinskii collection of photographs of conservation activists from the 1920s through the 1950s and who allowed me to reproduce them.

Colleagues on this side of the ocean also helped to clarify my thoughts and challenge dubious assertions. I am indebted to Valery N. Soyfer and to Stephen Kotkin for insisting as strongly as they did that the scientists' professions of Soviet patriotism might well be genuine and that it was impossible not to be, at least in small part, a "Soviet" person. The recommendations of Loren R. Graham, my lifelong friend and quondam mentor, have also found their way into this book. A conversation with Mike Urban led me to examine rhetoric as positioning, and even further incisions followed a generous critique of the introduction by my colleague Hermann Rebel. Upstairs in the sociology department, Elisabeth Clemens, truly a magician, read part of the manuscript and offered great recommendations for tightening it. Janet Rabinowitch valiantly read it twice, offering key suggestions, and Susan Solomon provided valuable guidelines for framing the story. To executive editor and publishing magician Howard Boyer go my heartfelt thanks for believing in this book and championing it. Erika Büky shepherded the manuscript through its production with a swift and sure hand, while Madeleine Adams's elegant copyediting made it infinitely more readable.

Finally, my thanks to those who have stood by me all these obsessive years—my wonderful friends, Mars (the world's leading cat), and my loving parents. Finally, I would like to thank you, the reader, who risked inguinal hernia and other bodily harm to pick up this too, too solid tome.

Introduction

In those times scientific and other publics showed their various colors-more often than not straining to approve [the decisions of the regime]; on occasion, however, even during the most difficult years, some stood up to the arbitrary use of power and to ignorance. People were expected to praise the transformation of nature under Stalin and Khrushchëv, to fetishize those programs as ones that supposedly only brought improvements . . . But geographers cleverly devised ways to oppose these transformations even in the years of "The Great Stalin Plan. "Is it possible that there were people that brave?

Iurii Konstantinovich Efremov

When we speak about our public opinion, then it is necessary first of all to speak about scientific public opinion.

Sergei Pavlovich Zalygin

This book is an attempt to come to grips with some very surprising archival findings. As I continued my research on the Russian nature protection movement forward in time from the years of the Cultural Revolution and the First Five-Year Plan (1928–1932), I repeatedly came across documents that testified to the unlikely survival of an independent, critical-minded, scientist-led movement for nature protection clear through the Stalin years and beyond. Through a number of societies controlled by botanists, zoologists, and geographers, preeminently the All-Russian Society for the Protection of Nature (VOOP), the Moscow Society of Naturalists (MOIP), the Moscow branch of the Geographical Society of the USSR (MGO), and the All-Union Botanical Society, alternative visions of land use, resource exploitation, habitat protection, and development were sustained and even publicly put forward. In sharp contrast to general Soviet practices, these societies prided themselves on their traditions of contested elections for officers on the basis of the secret ballot, their foreign contacts, and their prerevolutionary heritage.

To gain a sense of the boldness of these activists consider that in June 1937 the leadership of VOOP drafted a letter to Central Committee secretary A. A. Andreev seeking a meeting to upgrade the Party's commitment to nature protection and requesting authorization to travel to an international conference on conservation in Vienna set for the following year.

That very week the high command of the Red Army had been arrested, accused of working for a foreign power. Two months earlier the Soviet government had written to the International Genetics Committee postponing the Sixth International Genetics Congress, scheduled for August 1937, to some unspecified time during the next year. Stalin was shutting down the country to the outside world, and foreign contacts in one's past left Soviet citizens open to the charge of treason. An atmosphere of terror was settling on the gigantic country. And yet these scientist-activists wanted to go to Vienna! Another VOOP document dating from July 1948 reveals that the society's leaders wrote directly to the USSR Ministry of State Security to question why secret police detachments were chopping down all of the cypress trees in the Crimea. And in May 1954, barely one year after Stalin's death, the scientists' societies organized a protest meeting demanding the restoration of nature reserves eliminated three years earlier by Stalin.

Just as eye-catching were telegrams from oblast' (provincial) Party and government leaders "categorically opposing" those 1951 "liquidations" of the reserves at the time. Also in the archives is evidence of a number of dramatic intercessions by a succession of Russian Republic (RSFSR) premiers to protect the nature protection society itself from elimination at the hands of Kremlin authorities. Ukrainian and other archives have confirmed that such patronage by republic–and oblast' -level authorities of the nature protection movement was not limited to the RSFSR.

This book describes a succession of independent social movements for nature protection that predated and survived Stalin and all of his Soviet successors.[1] With protection from republic–and provincial-level patrons, this movement was institutionalized in a number of scientific and voluntary societies and for a time was also able operationally to control a twelve million-hectare (thirty million-acre) network of zapovedniki (scientific nature reserves), which acquired symbolic importance as a unique "archipelago of freedom" within the GULAG-state.

The reader may well ask how it was possible that any such movement, its institutions, and the energetic protection of them by provincial–and republic-level politicians could have existed in Stalin's terror state. Indeed, historians and Soviet specialists overwhelmingly deny that such a movement and network of patrons could have existed. For example, the social historian Geoffrey Hosking asserts:

The Soviet Union . . . was a uniquely centralised polity, in which the Party-state apparatus governed not only the aspects of society normally associated with authority, but also the economy, culture, science, education, and the media. . . . Social interest groups had no identity separate from the nomenklatura hierarchy, so there was no question of their formulating their distinct interests, let alone of forming associations in order to defend them. That constituted the strength of the system.[2]

But Stalin and his successors did not root out all such autonomous social groups. Although we lack conclusive answers as to why the nature protection movement was not obliterated along with other institutional sources of political, cultural, and moral dissent or deviation, the following pages suggest some promising avenues of explanation. Perhaps as more archival materials become available and are examined we will find better answers. The very fact that independent social organizations continued to exist through the Stalin period and after raises fundamental questions about the Soviet system: Were there other areas of social organization besides nature protection that were able to survive as something more than naked transmission belts of regime values? Was it the regime's intention to extirpate every expression of divergent views and every manifestation of social autonomy? If so, then the persistence of various nature protection movements seems to indicate a certain lack of efficiency of Soviet rulers in the face of subjects determined to defend their autonomous selfhood. If not, we must come up with a more sophisticated picture of how Stalin and his colleagues expected to maintain effective control over society. Could the continued existence of this apparently autonomous nature protection movement actually have served the interests of the Party-state? More broadly, what changes in our picture of Soviet society and politics do these archival findings move us to consider?

In earlier works I have argued that the Soviet conservation movement in the 1920s and 1930s represented a means by which a section of educated society tried to moderate, or even halt, the juggernaut of Stalinist industrialization and social change.[3] Armed with unprovable holistic ecological doctrines that asserted that pristine nature was composed of geographically bounded closed systems ("biocenoses") that existed in states of equilibrium and harmony, conservationists warned of the dire consequences to the stability of those natural systems as a result of collectivization, industrialization, and other Stalin-era projects. They averred that only they, through their expert study of long-term ecological dynamics of pristine natural communities, could determine appropriate economic activities for specific natural regions of the USSR. They began to conduct this study in specialized protected territories—zapovedniki —which were off-limits to any uses except scientific research on ecological/evolutionary problems. Conservation activists, led by the foremost field biologists in the country, sought first to obtain, and then sustain, the right to a veto over unacceptable economic policies through the newly created Interagency State Committee for Nature Protection. At the same time they struggled to retain control of and to expand the network of zapovedniki .

As Stalin's revolution from above from 1928 to 1933 turned the country on its ear, nature protection emerged as a means of registering opposition

to aspects of industrial and agricultural policy while remaining outwardly apolitical; arguments were couched in the language of scientific ecology. The picture ecologists drew of fragile self-regulating biocenoses seemed to throw cold water over the Stalinists' plans for a successful total mastery and transformation of nature.

Unlike the situation under Lenin and during the NEP (New Economic Policy),[4] scientists now found their own professional freedom under mortal threat. Moreover, on some level they perhaps understood the linkage between Stalin's plans for shackling nature and the reenserfment of society. Prominent Soviet scientists responded by marshaling ecological arguments against collectivization, acclimatization, and the great earth-moving projects. When this scientific opposition to the Five-Year Plan failed, scientists retreated to their ultimate fall-back position: a defense of the inviolable zapovedniki under their control.

By their charters the zapovedniki were absolutely inviolable. They had become the symbolic embodiment of the harmony of communities, of natural (and human) diversity, and of the free and untutored flow of life (in Anton Struchkov's eloquent phrase, the "unquenchable hearths of the freedom of Being"). As long as the "pristine" zapovedniki could remain independent, what was denied to human society in Stalin's Russia could be preserved in symbolic, natural form in these reserves. They formed an archipelago of freedom, a geography of hope.

Particularly revealing in this regard are the comments of Sergei Zalygin, repentant hydrologist, conservation activist, and editor in chief of Novyi mir , Russia's leading cultural-literary monthly: "Here is the crux of the matter: the word 'zapovednik ' means 'a parcel of land or marine territory completely and eternally taken out of economic use and placed under the protection of the state."' But zapovedniki are much more than that: "A zapovednik is something sacred and indestructible, not only in nature but in the human being itself; it is also a commandment, a sacred vow [from its root, zapoved ']. And it is precisely around these meanings that the struggle over the zapovednik raged and indeed rages at the present time. . . . [T]he zapovedniki remained some kind of islands of freedom in that concentration-camp world which was later given the name 'the GULAG archipelago.'"[5]

If the defense of these inviolable institutions had become the paramount aim of Russia's elite natural scientists, such a defense required justification in biological theory. Of the two ecological paradigms available at the time the individualistic or continuum theory of species distribution, and the paradigm of discrete, bounded, fragile, highly ordered ecological communities in a homeostatic equilibrium—only the latter fit with the research agenda of the zapovedniki and could provide a justification for absolute inviolability. However, we are struck by the disparity, in Gerovitch and Struchkov's words, "between the rather weak 'scientific' arguments for absolute inviolability, on

the one hand, and the inspiration with which this idea was defended, on the other hand."[6] Even after a Stalinist campaign forced the Zapovednik Administration of the RSFSR to renounce "inviolability" in principle and to accept a new mission for the reserves—the transformation of their "pristine" nature into the more productive "Communist nature" of the future—the scientific establishment and its patrons in the Zapovednik Administration continued to defend the "sacred" reserves from their "profane" new tasks in practice. Indeed, the struggle over the defense and later the reestablishment of inviolable zapovedniki eclipsed all other environmental issues through the mid-1960s, and through the 1970s if we include Baikal, which was also a part of the geography of hope.[7]

This book confirms and develops these ideas. The early movement, which described itself as "nauchnaia obshchestvennost "' (scientific public opinion), a self-designation that connoted a social identity with its own values, traditions, interests, and ethical norms,[8] does not derive its sole historical importance from its accomplishments in the areas of species protection, landscape preservation, and support for multidisciplinary and unique ecological research in the zapovedniki . Perhaps its greatest significance for Soviet society resides in its role as an institutional "keeper of the flame" of civic involvement independent of the Party's dictates.

Activists maintained an atmosphere of internal democracy within the societies that they controlled: the All-Russian Society for the Protection of Nature (VOOP), the Moscow Society of Naturalists (MOIP), the All-Union Botanical Society, and the Moscow branch of the Geographical Society of the USSR (MGO). The epicenter of this movement was the Zoological Museum of Moscow State University, just down the block from the Manezh and Red Square, where MOIP and MGO were headquartered and where VOOP frequently held its meetings. Loren Graham, the historian of Russian science, once remarked that hundreds of Western scholars, diplomats, and journalists had long wondered whether there was any "island of freedom" in the Soviet Union, unknowingly driving right past it thousands of times!

This study underscores the resilience, courage, and determination of the nature protection activists, whose leading members were drawn mostly from the elite ranks of Soviet field biology (laboratory-based biologists and scientists from chemistry and physics were less well represented, although there was a fair contingent of geologists and soil scientists). In 1953—1955, when control over VOOP was wrested from them and placed in the hands of Party stalwarts, activists transferred their activity to MOIP, still under the control of their own people. This study also reveals their determined and creative efforts to pass on their ethos of nauchnaia obshchestvennost '—with its connotations of activism, service to Science, broad erudition, scientific autonomy, individual responsibility, and collective action—to succeeding generations. The most important vehicles for this were the instructional programs in field

biology for children and teenagers run by the Moscow Zoo (KIuBZ), VOOP, and MOIP. Not coincidentally, today's leading zoologists and botanists, who include some of the most prominent reformist politicians such as Nikolai Vorontsov and Aleksei Iablokov, were molded in these intellectual non-Party youth groups.

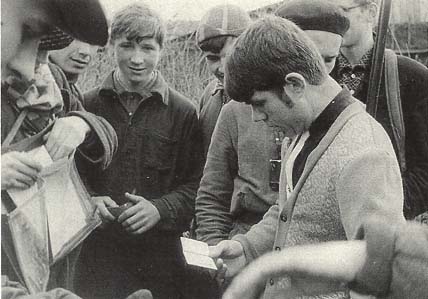

In Russia, MOIP took the leading role in the creation of the first student brigade for nature protection (druzhina po okhrane prirody ) in the Biological Faculty of Moscow State University in 1960, whose membership varied from 25 to 150 over the next thirty years.[9] Soon, almost all major universities and elite technical schools boasted druzhiny , which collectively reached a membership of about 5,000 by the 1980s.[10] These perpetuated at least some portion of the old prerevolutionary ethos of the "botanical-zoological-geographical intelligentsia." Members of the student brigades engaged in measuring point sources of air and water pollution, monitoring compliance with environmental laws, detaining poachers, and planning new nature reserves. Seeking idealistically at first to enforce laws that were already on the books, they soon discovered that the system was not interested in their "help"; indeed, their attempts to hold managers and hunters to the law was viewed by the authorities as oppositionist and slightly subversive. By and large, druzhinniki continued in the more Western–and global-oriented perspectives of their mentors.

At times, the movement served as a counterculture in that it provided for its members' most important social needs, which the larger society had failed to meet. Central were the needs felt by those who joined to be self-directed and autonomous of authority, to engage in genuinely creative work, and to serve the broader society—a variant of the old nobility's and intelligentsia's ideal of service.

"Self-sufficiency," emphasized Oleg Ianitskii, a leading social-movement sociologist, "lies at the core of the values embraced by environmentalists; they understand independence as a way of life, as a mode of everyday existence. . . . At the heart of the value-orientation described above is intelligent, creative activity." Ianitskii used the Marxian expression "unalienated labor" to describe the work of activists. Above all, this social identity was a path to a kind of "self-realization" as an individual. Activists, observed Ianitskii, "perceive independent activity as a search for meaning in life, as a testing of alternative possibilities for realizing their personal identity."[11]

The result of the efforts of the individuals examined in this study was the creation and perpetuation of significant communities that sustained their members—creative personalities who would otherwise have been ground down by the conformist, repressive Party-state system. As late as the early 1990s, Ianitskii could write:

Environmentalists remain a united community, above all in terms of their values and psychology. Whatever the future might hold, the great advantage en-

joyed by all those who make up the movement is that they have already found their place in life. They have discovered their goal and have linked up with fellow-thinkers. As a result, they have the inner calm and assurance of people who are aware of their path. . . . In these small circles people felt their strength, and realized that the System was not so monolithic after all. The members of the groups overcame their sense of inferiority, of their superfluity where the System was concerned. In a society without legal guarantees they acquired a real measure of social defense precisely because they became a community, that is, a genuine collective entity.[12]

Ianitskii points out the mutually reinforcing nature of the social movement and the professional background of its members. The process was iterative:

The resistance put up by the clubs to official dictates is not only the result of the general causes cited earlier, but also has professional and ethical origins. The first of these is the feeling of members that they are participating in serious scientific work that can benefit both nature and humanity. The young biologists' clubs have really been much more than clubs in the usual sense of this word. Their key activity has not been holding meetings but getting out into the field. Many of today's environmental activists have been accustomed from childhood to taking part in expeditions and to carrying on collective work in the midst of nature. The second reason behind the resilience of these clubs is the extremely powerful ethic of group loyalty that operates within them.[13]

The British historian Geoffrey Hosking extends this self-confident moral authority to writers: "Like scientists, writers had both the moral and the social standing to make their opinions felt even in a highly repressive system. The tradition of the writer as an 'alternative government' had been established already in tsarist Russia. The Soviet government had tried to prevent the resurgence of any such 'alternative' by creating its own literary monopoly through the Writers' Union. But even this was, paradoxically, a tribute to the power of the word."[14]

This study points to a crucial difference between writers and field biologists, however. Undeniably, a number of individuals—Akhmatova, Pasternak, Kaverin, perhaps Paustovskii, and later, Pomerants, Dudintsev, Ovechkin, and others—refused to cave in to the regime's demands that literature be put at its service. But if they were an "alternative government," they had no shadow cabinet, no meeting lodge, no debates or elections, no general assemblies. And they could not. Regime surveillance of writers was so overwhelming that there was only the testimony of lone, brave individuals. Certainly, they had their networks of friends and their literary "circles," but that social site was tiny. And with the high rates of arrest, exile, or transfers "on assignment," it was also discontinuous in time and space. Writers left a written legacy, but that was not the same as an organically functioning social movement.

Equally important, the proportion of writers from the high intelligentsia or those converted to its social identity dropped sharply during the Stalin years, swamped by an influx of vydvizhentsy —those promoted upward owing to their more humble social origins plus Party affiliation (those prerevolutionary writers who survived, such as Aleksei N. Tolstoi, did not faithfully represent the older intelligentsia's ethos). At least for the first generation of such parvenus, gratitude to the regime far outweighed any constraints of censorship they may have felt. Only later would these writers feel that their enthusiasm and loyalty were betrayed by the political leaders, particularly in connection with the Party's promotion of policies that seemed to threaten the Russian heartland from which the writers hailed. Consequently, their protest represented not so much an affirmation of the autonomy of creative individuals as a disillusioned turn from Soviet patriotism to Russian nationalism.

Patterns of literary participation in the nature protection cause support these conjectures. Very few littérateurs , even during the 1950s and 1960s, aligned with the scientific intelligentsia's nature protection movement. Konstantin Paustovskii, Oleg Pisarzhevskii, Natalia Il'ina, and Boris Riabinin come to mind. Perhaps Sergei Zalygin should be placed here as well. The majority of writers who have gotten involved in environmental causes are associated with the "Village Prose" school (pochvenniki, derevenshchiki ) and trace their genealogy back to Leonid Leonov and Vladimir Chivilikhin, themselves parvenu writers who began as grateful Soviet patriots and ended as disgruntled Russian nationalists.

"Scientific Public Opinion" in the Light of This Study

Like Russian lawyers after 1917 as depicted by Eugene Huskey,[15] "scientific public opinion" continued to view itself as a kind of professional soslovie , or closed guild. Owing to the corporativist, castelike, and somewhat elitist nature of "scientific public opinion," the scientists that constituted it may hardly be classed as thoroughgoing democrats, despite their observance of democratic norms within their own milieu (although the relationship of the provincial membership, particularly nonscientists, to the scientists who dominated VOOP, for example, is still unclear).

Defying simplistic understanding, the elitism of Soviet intellectuals generally and of scientific public opinion in particular derives from their claims to professional competence and moral vision. Living in a society that historically kept it in a condition of political tutelage, the intelligentsia's sense of moral superiority and purity was a form of psychological compensation for the real power and rights it lacked. While mistrusting the competence and judgment of the "dark masses," scientific public opinion was more resentful of the boorish Party leaders and bureaucratic bosses whom it regarded

as having "hijacked" scientists' rightful role as arbiters of policy. As the sociologist Vladimir Shlapentokh observed, "Being well aware of their high level of education and creative capacity, intellectuals hold elitist attitudes toward others, although in most cases they try to hide them. The elitism of the intellectuals is not, however, directed so much against the masses, but rather toward the ruling class, which is quite often perceived as incompetent and selfish."[16]

The Tightrope Walk of Scientific Public Opinion

Although the complex public behavior of the nature protection movement at times resembled a guerrilla war against the regime, it can also be compared to a tightrope walk. Clearly, scientific public opinion deplored the vulgar attitudes and policy choices of the Stalinist bureaucrats at the center. Nature protection leaders wanted to be invited to assume their rightful places at the policy-making table with responsibility for environmental matters. This was not simply a self-serving wish for power and status; it was part of their professional ethical impulse and sacred duty to serve Science. Once they defined nature protection as a matter for "scientific" rather than political adjudication, a claim accepted by the scientific community at large, protecting the environment also became a sacred duty in the name of Science. Consequently, ethical norms at the very core of scientists' social identity continually impelled scientific public opinion to critique or contest official regime policies toward the environment.

It is also possible that field biologists disproportionately consisted of those who were more intensely attracted to freedom and therefore were prepared to risk more in order to defend the wild.

On the other hand, what enabled the movement to survive in the Stalinist political environment, in addition to serious patronage and protection from enlightened and/or self-interested middle-level political figures, was its perceived harmless marginality. Doubtless Nikita Khrushchëv's depiction of zapovednik naturalists as oddballs (chudaki ) reflected the general views of regime leaders about these field biologists at those very rare times when they even noticed their existence. Despite occasional arrests and episodic characterizations of the movement as a hotbed of counterrevolutionary "bourgeois" professors, it was hard for the regime to perceive these ornithologists, entomologists, herpetologists, mammalogists, botanical ecologists, and biogeographers as sources of effective political speech. Marginality thus became a guarantor of the survival of scientific public opinion as a social identity.

That, however, created a dangerous contradiction for the movement, for its ethical norms demanded that it speak out when nature, and hence Science, was threatened. Too forceful a critique of policies to which the regime

was heavily committed, however, could create the impression that the nature protection movement was a nest of counterrevolutionary subversion. Accordingly, scientific public opinion had to walk a tightrope, negotiating between its ethical norms and its desire to survive.

Nature protection activists had made their peace with Bolshevik rule. They were Soviet patriots and had no pretensions to supreme power. Indeed, it can be argued that they had an investment in the perpetuation of an authoritarian, centralized state regime, for they sought to use the great power of the Leviathan-state to impose their "scientific" vision of environmental quality on the country as a whole. A democratically run government might not afford such possibilities. Yet, the actual Leviathan-state in which these scientists found themselves was controlled by boorish, vulgar bureaucrats who did not recognize the eminent rationality of the scientists' alternative vision of development. Because of their wish to participate in, and not destroy, the Leviathan-state, the scientists of the nature protection movement could only hope to persuade and enlighten these bureaucrats to invite them into the circles of power. Failing that, they could only wait for "better tsars."

This dilemma also expressed itself in the movement's perennial conflict over its lack of a "mass character." A multiply determined double bind, this question concentrated many of the conflicting pressures on the movement. When the regime turned its attention to the movement and its flagship society, VOOP, it invariably leveled the criticism that VOOP had failed to become a "mass society." By this, regime arbiters meant that the Society still had an elitist, corporativist spirit and had not yet become a reliable, Soviet-type society, that is, a transmission belt to mobilize large, organized segments of the population on behalf of the regime's objectives. That was precisely the kind of organization that VOOP's leaders sought to avoid allowing it to become.

But it was possible to construe a "mass-based voluntary society" differently. Such a society, if it were truly independent, could represent a real social force in support of the goals of nature protection. At times, a platonic desire of scientific public opinion to see itself as leading such a mass movement may be fleetingly perceived in the internal conversations of movement leaders. However, the reality of VOOP becoming a truly mass society under Soviet conditions was too frightening and risky for the scientific intelligentsia. An authentically mass society, if truly democratic, might throw off the tutelage of the scientific experts. Worse yet, a truly activist mass society would certainly elicit the harshest repression from a frightened Party-state, destroying scientific public opinion and all nature protection goals in the process. Consequently, the scientific intelligentsia could not permit VOOP to become a truly popular organization.

Nevertheless, the creative leaders of the movement were able to cobble

together a tolerable solution to their image problem. After World War II an aggressive effort was made to recruit teachers and schoolchildren as members. Additionally, and with somewhat greater reservations, the society began to enlist "juridical members," that is, whole ministries, factories, and other institutions that joined in the name of their workers and staffs. This, of course, made such employees' membership a formality—little more than a source of income from membership dues. However, by the early 1950s these measures boosted membership over the 100,000 mark. This solution was so inventive because it created the impression that the leaders of VOOP were building a "mass society" while ensuring that the new members—nonparticipating employees of "juridical members" and pliable schoolchildren—would not be in a position to challenge the dominance of scientific public opinion in the affairs of the Society. VOOP would only become a "mass voluntary society" in the Soviet sense after its takeover in 1955 by Communist Party bureaucrats, enforced by a decision of the Russian Republic leadership. Indeed, with twenty-nine million "members" by the 1980s, VOOP became the largest nature protection society on the planet, not to mention one of the largest nonstate businesses in the USSR.

Instrumental Shame, Protective Coloration, and Civic Honor

In January 1956 Aleksandr Formozov revealed to a large conference of Moscow conservationists his personal mortification at having to answer foreign colleagues' questions about the status of nature reserves and habitat protection in the USSR at an international gathering in Brazil the previous year. Similar statements by him and his colleagues at a variety of meetings also point to a general rhetorical strategy of using shame as an instrument to get the regime to adopt the scientists' nature protection policies.

In declaring that "we must think about all of the zapovedniki of the Soviet Union as we are all patriots of the Soviet Union," Formozov was not only proclaiming his authentic love of homeland. Patriotism was one thing, but being able to take pride in one's country was another, and that was at issue. Formozov and his scientist colleagues were telling the regime that they could not represent the USSR at international meetings with pride so long as the regime failed to restore the eliminated nature reserves and then move forward on that front. The high praise accorded to the new RSFSR Main Administration for Hunting and Zapovedniki (Glavokhota RSFSR) by Formozov ("the leadership of zapovedniki . . . is now in hands we can trust") and others reflected not merely their genuine pleasure and relief but also the hope that the Russian republican government would salvage the situation and remove

the blot of shame where the All-Union government was mired in inaction. To point out the patriotism of scientific public opinion and of the druzhinniki is neither criticism nor praise; it is merely noting one more piece of evidence against a romanticized view that sees these people as antiregime dissenters.

Similarly, it would be a mistake to view the frequent premeditated professions by VOOP of loyalty to "socialist construction" and other regime goals and values (what I call "protective coloration") as simply hypocritical, tactical moves aimed at enhancing its image. A number of key leaders of the movement, most prominently V. V. Stanchinskii and V. N. Makarov, were socialists going back to 1905, albeit Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, while a good many of their colleagues shared a common mistrust of a private property–based economy. Although dissenting from the regime's specific vision of economic development and environmental policy, scientific public opinion sought to work through the state, bypassing real democratic control over resource use. The student movements also sought to change things from above by occupying responsible positions in the machinery of power. Opposition to policies does not a subjective enemy of the state make. Protective coloration was a complex and negotiated response, containing elements of both cunning and sincerity.

Scientific Activists versus Civic Activists

Of the extant speeches in the available archival record of VOOP, a handful stand out for their passion and their unapologetic, unwavering tone of conviction. Curiously, those who uttered them were some of the most prominent nonscientist members of the VOOP inner circle: Susanna Nikolaevna Fridman, Aleksandr Petrovich Protopopov, Ivan Stepanovich Krivoshapov, and I. E. Lukashevich

Through the early 1920s, conservation discourse had been not only scientific but ethical and aesthetic as well. Ethical and aesthetic positions had been frequently voiced by scientist activists alongside scientific rationales for nature protection. By the late 1920s, this integrated mixture of motives, probably shared by the bulk of scientist activists, could no longer be expressed without penalty. Over the course of the decade ethical and aesthetic arguments lost their legitimacy and were derided as nonmaterialist and sentimental. Consequently, the public redefinition of nature protection as an exclusively "scientific" problem of ecology was an adaptive response by movement leaders, who recognized that the Bolsheviks might heed those speaking in science's name but might persecute those who advanced "moral" arguments for policy. For scientists, internalizing this claim of nature protection as a sci-

entific question additionally allowed them to fight for nature with the same sacred determination with which they would fight to defend Science. For fifteen years the ethical and aesthetic sides of the issue disappeared from view.

Accordingly, Susanna Fridman's remarks at VOOP's 1947 Congress were all the more startling. The longtime recording secretary of the Society and a nonscientist who considered herself one of the last remaining independent citizen activists in the country, Fridman dared to question the cornerstone of her scientist colleagues' authority. "Is nature protection," she asked, "or more correctly, the survival of wild nature and its capacity to blossom, compatible or incompatible with our quickly changing culture and civilization?" What was the opinion of science on that question? "Science has answered that it is compatible"; but, she wondered, what if science was wrong? In that case, she concluded, "our science is worthless, empty, and, as theory, holds no water. We know a great deal, but if we cannot [make the survival of wild nature compatible with culture], then that which we know wasn't worth knowing." This comment revealed the concealed tension between science and ethics within the nature protection cause and the parallel tension between scientific public opinion and those few citizen activists for whom "the public good" as they construed it outweighed the interests of science. Fridman, who emphasized that nature protection was a "momentous" question "not only of international but of planetary importance," was one of those few in VOOP who wanted to build the Society into a genuinely powerful independent mass society. "I must declare that in our Union we must engage in nature protection with pure and burning hearts and with passion," she emphasized, because, among the masses, "no one has any conception of the sweeping scope of this cause or of its crucial importance for the whole world. We must enter the international arena. Life itself urges us that way." As a final heresy she as much as stated that capitalist societies had "successfully tackled" a number of specific environmental problems still unsolved in the USSR.[17]

Fridman intriguingly suggested in 1957, one year before her death, that nature protection would become the universal creed that would unite humankind. "I have always believed," she wrote to her old friend Vera Varsonof'eva, "and now especially believe that the idea of nature protection will triumph, that precisely that idea will become the basis on which friendship between peoples will be built, which will give rise to common interests and to a universal common culture."[18] These were the thoughts of a civic-minded activist, not a scientist.

The difference between the VOOP scientists and the citizen activists is that scientific public opinion fought fiercely to defend its institutions—zapovedniki —and nature as "science," but the citizen activists defended nature as "nature," their personal civic dignity, and a larger vision of citizenship.

One could say that citizen activists provided the backbone that allowed their scientist colleagues in the movement to act more bravely. Tragically, as we see from the final letters of Susanna Fridman, the citizen activists were also the most socially isolated of all.[19]

The Students

Russia's two student nature protection movements—the druzhiny and the Kedrograd experiment—are treated in this study as historically and sociologically distinct from each other as well as from the citizen activists and scientific activists of the older movement. They seemed to resurrect the old spirit of the prerevolutionary studenchestvo . The druzhiny , especially the flagship brigade of the Biology Faculty of Moscow State University, were godparented by MOIP and scientific public opinion in the hope of reproducing another generation of activists in their own image. Although the students continued their teachers' commitment to zapovedniki , to an elitist self-image—brigades consciously limited their membership and long concentrated on the problem of poaching—and to the hope of using the monumental levers of power of the state to implement and enforce their environmental vision, they did not become yet another generation of scientific public opinion. Students sought to enter the natural resource bureaucracies rather than to stay in academe and wait vainly to be called to advise the political leadership. They sought to capture the levers of power themselves—as fishing, hunting, or water quality inspectors or nature reserve directors, administrators, and staff scientists.

The student activists of the 1960s and later raised action, not pursuit of science, to the apex of their hierarchy of values. Where scientific public opinion located its authority to speak out in scientists' reputations and erudition, the students viewed their moral authority more as a matter of course, arising out of their educational status. Historically, average citizens and Russia's various regimes (Stalin's excepted) were more inclined to indulge students' "excesses" and protests. For their part, students were impatient to engage in concrete forms of nature protection planning, practice, and enforcement, and all the more if these entailed a certain degree of adventure or even danger. This mood of action grew out of the hopes of the reform era of the 1950s and defiantly sustained itself during the long period of "stagnation" of the mid-1960s through mid-1980s. It also grew out of an entirely different education, received in the Soviet era, and out of changes in science itself; for a number of reasons it was no longer easy for young field biologists to acquire the scientific authority of the previous two generations.

During the crucial Khrushchëv years, the students revived a tradition of activism combined with the aura of moral authority that idealistic students customarily enjoyed in Russia. This produced efforts at practical resource

management and nature protection that brought the students into conflict with the Soviet bureaucracy. The stifling of Kedrograd, for example, vividly illuminated the gap between broadly shared social values, highlighted by the students' idealistic efforts, and the Soviet system. It therefore constituted a critical "object lesson," which catalyzed the far larger Russian nationalist/nativist movement of the 1970s and 1980s.

Stalinism as a System

Inspired by Marxian traditions, a trio of Hungarian ex-Marxists, Ferenc Fehér, Agnes Heller, and György Márkus, argue that in Soviet-type systems all economic investments, no matter how profitable or sensible they might seem or how likely to contribute to the general well-being, are judged by their likely effect on the stability of the system in the short term. They argue that this is tantamount to generating as big a flow of resources as possible into the hands of the central bureaucrats. Moreover,

the social usefulness of the end-product is graded according to its propensity to remain during its process of utilization under the control of the same apparatus or to fall out of it. . . . From the viewpoint of . . . a pure economic rationality, Eastern European societies are strangely and strikingly ineffective; they consistently make wasteful economic choices. This is, however, the consequence of their own objective criterion of social effectivity, of their own logic of development.[20]

Actually, there is a bit more here than a simple passion for aggrandizement. From a political standpoint, investments that seemed likely to create or enhance autonomous pockets of power irrespective of their economic and social "merit" appeared to the system as threats and were not approved. Conversely, those that manifestly propped up, reproduced, or augmented the power of the central bureaucratic apparatus were most heavily favored. Where decentralized investments seemed unavoidable, the system compensated with an increase in the capacity of the bureaucracy to monitor those potential nodes of autonomy, thus undercutting the economies achieved in the first place. This need for oversight fed the inexorable expansion of the apparat :

In a society in which all exercise of power has the character of a trustee/fiduciary relation and where systematically organized control from below is at the same time excluded in principle, a constant reduplication of the systems of supervision is an inherent and irresistible tendency. Processes of decentralization dictated by demands for greater efficiency are therefore constantly counterbalanced with attempts to impose new checks (and hence new systems of control), lest any unit . . . become so effective as to be able to follow its own set of objectives. It is in this vicious circle that the apparatus as a whole continues to grow, against all (sometimes drastic) attempts at its reduction.[21]

The bottom line is that "while the increasing social costs of bureaucracy may well be considered as a specific form of exploitation inherent to this society, the numerical expansion of the whole managing-directing apparatus, which is its main cause, certainly is not in the material interests either of individual bureaucrats or of their collectivity—in fact it only enhances the competition between them. And this tendency actually prevails against the articulated will of the apparatus."[22]

Ianitskii adds, "For the System, which to serve its own interests had created an economy of extravagance and shortages, environmentally safe technology was an empty phrase, and resource-saving was actually a threat to its wellbeing."[23] Consequently, the commitment of all regimes from Stalin's through Chernenko's to colossal "projects of the century" becomes eminently explicable despite those projects' long-term potential to undermine the system's viability financially and environmentally; each was perceived by the regime as one of the few options for politically safe large-scale economic growth, seen as essential to the perpetuation of the system. It is likely that these projects—Stalin's "Plan for the Great Transformation of Nature," Khrushchëv's Virgin Lands campaign and opening of Siberia with the Bratsk-Angara Dam, and Brezhnev's River Diversion Project and Baikal-Amur Mainline Railroad—also were thought to contribute to the system's stability in another way, in the arena of popular legitimacy. By each promising to represent one last "great leap forward" to Communism, the various "projects of the century" propagandistically endeavored to overcome the people's ever-increasing suspicion that the regime was actually a parasitic dead-end; each Soviet ruler had a "signature" program to legitimize his claim on leadership.

The opposition by the environmental movement in Russia to these big projects and to Soviet economic development generally from the early 1930s to the 1990s could be considered a continuous record of political opposition to the regime, attacking it at its very political-economic foundations. However, such a conclusion would have to assume some understanding on the part of nature protection activists of the connection between "the great transformation of nature" and the patterns by which the regime continually reproduced itself. The evidence does not currently support such a conscious realization. For activists, what was objectionable were the visible consequences of these patterns of economic development—for "nature," for society, and for their own social identity.

The Russian nationalist-oriented activists associated with opposition to the river diversion project seem to have developed a more conscious sense of the subversive nature of their campaign. Nicolai Petro writes that the river diversion project led critics to examine some of the structural attributes of the system, and concludes: "This criticism of the bureaucracy extends far beyond Minvodkhoz to all those who will fully confuse their own narrow-

minded interests with the long-term national interest. Careerism is thus disguised as social need."[24] In fact, he continues,

It is scarcely too much to say then that many of the critics of the diversion projects, both writers and scientists, espouse an alternative worldview to the one currently inculcated by the present political system. . . . The essential components of this alternative worldview are that science is not the solution to human problems because it does not address the need for spiritual and moral values, and that proper morality should be based on patriotism as manifested in an individual's personal responsibility for his country, its history, and its culture.[25]

Still, no branch of the environmental movement was able to articulate a critique of the system rooted in political economy or to offer a clear picture of an alternative way of organizing economic life. True, there were times when the older scientists' movement and students subjected individual government officials to interrogation and even humiliation. One could even call the conferences of 1954, 1957, and 1968 (where activists demanded the resignation of USSR agriculture minister Matskevich) carnivalesque inversions of the Shakhty, Industrial Party, and other show trials of the late 1920s and early 1930s directed against the scientific and technical intelligentsia. Independent civic associations seizing such initiative would seem to constitute a prima facie case of subversion from the Party's standpoint.

Why then did the regime tolerate these implicitly subversive movements when it easily could have obliterated them just as it had so many others? Could it not see that nature protection discourse and the zapovedniki represented a last holdout of an alternative cultural and political resistance? Did the regime not understand the implications of the activities of VOOP, MOIP, the kruzhki (circles), and the druzhiny , that they challenged or undermined core values and policies of the leadership? Why did the activists not become object lessons regarding the transgression of the rules of permitted Soviet speech?

A conclusive, let alone unitary, answer to this problem probably will never emerge from available archival sources; we can only speculate. However, a number of explanations should be considered. First, the regime did not expect political speech from field biologists and geographers, whom it considered arcane eccentrics and whose economic relevance it barely acknowledged. They were at once too unimportant to worry about and too silly and strange to be perceived as serious political threats.

Second, an oppositional role was not the activists' default mode. For these individuals, nature protection was an absolute injunction or sacred duty. However, the rationality and the protective role of suppressing the political and social implications of what they were doing must be appreciated. Were their everyday agitation on behalf of nature less naively passionate and more

self-conscious, their presentation of self in the public arena would have been more characterized by "bad faith." Arguably, they would have then been more vulnerable to being "unmasked" as dissidents in Soviet society. As naive "nature lovers" they presented a convincing image of harmless and somewhat ridiculous cranks and oddballs —chudaki. The fact that the leadership of the movement consisted of world-class scientists—botanists, zoologists, geographers—made their nature protection appear from the regime's perspective to be an eccentric and low-cost hobby. Nature protection only appeared on the regime's radar screen when those in power decided that they had other uses for the resources and lands (zapovedniki ) used by the movement for its "hobby." At that point the activists' resistance potentially acquired a new, subversive cast . . . because someone was finally paying attention!

Third, the various movements were authentically patriotic, for the most part, and had no intention of overthrowing the system. Even when Malinovskii and Bochkarëv were publicly humiliated by activists, activists' criticisms were leveled at these men as individuals or even "bureaucratic types," not as representatives of a rotten system.

Fourth, the nature protection movement was assisted in its quest for survival and influence by high–and middle-level patronage and protection. Activists looked to institutional patrons and protectors of all kinds to give or secure them their little bit of social space, and so they were imbricated to some extent in the system. Without allies they never could have preserved and maintained their "archipelago of freedom." A series of premiers of the RSFSR and local, oblast' -level politicians proved to be true friends and protectors of both the reserves and the nature protection movement. Academy of Sciences president Nesmeianov had enough power to provide wiggle room for this politically aberrant group and let the Academy serve as a Noah's ark for displaced ecologists after 1951. Gosplan leaders Saburov and Zotov respectively tried to mitigate Stalin's and Khrushchëv's depredations against the zapovedniki. Lesser leaders had the power to give space as well. The druzhiny could not have existed long without the patronage of the Komsomol (the Young Communist League) and of local branches of VOOP.

The motives of the movement's patrons were not identical. Nesmeianov, it appears, was personally committed to the cause of nature protection. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the leaders of the Komsomol saw patronage of the druzhiny as a means of burnishing the image of the Komsomol as "liberal" while keeping tabs on the potentially disruptive druzhinniki. And although many of the RSFSR and oblast' politicians did not act out of ideologically conscious "liberal" sentiments, they did seek to protect "their own" scientists, territories, and jurisdictional portfolios from the grasp of the center. After Stalin's death the republican governments, often with the support of local authorities, took the lead in reconstituting the disbanded nature re-

serves. Did that patronage morally obligate the nature protection movement to restrain itself so as not to endanger their patrons? Unwritten understandings about the permissible limits of public speech doubtless played a role in framing policy dissent. This is not a story about "black hats" versus "white hats." All of these actors are located somewhere on the same spectrum. Even Aleksandr Vasil'evich Malinovskii emerges from this study not as an irredeemable "evil genius" but as a Soviet bureaucrat whose vision of a "souped up" nature was at once utopian and utterly pragmatic.

Although it might appear that my research has discovered currently sought-after seeds of "civil society," the story is not nearly that simple. Perhaps it is even a good deal more ironic than it seems, for the very conditions—tsarist and Soviet—that gave rise to the social identities explored here also made them largely self-limiting. They testify to the durability of corporativist or guildlike social identities in Russia. Such mutually uncomprehending guildlike social groups could achieve solidarity only during rare moments, such as 1905 and March 1917, but could not sustain it, allowing a Bolshevik autocracy to supplant the fallen tsarist one. The independent groups portrayed in this study do not seem to have transcended this pattern.

This study trains its sights on what James Scott has called "hidden transcripts,"[26] drawn from the worlds of documents, statements, and social practice, which testify to the existence of Soviet social sites where alternative values and visions of the world were affirmed, shared, and perpetuated. This it does not merely to find inspiring examples of resistance under dauntingly difficult circumstances but to shed light on the nature and evolution of the social identities of scientist-activists and other activists and the ways in which they experienced their world and accommodated to it. Such portraits must necessarily also point out the ways in which these individuals were integrated into their larger society and system; although near the margins of the officially sanctioned social order in some respects, they could not fully escape dependency on the system. Their activism never countenanced a frontal challenge to the supreme political authority of the Party-state. Nor were they equipped to join with other social groups to defend social interests alien to their own, owing to their insular, caste-based psychologies. In a word, they were not dissidents in the way we now understand that term and were not fully formed nodes of civil society. But that in no way diminishes their achievement of establishing autonomous social identities for themselves on the basis of their own internal compasses against the pressures and directives of a jealously authoritarian system.

This book is organized chronologically, although the story is not entirely genealogical. After a discussion in chapter 1 of the various social identities

adopted by members of the Soviet nature protection movement and a brief synopsis of the movement's background through the early 1930s, chapters 2 through 8 trace the history of the field naturalist–dominated nature protection movement during the remaining and most repressive portion of Stalin's rule. That section culminates with an extended exploration of the circumstances surrounding Stalin's decision to "liquidate" the great bulk of the nature preserves and the concurrent investigations into the All-Russian Society for the Protection of Nature, which only narrowly escaped being shut down itself.

Chapters 9 through 13 cover the decade following the death of Stalin in 1953. They focus on the remarkable and almost single-minded efforts of this scientists' movement to pressure the authorities to restore the eliminated zapovedniki , efforts that included the convening of mass scientific conferences involving hundreds of participants to protest the closings. These chapters also show the adaptive flexibility of the movement, which was able to relocate its institutional site to the Moscow Society of Naturalists and to the Moscow branch of the Geographical Society of the USSR when in 1955 the RSFSR authorities quashed the independence of the All-Russian Society for the Protection of Nature.

Chapters 14 through 19 cover the period from the emergence of the university student movements of the late 1950s to early 1960s through perestroika , although the latter deserves more space than I have allotted here. In this last portion of the book focus on the old field naturalists' nature protection yields to a portrayal of new social actors: the student druzhina and "Kedrograd" groups, the emergence of a Russian cultural-patriotic nature protection movement, and the larger coalition of all of these groups in opposition to the industrial pollution of Lake Baikal and the project to divert northward-flowing Siberian and European rivers to the drier south. The book ends by noting the emergence of mass protests by ordinary Soviet citizens. The Conclusion distills new insights into Soviet history and environmental history from the story of the nature protection movements told here.

This study's focus is elusive: charting the role of organized participation in nature protection advocacy as a unique arena for affirming and perpetuating self-generated social identities, ipso facto a subversive undertaking in the eyes of the Stalinist state. Complicating this task is that nature protection provided the symbols and rhetoric around which more than one distinct, autonomous subculture was organized in Russia. Consequently, this is a study of how "nature protection" as an aesthetic, moral, and scientific concern and as a source of symbols and rhetoric was used creatively by Soviet people to forge or affirm various independent, unofficial, but defining social identities for themselves.

One who noticed this role for environmental activism is Oleg Ianitskii, who called attention to ecological protest as the formal banner under which any kind of political expression originally marched at the dawn of perestroika :

The struggle against the dictatorship of the Center, for national autonomy and for the preservation of national culture, for civil rights and freedom, against the arbitrary rule of the local bureaucracy, for self-government and the right to participate in the taking of decisions—all of these social actions marched either partially or wholly under ecological slogans. One way or another, ecological protest during the period 1987–1989 became the USSR's first legal form of democratic protest and of solidarity among the citizenry as a whole . . . [although] the motivations and goals of this "ecological uprising" were quite divergent for different participants in this struggle.[27]

Was it purely accidental that emerging Soviet citizens first chose to march "under ecological slogans"? Certainly, the April 1986 Chernobyl disaster played a large role, graphically demonstrating the consequences of the system's wanton and decades-old disregard for the health and environmental safety of the population, and moving people to notice and speak out about environmental threats in their own localities.[28] But also Soviet people knew that historically, unlike political, religious, ethnonationalist, labor, or even cultural dissidents, environmental protesters were not greeted by billy clubs, water cannons, imprisonment, deportation, or exile. A host of compelling problems angered Soviet people in the early days of glasnost'. Any one of those could have served as the focal point of their initial public protests. People almost universally chose environmental issues, however, because they were aware of the low risk historically associated with speaking out in that area. This study reveals that environmental protest and activism served as a surrogate or even a vehicle for political speech continuously throughout the Soviet period. In Ianitskii's words, "Nothing arises out of a vacuum. Perestroika and reform measures do not represent isolated actions but an extended process, which has its prehistory."[29] That prehistory is the central subject of this book.

Chapter One—

Environmental Activism and Social Identity

Some who have reflected on the prehistory of Russian environmentalism, such as the geologist Pavel Vasil'evich Florenskii, a former member of KIuBZ (the Young Biologists' Circle of the Moscow Zoo), believe that the environmentalist ethos draws its source far back in time, from the traditions of brotherhood that flourished in Pushkin's day at the Tsarskoe Selo Lycée, which then were revived in the traditions of the St. Petersburg University studenchestvo (radical student subculture).[1] These traditions somehow survived in the kruzhki (circles) that the Soviet-era nature protection movement created to ensure the perpetuation of its values and social identity:

In the children's circle a collective was forged of like-thinking individuals with their democratic structures, independent self-governance, continuity over the generations, here were molded principles of morality, traditions of friendship, an awareness of our unity with nature and of the need for an eternal dialog with it. The free Young Naturalist life was a life-filled alternative to the dry and bureaucratized school and the decayed Pioneer and Komsomol organizations. Having been members ourselves in our childhood and adolescence of this noisy youthful community, we continue to feel to this very day that back then we swore our loyalty in friendship and our loyalty to nature. KIuBZ and its spin-off, the VOOP circle, were the nurseries where the future leaders of the nature protection organizations were lovingly cultivated and where the principles were honed that later would provide the basis for the charters of environmental organizations. . . . [S]ince [the 1950s] the nature protection movement has irrepressibly grown, realizing an "ecological niche" in all age and social groups. Its schools were the student druzhiny for nature protection—as well as "Kedrograd" in the Altai. Those were the milieux where the country's future "green" movement's leaders were molded.[2]

We cannot say for sure whether the continuity of the ethos of the tsarist-era studenchestvo was unbroken before it reemerged within the university brigades for nature protection in the 1960s. However, Florenskii and Shutova

are right to point to the linkages between a decades-old nature protection movement, that movement's youth organizations (especially from the 1940s onward), and the university student nature protection brigades (druzhiny ) of the 1960s through 1980s to which the older movement gave rise.

Tempting as it may be, however, it would be an error to conflate the distinctive groups of Russian activists into a unified "environmental movement." The earlier nature protection movement of the field naturalists and activists, the later movements of university students and of engineering and technical students, the Russian national-patriotic movement for the protection of nature, and the mass protests of the late 1980s all must be distinguished from each other sociologically despite the links between them. Although all these currents enlisted the rhetoric of nature protection, they drew inspiration from sometimes quite distinct cultural, professional, and ideological traditions. For example, the druzhiny echoed the hoary traditions of the Russian studenchestvo , whereas the "scientific public opinion" of their professor-mentors was rooted in the prerevolutionary ideology of the old academic intelligentsia. Those divergences reflected underlying social differences among the members of these various environmental activist movements: levels and kinds of professional training, professional or career status, social origin, and generational cohort. Admittedly, the distinctions made here are overschematized; nevertheless, our insight is better served in this case by splitting than by lumping.[3]

If environmental activism served as an unauthorized form of public speech, what were the "speakers" trying to say? They were not all saying the same thing. Only by understanding what anthropologist Walter Goldschmidt has called the various "human careers" of members of these distinct groups may we begin to grasp the part played by environmental activism in their struggles for self-definition and self-affirmation under evolving Soviet conditions.[4]

Scientific Public Opinion as a Social Category

To understand one of the most important social meanings of environmental activism in the Soviet period, it is first of all necessary to appreciate its connection to a Russian ideology of science and learning that emerged during the tumultuous years of the late 1850s and early 1860s.[5] In those years a "mystique of nauka " (science, learning), in James McClelland's phrase, gripped an entire generation of Russian educated youth. Whereas the tsar and the political system proved limited and flawed, science held out the promise of nothing less than the secular redemption of the world. Its adepts were characterized by "an enthusiasm that elevates and enthralls a person, a conviction that he is doing something that is capable of absorbing all of his intellectual inclinations and moral energies—something which . . . enters as

a necessary constituent part of the much broader general movement that will guarantee the eventual elevation of the intellectual and material well-being of the public as a whole."[6] Russian scientists and academics retained this faith in the redemptive power of science up to and through the Bolshevik Revolution.

One corollary of this ideology was that a life in scholarship conferred moral superiority. A scholar not only became a knight in the army of enlightenment but also acquired through learning a superior moral vision. As a rule, liberal politics—including opposition to tsarism, support for some kind of representative democracy, belief in intellectual freedom, and commitment to civil and human rights—formed part of this vision of an enlightened future. Among professors, this "mystique of science" was colored by a shared "caste" or "corporate" sensibility.[7] They embraced a social identity that McClelland has called an "academic intelligentsia," which,

while subscribing to the general outlook of the larger liberal intelligentsia as a whole . . . developed an additional and distinctive viewpoint of their own, which stressed the vital importance of university autonomy and the role of nauka in Russia's future social and cultural development. The majority of Russia's professors, in short, were more than just scholars and scientists. They formed a closely knit and articulate sociocultural group which sought to embody in its academic activities a moral commitment to progress and reform.[8]

A further component of this ideology, at least among many academics, was a high regard for basic or fundamental research, what the Russians called "pure science" (chistaia nauka ). If science and learning were a secular religion then pure science was its most sacred precinct, undefiled by outside political, commercial, or social pressures. Pure science embodied the principle that true academics answered only to the ethical injunctions of their priestly calling.

By the first decade of the twentieth century, nauka became a more contested issue. Certainly not all educated Russians endorsed the ideology described above. Progressive but loyal tsarist bureaucrats, seeking to modernize the country, had an obvious stake in denying that the march of knowledge would inevitably lead to the downfall of the autocratic order. On the one hand, they lobbied for greater regime support for academic institutions; on the other, they tried to convince academics of the need to dissociate learning from antiregime politics.

At the other end of the spectrum, radicals, especially students, demanded that academics actively subordinate learning and science to the struggle against autocracy. In its later incarnation in the postrevolutionary period, this view denied the possibility of science and learning independent of socioeconomic and ideological interests and consequently came to challenge the notion of an autonomous, value-free realm of "pure science."[9]